Introduction

Ever more people are working past pension age (Adolphson, Reference Adolphson2015; Lain and Loretto, Reference Lain and Loretto2016). In Sweden, despite a mandatory retirement age of 67, tax records from 2016 show that one-tenth of 77-year-olds had a job (Alecta, 2019). Most studies envision the older worker as somebody aged 50–64; little qualitative research has examined the paid labour of workers older than pensionable age. This often overlooked group of workers has broken the old-age pension–retirement lockstep, destandardising the three-phase model of the lifecourse in a singular way. In this paper, we will argue that the experience of working at ages older than typical ages of eligibility for old-age pensions is distinctive enough to form a new career phase.

Retirement, the lifecourse and the third age

Retirement as a lifestage emerged over the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century (Kohli and Rein, Reference Kohli, Rein, Kohli, Rein, Guillemard and van Gunsteren1991). Seeking to tackle old-age poverty and mass unemployment, governments set up pension schemes and allowed employers to retire older workers once they were eligible for old-age pension payments. Retirement became a taken-for-granted feature of the tripartite lifecourse and old age became synonymous with retirement lifestyles (Kohli, Reference Kohli and Marshall1986). Following second-age career and family-building responsibilities, the financial security and free time provided in retirement offered the promise of a new phase of life – the third age – when retired people could devote themselves to fulfilling their personal goals (Laslett, Reference Laslett1987). But only as long as health and vigour held; these years of personal achievement would be terminated by a fourth age of ‘dependence, decrepitude and death’.

In recent years, as age-graded policies, practices and cultural beliefs unravel, the lifecourse has been destandardised to some degree. Institutionalised passages within the normative lockstep lifecourse from education to employment to retirement have become ‘do-it-yourself’ projects (Moen, Reference Moen, Carr and Komp2011). Old-age insurance and pension systems no longer manage cliff-edge retirement transitions out of the labour force, instead individuals, as far as they are able to, make strategic selections to chart their lifecourses. For increasing numbers, the passage from full-time work to full-time leisure has become a process involving one or more stops for bridge jobs that are often part-time (Cahill and Quinn, Reference Cahill and Quinn2020).

While retirement offers a certain sort of liberty, freeing people from economic dependence on the labour market and from the restrictions of the workplace, it also deprives people of possibilities. One aspect is financial: pensioners face life on a fixed income and a lower living standard (Estes, Reference Estes, Minkler and Estes1999). Another aspect is occupational deprivation: the social institution of retirement enforces inactivity, lessened social status and social withdrawal (Whiteford, Reference Whiteford2000). One could question, as Gilleard and Higgs (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2005: 2) do, whether retirement actually ‘represents quite the position of agency that is often claimed for it’. From this perspective, keeping on some work while pension claiming might let older adults square the circle. While benefiting from the freedom provided by pensions, participation in the labour market would help older adults remain active consumers, maintain their position in society, and continue to engage in enjoyable and meaningful activities.

A potentially radical vision is offered by ‘encore’ adulthood, a career stage encompassing people in their fifties, sixties and seventies. Encore adulthood views the late career as an improvisational lifestage with its own risks and possibilities, which takes place against a background of lagging institutional contexts encouraging withdrawal from the workforce (Moen, Reference Moen2016: 29). It accommodates the fact that older people may not intend to exit from the workforce, even after attaining pensionable age (Moen, Reference Moen2016: 114). By working into the latter part of the late career, the retirement years, individuals decouple the pension claiming–retirement lockstep. Paid work in the retirement years provides a glimpse of a less-restrictive vision of the third age, one that may include paid work (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson, Minkler and Estes1999). These theoretical developments let one ask, what does paid work in the latter part of the late career look like? Might paid work in the retirement years provide a way for people who are not ‘consummate’ individuals to blend the second and third ages (Laslett, Reference Laslett1987)? These ideas lay the groundwork for empirical examination of paid work in the late late career as a subject of central interest, rather than merely as part of a drawn-out retirement process. The unique circumstances of this lifestage – in which old-age pensions underpin financial security – may shape a new relationship to paid work. We wondered whether these overlooked years might be distinctive enough to demarcate a new career phase (Moen, Reference Moen2016: 28).

Despite these possibilities, empirical studies examining paid work carried out in the latter part of the late career remain scarce, particularly those taking a qualitative perspective. Most qualitative research has focused on the early part of the late career or on plans for continued paid work in retirement, since participants tend to be in their late fifties or early sixties, although small numbers of participants working after pensionable age may appear in samples (Moen, Reference Moen2016). Over the last three decades, a handful of studies have focused on people working after pensionable age; these studies originated from Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (Fréter, Reference Fréter, Kohli, Fréter, Langehennig, Roth, Simoneit and Tregel1993; Wachtler and Wagner, Reference Wachtler and Wagner1997; Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Parry and Taylor2004; Deller and Maxin, Reference Deller and Maxin2008; Lynch, Reference Lynch2012; Hokema, Reference Hokema2016; Wentz and Gyllensten, Reference Wentz and Gyllensten2016; Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Flisbäck and Lund2017). They have generally explored people's motivations for working; examined prerequisites in the work environment for being in work, especially in relation to temporal and task flexibility; and contrasted current work to earlier pre-retirement phases of working life.

Some of this research has drawn on ideas of how work in the retirement years provides opportunities for fulfilment of personal goals in a sense that is related to, but was excluded from, Laslett's conception of the third age. These ideas of individual flourishing lie at the heart of Freedman's (Reference Freedman2008) ‘encore career’, in which this lifestage opens up opportunities for roles with greater meaning and impact. Others have developed the idea of work in these years as a calling, finding that work provides a source of existential meaning (Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Flisbäck and Lund2017). In the current study, we will explore whether work carried out after pensionable age can be described as a calling or whether people relate to their jobs more prosaically.

Paid work in the retirement years

The goal of the present study is to contribute empirically and theoretically to scholarship of the late career by examining the nature of paid work taking place in the retirement years. We focus in particular on the conditions, constraints and consequences of paid work after pensionable age. We describe the context – the retirement years – within which work takes place as well as explore individual interaction strategies in performing this work. In reflecting critically on the findings, we draw together this disparate and multilingual literature about paid work after pensionable age and relate it along with our findings to the theoretical mainstream in social gerontology.

