Introduction

The establishment of the first newspaper in Nigeria within the power structure of nineteenth-century imperial rule appears to have had a reverberating and lasting effect on why newspapers are established and on how news media, including newspapers, convene their audiences in postcolonial Nigeria. Iwe Irohin, established in 1859 by Reverend Henry Townsend and other missionaries of the Anglican mission in Abeokuta, ostensibly to promote literacy among the Yoruba people, was part of the technology of British imperialism.Footnote 1 It was at once an apparatus of power and a tool for both evangelism and proselytizing among the mainly indigenous Yoruba population. Although it was a local-language newspaper, its founders did not establish it solely for the promotion of Yoruba language. Iwe Irohin, a mouthpiece of the missionaries, was, more than being a means of disseminating information, education and entertainment, very much a tool for ‘promoting so-called legitimate commerce’ in addition to providing a discursive space in which to air the ideas and comments of the missionaries on political developments in the region (Coker Reference Coker1968: 3–4).

The English-speaking population at this time was too small to sustain an English-language newspaper, and the adoption of Yoruba as an instrument for the transmission of the religious and political messages of the founders of Iwe Irohin was therefore inevitable. The fact that there was a fast-rising literate population among the Yoruba was also an important factor. The decision or choice of which language to use by the mass media, as Oso (Reference Oso and Salawu2006) rightly notes, is not one based on idealism but rather the outcome of the interplay of political and economic forces within a given historical milieu. This would prove to be the case especially within the conflictual structure of colonial administration, and particularly colonial urban centres that brought precolonial social formations, otherwise called ethnic groups, together in one space where they had to compete for scarce socio-economic and political resources. This would give rise to ethnic consciousness (Nnoli Reference Nnoli1978; Osaghae Reference Osaghae1998), thereby leading to the promotion of ‘ethnic’ or identity politics. This point is underlined by Nyamnjoh's (Reference Nyamnjoh2015) warning that the success of democracy and journalism in Africa depends on the recognition that most Africans, like everyone else, reserve their primary allegiance to their home village, ethnic or cultural community and accord only secondary consideration to the state and country as entities in the postcolony. As Nyamnjoh goes on to elaborate: ‘It is in acknowledging and providing for the reality of individuals who straddle different forms of identity and belonging, and who are willing or forced to be both “citizens” and “subjects”, that democracy stands its greatest chance in Africa, and that journalism can best be relevant to Africa and Africans’ (ibid.: 39, emphasis added). Identity politics is therefore at the heart of newspaper culture in Nigeria; it speaks to the means and manner of genre formation in news media and the way in which news media convene their audience.

The Nigerian press is oriented along different socio-political lines, with the location of newspapers, the ethnic identity of their publishers and the main market they court sometimes being pointers to their editorial bent (Uduak Reference Uduak2000; Abati Reference Abati, Oseni and Idowu2000; Salawu Reference Salawu and Oni2008). Adebanwi (Reference Adebanwi2016: 11) observes that fundamental questions of political identity and political community are implicated in the framing of the nexus between the media and political action and between ethnicities and the nation. Apart from the profit motive, therefore, Nigerian newspapers are established as part of the apparatus for the mobilization of meaning (Adebanwi Reference Adebanwi2016: 12–13), and often to champion and defend hegemonic interests in an ethnically polarized polity where politicians very often bankroll or own publishing outfits.

One of the most successful newspapers to achieve the dual goal of ‘ethnic’ and commercial success in recent years – particularly because it is an indigenous-language newspaper – is Alaroye,Footnote 2 a Yoruba-language newspaper whose motto is ‘Iwe Irohin t'o n s'oju omo Yoruba nibi gbogbo’ (‘The newspaper that represents the Yoruba people the world over/everywhere’). Alaroye is now one of the most successful indigenous-language newspapers of all time. The genre-blurring innovations it brings into the Nigerian newspaper market, with its radical blending of Yoruba oral resources in a written medium, a phenomenon already observed with media poetry (Nnodim Reference Nnodim, Ricard and Veit-Wild2005; Barber Reference Barber2007), set it apart from its competitors today and shed light on the ways in which Nigerian newspapers convene their audience and seek relevance in the market place.

Newspapers, contestation and mediation

The approach taken in this article is theoretically eclectic, combining insights from post-structuralist theorization with classical Marxist inflection, Foucauldian discourse analysis and popular culture. As Burton (Reference Burton2010: 13–14) makes clear, discourses involve ways of meaning; they produce meanings about particular subjects and are connected to ideology and representation. For him, discourse analysis involves the analysis of a text through identification of language, with a view to revealing its discourses and commenting on their meanings. Discourse analysis also reveals the ideology behind a text. Methodologically, the approach is both materialist and interpretive. This position accords with the post-structuralist – and specifically the new historicist – formulation of reality or history as simultaneously textualized and represented, contradictory and subjective. Interpretive theorists hold the view that language is constituted by and expressive of the political life from which it derives its essence and logic. This is a viewpoint with roots in Saussurean linguistics, specifically structuralism, but one that has been made more nuanced and refined and has been lent resonance for a modern audience by such post-structuralists as Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault and Mikhail Bakhtin, among others.

In this articulation, the reflectionist view of language and the tendency to draw a natural link between language and objective reality is discountenanced. Rather than viewing language as transcendental and outside history, reality is seen as both created and constituted by language. Thus, based on the notion that the reality on which knowledge is based is socially constructed (Agbaje Reference Agbaje1991: 8), Adebanwi (Reference Adebanwi2016: 32), following Brian Fay (Reference Fay and Gibbons1987), sees interpretive social science as revealing the logic of particular actions and practices with a view to unravelling the motives and intentions of particular actors and the structures and contexts that give life to their activities. Interpretive social science also examines the social scientist's understanding of those actions and practices that form the basis of their investigation. They therefore argue that political life cannot exist as an abstraction or in isolation from the language employed to articulate it. For this category of theorists, therefore, an explanation and/or narration of social and political life is hermeneutical, and, to that extent, is an interpretation.

