Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the use of music, and the arts more generally, with people living with dementia (Beard, Reference Beard2012; All Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing, 2017; International Longevity Centre, 2018; van der Steen et al., Reference van der Steen, van Soest-Poortvliet, van der Wouden, Bruinsma, Scholten and Vink2018). A wide range of music programmes have been reported in the literature, including music therapy delivered by qualified music therapists, choirs and singing groups, personalised playlists, as well as composition and musical performances (Camic et al., Reference Camic, Williams and Meeten2013; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, Greasley-Adams and Goodson2015; Unadkat et al., Reference Unadkat, Camic and Vella-Burrows2017; McDermott et al., Reference McDermott, Ridder, Baker, Wosch, Ray and Stige2018). Such programmes have been shown to improve symptoms of depression, strengthen relationships between couples and provide opportunities for people living with dementia to learn new skills (Camic et al., Reference Camic, Williams and Meeten2013; McDermott et al., Reference McDermott, Orrell and Ridder2014; Unadkat et al., Reference Unadkat, Camic and Vella-Burrows2017; van der Steen et al., Reference van der Steen, van Soest-Poortvliet, van der Wouden, Bruinsma, Scholten and Vink2018). Most commonly, the impacts of music for people living with dementia are understood in the context of programmes delivered within care home settings (e.g. Pavlicevic et al., Reference Pavlicevic, Tsiris, Wood, Powell, Graham, Sanderson, Millman and Gibson2015; Garabedian and Kelly, Reference Garabedian and Kelly2020), with there being fewer examples of work with people living with dementia living at home within the community (Elliott and Gardner, Reference Elliott and Gardner2018; Dowlen, Reference Dowlen2019; Melhuish et al., Reference Melhuish, Grady and Holland2019).

Although there is growing evidence of the benefits of music for people living with dementia, the dominant narrative is biomedical in nature. Here, music is considered as an ‘intervention’ of which success, or failure, is measured against the reduction of a range of ‘behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia’ (BPSDs), such as a lessening of the signs of agitation following a time-limited music-based intervention programme (de Medeiros and Basting, Reference de Medeiros and Basting2014). The main outcomes observed in the literature – typically relating to BPSDs – are predetermined by researchers and/or clinicians which leaves the subjective musical experiences during the period of engagement significantly undervalued and under-reported (DeNora and Andsell, Reference DeNora and Ansdell2014). Research to date which has used pre/post-intervention approaches to understand the benefits of music for people living with dementia has been mixed, with many studies showing few changes in outcomes between music programmes and ‘normal activity’ (Ueda et al., Reference Ueda, Suzukamo, Sato and Izumi2013). However, qualitative literature paints a slightly broader picture with studies reporting on how music can create meaningful connections between the person living with dementia and others, and strengthen a person's sense of self-identity while being immersed ‘in the moment’ (McDermott et al., Reference McDermott, Crellin, Ridder and Orrell2013; Dowlen et al., Reference Dowlen, Keady, Milligan, Swarbrick, Ponsillo, Geddes and Riley2018).

The terms ‘in the moment’ and ‘the here and now’ are becoming increasingly common in the music and dementia literature (e.g. Killick, Reference Killick, Clarke and Wolverson2016; All Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing, 2017; Zeilig et al., Reference Zeilig, West and van der Byl Williams2018). There is evidently a wealth of information which can be gathered from examining musical experiences from the ‘in the moment’ positionality rather than relying purely on pre/post-intervention approaches. For example, both family carers and health-care professionals have reported the value of ‘in the moment’ musical experiences, noting that the experiences held ‘in the moment’ are not devalued if the perceived benefits do not last beyond the session time (Sixsmith and Gibson, Reference Sixsmith and Gibson2007; McDermott et al., Reference McDermott, Orrell and Ridder2014; Tuckett et al., Reference Tuckett, Hodgkinson, Rouillon, Balil-Lozoya and Parker2015; Osman et al., Reference Osman, Tischler and Schneider2016). A focus on ‘in the moment’ experience also provides opportunities to explore the musical abilities and creativity of people living with dementia (Killick, Reference Killick, Clarke and Wolverson2016; Bellass et al., Reference Bellass, Balmer, May, Keady, Buse, Capstick, Burke, Bartlett and Hodgson2019; Zeilig et al., Reference Zeilig, West and van der Byl Williams2018), rather than focusing purely on music as a means to reduce the occurrence and severity of BPSDs, however worthy that aim (Kontos, Reference Kontos, Hyder, Lindemann and Brockmeier2014).

Although the term ‘in the moment’ is becoming more common within the music and dementia studies literature, no published research has been identified by the authors that has had the core objective of understanding such experiences. To start to build such a foundation, this study used an embodied and sensory lens (Kontos, Reference Kontos2004, Reference Kontos2005; Pink, Reference Pink2007, Reference Pink2015) to explore the ‘in the moment’ musical experiences of people living with dementia in the context of an improvisatory music-making programme: Manchester Camerata's Music in Mind. The study context and design allowed for an opportunity to explore this phenomenon from within the temporal boundaries of ‘the moment’ as it is lived and experienced by the person with dementia (Eriksen et al., Reference Eriksen, Bartlett, Grov, Ibsen, Telenius and Rokstad2020; Keady et al., Reference Keady, Campbell, Clark, Dowlen, Elvish, Jones, Kindell, Swarbrick and Williamsin press).

Methods

This study adopted a multiple-case study design (Stake, Reference Stake2013) in order to gain an in-depth understanding of the ‘in the moment’ musical experiences of people living with dementia. This research was situated within one Music in Mind programme which took place in a community centre in Manchester between April and August 2017. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Social Care Research Ethics Committee.

Research context: Music in Mind

Manchester Camerata's Music in Mind is a music therapy-based programme for people living with dementia and their care partners. Music in Mind is co-facilitated by a music therapist and a Manchester Camerata orchestral musician. The principles of Music in Mind are centred on choice and agency for the person living with dementia, enabling a democratisation of the musical space through supported improvisation using percussion instruments, the human voice and body percussion.

