The idea that humans share “culture” is arguably foundational to anthropology, yet scholars consistently disagree on culture's genesis, reproduction, and purpose. To some, culture is an adaptive mechanism, intervening where our biological capacities are outmatched by externally imposed circumstances, like climate change or foraging needs. To others, culture is normative and mentalist in corresponding to the symbolic structures (i.e., norms) of a given group of people (for a review, see Watson Reference Watson1995). In both cases, culture is bounded, self-replicating, and thus, in theory, maps neatly onto what anthropologists have described as “culture areas” (e.g., Graeber and Wengrow Reference Graeber and Wengrow2021:171). However, many have challenged this view by showing how cultures are relational entities formed through interactions between social Others (Wolf Reference Wolf1984).

Graeber and Wengrow (Reference Graeber and Wengrow2021) revisited the issue, noting that neighboring cultures form in opposition, being fully aware of one another's politics, social arrangements, and philosophical canon. They also argue that socially and materially diverse boundary zones emerge through these processes of identity formation. Echoing this claim, Sassaman and Gilmore (Reference Sassaman and Gilmore2021) demonstrate how frontiers can become hubs of innovation and thus affect the social and historical trajectories of entire regions. To this end, we report trends in pottery distribution alongside preliminary petrographic data of the Late Woodland component of Esseneca (38OC20), South Carolina, in the United States. Patterns in our data show two main trends: (1) pottery types common to the Georgia Piedmont and Carolina Coastal Plain co-occur in parts of the South Carolina Upstate, and (2) Late Woodland potters in the region collected a broad swath of clays during seasonal foraging cycles. We argue that Late Woodland foragers freely traveled about the region and thus encountered a range of social groups throughout the year, laying the foundation for some aspects of Mississippianization.

Pottery Traditions and Considerations of Chronology

Americanist archaeologists largely consider the Savannah River an eastern boundary for the distribution of Swift Creek Complicated Stamped pottery (Smith and Stephenson Reference Smith and Stephenson2018; Williams and Elliot Reference Williams, Elliott, Williams and Elliott1998:6). In contrast, fabric-impressed and cord-marked wares are more common to the Yadkin, Mount Pleasant, and Cape Fear traditions of the Carolinas (Herbert Reference Herbert, Anderson and Mainfort2002; Patch and Espenshade Reference Patch and Espenshade2020). Showing roots in the Early Woodland (around 200 BC), Swift Creek pottery production and exchange expanded over the next few centuries to incorporate communities across southeastern North America (Wallis Reference Wallis2011). The ornate and innovative designs of Swift Creek paddles broke from the comparatively mundane canon of earlier check-stamped traditions that mostly served routine economic purposes (Anderson and Sassaman Reference Anderson and Sassaman2012:115–121; Smith and Knight Reference Smith and Knight2017).

Swift Creek followed on the heels of Hopewell, an efflorescence of ceremonial activity that connected social groups across the Eastern Woodlands. Swift Creek communities eventually anchored Hopewell's corresponding religiosity and social interaction at civic-ceremonial centers that swelled during seasonal ritual cycles and compressed as visitors returned to their natal villages (Pluckhahn Reference Pluckhahn, Bandy and Fox2010). Civic-ceremonial life was organized around crafting, mortuary ritual, and, most notably, mounding. However, aspects of civic ceremonialism waned during the Late Woodland transition as social groups became increasingly fragmented and, in the Georgia and Carolina Piedmont, organized fluidly to exploit uplands adjacent to floodplains (Herbert Reference Herbert, Anderson and Mainfort2002; King and Stephenson Reference King, Stephenson and King2016:36; Markin Reference Markin, Gougeon and Meyers2015).

Although some Woodland mortuary mounds are known in the Carolinas, most sites fall outside the sphere of civic ceremonialism. Communities in the region embraced what Anderson and Sassaman (Reference Anderson and Sassaman2012:112) call “Woodland Regionalism,” characterized by increasing social and material differentiation across the Southeast and American Midwest. Currently, there is little evidence for substantial mixing of complicated stamped and fabric-impressed/cord-marked wares in the region.