Our analyses of work after pension age are embedded in a broader symbolic context: the experience of a time of life when normative expectations are of a retirement lifestyle, a time we call the ‘retirement years’. Exactly when these years begin is difficult to place because such age boundaries have become fuzzy. Late modern pension systems present individuals with a surfeit of alternatives, a tendency typified in Sweden by its pensionable age band rather than a single pension age. Lacking a single demarcating line, we take a family resemblances approach. Specifically, we define paid work taking place after pensionable age as working at ages when claiming a state old-age pension would be possible, as participation in a bridge job or as working while drawing a pension.

Our source material is interviews with a diverse group of Swedish people in their mid- to late sixties and early seventies, many of whom continued in paid work after the normative retirement age of 65 or took up working again after retiring. Our analytical focus was on paid work; volunteering was treated as an activity outside the scope of this paper because it is distinct from paid work in terms of status, financial remuneration and legislation.

Relevant aspects of the Swedish context

In the 1990s, substantial reforms to the Swedish pensions system removed age 65 as the state pension age in favour of a flexible pensionable age. At the time of our field work, individuals could choose to begin claiming the state earnings-related pension at any time between 61 and 67 years, the size of monthly pension pay-outs being uprated for each year pension claiming was delayed. However, the significance of turning 65 has not entirely disappeared from individual awareness and institutional logics. It is still a norm – albeit weakening – to retire at age 65. This age also marks a shift from working life to old-age social protection systems: unemployment insurance may no longer be claimed; incomes of residents on low pensions are protected by the guarantee pension (Halleröd, Reference Halleröd and Scherger2015). State pensions are supplemented by occupational pensions (held by 70% of pensioners) and private pensions (held by 24% of pensioners) (European Commission, 2018: 80). In 2018, total pensions averaged 17,600 crowns monthly (around €1,730), with state pensions comprising almost three-quarters of these payments (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2021).

While almost no older people experience material deprivation – rates are strikingly lower than nearly all other European Union (EU) countries – at-risk-of-poverty rates for single people ⩾65 years are higher than the EU average (European Commission, 2018: 30–31). Pension expenditure per person ⩾65 years as a share of per capita Gross Domestic Product is close to the EU average (European Commission, 2018: 35). Net replacement rates from mandatory pensions for average earners are under the average for high-income countries at 55 per cent of prior earnings (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017: 107). Women have a greater risk of low pensions – in 2012, women's pensions were worth 66 per cent of men's – as do people who migrated to Sweden in mid-life from outside the European Economic Area (Adolphson, Reference Adolphson2015).

During the field work, the legal mandatory retirement age in Sweden was 67 years. After this age, the employer can decide about further employment and make individual arrangements with employees, such as employing pensioners on an hourly basis (Laun and Palme, Reference Laun and Palme2017). Labour market participation rates of older workers are high: one-quarter of Swedish 70-year-olds paid tax on earnings in 2016 (Alecta, 2019). Participation in paid work after pensionable age has been encouraged by the opportunity to earn income without submitting to reductions in pension income apart from those due to tax on higher earnings. In certain areas, such as health care, personnel shortages encourage employers to consider hiring employees who are older than pension age. While employment rates in Sweden are high, age discrimination in the labour market is a substantial barrier to working in old age (Pensionsåldersutredningen, 2012), particularly negative attitudes towards older people looking for new employment (Carlsson and Eriksson, Reference Carlsson and Eriksson2017).

Methods

Study design

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of paid labour of older workers in Sweden and to develop a theory that explains these processes. Our approach incorporated principles of grounded theory; specifically, we employed concurrent data collection and analysis, theoretical sampling, memo writing and constant comparative analysis in order to develop theory (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2014; Birks and Mills, Reference Birks and Mills2015).

Participants

Nearly all participants were drawn from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH), a multi-year, register-linked biennial follow-up study of several nationally representative samples of working individuals, aged 16–64 years old at inclusion (Magnusson Hanson et al., Reference Magnusson Hanson, Leineweber, Persson, Hyde, Theorell and Westerlund2018). Over 28,000 participants have responded to at least one survey since SLOSH began in 2006. Participants aged in their late sixties and early seventies were eligible for inclusion in the interview survey. Using information from survey and register data, we generated a purposive sample by selecting participants from SLOSH who exhibited varied work and retirement pathways: continued paid work in retirement, unretirement, cliff-edge and gradual retirement. We sampled from these participants for diversity in terms of gender, education level, social class and region, and in order to include foreign-born citizens. Since non-white ethnic minority groups are poorly represented in SLOSH, we recruited via our personal network an interviewee from the Swedish Kurdish population, who was interviewed in Sorani. We interviewed 25 people in 2019: 10 men and 15 women (Table 1). A variety of occupations were represented, including archivist, gardener, mechanic, hairdresser, nursing assistant, electrician and engineer.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

Note: EU: European Union.

Data collection

The face-to-face interviews were carried out using a semi-structured interview guide which was informed by the existing literature and drew on interview guides used in similar research in the UK and Germany (Hokema, Reference Hokema2016; Vickerstaff et al., Reference Vickerstaff, Lain, Crawford, Loretto, Phillipson, Robinson, Shepherd, Wainwright and Weyman2017). It covered current work and other activities, retirement, career history and pensions planning, and was followed by filling in a questionnaire on demographics, working patterns, earnings and pensions. Interviews lasted 50–120 minutes and were audio recorded. DR carried out most of the interviews in collaboration with LGP. A research secretary fully transcribed the Swedish-language interviews; DR translated and transcribed the Sorani interview into Swedish. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and identifying information was removed.