Each Music in Mind programme is delivered over a period of 10–15 weeks and each session follows the same structure. The room, or space within a room, which is intended for the programme, is set up so that a circle of chairs is placed around a central table which contains an array of percussion instruments. Music in Mind practitioners position themselves within the circle of chairs rather than in a position that would suggest it is a musical performance which separates ‘audience’ and ‘performer’. This is a non-verbal indication of a collaborative music-making approach, with every contribution in the circle viewed as valid and each person viewed as a musician rather than separated by role or diagnosis.

The practitioners typically start the sessions with a ‘Welcome Song’. This song is consistent across the duration of the programme to allow for a non-verbal signal that the music-making is beginning and to acknowledge each group member's presence. The ‘Welcome Song’ is followed by the creative music-making part of the session, which provides an extended time usually lasting between 30 and 60 minutes. Within this time people living with dementia explore the different percussion instruments on offer to them, creating new music through supported improvisation, musical games, as well as singing and improvising around familiar music. Sessions are ended by the practitioners through a ‘Goodbye Song’, which is again consistent across the duration of the programme.

Study design

Within the multiple-case study design each person living with dementia acted as an individual case study and a cross-case sensory analysis was used to build thematic observations underpinning ‘in the moment’ experiences which were seen across cases. Within this overarching design, two research methods were used: video-based observation and video-elicitation interviews.

Participants

The first author worked closely with Manchester Camerata in order to recruit participants who were both interested in taking part in the Music in Mind programme and the research study. To be included in the research participants needed to: (a) have a confirmed clinical diagnosis of dementia; (b) have capacity to understand and consent to participate in the study (including those who can consent in the moment), or they have a personal consultee who could be identified and approached if individuals with dementia were not able to consent; and (c) have the ability to converse in English. We adopted a process consent method (Dewing, Reference Dewing2007) with a formal capacity assessment conducted in order to establish the basis for consent for each person living with dementia, which was monitored across the duration of the research study.

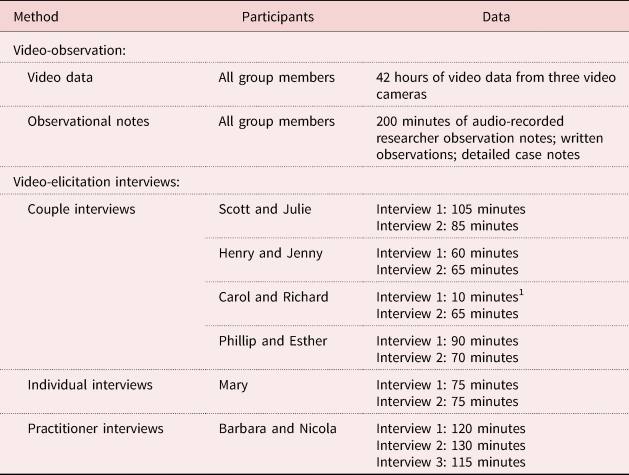

Six people living with dementia were recruited into the study as well as four family carers (see Table 1). For the purposes of protecting the identities of those involved, all study participants have been given pseudonyms in line with the ethical permission and study protocol. The two practitioners who were delivering the project were also recruited as participants (Barbara, a music therapist and Nicola, a Manchester Camerata musician). At the time of recruitment, the mean age of group members who were living with dementia was 62, with all but one (Scott) living with a diagnosis of a young onset dementia. Although we did not aim specifically to recruit a population of those living with young onset dementia, it is likely that this population was most prevalent within the group due to the Music in Mind programme being community-based. Out of the 15 Music in Mind sessions, Scott attended the most sessions (all 15) and Phillip/Carol the fewest (11 of 15).

Table 1. Participant characteristics

Video-based observation

The first author situated herself as a participant-observer within the context the Music in Mind programme and recorded each of the sessions using three video cameras, with two placed on tripods and the third operated by hand from her seat within the circle. This set-up enabled both the capturing of the wider group context as well as close-ups of individual music-making events. In order to build the relationship between herself and the participants, and to ensure each group member had provided consent/personal consultee agreement, the cameras were not turned on until week 5 of the programme. This resulted in video-observation being conducted between weeks 5 and 15 of the programme.

When the cameras were introduced in week 5 of the programme, the first author showed the cameras to each person living with dementia and their family carer as per the protocol within the process consent method. The first author made sure to introduce the cameras each subsequent week to remind participants of their presence but aimed to use the cameras in a way that was as unobtrusive as possible (e.g. using the zoom function to capture close-ups).

On reviewing the footage from week 5 in the programme there were a number of examples of participants looking directly into the camera lens, perhaps being more aware of how everything that they contributed within the space had been captured more permanently compared to more traditional field notes. However, these occurrences did not last after the first week, as if the novelty of the cameras being in the setting had worn off.

Video-elicitation interviews

Video-elicitation interviews use video of a given context of interaction to draw out deeper discussion about an experience than would be granted by a traditional research interview (Henry and Fetters, Reference Henry and Fetters2012). The first author identified video clips each of around 5–10 minutes in length from the video recording of the Music in Mind sessions to show to participants as part of video-elicitation interviews. These clips were chosen on an individual basis for each person living with dementia, exploring areas where a particular response to music had been observed within sessions (e.g. a ‘moment’ of sustained musical improvisation; a ‘moment’ that created joy or laughter for that individual; a ‘moment’ that was reported as important by the person living with dementia or their care partner within the sessions). These clips would include the person living with dementia and their family carer as well as other members of the group due to the nature of the camera set-up. It was, however, important that the opportunity to explore the relationships with others in the sessions due to Music in Mind being a group activity, with many participants recognising their fellow music-makers within the interview setting and commenting on exchanges held with them ‘in the moment’.

These interviews, lasting between 60 and 120 minutes, took place within participants’ homes and gave an opportunity to ‘re-live’ the sessions outside the context of the physical music-making space. Four couples participated in joint interviews and Mary (living with dementia) took part in an individual interview as her husband was not part of the Music in Mind group. Sam (living with dementia) contributed to the Music in Mind sessions but was not interviewed owing to the difficulties in finding a suitable time and place in which to conduct the interview.