Site Background and Sampling Strategy

Esseneca is located on an upland ridge, roughly 45 km south of the Eastern Continental Divide on what is now Clemson University's main campus (Figure 1). It lies within the Walhalla nappe of the Carolina Piedmont, an autochthonous metamorphic zone adjacent to the Blue Ridge Mountains (Griffin Reference Griffin1974). Pottery was encountered in all 18 of the 1 × 2 m units excavated over the course of two field seasons. Levels were excavated in 10 cm intervals, except where slope or modern disturbance necessitated a 20 cm interval for the first level. Artifact densities in each unit were comparatively low, suggesting that the site was a small seasonal encampment, such as those described by Markin (Reference Markin, Gougeon and Meyers2015:3–4). It is worth noting that the site is adjacent to what was once the Seneca River, thus aligning with Cobb and Garrow's (Reference Cobb and Garrow1996) observation that late Woodland communities settled around major rivers as opposed to tributaries (Markin Reference Markin, Gougeon and Meyers2015:3). Although the site is a possible location of the contact-era Cherokee village of Esseneca, most diagnostic lithics and pottery belong to Woodland Yadkin and Swift Creek phases, respectively.

Figure 1. Map of Esseneca (38OC20).

Vessels served as the unit of analysis for the petrographic component of this study. Where possible, they were first differentiated by rim form and shape. However, because rims are comparatively scant in the assemblage, vessel lots were mostly established through surface treatment and temper. All vessels (N = 62) from the 2021 excavations that could be differentiated based on the aforementioned criteria were selected for petrographic sampling. Sampling was restricted to the 2021 excavations because the 2022 assemblage was unanalyzed when thin sectioning occurred. Pottery from all the excavations has since been analyzed and is reported in the following section.

Petrographic work centered on the qualitative analysis of fabric and textural groups. Petrofabric groups were based on mineral content and abundance following Rice (Reference Rice2015:269; Table 1), and temper type and abundance formed the basis of textural categories (e.g., Cordell Reference Cordell, Cordell and Mitchem2021:161). Particles were typically measured using the 10× objective, although 25× was sometimes used to identify small particles and micas, and 5× was used where appropriate to measure granule or larger particles. Crosshair intervals for each objective were calibrated using a stage micrometer following the Wentworth (Reference Wentworth1922) system of measurement.

Table 1. Mineralogical Composition of Petrofabric Groups Identified in This Study.

Note: Analytical protocols for determining particle abundance followed Rice (Reference Rice2015:269).

Provenance was assessed by comparing the mineralogy of petrofabric groups to that of primary rock formations of the Walhalla nappe (Griffin Reference Griffin1974). We adopted a modified version of the Miksa and Heidke's (Reference Miksa and Heidke2001) petrofacies approach to assessing vessel provenance and clay procurement (e.g., Eckert et al. Reference Eckert, Schleher and James2015). Although mineralogy in the Carolina Piedmont cannot be associated with distinctive river valleys, there is sufficient variation among formations of the Walhalla nappe to assign petrofabrics to general procurement zones. To remove bias from the analysis, petrofabrics were assigned to vessels before the analyst knew the form and design of the sherd (e.g., Hegmon et al. Reference Hegmon, Nelson and Ennes2000).

Patterns and Trends

Chronology and Type Distribution

A radiocarbon assay extracted from soot that adhered to the rim surface of a complicated stamped vessel yielded a two-sigma probability range (95.4%) of AD 677–873 (OxCal v4.4.4). The complicated stamped motifs on much of our assemblage are conspicuously thin and bear resemblance to the late Swift Creek Napier series (e.g., Markin Reference Markin, Gougeon and Meyers2015), providing further evidence for the Late Woodland occupation at the site. Although some documentary sources place the Cherokee town of Esseneca on Clemson University's campus, most of the site resided in the Seneca River floodplain, now under Lake Hartwell. Further, this assemblage yields no evidence of the filleted, pinched rims common to Cherokee/Lamar pottery. On the contrary, rims are mostly folded and resemble the Napier series. Of the 1,120 sherds identified in the assemblage, roughly 30% were decorated, and 7% (n = 151) exhibited clear surface treatments that were assigned to formal types.