In addition to its interpretive methodology, this article also draws insight from popular culture and from classical Marxism in its claim that labour mediates the objective nature of the world and that the position people occupy in the labour chain determines their consciousness, a view underlined in the Marxist axiom that it is life that determines consciousness as consciousness does not determine life. The journalistic exertions of Alao Adedayo, the publisher of Alaroye, the motivations behind the different genres that mutated from the original newspaper, and, indeed, their mobilization of meaning and representation of reality have been shaped by the publisher's experience as, first, a media practitioner without professional training whose practice was contingent on and constrained by financial imperatives to a considerable extent. In sum, this article focuses on the performance of hegemony, understood as the construction of consensus by acquiescence, through non-forcible or invisible means. It examines the historical and social contexts of Nigeria under a military dictatorship against the background of the way in which meaning is mobilized for hegemonic purposes through a newspaper's coverage and representation of the Nigerian reality.

The first section traces the history of Alaroye, focusing on the influence of the military in the emergence and stabilization of the newspaper. The second section provides a historical context for Yoruba newspapers, serving as a backdrop to examine Alaroye in the longue durée and its place within a Yoruba newspaper and/or print culture with roots in the nineteenth century. In view of its ascendancy as the leading Yoruba newspaper – which followed in part from its deployment of populist trappings within a culture that placed a premium on literacy, moral rectitude and education as signs of personal enlightenment, aspiration and group edification – Alaroye has passed into the popular consciousness and is now frequently referenced in popular culture. Thus, the third section examines Alaroye as popular art. The fourth and concluding section highlights the genres of Alaroye, its oral written style, its innovative use of language and its role as a political-cum-cultural ‘editor’, evidence of its transformation from a twelve-page, black-and-white ‘magazine’ to a relatively high-definition colour tabloid.

The military factor in the emergence and stabilization of Alaroye

Alaroye was established in 1985 by Alao Adedayo after he lost his job as a broadcaster. Not formally trained as a journalist, his foray into print journalism has been described as very much like the overnight transformation of an interested but untrained student into a medical doctor.Footnote 3 His sole motivation for establishing the newspaper was the promotion of the Yoruba language and culture, his own father being an Ijala (Yoruba hunters’ poetry) poet. His main target was the largely illiterate and semi-literate demographic of urban and grass-roots Yorubaland. But beyond convening a largely Yoruba audience, the paper's primary intention, following twentieth-century Yoruba writers, is to convene a nested scale of moral communities or an imagined ‘public’. The scope of this public is elastic enough to expand from such spatial boundaries as the smallest social unit in a family to cover the black race and ‘the four corners of the world’ (‘origun mereerin agbaye’), addressed individually or collectively. Thus, as Barber observes in a different but related context, ‘the Yoruba are the Egba writ large, Nigeria is Yorubaland writ large, and Africa … is Yorubaland writ even larger’ (Reference Barber1997: 124). Based on its concerns with political themes and its focus on moral discourse, Alaroye convenes a supranational community through a national and/or subnational Yoruba group (cf. Shipley Reference Shipley2009; George Reference George2003).

Before establishing Alaroye in 1979, Adedayo had worked with the Lagos State Broadcasting Corporation as a newscaster. He then worked with the Nigerian Television Authority's (NTA's) Channel 10 and Radio Nigeria, both in Lagos. He combined his severance pay after losing his job with the NTA with a loan from his wife to establish Alaroye. The one-man business model on which he set up the newspaper is popular across West Africa in the unstructured informal sector and followed the example of the proprietor-editors of the Yoruba newspapers of the 1920s. While Adedayo states that Alaroye made its debut in June 1985, the newspaper's web page places it at May 1985. Five months after it opened, in October 1985, Alaroye folded due to financial constraints. Its fourth edition had just rolled off the press. In 1990, five years after publication ended, the paper returned to the newsstands.

The return of the newspaper was planned with much pomp and circumstance, but the death of a prominent member of the community, a close friend of the publisher's main patron, on the day the newspaper was to be relaunched meant that the celebrations planned to usher it back to the newsstands were aborted.Footnote 4 With the entire community engulfed in mourning, the printed copies of the paper were not sold. Alaroye would not re-emerge again until 1994, when, after publishing four editions, it once again suffered financial setbacks and shut up shop. Things were to remain the same for two more years. By the time the publisher returned to the newsstands with Alaroye in 1996, events would conspire to assist his efforts. The national mood was one of gloom and uncertainty after three years of political crisis in the wake of the annulment, by General Ibrahim Babangida, of the 12 June 1993 presidential election. The crisis precipitated by the annulment would force Babangida out of office in August 1993. Then followed a short-lived interim administration led by another Yoruba man, Ernest Shonekan. But he was upstaged by General Sani Abacha in what is retrospectively viewed as a bloodless palace coup. By 1996, General Abacha had perfected a plan to stay on in government as a civilian head of state, and the Yoruba, who were at the forefront of the struggle to validate the electoral mandate given to Moshood Abiola, led the campaign to end military rule. Abacha, whose regime was one of the most brutal ever known in Nigeria, clamped down on the campaign with despotic force, and state-sponsored murder and hostage-taking, directed mostly at the Yoruba, became the accepted order of things. The fluid nature of the anti-military vanguard at this time resulted in alignments across ethnic, social and intellectual boundaries. In a sense, then, the re-emergence of Alaroye and its eventual success can be considered advantageous for the (Yoruba) intellectual arm within the wider context of protests led by human and civil rights groups against the Abacha dictatorship. Alaroye thus represented an alignment of elite and popular interests that came together under such groups as the Campaign for Democracy, Oodua People's Congress (OPC), Oodua Liberation Front, Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People and Movement for National Reformation, together with the press. Most of these groups would later coalesce under the umbrella of the National Democratic Coalition (NADECO). Alaroye’s own strategy at the time reflected Nolte's (Reference Nolte2007) observation about how the Yoruba educated and Christian elite of nineteenth-century Lagos reacted to British condescension and colonial rule by reasserting their dignity through an affirmation of the common history and culture of the Yoruba hinterland. Nolte's comment on the OPC, arguably the most militant arm of the various Yoruba self-determination groups, could well apply to Alaroye, which drew on the ‘tradition of enlightenment and cultural assertion within Yoruba cultural nationalism … to recentre the Yoruba nation’ (ibid.: 222) against the onslaught of the Abacha dictatorship.

