Given global trends in international mobility, many countries are now host to significant populations of immigrant origin. A core political challenge in these societies concerns the incorporation of new arrivals into the national mainstream. Seminal work in political science, sociology, and economics argues that military service is critical for constructing national identity and fostering immigrants’ integration (Janowitz Reference Janowitz1976; Posen Reference Posen1993; Weber Reference Weber1976). Reflecting this view of military service, US President Theodore Roosevelt advocated military training as a means of “Americanizing” new immigrants (Krebs Reference Krebs2006, 1). Today, states as diverse as Singapore and Morocco recently introduced national military service as a means of binding their nations together (North Africa Post 2018; Ostwald Reference Ostwald, Ho and Ong-Webb2018).

These aspirations resonate with several strands of scholarship linking military service to immigrants’ incorporation. Weber (Reference Weber1976) famously argued that militaries act as “schools for the nation” by inculcating a sense of patriotism amongst service members. Other work posits that service can integrate peripheral groups by fostering contact between “natives” and immigrants (Finseraas and Kotsadam Reference Finseraas and Kotsadam2017; Finseraas et al. Reference Finseraas, Hanson, Johnsen, Kotsadam and Torsvik2019; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2017). Additionally, military service can facilitate access to citizenship and formal educational training,Footnote 1 thereby shaping immigrants’ integration trajectories (Hainmueller, Hangartner, and Pietrantuono Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Pietrantuono2017). Further, by reducing legal and socioeconomic differences between newcomers and the established population, these measures may also increase the degree to which immigrants are accepted within the mainstream (Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015).

A major challenge bedeviling the study of military service and immigrant incorporation is the problem of self-selection—namely, immigrants who are better integrated may be more likely to join the military in the first place. Feelings of patriotism, pride in their adopted country, or a desire to prove themselves as members of the nation may lead immigrants and minorities to serve (Burk Reference Burk1995; Rosales Reference Rosales2017). Indeed, some marginalized groups have embraced military service on the grounds that service can be used to claim the rights of citizenship (Koehler-Derrick and Lee Reference Koehler-Derrick and Lee2023; Krebs Reference Krebs2006; Salyer Reference Salyer2004). For these reasons, the correlation between military service and integration outcomes is likely to be biased.

We address the self-selection problem by examining the effects of military conscription during the Vietnam War. Conscription during the years 1970–72 was decided on the basis of national draft lotteries that assigned draft numbers based on an individual’s day, month, and year of birth. This randomization into military service mitigates the self-selection problem and allows us to estimate the causal effect of military service on integration outcomes.Footnote 2

We link lottery numbers to first-generation immigrant men who appear in the 2000 long-form decennial census, the first census to report exact dates of birth (Bureau of the Census 2000).Footnote 3 We consider multiple facets of integration including naturalization decisions, residential choices, English usage, and marriage patterns. These outcomes, observed some thirty years after the Vietnam War, allow us to assess the long-term effects of military service on integration outcomes.

Overall, we find little support for the integrationist view of military service. While service itself strongly and positively predicts outcomes in our regression models that do not account for self-selection, these results disappear completely once we instrument using draft risk. Instead, our two-stage-least-squares (2SLS) models produce negatively signed, statistically insignificant coefficients. Our findings are similar when comparing immigrants from Western versus non-Western countries. Taken together, our evidence suggests that—at least for the Vietnam era—the link between military service and immigrants’ integration is largely driven by self-selection.

MILITARY SERVICE AND IMMIGRANT INTEGRATION

The question of how to integrate peripheral groups into the national core is not a new challenge. In fact, immigrant and minority integration represents just one face of a larger question confronting state- and nation-builders alike: how can unity be created from diversity?

An important means through which states have attempted to engineer political community is (mandatory) military service. A canonical example comes from the case of France during the Revolutionary and Third Republic eras. The Jacobins saw the new Revolutionary army as a melting pot in which regionalisms would give way to a French identity. As Jean-Paul Bertaud observed in his history of the Revolutionary Army, “the Jacobins tirelessly taught men from Alsace, the Auvergne, and the Midi that they were all sons of the same country. The army was the instrument of national unity par excellence” (Bertaud Reference Bertaud1988, 170). The army of the Third Republic continued this work through ceremonies that displayed and celebrated national symbols and by spreading the French language among soldiers who had previously spoken only “dialect” (Weber Reference Weber1976, 298–9).

Other European states also saw military service as a vehicle for knitting together diverse groups into a single national community. In the wake of the Napoleonic threat to the United Kingdom, British authorities formed militias to defend the homeland. They sought to ensure that volunteers “were brought into contact with wider loyalties than attachment to just one village, or just one county, or even to just one of the three component parts of Great Britain… every volunteer was invited by wartime propaganda to see himself as a guardian of British freedoms and to think in terms of Britain as a whole” (Colley Reference Colley1992, 320). In tsarist Russia, the introduction of universal conscription in 1874 was meant to increase both military capability and social solidarity along lines of civic inclusiveness (Sanborn Reference Sanborn2003, 65). Dmitry Milyutin, the Minister of War under Tsar Alexander II, advocated for the inclusion of a wide range of non-Russian ethnic groups under the new law, arguing that “military service presented the best means for ‘weakening tribal differences among the people’” (Sanborn Reference Sanborn2003, 65).

