Introduction

Like the rest of the developing world, the United Kingdom (UK) is experiencing demographic change. There are currently 12.4 million people aged 65 or over in the UK and over 1.6 million are aged over 85 (Office for National Statistics, 2020). Up to two-thirds of those aged over 85 have a disability or limiting long-term illness (Age UK, Reference Age2019).

Whilst food security and the UK food system itself are relatively secure (Economic and Social Research Council, 2012), the potential for older people to become vulnerable could be influenced by a number of factors, though no research has explored these in detail in relation to the older population (GreenStreet Berman, 2011). Thus, food insecurity might disproportionately affect older people through factors such as access to a car (Coveney and O'Dwyer, Reference Coveney and O'Dwyer2009), living in an urban versus rural environment (Whelan et al., Reference Whelan, Wrigley, Warm and Cannings2002), bereavement, social isolation (Fjellström et al., Reference Fjellström, Sidenvall, Nydahl, Frewer, Risvik and Schifferstein2001), design (Maguire et al., Reference Maguire, Peace, Nicolle, Marshall, Sims, Percival and Lawton2014) and technological competence. Age and cohort effects could differentially influence how food is chosen, perceived and used by older people (King et al., Reference King, Orpin, Woodroffe and Boyer2017). Deterioration in sensory perception could put older people at increased risk of food-borne illness (Dickinson et al., Reference Dickinson, Wills, Meah and Short2014). Sixsmith et al. (Reference Sixsmith, Sixsmith, Fänge, Naumann, Kucsera, Tomsone, Haak, Dahlin-Ivanoff and Woolrych2014) suggest that once older people can no longer prepare their own food they feel inherently more vulnerable through loss of autonomy. Given these demographic shifts, and that vulnerability is acknowledged to be socially constructed and therefore inherently unequal in terms of the ways and degree to which someone is at harm, Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti (Reference Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti2006) suggest the importance of exploring the processes associated with vulnerability. Thus, paying closer attention to food insecurity from the perspectives of older people themselves is required. A better understanding of vulnerability,can identify where action is needed to address the factors moving people towards it. This could improve quality of life for individuals, lead to better public health outcomes through reduction in the burden of disease and disability, demand on health and social care services and ultimately economic benefits.

Food insecurity

Food insecurity is defined as ‘the inability to consume an adequate quality or sufficient quantity of food in socially acceptable ways, or the uncertainty that one will be able to do so’ (Dowler and O'Connor, Reference Dowler and O'Connor2012: 45). Food security is a critical issue for public health (Purdam et al., Reference Purdam, Garratt and Esmail2015), as well as health and social care policy and practice. In the UK, increasing concern with food insecurity in later life resulted in the establishment of an All-Party Parliamentary Group inquiry into hunger and malnutrition in older people which published its first report in 2018 (All-Party Parliamentary Group on Hunger, 2018), noting a lack of robust data on the numbers of older people affected. Food security in later life is a public health issue in other developed nations, including the United States of America (USA) (Strickhouser et al., Reference Strickhouser, Wright and Donley2015), Australia (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Flood, Yeatman and Mitchell2014) and South Korea (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Park and Kim2019). Strickhouser et al. (Reference Strickhouser, Wright and Donley2015) found that all population groups in the USA could experience food insecurity and this affected 24 million people, including one in eight people aged over 70. This had an effect on health indicators, with those affected more likely to report living with diabetes, depression, disability or generally poor health. In Australia, 3 per cent of those aged over 75 report food insecurity, with women and men living alone, those on low income and those with multiple long-term conditions being most at risk (Temple, Reference Temple2006). Food security clearly is an important issue worthy of academic attention.

Food insecurity among older people

There are few studies of food security among older people in the UK. Purdam et al. (Reference Purdam, Garratt and Esmail2015) undertook secondary analysis of large datasets, including the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing and the Health Survey for England. This analysis found women were twice as likely to be malnourished as men and over half of those who were malnourished had a limiting, long-standing illness. Financial concerns contributed, with lack of money affecting food-purchasing choices; others reported not receiving the help they needed to prepare and eat hot meals. Purdue et al. (2015) examined the 2012 UK Adult Social Care survey of adults receiving social care in their own homes and found that 4.3 per cent reported that they did not always have adequate or timely food. A recent report found that 1.9 million older people in the UK live in poverty, with increases in levels of poverty in old age largely affecting those living in rented accommodation (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2018).

Factors specifically contributing to the food security of older people have been identified by the UK Malnutrition Task Force (2017). These include the inability to shop for food; 18 per cent of people aged 60–69 years and 38 per cent people aged over 70 have a mobility difficulty, and over 2 million people aged over 65 live with sight loss, making shopping challenging. They reported that access to food outlets can be problematic; 11 per cent of people aged over 65 have difficulty accessing a corner shop, 12 per cent find it difficult to get to their local supermarket and 28 per cent of rural households do not have access to a supermarket within 4 kilometres. A questionnaire-based study exploring factors affecting food choices across eight European countries (Dean et al., Reference Dean, Raats, Grunert and Lumbers2009) found material resources, such as income and access to a car, influenced the variety of foods eaten. Links have been reported between food insecurity in older age and poorer physical and mental health outcomes, including stress, depression and self-reported health (Hampton, Reference Hampton2007; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Flood, Yeatman and Mitchell2014; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Park and Kim2019). Social isolation and loneliness can lead to malnourishment in older people, with rates of loneliness in Western countries varying between 5 and 10 per cent in people aged 65+ (Victor and Bowling, Reference Victor and Bowling2012).

Causes of food insecurity include macro-structural issues such as global and national food production and food safety, and local factors such as the availability and types of food outlets in a neighbourhood (Elia and Stratton, Reference Elia and Stratton2005; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Donley, Gualtieri and Strickhouser2016; Wills et al., Reference Wills, Danesi, Kapetanaki and Hamilton2018) and access to transportation (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Flood, Yeatman and Mitchell2014). At a household level, income, knowledge and skills, including the ability to budget for and cook food, influence food security (Dowler et al., Reference Dowler, Kneafsey, Lambie, Inman and Collier2011).

Household food insecurity in younger and older people share common contributing factors, including personal factors (income, health, homelessness) as well as systemic factors (price and availability of food, access to support) (Food Foundation, 2016). However, the way that older and younger people deal with these factors may differ as older people are generally more likely to suffer from illnesses that affect their ability to respond to challenges (Strandberg et al., Reference Strandberg, Pitäklä and Tilvis2011). Younger people are more likely to have a larger support network of family and friends and access to school meals. Older people are more likely to experience isolation and loneliness (Gabriel and Bowling, Reference Gabriel and Bowling2004). In addition, people in later life face substantial inequalities often acquired across their lifecourse (Calder et al., Reference Calder, Carding, Christopher, Kuh, Langley-Evans and McNulty2018). These studies have focused on particular elements of food insecurity but fail to examine how this affects the daily lives of older people.

Food security and malnutrition

Prolonged food insecurity can lead to malnutrition (Food Foundation, 2016). It is estimated that 1.3 million older people are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition in the UK alone (Malnutrition Task Force, 2017). Malnutrition results from several factors acting in isolation or combination, including lack of affordability and availability of food, poor food-related knowledge and skills, lowered or deteriorating physical or mental health status, cognitive function and social isolation, and issues such as swallowing difficulties (Fjellström et al., Reference Fjellström, Sidenvall, Nydahl, Frewer, Risvik and Schifferstein2001; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Conklin, Suhrcke and Monsivais2014; Abdelhamid et al., Reference Abdelhamid, Bunn, Copley, Cowap, Dickinson, Gray, Howe, Killett, Lee, Li, Poland, Potter, Richardson, Smithard, Fox and Hooper2016). Malnutrition has consequences for the individual, affecting health, morbidity and mortality (Morley, Reference Morley2018). At a macro level, malnutrition has major economic implications: the estimated cost of malnutrition to the UK health and social care system was £23.5 billion in 2017, with malnutrition in older people accounting for over half of this cost (Stratton et al., Reference Stratton, Smith and Gabe2018). It is important to understand more of how food insecurity leads to malnutrition so that earlier interventions can be made.