The Nigerian press, with Lagos as its base, came under severe strain as draconian decrees aimed at muzzling it were passed. Soldiers laid siege to newspaper houses, carted off hundreds of thousands of news publications, hounded journalists into jail and killed others (Anyanwu Reference Anyanwu2002; Ajibade Reference Ajibade2003; Larr Reference Larr2011). Conventional journalistic practice in Nigeria was no longer safe and was at its nadir professionally, giving way to what is today known as guerrilla journalism, where journalists and media outfits operated underground with neither known nor fixed addresses. They published what Soyinka has called samizdat publications (Reference Soyinka2006: 406). Improvisation and invention were the order of the day as news publications changed their glossy look and took on forms and genres hitherto unknown.

After The NEWS magazine was banned and its press was shut down in 1993, its publishers launched TEMPO, which was initially conceived as a ‘soft sell’, human interest weekly. But, according to Ajibade (Reference Ajibade2003), it was immediately pressed into service to ‘carry on the mandate of The NEWS’ after the latter was proscribed. To make this clear to the public, the first edition was a replica of The NEWS – A4 size and glossy cover. The edition was scarcely off the press when it was carted off by agents of the military who invaded the offices of Independent Communications, publishers of The NEWS and TEMPO. The publishers responded by publishing the same newspaper as a tabloid. For Barber (Reference Barber2007), genre orients a speaker's or writer's utterance towards a listener or reader, and also orients the listener or reader towards the text. Producers of texts thus operate on the assumption that the receiver will identify the genre (ibid.: 32). And so it was with Nigerian journalists, their publications and their readers at this time.

At the time Alaroye entered the market in July 1996, many Yoruba politicians, including the eldest wife of M. K. O. Abiola, Kudirat Abiola, and other prominent women such as the Ibadan businesswoman and politician Alhaja Suliat Adedeji and the Iyalode Egba Bisoye Tejuoso had fallen victim to the Abacha regime. Both Adedeji and Tejuoso were shot dead in their homes while Kudirat was gunned down on a major highway in Lagos by Korean-trained agents of the Abacha killer squad led by Barnabas Jabila (popularly known as Sergeant Rogers) on 4 June 1996. This was barely a month before Alaroye was relaunched.Footnote 5 There was also a heightened sense of ethnic consciousness, a dynamic blend of ethnic solidarity and a suspicion of others from different ethnic backgrounds. Nigerians from other parts of the country, particularly easterners (Igbo) who had once been combatants and victims in the Nigerian civil war, moved out of Yorubaland as Yoruba people in other parts of the country returned home due to fears of another civil war.

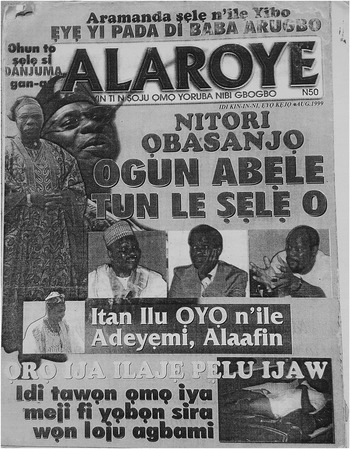

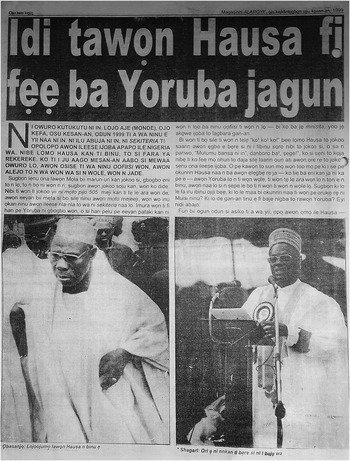

If Christianity and Western education spawned a common sense of Yoruba consciousness in the nineteenth century (Peel Reference Peel1978; Reference Peel2000), a sense that was reactivated by the Egbe Omo Oduduwa and the Action Group coalescing around Obafemi Awolowo from the mid-twentieth century (Adebanwi Reference Adebanwi2014), the unceasing beat of Abacha's war drums in the middle to the latter half of the 1990s revived this heightened sense of Yoruba nationhood and common destiny. More than at any other time in Nigeria's postcolonial history, the sense of being a Yoruba assumed greater dimensions in the 1990s. But as interpretive social science insists (see Adebanwi Reference Adebanwi2016: 31), any explanation of social and political life is essentially an interpretation, a fact illustrated by Alaroye’s cover reports of 31 August 1999 and 28 September 1999 (see Figures 1 and 2), respectively entitled ‘Nitori Ọbasanjọ ogun abẹle tun le sẹlẹ’ (‘Because of Obasanjo, another civil war could occur’) and ‘Idi tawọn Hausa fi fẹẹ ba Yoruba jagun’ (‘The reason the Hausa want to go to war with the Yoruba’). Both stories, which centre on the domination of political space by the Hausa-Fulani elite and the impoverishment of the Hausa-Fulani poor, as well as Nigerians more generally, come to basically the same conclusion: that the Hausa-Fulani would rather seek the breakup of Nigeria via war than submit to the leadership of any other ethnicity. The paper narrates further on its 31 September cover that ‘Nina owo yalayala ki i se ole lọdọ wọn’ (‘Profligate spending does not count as stealing among them’) and concludes that the Hausa-Fulani's loss of power – and thus their loss of access to and lavish use of Nigeria's wealth – is the reason why they seek war with the Yoruba. But although both stories are very detailed, they are basically a narrative reconstruction of Nigeria's history and the Hausa-Fulani's rise to political dominance. There is no evidence of the direct threat of war by the Hausa-Fulani, corporately or individually, in either story. Such an invocation of fragmentation or representation of ethnic difference – an ‘us versus them’ paradigm that Alaroye invoked in the example above and in others cited in this article – could be read in the context of what Giroux and McLaren (Reference Giroux and McLaren2014) and Modood (Reference Modood and Boxil2000) (quoted in Akpome Reference Akpome2017: 56) call cultural racism.

Figure 1 Cover page of Alaroye, 31 August 1999. Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, former Nigerian army general and military head of state (1976–79), elected president (1999–2007). Picture credit: Alaroye.