More recent examples illustrate the enduring appeal of the idea that the military can build political communities. In 1949, David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister of Israel, articulated a vision of the Israel Defense Force as a homogenizing entity that would “heal tribal and Diaspora divisions” (quoted in Cohen Reference Cohen1999, 388). Newly-independent Singapore introduced its 1967 National Service policy to bind together Singapore’s multi-racial population and inculcate the values of the nation (Ostwald Reference Ostwald, Ho and Ong-Webb2018, 125). Bucking a worldwide trend against the practice, the United Arab Emirates introduced conscription in 2014, a move that “can be seen as one of [the state’s] boldest efforts to involve the population in the construction of a shared Emirati consciousness” (Alterman and Balboni Reference Alterman and Balboni2017, 5). When Morocco similarly reinstated mandatory military service in 2018, official rhetoric stressed that service would inculcate patriotism and a sense of belonging to the homeland (North Africa Post 2018).

Mechanisms

These examples hint at two underlying mechanisms through which military service can integrate peripheral groups: socialization and contact. Although many organizations socialize their members, socialization is especially important for militaries because soldiers are asked—and, in the case of conscription, compelled—to risk their lives in service to their country. Inculcating patriotism and loyalty to that country, and encouraging individuals to see themselves as members of that country’s political community, are important tasks directly linked to the military’s ability to fight and win wars. Militaries thus act as “schools for the nation” by providing training in citizenship (Krebs Reference Krebs2004; Pye Reference Pye1961, 80). In Third Republic France, the military quite literally performed this function: an 1818 law “led to the creation of regimental schools where soldiers could learn how to read, write, and count—and what it meant to be a French citizen” (Weber Reference Weber1976, 298).

How might socialization foster the integration of peripheral groups such as minorities? One important aspect here concerns the forging of a broader national identity that can transcend more parochial ties (Gaertner and Dovidio Reference Gaertner and Dovidio2005; Transue Reference Transue2007). In identifying more strongly with the national identity of the dominant core, immigrants de-emphasize the boundaries separating themselves from the mainstream. Simultaneously, native-born individuals may perceive immigrants who serve in the military as more “legitimate” members of the national community. Both processes serve to facilitate social integration.

A second mechanism by which military service plays an integrative function for peripheral groups is via intergroup contact (Allport Reference Allport1954). Specifically, contact between immigrants and the core native-born population may debunk negative stereotypes, reduce intergroup anxieties, and forge friendships that create positive affective spillovers to other outgroup members. Moreover, the close nature of service in the military is particularly conducive to equal status as well as cooperative and institutionally-sanctioned contact, thereby fulfilling important scope conditions identified in Allport.

Extant research has produced evidence of positive contact effects running from core to peripheral groups.Footnote 4 Allport (Reference Allport1954, 277–8) himself highlights an earlier study from Stouffer’s volume on The American Soldier showing that white GIs in racially-mixed units in World War II were more favorably disposed to serving with African Americans. More recent evidence to the same effect is presented by Carrell, Hoekstram, and West (Reference Carrell, Hoekstra and West2019). In the Vietnam context, Green and Hyman-Metzger (Reference Green and Hyman-Metzger2024) showed that white men who were selected for the draft showed more positive racial attitudes, but that the effects faded over time.

THE VIETNAM WAR AND THE DRAFT LOTTERY

To circumvent the challenge of non-random selection into the military, we examine the effect of service on immigrant integration outcomes in the case of the Vietnam War. We mitigate concerns about self-selection by exploiting the Vietnam-era draft lottery system which randomized the probability of being called to serve. As scholars before us have argued, the lottery effectively operated as a natural experiment (Angrist Reference Angrist1990), thereby allowing us to estimate the causal effect of military service on integration.

Although US military involvement in Vietnam was initially advisory, combat operations began in 1965 after the Gulf of Tonkin incident. Troop levels escalated rapidly, peaking at over 500,000 in 1968. Over the course of the war, the US would deploy more than three million service members to Southeast Asia (Department of Veterans Affairs 2021). To meet these manpower needs, the government relied on conscription, and men ages 18–26 were required to register with the Selective Service System. Importantly for our purposes, registration applied even to resident non-citizens (i.e., immigrants).

