INTRODUCTION

In the literature on ethnically divided societies, minority rule is considered a liability for the state and a driver for political instability. Rebellions are more likely to occur against regimes that exclude large segments of the population based on ethnic background (Roessler Reference Roessler2011; Wimmer, Cederman, and Min Reference Wimmer, Cederman and Min2009). As a result, ethnically dominated regimes are perceived as less stable and more prone to breakdown (Cederman, Gleditsch, and Buhaug Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013, 1; Harkness Reference Harkness2018). However, while ethnically dominated regimes may fuel greater collective grievances (Leipziger Reference Leipziger2024), many of these regimes demonstrate considerable resilience in the face of resulting opposition challenges. For example, all regimes that faced large-scale popular mobilization during the Arab Spring of 2011 were overthrown, except for the minority regimes in Bahrain, Jordan, and Syria.Footnote 1 Similarly, the Togolese regime, in power since 1963, has suppressed with deadly force several major popular protests that attracted hundreds of thousands of participants.

This article examines the remarkable resilience of a specific type of ethnically dominated autocracy. I find that minority regimes that exclude a single majority ethnic group exhibit exceptional durability and immunity from outsider anti-regime challenges. Prominent examples of such autocracies are the Togolese regime, which has been in power since 1963; the RPF regime in Rwanda, which has been in power since 1994; and the Apartheid South African regime. On average, these regimes have remained in power more than twice as long as other autocracies. Most importantly, they demonstrate greater durability when confronted with significant challenges outside the regime. This is remarkable because while historically more dictatorships fell to coups than to other forms of challenges, overthrows by popular uprisings and revolutions have become increasingly common, especially since the end of the Cold War (Beissinger Reference Beissinger2022; Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright, Wright and Frantz2018, 179).

I argue that the durability of this type of minority autocracy is rooted in its unique ethno-political configuration, which enables it to foster a largely unconditional loyalty due to the ruling minority’s fear of being subjected to majoritarian rule. Such heightened threat perception, in turn, generates three dynamics that strengthen the regime: (1) the demobilization of the ruler’s ethnic group, which engages in policing and sanctioning dissenting coethnics; (2) coethnic counter-mobilization, which involves the mobilization of civilian supporters and militias from the ruler’s ethnic group who actively participate in repression; and (3) cohesion among coethnic elites, enabling the regime to deploy the military in repression without fear of defections.

To evaluate these theoretical claims, I employ a mixed-methods research design. First, I statistically evaluate the theory using data on authoritarian regimes’ breakdown between 1900 and 2015 and data on challenges against authoritarian regimes from 1945 to 2013. I find that minority regimes with an excluded majority group are almost three times more likely to survive in power than other authoritarian regimes. In addition, challenges against such minority regimes are seven times less likely to succeed compared with challenges against other regimes. Second, a case study of Bahrain allows me to elucidate the logic behind these findings and the causal mechanisms. I draw on interview data collected during my fieldwork in Bahrain, Lebanon, and London (UK).

This article makes several important contributions. First, it represents the first systematic attempt to theorize and empirically analyze minority autocracies. Conflict studies have rightly focused on minorities as vulnerable groups who are “at risk” and subject to exclusion and discrimination (Gurr Reference Gurr1993). However, minorities that control the state and exclude other groups, including majority groups, are often overlooked. Second, this study bridges the gap between studies of conflict and authoritarianism. While the former suggests that ethnically dominated regimes are more prone to instability (Bodea and Houle Reference Bodea and Houle2021; Cederman, Gleditsch, and Buhaug Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013), scholarship on authoritarian regimes expects them to be more durable as they rely on the support of loyal coethnic elites (Allen Reference Allen2020; Harkness Reference Harkness2021; Morency-Laflamme Reference Morency-Laflamme2018). I reconcile these conflicting views by highlighting the conditions under which ethnic loyalty can enhance regime survival and longevity.

Third, my examination of political loyalty goes beyond the extant literature, which has focused on the material sources of loyalty, including patronage networks (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2011; Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Wintrobe Reference Wintrobe2000), economic performance (Reuter and Gandhi Reference Reuter and Gandhi2011; Shih Reference Shih2020), and power-sharing arrangements (Meng Reference Meng2020; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Scholarship on the role of nonmaterial ties and threat perceptions in generating loyalty tends to be elite- and state-centric (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2022; Slater Reference Slater2010). By contrast, I examine ethnic loyalty and threat perceptions at the group level, thereby highlighting the role of societal mechanisms that underpin regime survival. Therefore, following the “institutional turn” in the study of authoritarianism (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2004; Geddes Reference Geddes1999; Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2014), this study attempts to bring society back in. I build on an earlier tradition concerning the social origins of democracy and dictatorship (Collier Reference Collier1999; Moore Reference Moore1966; Rueschemeyer, Stephens, and Stephens Reference Rueschemeyer, Stephens and Stephens1992; Wood Reference Wood2000) and recent scholarship on the role of social actors in authoritarian control (Mattingly Reference Mattingly2020; Ong Reference Ong2022; Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2020).

LITERATURE AND THEORY

Recognizing that autocracies relying on material forms of loyalty vary significantly in their durability, the literature increasingly highlights the importance of nonmaterial sources of regime cohesion. An extensive body of literature explained elite loyalty and regime survival through the mechanism of authoritarian distribution (Albertus, Fenner, and Slater Reference Albertus, Fenner and Slater2018), including the co-optation of political elites via the sharing of spoils (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2011; Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Siverson and Morrow2003; Gandhi and Przeworski Reference Gandhi and Przeworski2007; Lust-Okar Reference Lust-Okar2006) and the incorporation of societal groups through state employment and other economic benefits (Liu Reference Liu2024; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006; Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2020). However, while access to spoils may secure elite loyalty in normal times, it is often inadequate during crises, such as economic shocks and mass mobilization (Houle, Kayser, and Xiang Reference Houle, Kayser and Xiang2016). Therefore, Levitsky and Way (Reference Levitsky and Way2012) argue that regimes combining patronage mechanisms with strong identity-based ties exhibit greater durability. Similarly, Slater (Reference Slater2010) emphasizes the importance of “protection pacts”—elite cohesion based on shared perceptions of endemic threat—over “provision pacts,” which are based on patronage and spending.

These perceived threats and the resulting solidarity ties can arise from various factors. Violent social conflicts can unify political elites due to a shared fear of being overthrown by their rivals. For instance, revolutionary and counter-revolutionary regimes, which face violent conflicts during their founding periods, often develop stronger solidarity ties and elite cohesion (Clarke Reference Clarke2023; Lachapelle et al. Reference Lachapelle, Levitsky, Way and Casey2020; Slater and Smith Reference Slater and Smith2016). Rebel regimes are also more durable because shared armed struggle and intense security threats provide a foundation of stable and credible power-sharing agreements (Meng and Paine Reference Meng and Paine2022). External threat (Alsaadi Reference Alsaadi2023), ideological ties among elites (Le Thu Reference Le Thu2018; Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2022, 39), and ideological polarization between elites and their rival opposition (Lachapelle Reference Lachapelle2022) can also play a significant role in regime strength and elite loyalty.

Ethnic identity represents another marker of cohesive group formation and a potent source of nonmaterial loyalty. Building on an earlier tradition of ethnic loyalty in divided societies (Decalo Reference Decalo1990; Enloe Reference Enloe1980; Goldsworthy Reference Goldsworthy1981; Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985), recent scholarship has emphasized the practice of “ethnic stacking,” which involves recruiting coethnics into state institutions and particularly into security forces and the military (Harkness Reference Harkness2018; Morency-Laflamme and McLauchlin Reference Morency-Laflamme and McLauchlin2020; Roessler Reference Roessler2011). Coethnics are assumed to be more loyal, requiring less monitoring, and are thus preferred in senior positions (Hassan Reference Hassan2020). In addition, this identity marker instills a sense of fear that their fates are linked with the regime (Bellin Reference Bellin2004); they “stand or fall with the dictator” (Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright, Wright and Frantz2018, 164). By cultivating greater elite loyalty, ethnic stacking can reduce the risk of military coup (Allen Reference Allen2020; Brooks Reference Brooks2013; Harkness Reference Harkness2021; Morency-Laflamme Reference Morency-Laflamme2018) and enable the repression of anti-regime challenges (Leipziger Reference Leipziger2024). This prompted scholars to attribute the military’s loyalty in Syria and Bahrain during the Arab Spring of 2011 to the countries’ sectarian diversity and the regimes’ strategy of recruiting personnel from minority ethnic groups (Albrecht Reference Albrecht2015; Makara Reference Makara2013).

