Introduction

This paper considers how a diagnosis of dementia affects people's planning for future social care needs and associated costs.

Social care in England is funded through a combination of state funding and individuals' private resources. Eligibility for state-funded social care involves a needs test and a means test. The majority of older people pay a means-tested contribution towards their social care, but people with savings and assets above a nationally set threshold pay all of the costs themselves; the latter are known as ‘self-funders’. The threshold, known as the upper capital limit, is currently £23,250 (excluding a person's home if they or a dependent live in it). There are plans to introduce a new £86,000 cap on the amount anyone in England spends on personal care over their lifetime and the upper capital limit will be increased from £23,250 to £100,000 (HM Government, 2021). This means that people with up to £100,000 in savings and assets will pay a means-tested contribution to personal care costs rather than automatically paying the full amount. Those with above £100,000 will still pay the full amount. People will continue to pay until they have spent £86,000 on eligible personal care. Accommodation and living expenses (known as daily living or ‘hotel costs’) are not included in the £86,000 cap.

There are no precise figures for the number of older self-funders in England. The Office for National Statistics (2022) estimated 35 per cent of care home residents in 2020/21 were self-funders. But care homes are only part of the story; many more people receive care in their own homes, typically from private or third-sector agencies or individuals. There are no up-to-date estimates of the number of people self-funding in their own homes, but Henwood et al. (Reference Henwood, McKay, Needham and Glasby2019) suggest there are around 350,000 self-funders in England, with 50 per cent more people self-funding care at home than in residential care. People living in their own homes also rely on unpaid care from family and friends. The National Audit Office (Comptroller and Auditor General, 2021) cites data suggesting between 10 and 17 per cent of people aged over 16 provide unpaid care to adults. Furthermore, it is estimated that 7 per cent of the population aged 65 and over has some unmet needs (Age UK, 2019).

Social care is expensive. Home care costs in England are currently around £25 an hour. Self-funding care home residents typically pay over £3,500 a month for residential care, and substantially more for nursing care. Thus, the cost to individuals over a number of years can reach tens, and for some people, hundreds of thousands of pounds. Running out of money to spend on care or leaving no inheritance are common concerns (Henwood and Hudson, Reference Henwood and Hudson2008; Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Heavey and Birks2017; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Trathen, Wittenberg, Mays, Wistow and Knapp2019). However, despite these potentially huge sums, there is evidence that self-funders do not think in advance about the costs of their care or plan how they will manage their finances to pay for it (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Trathen, Wittenberg, Mays, Wistow and Knapp2019; Heavey et al., Reference Heavey, Baxter and Birks2019).

One reason for failing to plan is that people often do not understand the social care system and so do not realise that they may need to pay for care (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Heavey and Birks2017; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Trathen, Wittenberg, Mays, Wistow and Knapp2019). Another is that people do not expect to need care. About 7 per cent of people aged over 65 in England in 2020 were receiving home care (National Audit Office, 2021), and only 4 per cent of people aged 65 or over in the United Kingdom (UK) live in care homes, rising to 15 per cent aged 85 or over (Methodist Homes, 2022). It is therefore understandable that people see little reason to plan for something they perceive as unlikely to happen. A further reason is that people place a higher value on the present than on the future, so incentives to take action now which have an impact on the future are weak (Broome, Reference Broome1994; Heilmann, Reference Heilmann2017).

There is also research suggesting people struggle with navigating the complex UK care systems (Peel and Harding, Reference Peel and Harding2014; Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Wilberforce and Birks2020b). The challenges of doing so as (or for) a person with dementia can create additional uncertainty and concern about making the ‘wrong’ choices as well as continued reflection on decisions after they have been made (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Samsi and Manthorpe2018), potentially perpetuating any feelings of uncertainty and/or regret. In addition, fear of being dependent, anxieties about care costs and fear of being unable to pay can deter people from thinking about future care needs (DaDalt and Coughlin, Reference DaDalt and Coughlin2016; Heavey et al., Reference Heavey, Baxter and Birks2019) and can ‘paralyse’ people into inaction (Price et al., Reference Price, Bisdee, Daly, Livsey and Higgs2014).

Yet lack of planning for care and its costs can mean people feel ill-prepared and pressured into making care choices at crisis points when emotions are already strained and options limited. Some people are diagnosed relatively early with conditions that increase their chances of needing care in the future. There are important questions about whether such diagnoses might motivate planning for the costs of care.

Dementia is one such condition. People with dementia face an increased possibility that they will need social care support. It is estimated that about 60 per cent of people receiving home care in the UK (Alzheimer's Research UK, nd) and 70 per cent of people in care homes have dementia (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Arthur, Barnes, Bond, Jagger, Robinson and Brayne2013). However, there is a high level of uncertainty about how quickly, for any particular individual, dementia will progress and the nature of increased need. There is evidence that many people with dementia prefer to focus on the here and now (Dickinson et al., Reference Dickinson, Bamford, Exley, Emmett, Hughes and Robinson2013; Hellström and Torres, Reference Hellström and Torres2016) or actively avoid people and places associated with more advanced dementia in order to maintain some distance from their potential futures (Thuesen and Graff, Reference Thuesen and Graff2022). But it is also increasingly clear that many people with dementia are concerned about their future living arrangements, often expressing a preference to stay living independently at home rather than move to residential care (Heaton et al., Reference Heaton, Martyr, Nelis, Marková, Morris, Roth, Woods and Clare2021). Therefore, although people may actively avoid thinking about the future, the fact that they are aware of potential changes and have preferences for how they wish to live, suggests they might also see the value in planning to make these preferences a reality. That they do not do so now may represent a failure of current systems of diagnosis and support.