Vulnerability and ageing – a predictive model

Schröder-Butterfill (Reference Schröder-Butterfill2012: 1) argues that vulnerability as a term ‘is often employed as an ill-defined descriptor of people or groups who are in some way disadvantaged’ and often used as shorthand to describe those within the older population who are frail or dependent (Chambers, Reference Chambers1989; Schröder-Butterfill, Reference Schröder-Butterfill2012). Lack of clarity means it is hard to operationalise or analyse vulnerability in any systematic way (Zaidi, Reference Zaidi2014; Virokannas et al., Reference Virokannas, Liuski and Kuronen2020). Therefore, in this paper, we define vulnerability to food insecurity as:

the incremental outcome of a set of distinct but related risks, namely: the risk of being exposed to a threat, the risk of a threat materializing, and the risk of lacking the defences to deal with a threat. (Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti, Reference Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti2006: 11)

There are several models of vulnerability, emerging from a range of disciplines. The academic literature on vulnerability and older age has been explored by a number of authors (e.g. Baker et al., Reference Baker, Gentry and Rittenburg2005; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Scully and Hart2014; Zaidi, Reference Zaidi2014). The Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti (Reference Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti2006) model has its origins in geography, in particular, studies of natural disasters, where it was noted that risk of harm is socially constructed, thus not all people were affected equally. Burghardt (Reference Burghardt2013: 558) notes that recent scholarship within the field, while accounting for the complexity and multi-faceted nature of vulnerability, has moved away from a focus on the individual, to deconstruct and examine ‘socially constructed forces that contribute to its manifestation’. In this paper, we apply this framework to the issue of food security.

The Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti (Reference Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti2006) vulnerability model is comprised of four domains: exposure, threats, coping capacity and bad outcomes.

Exposure is based on understandings gained from lifecourse approaches where factors carried forward from earlier parts of the lifecourse affect vulnerability in older age (Calder et al., Reference Calder, Carding, Christopher, Kuh, Langley-Evans and McNulty2018). These include structural factors such as education, employment history, income and marital status, which influence the resources available in older age. Living and financial arrangements influence eating practices, e.g. men living on their own may lack skills in cooking and shopping, have poorer social networks and are more likely to resist interventions for help (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bennett and Hetherington2004; Grundy, Reference Grundy2006; Kullberg et al., Reference Kullberg, Björklund, Sidenvall and AC2011). The financial benefits of an occupational pension affect the ability to purchase healthier foods (Munoz-Plaza et al., Reference Munoz-Plaza, Morland, Pierre, Spark, Filomena and Noyes2013). The second domain, threats, is defined as ‘specific events, shocks or crises’ (Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti, Reference Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti2006) that move people towards a bad outcome. Major events include stroke, falls or bereavement. Thirdly, the domain of coping capacity describes the assets people draw on to protect themselves from ‘bad outcomes’ or the adaptations that help them recover. This domain was later elaborated (Schröder-Butterfill, Reference Schröder-Butterfill2012) to include ‘individual capacities’, ‘formal support’ and ‘social networks’. This domain incorporates the notion of human agency, while acknowledging that the challenges associated with responding to vulnerability include relational aspects such as support from social networks, and formal support. The final domain, bad outcomes in relation to food insecurity could range from poor health and wellbeing, to morbidity or mortality from malnutrition (Temple, Reference Temple2006; Morley, Reference Morley2018).

This predictive orientation of the model enables us to consider how and where interventions to increase coping capacity or resilience can be targeted to prevent progression to a bad outcome (Handmer, Reference Handmer2003; Schröder-Butterfill, Reference Schröder-Butterfill2012). This forward-looking and dynamic aspect makes the framework useful for those seeking to address food insecurity, helping us understand the way that threats are operationalised. The model helps to challenge understandings of vulnerability and resilience, how they impact on people's lived experience and how they are shaped by policy (Hutcheon and Lashewicz, Reference Hutcheon and Lashewicz2014).

Vulnerability to food security: a social practices approach

Acquiring, preparing and eating food are routine, embedded aspects of everyday life and form part of an overall practice of ‘doing’ food, rather than rational, conscious or individual actions. Such tacit practices are shaped throughout the lifecourse according to the social structures that underpin society. Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1984) refers to such practices as being part of the habitus, as having a ‘feel for the game’ when it comes to repeatedly getting, cooking or eating food according to social distinctions that are an ingrained part of ‘the way we live’. The action of buying, growing or eating food, when viewed as part of a practice, encompasses an intertwined set of knowledges, relationships, values, beliefs, resources and technologies that interconnect to form a food practice. People are ‘carriers of practices’ (Reckwitz, Reference Reckwitz2002), no more or less important than the other strands that form a practice.

Practices have three components: competency (the skills and know-how that is drawn upon), materiality (objects and technologies that are used in the performance of the practice) and meanings (ideas, norms and symbolism shaped over the lifecourse) (Shove et al., Reference Shove, Pantzar and Watson2012). In this study we are interested in all components of food practices – including how a practice is performed or ‘carried’ by the participant, how practices might change, what might prompt the change and the effect this has on the older person. Shove et al. (Reference Shove, Pantzar and Watson2012: 14-15) argue that ‘practices emerge, persist, shift and disappear when connections between elements are made, sustained or broken’. This dynamic understanding of practices guided this study towards understanding vulnerability to food insecurity. The three components of practices were used to guide and underpin data collection and analysis; they are different but complementary to the four concepts that comprise the vulnerability model we are using. We chose to use practice theory to help exemplify the four domains of the vulnerability model. For example, competency and materiality in relation to food practices illustrate household coping capacity, through demonstrating the assets drawn on and the adaptations made, to avoid or move towards vulnerability to food insecurity. The meanings associated with a food practice can provide insight into a household's exposure to lifecourse events and structural determinants. Meanings provide insight into how the habitus is shaped.

In earlier work, we explored how the performance of practices within the domestic kitchen could either protect or propel an older person towards vulnerability in terms of food-borne illness (Dickinson et al., Reference Dickinson, Wills, Meah and Short2014). Jackson and Meah (Reference Jackson and Meah2018) drew on this and other studies to explore vulnerability in relation to food-borne illness, concluding that vulnerability is situational, contextual and dynamic. They argue that vulnerability goes beyond the conceptualisation provided by Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti (Reference Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti2006), and call on ‘authorities to develop a more nuanced understanding of vulnerability’ (Jackson and Meah, Reference Jackson and Meah2018: 91) to develop and target public health interventions better. However, they fell short of providing a practical model that could support policy makers and practitioners to achieve these ends better and the present study therefore seeks to address this gap. There is a need for empirical studies that analyse the determinants of vulnerability in later life (Schröder-Butterfill, Reference Schröder-Butterfill2012) and household food insecurity (Food Foundation, 2016), to which this study contributes.

Using social practice theory enabled us to shift the focus of inquiry away from what an individual ‘does’ to make themselves vulnerable to focus on and think about people as ‘carriers of practices’, to explore how and why practices change in older age in order to highlight where and how vulnerability to food insecurity is manifested. This study develops the understanding of vulnerability to food security, through drawing on practice theory, bringing together two theoretical frameworks to explore the dynamic nature of vulnerability (how it might begin, worsen or be eased) and enable a more nuanced understanding of how this is experienced in the everyday lives of older people.