Analysis

Interviews were uploaded into the NVivo 12 program (QSR International, Melbourne) to aid analysis. While interviews were ongoing, initial coding by LGP began. Through data-driven open and focused coding, categories reflecting experiences of paid work in the retirement years were identified. Subsequent axial coding facilitated the explanations of the context, processes, interactions and relationships in those experiences. Areas of higher coding density in the first ten transcripts were translated into English and analysed by AI. Constant comparative analysis based on diversity in the sample was employed to ensure that the emerging codes described the categories in their full complexity. Theoretical saturation was reached at the seventh interview (no new concepts or categories emerged), but we continued to analyse the final 18 transcripts in order to obtain rich descriptions of the categories in our diverse sample. Analytic memos were written throughout data analysis, enabling categories to be described and refined, and to find linkages between codes. The categories were then discussed in a series of analysis meetings between LGP and AI. Emerging themes were refined with the use of mapping techniques to visually arrange and conceptualise the categories, their structures and linkages. Building on limited pre-existing knowledge, we focused in particular on how the core categories and relationships between categories led to a specific experience of paid work for people older than pensionable age. This process led to the development of theory in the form of a running discussion about why the experience of paid work in the retirement years has the nature that it has. Credibility was maintained by sharing data analysis and selected quotes with team members less involved in coding as well as by audience review at the ProWorkNet meeting 2019 in Sigtuna, Sweden.

Results

The retirement years

The age range in the sample was 64–74 years, with an average age of 69 years. Everyone was drawing a pension. Swedish pension rules enabled state pension claiming from 61 years; occupational pensions often can be claimed from younger ages. However, the age markers used by interviewees were 65 and 67 years. The age of 65 had a symbolic force for participants of having for a long time been the state pension age and remaining as the normative pension age. As explained by one participant who was asked about whether they reflected a lot on their decision to retire: ‘No, it was just … once you reach 65 then you retire’ (Rolf, 70, retired mechanic). Participants expressed their retirement timing in relation to this age, such as retiring six months before reaching 65 or retiring in the spring after reaching 65. The legal mandatory retirement age of 67 years featured prominently in the interviews for other reasons; typically employers retired workers who reach this age or placed employees on hourly contracts:

Yes, but well when you have a perm contract, permanent contract, when you have that in the municipality you are only allowed to work until 67. After that there will be other conditions for you to go in and work. But there are people who go in and work. So, when there are certain positions that are hard to fill so they get in touch with retirees if they will go in. (Maria, 68, retired technical assistant)

In Swedish, the term pensionerade has two meanings: drawing a pension or having retired with a pension from a job. Working while pensionerade may involve a new job, new contract, returning to work and/or continuing in the same job with advancing years (and, eventually, for one reason or another, drawing a pension). All in our sample viewed themselves as either retired (pensionerade) to some degree or had, as a point of comparison, similar others who were retired. Although working at this time of life is common enough, and a couple of interviewees noted it becoming more common, it was still perceived by wider society and the interviewees themselves as unusual. One could argue that the paid work that pensioners perform has been invisibilised. This is why we use the term ‘paid work in the retirement years’, to reflect that interviewees were participating in paid work in a phase of life which is set aside for other activities.

The participants tended to have several pension streams: typically state pension, occupational pension and for some private pension. Two participants were receiving supplements to a low pension: guarantee pension or a housing costs subsidy. Out of a potentially complex set of arrangements, following commencement of pension claiming, the size of participants’ incomes had become known, steady and secure. The participants were able to cover their necessary living costs (‘I get by’, in the original (orig.) ‘jag klarar mig’), although several interviewees, particularly women and people who arrived in Sweden in adulthood from countries outside the EU, described their pensions as low. However, for almost all the interviewees, there was little sense that they were worried about an uncertain financial future or fearing financial calamity.

Although finances featured peripherally in most interviewees’ uncertainties, future health and the possibility of dying were central. The interviewees presented the retirement years as a vulnerable and finite state, which would inevitably be terminated by serious illness and death. No one knew how long they would get (orig. ‘får’), since devastating events could happen (orig. ‘händer’) suddenly at any time. Asked what she expected to be doing in five years, Eva (73, after-school teacher) stated, ‘Then I'm nearly 80, then you don't know. Perhaps I am senile, demented and … sit in a wheelchair or … one doesn't know.’ In the face of this threatening, fixed and yet unknowable future, participants employed expressions of hoping and conditionality and rejected a language of knowing (‘I don't know’). They dismissed suggestions by the interviewers to think five years ahead to concentrate on the short time window of the present (‘while I'm’). Rather than taking up the battle with unmanageable fate, the participants’ agentic focus was on living the good life now (orig. ‘njuta av livet’):

Rather however that … you just don't know what will happen in the future. Instead being able to enjoy and live and for things to be ok as long as you can have that. (Barbro, 66, retired administrator)