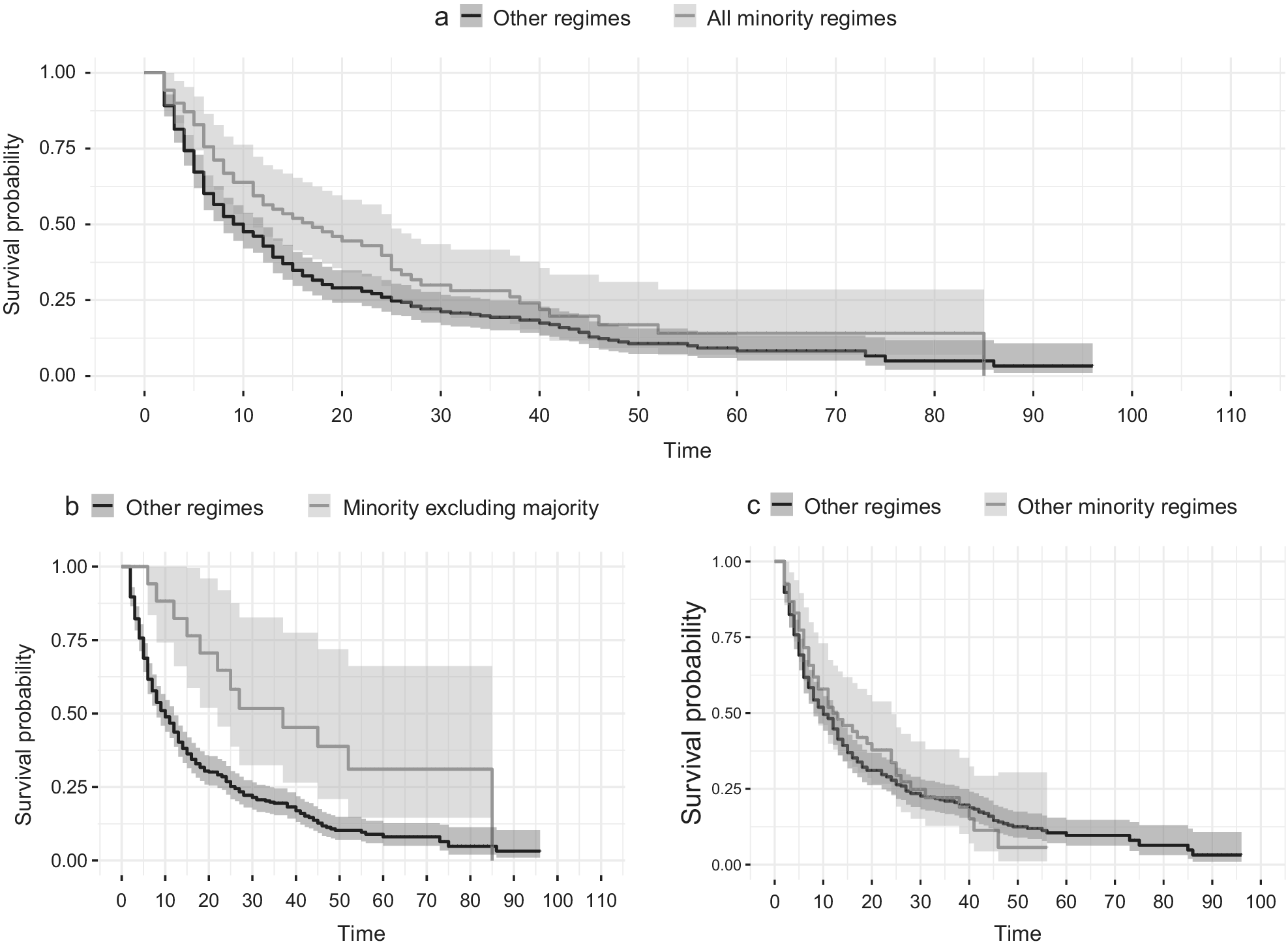

However, a significant variation exists in the durability of ethnically dominated regimes and in the loyalty of their coethnic elites. For example, during the protest wave in Sub-Saharan Africa from 1989 to 1993, many autocrats found themselves unable to employ their militaries in repression, leading to their eventual ousting (Bratton and Van de Walle Reference Bratton and Van de Walle1992). Similarly, my original dataset of minority autocracies, which I detail below, shows that durability is not a given for all minority regimes (Alsaadi Reference Alsaadi2025). Figure 1 compares the survival rates of minority regimes to those of other autocracies from 1900 to 2015. Panel a shows that minority regimes survive longer than nonminority autocracies (p = 0.02). However, panel b reveals that this trend is driven by a specific subset of minority rule: minority regimes that exclude a single majority ethnic group. Examples of these autocracies include the regimes in Bahrain, Assad’s Syria, and Apartheid South Africa. The 25-year survival rate for such regimes is 58%, significantly higher than the 25% survival rate observed in other regimes (p < 0.001). Conversely, the remaining minority regimes shown in panel c do not exhibit a reduced risk of collapse, indicating that neither ethnic diversity nor minority status alone ensures authoritarian longevity.

Figure 1. Survival Curves: Autocratic Regimes (1900–2015)

Therefore, we cannot assume that ethnic recruitment automatically leads to high threat perception and greater loyalty. The lack of conditional accounts to ethnic stacking is surprising, given the constructivist turn in comparative politics that distinguishes between the social fact of ethnic diversity and the salience of ethnic cleavages, which stems from various contextual factors rather than any inherent characteristics of identity itself (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004; Chandra Reference Chandra2006; Posner Reference Posner2005). Understanding the specific conditions under which ethnic group loyalty plays an important role in autocratic survival is crucial. In the next section, I offer an account that highlights the importance of relative group size and ethnic composition in generating threat perception and salient group identity among minority regimes.

Minority Autocracies

Minority autocracies are regimes controlled by members of an ethnic group that constitutes a numerical minority within the country. In such cases, the rulers disproportionately recruit from their own minority group for key positions in state institutions, especially within the military and security services. The origins of many of these regimes can be traced back to their colonial legacies. Colonial powers frequently implemented recruitment policies favoring specific ethnic minority groups in the military and colonial administrations. This strategy, aimed at establishing loyal support bases within the local population, was documented in various regions, including Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, laying a foundation for minority rule in many countries post-independence (Blanton, Mason, and Athow Reference Blanton, Mason and Athow2001; Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985, 445; Kirk-Greene Reference Kirk-Greene1980; White Reference White2011; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2015, 42; Wimmer Reference Wimmer2002, 95).

Building on the previous discussion that highlights the importance of both threat perception and contextual understanding of ethnic identity, I argue that the durability of certain minority regimes, such as those in Bahrain, Syria, and Apartheid South Africa, is rooted in their unique ethno-political composition. These are regimes controlled by members of a minority group that excludes a single majority ethnic group, which generates high threat perception and fear among members of the ruling minority of being subjected to majoritarian rule.

In states ruled by members of a minority group that excludes a majority ethnic group, an authoritarian breakdown can be perceived as very costly, as it threatens the status of the ruling minority. For example, the introduction of Black suffrage during the 1870s in certain Southern states where African Americans were a majority triggered a fear of “Negro domination” among the white minority, who largely perceived multiracial democracy as an existential threat and opposed it fiercely (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2023, chap. 3).

Similar feelings of threat among dominant minorities can be generated during periods of popular challenges to minority regimes, wherein the challengers demand power sharing on the basis of electoral results that will almost definitely not favor the ruling minority group. In societies with a majority ethnic group, the latter is unlikely to agree to institutional power sharing (i.e., formal ethnic quotas) and will likely demand sharing power on the basis of elections that can reflect the relative size of each group (Nomikos Reference Nomikos2021). This engenders a sense of fear and uncertainty, which is often a crucial factor in the formation and preservation of salient identities and political groups (Evrigenis Reference Evrigenis2007; Hastings Reference Hastings1997).

In this sense, it is not the minority character of the regime per se that produces cohesion and loyalty but rather the face-off with a single excluded majority. Therefore, ethnic fractionalization within the excluded majority also affects threat perception. In countries with high ethnic fractionalization, where no single ethnic group holds a majority, the excluded population is fragmented across multiple ethnic groups (e.g., in Sudan, Benin, and Malawi). These are minority regimes that exclude other minorities. In such a context, the fact that “no one group is able to single-handedly monopolize political power” encourages elites to accept political transition (Fish and Kroenig Reference Fish and Kroenig2006, 168). For example, during the 1992 uprising against Banda’s regime in Malawi, ethnic fragmentation influenced the regime’s calculations. Regime elites opted to hold elections, anticipating that forming coalitions with other ethnic groups and dividing the opposition vote would help them preserve their influence in the new political landscape (Venter Reference Venter and Wiseman2002). In contrast, defecting from a ruling minority to a single, homogeneous majority risks absorption and marginalization, leading to a heightened fear of change and, thus, stronger group cohesion.

Before we examine the causal mechanisms in the following section, it is important to distinguish ethnic minority regimes from other forms of minority rule, commonly discussed in the literature. While all authoritarian regimes are minority arrangements and fear takeover by an excluded majority (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006), the minority character of the regime is insufficient to produce elite loyalty if defined in broad political or class terms. First, fear of the majority’s distributive demands by a wealthy minority of elites can be mitigated by factors such as inequality levels, capital mobility, and the size of the middle class (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Boix Reference Boix2003; Lipset Reference Lipset1959). In addition, negotiated transitions often allow elites from the old regime to preserve their privileges and even dominance in the new regime (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Riedl Reference Riedl2014; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2022). Second, this distributive model has been criticized for weakly resembling the actual dynamics of authoritarian regimes and democratization (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2012), especially in postcolonial states (Slater, Smith, and Nair Reference Slater, Smith and Nair2014) where nonclass cleavages, including ethnic identity, play a significant role in shaping regime outcomes (Clarke Reference Clarke2017). Ethnicity, unlike class or political affiliations, carries a psychological and cultural bond rooted in shared history, language, and social networks (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2004; Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985), which can foster a deeper sense of group cognition and loyalty.

Mechanisms of Authoritarian Survival

In minority regimes with an excluded majority, a heightened fear of majoritarian rule can trigger three interrelated dynamics that enable the regime to survive challenges from below (see Figure 2). First, it enables the demobilization of the minority group. Members of the minority group have no incentives to challenge the regime due to the “linked fate” perception that they develop. Individuals with this perception use their group’s relative status and interest vis-à-vis the outgroup as a heuristic shortcut for their individual interests (Dawson Reference Dawson1995, 61). Consequently, the group’s collective interest takes precedence over the immediate material concerns of individual group members, leading them to acquiesce regardless of their socioeconomic status or ties to the regime. Thus, even those critical of the regime tend to withhold dissent and refrain from anti-regime mobilization, bolstering group cohesion and regime strength.