Study aim

The aim of the study was to explore how vulnerability to food insecurity affects everyday food practices in later life.

We use findings from the study to develop a model for national and local policy makers to help them to identify areas where interventions could be effectively targeted.

Methodology and methods

A previous study by the authors (Wills et al., Reference Wills, Meah, Dickinson and Short2015, Reference Wills, Dickinson, Meah and Short2016) successfully operationalised a methodological approach that could capture and analyse social practices, and the current study develops this methodology further. Within the social sciences there is a move to ‘switch frames from health behaviours to health practices’ (Twine, Reference Twine2015) to understand better everyday and mundane practices and their relationship to health-related outcomes. As we resisted the label of vulnerability as an uncontested or individualised notion, a way of exploring this concept without asking people to identify themselves as vulnerable was used. We did not presuppose what vulnerability to food insecurity might look like or who might be vulnerable. Using theories of practice within an ethnographic approach (Hammersley and Atkinson, Reference Hammersley and Atkinson2007) enabled us to explore in depth the everyday food practices of older people (Maller, Reference Maller2015). Within the research design we employed a ‘bricolage’ of methods (Denzin and Lincoln, Reference Denzin, Lincoln, Denzin and Lincoln2005; Mannay, Reference Mannay2016), deployed over several household visits that supported participants to engage flexibly with a range of methods at a pace that suited them (Mannay, Reference Mannay2016).

The fieldwork began with tours, led by the participants, of areas of their household associated with food, generally beginning with the kitchen and an exploration of kitchen cupboards, fridges, freezers and work surfaces. Garden sheds, gardens and allotments were included if people grew their own food or herbs, and these spaces were captured in photographs and/or video. Semi-structured interviews were conducted, guided by a topic guide, during each household visit and these were audio-recorded. ‘Go-along’ tours were conducted of places where food acquisition occurred outside the home and were captured using wearable video cameras (most participants preferring the researcher to wear the camera). Tours included shopping trips, visits to lunch clubs and coffee mornings, ordering food from catalogues and receipt of meals-on-wheels. This enabled researchers to observe participants as they enacted part of a food practice, giving an insight into interactions with the food environment. We could experience with households the supermarket or shop, routes taken, and proximity to bus routes or car parking.

Visual methods enabled us to capture how people used material artefacts (e.g. shopping bags and trolleys), buildings (which features of the supermarket supported or hindered them), other environmental factors (space, noise, obstacles) and use of their own physicality (carrying, bending and stretching to reach food items). Video-recording allowed repeated playback and observation by all members of the research team, as well as playback to participants to gain additional insights and clarification during subsequent interviews (Pink, Reference Pink2007).

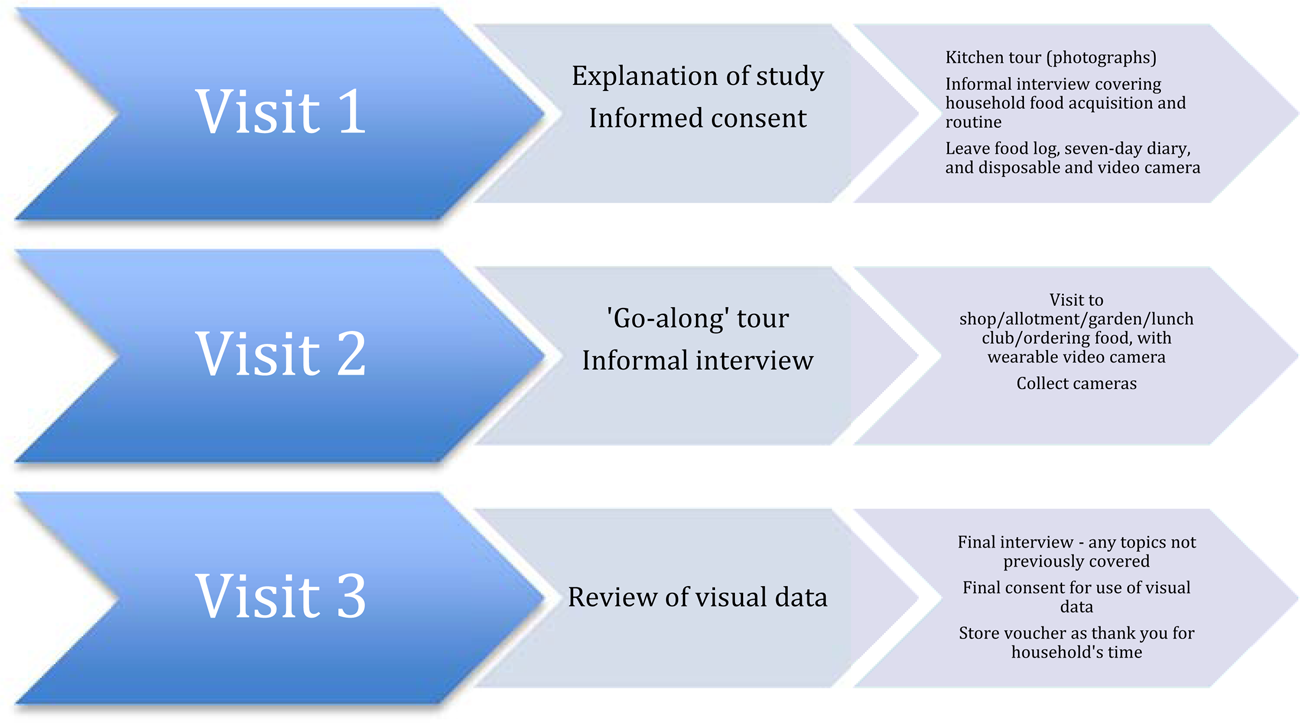

Whilst Schatzki et al. (Reference Schatzki, Knorr Cetina and Von Savigny2001) caution against an over-reliance on verbal ‘sayings’ and instead urges priority towards ‘doings’, it is nonetheless important to hear people's accounts and explanations for their actions. During the ‘go-along’ tours, participants were encouraged to provide a narrative of what they were doing, prompted by questions from the researcher accompanying them (Pink, Reference Pink2007). What was important to us was understanding the overall practice, brought to the fore through the equal contribution of all forms of data collected. Our methods are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Data collection – summary.

The ‘go-along’ tour was piloted with a member of the University of Hertfordshire's Public Involvement in Research Group, which enabled the researchers to ‘practise’ using the technology. A short film was produced to illustrate to potential participants what involvement in the study would mean.

Analysis

The data collected amounted to 50 interview transcripts, 1,270 photographs, 23 hours of film, 20 food logs/notes from participants and 25 sets of fieldnotes. Analysis of the data built on an interpretative engagement approach successfully used in our previous study (Wills et al., Reference Wills, Dickinson, Meah and Short2016). All interview data were transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Photographs and video data were viewed and notes were made about the content. A preliminary exploration of the data involved all members of the team familiarising themselves with the full datasets from specific households. All data sources for a household were read (transcripts, fieldnotes and food logs) and viewed (photographs and video) before being discussed by the team.

Following this initial analysis and identification of emergent themes, a summary of themes for each household was produced. Each summary was produced in a consistent manner to support cross-household analysis. The analysis suggested four overarching themes: the food environment, social aspects, physicality and mental/emotional processes involved. For each of these four themes, four sub-themes were used to identify data relating to assets used by households, relevant lifecourse events, obstacles or threats households were exposed to, and adaptations. These themes identified practices operating at different levels of the food system, e.g. the wider food environment (availability, proximity and choice of local shops and supermarkets), social networks, the physical (e.g. transportation of food to the home, growing food), emotional and mental work (planning what to buy and household budgeting) undertaken. These four sub-themes were informed by and related closely to the domains of the Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti (Reference Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti2006) framework.