It is axiomatic that people with dementia's cognitive capacity to engage with decision-making declines over time. This applies to many entering the last stages of life, not just those with moderate to severe dementia (Brayne et al., Reference Brayne, Gao, Dewey and Matthews2006). It can therefore be argued that people with dementia should be helped to engage in planning as early as possible to ensure that their wishes for future care and associated financial arrangements are known and can be met. Indeed, evidence suggests that people recognise this need to engage whilst still capacitous and operate ‘under the assumption that their future ha[s] already shrunken’ (Hellström and Torres, Reference Hellström and Torres2016: 1581). There are over 200,000 new cases of dementia each year in the UK (Alzheimer's Research UK, nd). Just over half of people aged over 60 and living with dementia are estimated to be in the early stages (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Knapp, Guerchet, McCrone, Prina, Comas-Herrera, Wittenberg, Adelaja, Hu, King, Rehill and Salimkumar2014). Thus, there is a substantial number of people with the opportunity, and possibly the motivation, to consider their future care needs and the associated financial implications while still able to engage.

Following a diagnosis, people with dementia typically attend follow-up appointments with specialist services such as a memory clinic or are discharged to the care of their general practitioner. These follow-up appointments are opportunities to assess the progress and impact of the condition, and to discuss its implications for the short, medium and long term. There are chances to talk about issues such as Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA), welfare or financial needs, and opportunities to make advance statements about future care wishes. However, such conversations, despite being recognised as important, are rare (Poppe et al., Reference Poppe, Burleigh and Banerjee2013; Piers et al., Reference Piers, Albers, Gilissen, De Lepeleire, Steyaert, Van Mechelen, Steeman, Dillen, Vanden Berghe and Van den Block2018).

Many people who receive a diagnosis of dementia will have a partner or other family member who supports them and whose role often develops into that of unpaid carer (hereafter ‘carer’) as the individual requires greater support to remain independent. Over time, the carer's role can develop into decision-maker with or on behalf of the person with dementia. The decision-making process for carers of people with dementia has unique elements that make this process time-consuming and emotional, including difficulty accepting the diagnosis and the progressive nature of dementia (Wolfs et al., Reference Wolfs, de Vugt, Verkaaik, Haufe, Verkade, Verhey and Stevens2012). Furthermore, carers can feel too drained by the day-to-day issues and tasks of caring for a relative with dementia to think about the future (Harrison Dening et al., Reference Harrison Dening, Sampson and De Vries2019). However, some later-life or post-mortem events are more commonly planned for, e.g. wills, LPA and funeral costs (Price et al., Reference Price, Bisdee, Daly, Livsey and Higgs2014).

Engagement with care-related planning, including advance care planning, is limited (Knight et al., Reference Knight, Malyon, Fritz, Subbe, Cooksley, Holland and Lasserson2020), despite evidence to suggest that carers of people with dementia feel that they can benefit from knowing what the future holds (Crawley et al., Reference Crawley, Moore, Vickerstaff, Fisher, Cooper and Sampson2022). Even the difficult experience of acting as an attorney for a relative with no advance care plan can be insufficient motivation for carers to make their own advance plans (Kermel Schiffman and Werner, Reference Kermel Schiffman and Werner2021). Furthermore, when people do want to have conversations about advance care planning, opportunities can be missed because there are no formalised processes to share wishes, or people make assumptions that professionals already know what they want (Towsley et al., Reference Towsley, Hirschman and Madden2015).

The evidence is therefore mixed, with some demonstrating that people in later life, and their families, do engage with planning about legal and financial issues, and that a diagnosis of dementia can foreshorten people's views of the future, which, in theory, could encourage active planning. But there are also barriers to planning and limited evidence that people do, in practice, engage in activities such as advance care planning. There is even less evidence that people with dementia and their carers engage actively in planning to find and fund social care, should they be ineligible for state support.

Here we address the gap in knowledge about if, or how, people recently diagnosed with dementia, and their family carers, engage with planning for social care and its costs. The paper considers people's attitudes to planning for (potentially) self-funded care, and what facilitates or hinders acting on such plans.

Methods

This paper reports findings from qualitative interviews with selected participants taking part in the DETERMIND programme (Farina et al., Reference Farina, Hicks, Baxter, Birks, Brayne, Dangoor, Dixon, Harris, Hu, Knapp, Miles, Perach, Read, Robinson, Rusted, Stewart, Thomas, Wittenberg and Banerjee2020). DETERMIND explores determinants of quality of life, care and costs, and the consequences of inequalities and inequities for people with dementia and their carers. A cohort of over 900 people diagnosed with dementia within the previous six months has been recruited across three sites in England. Recruitment took place from 2019 to 2023 and included people with dementia and their unpaid carers. The cohort is being followed up annually at least twice, depending on year of recruitment, completing a battery of questionnaires on each occasion.

This paper reports on embedded longitudinal qualitative research undertaken for Workstream 4 of DETERMIND investigating the experiences of social care self-funders and (potential) self-funders.