In 1969, the Nixon Administration implemented a lottery system to determine the order of call. Each lottery applied to a cohort of men born in a certain year. The first lottery (December 1969) affected men born in the period 1944––1950. Subsequent lotteries involved 19-year-olds only. Thus, the July 1970 drawing involved men born in 1951, and the men born in 1952 were assigned draft numbers in August 1971. Although lotteries continued to be held every year until 1975, draft calls applied only to the first three lotteries. The last draft call took place in December 1972.

The draft lottery operated as follows. Random sequence numbers (RSNs) from 1 to 366 were randomly assigned to all dates of birth in the relevant birth cohorts. Each draft was also associated with an administrative processing number (APN), which designated the highest lottery number called that year. Men with an RSN at or below the ceiling were at risk for being drafted. The APN was 195 in the 1969 lottery, 125 in the 1970 lottery, and 95 in the 1971 lottery.Footnote 5 Although a number of deferments and avenues for avoiding the draft existed, past research has shown that the lottery functions as a strong instrument for Vietnam-era veteran status (Angrist and Chen Reference Angrist and Chen2011).

RESEARCH DESIGN AND DATA

Sample

Identifying an individual’s draft number (and hence draft risk) requires data on his exact date of birth. This information first becomes available in the restricted-use files of the long-form 2000 decennial census (Bureau of the Census 2000).Footnote 6 We focus on the population of male, draft-eligible, first-generation immigrants, defined as individuals who were born outside of the United States to non-American parents. Our sample also includes men born in US territories such as Guam and Puerto Rico who are arguably “foreign in a domestic sense” (Burnett and Marshall Reference Burnett, Marshall, Burnett and Marshall2001, 1). We further restrict the sample to those individuals who had arrived in the United States before 1969, the year of the first lottery drawing.

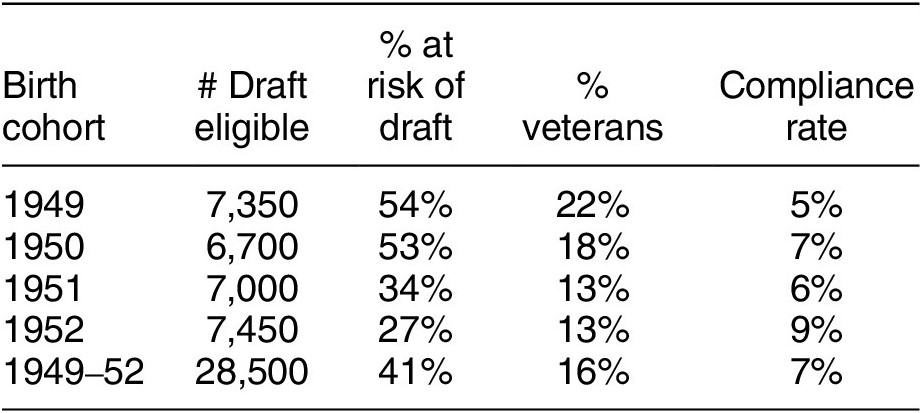

Turning to draft eligibility, this criterion could conceivably cover all men born between 1944 and 1952. However, in line with Angrist and Chen (Reference Angrist and Chen2011), our analyses show that the RSN is a weak instrument for the 1948 birth cohort, presumably because older individuals had already entered the military before the 1969 draft lottery (Table A6.2 in the Supplementary Material). We therefore focus our analyses on the 1949–52 birth cohorts, yielding a sample size of about 28,500 individuals of which approximately 17% served during the Vietnam era (Table 1).

Table 1. Estimates of Male Immigrant Population in 2000 Long-Form Census

Note: Immigrant counts are from the restricted-use 2000 decennial census. Observation counts are rounded to comply with Census Bureau policy. Results have been approved for release under FSRDC Project Number 2896 (CBDRB-FY24-P2896-R11129).

How does our sample fit into the larger context of immigration to the United States? In particular, for much of the first half of the twentieth century, the US operated a system of national-origin quotas that severely restricted immigration from non-Western countries. Thus, readers may be concerned that our sample is skewed toward European immigrants whose integration trajectories may differ in myriad ways from non-European immigrants.

While it is true that immigrants of European ancestry make up the the majority of foreign-born in 1970 in terms of raw numbers, a very different picture emerges when considering the cohorts of draft-eligible men, many of whom entered the US after the opening of immigration policy. Specifically, among men aged 18–21 in 1970, around 60% hailed from the “new” immigration countries. We detail these patterns in Section A2 of the Supplementary Material.

Estimation Strategy

We examine the effect of military service on integration outcomes using two-stage least squares regression. In the first stage, we model an individual’s Vietnam Veteran status as a function of his RSN and draft cohort:

where

![]() $ Draft\hskip2.77695pt risk $

= 1 if:

$ Draft\hskip2.77695pt risk $

= 1 if:

-

• RSN

$ \le $

195 for men born in 1949 or 1950,

$ \le $

195 for men born in 1949 or 1950, -

• RSN

$ \le $

125 for men born in 1951,

$ \le $

125 for men born in 1951, -

• RSN

$ \le $

95 for men born in 1952.

