1 Introduction

1.1 Calling All Influencers

Visitors to the US Capitol building in Washington, DC, on March 22, 2023, were greeted by a curious scene. A group of demonstrators chanted slogans, bore placards, and spoke to a group of reporters gathered at the scene. But their immaculate hairstyles, expensive watches, and luxury sunglasses betrayed that these were not campaigners against war or racial injustice. They were social media influencers, and their demand was to ‘Keep TikTok’. They hoped to influence congressional representatives as they debated the fate of the short video app.

Inside Congress, lawmakers grilled TikTok’s US CEO, Shou Zi Chew, on the company’s handling of US citizens’ data, the nature of its relationship with its Chinese parent company ByteDance, and its purported links to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The demonstrators outside were unable to influence the mood on Capitol Hill. Evidently unsatisfied with Mr. Chew’s answers, in March 2024, the Senate passed a bill forcing ByteDance to sell its stake in TikTok or face a ban on operating in the United States. The ‘TikTok Bill’ (Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act, PAFACA) will help ensure that the US digital media ecosystem remains under firm control of domestic firms like Meta (Facebook), X (formerly Twitter), and Google.Footnote 1

These events are illuminating for three reasons. First, they highlight how growing concerns about the social power of digital media platforms – including their data collection and sharing practices, and the impacts of their algorithms on public life – are increasingly driving oversight and policymaking efforts. Second, they represent the US government’s political response to TikTok, which is the first major Chinese digital platform to succeed in the US market (since followed by retail platform apps such as Shein and Temu). The case suggests the United States is willing to use the full spectrum of its policy toolkit to inhibit Chinese platforms from gaining market share in the United States, and to protect the dominance of its digital platform firms against Chinese competitors. Third, they demonstrate that platforms have become increasingly central to the broader US-China geopolitical rivalry, a competition which is increasingly reshaping world politics and the economy.

How did apparently innocuous internet platform companies like TikTok, Meta, and Google – known principally for their banal functionalities like short video content and search optimization algorithms – become entangled with the logic of a global geopolitical conflict? As we show in the following pages, platforms increasingly provide the infrastructure undergirding the world’s social and economic networks. Not only do they facilitate and intermediate the countless exchanges that comprise much of daily life, but they increasingly hold the power to (re)shape how, and even to decide if, these interactions take place. This infrastructural role affords them tremendous power, because they write the rules – both metaphorically and literally, in devising their ‘terms of service’ – by which other social and economic agents interact. If ‘code is law’, as Lawrence Lessig (Reference Lessig2000) once wrote, then platforms represent planetary-scale judiciaries. What is more, platforms’ infrastructural power – manifest in their vast capital, compute, and data resources – is placing them at the centre of the global race to develop and commercialize artificial intelligence (AI) (Nitzberg and Zysman, Reference Nitzberg and Zysman2022; van der Vlist et al., Reference van der Vlist, Helmond and Ferrari2024).

This steady accumulation of power by platform firms has not gone unnoticed in the corridors of political power. But, as we aim to demonstrate, the response to growing platform power from politicians has not been entirely hostile. In addition to curtailing some of the powers their domestic platform firms wield at home, governments in Washington, Beijing, and elsewhere have concurrently sought to bolster the global standing of their largest platform firms abroad. In this way, states are beginning to recognize the large potential for multiplying their power which can derive from harnessing platform infrastructure for public ends. And although platform firms are often hostile to new regulatory initiatives and regimes, they have increasingly partnered with states because of the economic and regulatory advantages that this affords.

1.2 Conflict and State Capitalism

Digital platforms did not arise in a vacuum. Their rise to become global economic powerhouses was propelled by the rules and institutions that underpinned neoliberal globalization in the 1990s and 2000s. The basic principle of US power after the Cold War was to open the world’s markets ever more deeply to free flows of investment, trade, and information. With the ‘Washington Consensus’, US policymakers pushed states towards ever-greater marketization, dismantling the edifice of post-war statism, and empowering global institutions such as the WTO to invigilate these new rules. The United States privatized the networking infrastructure which had emerged through its efforts to interconnect local networks under the auspices of D/ARPA, while encouraging (through consent and coercion) third countries to follow suit (Tarnoff, Reference Tarnoff2022). The new US internet firms which emerged consolidated market power by amalgamating the hitherto local networks built up within the United States into a national ‘internet’. But they also spread rapidly across borders and markets, protected by a global IP regime and encouraged by the liberal prescriptions for the world to pursue development and growth through networked integration (embodied by the WTO’s 1997 Basic Telecommunications Agreement).

Neoliberal globalization was underpinned by optimistic narrative of liberal peace underpinned by economic integration. In this ‘flat’ world, developing countries would supposedly be unencumbered by the demands of great powers or threatening neighbours. In exchange for opening their markets to firms from the developed countries, they could leverage their distinctive advantages to achieve growth and prosperity. Transnational economic integration instantiated a ‘partial shift of some components of state sovereignty to other institutions’ such as multinational corporations and international organizations (Sassen, Reference Sassen1996, 146).

However, neoliberalism did not simply erode state power (Comunello and Mulargia, Reference Comunello and Mulargia2023). Rather, some states and some firms gained considerable influence and control over the strategic flows and nodes that underpinned global networks, even as others saw their power wane. So even while economies became increasingly interdependent through radical increases in flows of goods, trade, and investment, power relations remained profoundly asymmetric. Critically, the United States was able to maintain its handle on many (if not all) of the key ‘chokepoints’ within transnational networks.

Much of this new architecture of networked power remained hidden from view until conflicts over networks burst into the open during the first Trump presidency (Farrell and Newman, Reference Farrell and Newman2023). Trump’s first administration made clear that great power competition had not been superseded by globalization. Since he launched his ‘trade war’ on China early during his first term, the United States and China have become locked in an increasingly intense and all-encompassing rivalry increasingly analogous to the Cold War (Schindler et al., Reference Schindler, Alami and DiCarlo2024). But in contrast to the Cold War, which produced a world divided economically into largely isolated territorial blocs, contemporary geopolitical rivalry is unfolding in the networked world that globalization built (Schindler and Rolf, Reference Schindler and Rolf2024). Rather than a great unravelling of globalized networks, events since 2016 have driven states to radically expand their definitions of national security to include the ability to secure supply chains, access internationally integrated financial systems, and develop new technologies in innovation networks (Drezner, Reference Drezner2024). This expansive definition of national security – while it has encouraged states to make ever-deeper interventions to securitize their economies – has not yet undermined globalization in aggregate (Babić et al., Reference Babić, Dixon and Liu2022).