Figure 2 Page 8 of Alaroye, 28 September 1999. President Olusegun Obasanjo (left) and Alhaji Shehu Shagari, first executive president of Nigeria (1979–83) (right). Picture credit: Alaroye.

As well as the various news publications that set out to mobilize the Yoruba, and other Nigerians, against military rule, there were also pirate radio stations. The first of these was Freedom Radio, facilitated by General Alani Akinrinade of the NADECO opposition, while Radio Kudirat, with its wider reach, was founded by Wole Soyinka and his National Liberation Council with the technical support of the Swedish and Norwegian governments and the UK's Westminster Foundation (Soyinka Reference Soyinka2006). In mobilizing against the military, the Yoruba invested almost all they had in the fight, including their rich artistic heritage. Neo-traditional media poetry, ewi, whose heyday was in the 1970s, returned with vigour as the likes of Lanrewaju Adepoju, Kunle Ologundudu, Bayowa Adewusi, Deroju Adepoju and Gbenga Fajemileyin rose as with one voice in biting, excoriating protests against the Babangida and Abacha regimes (Olukotun Reference Olukotun2004; Okunoye Reference Okunoye2010).

It was into this atmosphere of tense political struggle and hegemonic contestation that Alaroye fell in 1996. It was an overtly and unapologetically political paper that was hugely successful. As is the case with most popular cultural products, Alaroye flourished despite official non-recognition. The unexpected success of Alaroye lay in the irony that its stability after ten long ‘abiku’Footnote 6 years of birth and rebirth would come via the draconian excesses of military dictatorship. The publisher who had had trouble convincing newspaper vendors in Ibadan (where he then lived) to accept his twelve-page, black-and-white Yoruba publication at a time when colour printing was increasingly becoming popular and the norm in the media would be surprised by the warm reaction from the public.

A genealogy of Yoruba newspapers: Alaroye in the longue durée

While newspaper culture in Nigeria started with the Church Mission Society's experiment with Iwe Irohin, a bilingual newspaper that was published in English and Yoruba, the vast majority of newspapers that emerged subsequently in Nigeria were published in English. In Yorubaland, the example of vernacular newspapers would not re-emerge with noticeable force until the 1920s, a period that witnessed a resurgence in Yoruba-language papers following a fateful and somewhat fortuitous blend of three factors: namely, Christian evangelism, cultural nationalism, and an expansion of the reading public (Falola Reference Falola1999; Omu Reference Omu1978; Barber Reference Barber2012). While Falola suggests that the resurgence was due to Christian evangelism, Omu and Barber respectively ascribe it to cultural nationalism and an expansion of the reading public. In varying degrees, each of these factors – the last two more than the first – contributed to a revival of interest in Yoruba-language newspapers.

The Iwe Irohin experiment ended when the newspaper stopped publishing eight years after it was established in 1867. Although the print culture it inaugurated would spawn several newspapers, pamphlets and books on a diverse range of subjects from Yoruba history, religion and literature in Yoruba and English, it was not until the 1920s that the press experienced a boom in popular readership as it expanded the scope of its operations. This was the era of proprietor-editors, when the same person founded, owned and edited each paper. The first to emerge in 1922 among the Yoruba papers was Eko Akete, founded by Adeoye Deniga, followed in 1923 by Eleti Ofe, owned by E. A. Akintan. In 1925, T. H. Jackson, who had edited the Lagos Weekly Record, founded Iwe Irohin Osose, to be followed by E. M. Awobiyi's Eko Igbehin in 1926. Akede Eko was launched by I. B. Thomas in 1928. One of Thomas's experiments with genres in his paper, the serial letter-writing format, would lead to his highly popular and, at the time, controversial narrative of the life of an ailing prostitute that retrospectively was regarded as the first Yoruba novel: Itan Igbesi-Aiye Emi ‘Segilola Eleyinju Ege’ Elegberun Oko L'aiye. The point needs to be underlined that Alaroye operates within a vernacular newspaper culture that is not altogether new. The debt Alaroye owes these older papers is attested by the fact that the highly popular ‘Yetunde Oju-to-n-soro’, a column in the early Alaroye (now moved to Akede Agbaye), was apparently influenced by and modelled on I. B. Thomas's Segilola. Some of the leading Yoruba newspapers, followers of Alaroye, today have columns modelled on the ‘Yetunde Oju-to-n-soro’ column.Footnote 7

A few attributes defined these earlier newspapers, and some of them appear to have influenced Alao Adedayo and had a lasting effect on his journalism. While the Saros and Agudas (Sierra Leonean and Cuban/Brazilian repatriates) dominated the professions (medicine, law, engineering, architecture and surveying) (Adeboye Reference Adeboye, Falola and Genova2006), there was a new pool of lower-level white-collar workers, including clerks, bookkeepers and printing assistants, who were drawn into the expanding civil service and public works from among the burgeoning population of school leavers. It would seem that the majority of Yoruba newspaper owners were drawn from among this class of workers. Others in this category were the commercially frustrated local elite, the unemployed, and others sacked from companies owned by Europeans (Agbaje Reference Agbaje1991: 42). Self-trained and of diverse backgrounds, they seemed imbued with more zeal than skill and apparently had to learn on the job. There was a high rate of attrition among the newspapers, with many folding soon after they were established. But a few of them, such as Akede Eko, had a relatively long life, publishing for over twenty years and well into the 1950s. In terms of their organizational structure, the newspapers were like the artisan-dominated, small-scale entrepreneurial enterprises that were to be found in the West African informal sector. They were financially precarious businesses. Some of the experiments, improvisations and inventiveness that entered the practices and business culture of these papers were influenced by their precarious financial base. Unlike a few of the English-language newspapers of the 1920s that appeared daily, the Yoruba papers were weeklies; like the English papers, they were mostly written by their owner-editors. In spite of their weekly status, they were always in need of copy and thus solicited for contributions and responses from their readers. As was the case with Akede Eko, some of these papers often failed to make it to the newsstand for various reasons, such as poor subscription rates and the failure of salesmen to send in their takings.