Complicated stamped pottery constitutes nearly half of the decorated component of the assemblage (Figure 2). The relatively even split between curvilinear and rectilinear variants of complicated stamped sherds carries interesting temporal connotations. Julie Markin (Reference Markin, Gougeon and Meyers2015) noted a clear tapering of curvilinear motifs during the emergent Mississippian phase in north Georgia. Conventional wisdom holds that rectilinear diamond motifs gained traction during the late Swift Creek phase, increasing to nearly replace curvilinear designs by AD 900. The relatively even representation of both variants likely places the assemblage at the incipient stages of Napier and Woodstock, when curvilinear designs were popular but were also being influenced by people familiar with diamond and line-block motifs. Fabric-impressed pottery also occurs in high proportions, constituting roughly 30% of the decorated assemblage. Check stamped is the next most common type, at 15%, and cord-marked, brushed, simple stamped, and incised wares occur in minor proportions at less than 5% each.

Figure 2. Site-level pottery distribution by surface decoration.

Of course, site-level analyses potentially gloss meaningful temporal variation. It is possible that the complicated stamped and fabric-impressed wares are from different components and thus should, in theory, be separated spatially, stratigraphically, or both. Our data reveal this not to be the case, however. Area 1, consisting of test units one through six, occupies a relatively low-lying section of the upland ridge and sits beneath Area 2, which rests atop a terraformed platform. It then stands to reason that earlier deposits, if present, should occur in Area 1. We find no such distinction in our units: patterns in pottery distribution are strikingly similar across the site. Complicated stamped types represent 42% and 49% of the decorated components of Areas 1 and 2, respectively, and fabric-impressed wares constitute around 30% of each area. It is worth noting that although agricultural activities during the early to mid-twentieth century may have disturbed and comingled the uppermost strata at the site, the majority of the assemblage is conspicuously Late Woodland.

Petrography

Five primary petrofabric groups were identified in this analysis (Table 1), and all map well onto local geology. Groups A, B, and C contain the weathered clasts of micaceous feldspathic quartzite, which is pocketed in the Walhalla nappe. Group A is the most weathered variant, containing mostly quartz and feldspar, whereas Group C is relatively rich in mica and kyanite (Figure 3). Groups D and E are composed of amphibole, feldspar, and epidote and are differentiated by the presence/absence of mica (Figure 4). These groups are most clearly associated with amphibolites and amphibole gneisses documented within the “Clemson Window” section of the Walhalla nappe and are most proximate to the site (Griffin Reference Griffin1974:1126–1128). Samples are split relatively evenly among the two main rock groups: 61.2% were assigned to feldspathic groups A through C, and nearly 40% were assigned to amphibole-rich groups D and E. Complicated stamped pottery is well represented in both feldspathic- and amphibole-rich groups, at 53.6% and 46.6%, respectively. Check-stamped pottery is also relatively evenly distributed among petrofabrics, whereas 90% of fabric-impressed samples are members of amphibole-rich groups.

Figure 3. Thin-section photo highlighting micaceous, kyanite-rich petrofabric Group C (taken at 5× magnification under cross-polarized light). (Color online)

Figure 4. Thin-section photo highlighting amphibole-rich petrofabric Group E (taken at 5× magnification under plane-polarized light). (Color online)