The sample

Recruitment of the sample for this qualitative strand within DETERMIND is ongoing and being built over time. The purpose is to create a picture of participants' experiences of self-funded social care over three or more years. Baseline descriptive data from the wider study are used to select purposively participants who (a) are already using social care and support or (b) appear likely to be self-funding care they need in the future. This enables a comparison over time of people who are state- and self-funded, and those who do and do not have current care needs. The sample is dynamic; new people are recruited, people already interviewed are re-interviewed, people drop out of the study, others are interviewed only once. This is the nature of qualitative longitudinal research, during which the participants' stories and thus topics of interest develop over time (Neale and Crow, Reference Neale and Crow2018).

The initial interviews included in this paper were undertaken over a two-year period from 2020 and follow-up interviews were undertaken in 2021 and 2022.

Data collection

People with dementia and/or their carer were interviewed face-to-face, online or over the telephone (depending on personal preference and social distancing rules during the COVID-19 pandemic) by one of three researchers. Interviews lasted approximately one hour. Each interview followed a topic guide, but the ordering of topics and depth of answers varied according to the participants' situations. Topics included current care and support, planning and co-ordinating care, paying for care, expectations and planning for the future. Second interviews followed up on events and situations discussed in first interviews. Therefore, second interviews covered different aspects of people's experiences, depending on the nature and progress of people's dementia and their personal situations. Wherever possible, the same researcher conducted first and follow-up interviews to give continuity and aid rapport, which can be a benefit of longitudinal qualitative research (Nevedal et al., Reference Nevedal, Ayalon and Briller2019). All interviewees were prompted to discuss plans for future care and the financial implications of care in each interview. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Data were analysed thematically, guided by Rubin and Rubin (Reference Rubin and Rubin2012), to draw together patterns in the data to help understand the relationship between a diagnosis of dementia and planning for self-funded care. The aim of our analysis was to understand the expressed realities of a range of people newly diagnosed with dementia and/or their carers, and to categorise these into common themes. Each of the authors has research and personal experience of dementia and/or self-funded care for older people. Throughout the analysis, the authors reflected on these experiences and how they affected discussion of key themes.

Data were managed using the qualitative data management software NVivo 12 (QSR International, Melbourne). Large sections of transcripts were coded initially according to overarching topics of interest to the DETERMIND study. This high-level coding enabled the grouping of data from first and second interviews into common themes. This was important as the range of experiences people discussed in first and second interviews overlapped. For example, some people in their first interview discussed a major transition and associated financial considerations such as a move to a care home whilst others, in a second interview, spoke about limited need for care and support. Thus, the date of interviews and whether people were interviewed once or twice was of less importance than the timing in relation to the progression of the dementia and associated events.

For the purposes of this paper, data coded under the high-level codes associated with decision-making, planning for the future and financial issues were reviewed by KB to understand what shaped people's planning (or absence of planning) around paid-for care. After careful reading of the extracts, the data were re-assigned to the following (new) codes: care plans, financial plans, reasons for plans, attitudes to planning, and awareness of diagnosis and implications. Each code contained sub-codes including, for example, positive/negative, facilitator/hindrance, short/long term. Through reviewing these codes and coded segments, key themes (patterns of meaning or experience) were developed and refined in consultation with co-authors.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the DETERMIND programme was obtained by the HRA Brighton and Sussex Research Ethics Committee. People included in the qualitative sample for this paper all had the capacity to give informed consent to take part. Carers were interviewed in their own right (about their own views and experiences) rather than as consultees or proxies for people with dementia. In follow-up interviews, interviewers checked ongoing consent with participants and were careful to consider verbal and visual clues from people with dementia that might suggest a change in capacity. Interviewers were sensitive to people with dementia's feelings about their diagnosis, using the term ‘problems with memory’ rather than dementia if preferred. Where possible, the same interviewer carried out initial and follow-up interviews.

Findings

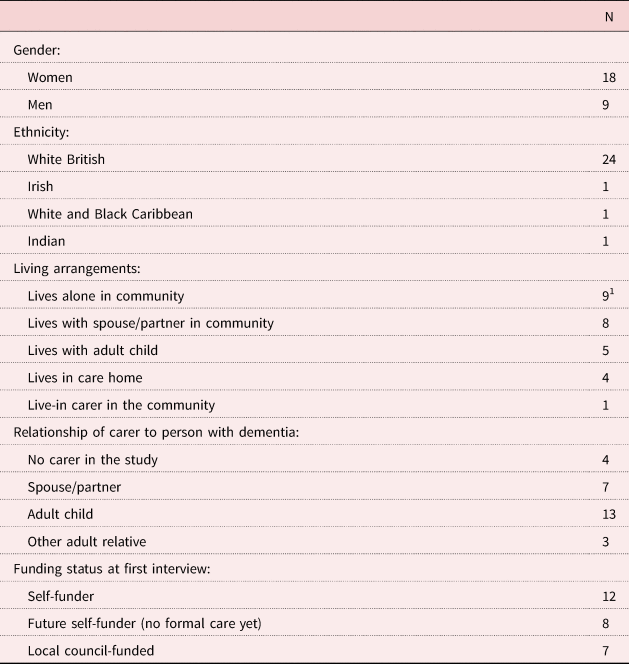

The sample at the time of analysis for this paper comprised 39 interviews relating to the situations of 27 people living with dementia. Table 1 provides the demographics and related characteristics of these 27 people. All were aged over 65 years and lived in the three DETERMIND study regions of London, north-east England and south-east England.