$ \le $

95 for men born in 1952.

Our first-stage specifications also contain a vector of covariates X including Year and Month of birth, Birthplace fixed effects, and the number of Years Since Immigration.Footnote 7

The second stage of our analysis examines the effect of service on our integration outcomes:

where

![]() $ {\hat{Veteran}}_i $

denotes Veteran status as predicted from the first stage, and

$ {\hat{Veteran}}_i $

denotes Veteran status as predicted from the first stage, and

![]() $ {Y}_i $

represents a range of integration outcomes described below.

$ {Y}_i $

represents a range of integration outcomes described below.

The output of this analysis represents estimates of the causal effect of military service for the population of compliers, that is, those individuals who served in the military if and only if they were assigned a draft number called for induction. These effects do not necessarily generalize to the entire population of foreign-born Vietnam veterans, as this population also includes true volunteers (always-takers) who would have joined the military regardless of their draft number.Footnote 8 Table 1 displays the number of draft-eligible individuals, the percentage of those at-risk and those who served, and the compliance rate.

Outcomes

We consider a broad range of behavioral outcomes to examine multiple facets of integration across the legal, linguistic, and social spheres. Our first measure is Naturalization.Footnote 9 The acquisition of American citizenship represents a key component in the political incorporation of immigrants (Fouka Reference Fouka2019; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2017), and citizenship itself can be a catalyst for further political and social integration (Hainmueller, Hangartner, and Pietrantuono Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Pietrantuono2017).

Our second set of measures capture the degree of Residential Integration at the census tract and census block-group levels. Residential selection into immigrant “enclaves” may lower both incentives as well as opportunities (through contact with the ethnic majority) to integrate into the mainstream (Danzer and Yaman Reference Danzer and Yaman2013).

Third, we focus on English language adoption (Bleakley and Chin Reference Bleakley and Chin2010; Harder et al. Reference Harder, Figueroa, Gillum, Hangartner, Laitin and Hainmueller2018; Lazear Reference Lazear1999). English adoption functions as a cultural signal of integration, while also signaling an ability to interact fully in the dominant language (Zhang and Lee Reference Zhang and Lee2020). We create two outcome measures of linguistic assimilation: English Only is an indicator for whether a person speaks only English at home, while English Ability is a scaled measure of how well a multilingual respondent speaks English.Footnote 10

Finally, our fourth set of measures focuses on marriage and partner choice. On the one hand, marriage patterns display a high degree of homophily and can be said to reflect in-group preferences and norms, as well as social distance between immigrants and the mainstream (Kalmijn Reference Kalmijn1998). On the other hand, marriage between immigrants and the native-born indicates a breakdown of parochial identities in favor of a broader national identity, and has even been termed “the final stage of assimilation” (Fouka, Mazumder, and Tabellini Reference Fouka, Mazumder and Tabellini2022, 820). We code two variants of this measure that capture increasing degrees of integration: marriage to a Non-Co-National Spouse and to a Native-Born Spouse.

Section A5 of the Supplementary Material examines the pairwise relationships between our different outcome measures. All variables move together in the expected direction.