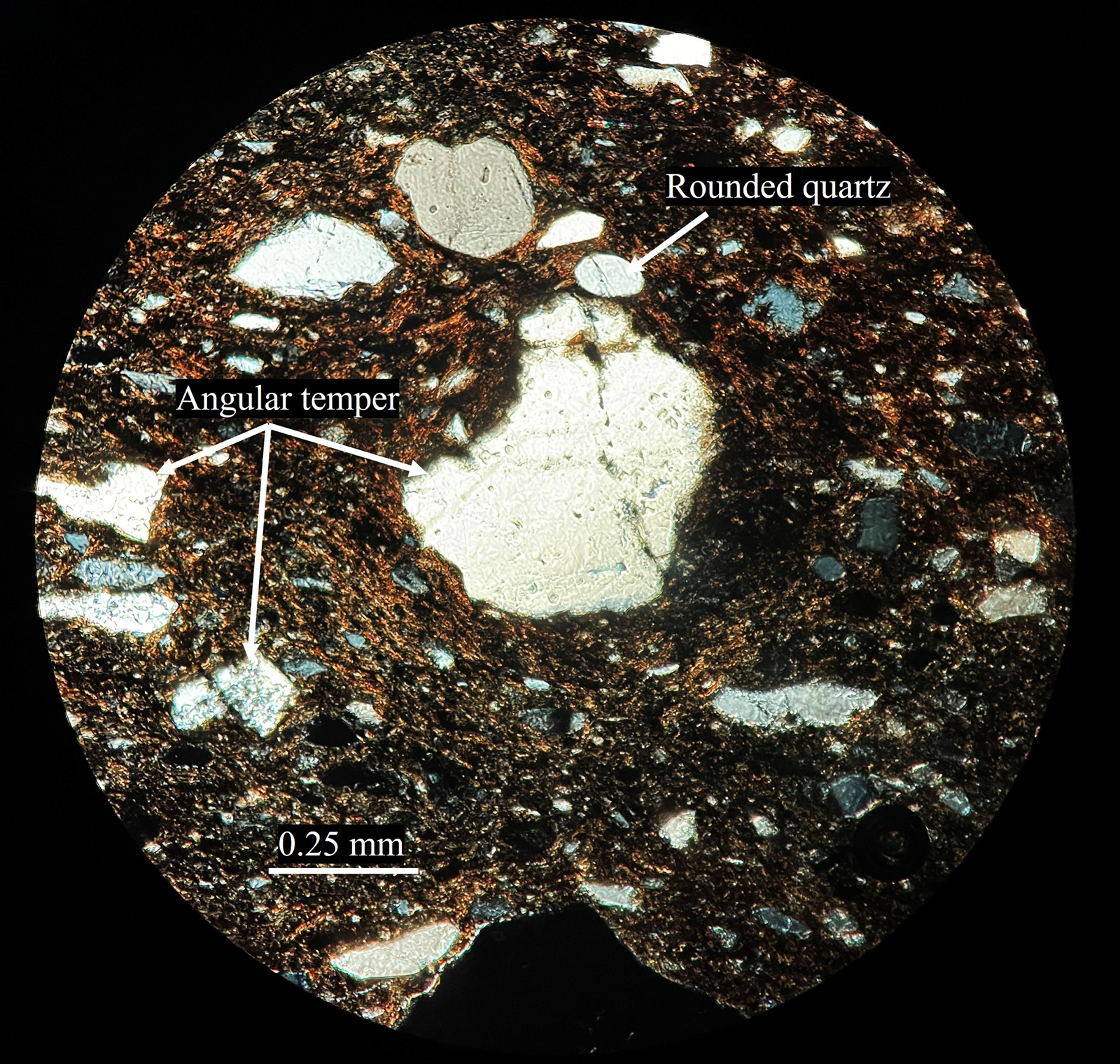

The petrographic samples are invariably grit tempered and were assigned to either sand/grit or grit textural groups. Although a range of fine to granule-sized particles are present in all samples, coarse to granular particles are more abundant in the grit group. The copresence of smaller, rounded grains (subject to weathering) and of larger grains with angular borders in most samples suggests that potters intentionally crushed sands and rock fragments and added them as temper (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Thin-section photo contrasting rounded, weathered particles with angular temper (taken at 10× magnification under cross-polarized light). (Color online)

Discussion

Several trends are apparent in these data. First, Late Woodland potters in the region produced a range of pottery types characteristic of two distinctive culture historical traditions: (1) complicated stamped to the west and (2) fabric impressed to the north and east. Although it is possible that vessels made their way to the site through exchange, the lack of variation in tempering suggests that most potters were members of the same community of practice. We interpret these patterns as evidence that potters moved freely about the landscape, incorporating traditions of different social groups into their daily potting routine, possibly at different points during the year.