Table 1. Characteristics of people with dementia

Notes: N = 27. 1. Two people with dementia moved to a care home between their first and second interviews.

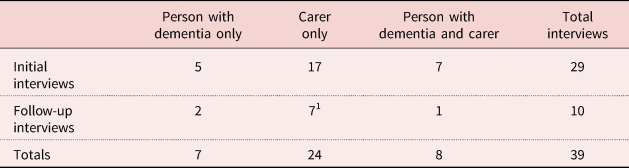

Ten follow-up interviews were undertaken approximately a year after the initial interview. Not all 27 cases were suitable for follow-up by 2022 due to the impact of recruitment delays due to COVID-19, the ongoing nature of sample recruitment (12 months had not passed for all at the time of analysis), participant deaths and dropout from the wider study. Table 2 gives the number of interviews and interviewees. The majority (N = 23) of interviewees were carers. Eighteen were female. In all but one case, the same person took part in the initial and follow-up interviews. In that one case, the person with dementia took part in a first interview and their niece took part in the follow-up interview (because the person with dementia no longer had capacity to consent).

Table 2. Number of interviews

Note: 1. Includes one carer who did not take part in an initial interview.

Our findings indicate that whilst people recognised likely future care needs and their financial implications, this knowledge did not necessarily translate into actively planning for care or thinking about what it may cost. A key reason that recognition did not translate into action was uncertainty. Findings are presented under the following themes: recognising future care needs and financial implications, the role of uncertainty, and drivers of action.

Recognising future care needs and financial implications

Some people were more willing than others to talk about the future, but it was evident that participants on the whole recognised the progressive nature of dementia and expected deterioration over time:

We don't have our head in the sand … people with dementia have plateaus and then it changes. (Carer A01)

This awareness of the progression of dementia translated into a recognition of the potential for increased care needs, in response to changes in both physical and cognitive abilities. Some people stated clear lifestyle-related preferences such as wanting to stay in their own homes or not wanting to be a burden on family. People also spoke about doing well now but seeing a time when they, or the person they cared for, would need additional care and support. Support was discussed in terms of the amount and location of care, as well as who would provide the care, but typically as something to consider at some unspecified point in the future:

I have actually got a very busy life and I'm very grateful that I'm able, I'm not complaining, however I do see that, you know, down the track I am going to need more physical help. (Person with dementia B01) (emphasis added)

I suppose with the Alzheimer's you know that at some point she probably will, well she will need more care and whether that be home-based care or in a care home, you know, that's your choice later down the line. (Carer A02) (emphasis added)

Many had taken legal advice and acted in readiness for a time when they were unable to make decisions for themselves, for example updating wills, changing home ownership from joint tenancy to tenants in common, and setting up LPA. However, when people talked about the potential financial impact of future care needs, it was frequently framed in terms of concerns. Concerns expressed by adult children whose parents lived with dementia typically stemmed from the worry of not knowing whether their parents' money would be sufficient to cover care:

When they [the home care company] put their fees up, you kinda look at it and you think okay, and how much is that gonna cost me every month? So then I go away and work it out, look at mum's incomings and outgoings, what's going up and down, just to make sure that she's not passing that line… (Carer A01)

Worries were exacerbated by not knowing how long care might be needed or what level of care would be necessary. While most carers who were adult children spoke in general terms about the impact on their parents' finances, occasionally they spoke about the impact on their own circumstances. For example, a woman who lived with her husband in an annex attached to her parents' property was concerned that her parents' future needs for care might impact her own living arrangements:

what we're worried about is if my parents, any, if my mum and dad had to go into a care home we'd have to sell the bungalow, which is attached to the annex, and then we'd be homeless ourselves. (Carer B02)

While this couple had not investigated whether their concerns were warranted, others had made enquiries that had set their minds at rest and enabled them to speak with confidence about the affordability of the care and support they were considering. For example, the daughter of one woman with dementia said she had ‘done the sums’ (A01) and was comfortable that her mother could afford to pay for care for four to five years. Similarly, a husband whose wife had dementia had alleviated his worries about the affordability of future home adaptations by investigating costs online.

But others preferred not to think too much about the future costs of care and demonstrated an ostensibly relaxed attitude of ‘what will be will be’. This group talked instead about taking each day at a time or living (and spending) for the present:

I wouldn't scrimp now to think she's got to fund a care home. So I wouldn't, I would be willing to spend what I need to spend as I go. Because nobody can see the future. She could be in a care home a year, she could be in a care home, you know, eight years. You just, you can't, you don't know, so you have to go with what is necessary at that time. (Carer A02)

She hasn't got a lot, and while she's in care she could live for quite a few years, we hope, and the money will just go down and down, and when it's gone, it's gone. (Carer C05)

People were aware that the progression of the condition might affect need for care in the future, and that this could have a financial impact, including running out of money to fund care. However, despite this, people did not readily move beyond recognition to discussing implications, such as limited funds affecting future care choices or necessitating a move to a cheaper care home. The implication was that there were too few certainties to be able to translate knowledge about condition progression into active planning.

The role of uncertainty in planning for self-funded care

The level of uncertainty that people felt about a future with dementia had a strong influence on whether or not they had started to plan actively for care and its costs. Analysis suggested three reasons why uncertainty led to inaction: (a) the belief that care needs would remain manageable; (b) concerns about the longevity of plans; and (c) worries about personal skills, knowledge and capacity to make appropriate decisions.