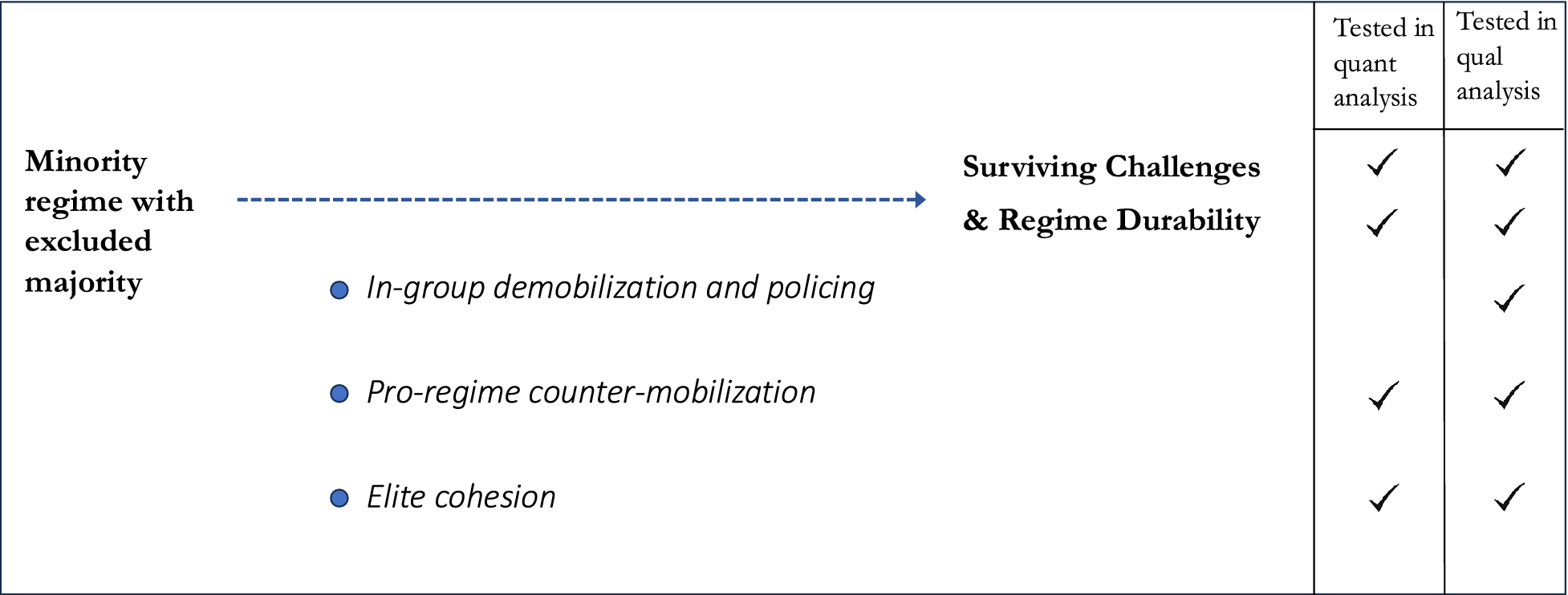

Figure 2. Mechanisms of Surviving Challenges and Durability

In-group policing and sanctions further reinforce group demobilization. This includes exerting social pressure or sanctioning group members who show critical views or engage in anti-regime activities. Existing research indicates that social pressure and community monitoring shape group formation and strength (Laitin Reference Laitin1998; Lust Reference Lust2022, 31), influence members’ behaviors during conflicts (Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin1996, 722; Mazur Reference Mazur2021, 53), foster coethnic cooperation (Cammett, Chakrabarti, and Romney Reference Cammett, Chakrabarti and Romney2023; Habyarimana et al. Reference Habyarimana, Humphreys, Posner and Weinstein2009), and affect voting choices (Jung and Long Reference Jung and Long2023). Social sanctions can also facilitate high-risk collective action and participation not only in rebellions but also in counterinsurgency mobilization (Humphreys and Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2008). In minority autocracies, in-group policing silences and prevents within-group criticism and challenges to the regime, reinforcing group solidarity and regime cohesion.

Second, heightened threat perception allows the regime to employ the minority group in counter-mobilization and repression. In highly polarized contexts, where threat perception is elevated, supporters of the incumbent are more likely to endorse repressive measures (Arbatli and Rosenberg Reference Arbatli and Rosenberg2021; Linz Reference Linz1978, 29–30) and perceive the opposition as illegitimate and threatening (Radnitz Reference Radnitz2010; Svolik Reference Svolik2020). This enables the regime to mobilize loyal civilians within the minority group, who participate in counter-rallies and even take active roles in repression by forming civilian-led militias. Such mobilization strengthens the regime’s confidence and repressive capacity, allowing it to compensate for limited resources during crises and maintain stability (Hellmeier and Weidmann Reference Hellmeier and Weidmann2020; Ong Reference Ong2022; Smyth, Sobolev, and Soboleva Reference Smyth, Sobolev and Soboleva2013).

Third, heightened threat perception among elites from the ruler’s ethnic group reinforces their loyalty to the regime. Elite defections represent the most significant threat to authoritarian rule (Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright, Wright and Frantz2018; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). During regime crises, such as popular uprisings, defections become even more likely (Acemoglu, Ticchi, and Vindigni Reference Acemoglu, Ticchi and Vindigni2010; Aksoy, Carter, and Wright Reference Aksoy, Carter and Wright2015; Greitens Reference Greitens2016). However, in minority regimes with an excluded majority, the loyalty of coethnic elites remains exceptionally strong, as they view their fate as closely tied to the regime. Unlike other autocracies, where crises typically increase the risk of elite defections, minority regimes experience the opposite: heightened threat perception during challenges strengthens elite loyalty. This allows the regime to effectively deploy its coercive institutions for unrestrained, high-intensity repression without fear of defections.

Our discussion points to a clear set of observable implications, summarized in Figure 2. The first two implications pertain to the expected outcomes. Minority regimes with an excluded majority are expected to be more durable, breaking down less frequently than other regimes. This resilience is rooted in their heightened ability to survive challenges. As a result, anti-regime challenges should be less likely to succeed compared with those against other regimes. With regard to the mechanisms underpinning authoritarian survival during such challenges, we can expect to observe (1) in-group demobilization and policing, including limited participation in anti-regime activities and sanctions within the group against dissenters; (2) increased levels of pro-regime counter-mobilization; and (3) a reduced likelihood of elite defections.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND DATA

To evaluate the theory on the survival of minority autocracies, I use a mixed-method research design, combining cross-case statistical inference with within-case causal mechanism analysis (Goertz Reference Goertz2017). Statistical analysis provides insights into mean causal effects and external validity, whereas within-case qualitative analysis explores causal mechanisms that are less amenable to statistical testing, such as fear of majoritarian rule and in-group demobilization and policing. In addition, this design also ensures that the statistical analysis is based on a model “designed, refined, and tested in light of serious qualitative analysis” (Seawright Reference Seawright2016, 8).

First, I statistically assess the theory and its causal mechanisms using datasets on authoritarian regime breakdown and anti-regime challenges. The first dataset includes all authoritarian regimes covered by the extended version of Geddes, Wright, and Frantz (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014), covering 1900–2015. I also use the NAVCO dataset, which tracks anti-regime challenges from 1945 to 2013 (Chenoweth and Shay Reference Chenoweth and Shay2019). Second, I analyze qualitative evidence from Bahrain using “theory-testing process tracing,” which entails three key components: (1) conceptualizing a causal mechanism; (2) identifying clear empirical observables for each part of the mechanism in the selected case; and (3) using case-study evidence to verify the presence of the predicted observable implications (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, 336).

The case of Bahrain was selected for several reasons. First, it is a “typical case” (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, 146; Seawright and Gerring Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) with a Sunni minority regime excluding a Shi’a majority, and has survived for over 40 years while withstanding a significant popular challenge in 2011. Second, Bahrain represents a hard case for testing the resilience of minority regimes due to the presence of a historically strong opposition, the absence of a ruling party, and the high levels of anti-regime mobilization during the uprising of 2011—factors that should theoretically make regime survival less likely. Finally, selecting a contemporary case with the ability to access the country facilitates data collection and ensures recent, accurate accounts.

For evidence, I draw on 25 interviews conducted in Bahrain, Lebanon, and London (UK) between October and December 2022. To ensure the safety and confidentiality of my interviewees, I keep their identities anonymous. In Supplementary Appendix A5, I discuss my interview procedures and ethical considerations. I also include the full list of research participants who are identified by code for reference in the text (e.g., P.1 and P.2). Additional evidence comes from Arabic- and English-language sources, including newspapers, books, and reports by local and international human rights organizations.