Participants watched the video clips with the researcher and discussed their reactions to the video. This was also an opportunity to review reactions to the video for participants who had challenges in relaying their experiences using verbal language. Whilst the video-elicitation interviews themselves were not video recorded, the first author made notes while the person living with dementia watched the video footage of the Music in Mind sessions, paying particular attention to embodied and sensory experiences. The first author also kept a reflective observational log where she reflected further upon the research interviews as soon as possible after their completion. These observations were integrated into detailed transcripts alongside the verbatim words spoken by people living with dementia and their family carers, enabling the embodied practices exhibited in the interviews to be privileged through the researcher's knowledge of the ‘in the moment’ interaction.

Practitioners were interviewed together in a room at The University of Manchester, with the format of the interviews being very similar to those conducted in the context of participants’ homes.

Data analysis

In total, 42 hours of video data were collected within the context of the Music in Mind sessions. The combined data that were gathered as part of the study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview of research data

Note: 1. The audio-recording device malfunctioned, resulting in only a short piece of audio being captured.

While there are a number of approaches to data analysis within case study research, the process is predominantly guided by the research discipline, research questions and theoretical/epistemological positioning of the researcher (Simons, Reference Simons2009). Our approach to analysis was underpinned by definition of ‘being in the moment’ of Keady et al. (Reference Keady, Campbell, Clark, Dowlen, Elvish, Jones, Kindell, Swarbrick and Williamsin press) as ‘a relational, embodied and multi-sensory human experience’. As such, we used an embodied and sensory approach to analysis guided by Pink's (Reference Pink2015) description of sensory analysis in order to privilege the individual ‘in the moment’ embodied musical experiences of people living with dementia engaged with music-making.

The use of the video data within the sensory analysis was threefold and enabled: (a) the lead author to re-encounter the music-making space outside the session time to select video clips and analyse ‘in the moment’ experiences at the micro-level; (b) people living with dementia and their family carers to re-encounter the sessions and reflect upon their experiences of ‘the moment’ during interviews; and (c) the wider authorship to encounter the multi-sensory music-making space for themselves and to engage in reflective, and critical, discussion to ensure the rigour and trustworthiness of the analysis. This, combined with the transcripts from participant interviews, produced a multi-layered set of data for analysis which enabled the exploration of individual and collective group experiences.

While the section above outlined the overarching approach to analysis of the research data, the next section will outline the steps taken to develop rigorously findings from the wealth of data collected within this study.

Phase 1: Building individual ‘in the moment’ case profiles

The purpose of the first phase of analysis was to build individual ‘in the moment’ case profiles for each person living with dementia. This was achieved by viewing and re-viewing the video data, as well as by reading and re-reading interview transcripts for each person living with dementia. Whilst the video data captured both individual and group experience given the context of the Music in Mind sessions, the focus was placed on one person at a time, making detailed moment-by-moment analytic notes relating to verbal and non-verbal practices and interactions during the sessions. These moment-by-moment analyses were then used to build a thick description of experience written up into individual case profiles for each person living with dementia.

Phase 2: Translating understanding across case studies

Once all individual case profiles had been written, the lead researcher and first author reviewed each of the case studies and identified elements of experience that were translatable across the profiles as part of a cross-case analysis (Stake, Reference Stake2013). This enabled the opportunity to examine elements of experience which were common for people living with dementia within the group, but also provided opportunity to identify any negative cases where a particular experience was not universal. From this approach, thematic observations were subsequently developed that encapsulated translatable elements of ‘in the moment’ experience. Descriptions and examples of these experiences were written into a group profile, outlining each of the thematic observations with illustrative examples taken from the video data and participant interviews.

Phase 3: Building a multiple-case study narrative

In order to develop rigour and trustworthiness with the thematic observations, segments of the video and the thematic observations were reviewed and tested within monthly meetings with the wider authorship of the paper in order to discuss the interpretation of the data by the first author. This iterative process of theme development occurred over several months, with the lead author re-examining the thematic observations considering the wider group analysis. This led to the development of four key thematic observations which were developed into a wider multiple-case narrative. These four observations are presented within the following section.

Findings

The sensory analysis led to the development of four thematic observations which highlighted elements of ‘in the moment’ experience observed across all people living with dementia: Sharing a life story through music, Musical agency ‘in the moment’, Feeling connected ‘in the moment’ and Musical ripples into everyday life. These observations will be illustrated through examples drawn from the case studies of people living with dementia. All images have been manipulated to protect the identities of those involved in the study. Permission was sought from each group member to use these images of themselves in line with the study protocol.

Observation 1: Sharing a life story through music

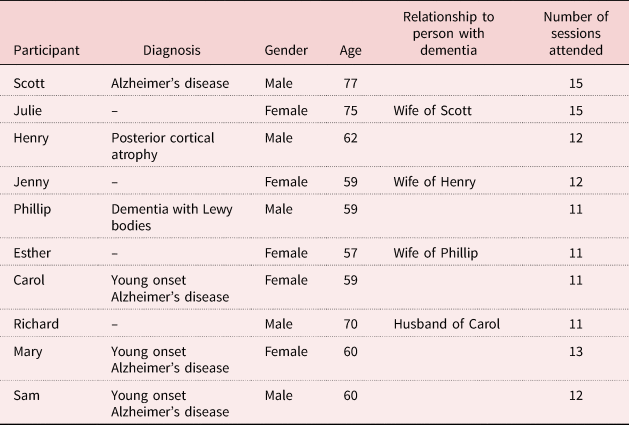

The examples underpinning this observation highlighted the way in which people living with dementia embodied their life stories through their interactions with music ‘in the moment’. People living with dementia had individual preferences for specific musical styles, as well as strong embodied and emotional reactions to particular songs, including looking towards the music therapist's keyboard on the introduction of familiar melodies or musical styles, seeking eye contact and smiling at other members of the group, tapping their feet, extending a hand to other group members or even getting out of their seats to dance. For example, Figure 1 showcases Scott's reaction to a familiar melody. On hearing the melody, he put his arm around the lead author and smiled, drawing her in close to him to share in a moment of laughter and togetherness. Showcasing these strong individual preferences led the Music in Mind practitioners and other group members to ask questions relating to people's life stories, enabling the group to be able to learn more about each other without the focus of the interactions being placed on reminiscence alone.