The belief that care needs will remain manageable

A common reason for not making plans for the future was the hope that the need for formal care would never arise. People were optimistic that the progression of their, or their relative's, dementia would be so slow that if formal care was needed, it would be so far into the future that planning now would be futile. People struggled to imagine what they considered was a hypothetical situation at an unspecified time where the level, type and costs of care were as yet unknown:

I do feel very protective when [husband with dementia] is being asked [about future needs], and frightened at the same time, so yeah … Because [questions about needs] seem to indicate something much further down the line … We, we don't, we don't know how far down the line or what's gonna happen do we? (Joint interview C06)

I'm not sure how you can plan ahead in as much as you don't know when or where, you know, the situation will arise. (Person with dementia C07)

In many cases, the person with dementia was not yet prepared to accept help, and carers were unwilling to impose change on them without their agreement or if their wishes were not known. The following quote is from a woman whose husband with dementia had had a recent episode as an inpatient:

[The hospital] said ‘Do you want him to come home or do you want, want us to put him straight into care?’ And I said ‘I, I can't just do that to him, let him just never come home again’ you know. And he was more knowing then; I mean he still, you know, he still, we still have conversations now, but I just couldn't do it at that time and nothing came of it, he came home and seemed to be coping. (Carer A03)

Whilst this carer felt her husband was still ‘coping’ at home, there were numerous examples of carers describing care and support that was failing to meet the person with dementia's needs, often putting additional pressure on the family to provide informal care, but those same carers generally still felt that the time to make changes was at some unspecified point in the future. People were dealing with difficult trade-offs such as their own wellbeing and ability to provide unpaid care against the person's desire to stay at home, or their capacity to pay for or provide unpaid care now against a backdrop of concern about running out of money to fund care in the future. At the same time, the motivation to make plans to safeguard future finances was weak, as people hoped that the anticipated future might never happen. As a result, people showed little interest in finances beyond the immediate future. The focus appeared for most to be on paying for appropriate care in the here and now.

Prioritising the present was also in part due to difficulties in reconciling the person with dementia's independence now with the likelihood of increased dependence in the future. This resulted in people with dementia deliberately not engaging with future planning. Even where people talked about preferences for the future, this was countered by statements along the lines of ‘I'm not thinking about that but…’:

I haven't thought about that but if I, if I need it I, I wouldn't want to be a burden on my family, I would want to be able to look after myself, with support from someone. (Person with dementia B03)

I've not wanted to engage with all of that [planning for care], and I hold the belief that at the moment it will need to, it will happen. (Joint interview C06)

Thus, the combination of hope for the future and feeling unready to seek help led people to delay taking action.

Concerns over the longevity of plans

While hoping that care needs would develop slowly and far into the future, people simultaneously described a conflicting narrative about the progressive nature of dementia making them feel that as quickly as they were making plans or changes to care and support, those needs changed, making the arrangements redundant. Essentially, people were of the view that there was no point in planning too far ahead because the future was so uncertain that any plans may become irrelevant and thus be wasted effort. Unforeseen changes in the progress of the dementia could hamper long-term plans, as one woman who was a carer for her husband with dementia described. They had recently downsized and adapted a house they hoped would be suitable for the husband's physical needs for around five years, but his needs had since changed more quickly than expected:

I'm not sure that I've actually come to, that I've got a definite plan. I had this house plan, as I've just described to you, I had, I had that sort of plan anyway. I was thinking probably it would be maybe five years before I have to implement that plan. Last year I was thinking that, when we moved. Now I'm not so sure. (Carer C08)

The progressive nature of dementia, which resulted in increasing care and support needs, was described as disruptive and disorientating for the person with dementia, but it also raised a dilemma for carers. The dilemma was choosing the best time to implement changes. Carers were aware that as the dementia progressed and cognitive abilities declined, making changes in care arrangements would become more difficult. But if the person with dementia was content with their current arrangements and had built good relationships with care workers, the temptation was to delay any changes, even though they might be considered as future proofing in terms of both care and finances. It is also possible that carers (perhaps implicitly) delayed changes until a crisis point, when there was no longer a choice, or the person with dementia was no longer able to engage. This could be especially appealing given the uncertainty about whether the need for change would ever arise. The first quote below is from a niece considering the long-term affordability of a care home for her uncle with dementia; the second is from a daughter who had some concerns about the current home care arrangements:

Friends and relatives of [person with dementia] have made the decision that we don't want to move him [to a less-expensive care home] because it would be confusing. And even though he's confused about where he is a lot of the time, essentially he's quite happy and he, we're satisfied that he's being well cared for and, you know, he's in fairly good physical health in there. (Carer B04)

At the end of the day it's got to be what's right for me mum, and me mum is happy with her particular carer at this moment in and if I start chopping and changing carers again when mum's Alzheimer's is actually getting worse then I've, you know, I've got to take a lot of other things into consideration. (Carer C08)

Furthermore, where the person with dementia's health was in a period of flux, including comorbidities unrelated to dementia, carers were reluctant to instigate any plans until they knew if and to what extent the person with dementia might regain functionality or their care needs may stabilise. This daughter describes her feelings when trying to plan around multiple fluctuations in her mother's care needs:

There's been three other times I've been at her bedside, liver failure, where they thought she's not going to survive. Every time she's come back … I've just realised that there's no point in really sort of planning, because it's just like – it did change all the time … it was just doing my head in. So I just think, I'll just take it as it is, and unless there's – we'll deal with whatever happens when it happens, kind of thing. Because the pre-planning is not worth it. Things always change. (Carer A04)

Balancing care, finances and other commitments during these periods was particularly stressful.

