Introduction

Dementia is a progressive neurodegenerative condition characterized by symptoms that can lead to a variety of changes in cognitive and behavioural function (Alzheimer Society of Canada 2024; Public Health Agency of Canada 2022a; Ward and Sandberg Reference Ward and Sandberg2023). Symptoms of dementia are unique to each individual and can greatly impact personal and social identities and relationships (Alzheimer Society of Canada 2024). Dementia impacts approximately 55 million people globally and this number is expected to rise to 139 million people by 2050 (CanAge 2022; World Health Organization 2023). In Canada, rates of dementia are expected to increase over the next three decades, with more than 6 million people expected to develop the condition (Alzheimer Society of Canada 2024; Public Health Agency of Canada 2022b). Globally, dementia is a major cause of disability and dependency among older individuals and is the seventh leading cause of death (World Health Organization 2023).

Research suggests that rates of dementia among Indigenous Peoples are increasing faster than in non-Indigenous Peoples (Walker et al. Reference Walker, O’Connell, Pitawanakwat, Blind, Warry, Lemieux, Patterson, Allaby, Valvasori, Zhao and Jacklin2021). In Canada, First Nations people have a prevalence of dementia of 7.5 per 1,000, compared to non-First Nations people’s prevalence rate of 5.6 per 1,000 (Jacklin et al. Reference Jacklin, Walker and Shawande2013). Similarly, rates of dementia are higher in American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) populations when compared to non-Indigenous populations in the USA (Mayeda et al. Reference Mayeda, Glymour, Quesenberry and Whitmer2016). Increased dementia prevalence and earlier age of onset are also observed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in Australia and with Māori and Pacific Islander populations in New Zealand (Jacklin and Chiovitte Reference Jacklin, Chiovitte, Innes, Morgan and Farmer2020; Li et al. Reference Li, Guthridge, Eswara Aratchige, Lowe, Wang, Zhao and Krause2014; Ma’u et al. Reference Ma’u, Cullum, Yates, Te Ao, Cheung, Murholt, Dudley, Krishnamurthi and Kerse2021; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Flicker, Lautenschlager, Almeida, Atkinson, Dwyer and Logiudice2008).

Colonization and ongoing colonial practices continue to harm Indigenous people, contributing to the perpetuation of health inequities, compounding the effects of systemic racism and increasing the risk of developing dementia (Alzheimer Society of Canada 2024; MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Barnes and Middleton2015). Researchers suggest that colonization has had detrimental effects both historically and currently because of ethnic and cultural genocide (Evans-Campbell Reference Evans-Campbell2008; Paradies Reference Paradies2016; Priest et al. Reference Priest, Paradies, Stewart and Luke2011). As Smallwood et al. (Reference Smallwood, Woods, Power and Usher2021) describe, colonization has had a profound impact on Indigenous populations on many levels including physical, mental, social, spiritual, economic and cultural. Moreover, Henderson et al. (Reference Henderson, Furlano, Claringbold, Cornect-Benoit, Ly, Walker, Zaretsky and Roach2024) state that the determinants of health that play a crucial role in the health of Indigenous peoples include the history of colonization, systemic racism, cultural perspectives and practices, and access to health care.

In the health-care system, a lack of understanding regarding the impacts of colonization on Indigenous Peoples contributes to unsafe dementia care that ignores and undermines Indigenous ways of knowing (i.e. epistemology and ontology) (Racine et al. Reference Racine, Johnson and Fowler-Kerry2021) which include collective, relational and reciprocal approaches to understanding the world. Moreover, the dismissal of culture in the health-care system greatly impacts healthy ageing and conceptions of dementia from an Indigenous worldview (Quigley et al. Reference Quigley, Russell, Larkins, Taylor, Sagigi, Strivens and Redman-Maclaren2022). The understanding of dementia in a Western worldview can be different from that in an Indigenous worldview. For instance, Cornect-Benoit et al. (Reference Cornect-Benoit, Pitawanakwat, Walker, Manitowabi and Jacklin2020) found perceptions of dementia among First Nations people can be that it is not a problem or a medical concern, but rather a part of life and coming full circle. Similarly, Lanting et al. (Reference Lanting, Crossley, Morgan and Cammer2011) found that dementia is understood as a normal part of the ageing process, while highlighting the importance of culture in assessment and the health-care system. This difference between worldviews can result in dementia care that is not culturally safe for Indigenous populations.