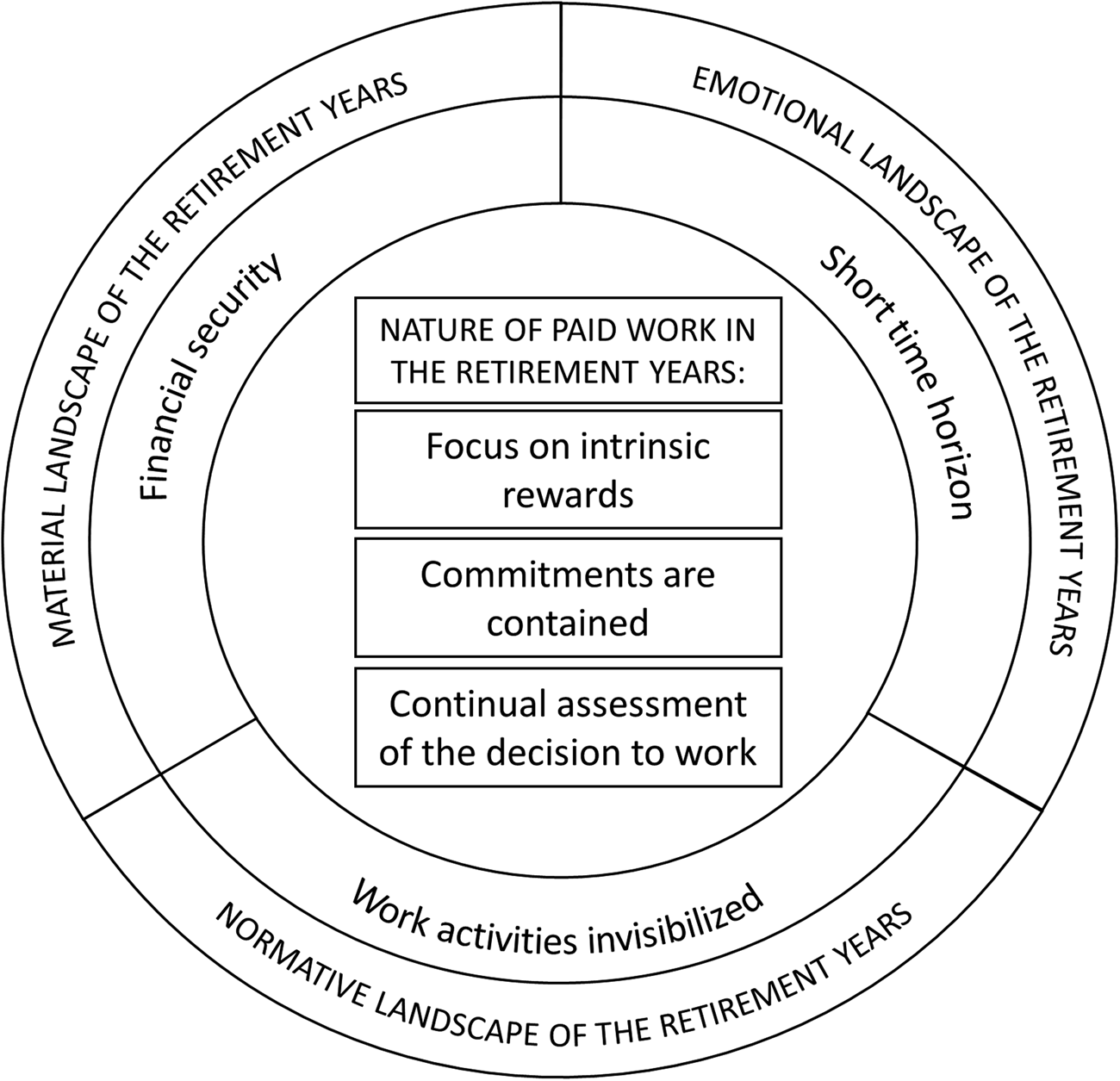

To sum up, the retirement years are characterised by financial surety provided by old-age pension receipt, albeit for some at low levels; by being a phase of life set aside for retirement; and by a sense of contraction of the future. This material, normative and emotional landscape shaped how the participants engaged with the labour market (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The landscape of the retirement years shapes the nature of paid work.

Paid work in the retirement years as a distinctive stage in the late career

In-work participants were generally employed on an hourly basis (timlön) or running their own businesses. The participants’ identities reflected their intermediary position between paid work and retirement (the second and third age), an ambiguous status that participants had to use qualifiers to specify:

So it is a little bit, I am retired or I am not retired. It is a little hard to answer … But I work as a full-time [employee] and I take out my pension. (Ulf, 69, engineer)

But I have worked on an hourly basis at my old job quite a bit… (Gunilla, 68, retired archivist)

Björn: Now I'm a full-time pensioner.

Interviewer: You're a pensioner…

Björn: Although I've been in and worked five days so far this year. (Björn, 67, carpenter)

Our in-work participants were no longer in Laslett's (1987) second age, and yet retained certain characteristics of their working life (work-based social network and activity patterns, earned (higher) income, maintained consumption patterns). That they worked makes it difficult to describe them as third agers, and yet they also had characteristics typical of the third age (others around them are retired, pension receipt, paid work no longer a necessity). By performing paid work in the retirement years, an interplay of the two worlds of work and retirement arose which generated characteristics of its own.

In what follows, we draw out the main attributes of paid work in the retirement years: the intrinsic benefits of job(s) as well as the processes of containing commitments and reassessing the decision to work. We will relate them back to the wider context – how the landscape of the retirement years shapes the distinctive characteristics of these jobs – presented in the theoretical framework (Figure 1).

Intrinsic rewards of paid work

The fulfilment and enjoyment that paid work provided was prominent in the interviews. Since the focus of most research into late-career work has been on its intrinsic rewards (e.g. Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Farrow and Blank2012; Bengs and Stattin, Reference Bengs and Stattin2018), we map out these aspects only briefly here. Frequent characteristics of the jobs were that they: were rewarding (orig. ‘givande’) and meaningful, allowed people to achieve something and to deploy their knowledge and experience, provided a sense of contributing and being needed, and provided sociability and a sense of collegiality and belonging. Some previous research has described paid work in the late career in terms of a ‘calling’ or a ‘new purpose’ (Freedman, Reference Freedman2008; Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Flisbäck and Lund2017); in our sample, work orientations were more humdrum.

The words most often used to describe jobs were ‘fun’ and ‘enjoyable’ (orig. ‘kul’ and ‘roligt’). In her study of interviews from Germany and the UK, Hokema (Reference Hokema2016: 227) argued that this prerequisite for working in the retirement years has been overlooked; we likewise emphasise the importance of ‘fun’ in people's accounts. Work providing a strong source of fulfilment and enjoyment was not confined to managerial or professional jobs. Further, the rewards of work were visible even for jobs that can be psychologically or physically tough, such as working night shifts as a midwife or driving lorry deliveries. A few participants talked passionately about their jobs, in detail and in the most positive terms; we appreciated the challenge they were facing to fill up these job-sized spaces with more traditional retirement interests:

I could have taken my pension a long time ago but I've enjoyed the last 20 years of my life an unbelievable amount, I've been running a business, I have worked with clients that I liked, etc., so if I was single I would have said, I would have kept working until they lay me in the ground, I mean until I die. For I find working really enjoyable … I have my CAD program still on the computer, I still sit and work with them, out of my own interest … It's great to work. (Håkan, 70, recently retired mechanical engineer)

Anna-Greta: I like it very much. I have never thought a single day that it was miserable to go to work. (Laughs)

Interviewer: OK.