Further supporting this argument are trends in the petrofabric data that identify two main clay procurement zones within the Walhalla nappe formation of the South Carolina Upstate. Amphibolites and amphibole gneisses are abundant in the immediate vicinity of the site, yet micaceous feldspathic quartzites appear in outcrops less than 5 km away (Griffin Reference Griffin1974). Clays near both formations would have clearly been accessible for Late Woodland potters. Inasmuch as we can extrapolate from the comparison of the mineralogy of the pottery with local geology, potting practice at the site was almost exclusively local.

That local villagers provisioned their own needs during seasonal foraging rounds is not surprising. Although we have no direct evidence for inferring seasonality, these data do show that potters were highly mobile and were thus unaffected by the territoriality known to the Mississippian, for example. Buchanan (Reference Buchanan and Benfer2017) and Fowles and colleagues (Reference Fowles, Minc, Duwe and Hill2007) have extensively documented how warfare and political competition circumscribe potters’ movements. In extreme cases, potters may be forbidden from accessing clays outside the immediate vicinity of their village (e.g., Fowles et al. Reference Fowles, Minc, Duwe and Hill2007). The data we present in this study suggest much the opposite.

We now return to our opening discussion of culture and social boundaries. Although it may be tempting to view social groups that borrow potting traditions from cultural “heartlands” as unimaginative, we may reach a different conclusion when expanding the discussion beyond surface treatment. Clearly, Late Woodland potters traversed a variety of cultural boundaries while collecting clays. It is also likely that the community inhabiting the site retained close ties with other communities through some forms of exchange. Because our data suggest that most pottery was made locally, implements, such as wooden paddles used to impress designs, may have been brought in through postmarital residence patterns. Viewed this way, Esseneca potters were cosmopolitans, almost certainly women, who encountered a broad spectrum of social and political arrangements and thus acted as political mediators between communities.

What impact could these people (or people like them) have had on the decision to settle as floodplain agriculturalists several centuries later? In the South Carolina Upstate, small, scattered villages of the Late Woodland eventually transformed into sedentary mound centers during the Mississippian (Anderson Reference Anderson1994). Many local Mississippian settlements, like Chauga Mound, have Late Woodland roots (Rodning Reference Rodning2015). Although archaeologists typically consider the relatively egalitarian foragers of the Late Woodland as antithetical to Mississippians, there may be some ways in which mobile lifestyles anticipated aspects of later sedentism. For instance, Graeber and Wengrow's (Reference Graeber and Wengrow2021) recent review of ethnographic research highlights the plasticity of human social organization, noting that seasonally mobile groups often constructed rigid, top-down hierarchies, only to raze them a season later when families and individuals regained their autonomy. This type of flexibility in social organization can be particularly common in frontier communities where labor shortages promote task sharing between settlements and discourage craft specialization (Herr Reference Herr2001:92).

At this point, we cannot say whether the inhabitants of Esseneca experimented with such polar extremes. It is reasonable to suggest, however, that mobile foragers moving about the landscape would have experienced enough variety socially to predict what life might be like in sedentary villages, under the control of relatively few people, as was the case during the Mississippian. Given that so many Mississippian villages in the region have Late Woodland roots, it is clear that mobile communities eventually agreed that the social diversity they encountered seasonally could (and should) be organized into a more permanent arrangement.

Acknowledgments

We owe our sincere thanks and gratitude to the following individuals and institutions for supporting this project: the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians; Stephen Yerka; the Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Criminal Justice and the Department of History and Geography at Clemson University. We also thank each reviewer for their insightful and measured critiques.

Funding Statement

This project was funded by National Park Service Grant no P21AP11636-00 and by the Faculty Development Research Program administered by the College of Architecture, Arts, and Humanities at Clemson University.

Data Availability Statement

All pottery and thin sections analyzed in this study are curated at the Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Criminal Justice at Clemson University.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.