INTRODUCTION

The numerous gods of central Mexico were identified by a principal name and several secondary names, as well as by the ornaments encasing their anthropomorphic figure. These attributes, which contained the visual part of their identity, were represented two-dimensionally in the pictographic manuscripts, carved stone bas-reliefs, moulded, shaped or engraved ceramic objects, mural paintings, and three-dimensionally in the statuary and array of the men and women who personified the deities during the rituals. How can we decipher the information that they contained? This question was raised from the time of the first studies of the divinatory manuscripts from central Mexico (particularly those of the Borgia Group) by Eduard Seler and was then developed by numerous scholars with regard to the pictographic manuscripts in general. It can be considered that the gods are visually identifiable by their facial paint, body coloring, body suit, headdress, and jewelry (e.g., nose ornaments, ear ornaments, and pectorals; Boone Reference Boone2007:39–44). Generally speaking, however, a single ornament does not suffice to identify a god; it is necessary to recur to the entirety of their traits, for example, the combination of facial paint, headdress and shell pendants that compose the images of Quetzalcoatl (Boone Reference Boone2007:43) and others features that compose the image of Huitzilopochtli (Boone Reference Boone1989:5–9). The situation becomes complicated when it is observed that several gods share certain attributes, a characteristic that has led scholars to group the gods by traits of affinity (Nicholson Reference Nicholson and Folge1963, Reference Nicholson and Wauchope1971; Spranz Reference Spranz1973; Tena Reference Tena2009). A discussion arose from this issue concerning which traits were associated with the identity of the god and which were secondary. Several proposals were made including establishing, for example, the existence of “diagnostic insignia” assigned to each deity (Nicholson Reference Nicholson and Wauchope1971:408), the distinction between “determinant forms” and “isolated forms” (Spranz Reference Spranz1973:27–28), or between “distinctive” (rasgos distintivos) and “optional” traits (rasgos discrecionales; Mikulska Dabrowska Reference Mikulska Dabrowska2015:80). Scholars were thus confronted with real difficulties in establishing the principles of composition of divine images in codices and rituals.

With good reason, researchers have recently given thought to the divine nature of the deities from the conception of god (teotl) and embodied deities (teixiptla; Bassett Reference Bassett2015) and their performance during ceremonies and feasts (DiCesare Reference DiCesare2009). Notwithstanding, I contend that the line of inquiry opened by Seler and Nicholson, consisting of taking the visible divine attributes as the starting point to attempt to understand the conceptual fashion of constructing the idea of a god, has not been exhausted. As Boone (Reference Boone1989:9) wrote, it is important to consider “the physical objects or visual elements (costume parts, colors, implements) that embody or contain within them particular qualities or properties,” so that “Huitzilopochtli's nature is defined by the list of his attributes.” Considering that the nature of each of the gods can be inferred from his or her attributes, my method consists of isolating the ornaments composing their images and recomposing them by function of their meaning, as I will show below.

To achieve this goal, I have chosen Chalchiuhtlicue, the Aztec goddess who represented and incarnated water: Chalchiuhtli icue, in ipan mixehua atl (Florentine Codex [Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 4, p. 99]), from the verb ipan mixehua, to “represent” or “personify,” as used in a group of synonyms together with (te)ixiptlati, (te)ixiptlatia, “to become the impersonator or ixiptla of a being or a thing” (see, for example, Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 7, p. 27). Chalchiuhtlicue covered the entire range of the natural manifestations of water. In fact, the Nahuatl term designating this element (a-tl) allows us to form all the words alluding to the places where it was present: springs (a-meyalli, a-papatztlan), fountains (a-patzquitl), cisterns (a-tlacomolli, a-yolhuaztli), rivers (a-toyatl), lakes (a-manalli, a-xoxohuilli), mist (a-yahuitl), and so on. Most often, the names of sources and rivers were composed from the word atl (e.g., Tozpal-atl, Nex-atl, Coa-atl, and Tlil-atl).

Chalchiuhtlicue was also endowed with social functions and presided over all the numerous activities in which water was involved. For this reason Durán (Reference Durán1995:vol. II, ch. 19, p. 175) could write: “[i]n it they were born, and with it they lived, and with it they washed away their sins, and with it they died” ([e]n ella nacían, y con ella vivian y con ella lavaban sus pecados y con ella morian), a phrase that summarizes the areas of competence of the deity. The assertion “in it they were born” designates the role that water played in the steam bath (temascal) rituals that took place before and after childbirth. The phase “with it they lived” refers to its function in irrigating and fertilizing the land in which the goddess was the elder sister of the pluvial deities known as the tlaloqueh (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 1, pp. 20–22). Allusion was also made to her role in drink and food, since Chalchiuhtilcue was one of the nurturers of the group that also included Chicomecoatl (corn) and Huixtocihuatl (salt; Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 1, p. 22). The assertion, “with her they washed away their sins,” synthesizes the purification function of the goddess, one of her most important ritual attributions, of which repeated mentions are found throughout the Florentine Codex. Chalchiuhtlicue thus presided over birth rituals, the bathing of sacrificial victims and ceremonial actors, judiciary purification, royal investiture and in the recycling of ritual waste. Finally, “with her, they died,” because the goddess presided over the funerary ritual washing of the body. To this must be added her role in punishment by flood (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 6, p. 258) and drowning (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 1, p. 21), as well as in divination (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 1, p. 70). Nicholson (Reference Nicholson and Folge1963, Reference Nicholson, Klor de Alva, Nicholson and Quiñones Keber1988) and Olivier (Reference Olivier and Carrasco2001) have dedicated works to the iconographic representations of Chalchiuhtlicue and López Luján and Fauvet-Berthelot (Reference López Luján and Fauvet-Berthelot2005:Statues 10–17) have studied several three-dimensional representations of the goddess.

What were the principles involved in constituting the image of Chalchiuhtlicue? To respond to this question, I have selected representations of the goddess in several codices from central Mexico. I have included in my selection prehispanic divinatory manuscripts (Codex Borgia [Seler Reference Seler1988a:ff. 11, 14, 17, 20, 65; commented by Seler Reference Seler1988b:vol. I, p. 80], Codex Fejerváry-Mayer [Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1994a:ff. 3–4, 7–8, 9–10, 29–30, 33–34], and Codex Cospi [Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Van der Loo1994b:ff. 1–8]) whose provenance, according to recent studies (Boone Reference Boone2007:229), was probably the region including the cities of Tlaxcala and Cholula in central Mexico, the Mixteca region, and the southern part of Veracruz. We do not know exactly what languages were spoken by their scribes (Nahuatl, Popoloca, Chocho, Mazatec, Mixtec, Cuicatec, or Otomi), except in the case of the Codex Cospi, which was in Nahuatl (Boone Reference Boone2007:229); currently, there is strong reason to believe that the Codex Borgia was painted by Nahuatl-speaking scribes (Mikulska Dabrowska, personal communication 2017). The remaining manuscripts considered were probably made following the Spanish Conquest in the Aztec tradition, in the Nahuatl language: Codex Borbonicus (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:ff. 5, 35), Codex Magliabecchiano (Anders Reference Anders1970:f. 75r), Codex Tudela (Tudela de la Orden Reference Tudela de la Orden1980:f. 13r), Codex Vaticano A (Anders and Jansen Reference Anders and Jansen1996:f. 14v), Codex Telleriano-remensis (Quiñones Keber Reference Quiñones Keber1995:f. 8v), as well as the Primeros Memoriales (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1993:f. 263v) and the Florentine Codex (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1979:bk.I, ch. 9, f. 5). Finally, I have included some examples of statuary (statues of Chalchiuhtlicue, Museo Nacional de Antropología, object number 10-82215, in Stresser-Péan Reference Stresser-Péan2011:55; British Museum America, Statue 373).

The method I use to analyze Chalchiuhtlicue's array consists of breaking down the signs scattered over her body (facial paint, nose ornament, headdress, dorsal ornaments, necklace, shift, skirt, sandals, and bracelets), and then grouping them according to their meaning. This allowed me to develop a table (Table 1) listing water, rain, jade, gold, and reptiles as what I call “semantic groups.” Each of these groups brings together a certain number of conventional signs that I call “designs,” whose code consists of a shape (e.g., spirals or stripes) and a chromatic composition (e.g., blue and black).

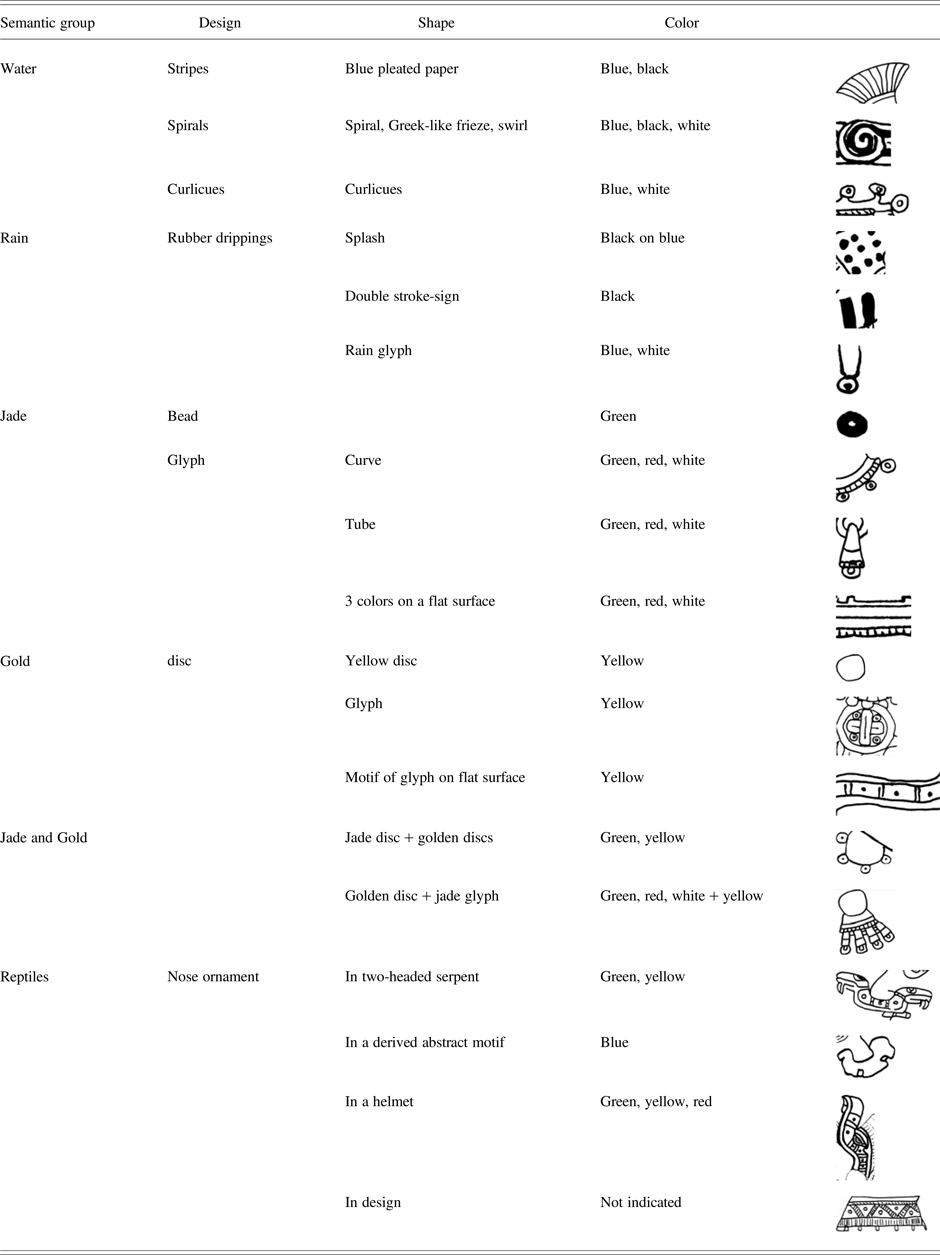

Table 1. The conventional signs to designate water, rain, jade, gold and reptiles making up Chalchiuhtlicue's attributes.

It should be noted that López Austin (Reference López Austin1985:257–258) had previously broken down the elements of a Mexica sculpture and regrouped them in four “fields of symbolic relations” (fire, water, death/earth/water, and earth) and a set of unidentified traits. The foundation of my method consists of envisaging each design as transmitting a particular meaning, so the essential moment consists of attributing a meaning to each design. To do so, I recurr in large part to the explanations furnished by Sahagún's informants in Nahuatl in the Primeros Memoriales (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1979) and Florentine Codex (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982).

Certain attributes have several meanings depending on the context. This is the case of the yauhtli flowers (Tagetes lucida), associated with the vegetation deities as well as the fire god (López Luján Reference López Luján2006:vol. 1, p. 216; Taube Reference Taube, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000a:278–280), the meaning of which will be discussed below. What is more, the attributes making up the figure of Chalchiuhtlicue do not necessarily pertain exclusively to her, since, as stated above, it is the whole set of motives that characterize the goddess. Consequently, she can share, for example, the sign standing for rain (i.e., rain water) with Tlaloc and other fertility gods, although she incarnates ground water. There is no contradiction here. Quite the contrary, ground water was thus connected to rain water with which it forms a whole, and Chalchiuhtlicue was associated with Tlaloc in temples as well as in ritual practices. With these precisions in mind, I will now proceed to present a detailed comment of the table of analysis of the attributes of Chalchiuhtlicue.