The state capitalist tools to which states have turned in pursuit of security and/ or geoeconomic leverage have deeper roots in the decades-long downward trend in global economic growth. The aforementioned neoliberal market reforms which drove globalization were supposed to allocate resources more efficiently and revive economic dynamism, but the results were underwhelming. The 2008 global financial prompted dramatic and long-lasting fiscal and monetary interventions to stabilize their economies and maintain liquidity. The quantitative easing undertaken by the US Treasury, combined with China’s stimulus spending, came to represent more of a new paradigm than stopgap measures. State-owned enterprises have experienced a comeback as states sought to pursue strategic investment programmes (IMF, 2020), and well-endowed sovereign wealth funds have purchased large stakes in leading private firms. Large-scale infrastructure investment also made a revival (Schindler and Kanai, Reference Schindler and Kanai2021), in part as a way of mopping up surplus capital, while the complex central bank financial engineering required to prop up stock markets in 2008 never went away – resulting in perennial asset price inflation (Adkins et al., Reference Adkins, Cooper and Konings2020). The economic and financial crises driven by the COVID-19 pandemic simply deepened these interventionist trends in both countries and beyond (van Apeldoorn and de Graaff, Reference van Apeldoorn and de Graaff2022).

Taken together these trends have been labelled as a ‘new’ form of state capitalism (Musacchio et al., Reference Musacchio, Lazzarini and Aguilera2015; Alami and Dixon, Reference Alami and Dixon2020b), most notable for the way in which it goes far beyond simple state-ownership to encompass a variety of novel interventionist strategies. And state capitalism has become wrapped up with geopolitical competition, as states vie to secure their economies against rivals through ever greater and deeper interventions (Alami et al., Reference Alami, DiCarlo, Rolf and Schindler2025). The emergent result is the rise of an increasingly multipolar world order, both increasingly geopolitically-fragmented while nevertheless marked by ‘deep’ forms of international economic integration both inside and between blocs (Lewin, Reference Lewin2024; Mezzadra and Neilson, Reference Mezzadra and Neilson2024; Wijaya and Jayasuriya, Reference Wijaya and Jayasuriya2024). State capitalist practices and their geopolitical corollaries have begun to remake the platform economy in dramatic new ways.

1.3 Platforms in the Ascendancy

State capitalism wasn’t the only major development to grow out of the 2008 global financial crisis. In the years of stagnation which followed, investment capital flooded en masse into the US tech sector. This fuelled an unprecedented investment boom, as start-ups sought to ‘hyperscale’ their way to market dominance by leveraging freely flowing venture capital (Klinge et al., Reference Klinge, Hendrikse, Fernandez and Adriaans2023; Varoufakis, Reference Varoufakis2024).

Big tech and the proliferating platform business model represented the best venue for capital seeking out returns in a broader environment of stagnation (Rikap and Lundvall, Reference Rikap and Lundvall2021). Rather than competing in oversaturated markets for particular product lines, platforms compete with one another to intermediate social and economic exchanges between users at scale (Srnicek, Reference Srnicek2017). For platform firms, securing first-mover advantage is a matter of survival because they operate in ‘winner-take-most’ markets (Brynjolfsson and McAfee (Reference Brynjolfsson and McAfee2014). Success often means establishing a ‘digital ecosystem’ that serves as a ‘market maker’ insofar as users are locked in, network effects take hold, and rival platforms struggle to attract users or complementors (Gawer, Reference Gawer2022). After the 2008 crisis, the abundance of cheap capital combined with rock-bottom interest rates allowed platform firms to expand at breakneck speed. Profits became virtually passé as platforms focused on ‘growth at all costs’ – and often at exorbitant cost to investors. Capital was ploughed into (making or buying) innovations in software, but also very tangible assets such as data centres and network infrastructure. While they were slow to come, the gains being chased were real for those platforms that could establish a dominant position. After years of losses, Silicon Valley giants like Facebook, Google, and Amazon generated $90 bn in profits in the pandemic year of 2020 (Tarnoff, Reference Tarnoff2022).

As platform firms have proliferated, they have come to intermediate an ever greater quantity of routine social and economic interactions. The burgeoning ‘platformization’ of everyday life means ordering food, hailing a cab, messaging a friend, or paying for goods is increasingly difficult – if not impossible – without the exchange being intermediated by one (or many) US technology firms. It is not just consumers who cannot avoid the platform giants. Global businesses and governments too have come to depend upon the data centres, software, networking equipment, and financial technologies owned and operated by platform giants to conduct their everyday business. Platforms have consequently become the critical infrastructure upon which other sectors of the economy and society rely for their everyday functioning. The newfound powers of such ‘private infrastructure’ providers have led to growing concern for state sovereignty and capacity (Rahman, Reference Rahman2018). Some have argued that their power has grown so large that they have suspended the rule of capitalism altogether (Varoufakis, Reference Varoufakis2024).