Data on Minority Regimes

To identify cases of minority autocracies, I started with the extended version of Geddes, Wright, and Frantz’s (GWF) (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014) dataset as presented in Casey et al. (Reference Casey, Lachapelle, Levitsky and Way2020), which lists all authoritarian regimes between 1900 and 2015. I then narrowed the cases to regimes that (1) practice ethnic recruitment in the military and security forces and (2) are led by dominant minority ethnic groups, using the Ethnic Stacking in Africa dataset (Harkness Reference Harkness2021) and the GWF dataset, which codes regimes with disproportionate ethnic representation among officers. Second, to identify dominant minority groups, I used the Ethnic Power Relation Dataset (Cederman, Wimmer, and Min Reference Cederman, Wimmer and Min2010), coding a group as a dominant minority if it constitutes less than 45% of the ethnically relevant population and is coded as Senior, Dominant, or Monopoly. Footnote 2 For regimes formed before 1946 or after 2010 (n = 81) and included only in Casey et al.’s (Reference Casey, Lachapelle, Levitsky and Way2020) extended version, I consulted secondary sources to verify if they meet the criteria for ethnic stacking and minority control (see details in Supplementary Appendix A2).

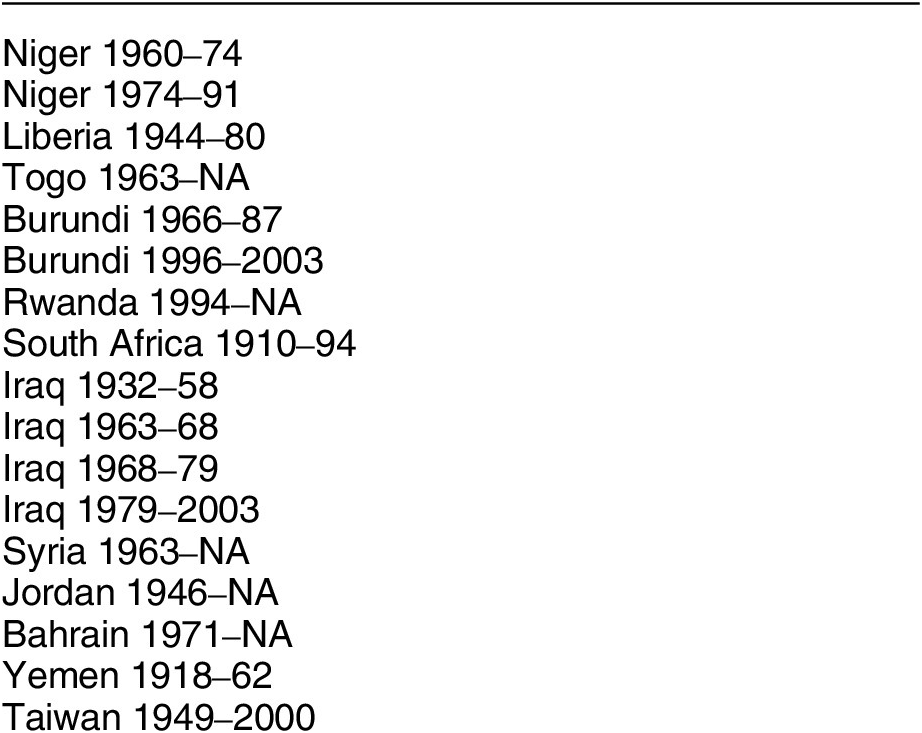

This results in the identification of all minority autocracies between 1900 and 2015 (listed in Supplementary Table A1; n = 71). From this list, I then identify cases of minority autocracies that exclude a single majority ethnic group—a relatively homogeneous ethnic group representing over 50% of the ethnically relevant population and excluded from power. These regimes are listed in Table 1, and Supplementary Appendix A3 includes a narrative account for each case.

Table 1. Minority Autocracies with Excluded Majority (1900–2015)

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

Evidence of Regime Durability

To test the relationship between minority regimes and authoritarian durability, I fit a set of logistic regressions in which the dependent variable is authoritarian regime breakdown, coded as 1 in any year an authoritarian regime loses power, and 0 otherwise. I include a range of control variables to account for country- and regime-level characteristics that are typically associated with regime durability. These controls include GDP per capita, GDP growth (Lipset Reference Lipset1959; Svolik Reference Svolik2015), population size, oil revenue (Hill and Jones Reference Hill and Jones2014; Ross Reference Ross2001), and regime type with binary variables for party-based, personalist, military, and monarchical regimes (Geddes Reference Geddes1999; Yom and Gause Reference Yom and Gause2012). I also control for foreign support, a factor shown to significantly influence regime durability (Casey Reference Casey2020). Using data from V-Dem (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg and Teorell2022), I construct a binary variable indicating whether the regime relies on a colonial or foreign state to sustain its rule.Footnote 3 Finally, I include country and year fixed effects to control for unobserved country-specific characteristics and temporal trends.

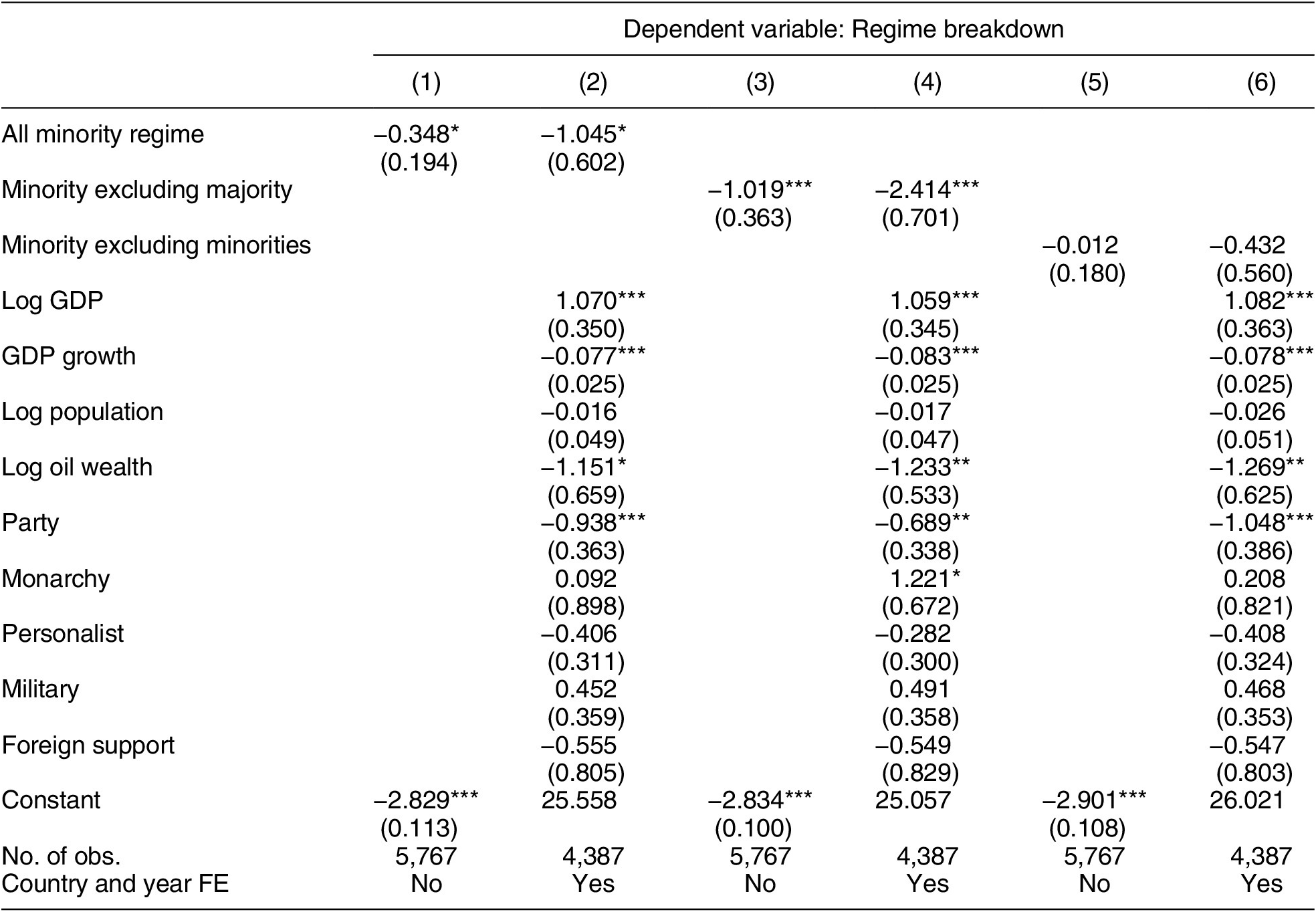

Table 2 presents the results of the logistic regression analyses. Column 1 provides a baseline specification using all minority regimes as the independent variable, and column 2 adds the control variables. The results indicate that minority regimes are associated with a statistically significant reduction in the likelihood of regime breakdown compared to nonminority regimes. I then disaggregate minority regimes into the two distinct types identified in my theory: those that exclude a majority (columns 3 and 4) and those that exclude other minorities (columns 5 and 6). Consistent with my hypothesis, the estimated coefficient for minority regimes excluding a majority is negative and very significant. Specifically, I find that the probability of breakdown for minority regimes with an excluded majority is almost three times lower than that of other authoritarian regimes (2.1% vs. 5.6%).Footnote 4 In contrast, the effect for minority regimes that exclude other minorities ceases to be statistically significant (columns 5 and 6).

Table 2. Authoritarian Regimes Breakdown (1900–2015)

Note: Standard errors are clustered by country. *p

![]() $ < $

0.1, **p

$ < $

0.1, **p

![]() $ < $

0.05, ***p

$ < $

0.05, ***p

![]() $ < $

0.01.

$ < $

0.01.

These results provide support for the idea that the durability of certain minority regimes in countries like Bahrain, Syria, and Apartheid South Africa is not the result of their ethnic diversity or minority character, but rather their unique ethno-political configuration where an ethnic minority group dominates over a single excluded majority group.