RESULTS

Integration Outcomes

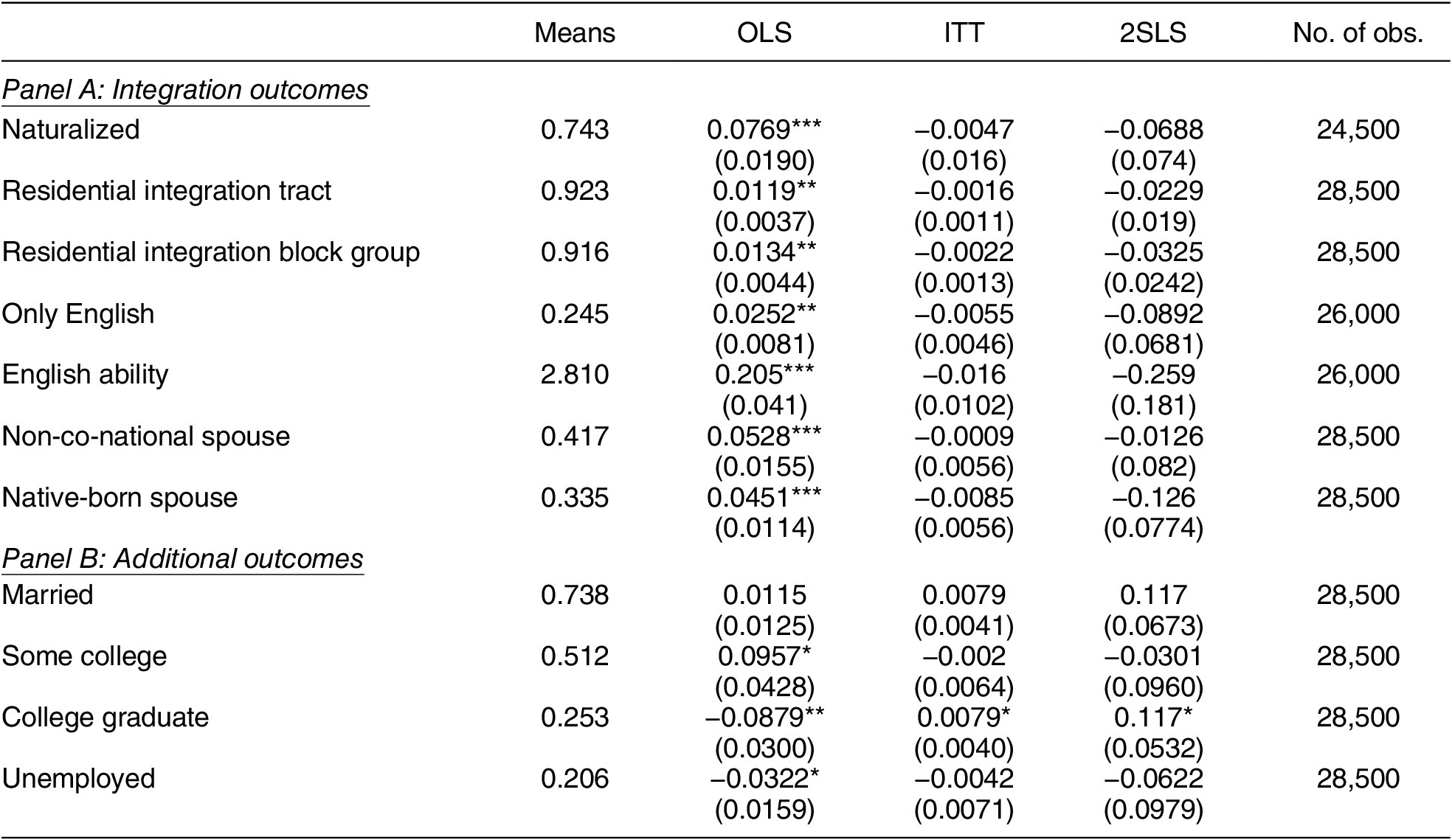

Panel A of Table 2 displays OLS, intention-to-treat (ITT), and 2SLS estimates of the effect of military service on integration outcomes, pooling across the 1949–52 birth cohorts. We observe from our OLS models that Veteran status significantly and positively predicts integration across all our outcome measures. However, a wholly different pattern obtains when we turn to Draft Risk: the (precisely-estimated) ITT coefficients are uniformly negative, substantively close to zero, and statistically insignificant. Consequently, we observe a similar pattern of null results in the 2SLS estimates. These latter findings thus suggest that the positive associations between Veteran status and integration outcomes are driven by self-selection into the military.

Table 2. Effect of Military Service on Integration, 1949–52 Cohorts

Note: *

![]() $ p< $

0.05, **

$ p< $

0.05, **

![]() $ p< $

0.01, ***

$ p< $

0.01, ***

![]() $ p< $

0.001. The table reports results for the effect of draft risk on integration outcomes. Dependent variables appear in the rows. Observation counts are rounded to comply with Census Bureau policy. Results have been approved for release under FSRDC Project Number 2896 (CBDRB-FY24-P2896-R11579 and CBDRB-FY25-0074).

$ p< $

0.001. The table reports results for the effect of draft risk on integration outcomes. Dependent variables appear in the rows. Observation counts are rounded to comply with Census Bureau policy. Results have been approved for release under FSRDC Project Number 2896 (CBDRB-FY24-P2896-R11579 and CBDRB-FY25-0074).