The precarious existence of the Yoruba papers of the 1920s did not improve with their successors in the post-independence years, except for those affiliated to political parties (Agbaje Reference Agbaje1991). The 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s ushered in such newspapers as Gbohungbohun, Yoruba Ronu, Ajoro, Akede, Isokan and Alaroye. While these newspapers existed, financially, on a precarious basis, they seemed to have suffered more from poor patronage due to the low esteem associated with the language in which they were published. Alaroye, however, has proven to be the lead title, typifying the tradition and culture of Yoruba-language newspapers in the last decade and a half. Alariya Oodua, closely followed by Iroyin Owuro, is the leading new entrant in the Yoruba newspaper sector. Both are keen followers of the new Yoruba tabloid tradition pioneered by Alaroye.

Alaroye as popular art

African popular arts have been theorized as a ‘fugitive category’ and site of contested evaluations. This, therefore, calls for a nuanced, integrative and incorporative reading of the field of cultural production in Africa (Adelugba Reference Adelugba and Adelugba1986; Sekoni Reference Sekoni and Ogunbiyi1988; Julien Reference Julien1992; Nnodim Reference Nnodim, Ricard and Veit-Wild2005). It is for this and for related reasons set out below that I have ‘read’ Alaroye as popular art. Although it is a newspaper, over the years Alaroye has assumed the status of a popular art form and is often referenced in Yoruba popular culture. It combines the dimensions of sociological popular culture with the aesthetic arts (Barber Reference Barber1987: 5). The circumstances of its emergence on the Nigerian newsstand in an era of military dictatorship and the circumscription of press freedom, on the one hand, make Alaroye a popular form. But no less significant, on the other hand, is the fact that the Alaroye genres are generally labile, sometimes ludic, and often driven by a populist sensibility, which explains the speed at which they incorporate innovations, just as these innovations and the genres in which they are given expression are constantly refined, transformed and/or recycled as circumstances dictate. As a written form that is not only embedded in a largely oral domain but embodies oral aesthetics, Alaroye resides at the intersection between Africa's traditional and elite art, thus manifesting the syncretism that is, perhaps, the most distinguishing feature of the new art of colonialism. In addition to this, and in addition to being a creation of ‘the people’, Alaroye is affordable, quasi-oppositional and unofficial, especially at the point of its emergence and in terms of its innovations, which tend to evade or invert the dominant ideology. All of this has given it a unique place in vernacular newspapers in particular and in Nigerian journalism in general. Finally, Alaroye is informal and its language practice, which aims to write Yoruba the way it is spoken, is both fresh and simple, with the most minimal concession to what might be called the ‘standard’ phonetic/phonological demands of the Yoruba language, thus making it appealing to the ‘lowest common denominator’. But, more importantly, its experimental innovations exist within a traditional Yoruba cultural philosophy that privileges the new, the experimental and the inventive.