Cross-household analysis was then undertaken, with contrasting data examples (e.g. comparing experiences of households living alone with those with couples or living with adult children), pivotal moments (the impact of events such as bereavement) or points of change (forming new relationships). Textual data were coded in NVivo version 11 computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (QSR International, Melbourne) to support data management and retrieval.

A minimum of two authors engaged with data for each household and the entire dataset was reviewed by two authors. Any differences in interpretations of the data were discussed at meetings with the whole research team throughout the analysis phase.

Participants

In order to recruit a diverse sample of older people aged 60 and above, contact was made with organisations representing older people and service providers such as meals-on-wheels services, lunch clubs, charities and sheltered housing associations. Purposive sampling was used to target particular groups of people and ensure different household types were invited to participate. The 25 households recruited included people living with a spouse, alone or with other family members; a diversity of ages from 60 to 93 years; people independent in food provisioning, and those in receipt of assistance from informal and formal sources. Participants lived in urban as well as rural areas.

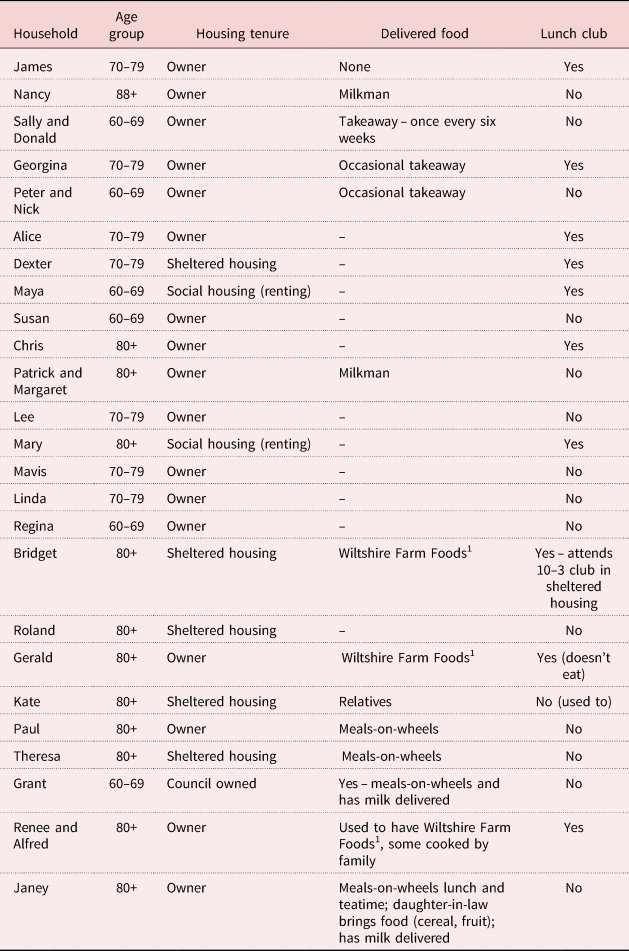

Table 1 summarises relevant demographic data for each household.

Table 1. Summary of households

Note: 1. Commercial supplier of frozen ready-meals delivered to the home to be reheated in the home.

Findings

Findings relating to the domains of the vulnerability framework are presented below, structured to explore practices that occur outside and then within the home. As Zaidi (Reference Zaidi2014) cautioned, and in line with analysis of social practices, we found when analysing the data that determining which of the domains of vulnerability the data fitted within was sometimes difficult and arbitrary due to their ‘entangled’ nature as they played out within the complexity of people's lives. Often, multiple threats were in play at the same time, requiring households to draw on a range of assets and make multiple adaptations in response, thus depleting their coping capacity. In addition, one adaptation could be used to address a number of threats successfully, e.g. being in receipt of a meals-on-wheels service alleviated food insecurity through providing food but could also help to address social isolation. One of the main features revealed within the data was the cumulative nature of the threats found to be operating both within and external to households.

Consideration of the concept of cumulative trivia (Newall et al., Reference Newall, Dewar, Balaam, Porter, Baggaley, Murray and Gilloran2006) added to the understanding of vulnerability as experienced by participants. Cumulative trivia are defined as a ‘continual accumulation of small, individually minor events or difficulties that degrade their resilience until they cannot cope with another thing’ (Newall et al., Reference Newall, Dewar, Balaam, Porter, Baggaley, Murray and Gilloran2006: 331). The crucial aspect of these trivia is that if they were considered individually they would not lead to a crisis (Newall et al., Reference Newall, Dewar, Balaam, Porter, Baggaley, Murray and Gilloran2006). The magnitude of effect of a growing number of seemingly small threats moved households towards vulnerability. These included embodied threats such as a gradual decline in mobility over time as well as structural threats experienced outside the home, including physical obstacles within supermarket aisles and the availability of suitable toilet facilities within shops. We illustrate this cumulative impact and the domains of vulnerability firstly by presenting a case study of Dexter, where we examine the evolution of food practices within one household. Handmer (Reference Handmer2003: 58) noted that assessment of vulnerability is immensely complex and shifting, with aspects critical to coping often being ‘dormant or invisible’ until circumstances change. Drawing on a case study enables us to show some of this complexity. We illustrate how emergent threats demand a response. Adaptations are made, demonstrating Dexter's coping capacity as he mobilises resources in reaction to changing events. The components of coping capacity, adaptations and assets are highlighted using parentheses throughout the case study. Assets include social capital and social networks, including the skills, confidence and know-how to support the creation of new (emergent) networks. We highlight the meanings associated with Dexter's food practices in the narrative, to demonstrate the emotional aspect or state of mind associated with some of his food practices, meanings that arise and are shaped through lifecourse events to which Dexter has been exposed. Following this case study of Dexter, we present further data illustrating some of the challenges to vulnerability faced by other households, to explore how practices in later life are formed and then influenced by threats and coping capacity and how these influence experiences of vulnerability.

Dexter: a case study

Dexter lives on his own in a ground-floor, rented sheltered housing flat that he moved to some years ago to be nearer to his sister (adaptation). Before he retired he enjoyed driving and worked as a chauffeur (exposure) but has given up driving due to his deteriorating vision following onset of macular degeneration (threat). He has several health issues that have had a major impact on his food-related practices and habitus, including cardiovascular disease and about five months prior to the study ‘go-along’, he fell and damaged his knee (threats).

Vulnerability inside the home

Following a stay in hospital, Dexter became housebound and reported feeling lonely (threat). Dexter has drawn on a number of assets to support a series of adaptations. He has drawn on his know-how to contact a local charity that helped him find a carer – Jason now visits three or four times per week to help with shopping and cooking, and a friendship has developed as the two men share several interests (adaptation).

Dexter enjoys cooking (exposure, meaning), however, limited eyesight and inability to stand for long periods have affected his ability to prepare meals (threat), therefore, he has a chair in the kitchen so he can rest (adaptation). He has accidentally cut himself several times (threat), so now buys sliced bread and frozen vegetables to avoid the need to use sharp knives (adaptation). The food in his cupboards is carefully organised so he can find them despite his failing eyesight, and he has tactile markers on the dial of his microwave (adaptation). A major change in Dexter's food practices relates to eating and entertaining. He used to enjoy hosting dinner parties for friends (exposure, meaning) but is no longer able to do this (threat). He and Jason cook together and share meals (adaptation). Jason has become part of Dexter's emergent social network. Dexter is proud that he still cooks a roast dinner, using leftover meat to make sandwiches. He cooks soup that he then stores in his fridge or freezer to use later (adaptation). Dexter tried meals-on-wheels when he came home from hospital but did not enjoy the food.