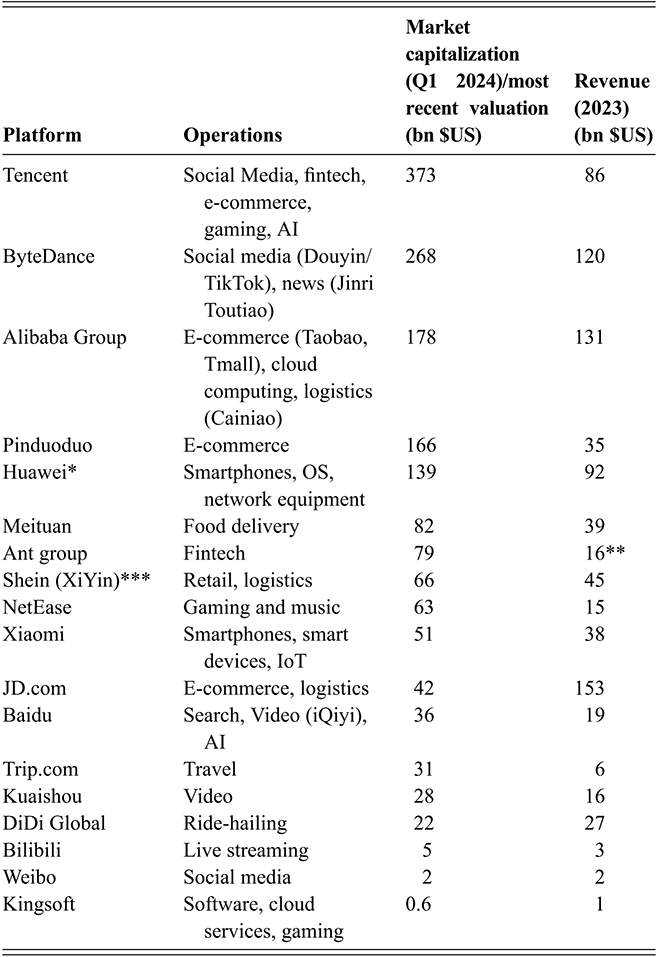

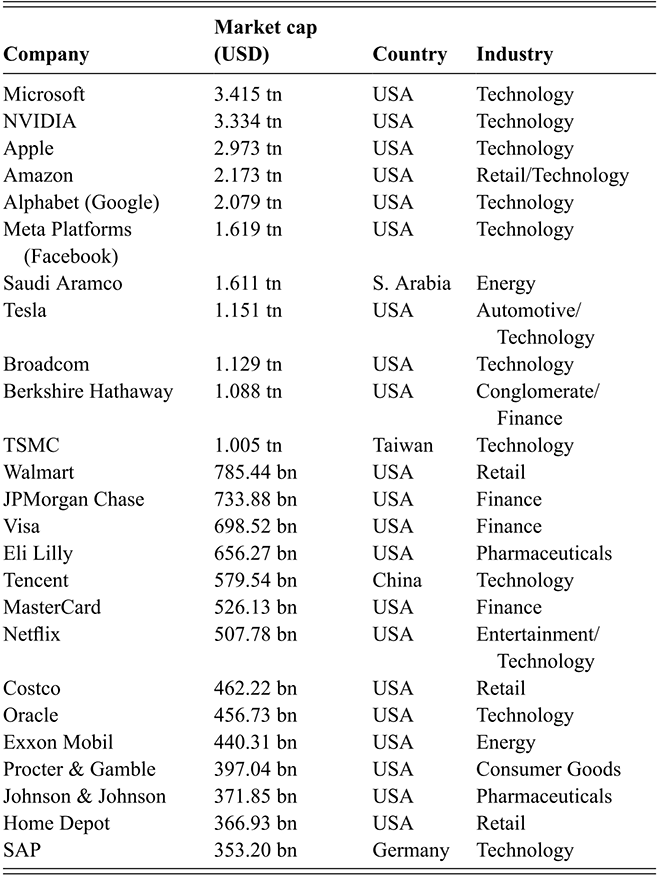

But despite what seems to be their growing global dominance, US tech giants do face mounting competition. The threat of regulation by foreign governments – so far held largely at bay by Washington – looms large (Bradford, Reference Bradford2023). But more strikingly, they confront mounting commercial competition from the country which contains their only serious rivals: China. Beijing inhibited the operations of Silicon Valley tech giants in China throughout the 2000s. As they amassed nearly unassailable market positions in many countries, they largely struggled to gain a foothold in China. This left space for domestic Chinese firms to grow and innovate. Although still considerably smaller in scale and value, today, China’s platform giants are increasingly venturing overseas and competing directly with their US rivals. In some market sectors Chinese platforms like Huawei, Tiktok, Shein, Alibaba, and ZTE can win. Huawei has no US rival in the field of 5/6 G networking and is mounting a real challenge to US opponents in the chip and AI sector, while Chinese media platform TikTok is stealing a march on American rivals across large parts of the world. Alibaba and Tencent are increasingly important players in cloud computing, while these and other firms offer a growing range of vital services to global markets such as e-government technologies, smart cities, health tech, and AI.

US institutions have voiced mounting alarm at the rapid growth of Chinese platform firms. For instance, China’s Belt and Road Initiative has facilitated the expansion of China’s global port investments. Chinese-owned ports typically deploy a logistics management platform called LOGINK that intermediates relations among shippers, receivers, port operators, and regulators. By integrating and sharing shipping data amongst these users, LOGINK provides essential functions that underpin global trade. It also writes the rules by which its users interact, which affords it significant power in trade and production networks. The US government interprets integration of this digital software with port infrastructure as a threat because ‘China’s government may use insights gleaned from LOGINK to expand and more precisely target its use of economic coercion. Data aggregated through the platform may enable China to block or disrupt trade flows’ to its enemies’ (USCC Staff, 2022). Importantly, the US government does not allege that China has actually done any of these things, but it fears widespread use of the LOGINK platform gives Beijing a strategic network position that has the potential to be weaponized.

1.4 An Emergent Global Regime of Competition

As the LOGINK example indicates, platforms do far more than intermediate relations among buyers and sellers. They also regulate and govern interactions between third parties, and extract an extraordinary amount of valuable data in the process. This expansive power to govern through code has led many commentators to understand large platform firms as alternative power centres to nation-states. According to some, firms like Google are simply too expansive and complex for states to regulate, while their rules and investment strategies continue to disrupt and reshape growing swathes of the real economy (Gu, Reference Hongfei2023).

This points to an apparent tension between the emergence of a new state capitalism and the platformization of the global economy. On the one hand, states are reasserting their role as regulators and direct economic actors worldwide. But on the other hand, the world’s largest private platform corporations exercise control over the digital infrastructure upon which states’ power – and society at large – increasingly depends. By intermediating and governing relations, platforms ‘enclose markets’ within their boundaries in ways which appears to pose a threat to states’ political prerogative (Staab, Reference Staab2024). How might we reconcile this purported rise of a new state capitalism with the simultaneous and unprecedented rise in private corporate power?

Our core contention is that far from representing a contradiction, a confluence of interest between states and platforms has emerged. In the context of growing geopolitical hostilities, the United States and China increasingly instrumentalize platforms because their ability to enclose markets and exert regulatory power afford novel opportunities to exercise power. Meanwhile, platform firms’ ambition to expand their digital ecosystems and internationalize operations has become dependent upon states. Governments act as patrons that shield platform firms from regulatory measures in foreign jurisdictions, provide direct subsidies and other preferential forms of treatment, and are the source of lucrative contracts which fund innovation and investment. This is not to deny the tensions, sometimes significant, between digital platform firms and their home states. Nevertheless, we contend that these conflicts are closer to footnotes than headlines in the story we present – states increasingly attempt to secure the global power of ‘their’ digital platforms as a means to exercizing extraterritorial forms of power, while platform firms welcome sustained support from states to bolster and secure their international operations.

This symbiotic relationship between states and platform firms, in the context of growing geopolitical rivalry, animates the emergence of a new kind of global political economic competition. We introduce the concept of state platform capitalism (SPC) to identify and theorize this novel and emergent regime of competition: in which platform firms and states cooperate in their mutual attempts to achieve control over – and weaponize if necessary – the hardware and software that underpin exchanges within the global economy (Rolf and Schindler, Reference Rolf and Schindler2023).