I conduct several robustness checks, presented in Supplementary Appendix A4. First, I replicate the analysis using the GWF dataset covering 1946–2010 to check the consistency of results across different time periods. Second, to assess the sensitivity of the results to different coding and operationalizations of authoritarian regimes and their spell, I replicate the analysis using the Autocracies of the World dataset (Magaloni, Chu, and Min Reference Magaloni, Jonathan and Eric2013). Notably, the coding choices in this dataset differ in ways that should bias the results against my hypothesis. Specifically, it splits several minority regimes with excluded majority into two different regimes, increasing the count of regime breakdowns within the treated group.Footnote 5 All these tests yield results that are consistent with my theory, indicating robustness to different time coverage, regime operationalization, and dataset choices.

Finally, to address potential issues arising from the small number of minority regimes with excluded majority, I employ a data preprocessing method, specifically coarsened exact matching, which prunes observations so that the remaining data have better balance between the treated and control groups, thereby reducing model dependency and statistical bias (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Imai, King and Stuart2007; Iacus, King, and Porro Reference Iacus, King and Porro2012). I selected covariates potentially relevant to the emergence and persistence of minority regimes. I control for colonial legacy and support, including whether the country gained independence through decolonization and whether the regime relies on a colonial power or foreign state to maintain its rule. I also control for civil war, which can alter ethnic domination (Cederman, Gleditsch, and Buhaug Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Buhaug2013). Finally, I control for certain regime and country characteristics by including three binary variables indicating the type of the previous regime (party, personalist, and monarchy) as well as GDP per capita and population size.Footnote 6

The propensity score was estimated using a logit regression of the treatment on the covariates, and Amelia routine was performed to handle missing data with 20 imputations. Figure A.1 in Supplementary Appendix A4 presents measures of covariate balance before and after matching, showing that all standardized mean differences for the covariates are less than 0.1. Using a weighted logistic regression in the matched sample, I find that the average effect of minority regime in the treated group is −1.22 (p < 0.001), which corresponds to a 4.2 percentage point reduction in the probability of breakdown.Footnote 7 Finally, to address concerns about statistical power, given the small number of minority regimes, I conduct a design analysis following Gelman and Carlin (Reference Gelman and Carlin2014) to estimate the probability of a Type S error (Sign) and a Type M error (Magnitude). The analysis shows a negligible chance of misidentifying the effect’s direction and a 7.9% exaggeration factor, suggesting that the results are fairly accurate in magnitude (see details in Supplementary Appendix A4).

While it is impossible to eliminate entirely the possibility of unobserved confounders, a limitation inherent to all observational studies, the matching technique strengthens the confidence in treating minority regimes as exogenous to regime survival. Moreover, testing for other observable implications and the causal mechanisms in the subsequent sections provides additional assurance that my results are not driven by unobserved factors predisposing certain regimes to minority rule.

Quantitative Examination of Mechanisms

To assess the resilience of minority autocracies with an excluded majority against anti-regime challenges and the mechanisms underpinning this resilience (illustrated in Figure 2), I employ the NAVCO 2.1 dataset, which lists all violent and nonviolent anti-regime challenges from 1945 to 2013 (Chenoweth and Shay Reference Chenoweth and Shay2019). I narrow this sample to only include observations within authoritarian regimes and coded challenges to minority regimes with the excluded majority, using a binary variable. The statistical analysis involves three dependent variables. First, Challenge Success is a binary indicator of whether the challenge was successful, as coded by NAVCO. Second, Elite Defections is a binary variable from NAVCO that takes the value of 1 if the regime experienced major defections or loyalty shifts during the challenge, and 0 otherwise. Third, Mobilization for Autocracy is a continuous variable from the V-Dem dataset that captures the frequency and scale of mass mobilization events explicitly organized in support of authoritarian regimes, where a higher score indicates greater levels of mobilization. This measure aligns with my theoretical conceptualization of pro-regime counter-mobilization.

I control for a set of covariates associated with challenge success, drawing on Stephan and Chenoweth (Reference Stephan and Chenoweth2008). This includes GDP per capita, population size, the size of the challenge, challengers’ use of violence, external support to the regime, external support to the challenge, and challenge duration (in days). I also add a control for opposition unity, which has been associated with more successful mobilization (Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2011; Howard and Roessler Reference Howard and Roessler2006). Finally, I include country and year fixed effects. All variables except GDP and population are sourced from the NAVCO 2.1 dataset.

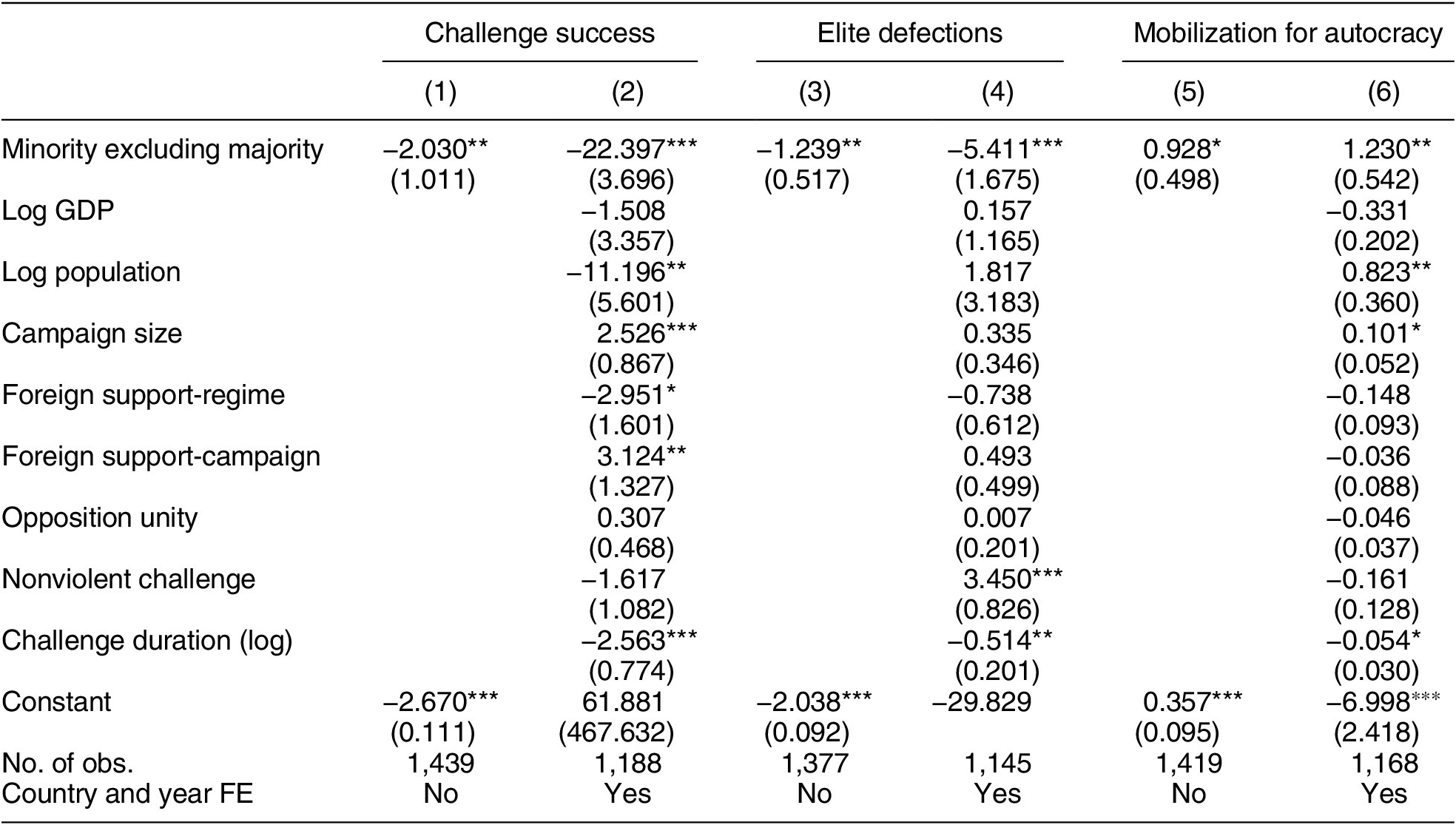

Table 3 presents the results from a set of regression models. Models 1 and 2 and models 3 and 4 use logistic regression, as their outcome variables—challenge success and elite defections, respectively—are binary. Models 5 and 6, on the other hand, employ an OLS regression because the outcome variable, mobilization for autocracy, is continuous. Consistent with my theoretical expectations, the estimated coefficient for minority regimes with an excluded majority in both the baseline model (column 1) and the model with controls (column 2) is negative and highly significant, suggesting that challenges against such regimes are less likely to be successful compared with challenges in other authoritarian environments. Specifically, the likelihood of success for challenges against minority regimes with an excluded majority is more than seven times lower compared with challenges against other authoritarian regimes (0.9% vs. 6.5%). In Supplementary Table A7, I show that the results are also robust to using Beissinger’s (Reference Beissinger2022) Revolutionary Episodes dataset, indicating that they are not sensitive to alternative operationalization and coding rules.

Table 3. Challenges to Authoritarian Regimes (1945–2013)

Note: Standard errors are clustered by country. *p

![]() $ < $

0.1, **p

$ < $

0.1, **p

![]() $ < $

0.05, ***p

$ < $

0.05, ***p

![]() $ < $

0.01.

$ < $

0.01.