Figure 1. Scott (centre) puts his arm around the lead author (right) and they smile and laugh with each other.

For example, during one session, Mary (living with dementia) revealed that she had worked for UNICEF as a nurse where her role was to provide health and nutritional education to families living in Nigeria. Knowing this part of Mary's life story enabled an exploration of her embodied musical experiences through the lens of her past life experiences. This was particularly evident when Mary chose to teach the group new songs that had significance to her. Her ability to lead the group and support the group members in learning a new repertoire was skilful and creative. On asking Mary about her teaching skills during an interview, she stated:

I used to go out to teach community women. I teach them a lot, I work with them, UNICEF, British Council, mobilising them to do something useful for themselves. So, I've got that skill of accepting everybody and coming down to everybody's level … This group are teachable ’cos everybody's looking forward to being happy at the end of the day so you have to participate to teach people, you don't give them instruction, participate.

Mary, therefore, was able to share her love of music with her teaching skills and was often viewed as a facilitator for others in the group, encouraging others to choose instruments by taking a selection to them or through teaching the group songs that were significant to her.

Another clear example of this embodied intersection between music and life story was illustrated by Henry (living with dementia) who, during one session, chose an ocean drum to play. On picking up the drum, Henry tilted it on its side and began to play with his thumb and little finger (see Figure 2). This is not the typical way in which an ocean drum should be played, with it usually making sound through the player rotating the drum so that the metal beads inside make a sound similar to water rolling across the shore, which had been demonstrated to the group by the practitioners when the instrument was introduced to the group. However, Henry's embodied practice was more representative of the way in which a bodhrán (an Irish frame drum) would be played, with the drum played on the knee and the beater poised between thumb and middle finger. This led the music therapist to play an improvised melody focused around the key elements of a jig (e.g. fast, lively music in 6/8 time) which Henry responded to by playing the drum in a more animated fashion, smiling and laughing with his wife Jenny.

Figure 2. Henry plays the ocean drum in the style of a bodhrán.

After this interaction, Jenny shared Henry's Irish family heritage to the group, explaining his love and appreciation of music and dance which had been encouraged in his life by his family since he was a child. When interviewing Henry and his wife Jenny, the context for this embodied action became more evident, as he discussed his Irish heritage and love of Irish music:

Henry: I've got a lot of Irish.

Jenny: Well all your family you're Irish bred, weren't you? English born but Irish bred.

Henry: Yeah (laughs).

Researcher: I think you said in one of the sessions about going to the clubs and the Irish music?

Henry: Oh yeah that's right.

Jenny: The [name of pub] in [neighbourhood of Manchester].

Henry: That's what we would do. The [name of pub] yeah.

Jenny: On a Saturday or Sunday all the music, oh it was great, great, really great, yeah. The old lady playing the bodhrán, do you remember?

Henry: That's right yeah.

Jenny: She was fabulous, a little old lady with a bun.

Henry: Yeah (laughing).

Jenny: Oh, it was fabulous there then.

Henry's dementia had led him to have word-finding difficulty and he was often seen to get frustrated in the sessions when he was unable to express himself verbally, and so music-making afforded him the opportunity to showcase elements of his personal history with the group without having to express this verbally.

Another clear example was seen during one Music in Mind session when Esther (family carer) asked the group if they could sing Abide with Me as it was Phillip's (living with dementia) favourite song. The group sang together accompanied by Barbara (the music therapist) and Phillip began to cry. His tears were not signalling any distress, but rather an emotional reaction to being sung a personally significant song by a group that he had developed a sense of connection with over the course of the programme. Phillip had difficulties in being able to express himself verbally and so the opportunity to sing with a group supporting him provided a moment of felt emotion for everyone in the group. We learned that Abide with Me had been the song that Phillip had chosen to signify his confirmation within his church when he was a teenager. This song held a strong connection to Phillip's sense of identity and as a result, group members requested to sing this song across the duration of the project, embellishing with harmonies and accompanying with soft percussion to enable Phillip to experience that moment of happiness again and again.

Overall, this thematic observation highlights the intersections between the life stories of people living with dementia, their musical history and their ‘in the moment’ experience. It acknowledges the importance of using life story as a lens for contextualising ‘in the moment’ experience as well as embodied action within the context of music-making.

Observation 2: Musical agency ‘in the moment’

This thematic observation highlights the way in which music afforded people living with dementia more agency ‘in the moment’, enabling them to make active choices and participate fully with the support of the music therapist and musician. For example, in the earlier weeks of the programme, people living with dementia needed to be prompted to choose instruments from the central table. However, in later weeks group members were quick to reach for the instruments, perhaps having their musical agency validated through their improvisations in previous weeks. This, combined with the failure-free musical environment created through the improvised music-making approach, allowed participants to be more confident in their instrument selections.

From very early on in the programme it was evident that there were instruments to which each group member was drawn. Group members tended to return to the same instruments time and time again, unless encouraged to try something different by the practitioners. This perhaps showed that everyone had a fondness for particular musical timbres (tonal qualities). Group members were also aware of the instrument preferences of others, without these having to be vocalised by the person living with dementia, with many group members mentioning the likings of others within research interviews, as the excerpt below from a family carer illustrates:

People certainly had their favourites in terms of instruments [agreement from Carol]. Henry with the glockenspiel [Carol laughs] and Mary liked the pluck guitar thing [referring to a lyre]. (Richard)

Group members were observed to develop interests in new instruments over the duration of the programme. Henry (living with dementia), for example, started the programme with a preference for maracas and bells but in the last five weeks of the programme the glockenspiel became his preferred instrument. He really thrived with this instrument and was able to improvise for up to ten minutes at a time. Henry was applauded for his musical contributions and this positive feedback led to his sustained musical involvement.