Clearly, not all states are equal in this global rivalry. Indeed, the two global centres of state platform capitalism today are the United States and China. This Element is about how their drive to platformize the world’s data flows has spilled over into a structure of global competition, with states and platform firms playing distinct but complementary roles in this contest for supremacy. Platform competition looks quite different from traditional capitalist competition – it encompasses conflicts between ecosystems rather than conflicts for market share in particular product lines (Cennamo, Reference Cennamo2021). Thus, state platform capitalist competition is fought out in ways and in spheres quite different from older forms of market or geopolitical competition. Our purpose here is to identify how SPC competition operates, and with what consequences.

This text is divided into two sections. The first section conceptualizes state platform capitalism and charts its rise. After presenting a historically informed theoretical framework in Section 1, Sections 2 and 3 examine, respectively, the US and Chinese varieties of SPC. We explain how these national varieties of SPC emerged, identify their key actors, and describe their organizational features and dynamics. We demonstrate how in both cases varied forms of state-firm interaction are increasingly oriented towards expanding the international reach of platforms, while simultaneously bolstering the geostrategic objectives of states. In this way, while acknowledging its distinct national manifestations, we emphasize the systemic character of SPC – and especially how its ‘varieties’ are conditioned by their interaction and competition. The second section explores how SPC animates distinctive forms of competition in a range of fields. Section 4 explores its implications for battles over digital currencies, while Section 5 reviews the competition to control future ‘smart cities’. Section 6 narrates the competition to establish digital standards (both formal and de facto), and Section 7 focuses on cybersecurity. We conclude by reflecting on the implications of SPC for the future of digital connectivity and the global political economy more generally.

Part I A New Paradigm

2 State Platform Capitalism: Theory and History

2.1 Introduction

Amidst the global health emergency and socio-economic turmoil unleashed by the COVID-19 pandemic, observers could have been forgiven for missing a conspicuous datapoint. In 2020, the ratio of US government federal spending to GDP reached an all-time high, surpassing even that achieved at the height of mobilization for total war in 1944–5 (IMF, 2024). The interventions required to prop up economies during the pandemic lockdowns were not a complete aberration; however. government spending across advanced economies has been on a steady (though fluctuating) upward trajectory ever since the end of the Second World War. The 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic simply accelerated this trend. Along with the perpetually rising economic profile of states, state capitalist practices and policy interventions have both made a dramatic return and evolved in new ways. From the expansion of sovereign wealth funds and policy banks to proliferating industrial and technology policies, and full-blown economic nationalism, state interventions in the economy have proliferated on a global scale (Alami and Dixon, Reference Alami and Dixon2024).

The re-emergence of state capitalism has coincided with an epochal shift in the organization of capitalist firms: the rise of digital platform companies to the commanding heights of the global economy. Tech firms’ boosters welcome a ‘second machine age’ of ‘brilliant technologies’ which promise dramatic increases in productivity and wealth (Brynjolfsson and McAfee, Reference Brynjolfsson and McAfee2014). Meanwhile critics argue that big tech amounts to extractive, parasitic organizations driving economies towards ‘techno-feudalism’, in which predatory tech elites extract labour from digital serfs amidst economic stagnation (Durand, Reference Durand2020; Varoufakis, Reference Varoufakis2024). Amidst this debate, there is broad consensus that digital platform firms have increasingly come to exercise ‘state-like’ governance functions that erode the power of public authorities (Lehdonvirta, Reference Lehdonvirta2022; Törnberg, Reference Törnberg2023). As platforms continue to expand, governments are understood to be waging a zero-sum ‘global battle to regulate technology’ – one which they are commonly understood to be losing (Bradford, Reference Bradford2023).

State capitalism and platform capitalism, then, appear to represent deeply contradictory trends. On one hand, states’ role as economic actors continues to multiply and intensify. Yet on the other hand, states seem powerless to regulate the largest platform firms such as Google, Amazon, and Alibaba. Which is it? And which side will win out? We present an alternative view. We show how contemporary state capitalist and platform capitalist practices – while initially distinctive and relatively autonomous trends – share deep historical roots, were both significantly driven by the global economic crises of 2008 and 2020, and are mutually reinforcing rather than contradictory trends.

Our starting point is to claim that state capitalism and platform capitalism should be conceived in the first instance as organizational and institutional ‘fixes’ to the structural problems encountered by global capitalism (Peck and Tickell, Reference Peck, Tickell and Amin1994; Alami and Dixon, Reference Alami and Dixon2020a). The concept of a fix was first developed by Harvey (Reference Harvey1981) in order to identify how capitalists and state managers devise temporary solutions to the structural crisis tendencies that frequently disrupt capitalist accumulation. They may engineer moves of money from manufacturing into real estate and infrastructure or into underdeveloped regions or economies (spatial fix), restructure businesses, outsource and offshore activities (organizational fix), or restructure policy environments to secure new avenues for growth (institutional fix). However, rather than resolving crises, fixes tend to defer, displace or redirect them. As such, fixes forestall crises, but they create novel contradictions that ultimately culminate in new crises: such is the crisis-prone nature of capitalism.

This section first identifies how a rejuvenation of state capitalist practices was significantly driven by the dynamics of a global economic slowdown in 2008, before becoming imbricated with geopolitical competition. The urgency of rescuing banking sectors and industrial producers both forced states to break with (self-imposed) laissez-faire of the globalization years, but also revealed what had always been true: that capitalist economies are underpinned by state power. But state capitalist dynamics became increasingly (geo)politicized due to the uneven and combined dynamics at play in the global political economy (Alami and Dixon, Reference Alami and Dixon2021). As some states pursue these practices somewhat successfully, others are driven to imitate and adapt to keep up. In this way, policy instruments which emerged as crisis-management tools are becoming deployed for geopolitical ends, with the effect of legitimating their use and strengthening the aspirations of other states to exert control over their own economies.

Next, we turn to the rise of digital capitalism and the platform business model. Although digitalization has a long history, the rise of giant digital platforms to pre-eminence in the global economy is equally tied up with the crisis of 2008 (Srnicek, Reference Srnicek2017). We map the evolution of platform business strategies within this broader political economy context. Finally, we demonstrate that rather than being fundamentally opposing trends, state capitalism and platform capitalism are complementary, and increasingly dovetail with one another. As governments embrace state capitalism in their attempts to bolster national security, it is only logical that they seek to exploit the tremendous governance capabilities and extraterritorial reach of platform firms. Platforms, meanwhile, seek to bolster their international scale and scope by obtaining state protection and patronage. The fusion of the distinct but convergent logics of state and platform capitalism is, we claim, fuelling a novel mode of competition between the United States and Chinese states and their platform firms, which we elaborate in the remainder of the text. As with all such ‘fixes’, however, dynamic contradictions and tensions are built-in to this mode of competition – and how these manifest is the major focus of the second part of the Element.