Uncertainty about skills, knowledge and the capacity to act

People spoke about their lack of confidence in their own skills or knowledge, which led them to delay planning or taking action. For example, carers worried about not knowing the costs of care or the financial implications. People did not know if the time was right for their relatives with dementia to move to a care home, or what type of care home would be suitable for their immediate needs and remain suitable in the longer term. People did not understand the financing of care, the cost of advice or what would happen if the money ran out. Some were reluctant to seek financial advice about paying for care because they found discussing finances intimidating:

My mother, it's difficult cos she doesn't actually need nursing but she's probably not good [well] enough for a care home; I'm not quite sure how, where the line goes really. (Carer C04)

[Paying for care is] the one bit I've not properly engaged with and I don't feel like doing it, first of all cos part of me thinks well we'll deal with it when we get there, and the other bit is that I've never understood all that stuff anyway. I'm not very comfortable with all that kinda stuff, my talents lie elsewhere. (Person with dementia C06)

So it's difficult really to think ‘oh well if I do that…’, but then in four years' time what happens, or five years, whenever the money runs out. But, but that, that's sort of what, a self-funding question mark that, you know, you don't really have an answer to until you get to that point… (Carer A02)

Many people, despite holding strong views about their preferences for the future, did little to help make those preferences a reality. For some, the perceived effort or potential negative consequences of implementing a change appeared to outweigh the benefits. In particular, people spoke about their hesitancy in selling family homes or preparing them for rental to enable downsizing or freeing up of funds to pay care fees. Part of the reluctance was attachment to the family home but for adult children of people with dementia this was exacerbated by their capacity to act due to the busyness of their lives, often caring for families and working as well as navigating the social care system. Processes that should be simple, like filling in application forms for care-related benefits and discounts, put people off acting because they were too complicated or time-consuming.

Reasons for action

Few people discussed factors that facilitated planning, but there were some exceptions where the dementia diagnosis had prompted families to gather knowledge or actively plan. A common thread across participants' views was that this propensity to plan reflected people's characters as ‘planners’. Occasionally, and in contrast, external triggers were the prompt.

Being a planner

People who described themselves as planners spoke about taking one step at a time or getting gradually sorted with respect to future care and finances. For these self-defined planners, the potential costs of care and making financial arrangements in anticipation of change, especially to maintain preferred living arrangements, were important:

With the financial consultant it was more about how we could make her money last as long as possible, you know, cos we didn't know at that point whether she would be able to manage independently having, you know, and being in the wheelchair. So we, I mean as it is, as I said, because of the determination, she, that's where she wants to be, at home, and she wants to do everything she possibly can to make sure she can stay there. (Carer C01)

In some cases it was the person with dementia who was the planner, previously expressing a preference, such as not to be a burden on family, which effectively gave families permission to plan for that eventuality:

Our mother's always planned ahead. She likes the flat she lives in now. She had been living in a house with a garden and she thought – and she loves gardening – ‘I'm not always going to be able to manage the garden’, so before she got to the point where she couldn't, she moved. She's very practical, and I think it's rubbed off on us. (Carer C02)

People also spoke about how their past experiences, some care-related but others not, prompted them to plan. These included positive experiences, whereby people would repeat earlier actions that had worked, as well as negative experiences or inaction that led to a crisis that people wanted to avoid repeating. For example, one woman learnt from her friend's experience and bought a care-related financial product, as described below:

She's an intelligent lady and I think before she had dementia she realised that living alone, without children and so on, she may well need to pay for care at some point or other. I think, some years ago, I took out an insurance policy for my father and she was aware that that paid out really well and was really helpful to us and she decided to, to follow suit. (Carer C03)

Another woman, who had experienced her husband's very high self-funded care costs some years earlier, had put her house into trust for her grandchildren years before her diagnosis of dementia. Thus, being a planner could play out in multiple ways.

External triggers

Occasionally, external factors prompted people into action. This was evident particularly in relation to substantial financial decisions. For example, a daughter described slowly ‘muddling through’ (Carer C04) the decision that her mother should move into a care home, but realising quite quickly that she had to sell her mother's house when it became apparent that without doing so the fees were not affordable in the long term. A niece acting for her uncle with dementia, who had previously taken out equity release loans against the value of his home (unrelated to care), was left with no choice but to sell his house to repay the loans when her uncle moved into a care home. Neither family had planned for these events, although it could be argued that both were foreseeable, even if the timing of them was not. Other examples included carers needing operations or going on holiday, which prompted the need to pay for additional temporary care for the person with dementia.

Discussion

The analyses reported here set out to consider how a diagnosis of dementia affected people's planning for self-funded social care. The expectation was that the increased chances of needing care would motivate people to plan for the costs of care. The findings show that, in this sample, people with dementia and their carers recognised the progressive nature of dementia and its potential impact on future care needs. They also had preferences about their future, in particular about living arrangements. However, despite having concerns about the financial impact and long-term affordability of self-funded care, people did not routinely take actions to ensure their care and accommodation preferences could be realised. Instead, they hoped that they would not need care and so did not engage with planning to pay for it.