Phillip, on the other hand, preferred to use his voice to contribute to the music-making. Phillip would rarely play an instrument for himself but would contribute through humming. This was not always evident to other group members, and so the skill of the practitioners lay in being able to find moments of quietness in which Phillip's voice could be heard and shared with the group. The following quote from the music therapist illustrates a moment where Phillip's voice was able to be heard by the group members:

What's amazing is how he sticks with it. He just carries on singing for the best part of two minutes isn't it? I think that tells us that it's alright … it's sitting alright with him. The music kind of meets him I think, and the fact that most of the group are listening to it is just wonderful and that always tells me that the connection is audible. The connection between my playing and him, in this case, mostly is audible to everybody and it's musically so exciting that they think ‘oh!’ Or so complete that they stop playing and they find that their attention is drawn to that.

As well as each group member having a preferred instrument, there were different types of musical accompaniments or melodies which resonated with different individuals of the group. These preferences were outwardly displayed both verbally and non-verbally (e.g. cheering, sitting forwards in their seat, dancing). Individuals showed both a preference for certain musical styles (often familiar songs) but also different musical elements (harmony, rhythm and melody). For example, Mary (living with dementia) enjoyed melodies in a major key with simple chord progressions, perhaps reflective of many of the gospel songs that were an integral part of her worship practices. Henry (living with dementia), on the other hand, really appreciated Latin American rhythms and would jump out of his seat to dance in the middle of the circle the minute the practitioners introduced such rhythms. These musical preferences were encapsulated by the music therapist, who said:

They say that we're all rhythmic. I mean, that we've got predominantly one or the other. Rhythmic beings, harmonic beings … I mean each of these musical parameters define any individual, I think.

People living with dementia also showcased agency through their musicianship (which encompasses musical skill and performance abilities) across the duration of the Music in Mind programme. This musicianship was often acknowledged through the group by means of a round of applause and/or cheering. This positive feedback may have instilled a sense of self-belief in the person living with dementia, reinforcing their sense of contributing as equals within the music-making space and reaffirming their agency within the context. This atmosphere of creative equality was illustrated through a number of quotes taken from the research interviews:

I think [music] just puts everybody on a level. You don't realise some of them are disabled, you know, because they don't need to, they just do it. I mean some of them need a bit of help to get going but once they get going, I think that it masks, not masks the disability, but the disability isn't important. We're all equal and it equalises them all, I think. (Julie, family carer)

And you just hear people's voices when their voices, like Scott, his voice isn't what it was, he can't express himself vocally like that, but we all know that he's speaking … It's just so equal isn't it? That's what's so nice about it. (Nicola, musician)

I think it's also with knowledge, everyone in the group knows that Phillip knows [the song Da Na Se] and loves it as well. So that's when we're talking about all being equal that's the point in the session, when you know that there's something that every single person will connect with. (Nicola, musician)

The musical skills and creativity of people living with dementia was acknowledged by all group members, with the practitioners and family carers expressing surprise at the skilled playing by people living with dementia, as the quotes below illustrate:

Gosh, he's playing really well isn't he! … I hadn't realised you'd played that much. You obviously enjoyed playing that Scott. That was amazing. With him sitting next to me I didn't realise he'd played it quite so well… (Julie, family carer)

Carol comes in off-beat with long up-beats. It's quite intricate, it's quite varied and imaginative, and it's not copying but responding, which shows a sense of independence and musicality and courage and imagination. (Barbara, music therapist)