THE DEPICTION OF A GODDESS COMPOSED OF CONVENTIONAL SIGNS

The conventional designs or signs consist of the combination of shapes and chromatic composition, the whole of which form a sort of code. What is the nature of this code? It is generally accepted Mesoamerican visual communication systems were characterized by an association between the graphic signs that encode syllabs or words and the images whose function is iconic.

In the first case, the graphic sign is known as a glottogram, glottograph, or glyph because it encodes a sound or a meaning emitted in a particular language. Beyond their variety, glottographic procedures use signs whose purpose is to be read and pronounced, distinguishing them from images whose object is to transmit non-verbalized information. All Mesoamerican writing systems (Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan, Isthmian, Zapotec, and Mexica-Aztec) recurred to these two types of signs (Stuart Reference Stuart2015:2; Taube Reference Taube2000b:2–4), and debates among scholars have centered around what proportion of one or the other type was used. While Mayan epigraphers tend to emphasize glottographic procedures (Lacadena Reference Lacadena2008a; Stuart Reference Stuart2015:2), scholars specializing in religious manuscripts with divinatory content from central Mexico frequently use terms such as figure, image, and visual art (Boone Reference Boone2000, Reference Boone and Houston2004, Reference Boone, Boone and Urton2011), to cite only a few of the authors engaged in this discussion.

Specialists in the visual communication system proper to central Mexico maintain that pictures predominate in religious manuscripts, whereas glottograms are privileged to denote the names of persons, titles, and place names (e.g., Boone Reference Boone, Boone and Urton2011:385; Mikulska Dabrowska Reference Mikulska Dabrowska2015:210–211; Nicholson Reference Nicholson and Benson1973:2). This is precisely what I assumed when I began the present research on the attire of Chalchiuhtlicue. I soon discovered, however, that most of the designs used to compose her divine representation were also present in Nahuatl toponyms, i.e., in glyphs making up scripts. I will elaborate on this point below, but since the terms used in the field vary from author to author, I will state briefly my definition of glyph: “a sign in a script composed largely of pictorial elements” (Whittaker Reference Whittaker2009:54).

There is a difference between two types of signs: one class has a semantic value (which I will call morphograms); the other class has a phonetic value (which I will call phonograms). The morphogram is “a semantic sign representing a discrete unit of meaning (morpheme) or a compound of such” (Whittaker Reference Whittaker2009:54, Reference Whittaker and Colm Hogan2011:936). In Nahuatl, morphograms are lexical, so they represent words (nouns and adjectives) and are communly called logograms or word signs. Here, I prefer to use the term “morphogram.” Since their value is semantic, morphograms can be read and understood in different languages. Thus, a glyph representing water can be enounced as atl in Nahuatl, but also read in other languages such as Mixtec and Otomi in the same way as we pronounce water in English or agua in Spanish.

The phonogram is “a phonetic sign representing a linguistic sound (phone) or a sequence of sounds” (Whittaker Reference Whittaker2009:54). It is a wordplay on homophony, making use of rebuses, and allows us to read a word that is semantically distant but phonetically close. Phonograms are not unusual in the toponyms transcribed in the Codex Mendoza: thus, -tlan (“among,” as in the toponym “Among Women,” Cihuatlan) is represented by the phonogram tlan (“tooth”). The phonogram is thus linked to a particular language, in this case Nahuatl (Gaillemin Reference Gaillemin2013:248–253).

There are many methods currently in use to transcribe morphograms (Whittaker Reference Whittaker2009:57–58). One can use either phonetic characters or standardized classic Nahuatl spelling. I have chosen the latter for this article, following Launey's (Reference Launey1986) standardized spelling with the exception of the phoneme known as the saltillo (glottal stop), which will be indicated by -h. In addition, there is a tendency nowadays to distinguish morphograms from phonograms by representing the former in small caps and the latter in small letters: for instance, the morphogram A[TL] “water,” and the phonogram tlan, “among,” “tooth,” in illustration of the above examples. Finally, it should be noted that I will write the nominal suffix in brackets which, in Nahuatl, is removed when the noun is used in composition: for example, in A[TL], the suffix [TL] can be left out, leaving only the noun A.

We will now see that the designs covering the body of the Goddess of Water are very frequently found as morphograms or phonograms in the toponymic glyphs of the Codex Mendoza, a Colonial manuscript in which the pictographs are accompanied by glosses in Nahuatl and in Spanish.

Water

As stated above, Chalchiuhtlicue incarnated and represented water. It is therefore not surprising that her image contained different attributes referring to this natural element.

The Toponymic Glyphs for Water

In the Codex Mendoza, there are numerous toponyms made up of several glyphs, one of which encodes the word A[TL] (water), and is thus a morphogram according to the terminology I have adopted. Our research shows that the complete glyph for water is composed of three elements: black stripes on blue-green stripes, a spiral, and a characteristic edging designed as a series of wavelets carrying at their tips alternating droplets of water and shells. It should be noted that only in the Colonial Aztec manuscripts from central Mexico do the “tips” of these edgings have these drops and shells. In contrast, in the Codex Borgia they are represented as simple protuberances (sometimes ending in small round circles standing for gold, jade disks, or excrement and acting as qualifiers and providing greater precision to the meaning).

The complete glyph for water is found, for example, in the Codex Mendoza, in the graphic representation of the Anenecuilco toponym: a[tl]-nenecuilli, “Water of the Inga jinicuil Tree,” following the botanical identification proposed by Karttunen (Reference Karttunen1983:167). The toponym is represented by means of the glyph for water with its three components—stripes, spiral and shell/water drop edgings (encoding a[tl]), to which the shape of a tree is applied, encoding the Inga jinicuil tree; Figure 1a).