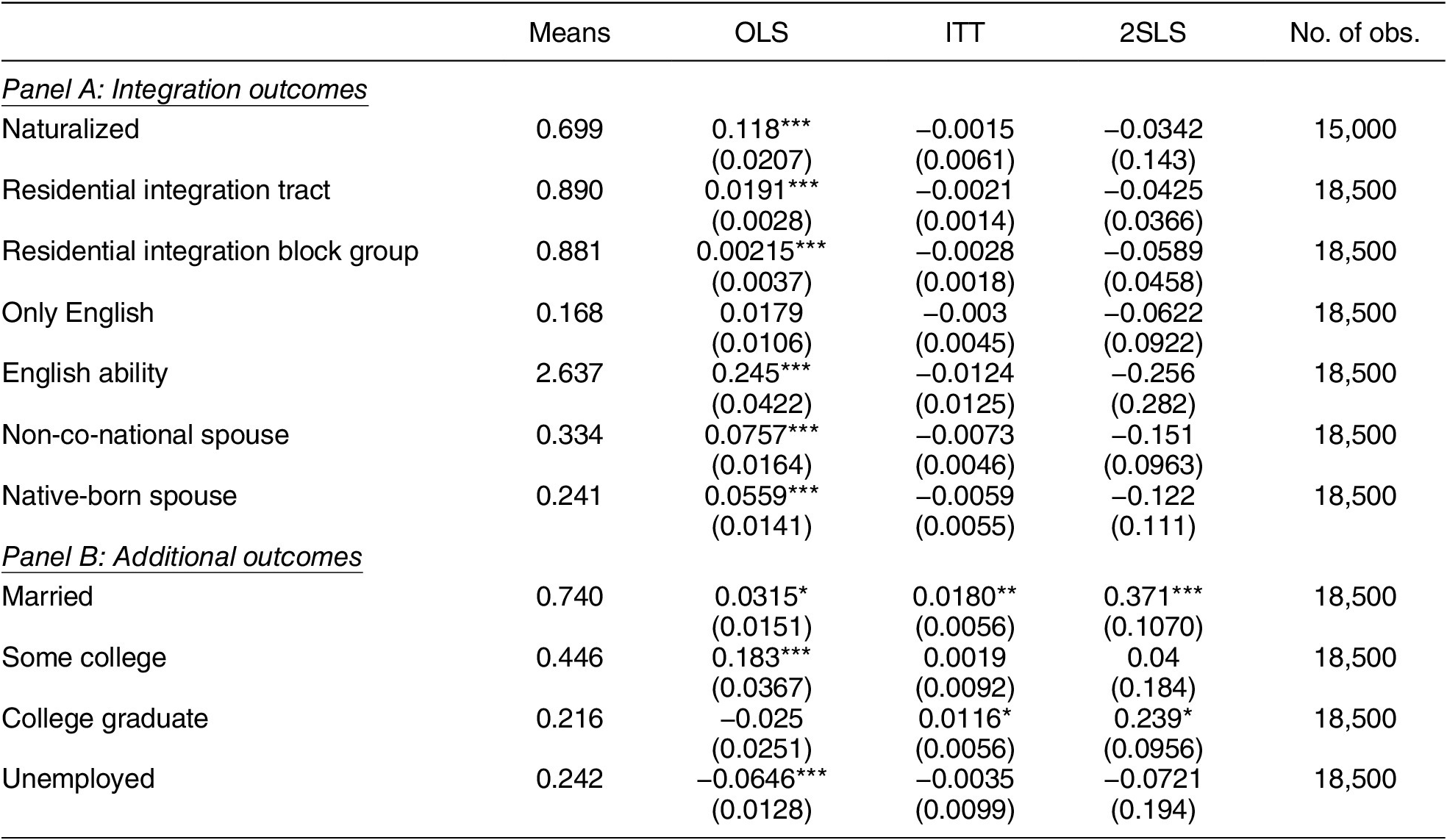

We conduct further subgroup analyses to examine whether the effects of military service differ between Western and non-Western immigrants. Specifically, we might expect more negative results for non-Western immigrants who were more “visibly” foreign and more likely to experience discrimination both inside and outside the military. Such experiences not only reflect a lack of acceptance from the mainstream, but could also lead to a backlash (Fouka Reference Fouka2020), especially if service raises expectations of equal treatment that go unfulfilled.Footnote 11

To examine this possibility, Panel A of Tables 3 and 4 replicate our analyses for Western and non-Western immigrants, respectively. We observe substantively similar patterns for both groups, indicating that our main results are unlikely to be driven by backlash effects.

Table 3. Effect of Military Service on Integration, 1949–52 Cohorts, Western-origin Immigrants

Note: *

![]() $ p< $

0.05, **

$ p< $

0.05, **

![]() $ p< $

0.01, ***

$ p< $

0.01, ***

![]() $ p< $

0.001. The table reports results for the effect of draft risk on integration outcomes. Dependent variables appear in the rows. Observation counts are rounded to comply with Census Bureau policy. Results have been approved for release under FSRDC Project Number 2896 (CBDRB-FY24-P2896-R11579 and CBDRB-FY25-0074).

$ p< $

0.001. The table reports results for the effect of draft risk on integration outcomes. Dependent variables appear in the rows. Observation counts are rounded to comply with Census Bureau policy. Results have been approved for release under FSRDC Project Number 2896 (CBDRB-FY24-P2896-R11579 and CBDRB-FY25-0074).

Table 4. Effect of Military Service on Integration, 1949–52 Cohorts, Non-Western-origin Immigrants

Note: *

![]() $ p< $

0.05, **

$ p< $

0.05, **

![]() $ p< $

0.01, ***

$ p< $

0.01, ***

![]() $ p< $

0.001. The table reports results for the effect of draft risk on integration outcomes. Dependent variables appear in the rows. Observation counts are rounded to comply with Census Bureau policy. Results have been approved for release under FSRDC Project Number 2896 (CBDRB-FY24-P2896-R11579 and CBDRB-FY25-0074).