Developed in New Zealand in the 1980s, the theory and application of cultural safety was developed in response to the Māori people’s dissatisfaction with nursing care (National Aboriginal Health Organization 2008). According to the National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO), cultural safety means ‘that the educator/practitioner/professional, whether Indigenous or not, can communicate competently with a patient in that patient’s social, political, linguistic, economic, and spiritual realm’ (National Aboriginal Health Organization 2008, p. 4). Moreover, cultural safety recognizes the power imbalances in the health-care system that result in Indigenous peoples receiving care based on colonization, system racism and white supremacy (Chakanyuka et al., Reference Chakanyuka, Bacsu, DesRoches, Dame, Carrier, Symenuk, O’Connell ME, Crowshoe, Walker and Bourque Bearskin2022). Therefore, culturally unsafe care refers to ‘any actions that diminish, demean or disempower the cultural identity and well-being of an individual’ (Nursing Council of New Zealand [2005] 2011, p. 7; see also Brascoupé and Waters Reference Brascoupé and Waters2009; Cooney Reference Cooney1994). When compared to cultural sensitivity, cultural competence and cultural awareness, cultural safety goes deeper to understand the power imbalances and the roles of colonization and colonial relationships in a health-care setting (Hole et al. Reference Hole, Evans, Berg, Bottorff, Dingwall, Alexis, Nyberg and Smith2015; National Aboriginal Health Organization 2008). The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) recognizes the importance of addressing colonial legacies related to health, including ‘the right to access, without any discrimination, to all social and health services’ and ‘an equal right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health’ (United Nations General Assembly 2007, p. 18).

Nonpharmacological dementia interventions are focused on supporting independence and participation in daily life activities, with emphasis on enhancing quality of life in personal and contextually relevant ways (Bourgeois and Hickey Reference Bourgeois and Hickey2018). Despite increases in recorded rates of dementia diagnoses for Indigenous peoples (Jacklin et al. Reference Jacklin, Walker and Shawande2013), culturally safe dementia care interventions are not available or not routinely implemented (Chakanyuka et al. Reference Chakanyuka, Bacsu, DesRoches, Dame, Carrier, Symenuk, O’Connell ME, Crowshoe, Walker and Bourque Bearskin2022; Jacklin and Chiovitte Reference Jacklin, Chiovitte, Innes, Morgan and Farmer2020). Culturally safe interventions would include respecting and understanding the inherent significance of the beliefs and values of Indigenous people. Retaining connection to cultural identity, knowledge and traditions is a protective factor that promotes health and wellbeing for many Indigenous people (Crowshoe et al. Reference Crowshoe, Henderson, Jacklin, Calam, Walker and Green2019; Hulko et al. Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010). Indigenous conceptualizations of health and health care, such as nature-based approaches for improving mental health and older adult services designed by Indigenous people, are effective, but they are severely under-utilized within health systems (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Harfield, Davy, Baker, Kite, Aitken, Morey, Braunack-Mayer and Brown2021; Fatima et al. Reference Fatima, Liu, Cleary, Dean, Smith, King and Solomon2023; Yashadhana et al. Reference Yashadhana, Howie, Veber, Cullen, Withall, Lewis, McCausland, Macniven and Andersen2022). Therefore, it is important to increase awareness and implementation of culturally safe protocols in health care, including dementia care, to help decrease barriers and increase health equity for Indigenous populations (Brascoupé and Waters Reference Brascoupé and Waters2009; Crowshoe et al. Reference Crowshoe, Henderson, Jacklin, Calam, Walker and Green2019; Ramsden Reference Ramsden1993).