Vulnerability outside the home

Dexter's declining eyesight affects practical aspects of his food practices, particularly his shopping competency; he described struggling to find the food he wants to buy on the supermarket shelf (threat):

…many a time I pick something up, got it home I thought ‘what's this?’ and I get me magnifying glass, ‘oh I don't want this’. So that's why I, you know, get somebody to come with me now. I can't see what I'm picking up now so therefore I, you know, see what annoys me is with these supermarkets first of all you go in a supermarket, it's the same map and everything so alright, I can pick that up, no trouble at all, but then they move it … course then it takes me half an hour to get one item.

Dexter used to travel by bus to his preferred supermarket where ‘the staff are more friendly’ and he had a good relationship with one of the checkout staff (meaning). He cannot manage the step on to the bus now (threat), so shops at a different supermarket, walking there with Jason (adaptation); but it is not where he would choose to shop (exposure, loss of meaning). He worries what might happen if he falls again (threat). Video footage of Dexter shows him being forced to walk in the road because of cars parked on the pavement (threat). Dexter shops on Wednesdays, when it is quieter, ‘If you go on a Friday you get pushed and shoved and … I just got fed up with that’ (adaptation). He describes the supermarket as an ‘obstacle course’ (threat) and we observed him being steered around numerous obstructions in the aisles by Jason (adaptation). His walking aid with a seat enables him to rest at points around the store (adaptation).

Jason helps Dexter find the items he wants to buy, checking packaging information (Dexter is particularly conscious of adhering to use-by dates), helping at the till and packing food into the trolley (adaptation). Dexter feels he lacks agency to change things (threat). He felt it was a waste of time to talk to managers to complain about poor customer service (threat): ‘there's no point … Nothing gets done, it's still the same’.

He attends a lunch club locally, originally to make friends (adaptation and creation of new social networks). However, some of the people who attend bring alcohol and drink all afternoon, which Dexter is uncomfortable with (threat).

In summary, through exploring one case study, we can see how a number of threats, both major (health-related due to declining eyesight and mobility) and minor (e.g. lack of seating at the supermarket) individually and cumulatively propel Dexter towards a more vulnerable state. Threats constantly challenge Dexter to respond, resulting in adaptations to his food practices that move him away from food insecurity. Some of the adaptations made, although appearing to address the threats, drew from his assets but were at the expense of other aspects of his wellbeing, as they change the meaning of a practice. For example, although Dexter is still able to obtain food, the food he cooks has changed and it is not purchased from his preferred supermarket (loss of meaning). Some social enjoyment of food is restored by emergent social networks that provide relationships, enabling him to share meals with Jason and by attending a lunch club. For Dexter these are involuntary changes to his practices. The adaptations are partial in terms of supporting his habitus; responding to each challenge enables him to cope, but by doing so, he loses the agency and meaning he has built up throughout his life.

Vulnerability and food security

The challenges described in the case study were not unique to Dexter and threats to food security were numerous and evident both inside and outside the home for many study participants. In the following sections, we consider other issues we found affecting food security within the home (private spaces) and outside it (public spaces). Threats were experienced in relation to changes in health, loss and bereavement, and transportation. Food packaging could add additional threats to practices, with some participants describing difficulty removing lids from jars, etc. We also explore the social aspects related to food shopping practices and community food assets used by our participants.

Food practices for many people were well established, having been created over the lifecourse, and gradually changing in response to new household exposures such as children leaving home. Maton (Reference Maton and Grenfell2012: 49) explains that though there are no ‘explicit rules dictating such practices’, nevertheless social practices have ‘regularities’ which make them recognisable, as part of the habitus. Therefore, many experiences highlighted by our data were shared across households. Households reflected on changes in the food landscape over their lifetimes, noting the decline of local butchers and greengrocers, and their transition to reliance on larger supermarkets. All households ate at least some food acquired from supermarkets, though for some, the actual purchasing could be done by proxy by other actors in their social network, e.g. via a family member (Kate), neighbour (Paul) or paid carer (Bridget). Food from gardens and allotments (Linda), markets and local shops supplemented supermarket purchases for some people (Grant, Nancy). Others acquired food via restaurants and pubs, with smaller numbers having food delivered from milk-delivery services (Janey, Grant), takeaway shops, specialist frozen-meal providers targeting older consumers (Gerald), as well as food from meals-on-wheels services (Grant) or prepared by families (Georgina).

Many older households paid little conscious thought to how these routines had become established and could be seen to be displaying what Bourdieu describes as an inherent feel for the ‘rules of the game’ (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1984). The ultimate objective of the ‘game’ was to provide meals that were socially acceptable to members of the household. thereby not disturbing the meaning of the practice.

Health-related threats to food practices

Onset of physical or mental illness precipitated changes to food practices for many participants. As Warde (Reference Warde2016: 43) notes, ‘complex practices are complex precisely because of their internal variety’ and a broad range of health conditions threatened people's coping capacity to undertake activities across the spectrum of food practices. Both duration and severity of illness affected the impact on food practices, e.g. the dietary management of diabetes and raised cholesterol required ongoing changes to the food eaten whereas undergoing a planned operation in hospital had a shorter-term and different impact. Co-morbidity and progression of conditions added additional layers of complexity and impact. The existence of health conditions was evident in participant's kitchens; many of the photographs of the contents of kitchen cupboards, drawers and worktops showed stocks of medication stored alongside food items. Material objects such as perching stools, walking aids and shopping trolleys were often kept in kitchens, to enable participants to adjust and accommodate a health condition or changes to mobility.

Mobility issues were a key factor affecting the ability of households to undertake food practices inside and outside their home. Kate had changed her food practices as her mobility declined following major surgery (threat). She uses a walking frame but is now only physically able to prepare snacks rather than meals: ‘I can do that (make snacks) and I make cups of tea and things like that’. Her daughter, who lives locally, has taken over buying and preparing her food (adaptation) in response to seeing Kate struggling to prepare a meal and Kate describes this intervention as a relief. The local church she attends provides lunch following the Sunday service, but she does not attend as access to the toilet is problematic (threat). Kate's story illustrates how her social network plays a positive role in preventing a bad outcome but structural factors such as suitable toilet facilities limit Kate's independence and enjoyment of socialising beyond her home, compounded by the embodied nature of her mobility and physical health issues.

Bridget explained that she was no longer able to get out of her home due to advanced mobility problems and visual impairment (threats). She described how she relies on her paid carer to shop for her (adaptation), which could appear to address the threat caused by poor mobility; however, Bridget experiences considerable loss of agency, further exacerbated by no longer being able to choose where her food is purchased, thereby displacing the meaning of the food purchased. For Bridget, this is not a successful adaptation, though it could be considered by some to be a trivial issue, that has had a negative impact on her wellbeing:

Well it isn't where I prefer, it's where she finds it more convenient … it's the carer's choice.

Bridget's case illustrates how the relationship between threats and coping capacity is more complex than the linear model presented by Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti (Reference Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti2006), in that an intervention aiming to support coping capacity (through employing a carer), could carry its own threats. For example, Bridget is restricted by what her paid carer has the skills and time to prepare. Her paid carer visits for 30 minutes to help her reheat her frozen meal, but uses timings to fit her work schedule rather than the specified time on the meal packaging, raising food-safety concerns (threat).

Around a third of participants lived with diabetes, which they said affected their food practices through changing the foods they chose to eat or avoid. Patrick described receiving conflicting advice (threat) from the different doctors he saw after diagnosis – but he felt ‘the main thing was that I had to get the weight off’. He and his partner said that they do not buy any special ‘diabetic’ foods but have adapted the foods they eat and their portion sizes. Maya explained how diabetes runs in her family (exposure, threat) and how she had adapted by avoiding some foods: ‘you just have to moderate yourself … I can eat chocolate, but you eat it to moderation’.