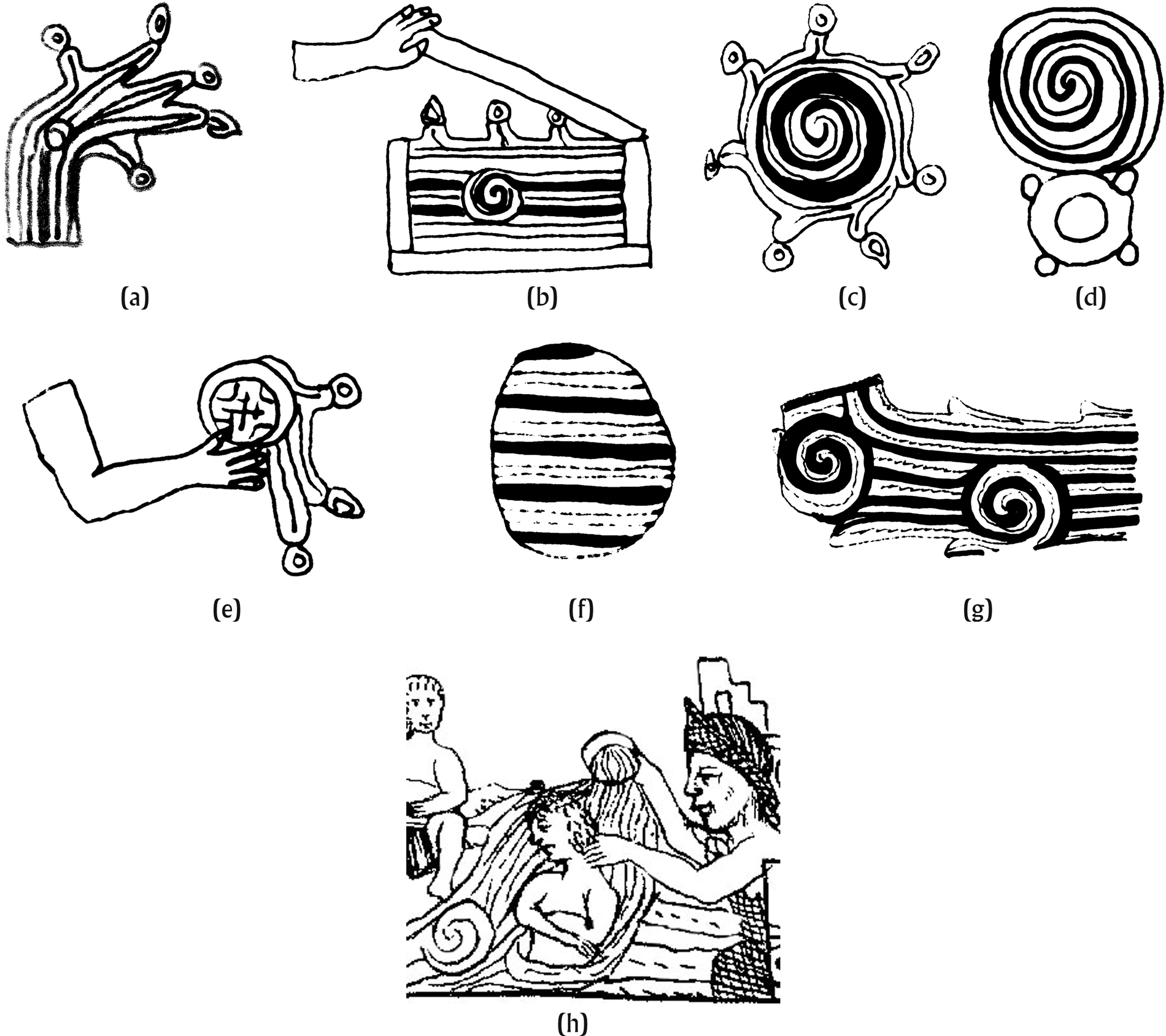

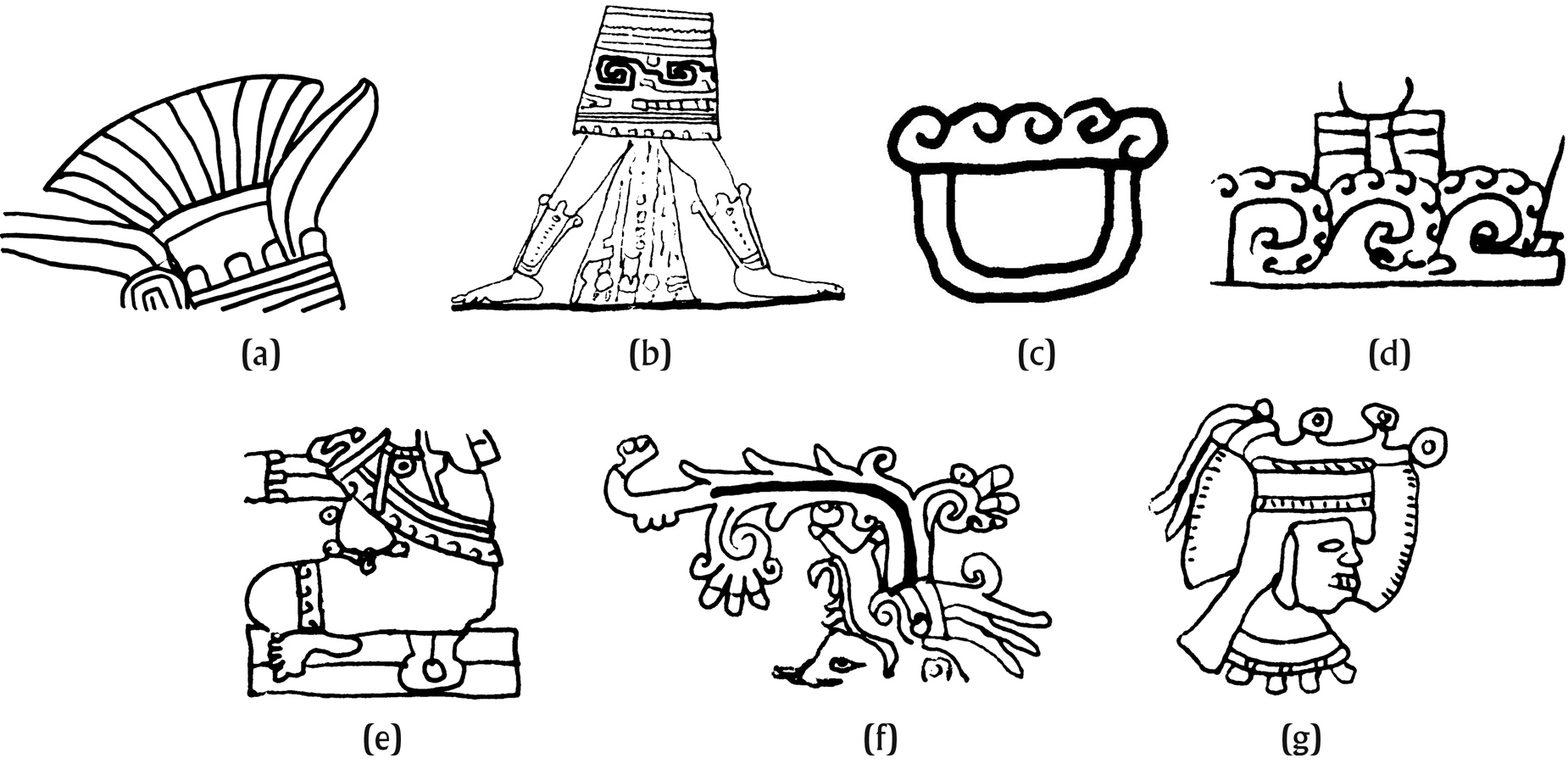

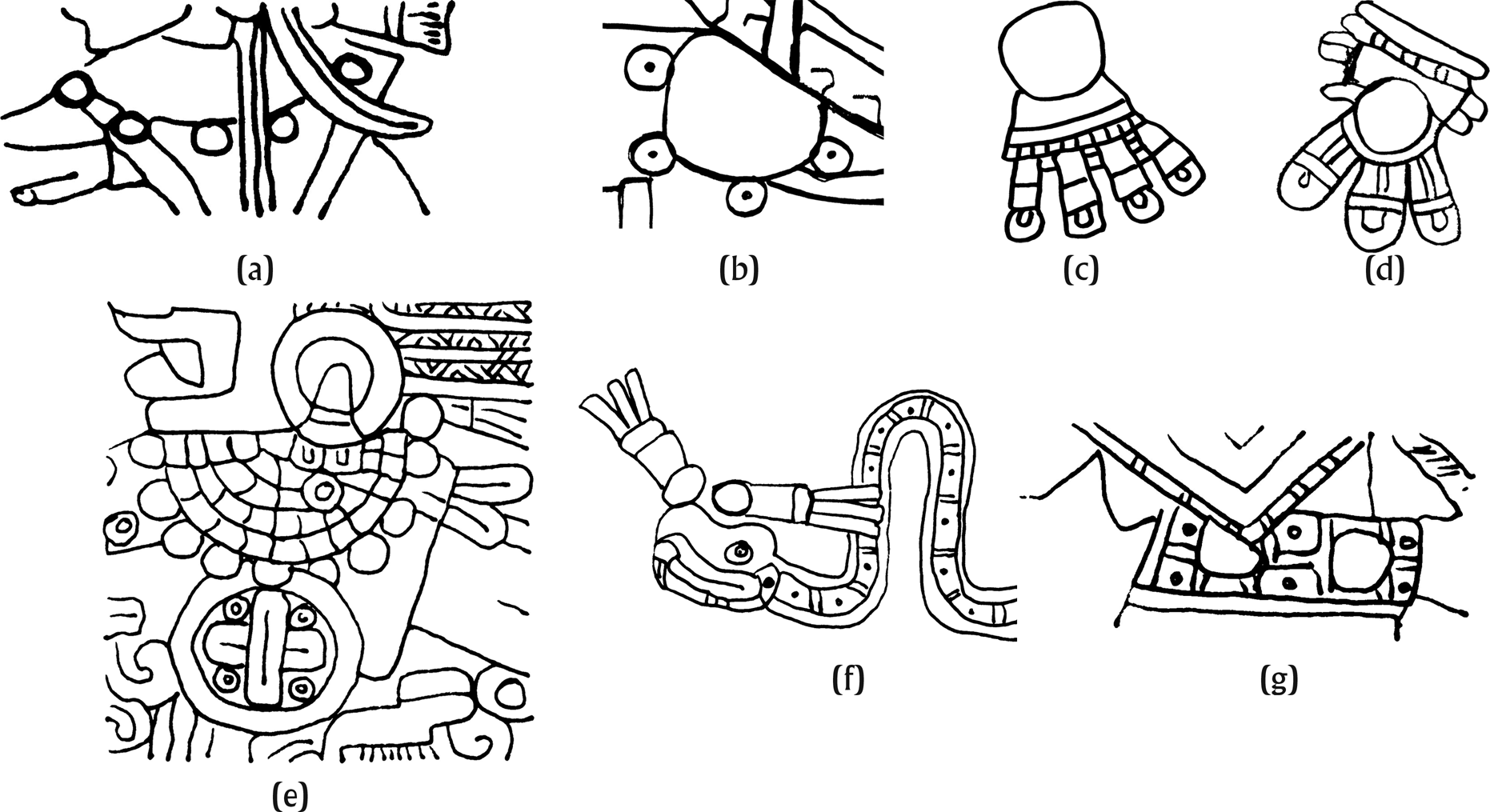

Figure 1. Toponymic glyphs for water in the Codex Mendoza (Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol. 3): (a) Anenecuilco (f. 24v); (b) Atzacan (f. 18r); (c) Acocozpan (f. 49r); (d) Atezcahuacan (f. 42r); (e) Teocuitlatlan (f. 44r); and (f) Hueyapan (f. 30r). (g) The elements of the glyph for water on a stream, Codex Borgia (Seler Reference Seler1988a:f. 65). (h) The water of the ritual bath for a royal investiture in the Florentine Codex (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1979:bk. 6, f. 34r).

Another comparable example is that of Atzacan: a[tl]-tzac[ua]-[c]an, “Place Where the Water Was Stopped.” The toponym is composed of two glyphs: a box closed by a hand that encodes the verb “to enclose,” “to stop” (tzacua, past tzauc), and the complete glyph for water (a[tl]) with stripes, spiral, and shell/water droplet edgings (Figure 1b).

Likewise, the toponym Acocozpan (a[tl]-co-coz[tli]-pan, “On the Yellow Water”) is composed of the glyph encoding the word “water” (a[tl]) including the usual elements, but reorganized around a spiral, filled with stripes and curves, and bordered by edgings that end in drops and shells surrounding them. The word “yellow” is encoded by the color being placed on the stripes, which are ordinarily painted blue (Figure 1c).

Nonetheless, the three elements of the water glyph are not always represented together. It can be understood that, theoretically, the following combinations exist: spiral + stripes; spiral + shell/water droplet edgings; stripes + shell/water drople edgings; or a single one of these elements represented separately (spiral alone, stripe alone, or shell/water droplet edging alone). I will now look at several examples derived from these possibilities.

Spiral and stripes are a combination appearing in the toponym Atezcahuacan: a[tl]-tezca[tl]-hua-can (“Place of Those Who Possess Water Mirrors”). It is composed of two glyphs, one encoding the word mirror (tezca[tl]) and the other encoding the word “water” (a[tl]) by means of a spiral made up of black and blue stripes (Figure 1d).

Stripes and shell water droplet edgings is the combination characterizing the toponym Teocuitlatlan: teo[tl]-cuitla[tl]-a[tl]-tlan (“In the Middle of Golden Water”), which refers to a stream where gold particles are found. It is composed of the glyph encoding “gold,” and that encoding “water,” reduced to its striped edgings ending with the characteristic water droplet and shell wave series (Figure 1e). The stripes standing alone characterize the toponym Hueyapan: huey-a[tl]-pan (“On a Large Body of Water”), made up of a circular shape striped with blue and black strokes (Figure 1f).

These few examples suffice to show that the water glyph is composed of elements that could be found together or used separately. What is remarkable is that it is also found in contexts not linked to the annotation of toponyms but in what are generally designated as iconographs. Thus, in the Codex Borgia (Seler Reference Seler1988a:f. 65), a stream spurts from the body of the Water Goddess. It carries the same three elements as the complete glyph for water in the Codex Mendoza: blue and black stripes, spirals, and wave edgings. The only difference is that the edging does not have the water droplet and shell tips characterizing the glyph in the Aztec manuscripts (Figure 1g). In the illustrations forming part of the work of Sahagún, water is represented by two of its elements, stripes and spirals, as it appears in the water that falls on the body of the king on the occasion of his investiture; so these traditional signs are integrated into a Europeanized representation (Figure 1h). I will now show that these three elements of the glyph for water are found scattered over the body of the Water goddess and embedded in her attire and ornaments.

The Glyph for Water in the Representation of Chalchiuhtlicue

The three elements that are used to represent water (stripes, spiral, and shell/droplet wave edgings) could either appear together or stand alone. It will be noted that these elements were embedded separately in different parts of the body of the Water goddess.

The blue and black stripes

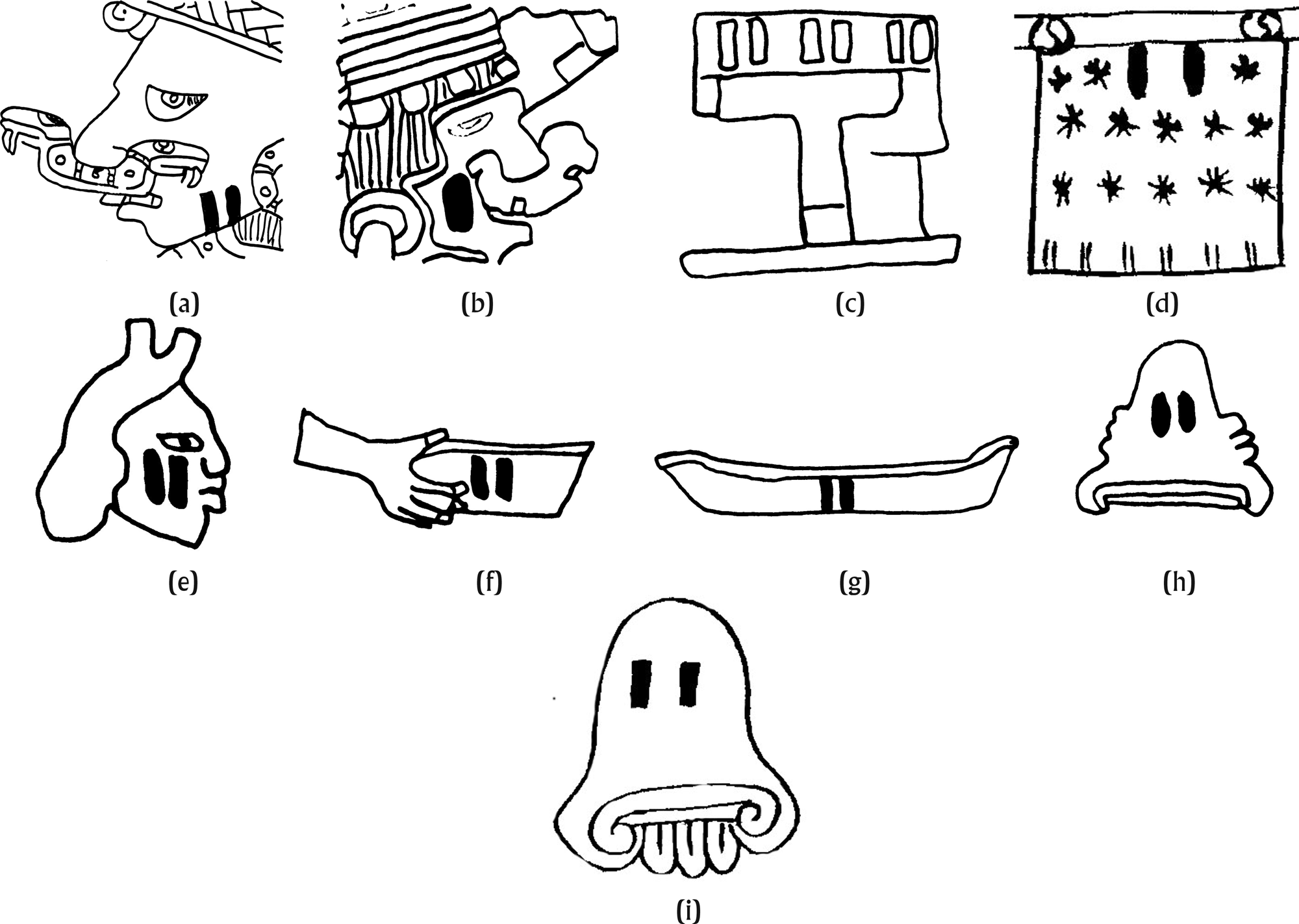

In the Codex Borbonicus, a pleated bark paper ornament appears at the top of Chalchiuhtilicue's head (Figure 2a). In statuary, it is found at the back of her neck (statue of Chalchiuhtlicue, Museo de América, Madrid, Inventory No. 2619). There its name is amacuexpalli (from ama[tl], paper, cuexpal[li], the lock of hair that fell from the occiput of children). The word designated a pleated neck ornament worn, for example, by the priests of Tlaloc (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 2, pp. 86–87), on which the black stripes were represented by the pleats in the blue paper.