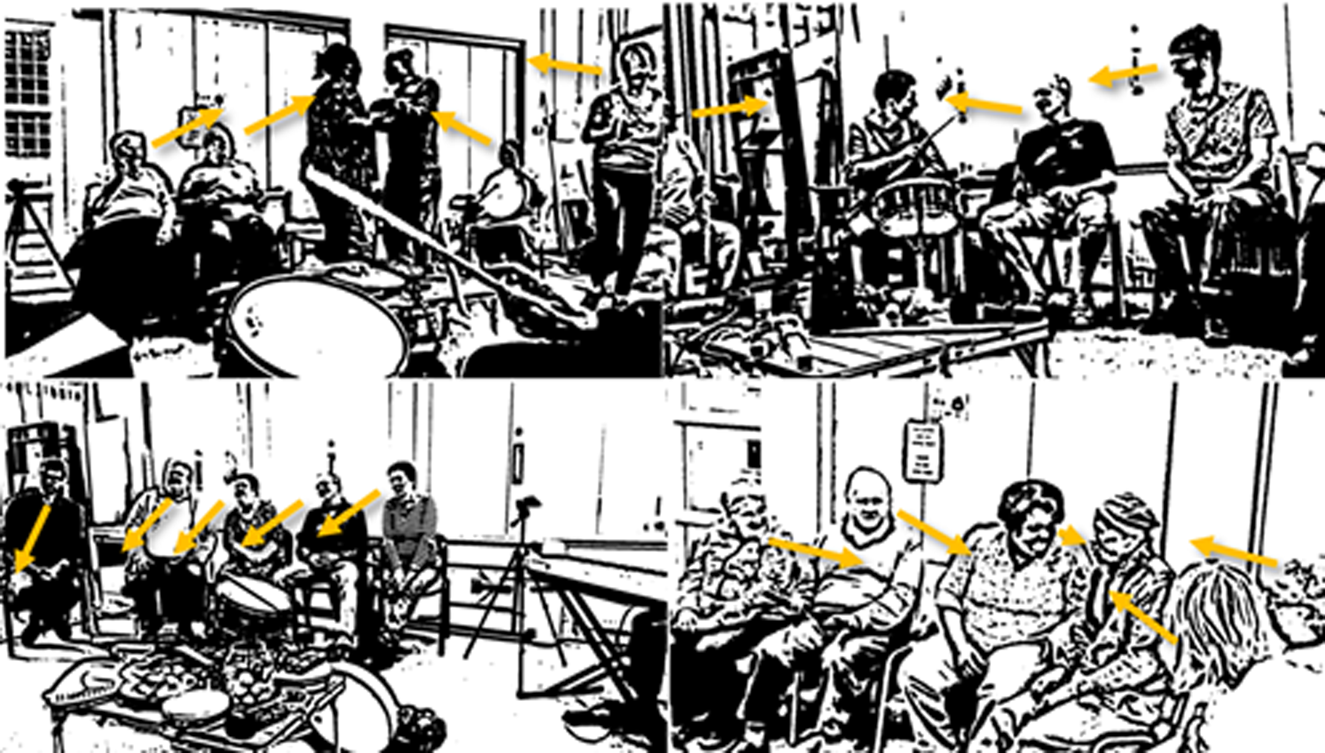

Not only did people living with dementia showcase musical skills such as keeping to time and improvising melodies, they brought their performances to life by conveying emotion using musical dynamics (variation in loudness) and used their bodies to tell musical stories through gesture and facial expression. These musical performances were often the spotlight of the group's attention when they occurred, and resulted in laughter and cheering from the group who recognised the humour in the performances. Figure 3 shows a drum improvisation between Sam (living with dementia) and Nicola (musician), where Sam instigated a comical sword fight using his drumsticks which was met by laughter from the group. During this interaction, Barbara (music therapist) adopted a minor key and played an accompaniment that evoked an atmosphere of menace and playfulness. This added to the musical storytelling, which was initiated by Sam, adding to the slapstick nature of the interaction.

Figure 3. Sam initiates a play fight with Nicola.

These opportunities for extended musical improvisation and musical performances enabled people living with dementia to feel wholly immersed in the music-making experience. During these moments, people living with dementia acted with complete absorption when creating new improvised melodies. These moments of immersion were often noticed by the wider group, creating musical spotlights in which the person living with dementia had the opportunity to be the focus of the group's attention (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. People living with dementia become the focus of the group's attention.

The following quote from Mary (living with dementia) reflects on one such moment of extended improvisation:

I was able to play all things. Makes meaning to me. I don't know whether it's making any meaning to anybody else but it's giving me concentration. You know I found it difficult to concentrate, first I wanted I would stop it, I'd start another thing, and I'd stop it. But when I'm playing one thing, I tend to get the concentration. I want to hear what I'm playing whether it's making any good sound that makes meaning or I'm just making a noise. But I can see it bringing down my concentration and I would like to focus on it for the period I'm holding that particular [instrument]. I want to make good use of it … It's like putting your best. Play what you can play, that is why you see me. I play many, many [instruments] but I think it makes sense to me ’cos I can hear the sound and I'm enjoying it. It might not be pleasant to another person ’cos I'm not listening to that one. I'm listening to what I am. But when we do like this, you know that somebody's listening to you.

This excerpt illustrates the immersive state Mary entered when improvising. It highlights that her improvisations were driven by her own aesthetic goals, meaning she could create music that was significant and meaningful to herself rather than aiming for it to be pleasing to other people. Mary's improvisations often centred on hymns and gospel music she sang at church and so these extended moments of immersion may have also given her the opportunity to meet some of her own spiritual needs.

Overall, this thematic observation shows the ways in which music afforded a heightened sense of agency and a platform for self-expression for people living with dementia, enabling them to make decisions relating to the instruments they chose and for their musical contributions to be heard and appreciated by other members of the group.

Observation 3: Feeling connected ‘in the moment’

Music-making enabled each person living with dementia to feel connected to other members of the group, as will be exemplified below. This highlighted the relational aspects of ‘in the moment’ experience. Sharing in a unifying experience enabled people living with dementia to make meaningful connections with other group members, whether it was their spouse, other group members or the practitioners. This sense of connection allowed the person living with dementia to feel more confident in their musical contributions, feeling more relaxed in the company of the other group members as the sessions went on, through instances of enhanced physical contact and eye contact, for example.

One clear example of musical connectedness occurred in week 12 of the programme between Scott and Phillip (both living with dementia). The group was singing Phillip's favourite melody (Abide with Me) and Scott reached his hand out to connect physically with Phillip (see Figure 5). The two men, who both had challenges relating to verbal communication, connected physically in a way that did not need words. This simple gesture of reaching out during a song that had special meaning for Phillip was a visible gesture of friendship and support from Scott. This interaction happened the week that Phillip returned from a two-week respite, perhaps signifying that Scott noticed his absence from the group and was welcoming him back into the music-making space.

Figure 5. Scott extends his hand towards Phillip.

There were also non-conscious moments of connection that were observed between group members. The group members’ bodies were seen to synchronise both with the musical beat and the bodies of others. This was most obviously observed when individuals swayed in time with each other, their bodies almost taking on the role of a metronome. This subconscious bodily entrainment could have enabled the people living with dementia to feel more connected to other group members because of this synchronous experience. This sense of synchrony was also enhanced through the use of mimicry both of gesture and facial expressions, as well as musical or rhythmic phrases. This created a sense of group cohesion which was facilitated by the shared activity of improvisatory music-making.

People living with dementia were also able to use music as a communicative device within the Music in Mind sessions. Before the ‘Welcome Song’ was initiated, people living with dementia tended not to join in with the conversations that were going on around them unless they were asked questions. This perhaps indicated that they were less confident in communicating verbally. However, when using the communication tools that music afforded them, people living with dementia could engage in meaningful communication without the need for words. This enabled people living with dementia to have further agency within the sessions, connecting them to other people through a shared musical language. Some group members were able to sustain musical conversations (using the instruments to create ‘questions’ and ‘answers’ using rhythm and melody) far longer than verbal conversations. For example, Carol (living with dementia) lacked confidence in communicating verbally and yet was able to lead and engage with the practitioners, playing loudly and confidently, seemingly unafraid of entering musical encounters.

These moments of musical connection between the people living with dementia and other group members allowed them to develop new relationships or enhance the relationships they already had, such as the relationship between them and their spouse. The quote below highlights Mary's (living with dementia) view that musical communication made for a unifying experience:

You feel you are co-ordinating. It's a communication. You can see all of us when somebody plays this one, plays another one. That is communication. Accepting the music … that we are one because we want to make something good out of what we are doing.