Health-related threats had a direct impact on food security, challenging participants to adapt accordingly. This affected many aspects of practices; material objects were now required (e.g. walking aids), there is a need for new knowledge (e.g. how to deal with diabetes-related dietary changes) and changes to meanings were unavoidable (lack of choice relating to adaptations to food purchasing).

Threats to food practices due to loss and bereavement

Exposure to bereavement through loss of a spouse had a major impact on food practices for some households. The emotional response to loss (meaning) is experienced in a visceral and embodied way, affecting the ability to enjoy or even eat food, often for prolonged periods of time. Chris lost his wife six years ago, for example, and explained how he found eating very difficult (threat):

I just carried on cooking, you know, cooking for myself. I was cooking, and the first year I suppose, and I had a bit of a struggle then because preparing food, cooking it, serving it up, and I often just looked at it on the plate and thought, ‘Oh I can't eat that’, and just threw it away. It wasn't because it wasn't cooked nicely, or anything, I just could not, emotionally, sit down and eat a meal.

Other participants, had to develop knowledge and skills they had not previously needed in order to cope with shopping or cooking following bereavement. Some participants explained how, though they had the skills to cook, following the loss of a spouse, they stopped cooking, lost interest in food and often avoided socialising. The meaning of food changed following exposure to bereavement. Mary describes how she found it difficult to cook and eat following the loss of her husband (threat). She had not cooked for six months following his death and now eats microwave meals for one. Her social network had become more important and her daughters came and ate with her, helping her to resolve the threat partially through finding new meaning in her eating practices.

Food shopping practices

Routines and temporal patterns associated with shopping were largely unconscious and people were often unable to articulate how or when these had formed. These routines developed over their life had a significant impact on structures and meanings of household shopping activities and were a well-formed presentation of their habitus (Jenson et al., Reference Jenson, Grønnow and Jespersen2019). People generally shopped on the same day and in the same shops every week, making use of a range of resources and material ‘things’ such as shopping trolleys and bags that formed part of the practice of shopping. Many of the ‘go-along’ tours with participants showed supermarket aisles strewn with obstacles, including people stopping to chat to each other, trolleys and packing crates. These activities and objects were such an embedded part of everyday practice that unless something happened to draw attention to them, they remained unconsidered by many participants.

All households had made some adaptations to their habitus in response to a range of past and ongoing events (threats), however, not all these adaptations were considered to be positive by participants and not all threats could be addressed, as described below.

Transportation and shopping practices

Availability of and access to transport was a major influence on the selection of shopping venues. Participants accessed food stores by walking, bus, taxi and driving a car, or a mix of these. Those who walked to shops often had to navigate threats due to pavements blocked with cars or covered with wet slippery leaves and other hazards.

Those households with access to a car were mainly unrestricted regarding where they shopped. One participant, Renee, however, describes how poor access to disabled parking spaces near to her preferred store was a major factor that led her to change shopping destination once her husband Alfred needed to use a walking frame. Renee explained that prior to his illness, shopping choices were heavily influenced by the couple's exposure to ecological concerns (meanings), but they now have to suspend these ethical beliefs, developed over a lifetime, due to the limitations imposed by structural factors. These enforced changes trouble Renee deeply, and her food choices are now less acceptable to her. Making changes has impacted on the meanings of their practices, creating tension in their moral and social belief structure.

Roland explained how he now used a mixture of transport methods following the onset of health issues, explaining the adaptations he had made and how this influenced his choice of shop:

I go by bus but I always come home by taxi because of my heart problem … I go down to the town where, when I can get off the bus I can go straight into my bank which is at the bus stop, down to [supermarket] which has got a taxi rank when I come out.

Another participant, Janey, uses a walking aid with an inbuilt seat, so relies on taxis as she can no longer walk to the bus stop at the end of her road. She does a weekly shop, which she combines with visiting the hairdresser or post office. The walking aid enables Janey to rest as she makes her way around the store. During the ‘go-along’ tour, Janey sits down with an exhausted sigh on a number of occasions.

Roland and Janey had both made adaptations that enabled them to continue to do their own shopping and benefit from the agency and social opportunities this provided them.

Social aspects of food shopping practices

The social element of acquiring food was an important asset for almost all households and, for some, food shopping provided their main opportunity for social interaction. Many described their enjoyment at meeting people they knew as they shopped. These social interactions were captured on video, e.g. Lee and Peter met and chatted to several people they knew as they went around the supermarket. Others were filmed interacting with shop staff and chatting to them. Participants commented how staff in shops could make a big difference to their shopping experience, with some basing their choice of shopping venue on the help available in-store. Alice chose to shop where ‘they're very good at taking it to the taxi for you’.

The video footage also captured less-sociable experiences, when shop assistants and other customers were sometimes seen to deliberately avoid engaging in a shared greeting, not talking to the participant at the till and avoiding all eye contact.

Several households had computers and tablets and exhibited technological competency, but none ordered food online. Some had considered this and said they may use the service in the future if they were physically unable to get to the shops. Loss of the sociable aspect and exercise opportunities associated with shopping were reasons given for avoiding online food shopping. James said, ‘and it's just anti-social for a start, you're not meeting anybody and you're not getting any exercise’.

Food-based community assets

People ate in several settings outside the home, including restaurants, supermarket and other cafes, lunch clubs, as well as the homes of friends and family members. As well as providing food, lunch groups and coffee mornings provided meeting spaces protecting against the threat from feelings of social isolation and loneliness. Established social networks acted as safety nets when households were unable to shop for food. Grant told us how his sister had occasionally organised food deliveries when he was ill, and Paul described how his former neighbour's wife shopped for heavier items for him. Many participants described how they contributed to social networks and local communities by providing child care, gifting food, undertaking charity work and sharing knowledge. Networks were important for sharing knowledge about services.

Chris explained how he and his wife had begun to attend a lunch group following his diagnosis of a life-limiting illness. His motivation was to establish new social networks as a form of support for his wife, in preparation for when he died. However, in reality, as she pre-deceased him, he was able to use these networks (adaptation).

A number of commercial, statutory and third-sector resources contributed to household coping capacity through enabling food to be brought into the home. These included meals-on-wheels services, home-delivered frozen ready-meals, assistance with shopping as well as support with food preparation from formal carers. A number described the meals-on-wheels service as a ‘life saver’ that supported them to stay in their own homes and remain independent. Grant, who lives alone, has experienced life-long mental health issues (threat) and lacks cooking skills (exposure). He relies on the meals-on-wheels service to provide his main hot meal every day (adaptation). He also obtains milk from the milkman who delivers to his doorstep, and with whom he has struck up a friendship, and benefits from the brief social encounter with the person delivering the meals-on-wheels. Janey tells how the meals-on-wheel service ‘makes me independent, which is what I wanted to be’, thereby protecting her from food insecurity. Gerald has limited cooking skills (exposure) and buys frozen meals that have been delivered to his home weekly (adaptation), following the death of his wife. He likes the convenience as you ‘just shove it in the microwave and four minutes later it's ready’. The meals he buys are placed in the freezer by a delivery-man.

I could see that it was the easiest thing for me to be able to use the microwave and just shove it in there as opposed to trying to work out the regulo on the gas and all that. (Gerald)

For some, growing food on allotments or in their garden was an important asset, as well as contributing food to the household (and beyond it, as people shared surplus food with family and friends). Growing food enhanced wellbeing through connecting with nature, enjoying fresh air and exercise, and mastery of the skills needed, as well as saving money. Linda, for example, grows a wide range of produce, which she shares with her grown-up children and friends, and describes her allotment as keeping her fit and active: ‘when I've got allotment [sic] I feel happy, when I can grow my vegetables, I know I'm still on my mark’. Patrick enjoys mentoring people new to allotment growing and passing on his skills.