A common theme linking the reasons for people not actively planning was uncertainty. Uncertainty is different from risk. Risks are known and can be planned for. Uncertainty is about the unknown. Our expectation was that a diagnosis of dementia, and thus a high likelihood of eventually needing care, would provide people with a degree of certainty on which they could base their planning for self-funded care. People with dementia and their carers felt almost universally that the future was uncertain, confirming recent findings by Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Manthorpe, Samsi, Abley, Robinson, Watts, Bond and Keady2016). That is not to say that they failed to understand or accept that needs would increase (although they hoped they would not), but they felt that uncertainty about the extent, timing and financial impact of care needs outweighed the certainty of declining independence brought about by the diagnosis. Despite evident worries about the affordability of care, people felt that their futures, or those of the people living with dementia that they cared for, were so uncertain that they typically focused on the present. It is possible that the unpleasant prospect of cognitive and physical decline that would precipitate a need for care also led to participants emphasising their present abilities and the uncertainty of the future. This chimes with findings from earlier studies that people, with or without dementia, live for the present and avoid thinking about a future that is both uncertain and unappealing (Hellström and Torres, Reference Hellström and Torres2016; Heavey et al., Reference Heavey, Baxter and Birks2019; Crawley et al., Reference Crawley, Moore, Vickerstaff, Fisher, Cooper and Sampson2022; Thuesen and Graff, Reference Thuesen and Graff2022). The findings also confirmed research that people are uncertain about their skills and knowledge for making appropriate decisions or seeking relevant advice (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Heavey and Birks2018, Reference Baxter, Wilberforce and Birks2020b), and this uncertainty can lead to hesitancy. The diagnosis of dementia and its follow-up presents a possibility for professionals to engage with family uncertainty and help move from inaction to action, but such opportunities are seldom offered with no clear ownership of this support role (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Dickinson, Bamford, Clark, Hughes and Exley2013).

A second theme was timing, which was evident in a number of ways. People felt that the effort of planning now would outweigh any future expected benefit of decisions about paying for care and so they delayed decisions. This perception is also linked to the uncertainty discussed above; spending time and energy planning for something (in this case, self-funded care) that may not happen can be seen as fruitless. It may also limit people's future options by closing certain avenues. For example, people may be concerned that once financial decisions have been made (such as selling the family home to release funds for care) they cannot be reversed. Lemos Dekker and Bolt (Reference Lemos Dekker and Bolt2022) discuss this in relation to advance care planning; they call it a paradox of control – taking control now by putting in place plans for the future means losing control over the future. The question is whether money is different from care. A decision not to plan now for future care does not necessarily rule out any options; if additional or a different form of care is needed, decisions can be made later. But as personal finances are limited, a decision not to plan now for funding care in the future means that those resources may be spent on other things and so no longer be available for funding care. In the extreme, spending money on care in the present without considering the future could result in the depletion of resources and therefore loss of control over future care and funding decisions.

However, despite concerns about expected future benefits, people in this sample talked about how their previous (positive and negative) experiences of paying for care affected their current decisions. These experiences appeared to make people think differently about the impacts of not acting, even though the future was still seen as uncertain. For example, the people in our sample who had, or knew of others who had, experienced what they considered substantial care costs in the past felt prompted to make decisions to avoid those situations themselves. In effect, these experiences tipped the balance in favour of acting. This is in contrast to Kermel Schiffman and Werner's (Reference Kermel Schiffman and Werner2021) finding that carers chose not to make advance care plans for themselves even after negative experiences of making decisions for relatives without an advance care plan. The difference may be due to finances and people's fear of ‘losing’ their savings. There is a literature about anticipated regret that sheds light on this.

Anticipated regret is a negative feeling that people have at the time of making a decision if they think they may regret that decision in the future (Brewer et al., Reference Brewer, DeFrank and Gilkey2016; Kermel Schiffman and Werner, Reference Kermel Schiffman and Werner2021). Many care-related decisions are difficult and people feel or anticipate feeling regret; housing decisions and location of care are examples (Garvelink et al., Reference Garvelink, Ngangue, Adekpedjou, Diouf, Goh, Blair and Légaré2016; Lognon et al., Reference Lognon, Gogovor, Plourde, Holyoke, Lai, Aubin, Kastner, Canfield, Beleno, Stacey, Rivest and Légaré2022). Decisions, as discussed above, may involve doing something or doing nothing. Both can induce anticipated regret. Anticipated regret from doing something (action regret) can discourage behaviour (Brewer et al., Reference Brewer, DeFrank and Gilkey2016) as people fear the consequences of their decision. Our findings support this; people were anticipating making decisions that may need to be changed or would not be relevant, and so may at best result in wasted effort and at worst be costly and/or shoehorn people into paths they could not change and may regret. Brewer et al. (Reference Brewer, DeFrank and Gilkey2016), in their meta-analysis of anticipated regret and health behaviour, found anticipated inaction regret was felt more strongly than action regret. In other words, people felt more responsible for inaction than action. The authors explained inaction as defying medical authority (e.g. to have a vaccination), leaving the decision-maker open to self-blame. But for self-funded social care there is often no authority advising what course of action to take. The exception would be people who had a needs assessment or guidance on appropriate care and support; this is rare for self-funders (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Heavey and Birks2020a). It follows in this context then that inaction becomes the most blameless thing to do.