2.2 State Capitalism

State capitalism has a long history. The concept first was introduced with reference to concentrated industrial trusts which were increasingly tied up with the state, alongside emergent forms of national ownership, in late nineteenth-century Europe (Sperber, Reference Sperber2019). Since then, it has passed through many permutations, being used (variously) to signify diverse organizational systems: from the Soviet Union’s centralized planning apparatus and the Keynesian policy frameworks of the advanced economies during the post-war period, to the ‘illiberal’, state-directed and resource-based economies of contemporary Russia, Iran, and Venezuela (Kurlantzick, Reference Kurlantzick2016).

In this Element, we seek conceptual clarity by drawing on advances made by the literature on the ‘new state capitalism’ (Alami and Dixon, Reference Alami and Dixon2024). Much writing broadly conceived of the neoliberal period as a ‘retreat of the state’ from governing the economy (Konings, Reference Konings2010). This conceptualization understood economies to existent on a spectrum between ‘liberal’ and ‘coordinated’ market economies – with commentators treating those not fitting the ideal types as state capitalist aberrations, limited to a handful of middle-income and developing economies like Russia, Turkey, and China (e.g., Bremmer, Reference Bremmer2009). Such work ignored the considerable support (both financial and in terms of coordination) states offered to their firms right through the neoliberal period (Alami and Dixon, Reference Alami and Dixon2020b). It also offered a poor means by which to grasp how or why a dramatic expansion of highly visible and direct statist interventions have proliferated on a global scale – across virtually all varieties of capitalist economy.

By contrast, following Alami and Dixon (Reference Alami and Dixon2024), we conceptualize state capitalism not as an ideal type or a variety of capitalism, but as a set of processes and relationships by which states seek to actively support the process of capital accumulation. Understood in this way, state capitalism is conceived as a perennial feature of real capitalist economies – but also that as a set of practices, it is potentially subject to transformation, evolution, and increases (or decreases) in scale and scope over time. There is indeed both continuity and innovation in contemporary state capitalist practices (Musacchio et al., Reference Musacchio, Lazzarini and Aguilera2015). They range from what Alami and Dixon (Reference Alami and Dixon2021, 765) identify as ‘state-capital hybrids’ like sovereign wealth firms, state-owned (or backed) firms and policy banks; to the ‘muscular statism’ of industrial and innovation policies, capital controls, and development and planning strategies. And while many interventions are underpinned by economic nationalism, the new state capitalism is simultaneously transnational in character. Far from acting in ways which fragment the globalized economy, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are major drivers of transnational economic integration as they pursue expansive overseas investments (Babić et al., Reference Babić, Dixon and Liu2022).

Understood in this way, it is clear that state capitalist practices have dramatically increased in both scale and scope over the past decade and a half. What drove the emergence of the new state capitalism? The global financial crisis of 2008 punctured deep-seated assumptions about the smooth evolution of neoliberal globalization. It generated far-reaching changes in the structures and dynamics of the world economy, most notably inaugurating a period of secular stagnation in growth and productivity. While these trends predate 2008 (Brenner, Reference Brenner2006), both were considerably worsened by the economic crisis and its aftermath. The economic turmoil initiated by lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic also simply served to accelerate these long-standing economic trends as states struggled to contain the economic fallout (van Apeldoorn and de Graaff, Reference van Apeldoorn and de Graaff2022). It was fundamentally the deepening of economic stagnation, punctuated by the economic crises of 2008 and 2020, which drove states to intervene in their economies in ever more intensive ways to support growth.

The effect of rising state capitalist interventions was often to stabilize or even boost growth for its practitioner economies. But at the same time, state capitalist practices have inevitably served to fragment the global economy. The IMF has warned of rising ‘geoeconomic fragmentation’ as states seek to exert control over their economies (Gopinath, Reference Gopinath2024). International business scholars have identified how state capitalist practices have solidified the emergence of poles of political-economic power characterized by increasingly distinct regional market structures, supply opportunities, regulatory systems, and risk environments (Luo and Van Assche, Reference Luo and Van Assche2023; Lewin, Reference Lewin2024; Luo and Tung, Reference Luo and Tung2025). At the same time, states seek to exert greater control over global value chains which extend far beyond their national or regional territories, driving ongoing integration and tension between economic poles (Schindler and Rolf, Reference Schindler and Rolf2024). These new state capitalist practices are the source of considerable geopolitical tensions, as they threaten to disrupt the relatively unified and open global economy which was forged during the neoliberal period (Alami et al., Reference Alami, DiCarlo, Rolf and Schindler2025). Indeed, statecraft is increasingly geared towards securing the conditions for long-term economic security and competitiveness, industrial and technological leadership, and resilience of critical supply chains and production networks (Weiss and Thurbon, Reference Weiss and Thurbon2020; Weiss, Reference Weiss2021). In this way, contemporary statist economic practices can be seen simultaneously as responses to and drivers of geopolitical tension.

Despite proliferating regional conflicts, the US-China rivalry represents the key geopolitical driver of this resurgence in state capitalist practices. Since the rapprochement between China and the United States during the later stages of the Cold War, US policy towards China remained largely consistent for three decades. Its principal focus was on pushing China to open its markets and financial sector to US and global investors, in exchange for receiving access to US markets and facilitating its entry into the global economy (especially via joining the WTO) (Rolf, Reference Rolf2021; Hung, Reference Hung2022). Despite acceding to the WTO in 2001, China implemented neoliberal reforms only selectively, trimming but never dismantling its powerful state sector. At the same time, Beijing ramped up its spending on military capabilities in line with growth, as military spending became a key part of China’s broader innovation ecosystem (Cheung, Reference Cheung2022). Pockets of support for pursuing more hardline neoliberal reform were fatally undermined by the global financial crisis of 2008, in the aftermath of which officials doubled down on ‘state capitalist’ practices. These included large-scale stimulus packages concentrating on infrastructure building, the launching of an expansive and expensive industrial policy in 2015 called Made in China 2025 (Naughton and Tsai, Reference Naughton and Tsai2015), and subsequently ploughing unprecedented quantities of funding towards strategic private sector fields like ICT and green technology (Naughton, Reference Naughton2020b).