To address the growing health inequities caused by increasing rates of dementia in international Indigenous populations, the purpose of this scoping review was to characterize and describe current models and outcomes of dementia care interventions designed specifically for Indigenous people living with dementia.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review from May to September 2023 to evaluate and summarize the existing literature available on culturally safe dementia care interventions for Indigenous populations. The scoping review followed the methods outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005). We searched OVID (Medline, PsycINFO, Embase, Healthstar), Informit Indigenous Collection, JBI EBP, Scopus/Elsevier and PubMed. Our team consisted of Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers and students, and a health sciences librarian.Footnote 1

Search strategy

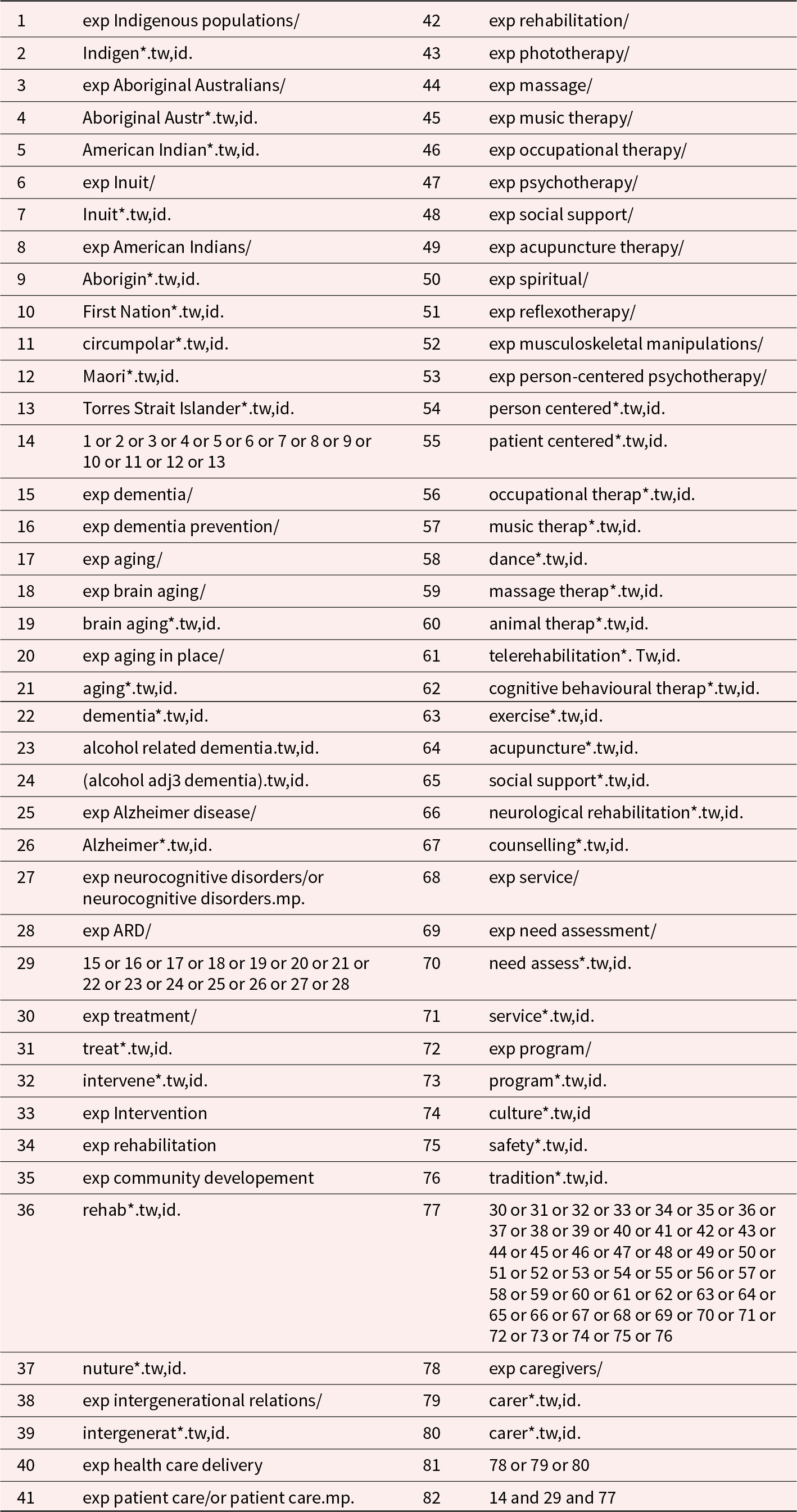

The search strategy was designed to identify culturally safe, Indigenous-specific dementia interventions. Specifically, inclusion criteria for the scoping review included the following: must be specific to an Indigenous population; must focus on dementia; must be a dementia intervention; and must focus on the person with dementia rather than a care-giver or health-care worker. The detailed search strategy was developed in partnership with a health research librarian to design a rigorous search that was as inclusive as possible. Key search terms included those related to Indigenous identities, dementia and interventions. The detailed search strategy is available in Table 1.