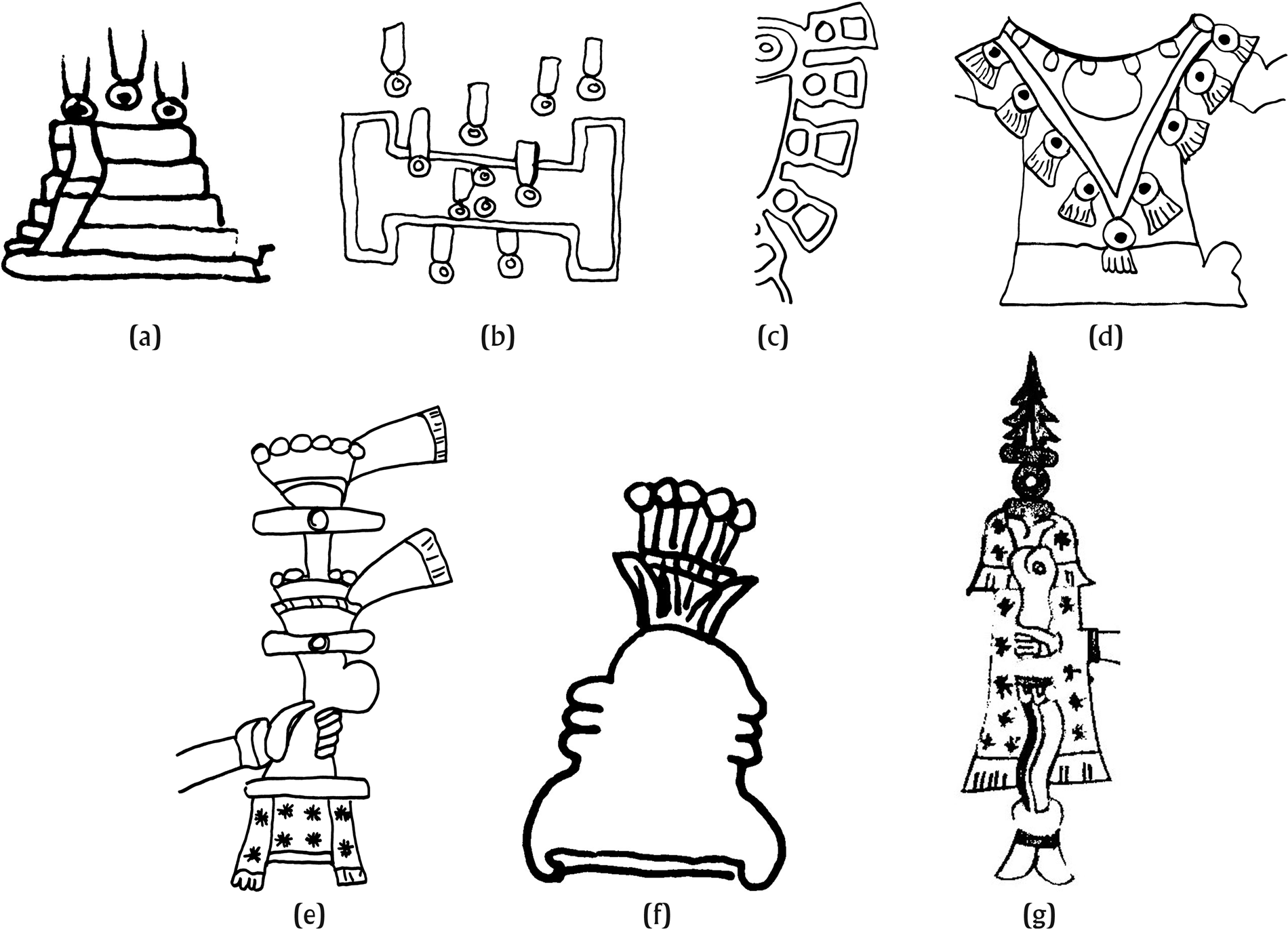

Figure 2. The elements of the glyph for water in Chalchiuhtlicue's ornaments. (a) The blue and black stripes in Chalchiuhtlicue's headdress in the Codex Borbonicus (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:f. 5). (b) The skirt of the Maya water deity in the Codex Trocortesianus (Anders Reference Anders1967:f. 30, cited by Seler Reference Seler, Eric, Thompson and Richardson1996:186). As found in the Codex Ferjeváry-Mayer (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1994a): (c) the white pulque spirals (ff. 7 and 8); (d) the white water spirals (ff. 3–4); (e) the white spirals on the hem of Chalchiuhtlicue's skirt and blouse (ff. 33–34); and (f) the headdress spirals (ff. 33–34). (g) The abbreviated form of Chalchiuhtlicue topped by the glyph for water in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis (Quiñones Keber Reference Quiñones Keber1995:f. 8v).

In addition, the blue paper headdress was often framed in quetzal bird feathers (Figure 2a), named “her headdress with a quetzal feather cluster” (iamacal quetzalmiahuayoh) in the Primeros Memoriales (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1993:f. 263v). This ornament, which represented the male flowering of corn (miahuatl), referred to this plant whose growth depended on the Water Goddess (Nicholson Reference Nicholson and Folge1963). Furthermore, quetzal-colored water designated a deep blue-green body of water (Quetzalatl; Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 11, p. 248), giving a double meaning to this ornament.

The spiral

Representing water by means of spirals (López Luján Reference López Luján1993:260) or Greek-like friezes, which are quadrangular spirals, is ancient and widespread in Mesoamerica and can be found in the Maya Codex Tro-Cortesianus or Codex Madrid (Anders Reference Anders1967; Figure 2b). Several examples of spirals are found in the Codex Fejerváry-Mayer. The surface of the liquids is topped by a frieze made up of small swirls (Figures 2c and 2d), found again on the hem of the skirt and in the shoulder shawl, named quechquemitl (Anawalt Reference Anawalt, Benson and Hill Boone1982:37), of the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue (Figure 2e). In addition, her headdress also is adorned with spirals, both in the form of vapor and in the movement of the quetzal feathers (Figure 2f). Finally, in the Primeros Memoriales (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1993:f. 263v), the attire of the goddess, a blouse and a skirt with the water designs (atlacuilolhuipil, atlacuilolcuei), are adorned with blue wavy lines punctuated by areas highlighting several spirals.

The wave edgings

We have seen, following the code used by the Aztecs, that the edgings take the form of waves whose tips consist of water droplets and shells. This element of the water glyph is found in the representation of Chalchiuhtlicue in a colonial manuscript of Aztec origin, the Codex Telleriano-Remensis (Figure 2g), in a passage in which the deities are represented in an abbreviated form: facing a day sign (on the right) is found the pictogram of the god (on the left) who intervenes in the role of “Lord of the Night,” in other words, the patron of a lapse of time. The transmission of this type of information is frequent in divinatory manuscripts (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Van der Loo1994b:142–160; Boone Reference Boone2007:96) and, due to the limited space available for each god or goddess, he or she is represented in a concise and undeveloped fashion. Generally, this shortened version of the deity consists of a face bearing the significant attributes—headdress, facial paint, ear ornaments—or the outline of a body bearing certain determinant forms such as necklace, pectoral, and other ornaments. In the Codex Telleriano-Remensis (Quiñones Keber Reference Quiñones Keber1995:f. 8v) and the Codex Vaticano A (Anders and Jansen Reference Anders and Jansen1996:f. 14v), Chalchiuhtlicue is depicted with a head bearing a blue paper headdress edged with a frieze of droplets and shells.

The three elements of the glyph are thus individualized when they cover the body of the goddess. It should also be recalled that there are ritual objects in which all three elements of the water glyph appear together, such as a feather shield representing water by means of stripes, spirals, and wavelets (Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City, in Castelló Yturbide Reference Castelló Yturbide1993; Filloy Nadal et al. Reference Filloy Nadal, Solís Olguín and Navarijo2007).

Rain Drops

A drop of water falling on the surface of water is a powerful image which has given rise to the invention of several glyphs.

Liquid Rubber Drippings

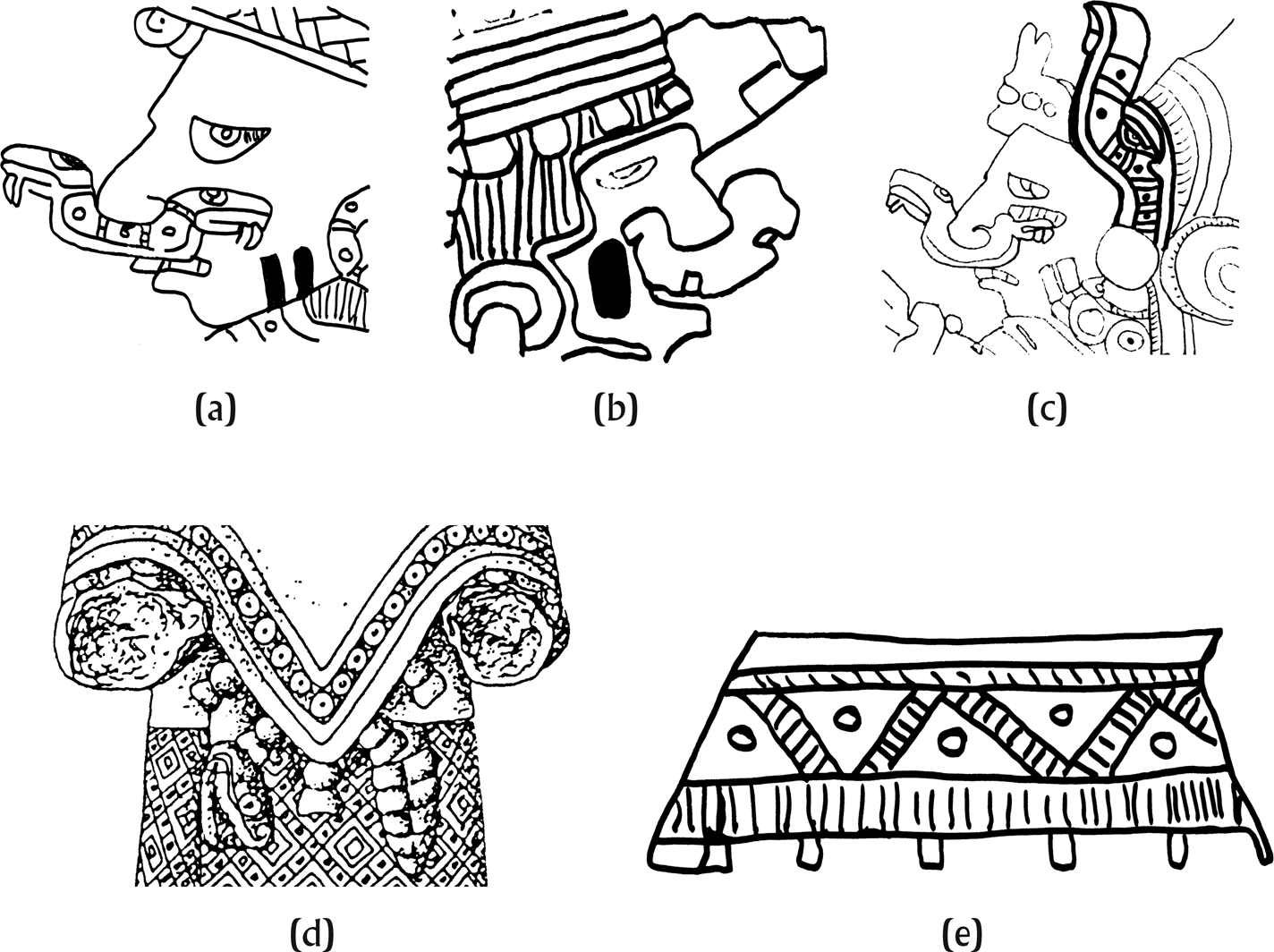

The rectangular-shaped cut of paper splattered with rubber drippings encodes the word tetehuitl, which has been translated as paper carried as a banner (Siméon Reference Siméon1977:520) or sacrificial banners (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 2, p. 89), paper banners (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 2, p. 154), and paper streamers (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 2, p. 42). This glyph is found in the toponym Teteuhtepec (tetehu[itl]-tepe[tl]-c, “At the Mountain with Tetehuitl”), in which the sacrificial paper is represented as a white rectangle splattered with rubber drippings (Figure 3a). This is also the way in which the Nahuatl texts defined tetehuitl: “the paper with rubber painting was called amatetehuitl or paper tetehuitl” (el papel con pintura de hule se llamaba amatetehuitl o tetehuitl de papel; Primeros Memoriales [Sahagún Reference Sahagún1993:f. 56, translated by Mikulska Dabrowska Reference Mikulska Dabrowska2015:449]). The distinguishing feature of the morphogram TETEHUI[TL], however, is the rectangular paper and not the type of design displayed on it, as a second toponym shows. Teteutlan (tetehu[itl]-tlan, “Among the Tetehuitl”) represents the sacrificial paper as a simple white paper rectangle without rubber drippings (Figure 3b). This is what led Carreón Blaine (Reference Carreón Blaine2006:113) to assert that the presence of these drippings is not the distinctive feature of the tetehuitl glyph.

Figure 3. Liquid rubber drippings as found in the Codex: (a) the toponym Teteuhtepec (Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol. 3, f. 7v) and (b) the toponym Teteutlan (Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol. 3, f. 46r). (c) A liquid rubber drops design in the Codex Magliabecchiano (Anders Reference Anders1970:f. 81r). (d) Chalchiuhtlicue's blue paper splattered with liquid rubber in the Codex Borbonicus (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:f. 5). (e) Chalchiuhtlicue's blue paper splattered with liquid rubber in the Codex Tudela (Tudela de la Orden Reference Tudela de la Orden1980:f. 13r).

These paper streamers, in fact, assumed numerous different shapes—tied to the crest of a mast, carried on the shoulders and calves of a ritual actor, enveloping the representations of miniaturized mountains, or the body of infants to be sacrificed– and were not exclusive to a particular category of deities (Mikulska Dabrowska Reference Mikulska Dabrowska2015:451–459). The designs that adorned them, however, were determinants of certain gods. An illustration from the Codex Magliabecchiano (Anders Reference Anders1970:f. 81r) shows that they could come in varied shapes and colors (red and blue). Chalchiuhtlicue, as is the case of several other rain deities, was recognizable in the black liquid rubber splattered over the paper object.

Is there a Nahuatl word to designate this design? The answer is yes, it is the drop of liquid rubber named tlaolchipinilli (tla-ol[li]-chipinilli, “rubber drippings”). The verb chipini or chichipini (with the doubling of the first syllable), which means “to fall drop by drop” or “drizzle” and describes a very fine sort of rain, is the root of the word chipinilli, “drop.” This gave rise to a numerical classifier allowing small measures of volume for a liquid to be counted, especially useful in medicine (centlachipinilli, ontlachipinilli…, “one drop, two drops…”). The rubber droplets named tlaolchipinilli are thus of a very small size. The Nahuatl texts sometimes associate them with the large drops known as tlaolchachapatzalli (tla-ol[li]-chachapatzalli, Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 2, p. 42. See also tlaolchipinilli [Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 1, pp. 17, 47, bk. 2, pp. 42, 88, bk. 9, p. 39] and tlaolchachaptzalli [Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 1, p. 47]). The latter name stems from the second of the frequentatives of the verb chapani (chachapani, “to rain large drops,” gotas grandes cuando llueve) and chachapatza (“to slosh through mud puddles,” chapotear por lodazales; Molina Reference Molina1966:316; Figure 3c).