Anna-Greta: Privileged. Hairdressing is a … hairdressing is a really good occupation … all the clients become friends you meet regularly, right. Then you get without thinking about it, you get a sort of affirming need, you get so much affirmation, so you load up with energy from that all the time. That you get so much positive energy back … I hear from customers every day, yes but you can't stop and we are so glad that you work and you can't stop. (Laughs) … Yes, you get some sort of need for affirmation in this job, that you the whole time are marvelled for what you do. And it becomes that you like feel good because of that. Hmm, it is that which makes you feel good in this job. Satisfaction. (Anna-Greta, 69, hairdresser)

Several of the benefits of working which repeatedly appear: a sense of contributing, using expertise, and being valued by employers and colleagues, are self-esteem enhancing or, in more sociological terms, provide status. These status gains may be difficult or impossible to recreate in other life domains in the retirement years (e.g. the family role, volunteering) and highlight again the potential loss for those not able to participate in fulfilling work in later life.

An important sub-group of interviews contained people who, rather than enjoying their jobs per se, appreciated more the act of working. It was not the characteristics of the job as such that were in focus, but the contrast (imagined or experienced) with being at home. Ingegärd retired from her job as a nursing assistant as a result of poor working conditions, only to return to the same employer (unretire) two years later.

And so yes, one day I was furious and then just went and resigned … Eh, it was so tough and no organisation and it was … it was a battle then. (Ingegärd, 70, nursing assistant)

Less than enthusiastic about her work, it still provided for a better quality of life in the retirement years than being at home, an experience she found to her surprise to be miserable and boring. Taking up irregular shifts improved Ingegärd's quality of life by providing the stimulation, meaning and sociability she had lacked. This was the case despite the substantial psychosocial and physical demands of the job.

Receiving income from work was a necessary but not sufficient condition of working. Even for those living on low pensions, money was a subsidiary reason to work. Ingrid (66, retired manager) dismissed her earnings from her work as a water aerobics instructor by saying that they were mostly taken by the taxman. Hozan (69, retired native language teacher), who had a low pension as a result of immigrating from outside the EU in mid-life, had wanted to work after 67 years but had been unable to. When asked whether improving his finances had motivated his desire to stay in work, he stated: ‘Not 100 per cent, my interest had great importance as well. Let's say 50/50. It was interest that made me want to work.’ The psychological rewards of work were as important. Similarly, Shirley (68, retired laboratory worker and alternative therapist) noted that although her pension was low, and nothing to cheer for, she would not work merely to raise money. Such statements do not render earned income unimportant. Earnings have a symbolic quality, as a valuation of a person's labour. One interviewee on a low pension would have preferred to keep working, but elected to cease working after being offered a derisory salary by her previous employer:

I would have kept working as I had been, on an hourly basis. But they proposed that I would receive a lower salary and it was such a big difference that I thought no, then I'm not doing it … I would have got a lower salary, even lower than in 2013 … I said that this is ridiculous, to get such a proposal … it is the same work that I've done to date. (Nadja, 72, retired pharmacist)

To relate this theme back to the wider context, the landscape of the retirement years provides the setting for the rewards of work. The participants’ focus on the here-and-now against a background of looming death and serious illness explains why work needs to be intrinsically and immediately satisfying, at least compared to the competing option of a retirement lifestyle. Participating in work may also enable some temporary resistance against taking on an identity as an older person; in this way, work may provide comfort:

I would like to emphasise that it is really refreshing to actually get to work after age 67 … to socialise with younger colleagues and … I mean that it is so, you get to share your experience, you get a community back, you feel younger when you are working with younger people. (Ulf, 69, engineer)

Contained commitments

By being able to refuse work, post-retirement workers were able to contain their commitment to paid work. It appears that this notion of contained commitments was central to the choice to remain in paid work. Certain characteristics of the landscape of the retirement years made containing commitments possible. The interviewees had a known and secure income from their old-age pension(s), consequently, they could cease working at any point and switch to a more conventional retirement lifestyle, just as their peers already had. Against a background of a sense of contraction of the future, the interviewees refused to commit to long-term projects: they let employers know they are working for a limited time, taking things a year or so at a time. The view of their work prospects was similarly immediate: there was no talk of career building or hoping a work situation will improve one day. Participants shaped their work in various ways in order to contain their commitments and improve their working conditions. These included selecting a nicer work environment or employer of those known previously, selecting an employer or clients based nearer home and selecting which tasks or jobs to take. However, the main aspect that participants shaped was work time and scheduling.

A priority for the interviewees was to prevent work from spilling over into other valued activities and to reduce the suffering that work can generate. By containing work, participants could carry out other activities important to them, avoid being rushed and maintain a good quality of life. For some participants, there was a sense of finally being in control of one's own time, after many years of their time being directed by the demands of others. The freedom that contained commitments represented was strongly welcomed:

Hulda: But then I think, this freedom to work when I want. It is worth so much.

Interviewer: And you have that when you are working on an hourly basis?

Hulda: Yes, of course. I can say no, they can ring me and no, I don't want to work a night.

Interviewer: No, hmm. In some way, you steer over…

Hulda: I steer over my working time now. The disadvantage is that you have got older, one should have been able to do this at 40. To steer over one's own time, it's worth gold. (Hulda, 68, midwife)

While several aspects of paid work featured in negotiations with potential employers, controlling time spent working and the scheduling of work dominated. Participants frequently used the words ‘direct/steer’ (orig. ‘styr’), ‘decide’ (orig. ‘bestämma’), ‘choose’ and noted that they were not ‘locked’ (orig. ‘låst’) or ‘bound’, and that they were free from demands on their time (orig. ‘krav’). This freedom was entirely different to offers people recalled from their years in the core-age workforce, such as flexible working arrangements of various sorts, small reductions in working time or being able to work partly from home. There were at least three aspects of work time that the participants exerted control over: timing, intensity and rigidity of scheduling. It appeared to be a necessary condition for working that the participants were able to control their work time. Time spent working was a focus for negotiations with employers:

…he [my boss] came and asked, I didn't think … I hadn't thought about it when I resigned in order to retire. But then he came and asked me if I could consider … but I didn't want to … because I don't manage too much and because I didn't want to be bound the whole time, so I said this, and he said that this is completely fine … I said that I will work about two mornings a week so … so, not in the summer because I don't want to work then, but yes, sure … he said, that's completely fine. Just write up when you work. (Gunilla, 68, retired archivist)

Gertrud explained in order to even consider paid work, her commitment to the organisation would need to be highly limited:

Gertrud: Yes, it would be this that you have some sort of project. There I have a clear responsibility and I also have complete freedom to decide when I work. That's how my husband works today.