Table 1. Detailed search strategy

Source selection

Sources needed to meet the following criteria for inclusion: must be published in English; must relate to interventions designed specifically for Indigenous persons living with dementia; and must provide evaluative outcomes of the intervention. Studies that were designed for care partners and/or health-care professionals only were excluded. The search results were managed through the online platform COVIDENCE.

Data extraction and analysis

Two reviewers (MO and ML) used a common data extraction form in Excel. The data extraction form included article information such as title, author, document type, publication year, location (country/region), study design, study sample, start/end year, age range, gender, geographic area and population. Additional fields were structured so that included manuscripts could be classified as explicitly having or not having an intervention component for inclusion/exclusion as well as the name of the intervention, the content, the design, the principles, practices, successes, culture-based outcomes, community engagement and any future directions. Intervention design and structure had to include details of the mode (in person/group/with a care-giver, self-guided), the specific content included, whether they were successful or not and why, and any limitations. Any articles that were included for full-text review were independently reviewed and evaluated by MO and ML. Any disagreements were discussed between the reviewers and resolved with assistance from the project team and the senior author (PR).

Results

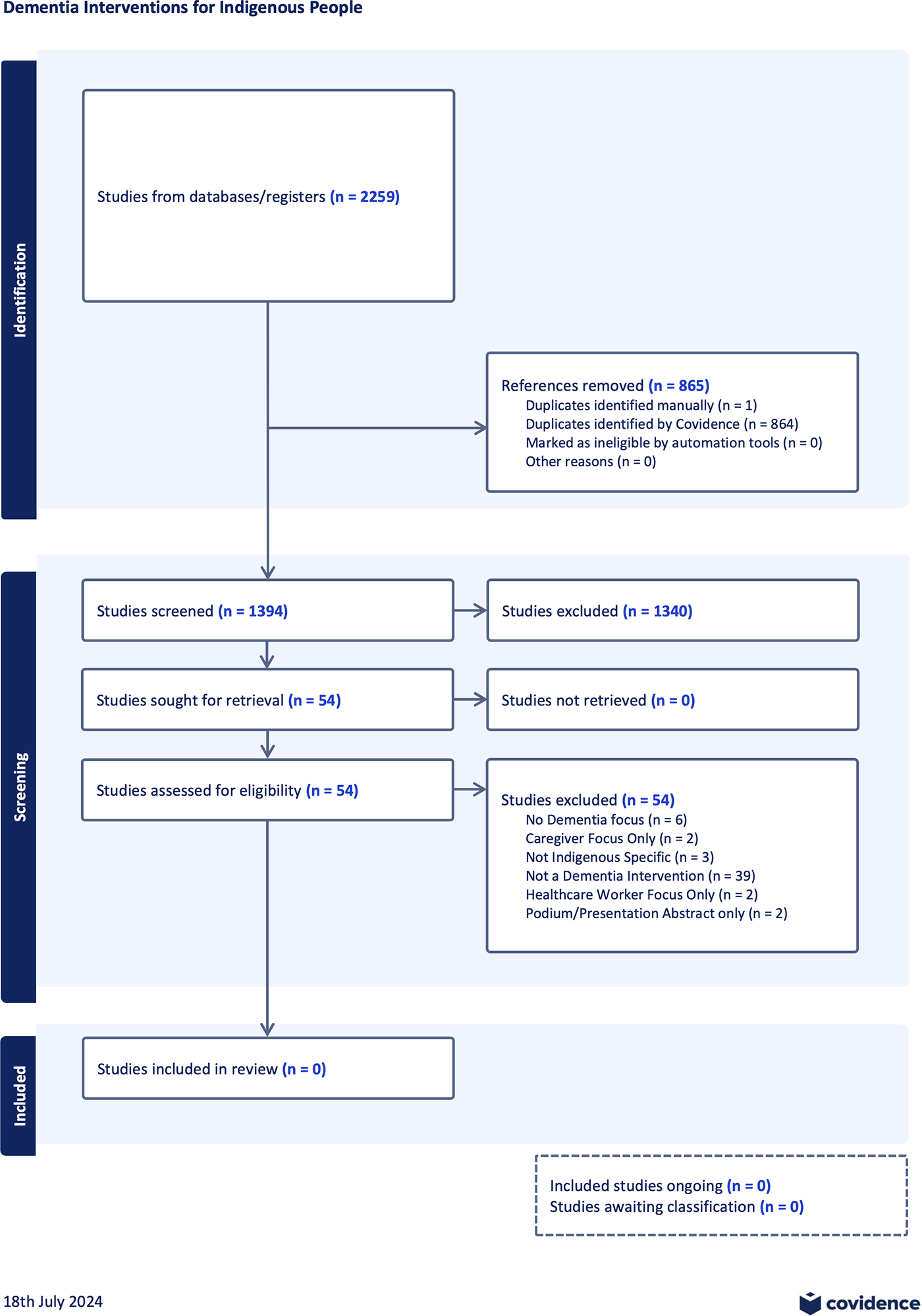

In total, 2,259 articles were identified in the initial search. Sources were imported to COVIDENCE where 865 duplicates were removed, leaving 1,394 studies for title and abstract screening (Figure 1). A further 1,340 studies were excluded following title and abstract screening because they were not specific to Indigenous people or dementia, or because they focused solely on care-givers or health-care workers. The remaining 54 articles were screened for full text eligibility, where all studies were excluded because they were not a dementia intervention (n = 39), they were not dementia-specific (n = 6), they were focused on health-care workers or care partners only (n = 4), they were not Indigenous-specific (n = 3) or they were conference abstracts with no appropriate data available (n = 2).

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram.