From this linguistic analysis, we can conclude that the large and small liquid rubber drippings splattered over paper referred to rainy landscapes. The black color of these drops is explained by Dupey García (Reference Dupey García2010:vol. II, p. 435–426) who notes that Sahagún's informants describe the crown of the goddess Tzapotlan Tenan as splattered with large and small drops of liquid rubber (olli) and states that the liquid, whether transparent like the rain or milky white like pulque, is commonly represented by black-colored spots in manuscripts from central Mexico. As regards to Chalchiuhtlicue, she often wears a headdress and blue paper rosette at the back of her neck splattered with black rubber droplets (Figures 3d and 3e). It should be stressed that, unlike other tetehuitl which are of white-colored paper, the ornaments of the goddess are blue to refer to the color of the water, “obviously connected conceptually with flowing water, the particular sphere of the goddess” (Nicholson Reference Nicholson, Klor de Alva, Nicholson and Quiñones Keber1988:251). We can conclude that these ornaments are encoded generically by the tetehuitl glyph of sacrificial paper, but that their precise design corresponds to the Nahuatl words chipinilli and chapatzalli, “small and large drops.”

The Double Stroke-Sign and the “Hua Glyph”

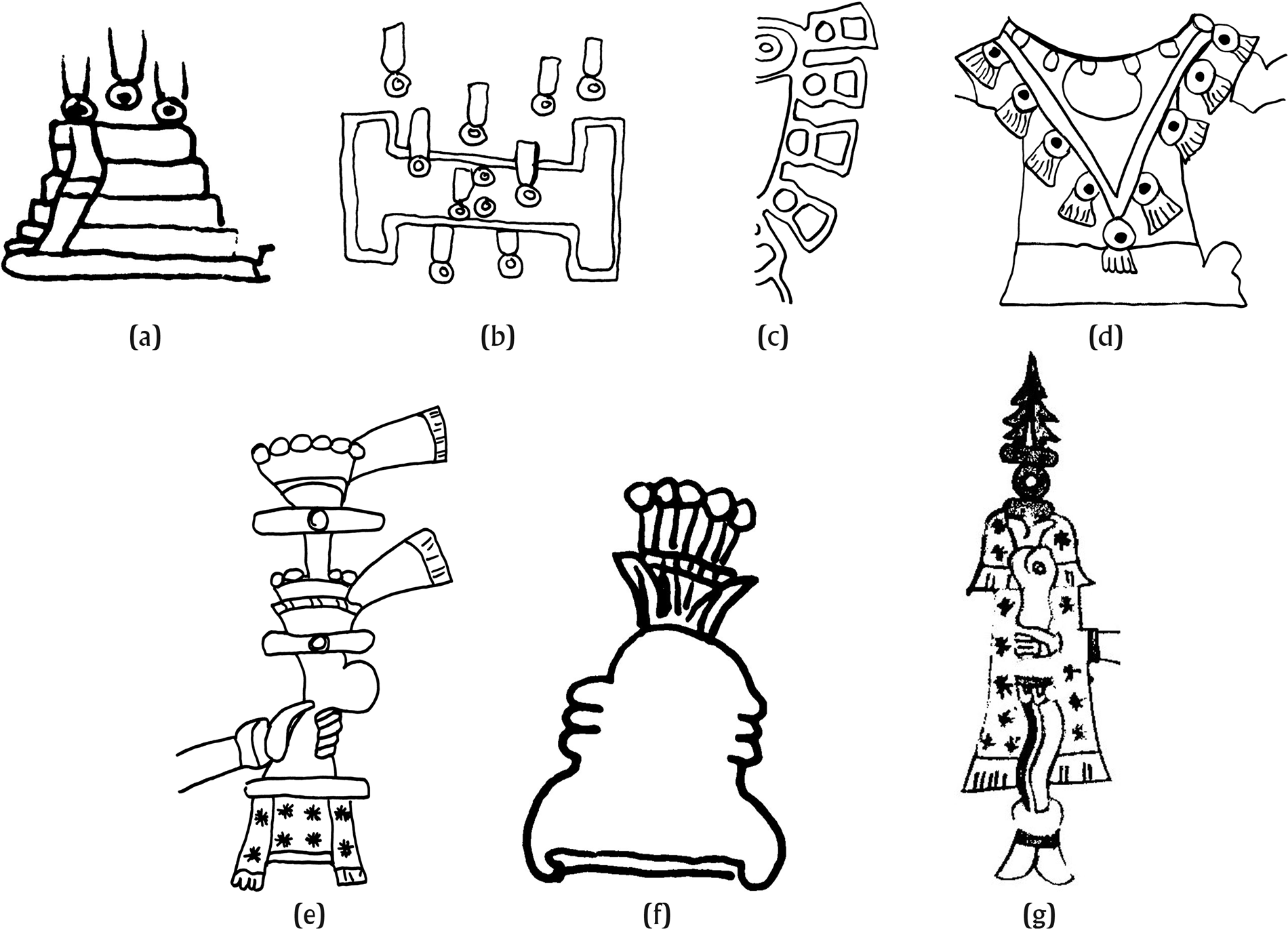

On a background of yellow face paint, two black marks adorn Chalchiuhtlicue's cheek in the Codex Borgia (“two short, wide intense black stripes, rectangular in shape” [dos franjas cortas, anchas, de contorno rectangular y de un negro intenso; Seler Reference Seler1988b: vol. I, p.80, my translation]; see also Figure 4a; Codex Borgia [Seler Reference Seler1988a:ff. 11, 14, 20, 65]). The abbreviated representation of the goddess, in the form of a face in the Codex Cospi (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Van der Loo1994b:ff. 1–8), is similarly adorned with the two black stripes. In the manuscripts of Aztec origin, they are sometimes abbreviated by a single black (Figure 4b; Codex Borbonicus [Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:f. 5]) or red (Codex Magliabecchiano [Anders Reference Anders1970:f. 75r]) mark. In statuary, the marks are hollowed out in the stone in two rectangular depressions in which rubber or black stone could have been deposited or inlayed. It can be added that this design systematically adorns the temples of pluvial deities (Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue; Codex Borbonicus [Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:f. 35]), and the “houses of mist” (ayauhcalco) specifically dedicated to Chalchiuhtlicue (Figure 4c; Mazzetto Reference Mazzetto2014:363–364, Figures 44–48), as well as several recipients found in the archaeological context of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan such as tepetlacalli (López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin and López Luján2009:321, 324), overturned pots (López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin and López Luján2009:367), and Chacmool (López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin and López Luján2009:44). Thus, they appear to be a distinctive mark of aquatic gods.

Figure 4. The double-stroke sign, as found in: (a) facial paint of Chalchiuhtlicue in the Codex Borgia (Seler Reference Seler1988a:f. 20). (b) Facial paint of Chalchiuhtlicue in the Codex Borbonicus (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:f. 5). (c) A “house of mist” or ayaucalli in the Codex Mendoza (Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol. 3, f. 64r). (d) Paper splattered with liquid rubber drops with the double-stroke sign in the Codex Magliabecchiano (Anders Reference Anders1970:81r, line 1, n°3). Examples from toponyms in the Codex Mendoza (Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol. 3): (e) Cihuatlan (f. 38r), (f) Xicalhuacan (f. 29r), (g) Acalhuacan (f. 17v), and (h) Tepexahualco (f. 36r). (i) Toponym in the Codex Huichapan (sign hui05v.04 in Wright Carr Reference Wright Carr2005:vol. II, p. 616).

Though these designs are not described by Sahagún's informants in association with Chalchiuhtlicue (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 1, p. 21), they are described with regard to the attributes of Tzapotlan Tenan, “Mother of Tzapotlan,” for which they were fashioned from bitumen, a black substance (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 1, p. 17). In the Nahuatl texts, the two rectangular designs are called ixahual ome quipillo, “her face paint consists of two suspended [drops]” (Seler Reference Seler1988b:vol. I, p. 80, my translation). For Seler, who bases his argument on this term, the two black bitumen or rubber marks represent drops of water, an interpretation adopted by Nicholson (Reference Nicholson, Klor de Alva, Nicholson and Quiñones Keber1988:252).

These short black stripes resemble the long stripes making up the glyph for water, together with the spirals and the tips ending in droplets and shells (Figures 1a, 1b, 1f, and 1g). They are characterized, however, by the fact that they “hang” (quipillo), which leads me to interpret them as drops, following Seler and Nicholson. The double-stroke sign is thus one of the numerous means to symbolize drops. This information is supported by the fact that certain sacrificial papers (tetehuitl) were adorned with both the liquid rubber drops and the two rectangular bars designs (Figure 4d).

Did the double-stroke sign receive a name in Nahuatl and could it have been encoded by a glyph? The answer is yes, and such a grapheme is found among the glyphs that make up certain toponyms of the Codex Mendoza. Several researchers have called it the “hua glyph” and Lacadena (Reference Lacadena2008b) has dedicated an article to it. This author identifies two phonetic signs, which he designates as wa1 and wa2 (in phonetic transcription). It is wa1 that corresponds to the double-stroke sign (Lacadena Reference Lacadena2008b:38–40) and it is present in four toponyms (Figures 4e–4h). I will return to the question of their identification recurring to what has been laid out above concerning the use of the sign in manuscripts with religious content.

The toponym Cihuatlan (cihua[tl]-tlan, “Among Women”) encodes the word “woman” (cihuatl) through use of a female face (Figure 4e). Why, then, does it have the double-stroke sign typical of Chalchiuhtlicue? Scholars who have addressed this issue have noted that the glyph is pronounced hua, or wa (depending on the phonetic transcription), which makes it a phonogram chosen for phonetic reasons. In the toponym Cihuatlan, it duplicates the syllable hua and thus acts as a “final phonetic complement” (Lacadena Reference Lacadena2008b:39), or as a “phonetic indicator, aiding in determining the correct value of the logogram in this context” (Whittaker Reference Whittaker2009:64).

The toponym Xicalhuacan (xical[li]-hua-can, “Place of They Who Possess Calabash Bowls”; Figure 4f) is composed of three glyphs: a calabash bowl (that encodes the noun xicalli, calabash bowl), a hand grasping the bowl (encoding the suffix -hua, which means “those who possess”), and the double-stroke sign. As the notion of possession is already indicated by the grasping hand (Lacadena Reference Lacadena2008b:41), the double-stroke sign has a purely phonetic value and duplicates the syllable hua, as in the case of Cihuatlan examined previously.

The toponym Acalhuacan (acal[li]-hua-can, “Place of They Who Possess Boats”; Figure 4g) is made up of a boat (encoding the word acalli, boat) over which is placed the double-stroke sign, which here encodes the suffix -hua, meaning “they who possess.”

In any case, the question can be raised as to the relationship between the phoneme hua in the toponyms and the use of the double-stroke sign in a religious context. The answer is that Chalchiuhtlicue is a female deity with face paint, which is enounced in the Nahuatl xahualli, a noun stemming from the verb xahua (to apply makeup). The yellow paint women applied to their face was often made from yellow ochre, tecozahuitl (Dupey García Reference Dupey García2010:vol. II, p. 414, citing Heyden Reference Heyden1983:135 and Seler Reference Seler1909:105). There was also a black paint made from bitumen (mochapopohxahua, “she paints herself with bitumen”; Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 8, p. 47) or from liquid rubber (olxahua, “she paints herself with rubber”; Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 4, p. 41), two substances that Carreón Blaine (Reference Carreón Blaine2016:31) considers analogous since they share several properties. It is the latter, tlaolxahualli, which characterizes Chalchiuhtlicue.

It can thus be seen that the phonetic value hua stems from the noun xahualli, “facial paint.” The scribes made the arbitrary choice of representing the word “facial paint” by means of a particular sort of paint, tlaolxahualli, facial paint from rubber, in the double-stroke sign. This hypothesis can be confimed in the description of the pot known as mixcomitl, “cloud pot,” which received the hearts of the sacrificial victims at the closure of the Etzalcualiztli feast. It was painted blue with black rubber spots: nauhcampa in tlaolxahualli, “it had [facial] painting on its four sides adorned with the black rubber double-stroke,” tlaolxahualli (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 2, p. 88). This proves that the term tlaolxahualli could be used in contexts other than that of feminine array to designate the double-stroke sign.

Another confirmation is found in the fourth toponym of the Codex Mendoza (Figure 4h), Tepexahualco (tepe[tl]-xahual[li]-co, “Place of the Facial Paint on the Mountain”). It is formed from the glyph that encodes the word tepe[tl], “mountain,” and the double-stroke sign that encodes xahual[li], “facial paint.” This means that, contrary to what Lacadena asserts (Reference Lacadena2008b:39), in this particular case the sign does not represent the phonogram wa (or hua) but, instead, the morphogram XAHUAL[LI]. This interpretation is supported by a toponym in the Otomi language, interpreted by Wright Carr (Reference Wright Carr2005:vol. II, p. 616) in the Huichapan Codex (sign hui05v.04) represented by the glyph for mountain, over which is placed the double-stroke sign (Figure 4i). According to the author, the toponym is accompanied by a gloss in Otomi, amatshobo amats'obo, which can be translated as: “Place of the Facial or Body Paint” (lugar de la pintura corporal o facial).

We can thus conclude that the glyphs making up the toponyms of the Codex Mendoza are two in nature: morphogram (XAHUAL[LI], “facial paint”) and phonogram (hua). In all cases, though, they are derived from the ritual representation of the two black rectangles that adorn the face of certain female deities. The morphogram XAHUAL[LI]), “facial paint,” is taken directly from the religious image and it can be posited that its abbreviation hua, whose purpose is to form a phonogram, is a derivation of it. It can likewise be thought that the phonogram hua is derived from the verb huahuana (“make lines in the earth, make lines on paper”; Molina Reference Molina1966:607), following a hypothesis advanced by Lacadena (Reference Lacadena2008b:40). In this case, it would stem from a double derivation, xahualli and huahuana.