Interviewer: By freedom, what do you have in mind?

Gertrud: Yes, that it's a beautiful day and I could go skiing, then I go skiing. (Gertrud, 68, retired head of personnel)

Certain participants had been selected to interview because they had been gradually reducing their working time, a working style in the late career which was overwhelmingly viewed as positive. Motivations for reducing working time included managing tiredness, managing the physical demands of the job and any physical pain generated by work, spending more time with a partner and making the transition to retirement more gradual:

Ove: So then I took out the pension as one usually does and then worked extra so to speak.

Interviewer: So you retired so to speak, at 65?

Ove: Yes, yes … so I didn't feel for starting to work 100 per cent in order to make a living. Therefore I took out my pension then so I could just work on the side with what the body could manage quite simply.

Interviewer: Hmm, right. May I ask if it was as a result of something … this with energy…

Ove: Yes, I felt that I couldn't keep going for eight hours at a time, week in and week out. (Ove, 74, electrician)

Having freedom to control and reduce working time appeared to improve working conditions. Working fewer hours extends recovery time (and, perhaps more saliently, time spent feeling energetic), making strenuous physical aspects of jobs more bearable. Reduced hours also appeared to alter the psychosocial character of jobs. Participants could sidestep less-desirable organisational and psychosocial aspects of work, such as unwanted responsibilities, conflicts and meetings. They could focus on what they perceived as the core of the job. As a result of not taking on such peripheral responsibilities, some pushback from colleagues might occur, but since the labour of the person older than retirement age was needed little could be done about it:

Hulda: You know, I don't need to be so engaged, there is that.

Interviewer: When you are employed by the hour?

Hulda: Yes, when employed by the hour. I don't need to think about the schedule, I don't need to think about training, if I don't want to, I don't need like to have students, sometimes they say that to me, ok, but well … you are much freer. (Hulda, 68, midwife)

Arvid: Yes, but I am happy at work. It is very … many people running about, but they think I just coast on them, by working one day a week.

Interviewer: OK.

Arvid: No, but I just drive to order so I don't really feel the pressure there that … if you had a salary. Because it isn't that you can live on that, but it is to keep the business going really, yup. (Arvid, 69, vendor and lorry driver)

Continual reassessment of the decision to work

The interviewees were employed on an hourly basis (timlön) or ran their own businesses, working arrangements which provided a great deal of freedom concerning their work time and whether to accept work at all. They could stop working whenever they wanted to. We observed that, for these participants working in the retirement years, the sentence structure ‘I’ + ‘verb’ was prominent in their accounts: ‘I'll take’, ‘I will’, ‘I want’, ‘I decide’ and ‘I don't have to’.

The retirement landscape is such that work had become an optional activity after many years of compulsion. The participants continuously reassessed their decisions to work in various ways, by logging into a computer system and registering future periods of availability, agreeing to or declining new work, agreeing to or declining hopping in to help out, making or reducing commitments to clients. Individual decisions to work were repeatedly replayed:

Since I was retired I could put myself which days I wanted to work and what times … it's like this, a message comes here, I put in [my hours] first and then a message comes that I can work. (Ingegärd, 70, nursing assistant)

…it is that which makes me keep on working. (Anna-Greta, 69, hairdresser)

…there is [work at] this outlet on Saturday, when we're travelling to the Canaries. And then that's one week, then after that I don't have anything to do, so I can speak with [shop location] again, that I can come in some days that week. If I want. (Birgitta, 71, retired teacher and shop assistant)

Borrowing language from Zygmunt Bauman, paid work in these years is a momentary settlement inclined to instability, and which is kept stable by the force of these repeated commitments. The unstable character of the ‘paid work in the retirement years’ state is likely related to the fact that the dominant script for people in this age group is retirement. The participants lacked normative pathways and institutional mechanisms that might support them to stay in work. Consequently, they had no choice other than to engage in do-it-yourself work practices.

Paid work in the retirement years is subject to push–pull factors regulating retirement processes. Individual preferences to remain in work can be overwhelmed if conditions change, such as if poor health emerges or an employer refuses to renew a contract. Although we describe paid work in the retirement years as a state marked by constant interrogation about whether to keep or stop working, we do not wish to imply that individuals necessarily have much control over whether they work. External factors could overpower individual decision-making as well as play into it. For certain interviewees, such as foreign-born Nadja and Hozan who were living on particularly low pensions, participation in paid work in the retirement years was not possible or was curtailed against their wishes. Our vision of post-retirement paid work as a variety of ageing is entirely compatible with prior research drawing out inequalities in access to paid work and the lack of control over working patterns and income that older people may experience.

Discussion

We advance a new variety of ageing in retirement: self-directed participation in enjoyable and fulfilling paid work, which enables people to delay the onset of reliance solely on old-age pensions. While older workers aged 50+ or 55+ are generally treated as a single group, our interview data show that paid work in the retirement years is a distinctive second stage in the late career. Unlike in the early part of the late career, paid work in the retirement years takes place against a background of stable and secure pension income, a social norm of a retired lifestyle and a sense of contraction of the future. Jobs in these years are characterised by immediate intrinsic rewards and processes of containing and reaffirming commitments to paid work. The period when paid work in the retirement years takes place runs in Sweden from around age 65 through to the early seventies and potentially later, but may be more usefully conceptualised as a state of mind rather than a strict age range (Moen, Reference Moen2016: 37).