Finally, timing was important because people with dementia expressed a preference to manage without formal, paid-for care. They wished to maintain their current situations for as long as possible and some spoke about actively avoiding thinking about the future, as found by Hellström and Torres (Reference Hellström and Torres2016). Carers were typically not willing to impose self-funded care or changes in living arrangements on the person with dementia without that person's agreement, but deciding on the right time to obtain this agreement was not easy. Heaton et al. (Reference Heaton, Martyr, Nelis, Marková, Morris, Roth, Woods and Clare2021), in their secondary analysis of experiences of people with dementia and their carers, similarly concluded that it was perceived to be either too soon or too late to make changes. That is, either the person with dementia was not ready for change or their carer felt that their condition had progressed too far and that change would be too disruptive.

Strengths and limitations

This analysis is based on 39 in-depth interviews about the care, support and future plans for 27 people with dementia. Almost half the sample comprised people who were currently self-funding their social care, with the remainder divided equally between those who expected to pay for care in the future and those receiving local council-funded care. This reflected the focus of the research but does not necessarily reflect the wider population of people with dementia and their carers.

The majority of interviews were with carers. There were only five initial and two follow-up interviews where the person with dementia was interviewed and a carer was not. Interviews with carers were longer and more detailed than interviews with people with dementia. Thus, the analysis is weighted towards the views of carers. It was not possible to discern any differences in how people with dementia and carers viewed or experienced planning for self-funded care from the interview data collected. While this is a limitation, the reality is that carers undertake much of the decision-making for or with the person they care for, especially as care needs progress. Where there were differences in experiences or the preferences expressed, these have been included. Furthermore, if care and funding decisions are not taken early, delayed instead until the person with dementia is no longer able to play a meaningful role, it is the carers who take the lead. Thus, understanding carers' views on planning is crucial.

Implications for practice

Our findings show that, in this sample, people with dementia and their carers largely do not wish to engage in thinking about a future of self-funded care or planning for that eventuality. Yet they do have views about how they want their future to be lived, in particular about where they wish to reside. Failing to make care and financial decisions while they are able may jeopardise these preferences. The way in which people spoke about decisions being unnecessary until things changed, or chose not to think beyond a point where funds for self-funding care were depleted, suggests a degree of naivety about the social care system and the complexity of making care and funding decisions. When people's money runs out or their care needs change, the process of re-arranging care takes time and involves a range of professionals as well as family; necessity and urgency may limit choices at this point.

The task for those involved in the care of people with dementia in the heath and adult social care sectors is therefore to identify the points and places in the system where worries about future self-funded care can be addressed, and carers and the people they care for can be prompted and supported to act. There is a lack of programmed help and support, and little work to ensure that professionals feel confident and competent to undertake such sensitive and potentially distressing discussions. This leads to the perception that providing such support is somebody else's role. Opportunities could also be sought to help people understand the benefits of financial guidance or advice to maintain preferred self-funded care choices for as long as feasible. The effect of not helping people to plan is that carers inherit the decision-making role if the person with dementia becomes unable to participate, and they may have to make decisions in the absence of clear preferences from the person with dementia. Towsley et al. (Reference Towsley, Hirschman and Madden2015) found many people wanted to be asked about advance care plans but there were missed opportunities because of a lack of formalised processes. The same appears to be true for self-funded social care. All people with potential care needs are entitled to an assessment by the adult social care section of their local council, but self-funders often do not approach their council for help, or report being signposted elsewhere when it becomes apparent they will be self-funders (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Heavey and Birks2017). Opportunities need to be created within the system to think about the self-funding journey for people with dementia and consider who is best placed to raise these issues, and when. Lessons about moving to more active planning might be learned from the palliative care context where, though a very different situation from self-funded social care for people with dementia, national policies aim to promote care from the point of diagnosis (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2019).

A review of evidence on the impact of public messaging about palliative care, advance care planning and hospices found that public-facing messaging focused on death and dying, albeit ‘a good death’ (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Back and Dettmar2021). However, the review concluded that as people are generally reluctant to talk about death and dying, this messaging failed to encourage people to talk about, or actively plan for, these types of care, even though their awareness was high. People are similarly reluctant to talk about personal finances and may not want to think about having to depend upon care services in the future (Gunnarsson, Reference Gunnarsson2009). In England, government plans for social care funding changes have received much public attention, meaning that people are aware of the possibility of depleting resources to pay for care. Changing the messaging from avoiding ‘catastrophic costs’ (Warren, Reference Warren2022) to the more positive prospect of managing funds to maintain preferred care options could be one way to encourage more active engagement.

Financial support

The DETERMIND study was supported by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (grant number ES/S010351/1; ‘Determinants of quality of life, care and costs, and consequences of inequalities in people with dementia and their carers’; investigators: S. Banerjee, K. Baxter, Y. Birks, C. Brayne, M. Dangoor, J. Dixon, P. Harris, B. Hu, M. Knapp, S. Read, L. Robinson, J. Rusted, R. Stewart, A. Thomas and R. Wittenberg). The support of the ESRC and NIHR is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval for the DETERMIND programme was obtained by the HRA Brighton and Sussex Research Ethics Committee (REC 19/LO/0528. IRAS 261263).