Discussion

The objective of this scoping review was to determine what models and outcomes existed for culturally safe dementia care interventions for Indigenous populations. The results yielded no studies that fit our inclusion criteria. A scoping review with no eligible literature is referred to as an empty review (Gray Reference Gray2021; Lang et al. Reference Lang, Edwards and Fleiszer2007). Empty reviews are crucial in highlighting important gaps in knowledge, as well as identifying where priorities should be focused (Gray Reference Gray2021; Lang et al. Reference Lang, Edwards and Fleiszer2007). In this case, there is an urgent need to prioritize the development, implementation and evaluation of culturally safe, Indigenous-specific dementia interventions in collaboration with Indigenous peoples.

The literature found in our scoping review focused on dementia from the perspective of a care partner or health-care worker, rather than from that of a person living with dementia. Historically, people living with dementia have often been excluded from participation in research (Ward and Sandberg Reference Ward and Sandberg2023); however, there is an increasing imperative to involve people with dementia in research and to include their perspectives and experiences (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Jordan, Hunter, Cooney and Casey2015). Excluding people with lived experience from the research process is unethical and perpetuates stereotypes of what people think dementia is or is not. In fact, Chapman (Reference Chapman2002) argues that people with dementia must be included in the research process for researchers to develop a complete understanding of the lived experience while addressing power imbalances that contribute to stigma. Furthermore, for Indigenous people engaged in research, the process may be grounded in ceremony, and any research methodology ‘needs to incorporate their cosmology, worldview, epistemology, and ethical beliefs’ (Wilson Reference Wilson2008, p. 15). By including Indigenous people living with dementia in the research process, researchers can support the inherent right to self-determination, which is one of the most important determinants of health and contributes to positive health outcomes (Auger et al. Reference Auger, Howell and Gomes2016; Oster et al. Reference Oster, Grier, Lightning, Mayan and Toth2014). This is a critical consideration for future research in this area.