The landscape of the retirement years

The nature of paid work in the retirement years is shaped by a particular emotional, material and normative landscape. The emotional aspect concerns the proximity of the looming fourth age, expressed in the interviews as concerns about potentially imminent serious illness and death (cf. Lynch, Reference Lynch2012: 118). In line with recent theoretical accounts of the fourth age, these imaginings related more to fantasy than to lived experience (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010; Grenier, Reference Grenier2012; West and Glynos, Reference West and Glynos2016); healthy life expectancy in Sweden for 65-year-olds is more than 15 years (Eurostat, 2019). The fourth age is often discussed in the gerontological literature in terms of illness, decline and dependence. However, it is vital to note that the anticipatory anxieties expressed by the participants also included death and had as their central element a sense of contraction of the future (Laslett, Reference Laslett1989: 14; Grenier, Reference Grenier2012: 186). Laslett (Reference Laslett1989: 13) argued that uncertainty about how long is left before these calamitous events occur is of ‘considerable symbolic significance’ for older people. The lives of our participants might currently be satisfying, but were lived in a state of uncertainty by not knowing how long they had left. These fantasies formed the background to the interviewees’ paid work activities, helping to explain their focus on the intrinsic benefits of work and taking control over the course of their lives (cf. Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Flisbäck and Lund2017: 47).

Another aspect of the retirement years’ landscape is the possibility to claim old-age pension. All the participants were receiving pension income, which provided them with material security. Having attained the age of old-age pension availability, older workers are decommodified from the labour market and are able to benefit from the income provided by a pension regardless of their labour market status (Wachtler and Wagner, Reference Wachtler and Wagner1997: 85, 101; Lynch, Reference Lynch2012: 120). For this reason, it is little surprise that financial factors, particularly the requirement to have a job to afford essential goods, are weaker motivations for performing paid work above pensionable age compared to slightly younger age groups (Smeaton et al., Reference Smeaton, Vegeris and Sahin-Dikmen2009: 37; Hokema, Reference Hokema2016: 227–229). Upon being able to claim pensions, older workers may change their priorities (cf. Lynch, Reference Lynch2012: 110; Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Flisbäck and Lund2017: 172). Specifically, it appears that workers older than pensionable age seek to work flexibly and less intensively (in other words, containing their commitments) rather than maximising income and job security (Moen, Reference Moen2007; Lynch, Reference Lynch2012: 106; Hokema, Reference Hokema2016: 241; Wentz and Gyllensten, Reference Wentz and Gyllensten2016; Wainwright et al., Reference Wainwright, Crawford, Loretto, Phillipson, Robinson, Shepherd, Vickerstaff and Weyman2019). Fréter (Reference Fréter, Kohli, Fréter, Langehennig, Roth, Simoneit and Tregel1993) developed the concept of the pensioner job (orig. ‘Rentnerjob’), in which, compared to earlier in their lives, pensioners in paid work were less strongly engaged in their work, avoided exposure to stress and job demands, worked voluntarily and sought, rather than income, having a purpose and being around people. Fréter (Reference Fréter, Kohli, Fréter, Langehennig, Roth, Simoneit and Tregel1993) suggested that, in exchange for this flexibility, the oldest workers were prepared to sacrifice pay, job security and status. Future research could examine the specific types of job-crafting practice taking place in the retirement years in terms of which aspects of the work environment the oldest workers seek to influence and how they go about doing it (Wrzesniewski and Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001; Kooij et al., Reference Kooij, Tims, Kanfer, Bal, Kooij and Rousseau2015).

The nature of paid work in the retirement years

The prominence of intrinsic factors for the decision to remain in paid work in the retirement years is in line with prior research (Wachtler and Wagner, Reference Wachtler and Wagner1997; Deller and Maxin, Reference Deller and Maxin2008; Lynch, Reference Lynch2012; Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Farrow and Blank2012; Hokema, Reference Hokema2016; Wentz and Gyllensten, Reference Wentz and Gyllensten2016; Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Flisbäck and Lund2017; Bengs and Stattin, Reference Bengs and Stattin2018). We observed jobs that were enjoyable, stimulating and meaningful, at least compared to the alternative of a retirement lifestyle, but the jobs were generally prosaic. Perhaps because we sampled purposively from a wide range of education levels, only exceptionally could the jobs be described in terms of a ‘calling’, ‘new meaning’ or ‘powerful vision of purpose’ (Freedman, Reference Freedman2008; Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Flisbäck and Lund2017). As seen in prior research, the interest was often in continued activity that was reasonably intrinsically rewarding, at least compared to the alternative of being at home (Fréter, Reference Fréter, Kohli, Fréter, Langehennig, Roth, Simoneit and Tregel1993; Wachtler and Wagner, Reference Wachtler and Wagner1997; Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Parry and Taylor2004: 15–18; Hokema, Reference Hokema2016: 193).

We observed that participants sought to contain their commitment to paid work especially strongly in relation to working time. Other researchers have similarly observed the premium that workers in the retirement years placed on preserving their autonomy and agency (Lynch, Reference Lynch2012: 106; Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Flisbäck and Lund2017: 172). Deller and Maxin (Reference Deller and Maxin2008) noted how the freedom won by retiring must not be endangered and how flexible working times emerged as the principal determining factor for participation in paid work. Lynch (Reference Lynch2012) similarly observed the importance of extreme flexibility of scheduling to the workers at Vita Needle while, in Sweden, Wentz and Gyllensten (Reference Wentz and Gyllensten2016) described how workers in the retirement years had attained an ‘almost paradisiacal work–life balance’. The strong preference for part-time working expressed by workers older than traditional retirement ages is in line with wider literature studying the late career (Lain and Loretto, Reference Lain and Loretto2016) and corresponds to Moen's (2007) observation that encore workers desire ‘not-so-big’ jobs. Alongside reductions to working hours, workers above pensionable age demanded a step-change in control over their working time. Moen (Reference Moen2016: 68–70) has introduced the concept of the ‘work-time mismatch’, which encompasses rigidities regarding factors such as the amount of time spent at work, need for physical presence at work and degree of control over scheduling (Pitt-Catsouphes, Reference Pitt-Catsouphes2018). Workers over pensionable age may strongly appreciate their work but nonetheless seek to escape the disciplinary aspects of work and to gain freedom to use their time and energy for other valued activities (Meltzer, Reference Meltzer1981). We acknowledge that there is a risk of overstating the degree to which our interviewees exercised genuine choices over their work (Krekula and Vickerstaff, Reference Krekula, Vickerstaff, Ní Léime, Street, Vickerstaff, Krekula and Loretto2017). Older employees may exert influence over the work-time mismatch because this is the point that can give and may have experienced greater difficulties in tailoring other aspects of their work in the face of employer reservations and social pressure from other employees.