The United States enacted a major foreign policy ‘pivot to Asia’ in 2011, explained at the time by US foreign policy elites as a response to China’s mooted ‘new assertiveness’ (Shambaugh, Reference Shambaugh and Shambaugh2020). In addition to re-asserting power in the Asia Pacific after a decade of war in the Middle East, this pivot was driven by a desire to prevent China from becoming a new centre of political-economic gravity in the global system (Turner and Parmar, Reference Turner and Parmar2020). Critically, the United States developed a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, designed to freeze China out of regional trade and technology networks, though the agreement ultimately floundered during 2016 (Ravenhill, Reference Ravenhill2017).

The US pivot and TPP sat uneasily alongside the Obama administration’s purported commitment to a ‘liberal peace’ power politics, and to ongoing engagement with China (Harris and Trubowitz, Reference Harris and Trubowitz2021). The Trump administration, by contrast, abandoned this long-standing ‘Open Door’ geopolitics (van Apeldoorn et al., Reference van Apeldoorn, Veselinovič and de Graaff2023) in favour of a bluntly mercantilist trade policy. Initially, the objective was to reduce the US trade deficit with China by imposing a series of tariffs, but the mission quickly expanded to include targeting China’s leading high-tech firms such as Huawei and ZTE. This profound and long-standing foreign policy shift was outlined in the 2017 US National Security Strategy. Not only did it identify China (alongside Russia) as the primary threat to national security (rather than non-state terrorist groups), but it rejected the notion that they could become partners through diplomatic engagement and economic integration:

These competitions require the United States to rethink the policies of the past two decades – policies based on the assumption that engagement with rivals and their inclusion in international institutions and global commerce would turn them into benign actors and trustworthy partners. For the most part, this premise turned out to be false.

While Trump did reach a temporary trade accord with Xi Jinping’s administration, the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted its implementation and relations collapsed. The Biden administration essentially embraced the Trumpian worldview, systematizing Trump’s piecemeal initiatives into an increasingly comprehensive framework aimed at limiting China’s integration with the global economic order, and maintaining US dominance in strategic high-technology sectors (Leoni, Reference Leoni2022). Trump’s return in 2025 simply signalled the death knell for any hope of a reversion in US policy.

The scope for a reduction in geopolitical tension appears limited. Both the United States and China have deployed expansive state capitalist practices towards the rivalry, in ways which have permanently reconfigured the dynamics of their economies. China’s party-state has deepened its reach across its economy, by expanding the influence of SOEs and in deepening control mechanisms over the private sector (Liu and Tsai, Reference Liu and Tsai2021; Pearson et al., Reference Margaret, Rithmire and Tsai2021). Meanwhile, the United States has moved in a similar direction, albeit within ideological constraints imposed by its political system. Starrs and Germann (Reference Starrs and Germann2021) observe sweeping changes in (1) the US tariff regime, designed to target Chinese imports in particular; (2) the inward investment regime, aimed at restricting Chinese firms’ access to high-tech US companies; and (3) export regulations, which use technology export bans to target Chinese firms like ZTE and Huawei. Heightened local procurement requirements have also been enacted through the reformed implementation of the Buy American Act, alongside evidence for a growing consensus on the value of state-led investments in strategic technology development and mission-oriented development projects in areas such as supply-chain reshoring and 5 G provision (Baltz, Reference Baltz2022).

But despite recent ructions caused by the second Trump administration’s imposition of tariffs, the costs of full economic decoupling between the US and China seem to remain prohibitive (Rosen and Gloudeman, Reference Rosen and Gloudeman2021) – both for the economies themselves, and for third countries. The ‘new state capitalism’, far from autarchic, is instead substantially geared towards the establishment of control over the transnational networks that constitute the architecture of globalization (Schindler et al., Reference Schindler, Alami and DiCarlo2023). China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), for instance, has extended China’s reach across Eurasia, Africa, and Latin America through a sweeping range of state-backed infrastructural investment and development financing initiatives. The BRI has in turn prompted the entry of the US government directly into the infrastructure financing space with its Development Finance Corporation and the nascent US-led G7 ‘Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment’ (PGII). So far, it these initiatives are much smaller than the BRI, and they have also failed to meet their modest objectives (Schindler and Kanai, Reference Schindler and Kanai2021; Hameiri and Jones, Reference Hameiri and Jones2024). Nevertheless, this competition to coordinate the build-out of physical infrastructure is increasingly tied to a related, and equally intense, competition over digital technologies.

2.3 Platform Capitalism

[W]hat is internet infrastructure? Of course, there are data centres and massive server farms. There are devices produced by a handful of companies, and operating systems … we must also include labour and practice, content moderation, device manufacture in Shenzhen, rare earth mineral mining, etc. – all of which is infrastructure … What affordances sit below the thing we are seeing on the surface? Who owns those affordances? These are the questions we should be answering.