$ p< $

0.001. The table reports results for the effect of draft risk on integration outcomes. Dependent variables appear in the rows. Observation counts are rounded to comply with Census Bureau policy. Results have been approved for release under FSRDC Project Number 2896 (CBDRB-FY24-P2896-R11579 and CBDRB-FY25-0074).

Additional Outcomes

Another possible explanation for these null results may be that military service did not provide tangible benefits to immigrants, or even imposed economic costs (Angrist Reference Angrist1990), thereby reducing their willingness to integrate or offsetting otherwise positive effects. To explore this possibility, we examine additional outcomes measured in the 2000 census: educational attainment as measured by having Some College experience and being a College Graduate as well as a measure for being Unemployed.Footnote 12 The results are reported in the bottom panels of Tables 2 – 4.

We find that instrumented military service has no effect on the likelihood of being Unemployed. This speaks against the argument that the draft imposed (long-term) economic costs.

Turning next to educational outcomes, we find that instrumented military service increases the chances of completing college or university. The effect is especially prevalent among non-Western immigrants. These results are unsurprising given that military service qualifies veterans for the GI Bill which subsidizes the costs of higher education (Angrist and Chen Reference Angrist and Chen2011). However, they speak against the argument that our null effects are driven by a lack of tangible benefits from military service. Furthermore, in the light of prominent theories linking educational attainment to social integration (Hainmueller, Hangartner, and Pietrantuono Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Pietrantuono2017; Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015),Footnote 13 these results suggest that—absent such educational benefits—outcomes for non-Western immigrants would have been even more negative.

Finally, we consider the effects of instrumented military service on whether an individual is Married at all. For non-Western immigrants, instrumented military service increases the baseline chances of marriage. This is important given that our marriage outcomes are coded 1 if married to a native-born spouse (or non-co-national spouse), and 0 otherwise. Since we find no effect of instrumented military service on marriage to a native-born or to a non-co-national, this must imply that these “extra” marriages among non-Western immigrants are endogamous. These results thus provide further evidence against a positive effect of military service on integration outcomes.

ADDRESSING THREATS TO INFERENCE

Attrition

Given our reliance on the 2000 census, there may be some attrition between the population of men initially exposed to the draft and the sample of individuals who appear in our data. Such attrition comes in two flavors: first, immigrants at risk of being drafted could be more likely to (permanently) emigrate, die, or otherwise be absent in the 2000 census, thereby biasing our results. Fortunately, we can directly test for this possibility by comparing the observed versus expected proportions of draft-eligible men appearing in 2000. As shown in Section A8 of the Supplementary Material, we detect no statistically significant deviations from expectations, indicating that attrition is not correlated with draft status.

A second issue concerns attrition that is unrelated to draft status. While this dynamic would not bias our results, it does speak to their generalizability, for example, if “low integration types” return permanently to their countries of birth, such that only “high integration types” remain in our sample (Emeriau and Wolton Reference Emeriau and Wolton2024). In such a scenario, our null results may be explained by long-run convergence between non-veterans and veterans with “above-average” integration potential.

While integration potential is of course unobservable, we do attempt to gauge the scope of this problem by comparing birthplace-specific counts of immigrants in the 1970 census against individuals in the 2000 census who report having immigrated before 1970.Footnote 14 Details can be found in Section A9 of the Supplementary Material. For the most part, we find that the 2000 counts are comparable to the 1970 counts. We do find a decrease in the counts of men born in the US territories and Canada, which may reflect the ease of travel to these places. As detailed in Section A10 of the Supplementary Material, we conduct robustness checks where we drop these immigrants. Our results are unchanged.

One prominent exception to the pattern just described concerns Mexican-born individuals. Here, we find that there are significantly more men in 2000 who claim to have immigrated before 1970 than actually appear in the 1970 census count. Interestingly, we find the same pattern for Mexican-born women who were not subject to the draft (see Figure A9.12), suggesting that the 1970 “undercount” is not simply capturing draft dodging. Rather, we can think of two possibilities: (i) Mexican-born individuals in 2000 were mis-reporting their date of immigration to the United States and/or (ii) Mexican-born individuals in 1970 were not “found” by census-takers. In either case, it appears that a significant portion of Mexican-born individuals in our 2000 sample were not exposed to the draft lottery,Footnote 15 either because they were living in Mexico, or because they had such a transient status in the United States that they escaped the notice of census workers. As such, both the ITT and the 2SLS estimates for Mexican-born are likely to be biased. For robustness, we therefore re-estimate our models dropping the Mexican-born. Our results are unchanged.

Potential Exclusion Restriction Violations

Could the draft lottery affect outcomes though other channels, thereby violating the exclusion restriction? We examine educational deferments as one potential violation. Men at risk of being drafted may have sought college deferments, thereby raising the integration level of the comparison group in a way that is unrelated to military service itself. To examine this possibility, Table A11 in the Supplementary Material compares 2SLS estimates for those 1949–51 cohorts that could have sought out deferments against the 1952 cohort drafted after the deferments policy ended. Results are similar across both groups, suggesting that deferments are unlikely to be major source of bias.