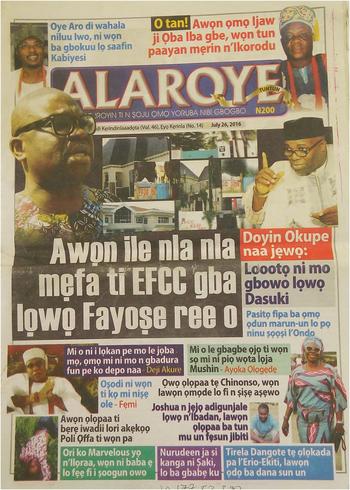

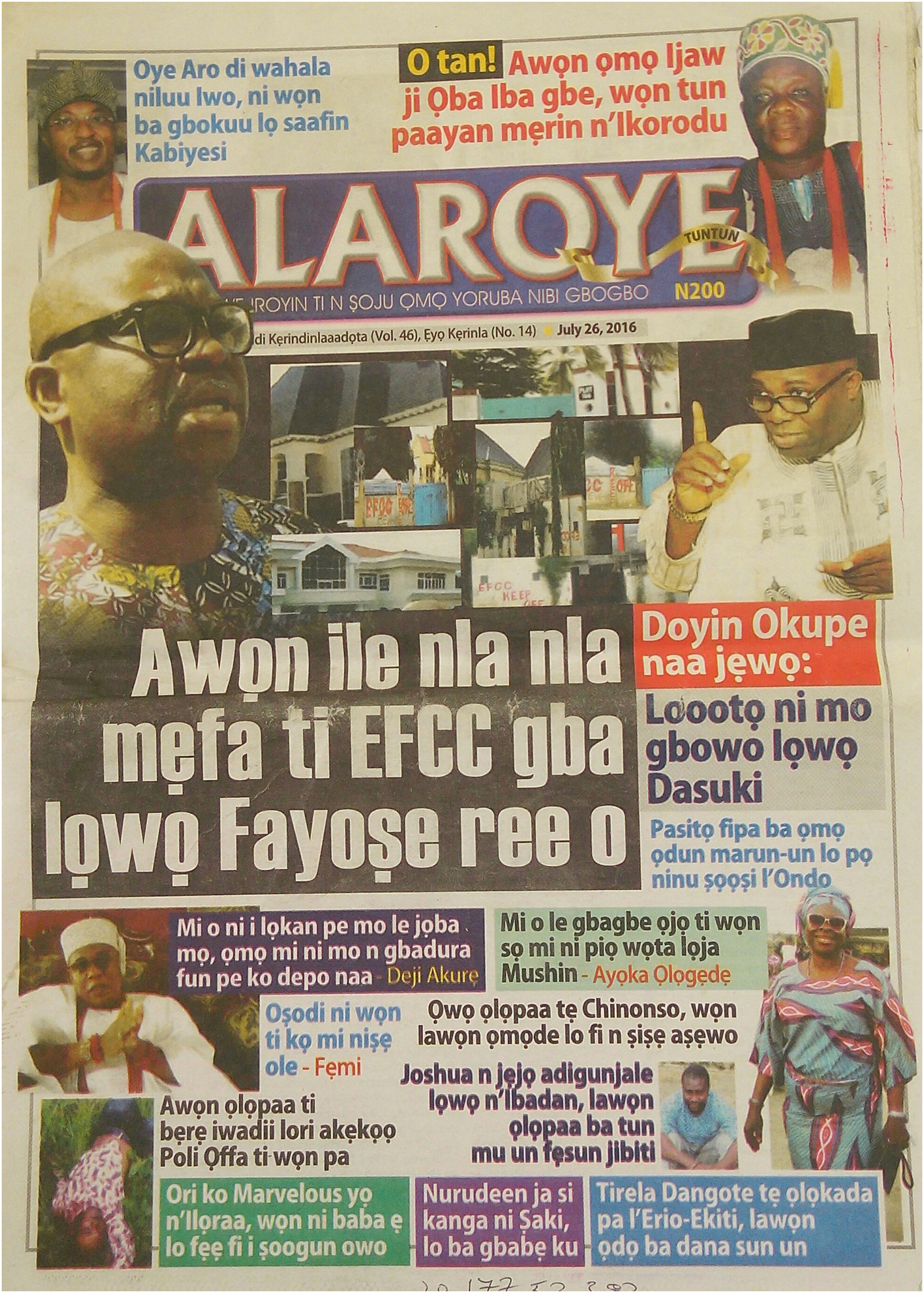

The paper's populist sensibility is often on display on the cover page, which is packed tightly with screaming headlines or riders that are accompanied with very graphic and colourful photographs. The reader is directly hailed and interpellated by human interest stories, highly political news and entertainment-oriented or outrageously salacious features that are juxtaposed on the page to create a very tight, somewhat playful, often contradictory mix – a postmodernist pastiche that erases any form of elitist or hierarchical differentiation. This is evident in the paper's edition of 26 July 2016 (see Figure 4). Samuel Ogunlusi (aka SOS), a reader of Alaroye for ten years, finds this style of report with its direct address to the reader very attractive. For him, the accompanying images authenticate the stories and lend credence to Alaroye’s reports, which, according to him, are distinguished by ample detail. Such close attention to detail and the historical slant the paper gives to political stories are qualities that both Emmanuel Olufemi Adegbite and Ibrahim Ademola,Footnote 8 two other readers of Alaroye, find admirable. Headlines such as those of 15 January 2013 (see Figure 3) entitled ‘Iku Bisi Kọmọlafẹ di wahala. Eyi ni idi ti awọn mọlẹbi ẹ fisọ pe ọkọ rẹ lo pa a’ (‘Bisi Komolafe's death results in trouble. This is the reason why her relations say her husband killed her’) or ‘O ga o! Fatoke, onijita Sunny Ade tẹlẹ gbe oogun oloro’ (‘This is serious! Fatoke, former guitarist of Sunny Ade traffics hard drugs’) are directly addressed to readers. In the same vein is the headline of 3 October 2017, accompanied by a large image of Aliko Dangote (see Figure 5), a Hausa-Fulani who is reputedly Africa's richest man, in the ‘Omo odo Agba’ column on the back page of Alaroye: ‘Ẹyin ọmọ wa, ẹ farabalẹ ki ẹ̀ kọgbọn o’ (‘You children of ours, stay calm and learn wisdom’). The entire story is a warning to the younger generation of Yoruba people to be wary of the way the Muhammadu Buhari administration has been promoting the business interests of Aliko Dangote in the overall scheme of Hausa-Fulani domination of Yorubaland. The writer thus concludes: ‘Ohun ta a se n beere atunto ree, kawọn Hausa-Fulani yee rẹ awa ẹya to ku jẹ’ (‘This is why we are clamouring for restructuring, so the Hausa-Fulani would stop cheating the rest of us’).

Figure 3 Front cover of Alaroye, 15 January 2013. Picture credit: Alaroye.

Figure 4 Front cover of Alaroye, 26 July 2016. Picture credit: Alaroye.

Figure 5 Back page of Alaroye, 3 October 2017. Africa's richest man, Alhaji Aliko Dangote. Picture credit: Alaroye.

Genres and innovations in Alaroye

The formation of genres occurs in the zone of addressivity constituted by the mutual orientation of the text to the audience and the audience to the text … New genres take shape as writers/composers of texts convoke new audiences … and, at the same time, the people out there bring new expectations to bear on texts, responding in new ways. Emergent genres and emergent constituencies come into being in response to each other. (Barber Reference Barber2007: 138)

At its inception, Alaroye was a twelve-page paper printed in an A4 magazine format and sold for just 20 kobo, about half the cover price of an average English-language newspaper. The front page was filled with ‘screaming headlines’ that announced ‘important stories’ in the paper. Page two focused on strange events while page three was for current news. ‘Page four was the editorial page, while pages five, six and seven extensively dealt with the lead story. The lead story would begin from some happening in the past, link it with the present situation and predict the consequence in the future’ (Adebayo Reference Adebayo and Salawu2006: 203). The regular items of the paper, some of which have undergone various metamorphoses in the last two decades, include ‘Omo Yoruba Atata’, ‘O-soju-mi-koro’ and ‘Yetunde Oju-to-n-soro’. In the wake of Alaroye’s coming ‘on top’ – that is, breaking even economically and attaining mainstream prominence in Nigeria – as Taiwo Adedayo, the general editor of the paper put it, the latter column has been moved to a sister publication in the Alaroye stable, namely Akede Agbaye, which was established as a fast-track, ‘breaking news’ publication in 1998.