Models 3 and 4 assess the effect on elite defections during challenges. They show that minority regimes with an excluded majority are significantly less likely to experience major elite defections. Specifically, the probability of elite defections against such regimes is more than three times lower compared with defections during challenges to other regimes (3.6% vs. 11.5%). Finally, models 5 and 6 use “mobilization for autocracy” as the dependent variable and indicate that challenges against minority regimes with an excluded majority are associated with significantly higher levels of mobilization for autocracy during such challenges.

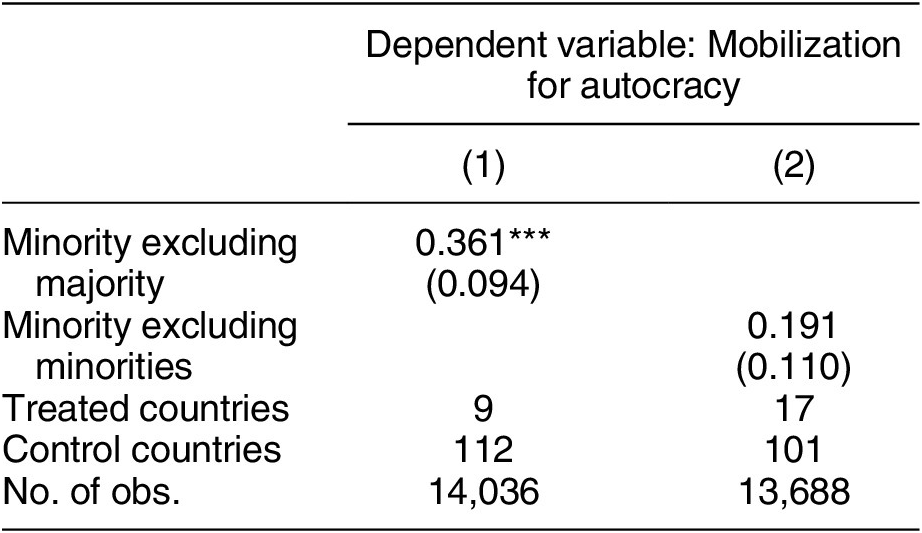

If the theory of minority fear of majoritarian rule is true, we should also expect to observe higher levels of mobilization for autocracy not only during times of anti-regime challenges, as we show above, but also in response to the onset of minority rule that excludes a single majority. To test this proposition, I employ the generalized synthetic control (GSC) method (Xu Reference Xu2017), which is also useful in addressing concerns related to the small number of minority regimes with the excluded majority.Footnote 8

The synthetic control method approximates a quasi-experimental research design, in which treated cases (minority regimes) are compared to a synthetic control group constructed from a “donor pool”—a group of untreated cases. This ensures a close pretreatment match between the treated and control groups. Consequently, any substantive effect of the treatment should become evident only after the treatment occurs (Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2010). GSC extends the traditional synthetic control method by allowing for the incorporation of multiple treated units with different treatment timings within the same model.Footnote 9 I selected predictor variables that potentially affect mobilization for autocracy, which can improve the GSC matching of treatment and control groups. This includes (1) GDP per capita, (2) population, (3) the regime promotes socialist or communist ideology, (4) the regime promotes religious ideology, and (5) a measure of physical violence, all sourced from the V-dem dataset. These variables were selected based on (1) a preliminary analysis that showed them to be strong predictors of mobilization for autocracy and (2) their extensive coverage over a long period of time to ensure a sufficient pretreatment period for most countries with minority regimes. I chose a 12-year pretreatment period before regime birth.Footnote 10

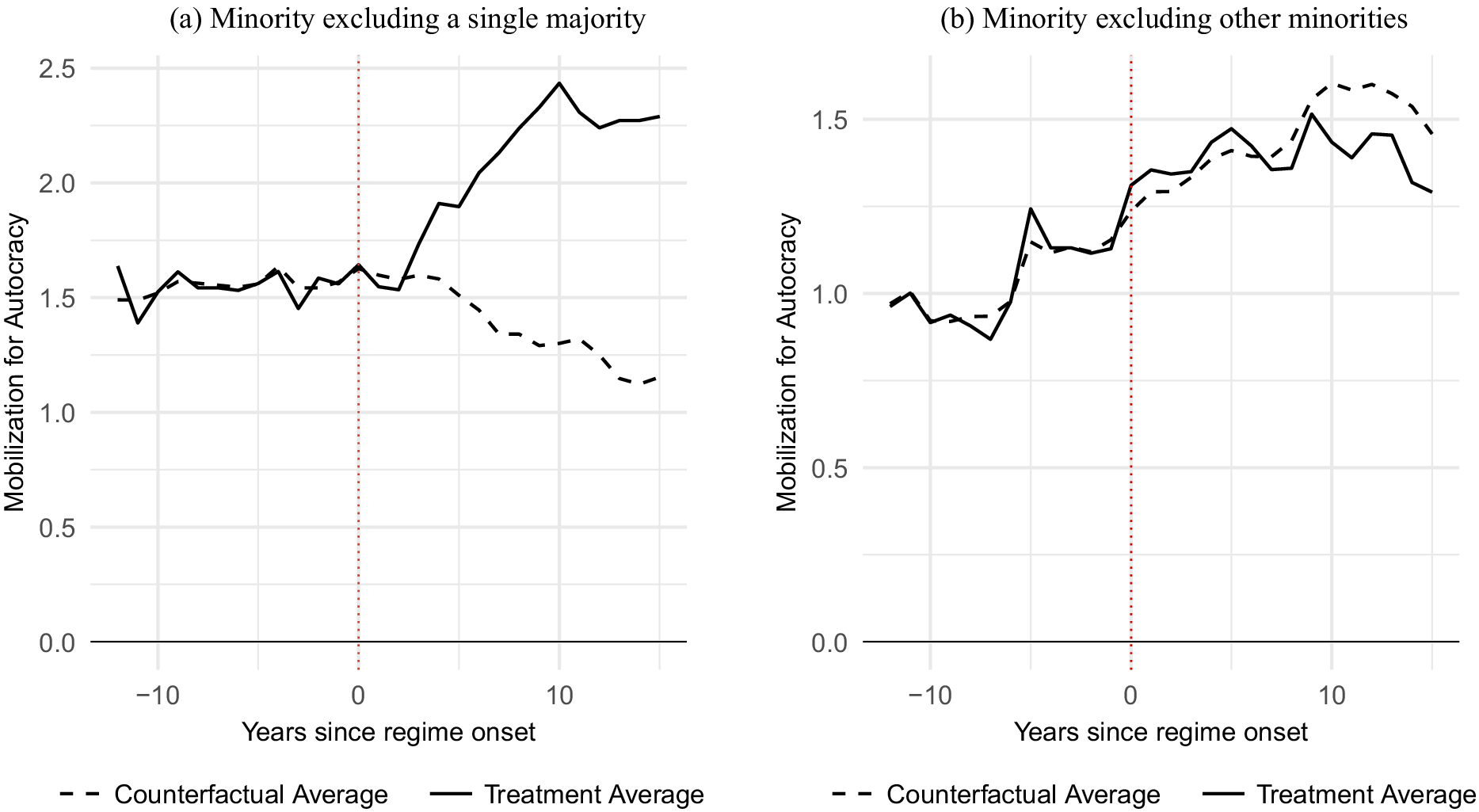

Figure 3 plots the average observed values of the mobilization for autocracy measure before and after the treatment alongside the counterfactual trajectory from the synthetic analysis for the two types of minority regimes. The measure ranges from 0 (no mobilization) to 4 (very high, large-scale mobilization). As shown, the synthetic group closely tracks the mobilization for autocracy values for the actual minority regimes group during the pretreatment period, indicating that the synthetic group approximates the counterfactual scenario of other regimes’ onset. The patterns align well with the hypotheses. Only minority regimes with an excluded majority experience a significant increase in mobilization for autocracy (panel a). In contrast, panel b shows that minority regimes with excluded minorities have a statistically insignificant effect, indicating that the minority character is not sufficient for authoritarian mobilization. Table 4 presents the estimated average treatment effects over a posttreatment period of 15 years for the dependent variable (mobilization for autocracy) for the two types of minority regimes.

Figure 3. Effect of Minority Regime Onset on Mobilization for Autocracy

Table 4. The Average Treatment Effect on the Treated of Minority Regimes on Mobilization for Autocracy (GSC Models)

Note: Standard errors are estimated through one thousand bootstrap iterations. The models include interactive fixed effects and time-varying covariates. *p

![]() $ < $

0.1, **p

$ < $

0.1, **p

![]() $ < $

0.05, ***p

$ < $

0.05, ***p

![]() $ < $

0.01.

$ < $

0.01.

Overall, the quantitative analyses provide evidence consistent with the hypotheses. Minority regimes with the excluded majority are more durable, and they display a significantly higher level of elite loyalty and pro-regime counter-mobilization. To further evaluate these and other causal processes, especially the fear of majoritarian rule and in-group dynamics, I turn to qualitative evidence on the survival of the regime in Bahrain during the 2011 uprising.

QUALITATIVE EVIDENCE FROM BAHRAIN

Bahrain has been ruled by the Sunni Al Khalifa royal family since 1783, after they seized the island from Zubarah (in present-day Qatar). In 1861, Bahrain became a British protectorate under a treaty that recognized the Al Khalifa as the ruling tribe while allowing Britain to exert control over most aspects of governance. The British colonial administration relied on elites from the Sunni minority, whom they regarded as more loyal, in managing and controlling the Shiite-majority population. Consequently, members of the Sunni minority were disproportionately recruited into emerging state institutions, especially in defense and security sectors (AlShehabi Reference AlShehabi2019; Khalaf Reference Khalaf2004; Rumaihi Reference Rumaihi1995). After gaining independence in 1971, the Sunni minority, which constitutes approximately 30% of the population, maintained a dominant presence within state institutions. This control is reflected in the persistent exclusion of the Shiite majority from senior government positions, especially within the coercive apparatuses, such as the police, army, and secret intelligence, which are exclusively Sunni (International Crisis Group 2011, 4–5).