In summary, a number of community-based assets contributed to the coping capacity of older people, thus protecting them from threats to food insecurity. Importantly, older people did not just draw from these assets, but contributed to them, and this added to the meanings attributed to and from community-based assets. These findings form an empirical foundation for the model and policy recommendations presented below, as they build on data that detail some of the determinants of vulnerability in later life.

Discussion

This study has revealed a number of food-related social practices that influence the food security of older households. We have outlined the protective assets people draw on to make adaptations that protect them from vulnerability. Changes to physical and mental health, as well as structural and environmental factors such as supermarket design, moved people towards food insecurity and a more vulnerable state. Importantly, the study revealed how threats that are seemingly trivial to an outside viewer could accumulate to move older households towards a more vulnerable state. In addition, the food system itself contributes to these vulnerabilities.

Food practices throughout life are socially constructed, structural, situational, temporal, embodied and relational (Virokannas et al., Reference Virokannas, Liuski and Kuronen2020). Food practices of older households are not fixed, with threats both major and trivial demanding regular adaptations (Vesnaver, Reference Vesnaver, Keller, Payette and Shatenstein2012; Nyberg et al., Reference Nyberg, Olsson, Örtman, Pajalic, Andersson, Blücher, Lindborg, Wendin and Westergren2018). Drawing on coping capacities allows people to respond to threats and make adaptations that move them away from vulnerability. Our findings demonstrate that vulnerability in relation to food security is structured by the habitus but vulnerability is a fluid state, and not uni-directional.

Cumulative trivia and vulnerability

A defining feature of cumulative trivia is their everyday nature. Factors that are individually minor become increasingly difficult to deal with as they accumulate. As Newall et al. (2006: 331–332) argue, the concept needs to be taken seriously as it ‘legitimises older people's experiences of minor difficulties’ and, if unaddressed, ‘the continual investment of precious energy and the repeated feelings of upset, frustration or fear when tasks become unmanageable may become overwhelming’. In this study we saw, and older people described, numerous examples of the types of trivia they experience every day as they interact with the food system. Supermarkets themselves often had a major and detrimental effect on the food practices of people as they aged. The social spaces of supermarkets are structured in such a way that the experience of shopping can become ‘too difficult’ due to lack of resting spaces or making people feel rushed as they pack and pay for food. Participants described encounters with inadequate toilet facilities that challenged or prevented them from undertaking food shopping and eating out. Ford et al. (Reference Ford, Trott and Simms2016) used the concept of daily hassles to explore older people's engagement with food packaging. They found physical struggles with packaging on goods led older people to experience vulnerability, but they also experienced anticipated vulnerability. This meant those cognisant of their own ageing responded in a negative way, leading to feelings of helplessness.

As many of the threats older people face are trivial but cumulative, we argue that interventions to reduce this accumulation could also be incremental, thus having a positive cumulative impact. We argue that those seeking to make a difference to the food security of older people could learn from the successful application of the ‘aggregation of marginal gains’ theory used in elite cycling and other cutting-edge sports such as Formula One (Slater, Reference Slater2012). Nierenberg et al. (Reference Nierenberg, Hearing, Sande Mathias, Young and Sylvia2015) argue that this approach, which seeks to make ‘small and doable improvements across a broad range of areas’ could help people with mental health issues, for example. Other researchers have found that engaging in shopping trips reduces feelings of isolation, which were especially important for those living alone, and our study noted the relational value of brief social encounters and friendly conversations within shopping venues. Kim and Kim (Reference Kim and Kim2005) noted that the needs of older consumers are often unmet by retailers. The retail environment plays a key role in reducing social isolation (Forman and Sriram, Reference Forman and Sriram1991). A UK report (Euan's Guide, 2018) on accessibility for disabled people found that 53 per cent perceive shops as difficult to access. However, 72 per cent of disabled people were more likely to visit somewhere new if they felt welcomed by staff or the venue appeared to care about accessibility. A recent toilet survey (Euan's Guide, 2017) found that 84 per cent of people with disabilities avoided going somewhere due to lack of accessible toilets, with 44 per cent of supermarket toilets rated as poor. Other researchers found that disabled people planned activities such as shopping, work and socialising around access to toilets (Kitchin and Law, Reference Kitchin and Law2001). While addressing these ‘trivia’ could appear insignificant to an able-bodied or younger person, these disproportionately affect older households, but the effect extends beyond the individual, having far-reaching economic consequences for society. Brancati and Sinclair (Reference Brancati and Sinclair2016) reported that mobility issues were associated with a 13 per cent drop in spending on eating out, with loss to the UK retail economy alone from older shoppers estimated at £3.8 billion. The over fifties currently account for 47 per cent of all UK consumer spending, at £320 billion per year (Centre for Future Studies, 2017), so interventions to support older people to shop for their food also make economic sense.

A new model to guide interventions that protect older households from vulnerability to food insecurity