Overall, this theme encapsulates the sense of connectedness experienced by the group through a shared musical language and a synchronicity in body experience. The ability of music to develop this sense of connectedness meant that the focus was placed on the creation of new music together, meaning there was little focus placed on the diagnoses held by people living with dementia but rather on a collective and cohesive group experience.

Observation 4: Musical ripples into everyday life

Although the primary aim of this research project was to understand the ‘in the moment’ experiences of people living with dementia when engaging in creative music-making, it became evident that there were ripple effects of sustained benefit outside the Music in Mind sessions. In the wider literature, the focus is often on whether a person living with dementia can remember the music session or has observable benefits in terms of the reduction of BPSDs. However, the findings from the data collected in this study gave a more intricate sense of the benefits that lasted outside the session, which included benefits at home, as well as in the wider community.

People living with dementia and their family carers were shown to find ways of extending their musical experiences outside the context of the Music in Mind sessions within their own homes. For example, Mary (living with dementia) purchased a digital radio so that she could listen to gospel radio stations. This may have been a result of her feeling a stronger sense of connectedness to her faith as she used the Music in Mind sessions as part of her own worship, introducing hymns and quoting bible passages. A further example was in the home of Henry and Jenny, where Jenny had bought Henry (living with dementia) a glockenspiel after observing his progress within the Music in Mind sessions on this particular instrument. Jenny had expressed concern in our second interview that Henry got bored very easily at home and acknowledged that making music was something that kept him engaged far longer than any other activity she had thought of before. Jenny may have seen the musical potential that Henry had through attending the sessions together, and then made changes to their home activities in order to keep Henry stimulated and engaged whilst at home.

This theme also highlights the ripple effects of experience taken by the person living with dementia into their wider communities. There was evidence of people living with dementia, and their family carers, becoming more involved in their wider communities as a result of taking part in the Music in Mind programme. For example, during one session, Carol and Richard brought leaflets with them advertising an exhibition at the Whitworth Art Gallery (part of The University of Manchester) called Beyond Dementia. As a result of this invitation, Jenny (family carer), Henry (living with dementia), Julie (family carer) and Scott (living with dementia) attended the exhibition and thus engaged with the wider arts community in Manchester. Jenny laughed when recalling their experience at the exhibition, telling me how Henry had become so entranced by a selection of music curated by people living with dementia that he became tangled in the headphones because he wanted to dance, forgetting that he had been wearing them:

We went to that thing at the Whitworth, that dementia thing, and he had it on then and it was somebody's playlist and he was listening to it and of course he gets up dancing in the Whitworth, forgot he was attached you know with [headphones].

This demonstrates how people living with dementia were able to engage with cultural activities that they had not engaged with before, perhaps seeking experiences similar to that held within the context of the Music in Mind programme.

Overall, this observation showcases the wider benefits of the Music in Mind programme outside the context of the sessions. It highlights that there was a desire for group members to keep engaged with music-making practices outside the sessions which promoted their inclusion within their wider communities.

Discussion

This article has presented an in-depth insight into the ‘in the moment’ musical experiences of people living with dementia using an embodied and sensory lens (Kontos, Reference Kontos2004, Reference Kontos2005; Pink, Reference Pink2015). The four thematic observations of Sharing a life story through music, Musical agency ‘in the moment’, Feeling connected ‘in the moment’ and Musical ripples into everyday life provide a contextual framework for ‘in the moment’ musical experience framed by the person living with dementia's life story and the experiences they take with them outside the boundaries of a music session. It is important to understand these ‘in the moment’ experiences within the broader music and dementia literature as it places a spotlight on the experiences held by the person living with dementia, enabling their musical stories to be told and valued. It also illuminates the processes involved within the context of musical engagement, rather than focusing on only pre- and post-intervention time-points. This provides a more detailed, person- and human rights-centred approach to understanding the wide range of benefits of music for people living with dementia, placing individual experience above collective change in predetermined outcomes (Kontos and Grigorovich, Reference Kontos, Grigorovich and Katz2019).

There is an emerging literature surrounding the contextualisation of life story using music (e.g. Kindell et al., Reference Kindell, Wilkinson, Sage and Keady2018). This literature differs from the more established literature surrounding the use of music for reminiscence purposes in that the main aim of the life-story work is not to evoke memories from the past, but rather to meet each person living with dementia where they are against a backdrop of their life. Much of the research which focuses on music for reminiscence purposes has strong cognitive narratives, with many studies seeking to understand whether music for reminiscence improves cognitive or neuropsychological outcomes (Kontos, Reference Kontos, Hyder, Lindemann and Brockmeier2014). This research has contributed to this growing literature surrounding the importance of contextualising musical experience with life story and has demonstrated the ability to learn key details about a person living with dementia's life through their interactions with music-making. It has also demonstrated the possibility of examining life story through an embodied lens in the context of music-making, enabling the experiences of people living with dementia to be studied through what was shown rather than having to rely solely on verbal narratives (Lyman, Reference Lyman1989; Kontos, Reference Kontos2004, Reference Kontos2005).

The Musical agency ‘in the moment’ observation showcased the wide range of musical skills in both contributing to improvisations as well as bringing performances to life through comedic gesture and facial expressions. Often, the creativity and skills of people living with dementia are overlooked in this area in favour of an understanding of changes in BPSDs. However, there is a growing body of research which has begun to explore the creativity of people living with dementia (e.g. Killick, Reference Killick, Clarke and Wolverson2016; Bellass et al., 2018; Zeilig et al., Reference Zeilig, West and van der Byl Williams2018). The term ‘creativity’ is often reserved for those who are labelled ‘creative individuals’ or ‘creative geniuses’ which in turn contributes to misconceptions of what it means to be creative. These interpretations are in line with the concept termed ‘Big-C’ creativity which appears reserved for those who are particularly ‘gifted’, making the concept unlikely to be associated with people living with dementia (Kaufman and Beghetto, Reference Kaufman and Beghetto2009).