We also investigate whether non-permanent emigration as a form of draft avoidance may violate the exclusion restriction. Immigrants at risk of being drafted could have emigrated to their origin countries during the war and returned to the United States after the war. In this case, time outside the country could have decreased their likelihood of integration as a function of their draft number but not military service.

Of course, we cannot directly observe such “circular migration” in our data. However, we assume that circular migration is easier for men born in Canada and Mexico—due to these countries’ proximity to the United States—than for men born in, say, Hungary or Italy. We therefore exclude Mexican- and Canadian-born immigrants in robustness analyses. As shown in Section A10 of the Supplementary Material, dropping these groups does not substantially affect our estimates, suggesting that circular migration is an unlikely source of bias.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Overall, our findings cast doubt on the integrationist view of military service. The strong positive effects of military service evident in our OLS models disappear entirely when we instrument for service using the draft lottery. The disparity in results between the OLS and 2SLS models suggests a self-selection story consistent with historical accounts of immigrants voluntarily serving to demonstrate their patriotism and loyalty to their new country (Burk Reference Burk1995; Kimura Reference Kimura1988, 196–200).

We should note that our null results contrast with studies from Spain (Bagues and Roth Reference Bagues and Roth2023; Cáceres-Delpiano et al. Reference Cáceres-Delpiano, De Moragas, Facchini and González2021), Argentina (Ronconi and Ramos-Toro Reference Ronconi and Ramos-Toro2025), Finland (Finseraas and Kotsadam Reference Finseraas and Kotsadam2017; Finseraas et al. Reference Finseraas, Hanson, Johnsen, Kotsadam and Torsvik2019), and the United States (Carrell, Hoekstram, and West Reference Carrell, Hoekstra and West2019; Green and Hyman-Metzger Reference Green and Hyman-Metzger2024) showing that military service improves intergroup attitudes and behaviors. In the closest study to our research, Mazumder (Reference Mazumder2017) finds positive effects of World War I military service on naturalization, marriage to native-born Americans, and the adoption of “American” (i.e., Anglo) naming conventions.

In our case, why did military service not have the integrating effects that some scholars have predicted? Racial discrimination in the US military, which was pervasive during the Vietnam era (Bailey Reference Bailey2023; Westheider Reference Westheider1997), could have undermined the intergroup contact mechanism or the socializing power of pro-America messages. However, the consistency of our findings across Western and non-Western immigrants suggests that discrimination is unlikely to explain the null results.

A second possible explanation relates to our focus on (long-term) behavioral outcomes. Initial differences caused by military service may have dissipated over the long run (Angrist and Chen Reference Angrist and Chen2011). Examining over four decades of data from the General Social Survey, Green and Hyman-Metzger (Reference Green and Hyman-Metzger2024) find that the effects of the Vietnam draft on racial attitudes diminished over time, thereby suggesting a pattern of long-term convergence. In line with this interpretation, we show in Section A7 of the Supplementary Material that compliers are on average initially more integrated than the full sample—i.e., they immigrated to the US at a younger age, and also came disproportionately from Western, English-speaking countries (particularly Canada). Given this profile, it is possible that undrafted non-veteran compliers may have caught up with their drafted veteran counterparts by the year 2000.Footnote 16

A final possible explanation lies with our choice of case. Although the Vietnam War offers a unique opportunity to address the self-selection challenge, the conflict was deeply unpopular and ended in the ignominious withdrawal of the US military from Saigon in 1975. Whereas veterans who served in “good wars” such as World War II were celebrated as heroes, Vietnam-era veterans are remembered for the hostility and scorn that greeted them upon their return, and many soldiers also questioned the legitimacy of US motives in the conflict (Baskir and Strauss Reference Baskir and Strauss1978). The specific character of the Vietnam War thus points to military victory, legitimacy and public support as potentially important scope conditions for the integrationist view. We leave these avenues for future research.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542500019X.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/O80SKQ. Limitations on data availability are discussed in the text and Supplementary Material.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project is one of several joint projects by the authors. Author names appear in reverse alphabetical order and reflect a principle of rotation. We are grateful to Joe Ballegeer for assistance with the restricted-use data. Any views expressed are those of the authors and not those of the U.S. Census Bureau. The Census Bureau has reviewed this data product to ensure appropriate access, use, and disclosure avoidance protection of the confidential source data used to produce this product. This research was performed at a Federal Statistical Research Data Center under FSRDC Project Number 2896 (CBDRB-FY24-P2896-R11129, CBDRB-FY24-0364, CBDRB-FY24-P2896-R11579, and CBDRB-FY25-0074).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human participants.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.