Observable Implications

I begin my process tracing from the uprising of 2011. Per the mechanisms outlined in Figure 2, regime survival in Bahrain should come from mass and elite fear within the minority group of a majoritarian rule. One observable implication of this mechanism is that average Sunnis and elites should widely express fear regarding potential political change and the imposition of majoritarian rule, both in private interviews and the public record. Opposition tactics and rhetoric that acknowledge this fear and attempt to address or counteract it would provide further support. If the posited mechanisms are operating, this fear should translate into the following three implications, as outlined in Figure 2. First, we should observe nonparticipation across all subgroups of Bahraini Sunnis; if this loyalty is driven by the fear of majoritarian rule rather than by material benefits, we should see no variation based on connections to the regime and socioeconomic background. We should also observe evidence of in-group policing, where average Sunnis sanction or physically harm their relatives and neighbors who lean toward the uprising or criticize the regime. Second, we should find evidence of significant pro-regime counter-mobilization efforts, which might include organizing rallies, conducting spying and reporting campaigns, and forming civilian militias that engage in repression. Third, at the elite level, we should observe strong cohesion among the regime’s elites, no defections, and a willingness to obey orders and employ repression against peaceful protesters.

The 2011 Popular Uprising

The 2011 Bahraini protests presented a significant challenge to the regime. Demonstrators from largely Shiite towns took to the streets to demand greater political and social rights. Hundreds of thousands participated not only at the major focal point, the Pearl Roundabout, but also in numerous Shiite towns and villages across the country. This turnout, with an estimated one in four citizens participating, was deemed one of the largest demonstrations in history, far exceeding Charles Kurzman’s assertion that revolutions rarely involve more than 1% of the population (Yom Reference Yom2014, 52).

Fear of Majoritarian Rule

With their disproportionate presence in state institutions, the Sunni minority has consistently exhibited a deep fear of a potential shift in ethnic power dynamics. Its members largely believe that any substantial political reform would threaten their privileged position. This concern is underpinned by their minority status, fostering a perception that they would be overwhelmed by the Shiite majority.Footnote 11 Such fear “permeates the government as well as the island’s Sunni community” (International Crisis Group 2005, 12). While the regime does not officially promulgate these fears of loss and subordination, loyalist Sunni parties and informal networks within the Sunni community widely circulate them.Footnote 12

The Sunni minority largely perceived the uprising as a “Shiite revolt,” accusing it of harboring narrow sectarian demands, albeit “hidden behind its national rhetoric.”Footnote 13 Informal conversations and rumors within the Sunni community propagated a narrative that depicted the protests as violent and primarily targeting the Sunni minority, with an underlying intention to overturn the current ethno-political power balance. State media amplified this fear and warned against what they described as “sectarian” protests.

Recognizing that Sunni loyalty to the regime is rooted in the country’s ethnic-power dynamics, the Shiite opposition employed various strategies to mitigate the minority group’s fear. First, they consistently emphasized a unifying national rhetoric, chanting “not Sunni, not Shia, National Unity!” (Matthiesen Reference Matthiesen2013; Shehabi and Jones Reference Shehabi and Jones2015). Second, most factions of the traditional opposition in Bahrain maintained moderate demands, abandoning the idea of a full majoritarian democracy and advocating instead for political participation within a constitutional monarchy (Murshid Reference Murshid2014). As one opposition leader explained, demands for a democratic republic are seen as “too radical” in the context of Bahrain.Footnote 14 Another Shiite opposition leader noted: “While we represent 70 per cent of the island, we only want an equal partnership with the regime” (International Crisis Group 2005, 16–7). The opposition has also emphasized political dialogue and nonviolent means of political change to foster trust with the Sunni minority. Shiite religious leaders utilized their Friday sermons to emphasize the importance of political moderation (International Crisis Group 2005, 16–7).

In-Group Demobilization and Policing

Despite their efforts, the opposition struggled to find enough allies within the Sunni minority, which seemed united behind the regime. Sunni individuals, regardless of their socioeconomic status or ties to the regime, generally abstained from protests and opposed them.Footnote 15 Several interviewees recounted that their neighbors or friends who had struggled financially and criticized the regime’s policies before the uprising became staunch supporters. Additionally, several independent Sunni political parties and figures, such as Al-Asalah, Al-Menbar, and the National Charter Association, while presenting themselves as reform movements, acted as “Sunni loyalists,” avoiding criticism of the regime and calling for increased repression against challengers.Footnote 16 As one interlocutor noted: “Some of them claim to be opposition, but they oppose the opposition more than they oppose the regime.”Footnote 17 Another described them as “more royalist than the king.”Footnote 18

While many of these Sunni forces are co-opted by the regime, this does not fully explain their firm loyalty. The regime often restricts their activities by cutting funds, benefits, and even barring their candidates from parliamentary elections, as seen in the 2022 elections (Bahrain Mirror 2022). As one interviewee explained: “Yes, many of these parties and figures benefit from the regime… but their loyalty is primarily driven by their mistrust of political change… democracy in their minds would certainly lead to Shiite domination and Sunni marginalization.”Footnote 19

This led to growing frustration and divisions among the opposition. One interviewee described: “Every time we take a political step, be it peaceful protest, political coalition, or a political statement, we are expected to ‘reassure Sunnis’… are we really not doing enough to get them on our side? Or are we giving up our right to a full democracy for the illusion of persuading them to abandon the regime?” While certain opposition parties and figures have considered “reassuring Sunnis” essential for any chance of success, others viewed this effort as “futile… [because] the Sunni sect is fully captured by the regime… offering it unconditional loyalty.”Footnote 20 Another explained: “We initially hoped to attract support from the Sunni community. But, as their loyalty to the regime appeared unconditional, a sense of despair grew within our ranks about the chances of altering their stance.”Footnote 21

The limited number of ordinary Sunni individuals and activists who took part in the protest activities faced backlash from their own Sunni community. They were seen as rogue members violating the group’s established stance and thus deserving of group sanctions. Many interviewees recounted incidents of extreme pressure by Sunni families on their own members, aimed not only at discouraging their participation in anti-regime protests but also at preventing them from voicing any public criticism against the regime and its repression. In addition to intimidation, sanctions included social ostracization, with disobedient individuals facing boycotts and even being barred from entering their own neighborhoods. “The psychological and emotional toll was considerable,” one activist from a Sunni background shared with me. He explained: “I became estranged from my family after the uprising because of my stance against the regime… they refused to talk and listen to me… several family relatives called me a traitor.”Footnote 22 Others endured additional punitive actions, including finding garbage and waste deliberately left in their backyards and at their entrances, allegedly done by their loyalist neighbors.Footnote 23 One opposition leader from a Sunni background told me: “Certainly, the Shiite community bears the brunt of the regime’s repression. But we, as Sunni opposition members, have experienced repression and exclusion not only from the regime but also from our own community… the cost of opposition and voicing dissent is extremely high for us, forcing many to remain silent.”Footnote 24

Counter-Mobilization

Heightened threat perception triggered group solidarity and counter-mobilization. On February 21, pro-regime counterprotests started at the Sunni al-Fatih mosque in Manama under the banner of the National Unity Gathering. The new gathering was led by Abdul-Latif al-Mahmood, a former Sunni opposition and reformer who shifted to support the regime following the uprising. This countermovement attracted tens of thousands of ordinary Sunnis, activists, and politicians. Among these participants were Sunni members of associational groups, such as labor unions, who defected and closed ranks with their Sunni community after their association openly supported a democratic republic.

In its inaugural political statement, the al-Fatih Sunni gathering emphasized demands for reforms, national unity, and the citizens’ right to freedom of expression. It attempted to present itself as an independent societal and political force, making parallel and equally legitimate claims on the regime, while firmly opposing any demands for constitutional amendments that might alter the existing ethno-political balance of power.

The al-Fatih movement took a more extreme stance against the uprising soon after. Their leader, Abdul-Latif al-Mahmood, addressed a large gathering of Sunni loyalists: “They want to humiliate the Sunni community. Their intention is the domination of one sect over another, just as happened in Iraq” (Murshid Reference Murshid2014, 204). Another speaker, Mohamad Khaled, addressed tens of thousands and declared that the Sunni minority will fight back no matter the costs: “Our meat is tough, and we have no fear.” He called for the formation of popular defense committees, warning that “the enemy is stalking the prey. Do you wait until our dignity is violated and we are driven out of our homes?” He also encouraged regime violence against peaceful protesters at the Roundabout, the focal point of the uprising: “They claim to be peaceful but numerous weapons were discovered there. They are disrupting normal life and people’s interests. How long should we tolerate this?” (Murshid Reference Murshid2014, 223).