However, the growing body of work which is emerging in recent years supports the importance of ‘little-c’, or everyday creativity, being showcased by people living with dementia (Bellass et al., 2018). This was observed within the context of this research study, with people living with dementia showing improvisatory creativity both in the music they improvised and the ways in which they used their embodied practices to construct musical stories through gesture and facial expression. In the academic literature, the retaining of musical skill and creativity is often reserved for those who had been viewed as ‘Big-C’ creatives in their lifetimes (e.g. concert pianists). Many of these case studies report areas of the brain relating to retained musical ability being ‘spared by dementia’ rather than considering the role that embodied and sensory life experience may contribute to the retaining of skills for people living with dementia (Kontos, Reference Kontos, Hyder, Lindemann and Brockmeier2014). Thus, by taking an embodied and sensory approach to understanding creativity in the context of music-making it will be possible to move beyond the cognitive narratives of ‘Big-C’ creativity and towards a system that values ‘little-c’ creativity and the benefits it engenders for people living with dementia.

The Feeling connected ‘in the moment’ observation demonstrated the relational nature of music-making, with people living with dementia showcasing an enhanced connection to the music-making space (e.g. recognising the space as being a place to make music) as well as to other members of the group. This sense of connectedness was afforded through shared bodily experiences (i.e. synchronisation) as well as music being used as a non-verbal language through which to convey musical stories, emotion and humour. The power of music in creating and facilitating this connectedness both with people and place is well documented within the music and dementia qualitative literature (Kontos, Reference Kontos, Hyder, Lindemann and Brockmeier2014; McDermott et al., Reference McDermott, Orrell and Ridder2014; Dowlen et al., Reference Dowlen, Keady, Milligan, Swarbrick, Ponsillo, Geddes and Riley2018), with this research pointing to this sense of connectedness contributing to feelings of security, equality and companionship. Of course, the power of connectedness that music can facilitate through embodied action is not unique to people living with dementia, with Bowman and Powell (Reference Bowman, Powell and Bresler2007: 1099) suggesting that ‘bodies in states of music are multiply sensed and strongly connected to the world’. However, as is well documented with the wider dementia studies literature, the experience of dementia can be quite isolating and can result in feelings of loneliness for the person themselves as well as their family carers (Harris and Keady, Reference Harris and Keady2004). Thus, engagement with music provides an opportunity to create connections through ‘in the moment’ musical interaction which is not reliant on verbal communication or cognitive capacities.

The final observation, Musical ripples into everyday life, illuminated the ways in which the benefits of the Music in Mind programme lasted outside the context of the music-making space. Using an embodied and sensory approach to understanding the benefits of music enabled a more nuanced interpretation of how Music in Mind extended into the everyday lives of the group members than a typical pre/post-intervention measurement of symptoms may have afforded. There is, thus, further work that needs to be done to understand the ripple effects of taking part in music programmes, such as Music in Mind, in order to build a more holistic picture of the sustained impacts of taking part in such programmes for people living with dementia. This is a particularly pertinent way of understanding the lasting benefits of music for people living with dementia as many programmes, with Music in Mind included, are not indefinite and are often structured around funding for a given number of sessions in a given time period. This is a challenge that is not unique to understanding the benefits of music for people living with dementia and is something that warrants further exploration within cultural programmes that seek to address health and wellbeing needs (Dowlen, Reference Dowlen2020).

Although the aim of this study was to explore ‘in the moment’ experiences, it provides potential for the development of ripple effect outcomes which could be examined further in order to understand the ways in which people living with dementia may be empowered to engage with arts, culture and heritage more broadly as a result of taking part in music programmes.

Study limitations

It must be acknowledged that while the goal of case study research is not to build generalisable findings, the sample size in this study was small and conducted within a very specific musical context (Music in Mind). The in-depth nature of the study allowed for the exploration of ‘in the moment’ embodied and sensory experiences, but it is not clear whether these findings would extend beyond the study participants. There is, thus, clearly scope to develop these themes further in the context of a larger sample and different musical context in the future.

Secondly, due to the focus of this research being ‘in the moment’, there was no formal follow-up with participants to examine the longer-lasting impacts of having taken part in the Music in Mind sessions. The sense of connection that had been felt by group members meant that the final session was both a celebration and a ‘goodbye’ for many of the group members who no longer had the weekly opportunity to meet with the friends they had made in the group. Following-up with participants later down the line may have given more insight into the lasting benefits or challenges experienced by participants as a result of no longer having weekly sessions to attend. It would have also provided opportunity to examine the ‘ripple effects’ of cultural participation in the everyday lives of participants. This is something that future work examining the impacts of music for people living with dementia should explore further.

Finally, the sample was predominantly made up of those living with a young onset dementia who were living in the community and so further examination of the applicability of these findings to other groups of people living with dementia, including those living in care home settings, would be important going forward.

Conclusion

This study sought to gain an in-depth understanding of the ‘in the moment’ embodied and sensory experiences of people living with dementia engaging in a participatory music-making programme (Music in Mind). Overall, the findings from this research showcase the creativity and musical abilities of people living with dementia whilst affirming music as a medium to connect people living with dementia with their own life story, other people and the environments in which music-making takes place. This points to the strengths of using embodied and sensory approaches to understand ‘in the moment’ musical experience, enabling the lived experiences of people living with dementia to be central in understanding the benefits of music rather than on the periphery, as is so often the case.

This has implications for research going forward, showcasing the need to not only focus on BPSDs but to capture experiences in a more holistic way which centralises the experiences of people living with dementia ‘in the moment’. While this is the first attempt to examine such ‘in the moment’ experiences formally, it is clear that more theoretical development is required in understanding ‘moments’ in the context of dementia. There may also be rich benefits in adopting a moments-based approach in other areas within dementia studies as it may enable a more person-centred approach to understanding the experiences and embodied storytelling of people living with dementia.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for their contribution to this work.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Social Care Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/IEC08/0049).