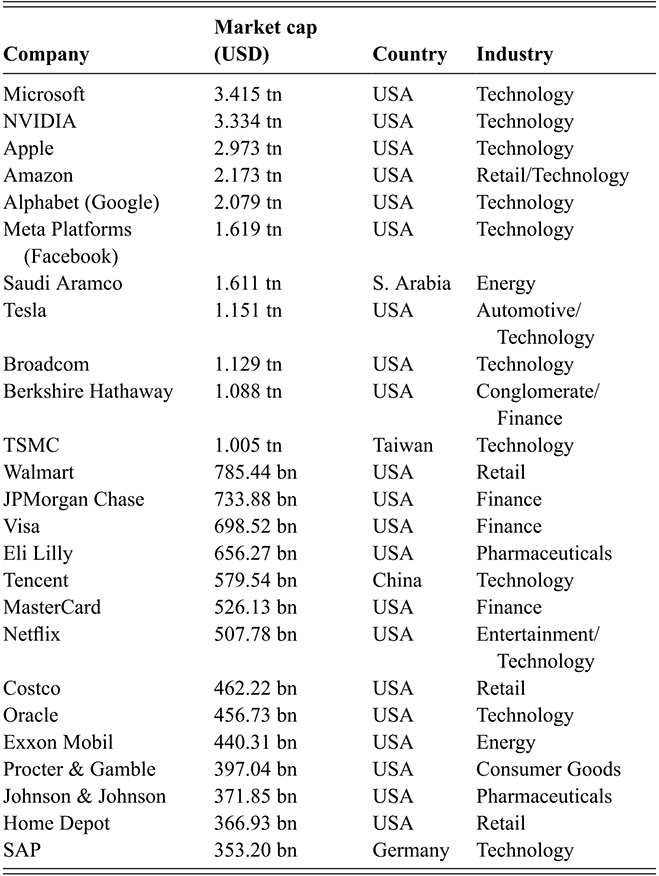

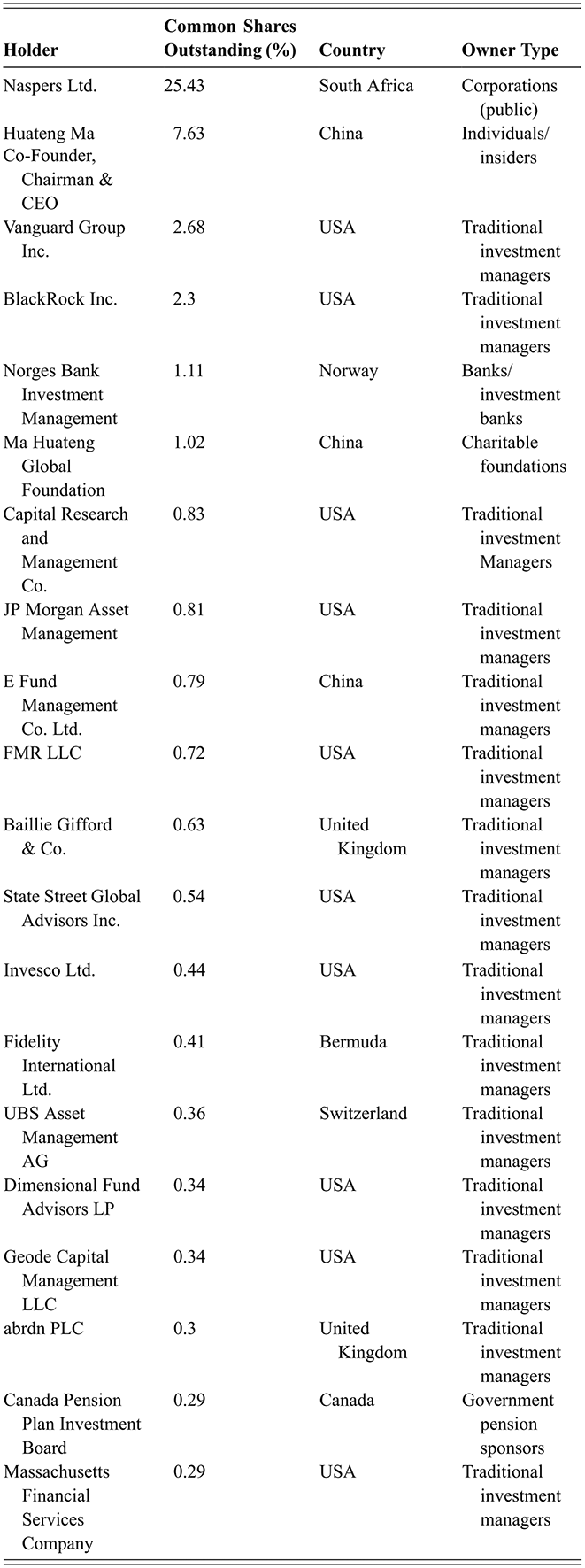

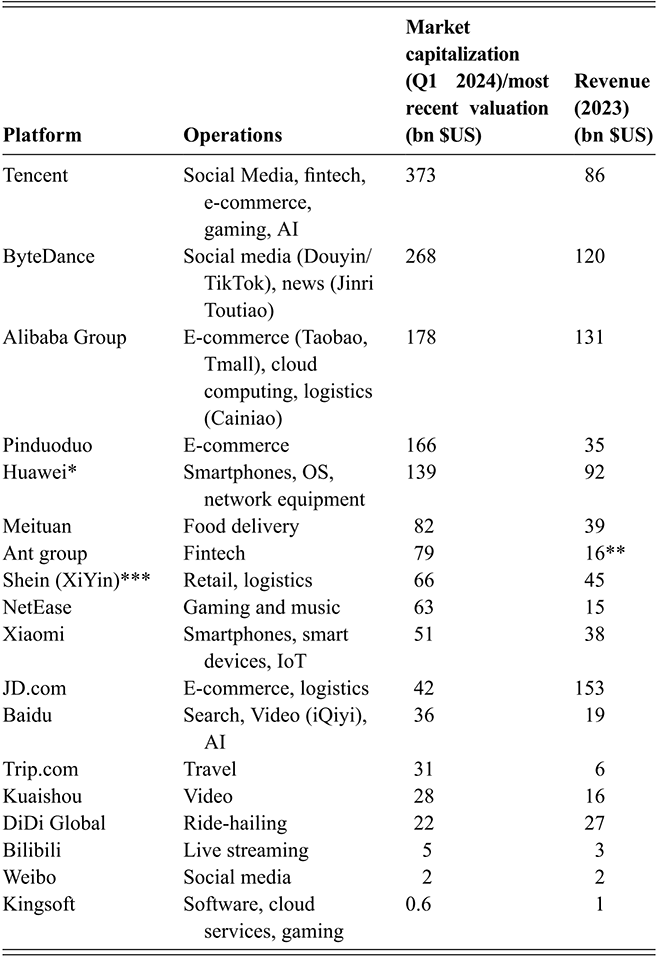

As state capitalist practices expanded during the 2010s, observers fixated on another, perhaps more dazzling, trend: the emergence of platform capitalism. More than simply the digitalization of economies and societies, platform capitalism is characterized by the astonishing ascendance of platform companies to the heights of the global economy (Table 1). Observers of Forbes’ Global 500 ranking of top corporations in 2007 would not find a technology company near its top-25 positions, which were dominated by oil producers, auto firms, and banks. But digital behemoths like Amazon, Google/Alphabet, and Apple skyrocketed to the top of such lists in the decade after 2008. As of 2025, seven of the world’s twenty-five top firms by market value are platform businesses (Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Tencent, and SAP; see Table 1). Other major hardware firms generate the bulk of their businesses by selling hardware and services to these digital giants (NVIDIA, TSMC, Broadcom, and ASML). And manufacturers of digital devices such as Samsung and Tesla employ platform business models, as does the retailer Walmart in its online marketplace.

Table 1Long description

For each company, the table provides its name, market capitalization, home country, and primary industry sector. The data is sourced from companiesmarketcap.com.