In its ritual and original form, the double stroke-sign (called tlaolxahualli) represented a falling raindrop, while the drippings of liquid rubber on paper (called tlaolchipinilli) were a depiction of the raindrop hitting the ground. These two signs thus provided two complementary ways of designating rain.

The Rain Glyph

The representations of Chalchiuhtlicue are often completed by the glyph known to encode the word quiahuitl, “rain,” in different toponyms. For example, it is found in the Codex Mendoza in the place name Quiauhteopan (quiahu[itl]-teopan, “Temple of the Rain”; Figure 5a) and in the Codex Telleriano-remensis, it is one of the components of the toponym Tlachquiauhco (tlach[tli]-quiahu[itl]-co, “Ball Game of the Rain), the name of the present-day city of Tlaxiaco in the state of Oaxaca (Figure 5b). The glyph for rain consists of a single drop of water hanging from the tip of a cylinder, probably describing its falling movement.

Figure 5. The rain glyph and other evocations. (a) The toponym Quiauhteopan in the Codex Mendoza (Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol. 3, f. 8r). (b) The toponym Tlachquiauhco (Tlaxiaco) in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis (Quiñones Keber Reference Quiñones Keber1995:f. 41r). (c) The hem of Chalchiuhtlicue's shawl in the Codex Borbonicus (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:f. 5). (d) The hem of Chalchiuhtlicue's shawl and (e) yauhtli flowered stick in the Codex Magliabecchiano (Anders Reference Anders1970:f. 58r). (f) Toponym Yauhtepec in the Codex Mendoza (Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol. 3, f. 24v). (g) Chalchiuhtlicue's rattle stick in the Codex Tudela (Tudela de la Orden Reference Tudela de la Orden1980:f. 13r).

In religious contexts, the glyph is inverted and the cylinder is positioned at the end of the drop. This is how I explain “the two large tassels attached to the sides of the heads of most of the numerous stone images that appear to represent this goddess” (Nicholson Reference Nicholson, Klor de Alva, Nicholson and Quiñones Keber1988:249, 250, Figure 31; see also Stresser-Péan Reference Stresser-Péan2011:146, Plate 21). I am also of the opinion that the tassels attached to the edging of the shoulder shawl, or quechquemitl, of the goddess, represent the inverted glyphs for rain (Figures 5c and 5d). In fact, in everyday life, Aztec women dressed with a huipil and the shoulder shawl was worn only in ritual contexts: “[a]ll of the symbolism connected with the quechquemitl associates the costume with fertility and abundance, an association that appears to exist throughout Central Mexico” (Anawalt Reference Anawalt, Benson and Hill Boone1982:41). Furthermore, the edgings of the quechquemitl worn by the Aztec goddesses were often decorated with fringes, or tassels made by bunching these fringes together (Stresser-Péan Reference Stresser-Péan2011:80, 83). The tassels bordering the quechquemitl and the two tassels on either side of the tiara are systematically depicted in the statues of the goddess (López Luján and Fauvet-Berthelot Reference López Luján and Fauvet-Berthelot2005:Statues 10–17). It logically follows that they constituted more than one attribute carrying a simple ornamental function and possessed a symbolic meaning attached to the feminine world of fertility.

Other Renderings of Rain

Finally, mention must be made of the instruments wielded by the goddess. In the manuscripts of Aztec origin, one of her hands holds a stick adorned with yauhtli or iyauhtli flowers, Tagetes lucida, known as flor de pericón in Spanish (Figure 5e; see also Figure 3e). The yellow flower clusters are arranged in a bunch in characteristic fashion. In addition to Chalchiuhtlicue, other rain deities such as Tlaloc and Huixtocihuatl hold them in their hand (López Luján Reference López Luján2006:vol. I, p. 216; Sierra Carrillo Reference Sierra Carrillo2007:60–61; Taube Reference Taube, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000a:278–280). They evoke the incense made from dried yauhtli burned with copal. The two materials produce a cloud of smoke resembling the clouds preceding the rain. Thus, the bunch of flowers also makes up a glyph that appears in the toponym Yauhtepec (yauh[tli]-tepe[tl]-c, “At the Mountain with Tagetes lucida”; Figure 5f). The bunch is thus a ritual item that can be used as a glyph in a place name.

Chalchiuhtlicue's other hand held an ayauhchicahuaztli (ayahu-[itl]-chicahuaztli, “mist rattle stick”). Several deities possessed rattle sticks but only rain gods had specifically “mist” rattle sticks and mist in Nahuatl was ayautli (a[tl]-yauhtli, “water Tagetes lucida incense”). In other words, mist was conceived of as droplets of smoke. The rattle stick represented has the form of a serpent, the symbolism of which will be explained below, and is enveloped in blue pieces of paper splattered with liquid rubber, attributes particular to the water deities (Figure 5g). On the occasion of ceremonies, the person who personified the goddess shook this percussion instrument, producing a noise that imitated that of falling rain. This sound was accompanied by the tinkling of bells worn around the ankles (itzitzil; Primeros Memoriales [Sahagún Reference Sahagún1993:f. 263v]), thus reinforcing the association with rain.

We can conclude that the presence of water on Chalchiuhtlicue's body assumed several different forms: the liquid element was represented by the stripes, spirals, and shell/droplet edgings; the rain by different types of drops; and metaphoric forms such as the use of Tagetes lucida flowers and the rattle stick completed the picture. What is striking is that all the designs examined so far served as components of toponymic glyphs.

Jade (chalchihuitl)

The goddess was called Jade Her Skirt, a name constructed by means of a metaphoric shift, a mental procedure based on the similarity of certain properties of both water and jade. The iconographic representation of jade can inform us of the nature of these analogies. It furthermore confirms that the inhabitants of central Mexico did whatever possible to diversify representations of jade, as they did with water.

The Pierced Jade Stone

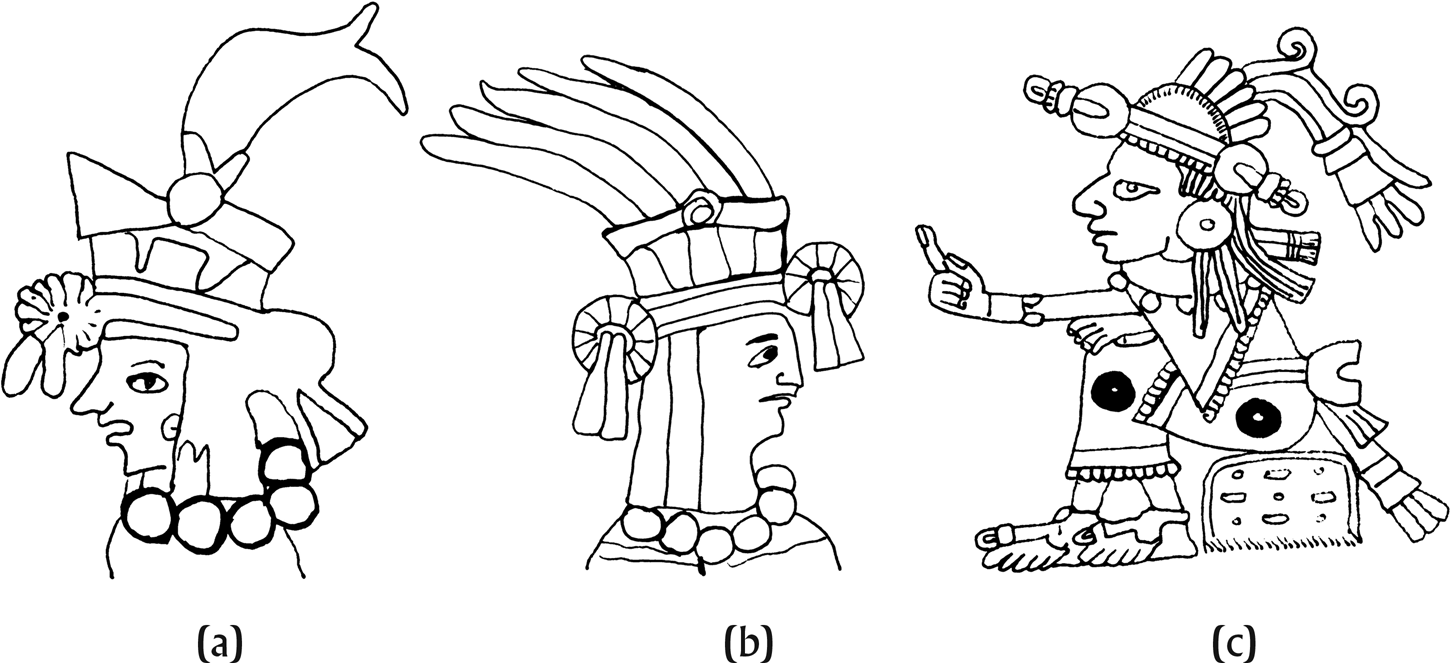

The word jade (chalchihuitl) could designate the precious mineral jadeite, as well as numerous objects made from the mineral, such as the fine polished sheets known as tlacanahualli (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 11, p. 223), mosaic masks (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 2, p. 159), pendants, nose pieces and, above all, oblong objects and beads whose center had been pierced by a jeweler to be worn in a necklace, bracelets, or earrings (Stresser-Péan Reference Stresser-Péan2011:180–184). The same Nahuatl term “jade” (chalchihuitl) was applied to all these forms. It seems, however, that jade was mainly equated with “pierced stone.” According to Nicholson (Reference Nicholson and Benson1973:5), Tovar (Reference Tovar1944:18, 22) found the toponym Chalco to be a derivative of challi (“a hollowed-out cavity like a mouth,” un hueco a manera de boca). In López Luján's opinion (personal communication 2017), the word could stem from the verb chaloa, “to open,” as in “to open one's mouth,” by extension meaning “to pierce.” Although the word challi is not found in the dictionaries, Berdan (Reference Berdan, McEwan and López Luján2009, Reference Berdan, López Luján and McEwan2010:216) asserts that chalchihuitl means “what has been pierced” in Nahuatl. This seems to be the case in the iconography of Chalchiuhtlicue in which the jade bead appears: heavy necklaces worn on the sculptured images, around the neck of the impersonators of the goddess, and as a symbol found in portrayals of the goddess in the divinatory codices (Figures 6a–6c). Nonetheless, jade could likewise be represented in the form of a jewel itself, such as the necklace and bracelet in the Codex Fejerváry-Mayer (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1994a:f. 10). This image designated the jewel by means of the color of the stone, regardless of its real shape: set of stones, breastplate, or sheets (Stresser-Péan Reference Stresser-Péan2011:180–184). Furthermore, the white mother-of-pearl disks seem to have provided an infrequent alternative to jade beads (Codex Borgia [Seler Reference Seler1988a:f. 20, for example]) and they are arranged at the front of a headband (Seler Reference Seler1988b:vol. I, p. 80). Another rare alternative is turquoise, replacing jade in the goddess's earring, according to the Primeros Memoriales (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1993:f. 263v; xiuhnacochtli, xihu[itl]-nacoch[tli], “turquoise ear ornaments”).

Figure 6. Jade beads (a) in a necklace in the Primeros Memoriales (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1993:f. 263v), (b) in a necklace in the Florentine Codex (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1979:bk. 1, f. 5), and (c) in an ear ornament and in a sign affixed to the goddess's skirt in the Codex Fejerváry-Mayer (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1994a:ff. 9–10).