In 2010, Alaroye was renamed Alaroye Tuntun (New Alaroye), with twice as many pages as in the past, four of them in colour, something that gives it an edge over rivals. The paper itself is printed by Punch,Footnote 9 the prominent tabloid founded in 1973 by James Aboderin and Sam Amuka, and is generally rated as Nigeria's largest-selling newspaper. ‘Iya Abiola Oniresi L'Osodi’ (‘Mother of Abiola the rice seller in Oshodi’), a gossip column written by a respected housewife, has replaced ‘Yetunde-Oju-to-n-soro’, and is balanced in the ‘new’ Akede Agbaye with another column detailing the sexual escapades of a male gigolo, Alabi Denja (‘denja’ being a pun on ‘danger’).Footnote 10 Both columns used to appear one above the other on the same page in Alaroye before the changes in page layout and content. With the name change from Alaroye to Alaroye Tuntun has come a marked reduction in the sensationalism of the newspaper's headlines, a marker of its so-called ‘junk’ journalism. The paper has toned this down and has moved somewhat towards the more ‘responsible’ end of the journalistic spectrum.Footnote 11 The sensational is still reported, but from the angle of odd life events or occurrences, strange or unusual happenings and experiences (iriri aye) that inspire wonder, shock or surprise. One of the defunct publications in the Alaroye stable was Iriri Aye Alaroye, which had a bent for reporting strange, unusual and sensational occurrences. The gradual expansion of its audience base, due to its popularity, has led to an increase in the number of titles from the publishers of Alaroye, each publication set up for different reasons and directed at different (but sometimes the same) audiences, and, to a greater or lesser degree, all influenced by – if not conceived for – economic reasons. These publications have undergone various transformations at different times in accordance with the social and economic agenda of the publisher. While Akede Agbaye was originally a highly political, ‘hard’ news publication established to fill the ‘gap’ created by the sudden demise of Sani Abacha, it has since transformed into a human interest publication that chronicles the activities of Yoruba film celebrities and entertainers and other ‘soft’ stories. Alaroye Kwara was founded to tap into the market created by the falling-out between the late Olusola Saraki, ‘godfather’ of Kwara politics, and his protégé, Mohammed Lawal, a former governor of the state. The intention of the Alaroye publisher was to use the political struggle between the two politicians as a way to establish Alaroye in each of the Yoruba-speaking states of Nigeria. Kwara was thus a ‘testing ground’.

The idea of Alaroye Magazine came about because of the publisher's need to correct the observable disadvantage in selling Alaroye, the newspaper, for half the price of English-language newspapers. The shortfall in cover price meant, according to the newspaper's website, low-quality production and cramped pages chock-full with reports, even though interviews were short and the paper lacked in-depth reports, analysis or features. Alaroye Magassini, a twenty-eight-page monthly publication that appeared on the last Tuesday of every month, was their answer to this problem. The first edition of 120,000 copies, which came out in August 1998 and sold for 50 kobo, chronicled the life story of M. K. O. Abiola. It is instructive that the idea of starting a new ‘magazine’ should occur to the publisher of Alaroye in August, for, aside from the fact that Abiola had died in controversial circumstances only a month before (on 7 July), August was also his birth month (his birth date was 24 August). This was obviously another politically smart move influenced by economic considerations and the Yoruba penchant for memorializing important events. In accordance with the ever-changing agenda of the ‘Alaroye Group’, Alaroye Magassini has been discontinued, replaced with a newspaper that is published once every three months and was apparently modelled on Alaroye Magassini: it is called Akanse Alaroye (Alaroye Special).

Alaroye's oral written style

The genre-blurring innovations Alaroye has brought into the Nigerian newspaper market, with its radical blending of Yoruba oral resources with a written medium and its mixing and/or switching of codes and borrowings from the English language, blazed a trail that several other publications have since followed. This strategy is bolstered by the introduction and increased popularity over the years of such daily newspaper review programmes as ‘Koko Inu Iwe Iroyin’, ‘Eleti ofe’, ‘Oju tole oju toko’, ‘Ongbonan felifeli’ and ‘Kilon sele?’ The ‘communal’ review of newspapers on these radio programmes serves to oralize a written genre. Some Alaroye strategies that are amplified on these daily newspaper review programmes include screaming, sensational headlines – very much in the fashion of a Yoruba town crier or a female hawker, screeching, in the words of Adebayo (Reference Adebayo and Salawu2006: 198), ‘Mo gbe de, e wa ra a o!’ (‘Please come over and buy my wares’); and a bias for political stories, complemented by generous graphics and photographs in a manner hitherto unknown in an indigenous-language newspaper, with ‘the current orthographic arrangement blended with its own style of writing the language the way it is spoken’ (ibid.). The screaming headlines, as in previously cited examples, approximate the speaking voice of the traditional town crier. Alaroye also provides specialized reporting on various sectors of society. Mrs Adeniran,Footnote 12 a regular reader, is impressed that Alaroye organizes debates on Yoruba language and raffle draws in addition to providing extensive reports on Yoruba film and music celebrities. Alaroye can be described as a complex of genres, a single newspaper that addresses multiple audiences, although its primary audience is undeniably Yoruba. The publishers of Alaroye simplify and suppress the complexities of oral tradition, especially in the way in which the newspaper is written with the purpose of convening a pan-Yoruba print public. In addition to its oral written style, this simplification takes the triple form of a deliberate conversational tone, borrowings from the English language, and minimal use of tone marks – all of which has resulted in a generalized tabloidization of the newspaper and a simplification or ‘dumbing down’ of the standard Yoruba language in which mainstream publications such as Alaroye ought to be written. The insertion of proverbs or invocations of a shared cultural experience are typical of Alaroye’s strategy of interpellation. An example is this report of 12 February 2013 of a notorious Nigerian cleric, Chukwuemeka Ezeugo, aka Reverend King, who was charged with the murder of some members of his church and sentenced to death:

BEEYAN ba n yọlẹ i da, ohun abẹ̀nu a maa yọ ọ se. Bẹẹ si ni ironu ọlọgbọn atawọn onilaakaye ki i yatọ, tomugọ eeyan nikan ni ki i jọra wọn. Njẹ ẹ ti gbọ pe ile-ẹjọ ko-tẹ-mi – lọrun paapaa kọyin si Rẹfurẹndi King. Pasitọ ti wọn fẹsun ipaniyan kan lọdun bii meje sẹyin, tile ẹjọ giga Ebute-Mẹta dajọ iku fun lọdun 2006, to si se bẹẹ to pẹjọ ko tẹ-mi – lọrun lori idajọ yii, gbogbo kukukẹkẹ ti fẹẹ pin bayii, nitori ile-ẹjo naa lawọn fọwọ si idajọ iku yii, ki Pasitọ naa maa lọ sibi to ran ọmọ ijọ rẹ lọ.

Those who sow evil will surely reap evil. The thoughts of the wise and the knowledgeable are always in tandem, only those of the foolish are without basis. Have you heard that even the Court of Appeal has found Reverend King, the pastor charged with murder a few years ago, the one that was sentenced to death in 2006 by an Ebute-Meta High Court, who appealed against the judgment, his arrogance has almost ended as the court has upheld the death sentence against him, that Pastor King should go to the same place he sent his church members.