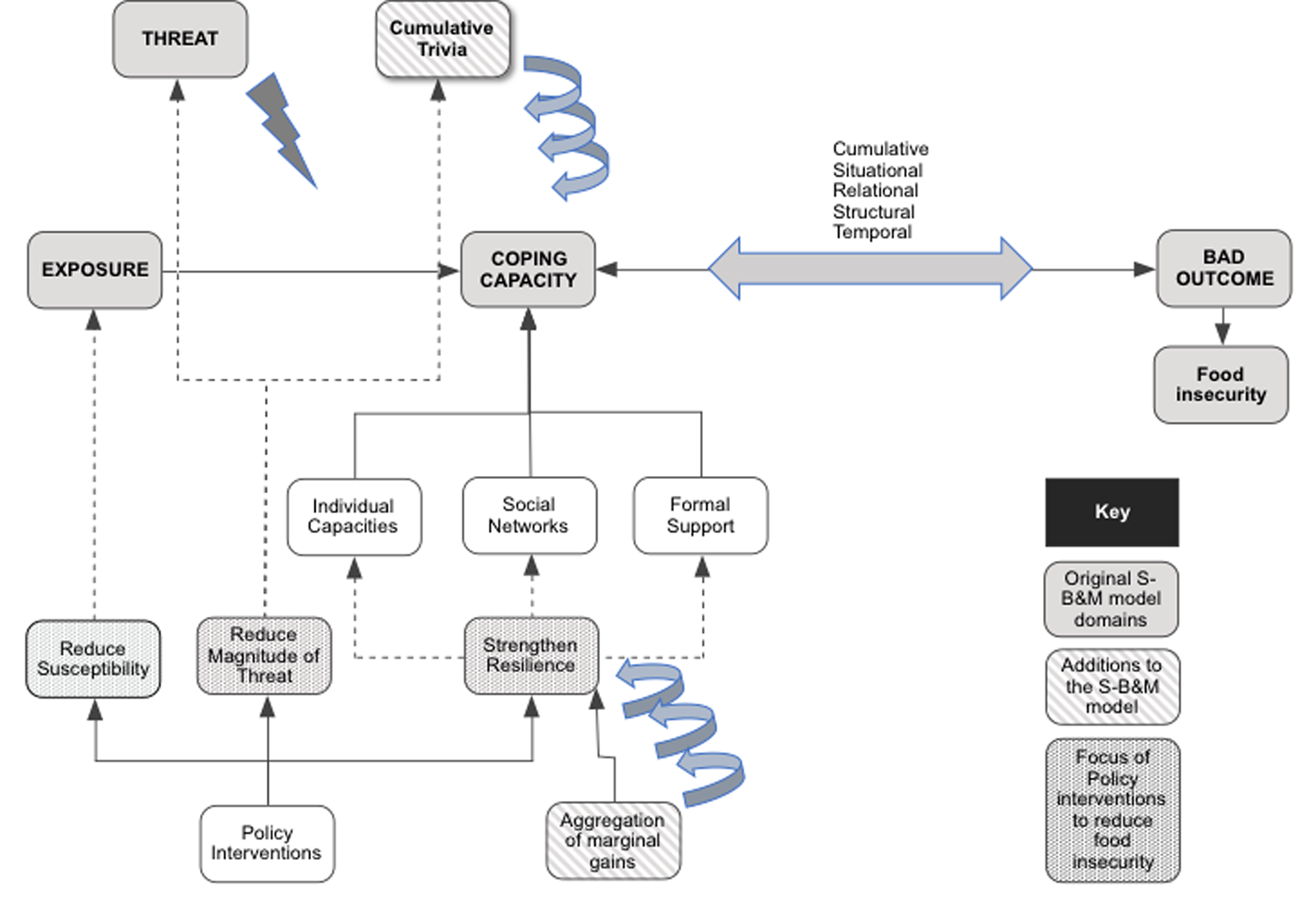

As a vulnerable state is socially constructed, we argue this can be addressed and reversed. We saw many examples of older households drawing on a range of coping capacities to help achieve or restore food security. We have, therefore, adapted the Schröder-Butterfill (Reference Schröder-Butterfill2012) model further (Figure 2) as a useful guide for policy makers and others concerned with reducing the vulnerability of this population group. The bi-directional arrow indicates the possibility of reversing vulnerability. We have added the concept of cumulative trivia to show how these build and function as threats; and its opposite, the aggregation of marginal gains, that can build coping capacity. These modifications ensure the model represents older people's everyday experience of vulnerability in relation to food insecurity, showing how multiple elements interact. This model will be of use to policy makers and others seeking to address household food insecurity as it shows the points where interventions can be made to reduce vulnerability. Firstly, intervention can be made before a threat happens. For example, ensuring that old-age pensions keep pace with the cost of living and food price increases means that people can afford to buy nutritious food (Gabriel and Bowling, Reference Gabriel and Bowling2004). Secondly, interventions could focus on decreasing the magnitude of a threat. For major threats, such as exposure to bereavement, our data showed the crucial role social networks play as assets in supporting food security for those experiencing this major life transition. Transportation-related threats can lead to ‘shrinking of activity spaces’ (Ahern and Hine, Reference Ahern and Hine2012). Those in rural areas and the oldest old have been found to be the most affected by poor access to public transport (Shergold and Parkhurst, Reference Shergold and Parkhurst2012). The transition from driving a car to using public transport means that older people are particularly reliant on the availability of effective public transport networks. Thirdly, vulnerability can be delayed by increasing the coping capacity of the individual through strengthening individual capacities, social networks and formal support. Our study indicates the important role played by social networks, with family, friends and neighbours supporting food security (Gustafsson and Sidenvall, Reference Gustafsson and Sidenvall2001). We saw how lunch clubs and coffee mornings played an important social role for many participants (who both contributed to and drew from these) (Fjellström et al., Reference Fjellström, Sidenvall, Nydahl, Frewer, Risvik and Schifferstein2001; Dwyer and Hardill, Reference Dwyer and Hardill2011; Saeed et al., Reference Saeed, Fisher, Mitchell-Smith and Brown2020); and these need to be preserved and developed (Holt-Lunstad et al., Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith and Layton2010). Formal support systems play a major role in supporting older households that were nearer to a state of vulnerability, i.e. those who struggled to or could not get out of their home. For these households, services such as meals-on-wheels and specialist meal provision delivered to their homes, alongside retail suppliers such as milk delivery, were critical (Zhu and An, Reference Zhu and An2013; Walton et al., Reference Walton, do Rosario, Pettingill, Cassimatis and Charlton2019). The area where this research was undertaken has a thriving meals-on-wheels service, but this study raises concerns for older people living in areas where this service no longer exists due to austerity policies (National Association of Care Catering, 2018). There is currently no statutory duty on local authorities to provide meals-on-wheels or food services, and this should be challenged as lack of such services presents a major threat to food security. Many lunch clubs across the UK have also closed or are under threat due to declining attendance (Saeed et al., Reference Saeed, Fisher, Mitchell-Smith and Brown2020), but we do not know how these closures impact on the food security of the older population. Saeed et al. (Reference Saeed, Fisher, Mitchell-Smith and Brown2020) make a number of recommendations to support older people to use lunch clubs, such as thinking about how to advertise these, avoiding stigmatising images and language, offering activities as well as food (this was particularly important for men), and supporting people to take the first step through a personal invitation or attending a group with someone else.

Figure 2. A model illustrating the complexity of household vulnerability in relation to food security and the dynamic nature of the concept.

Note: This model builds on the Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti (Reference Schröder-Butterfill and Marianti2006) and Schröder-Butterfill (Reference Schröder-Butterfill2012) vulnerability model, incorporating the concepts of ‘cumulative trivia’ and ‘marginal gains’.

We concur with recommendations from Kim and Kim (Reference Kim and Kim2005) regarding how retailers could support older consumers better to build on the social meaning of shopping, including emphasising a relaxing and comfortable experience where social encounters are encouraged, offering events tailored to older consumers, sales people offering a personal service, targeting offers and providing eating places that are pleasant spaces to socialise (Wills and Dickinson, Reference Wills and Dickinson2020). Other interventions such as ‘slow shopping’ (www.slowshopping.org.uk), with staff training and supportive environmental modifications, such as providing additional seating, can be beneficial for older shoppers.

Using ethnographic methods enabled us to capture everyday interactions with food systems, moving beyond a description of ‘it's just what we do’, to reveal their complexity, richness and entangled nature (Wills et al., Reference Wills, Dickinson, Meah and Short2016), and enabled us to make the familiar strange (Mannay, Reference Mannay2016). Virokannas et al. (Reference Virokannas, Liuski and Kuronen2020) noted the lack of effort to analyse theoretically or use the concept of vulnerability in an innovative way and this study addresses this. Variation in data was achieved through including women and men from a range of living contexts and across four decades of older age. The study was undertaken in one geographical area in the East of England, so similar studies in other areas are recommended.

There is a need for more research into what happens to food security in places where services such as meals-on-wheels are non-existent to explore the impact on older people, formal care and the associated health economic costs. Further research should focus on periods of transition, e.g. retirement, widowhood or divorce, transitioning to informal and formal care, and those who may be particularly vulnerable, e.g. those on low incomes, single and childless, and living with complex long-term conditions and dementia.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Economic and Social Research Council for funding the study. We are particularly grateful to our participants for generously giving their time and enabling us to spend time with them. Thank you to members of our external Advisory Group for their advice and support throughout the study. We are grateful to the CRIPACC Public Involvement in Research Group, who checked the study documentation. Particular thanks are due to John Willmott who took part in testing the methods with us, and to John and Alex Mendoza for their input into the study Advisory Group.

Author contributions

W Wills, A Dickinson, F Ikioda, A Kapetanaki and S Halliday contributed to the design and planning of the study, F Ikioda, A Godfrey-Smythe, W Wills and A Dickinson undertook data collection. A Dickinson, F Ikioda and A Godfrey-Smythe coded data. A Dickinson reviewed the full data-set and drafted the paper. All authors took part in data analysis and interpretation of data, commented upon the draft and revisions and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council and Food Standards Agency (ES/M00306X/1). The funding body played no part in the design, execution, analysis or interpretation of data, or in this paper. Data supporting this publication can be accessed at http://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/853050.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was gained from the University of Hertfordshire's Ethics Committee with delegated authority (reference cHSK/SF/UH/00073). All study documentation was reviewed by the University of Hertfordshire's Public Involvement in Research group. Informed consent was treated as a process, as opposed to a one-off event, and was re-negotiated throughout the study (Dewing, Reference Dewing2007). None of the names given in this paper are the real names of participants.