The Glyph for Jade

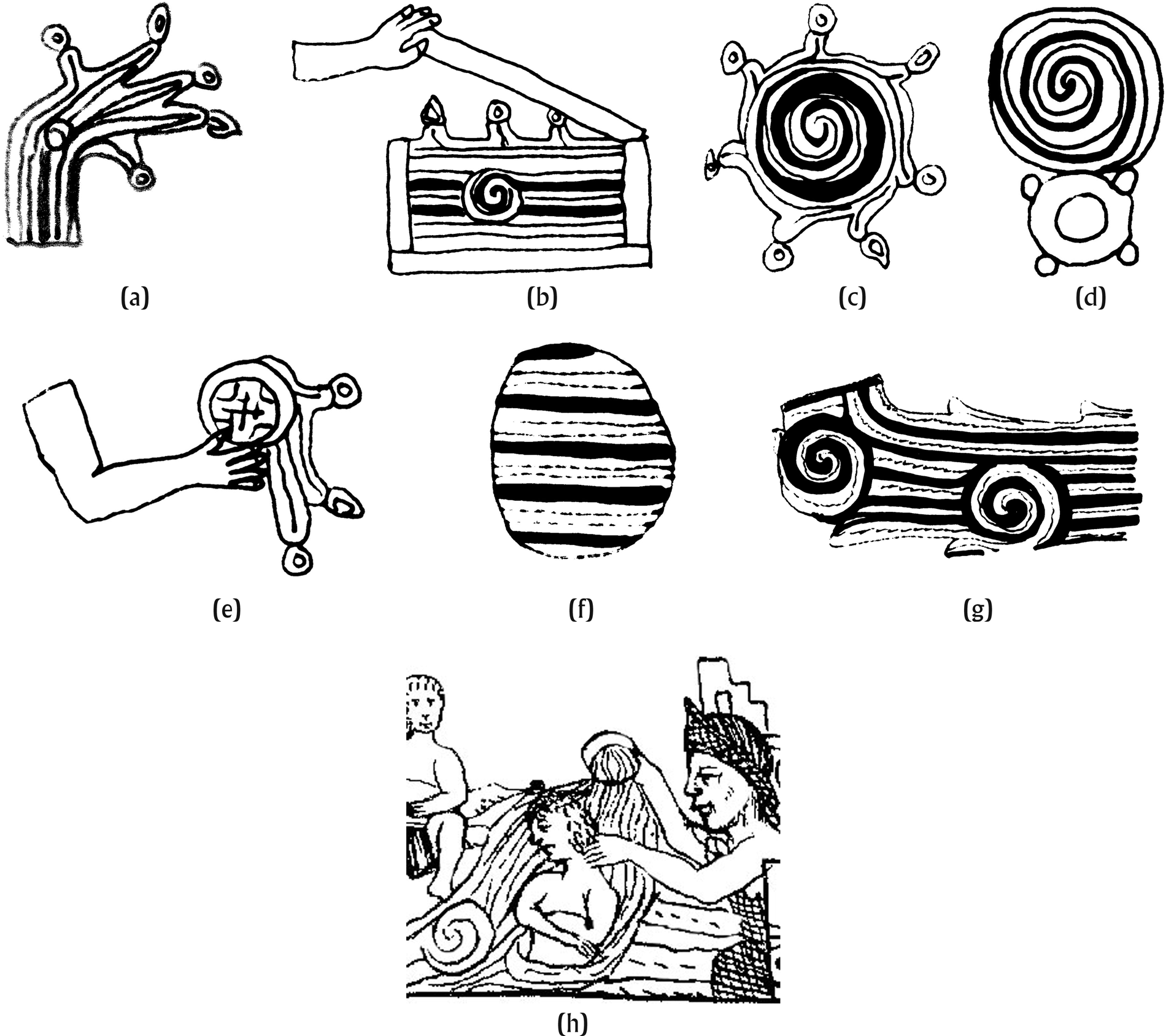

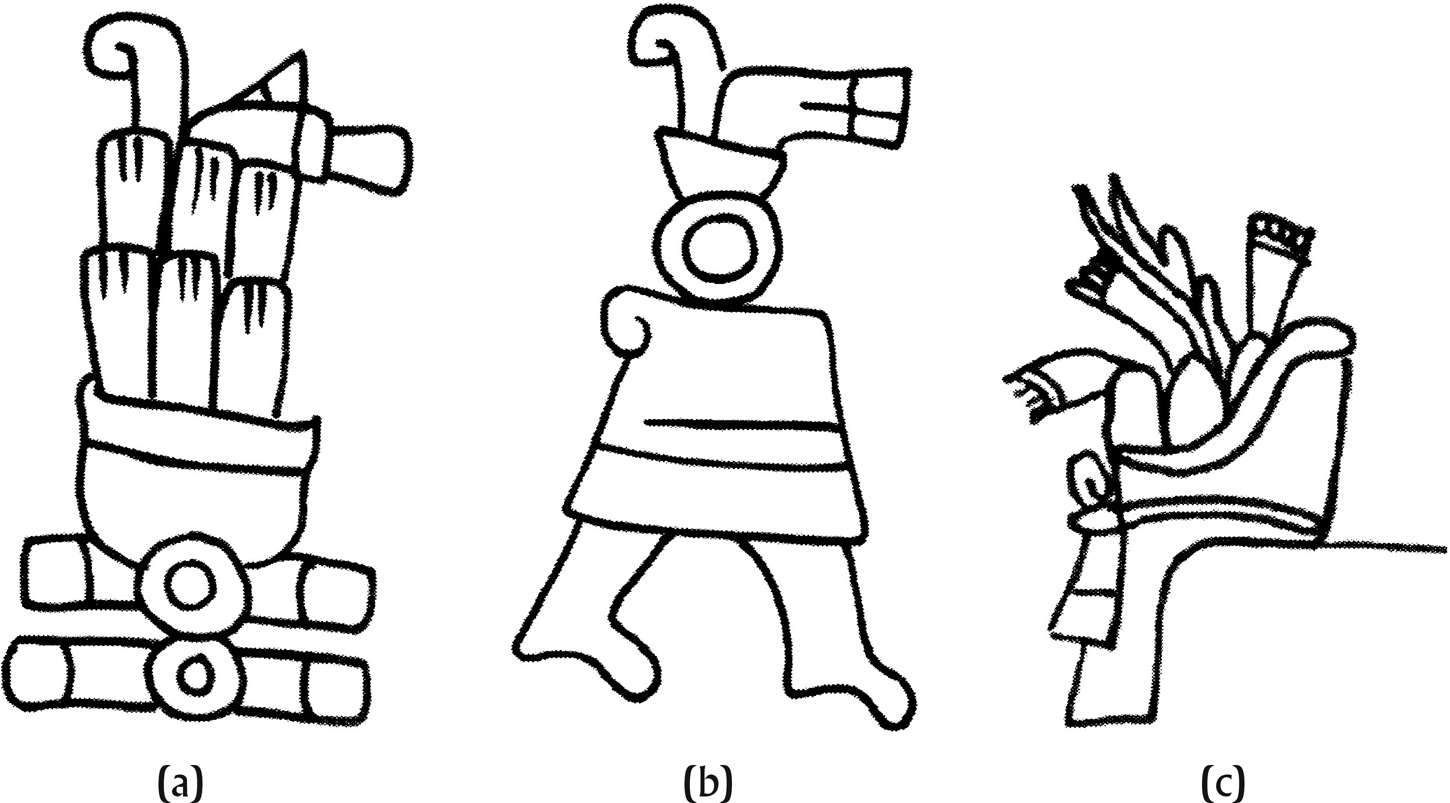

Another way to represent jade was to use its glyph, present in certain toponyms, particularly in the Codex Mendoza. The glyph for jade (Figure 7a) is the conventional depiction of a sphere-shaped object in whose green center lighter shades are painted. It is circled in red followed by a white circle decorated with designs and flanked with four drops of water (Thouvenot Reference Thouvenot1982).

Figure 7. The glyph for jade and its variants. (a) Glyph for chalchihuitl in the toponym Chalco in the Codex Mendoza (Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol 3., f. 41r). (b) Chalchiuhtlicue necklace (curved shape) and earring (elongated shape) in the Codex Borbonicus (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:f. 5). (c) Chalchiuhtlicue's skirt with the three colors in the Codex Fejerváry-Mayer (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1994a:ff. 3–4). The 1 signifies green, the 2 signifies red. (d) Elongated shape of gold earring (López Luján Reference López Luján2015:Figure 6, Type 20; McEwan and López Luján Reference McEwan and Leonardo López2009:299).

If jade is sometimes represented in this manner in the ornaments of the gods, it also comes in a series of variants that evoke it through different shapes and colors. The following possibilities can be mentioned: a curved shape with the sequence of the three colors of the glyph (green, red, and white) and ending with drops; an elongated shape with the three colors (Figure 7b); or the three colors affixed to any flat, linear surface (Figure 7c). Figure 7d is of interest because it shows that jade could be depicted in its elongated shape alone, without colors. Specifically, these two gold ear ornaments were uncovered in the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlán (Ofrenda 125) in the context of a ritual deposit (López Luján Reference López Luján2015:32). The existence of variants in the conventional representation of jade thus provided an array of possibilities for whoever wished to depict the chalchihuitl through its different shapes (circular, curved, and elongated) and hues.

The Jade and Gold Association

As Vauzelle (Reference Vauzelle2017) has recently shown, among the ornaments worn on the chest, gold was frequently associated with jade. Besides the case in which the necklace is exclusively of jade, depicted by its glyph as we have seen above (Figure 7b), it could also consist of jade bordered by gold beads (Figure 8a). Hanging under the necklace is a disk, either of jade bordered by gold beads (Figure 8b), or gold with jade pendants (Figures 8c and 8d), i.e., reversing the procedure. When the disk was made of gold, it was called a teocuitlacomalli, “golden plate,” according to Seler (Reference Seler1909). Chalchiuhtlicue was frequently depicted with a golden disk on her chest, but this is also the case of nine other deities (Vauzelle Reference Vauzelle2017).

Figure 8. Jade and gold. (a) Jade necklace with gold beads in the Codex Fejerváry-Mayer (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1994a:ff. 7–8). (b) Jade pectoral with golden beads in the Codex Fejerváry-Mayer (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1994a:ff. 33–34). (c) Gold pectoral with jade glyph in the Codex Borbonicus (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:f. 5). (d) Gold pectoral with jade glyph in the Codex Borbonicus (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:f. 35). (e) Tlaloc pectoral with gold glyph from the Watering Tlaloc in the British Museum (López Luján Reference López Luján2014:Figure 17). (f) The gold glyph affixed to a serpent in the Codex Borgia (Seler Reference Seler1988a:f. 11). (g) Gold disk and jade bead on a gold glyph background in the Codex Borgia (Seler Reference Seler1988a:f. 20).

What is of interest here is the variety of representations of the teocuitlacomalli. We have seen above that jade can be represented as a pierced green stone as well as by means of its glyph. Gold also has its own glyph, which is used in the Codex Mendoza to represent toponyms that contain the word “gold,” such as Teocuitlatlan (teo[tl]-cuitla[tl]-a[tl]-tlan, “In the Middle of Golden Water”), discussed above (Figure 1e). The glyph for gold is a large circle with a cross and four small circles. As with the glyph for jade, it is frequent in representations of a religious nature and in toponyms alike.

Figure 8e exemplifies a case in which the glyph indicates that the pectoral disk is of gold. This representation is carved on the four sides of a stone casket (tepetlacalli) conserved in the British Museum (McEwan and López Luján Reference McEwan and Leonardo López2009:53), part of the collection of objects attributed to the Aztec sovereign Ahuitzotl. The anthropomorphic figure represents one of the four assistants of the rain god Tlaloc. He wears a gold pectoral known as a teocuitlacomalli on his chest, depicted as a stone circle containing the glyph for gold.

As in the case of other glyphs, it also has its variants. For example, it can lose its circular shape and be represented on a flat surface by a succession of non-contiguous rectangles enclosing a small circle or dot (Figure 8f). In the Codex Borgia, just such a design often adorns serpents but can also be found affixed to Chalchiuhtlicue's skirt. In Figure 8g, the goddess's skirt evidences the association of gold with jade, depicted by a yellow disk and a pierced green stone, respectively. The background consists of the glyph for gold (a succession of rectangles and circles) painted red. The question can be raised as whether the glyph for gold has an alternative or additional meaning in this case. It is found, in fact, in the Codex Borgia in places where it seems to mean “serpent.” It is affixed to numerous serpents and the attire of Chalchiuhtlicue and Tlaloc in this codex to the extent that Heyden (Reference Heyden1984:28–29) refers to them as “serpentine designs” (diseños serpentinos). I analyze this topic in the following section devoted to reptiles.

Terrestrial and Aquatic Reptiles

The serpent is one of Chalchiuhtlicue's attributes, first of all in a nose plug in the shape of a two-headed serpent (Figure 9a) found in the Codex Borgia, from which, according to Seler, the blue sheet in the form of the Greek-like frieze is derived: “[a]s a nose plug, our goddess [in the Codex Fejerváry-Mayer (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1994a:f. 3)] wears a scaled blue sheet and, not, as in the figure in the Codex Borgia, the two-headed serpent, that is perhaps the embryonic form that was at the base of the development of the scaled sheet” (Seler Reference Seler1988b:vol. I, p. 170; my translation). In other manuscripts, however, Chalchiuhtlicue occasionally wears a yacapapalotl, a nose plug in the form of a stylized butterfly, as it seems to be the case in Figure 9b. Actually, that plug is typical of another goddess, Xochiquetzal (Nicholson Reference Nicholson, Klor de Alva, Nicholson and Quiñones Keber1988:252; Seler Reference Seler1988b:vol. I, p. 158), and I believe that its presence on Chalchiuhtlicue occurs when, for certain reasons, the goddesses are brought together. An alternative hypothesis can be postulated that the two forms of nose plugs are fused together—the scaled blue sheet representing the two-headed serpent and the stylized butterfly evoking Xochiquetzal—to become a distinctive element of Chalchiuhtlicue.

Figure 9. Serpent-shaped motifs. (a) Serpent-shaped nose plug in Codex Borgia (Seler Reference Seler1988a:f. 20). (b) Greek-like frieze nose plug in the Codex Borbonicus (Anders et al. Reference Anders, Jansen and Reyes Garcia1991:f. 5). (c) Serpent-jaw helmet in the Codex Borgia (Seler Reference Seler1988a:f. 11). (d) Rattlesnake waistband, statue of Chalchiuhtlicue, Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City (inventory number 10-82215 in Stresser-Péan Reference Stresser-Péan2011:146). (e) Triangle frieze on Chalchiuhtlicue's skirt in the Codex Borgia (Seler Reference Seler1988a:f. 20).

Furthermore, the face of the goddess is often depicted emerging from a helmet in the form of a serpent's head (Figure 9c; Olivier Reference Olivier and Carrasco2001:173; Seler Reference Seler1988b:vol. I, p. 80). I have stated above that the design representing gold on a flat surface consisting of a rectangle followed by a circle often covers the bodies of serpents in the Codex Borgia (Figure 8f). This design is found on several of the elements of Chalchiuhtlicue's attire, for example on the body of the serpent forming her helmet (Figure 9c). The serpent also characterized the Water Goddess in the sculptures: in a statue Chalchiuhtlicue's skirt is held in place by a waistband in the form of a rattlesnake, whose head and rattles hang from the knot (Figure 9d). Finally, a rhomboid-shaped design typical of the turtle, or a triangular shape, a variant of this, sometimes appeared on the skirt of the goddess (Figure 9e; Mikulska Dabrowska Reference Mikulska Dabrowska2008:187–191).