Our search of the literature found that cultural safety in dementia care focused on policy recommendations and descriptions of how an intervention could be implemented. Although policy recommendations and ideas around intervention are important, it is crucial that these lead to practical applications and real-life interventions. Furthermore, the literature discussed the need to create diagnostic tools, adapt diagnostic procedures to local populations and create culturally safe tools for consideration. Walker et al. (Reference Walker, O’Connell, Pitawanakwat, Blind, Warry, Lemieux, Patterson, Allaby, Valvasori, Zhao and Jacklin2021) recently adapted an Indigenous-specific cognitive assessment tool that integrates culturally safe, trauma-informed approaches to dementia care. Assessment is an important piece of care planning, but without culturally safe supports and services in practice, Indigenous people with dementia will continue to be underserved. Future research should focus on ensuring that the impacts of colonization are understood by health-care systems and translated into policies and health services that place the utmost importance on Indigenous ways of knowing (Quigley et al. Reference Quigley, Russell, Larkins, Taylor, Sagigi, Strivens and Redman-Maclaren2022; Racine et al. Reference Racine, Johnson and Fowler-Kerry2021).

Owing to the growing prevalence and incidence of dementia among Indigenous populations, there is a strong impetus to develop, pilot, and evaluate culturally safe dementia interventions to decrease harm and improve the quality of life for Indigenous people living with dementia. Culturally safe dementia interventions must be co-designed and co-developed with Indigenous populations and designed in ethical ways by collaborating with Indigenous peoples at the very beginning of a research study (Wilson Reference Wilson2008). Research with Indigenous populations must adhere to the principles of the UNDRIP (United Nations General Assembly 2007) and honour the research principles relevant to specific cultures or nations, including nation-led ethics approval processes, if applicable (First Nations Information Governance Centre 2014; Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami 2018; National Aboriginal Health Organization 2010). Additionally, it will be important to assess how non-Indigenous people and groups conducting research authentically engage and collaborate with Indigenous people to ensure that interventions are meaningful and reflect community priorities (Yashadhana et al. Reference Yashadhana, Howie, Veber, Cullen, Withall, Lewis, McCausland, Macniven and Andersen2022).

The paucity of research on culturally safe, Indigenous-specific dementia care interventions speaks to an appalling lack of action towards recognizing the inherent rights of Indigenous people to self-determination and sovereignty. Internationally, the UNDRIP recognizes ‘the urgent need to respect and promote the inherent rights of Indigenous people’ and affirms ‘the fundamental importance of the right to self-determination of all peoples’ to determine and freely pursue ‘social and cultural development’ (United Nations General Assembly 2007, p. 3). The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s calls to action include calls directly related to health (Calls 18–24) which include: closing health outcome gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities (Call 19, p. 161); recognizing, respecting and addressing the distinct health needs of Indigenous populations (Call 20, pp. 162–163); and recognizing the value of Indigenous healing practices to treat patients in collaboration with healers and Elders (Call 22, p. 163) (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). As of December 2023, only 13 of the 94 calls to action have been addressed (Jewell and Mosby Reference Jewell and Mosby2023). Alarmingly, none of the completed calls to action relate to the health of Indigenous peoples.

Strengths and limitations

There are many strengths to this study, including a team led by an Indigenous scholar with a long history of working in dementia research; a rigorous search strategy; and multiple reviewers on inclusion and exclusion decisions. However, it is possible that dementia interventions specific to Indigenous populations exist but have not been reported in the published literature. An additional limitation is that our search was restricted to include only articles published in English. Future work should expand these parameters with recruitment to research and project teams being mindful of these limitations. Finally, we did not publish a review protocol prior to the review.

Conclusion

The results of this empty review should serve as a wake-up call to address health-care inequities for Indigenous people living with dementia. A lack of research on culturally safe, Indigenous-specific dementia care means that Indigenous people living with dementia will continue to be unsafe and underserved in our current health and social care systems. Moreover, without the inclusion of Indigenous people living with dementia in the research process, supports and services will not be cognizant of the ongoing impacts of intergenerational trauma and colonization. Future research should partner with Indigenous people living with dementia to determine a dementia care model that is strength-based and trauma-informed, while also being grounded in Indigenous knowledge systems and experiences.

Financial support

No funding sources to declare.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.