A direct mode of address, as in the above example, and the use of contracted forms are additional markers of Alaroye’s conversational or informal style. The resort to proverbial utterances allows readers to learn ‘deep’ Yoruba, thereby serving the additional purpose of exposing readers, especially non-Yoruba such as Kingsley Onoja,Footnote 13 to the best form of contemporary Yoruba.

Alago oba: Alaroye as a modern-day town crier

Alaroye’s oral written style enables the continuation of what Barber (Reference Barber and Barber2006: 18–21), in a related but different context, calls ‘cultural editing’, a project begun by an earlier generation of Yoruba cultural nationalists and that was aimed at promoting the Yoruba as one homogeneous people united by one culture and one language. According to Barber, writing provides a motivation to refashion what is being written down in a way that allows for the separation of the legitimate from the illegitimate, while ensuring that the separation between the two is permanent. Alaroye inserts itself into a ‘ceremonial space’ that was once wholly inhabited by an oral artist – in this case, the alago oba (the chief messenger, spokesperson or town crier). This was a royal position that is equivalent to the modern chief's press secretary or the spokesperson of a sovereign or government. In a democratic age dominated by the elected representatives of the people and in which the influence of the traditional monarch has been reduced tremendously, the newspaper presents itself as both the monarch and the modern spokesperson or representative of the sovereign. In its present form, the newspaper epitomizes the role of the town crier in a traditional Yoruba community, hence its slogan ‘Iwe Irohin t'o n s'oju omo Yoruba nibi gbogbo’. The screaming headlines, as in previously cited examples, approximate the speaking voice of the traditional town crier. In its self-imagined role as the sole representative of the people, Alaroye also serves as a watchdog, the authoritative voice of truth that protects the people against the abuse of their leaders. In the spirit of post-structuralist thought, however, Edward Said (Reference Said1979: 21), drawing on Michel Foucault's archaeological discourse, asserts that truth is not equivalent to its representation. Thus, in spite of Alaroye’s claim to being the representative of the Yoruba people, its narration of history remains no more than a representation of the ‘truth’. Rather than concentrating on the meaning it purveys, therefore, attention should be focused on analysing the factor – or factors – that enables its version of reality or the strategy by which it arrives at that version. This is where its linguistic, extra-linguistic and visual strategies come into play, strategies through which it has attracted a relatively large readership. Based on such considerations, Alaroye’s narration can be placed in context and read as a representation of truth rather than as absolute truth. It should also be noted that, as a written form, Alaroye’s disquisitions can be preserved for a much longer period compared with the message of the alago oba, which is more evanescent and is lost as soon as it is uttered.

While viewing oral texts as an attempt to fix words and give them a lasting existence, oral texts have also been described as a demonstration of the emergent and improvisatory. Thus, the language of a text such as Alaroye, which is written the way it is spoken or in the voice of a speaking person, is both a recognition of language and a conscious attempt to animate it by infusing life into an otherwise ‘lifeless’ utterance. In How to Do Things with Words (Reference Austin, Urmson and Sbisa1962), J. L. Austin observes that the central purpose of language is to do things: that is, to give a ‘real life’ effect to certain linguistic acts. For Austin, the vast majority of human utterances do not have truth value; rather, they are used to perform actions or ‘speech acts’. This gave rise to the idea of ‘performative utterances’ or ‘performatives’, which, rather than merely saying something, are indeed intended to perform certain kinds of action. As he explained it, a performative (derived from the word ‘perform’) ‘indicates that the issuing of the utterance is the performing of an action’ (ibid.: 6). To read a written text such as Alaroye as if it were spoken is similar to performing a speech act, which in effect amounts to invoking nommo, ‘the life force’ (Jahn Reference Jahn1961), with performative effects, in the shape of the word that gives life to all things. This corresponds to the character of the Yoruba ase: ‘the power of words’ (Weate and Yusuf Reference Weate, Yusuf, Falola and Salm2003), ‘utterance-efficacy – that which enables what is appeased or/and invoked to come to pass’ (Olorunyomi Reference Olorunyomi2005: 144), or ‘the magic power of the word to call things into being’, as Handley (quoted in Bergthaller Reference Bergthaller2007) refers to it in a related context. In this context, simulating orality is a process of reifying logos, a bold affirmation of the originary status of language (or even life) as speech. It is, by implication, a reassertion and re-inscription of the agency and/or autonomy of Yoruba – or even African – oral tradition in a predominantly scriptocentric age.

Conclusion

This article has explored the emergence and stabilization of Alaroye, a Yoruba-language newspaper, in the context of a military dictatorship. The leadership of the media market by the English-language press and the marginalization of Yoruba-language newspapers – and, indeed, the Yoruba people – placed Alaroye in very precarious circumstances as the publisher stumbled from one financial crisis to another and failed to break even. The newspaper's challenge of military rule and its mobilization of meaning under and against an oligarchy dominated by the Hausa-Fulani would be significant in its eventual rise and success. This followed the annulment of an election judged to be free and fair that had been won by Yoruba businessman M. K. O. Abiola. The steady escalation of attacks against the Yoruba and the suppression of the free press and civil society created a palpable atmosphere of ethnic consciousness. The struggle of the Yoruba for self-determination and their contestation of military rule bolstered the newspaper's construction of hegemony in its self-imposed role of representing the Yoruba people and (re)presenting reality. Alaroye’s innovative deployment of language and its journalistic style were shown to rest on an established tradition of Yoruba journalism. In concluding, the article has examined the genres of Alaroye and the innovations introduced by the newspaper, all of which heralded and accelerated its gradual but steady transformation from a nondescript, magazine-style publication into a tabloid of formidable social and political significance. I have further demonstrated that Alaroye’s screaming headlines and its direct mode of address, which implicates the reader in the narration of events, coupled with its deliberate insertion of proverbial sayings and its generous use of graphic images have not only helped enhance the newspaper's popularity and position as a market leader but are also postmodernist markers of its oral written ‘house’ style and today are being emulated by other Yoruba-language newspapers.

Acknowledgements

I wish to extend my profound gratitude to the following: Ayodele Abeo Fasan; the African Humanities Programme (AHP); fellows and mentors of the 2016 AHP Manuscript Development Workshop in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; the Department of African Studies and Anthropology, University of Birmingham; Carli Coetzee; and the anonymous reviewers.