The loyalist counter-mobilization not only justified and called for a crackdown against the protests but also actively participated in repression. With the expansion of anti-regime protests, the Sunni pro-regime movement became a crucial force to counter this growing opposition. Newly established pro-regime vigilantes and militias, primarily composed of civilians, played an increasingly important role in repression. They attacked demonstrations in the streets and at universities, wielding knives, sticks, and stones. In addition, these pro-regime militias proliferated within and outside residential Sunni areas, identifying themselves as “popular committees” or “local security.” They set up checkpoints outside their towns to block the protests and intimidated and attacked individuals passing through from Shiite towns. They also targeted the offices of opposition parties and the independent Bahraini newspaper, Al-Wasat, known for its critical stance toward the regime.Footnote 25

Sunni loyalists took on an additional important role in suppressing dissent. In workplaces and within their neighborhoods, they closely monitored, reported, and intimidated their colleagues and neighbors who seemed to back or empathize with the protesters’ demands. One interviewee recounted being reported to the security by his colleague: “We had worked together as teachers in a public school for ten years… had family gatherings… and yet, he didn’t hesitate betraying and harming me.”Footnote 26 Loyalists also used social media to identify and report protesters to security forces, helping to target them for arrest. They posted photos from demonstrations, highlighting specific participants by circling their faces and naming them.Footnote 27 Thousands of people were imprisoned, lost their jobs, or were demoted because of such reports, which created a climate of fear and silenced dissent.

Most of the loyalists taking on this counter-mobilization role were ordinary Sunni civilians, and most of them with no direct ties to the security forces. They “volunteered and willingly took on this responsibility,” as described by one interviewee.Footnote 28 Another witness of a pro-regime gathering outside a Sunni neighborhood described the scene: “I looked at their faces in shock and couldn’t believe what I was seeing… our neighbors and ordinary young people who I often see going to school and university in neat clothes. But today they carried sticks and swords that seemed larger than their ages.”Footnote 29

Beyond their role in direct and indirect repression, the Sunni counter-mobilization also sent signals of regime strength, allowing it to intensify repression. They created a “loyalist street” as a counterweight to the “opposition street” with “ordinary civilians and legitimate demands on both sides.” According to several interlocutors, the show of support from the minority group bolstered the confidence of the regime’s elites, especially its coercive institutions, which became essential in the decisive moment when the regime decided to crush the uprising with full force.Footnote 30 Abdul-Latif al-Mahmood, the leader of the al-Fatih Sunni counter-movement, would later pay homage to the loyal Sunni community and its counter-mobilization efforts, which “fostered a sense of strength in times of weakness and a sense of unity in times of divisions” (Rashad Reference Rashad2014).

Elite Loyalty and Repression

Unlike the regimes in Egypt and Tunisia, which failed to deploy their militaries against protesters, the Bahraini regime effectively used its military in repression. Elite defections came almost exclusively from individuals of Shiite background, while Sunni state elites and officers remained loyal. In each encounter, the military fired upon the protesters. The army also spearheaded the major crackdown that cleared the Roundabout, resulting in the deaths and injuries of hundreds of demonstrators. The intensification of repression was not only welcomed by the Sunni minority group but was also deemed long overdue. Many within the minority group criticized the regime for not using its iron fist early enough and for allowing the protests at the Roundabout to go on for weeks.Footnote 31

In summary, this brief case study has elucidated the mechanisms by which the regime has maintained considerable durability and survived the 2011 uprising. Specifically, the resilience of the Bahraini regime is rooted in the largely unconditional loyalty of its Sunni minority group due to a perceived threat of Shiite-majority rule. The Sunni community viewed the uprising of 2011 as a Shiite-driven revolt that will permanently shift the ethno-political power dynamics, relegating them to a marginalized status. This perception fostered exceptional group unity and loyalty, resulting in counter-mobilization and the successful deployment of the military in suppressing the uprising.

Alternative Explanations

While Bahrain’s colonial legacy and foreign support may have played a role in the regime’s survival, a closer examination highlights the limitations of these arguments. One concern is that a potential persistence of foreign sponsorship by the colonizer may contribute to regime survival. However, after independence, Britain’s influence diminished and was replaced by stronger ties with the United States. In addition, during the 2011 uprising, the United States criticized the regime’s repression and pressured it to halt the crackdown and engage in negotiations with the opposition to implement meaningful reforms (Ottaway Reference Ottaway2011). Indeed, linkages to the West can be double-edged; rather than merely supporting autocratic policies, they can also increase pressure for liberalization (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2005).

Second, the Saudi intervention in March 2011 is often cited as an alternative explanation for the survival of the Bahraini regime (Kamrava Reference Kamrava2012). However, this intervention is less helpful in explaining why the regime was able to withstand the popular challenge for several reasons. First, large-scale mobilization continued for almost 3 years after the regime crushed the focal point of the uprising and after Saudi troops left the country. These events occurred between 2011 and 2013, with weekly protests in Shiite towns and occasional large-scale gatherings in the capital, Manama. In fact, the largest anti-regime demonstration in Bahrain’s history took place in March 2012 (BBC News 2012), 1 year after the Saudi troops left. Despite this continued unrest, the regime remained cohesive until the protests eventually abated. Second, in my interviews with Bahraini participants, almost no one attributed the regime’s survival to Saudi Arabia. There was significant agreement that the Bahraini military alone was capable of quelling the uprising and that internal dynamics and counter-mobilization were more crucial for regime survival. Finally, and more broadly, many autocrats in the region received support from regional powers during the Arab Spring of 2011 (e.g., Egypt, Yemen, and Tunisia), yet they collapsed in the face of even smaller and shorter uprisings and mobilization. In short, foreign sponsorship alone is insufficient without regime cohesion, which distinguished the two minority regimes in Syria and Bahrain during the Arab Spring.

CONCLUSION

Contrary to the view that ethnically dominated regimes are susceptible to breakdown, my findings show that minority regimes that exclude a single majority ethnic group exhibit exceptional durability. This resilience is rooted in their ethno-political configuration, which allows them to foster a largely unconditional loyalty due to the ruling minority’s fear of being subjected to majoritarian rule. Through statistical analyses and a detailed case study of Bahrain, we found that these regimes can foster in-group demobilization and policing, pro-regime countermobilization, and elite cohesion, enabling them to survive outsider anti-regime challenges.

Beyond the case study of Bahrain, similar dynamics of steadfast ethnic loyalty among minority groups confronting a single majority can be observed across various other contexts. These include the Hashemite regime in Jordan, sustained by its East Jordanian tribal base (Axelrod Reference Axelrod1978; Ryan Reference Ryan2011); the Alawite-dominated Assad regime in Syria (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith and Rowe2018); the Tutsi-led regime in Burundi and Apartheid South Africa’s white minority rule (Horrell Reference Horrell1970); Togo’s Kabyè-controlled regime (Buchbinder Reference Buchbinder2017); Saddam Hussein’s Sunni-dominated regime in Iraq (Haddad Reference Haddad2014); Niger’s regimes led by the Djerma-Songhai ethnic group (Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim1994); Rwanda’s RPF regime under the minority Tutsi (Reyntjens Reference Reyntjens2004); TWP’s minority rule by the Americo-Liberians (Ballah and Abrokwaa Reference Ballah and Abrokwaa2003); and Taiwan’s Kuomintang (KMT) regime dominated by Mainland Chinese (Dickson Reference Dickson and Tien2016). These minority regimes demonstrate similar mechanisms of maintaining power through ethnic group loyalty and cohesion.

The study highlights several promising directions for future research. Although scholarship on ethnic stacking in the authoritarianism literature has recently expanded, it has often inferred ethnic loyalty from ethnic identity, thus treating it as fixed. I hope that his article will stimulate more critical examination of ethnic stacking, its varying effectiveness on regime survival, and a broader understanding of when ethnic identity may be central or peripheral in different contexts. Second, this study does not examine why minority autocracies emerge in the first place. Instead, it focuses on the endogenous dynamics that unfold once these regimes are established. Future research could investigate the origins of these regimes, especially considering the impact of colonial legacies. Although this study considers factors related to these legacies, such as foreign sponsorship, they deserve a more comprehensive exploration in future studies.

Future research can also explore the conditions that can facilitate political change in minority regimes, despite the heightened fear of an excluded majority. Existing accounts of political transition in ethnically diverse societies often emphasize certain factors like social classes and civil society (Heilbrunn Reference Heilbrunn1993; Lemarchand Reference Lemarchand1994; Wood Reference Wood2000), while overlooking the influence of other identity groups defined by ascriptive characteristics and their perceptions of regime change and democratization (Clarke Reference Clarke2017). Should the conclusions of this study hold true, it becomes critical to investigate which factors and policies can influence regime transition through shaping the threat perceptions of ruling minorities. For instance, perhaps high state capacity and institutional development might lead ruling elites to seek strategic solutions for their minority status and negotiate with ethnic rivals to find institutional accommodations. Political and economic changes, whether gradual or driven by deliberate policies, could also alter perceptions of “groupness,” potentially reducing the perceived threat if the majority group came to be seen as less cohesive due to internal divisions. The KMT regime in Taiwan illustrates this dynamic. After decades of excluding the majority Taiwanese, it undertook steps that facilitated democratization, including building informal inter-ethnic alliances and recognizing religious associations, which contributed to fragmentation within the ethnic majority (Bertrand and Haklai Reference Bertrand, Haklai, Bertrand and Haklai2013; Laliberte Reference Laliberte, Bertrand and Haklai2013). These dynamics highlight the need for further research.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055425000218.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/O2MS5I.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Lucan Way, Killian Clarke, Kevin Mazur, Olga Chyzh, Janine Clark, Daniel Tavana, Ellen Lust, Daniel Mattingly, and Bryn Rosenfeld for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. I would also like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive critiques.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by Canada’s Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), the School of Graduate Studies, and the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author declares that the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board (REB) at the University of Toronto (Protocol No. 42993). The author affirms that this article adheres to the principles concerning research with human participants laid out in APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research (2020).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.