The presence of serpents on Chalchiuhtlicue's body is not surprising. The serpent, particularly the rattlesnake, is an ancient Mesoamerican symbol with multiple meanings associated “with the different cosmic levels. Accordingly, they have been seen in the popular imagination as projected across the sky in the form of wind, lightning[,] and the rainbow. Their movement has been compared with flows and cycles, including those referring to time. They have been the symbol of fertility and blood” (López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin and López Luján2009:274, my translation). So serpents have a pluvial association, among others (López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin and López Luján2009:153–154), which explains why the part of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlán dedicated to Tlaloc was decorated with ondulating serpents (López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin and López Luján2009:274–278). Ophidians thus accompany the gods of rain and the earth.

Serpents and turtles are depicted among the toponyms of the Codex Mendoza. The serpent (coa[tl]) is found in numerous place names such as Coatlan (coa[tl]-tlan, “Among the Serpents”; Codex Mendoza [Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol. 3, f. 23r]) or Mixcoac (mix[tli]-coa[tl]-c, “Place of the Cloud Serpent”; Codex Mendoza [Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol. 3, f. 5v]), and the turtle (ayo[tl]) is the stem of the toponym Ayotlan (ayo[tl]-tlan, “Among Turtles”; Codex Mendoza [Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Rieff Anawalt1991:vol. 3, f. 47r]), to mention only a few cases. The examples support the observation made above: the elements of the code that refer to the Water Goddess also appear as toponymic glyphs. This raises the question of how we can explain this apparently intrinsic link between religious manuscripts and systems of notation and bearing of this relationship on a theory of pictographic signs in central Mexico.

FROM THE REPRESENTATION OF THE DIVINE TO THE TOPONYMIC GLYPH

As we have seen above, scholars generally distinguish between images that transmit information as icons and graphic signs that encode words. These categories, however, have been called to question by some authors, one of whom is Elkins (Reference Elkins1999:83, cited in Mikulska Dabrowska Reference Mikulska Dabrowska2015:337), who speaks of a continuum between the painted and the written. In spite of the Western tendency to class all visual artifacts as either image/design or writing, there are no pure cases: “rather than speaking about glottographic, logographic, phonographic, syllabic, phonetic systems, etc. […] it would be more fruitful to speak of systems that function by making use of different operating principles in different proportions” (Mikulska Dabrowska Reference Mikulska Dabrowska2015:351, my translation). The matching of the distinctive signs of the gods and the glyphs making up the toponyms provide a further element of evidence for this debate. It supports the idea that separating image and writing into two distinct categories is unsuitable for Mesoamerica. I will now show that there was a single system of signs but that these signs had different functions depending on the manuscript.

A Single Repertoire of Signs

Excepting the Codex Fejerváry-Mayer, drawn by scribes in an unidentified language, the remaining manuscripts analyzed here were probably drawn by Nahuatl speakers. I have attempted to shed light on a certain number of signs that refer to the person of the Water Goddess through the use of toponymic glyphs: water (stripes, spirals, shell/water droplet edgings); rain drops (sacrificial papers and their liquid rubber drippings design, facial paint and its double-stroke sign, and rain); jade (pierced stone and chalchihui[tl] glyph); gold (gold disk in which gold can be indicated by the color yellow or the teocuitla[tl]glyph); Tagetes lucida flower (yauh[tl]I glyph); and reptiles (serpent glyph and turtle glyph).

The same conventions were applied to the Water Goddess: stripes, the spiral, and the shell/water droplet design edging (Figures 2a–2b, 2e–2g), facial paint (Figures 4a and 4b), jade (Figures 6a–6c, 7b–7c), gold (Figures 8a–8e, 8g), and serpents (Figures 9a–9e). To express these ideas, however, signs that were specific to one of these codices, such as the serpent-head helmet (Figure 9c), were sometimes used and the design standing for gold was represented on a flat surface by the succession of the rectangles and circles (Figures 8f and 8g). For their part, the manuscripts from central Mexico likewise had their own peculiarities and used certain signs, absent to my knowledge in the Borgia and Fejerváry-Mayer codices: the sacrificial paper (tetehuitl; Figures 3d and 3e), the rain glyph (quiahuitl), and the Tagetes lucida flowers (yauhtli; Figures 5c–5e). It is only natural that the different manuscripts used different specific styles. My research shows, however, that there were fewer particularities than might be expected and that the distinctive signs of the Water Goddess formed a relatively homogeneous whole.

My approach to the analysis of the signs involved spreading them out along a continuum in which one extreme consisted of the images of the deities and ritual objects actually used in the ceremonies in their honor, with the other made up of glyphs that can encode toponyms. What I found through this method is that we are in the presence of a relatively unified system covering varied domains of application.

Previous research followed the tendency, pointed out above, to separate images from script. This is why the phonogram hua (wa) of certain toponyms of the Codex Mendoza had thus far not been explained. Only by relating toponyms to the religious iconographic tradition of Chalchiuhtlicue's facial paint (xahualli), including those in the manuscripts of the Borgia Group, can the glyphs from those toponyms be deciphered correctly (Figure 4). This example shows that the right approach, which could lead to fruitful results, would be to consider all these signs as part of a single system.

Notational and Magical Functions

My assertion that these signs constitute a single system does not mean that they do not have important differences in regard to their function. It could be posited that the toponyms respond to a notational function, while the distinctive signs of the Water goddess have a magical function. I will now proceed to look at these functions in search of the reasoning behind their specificities.

The Notational Function

Toponyms are characterized by a notational function. As is to be expected, the morphograms and phonograms are used to write names, titles, the socio-political designation of persons, and place names so as to achieve precision in reading (Whittaker Reference Whittaker2009:59). This is what explains the characteristics of the toponyms.

Enunciation

This involves delivering a message in the clearest possible manner so that it can be read. A toponym is thus linked to the language and is drawn to be pronounced. This explains why the term “facial paint” (xahualli) produced the phonogram hua in a context of notation, in other words, through a change in its function.

The economy of means

The message must be as brief as possible. We can assume that when the water glyph, which normally contains three elements (stripes, spirals, and wavelets), is represented by use of one or two of the three, it is to obtain an uncluttered depiction of the toponym.

The reading order

A toponym in the Codex Mendoza has its place in a series of toponyms organized in accord with the reading order: the head town of a tributary province of the Aztec empire is at the top of the list, followed by the names of all the other towns in descending order. The toponym thus defined is opposed term-by-term in antagonic fashion to the signs with a magical function.

The Magical Function

I will borrow here the term used by Mikulska Dabrowska (Reference Mikulska Dabrowska2015:322–334), who maintains that the functions of the different archaic writing systems throughout the world are principally magical and divinatory. While Mikulska Dabrowska emphasizes divination because she studies divinatory manuscripts, I stress the magical function, more appropriate when speaking of depictions of deities. The term ritual efficacy could also be used to refer to the fact that the representation of certain signs produces the effect sought by the performance of the ceremonies. Mikulska Dabrowska (Reference Mikulska Dabrowska2015:323) mentions the case of the sacred diagrams of the Buddhist mandalas, the Navajo sand paintings, the Tibetan banners covered with writing that float in the air, and the amulets bearing words inside them. All these cases are examples of the magical or ritual efficacy function, exactly like the conventional signs scattered over the Water Goddess's body. It follows that these signs exhibit certain characteristics.

Optional enunciation

In the magical function, ritual efficacy is contained primarily in the representation. This does not mean that the spoken word is necessarily absent from the ritual (the performance of the impersonator of a god can be accompanied by chants), but it is not a necessary condition. In this sense, this characteristic of the magical sign is in opposition to the obligation of enunciation found in the notational function.

The search for redundancy

This feature is the opposite of that of the economy of means characteristic of the notational function. While the latter favors the brevity of the message, reiteration of signs constitutes an essential aspect of magical efficacy. This is what explains the search for diversity shown in Table 1. Water is represented there by its three elements (stripes, spirals, and shell/water droplet edgings) indicated separately; depiction of the rain is obtained by means of three signs (paper splattered with liquid rubber, facial paint, and the rain glyph); and jade was represented by the pierced stone, or the glyph varying in curved, tubular, and flat shapes. To depict gold, the choice was between a yellow disk and one containing the glyph representing gold. The same thing could be expressed in several different ways. Why was this? Because magical efficacy required repetition, it was necessary to increase the designs, to affix them, above all, on the body of Chalchiuhtlicue and literally inundate her body with her attributes. The magical function demanded repetition and redundancy, principles present in ancient Mexican iconography which Mikulska Dabrowska (Reference Mikulska Dabrowska2010:331, 335, 337) has termed “communicative accumulation.”

The incorporation of the sign in the divine body

This aspect is opposed to the reading order characterizing the signs with a notational function. The signs embedded in the body ornaments of the goddess not only do not follow a set reading order, but they are inserted in all possible items of dress and attire. Their shape is what often determines where they were placed. Accordingly, on a necklace, the glyph representing jade was depicted in a curved shape and in a tubular one on an ear ornament. The logic of where the signs were placed also responded to a corporal diagram that attributed semantic values proper to each part of the body (e.g., head, chest, and hands; Vauzelle Reference Vauzelle2014).

It should be noted that the magical function of the glyphs was perhaps present in Teotihuacan art as López Luján suggests (personal communication 2017). In fact, some of the glyphs found in mural painting and ceramic “theatre” censers are also found on the human body, the mountains, or the gateway to the afterlife, without following a preestablished sequence (Langley Reference Langley1986, Reference Langley and Berlo1992).

Thus, the difference between religious signs and toponyms lies not in the nature of the designs, but in their function, magical in the one case and notational in the other.

THE PRINCIPLES OF REPRESENTATION OF THE GODDESS

Having passed review of the designs included in Table 1, I will now turn my attention to the semantic groups indicated in the same table. It will be recalled that the designs are classed in conceptual sets: water, rain, jade, gold, and reptiles.

Definition of Water by Extension

I have argued elsewhere (Dehouve Reference Dehouve2013, Reference Dehouve2014b, Reference Dehouve2014c), that the semantic unit of Mesoamerican ritual discourse is not the word but the association of several words in “series,” which define a thing, a being, or an action through the enumeration of its components or manifestations. According to the French dictionary (Robert Reference Robert2008:989, “Extension”), there are two ways to define a word. “Definition by extension” expresses a whole through the enumeration of its parts: “[e]xtension of a word refers to the totality of the beings or things designated by this name.” Thus, for example, to define the word “man,” a series of men may be listed (e.g., Peter, Paul, and so on). “Definition by extension” must be distinguished from “definition by intension,” which, conversely, sets forth the “set of characteristics belonging to a concept,” i.e., in the case under consideration, the attributes that men have in common, such as upright posture and language.

The ancient Mexicans made frequent use of definitions by extension, i.e., the enumeration of the components of an entity and the manifestation of a phenomenon. As one example of the many metonymic series in Nahuatl that I have studied (Dehouve Reference Dehouve2014b), the phrase “the flowers, the tobacco, the loincloth, the cape, the weaving, the clothes, the land, the house” (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 6, p. 106) constituted an enumeration which, in modern languages, must be translated by a more synthetic term. As the men returning from battle with captives for sacrifice were recipients of various kinds of luxury goods, accordingly, the series of these goods designated “honors achieved in war.” The first two terms of this series (the diphrasism flowers/tobacco), and even a single term (flower or tobacco), could stand for the complete series, expressing the synthetic notion “honors achieved in war.”

The idea that the ancient Mexicans had of the water deity, Chalchiuhtlicue, was expressed by the same means, through a metonymic series of chosen manifestations that constituted the semantic groups: water, rain, jade, gold, and reptiles. This manner of expression was a way of responding to the question: what is water? Recurring to a definition by extension involved enumerating a series of characteristics of the element recognized in the culture.

Water Is a Blue-Green Surface

Among the names for rivers and streams reported by Sahagún's informants are Amanalli (a[tl]-mani, “The Water Lies Flat”; Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 11, p. 250) and Axoxohuilli (a[tl]-xoxohui-lli, “Green Water”; “[t]his is a cavern of water which is just flat; the very deep one; the green one. It lies green”; Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 11, p. 251). The color green thus referred to a quality attributed to deep water, known as “green water,” “water cave,” or “big deep” (axoxohuilli, aoztotl, huecatlan; Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 11, pp. 248, 251), that the Aztecs represented in the form of pleated paper and quetzal feathers (Figure 2a).

Water Is Constantly Moving

According to the Nahuatl texts in the Florentine Codex, the most characteristic trait of water is its incessant movement. Thusly, on the occasion of her birth ritual, a baby girl was invited to be like the water incarnated by Chalchiuhtlicue, always active and awake (Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 6, p. 206). This is because the paradigm of water is the spring, from which the movement stems. Certain Nahuatl verbs such as meya, ameya (to spout), moloni (to flow), momoloni (to bubble), momoloca (to froth from shaking or boiling), and apatzca (to trickle) are part of the root words for nouns designating springs: ameyalli, moloyan, apapatzalan, and apatzquitl. Regarding a river or stream whose source is a spring (atoyatl), it is known as “the one who spouts” (meyani), “who bubbles” (molonini), “who goes fast” (totocani), “who runs” (motlaloani), “who runs roaringly” (zolonini), “who gurgles” (xaxamacani; Anderson and Dibble Reference Anderson and Dibble1950–1982:bk. 11, pp. 247–251). This quality was expressed by the spiral in Chalchiuhtlicue's ornaments (Figures 2b–2f).