Our participants viewed their possibilities of remaining in paid work as susceptible to externally imposed and uncontrollable changes in boundary conditions, such as changes to health fortunes, characteristics of work or employer preferences, leading to a focus on the here-and-now. These observations are in line with the prior literature, which has observed participants limiting planning to the short term or resisting planning entirely in an ‘Undsoweiter’ perspective in which they will keep going as long as they can (Fréter, Reference Fréter, Kohli, Fréter, Langehennig, Roth, Simoneit and Tregel1993; Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Parry and Taylor2004: 33; Hokema, Reference Hokema2016: 197–199). They also correspond to predictions made by socio-emotional selectivity theory that, as a person's perceived time horizon becomes more constrained, the motivational priorities of the oldest workers will shift towards more immediate payoffs and a focus on regulating emotional states to maintain wellbeing (Carstensen, Reference Carstensen2006).

Some of our retired participants had not managed to participate in post-retirement paid work despite wishing to. Wilcock (Reference Wilcock1993: 23) argued that people ‘are occupational beings with a need to use time in a purposeful way’; in this light, occupational deprivation seems an apt concept to apply for involuntarily retired older people (Wilcock, Reference Wilcock1998). Alongside the intrinsic losses of occupational deprivation, not having paid work has economic costs. Gerlich (Reference Gerlich2019) has observed that post-retirement workers avoid the drop in satisfaction with own and household income that people who fully retire experience. Financial penalties for not finding post-retirement work will be particularly salient for those on low pensions: women and people who came to Sweden in mid-life from outside the EU or Nordic countries.

Future research directions

Viewing participation in paid work after the age of old-age pension eligibility as a phenomenon in its own right, rather than as a transitional state within the retirement process, has important implications for future research. In this stage of life, with its anticipatory anxieties of death and serious illness, normative expectations of a leisure lifestyle and the material security provided by pensions, preserving the freedom won by retirement and the optimising of the intrinsic benefits of work take on a new importance. Although a blunt negotiating tool, pensioners who are working voluntarily can employ the prospect of retiring from work as a realistic threat. Kohli and Rein (Reference Kohli, Rein, Kohli, Rein, Guillemard and van Gunsteren1991: 18) noted how such circumstances affect the power dynamics in the employer–employee relationship in such a way that employers will have to make offers of work more attractive if they wish to retain the oldest workers. Such processes might generate improvements in work quality and in employee control over work time (cf. Reference Sacco, Cahill, Westerlund and Platts2022), an area almost entirely unexplored in qualitative and quantitative research. Previous qualitative research into workers older than pension age has observed aspects of this intriguing phenomenon but, to our knowledge, no studies have had such negotiations as their central focus (Fréter, Reference Fréter, Kohli, Fréter, Langehennig, Roth, Simoneit and Tregel1993; Hokema, Reference Hokema2016: 241; Wentz and Gyllensten, Reference Wentz and Gyllensten2016; Bengtsson et al., Reference Bengtsson, Flisbäck and Lund2017: 43–44, 46).

This article has drawn out some of the characteristics of the period of ‘post-retirement work’ in Sweden, a country with near-complete welfare coverage of older people as well as plentiful high-quality jobs. The pattern of working in later life described in this paper can be viewed as an achievement of Swedish social and economic policies. However, welfare retrenchment reducing the replacement rates of pensions may cause this situation to change. It is important to note that, in order to carry out the consent procedure in the Swedish language, we were not able to interview the most vulnerable older people, those who arrived in Sweden in late mid-life, who are compelled on financial grounds to participate in the labour market or rely on family for support. Alongside research into harder-to-reach groups, qualitative research in countries with less-generous welfare and pensions arrangements is needed. Such research would indicate whether the intrinsic benefits and contained commitments of paid work in the retirement years also occur elsewhere, or if this type of work is confined to the most protective welfare states or the most advantaged groups.

Conclusion

We advance a new vision of ageing in retirement: self-directed participation in enjoyable and fulfilling paid work during years generally viewed as set aside for retirement. We argue for the interest of conceptualising the late career in two phases, in which working after typical ages of eligibility for old-age pensions is distinctive enough to form a new career phase. It may be in this second phase of the late career that an emancipatory vision of employment in old age is emerging (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson, Minkler and Estes1999).

There are many positives of post-retirement paid work: growing the economy, funding the welfare state, counteracting skills shortages, and supporting the wellbeing and finances of older people themselves. However, in Sweden, like other advanced economies, policy makers tend to ignore the fact that many people work in retirement (Pensionsåldersutredningen, 2013: 127–129). Certain policies actively counteract participation in post-retirement work, including mandatory legal retirement ages and ineffective implementation of age discrimination legislation. The need for older people to find ad hoc arrangements to remain in work is due to the lack of formal arrangements that would support their labour market participation (Moen, Reference Moen2016: 54, 68; Wainwright et al., Reference Wainwright, Crawford, Loretto, Phillipson, Robinson, Shepherd, Vickerstaff and Weyman2019). The benefits to employers, employees and society as a whole of post-retirement working could be maximised were governments, employers and social partners to reflect on ways to formalise post-retirement employment options with an eye to sustainability and equitability.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yvonne Janzén (Literatim Skrivbyrå) for skilfully transcribing the interviews. The interviewees receive our appreciation for sharing valuable accounts of their lives and activities.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: LGP, AI, HW, DR; data collection: LGP, DR; data analysis and interpretation: LGP, AI, DR; drafting of the article: LGP, AI; critical revision of manuscript and approval of version to be published: LGP, AI, HW, DR.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (2017-00099). The funder played no role in the design, execution, analysis and interpretation of data, or writing of the study.

Conflict of interest

LGP has a collaboration with the Swedish National Pensioners’ Organisation and is on the board of the Swedish association Pensionsrättvisa (Pensions Justice). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical standards

The regional ethics board in Stockholm approved the study (dn 2018/1767-31/5). Participants gave oral consent just before the interview and written consent afterwards. All participants are referred to by pseudonyms.