The list is as follows:

1.Microsoft: U S D 3.415 trillion, U S A, Technology

2.NVIDIA: U S D 3.334 trillion, U S A, Technology

3.Apple: U S D 2.973 trillion, U S A, Technology

4.Amazon: U S D 2.173 trillion, U S A, Retail/Technology

5.Alphabet (Google): U S D 2.079 trillion, U S A, Technology

6.Meta Platforms (Facebook): U S D 1.619 trillion, U S A, Technology

7.Saudi Aramco: U S D 1.611 trillion, Saudi Arabia, Energy

8.Tesla: U S D 1.151 trillion, U S A, Automotive/Technology

9.Broadcom: U S D 1.129 trillion, U S A, Technology

10.Berkshire Hathaway: U S D 1.088 trillion, U S A, Conglomerate/Finance

11.TSMC: U S D 1.005 trillion, Taiwan, Technology

12.Walmart: U S D 785.44 billion, U S A, Retail

13.JPMorgan Chase: U S D 733.88 billion, U S A, Finance

14.Visa: U S D 698.52 billion, U S A, Finance

15.Eli Lilly: U S D 656.27 billion, U S A, Pharmaceuticals

16.Tencent: U S D 579.54 billion, China, Technology

17.MasterCard: U S D 526.13 billion, U S A, Finance

18.Netflix: U S D 507.78 billion, U S A, Entertainment/Technology

19.Costco: U S D 462.22 billion, U S A, Retail

20.Oracle: U S D 456.73 billion, U S A, Technology

21.Exxon Mobil: U S D 440.31 billion, U S A, Energy

22.Procter & Gamble: U S D 397.04 billion, U S A, Consumer Goods

23.Johnson & Johnson: U S D 371.85 billion, U S A, Pharmaceuticals

24.Home Depot: U S D 366.93 billion, U S A, Retail

25.SAP: U S D 353.20 billion, Germany, Technology

The list is dominated by US-based technology companies, which occupy 12 of the top 25 positions.

Platforms, many of which predate the global economic crisis, grew rapidly in the post-crisis era. This is in large part because they offer a business strategy suited to a world of slow growth and low interest rates (Srnicek, Reference Srnicek2017; Davis, Reference Davis2022). Platforms’ business strategies can in this way be understood as an ‘organizational fix’ to the challenge posed by secular stagnation of economies. In the 2010s, Western financial sectors were flush with cash thanks to quantitative easing, bond purchasing programmes, and other mechanisms put in place to prop up the financial sector. Of the estimated $35 trillion in credit created by central banks between 2009 and 2022, Varoufakis (Reference Varoufakis2024) estimates that a large majority of the share invested in productive assets found its way into the platform economy. This took place via myriad mechanisms, including saturated corporate bond markets, which themselves generated soaring stock markets as investors became prepared to pay a premium for tech equity; a generalized inflation in asset prices; and a flood of private equity and venture capital into technology startups (which could be acquired, or have their innovations acquired, by hyperscalers) (Kenney and Zysman, Reference Kenney and Zysman2019; Rikap, Reference Rikap2024).

Rather than deploying this capital towards traditional competition in (saturated) global markets by offering specific goods and services, platform firms instead aim to build business ecosystems in which their infrastructure intermediates exchanges between external users, developers, and (sometimes) advertisers (Kenney and Zysman, Reference Kenney and Zysman2016). This requires typically very considerable investments in both tangibles and intangibles, R&D, and outlays on user recruitment (Klinge et al., Reference Klinge, Hendrikse, Fernandez and Adriaans2023). Because platforms’ services are substantially intangible, their low marginal cost affords opportunities to achieve scale and scope economies at breakneck speed, supported by the use of cloud computing (Narayan, Reference Narayan2022). Once critical scale has been achieved, the switching costs imposed by network effects serve as a powerful way of locking-in user bases. Margins on transactions are often tiny, but low margins can be offset with extremely high volume. And platforms operate across multiple horizontal business lines, using cross-subsidization to build attractive multi-service ecosystems (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Ritala, Karhu and Heiskala2024). Given their privileged access to financial markets, profitability is often less of an imperative (at least in the short term) for platform firms than their ability to scale. According to one estimate, platform firms will soon come to mediate one-third of all global economic activity (Dietz et al., Reference Dietz, Khan and Rab2020).

Broadly speaking, the open architecture of a platform constitutes a core-periphery model, in which core technologies are under the direct control of the platform firm, while third-party designers generate complementary innovations (Rodon Modol and Eaton, Reference Modol, Joan and Eaton2021). External developers’ (complementors) innovations further enhance network and lock-in effects. The Apple Store, for instance, relies on third-party companies to build the majority of iOS apps which make the iPhone a useful and attractive device. But because platform firms maintain ownership of and control over their cores, they retain the authority and capacity to rewrite the rules (protocols) through which ecosystem users interact (Galloway, Reference Galloway2004). A core goal of platform protocol is to prevent so-called ‘multihoming’ and deepen user lock-in via technical means. Consequently, in certain sectors platform firms have become unavoidable intermediaries, mediating the exchange of goods and services amongst users within enclosed digital spaces (Langley and Leyshon, Reference Langley and Leyshon2017).

As a function of being unavoidable intermediaries in transactions and exchanges, platform firms are able to leverage control over protocol to influence everyday habits and practices (Grön et al., Reference Grön, Chen and Ruckenstein2023). Locking users into ecosystems enables platforms to extract payment from value circulating across platform networks (Sadowski, Reference Sadowski2020; Arboleda and Purcell, Reference Arboleda and Purcell2021), but also to write the rules by which they interact. Staab (Reference Staab2024) consequently argues platforms represent the rise of privatized marketplaces. Innovations like algorithmically generated prices and supplier rankings systems disrupt market pricing mechanisms to the extent that the integrity of public markets – the cornerstone of capitalist economies – is potentially threatened. Furthermore, platforms’ control over protocol also affords them enormous power to reshape the business processes of firms which use their infrastructure (Nowak et al., Reference Nowak, Rolf and Wei2022). Consider, for instance, the ability of Apple to exert control over third-party apps in its App Store via terms of service.

Platform power is predicated upon the capability to integrate technology ‘stacks’: assemblages of global-scale computational hardware and software. Digital platforms constitute a user-friendly interface for efficiently navigating this subterranean ‘infrastructural complex of server farms, massive databases, energy sources, optical cables, wireless transmission media, and distributed applications’ (Bratton, Reference Bratton2016, 70). While this assemblage of devices and software is intrinsically open (‘the open web’), platforms seek to wall off access to sections of these stacks using technical barriers, IP law, restricted access to APIs, and algorithmic filtering and curation. They monopolize the ‘walled gardens’ they create in a way that was impossible with the open internet (Plantin and De Seta, Reference Plantin, Seta and Gabriele2019; Peck and Phillips, Reference Peck and Phillips2021). In this way, platform competition is distinct from typical competition in lines for specific products or services. For Jacobides (Reference Jacobides2019), ‘in a growing number of sectors, the firm and even the industry have ceased to be meaningful units of strategic analysis. We must focus instead on competition between digitally-enabled designed ecosystems that span traditional industry boundaries and offer complex and customisable product-service bundles’.

Like earlier vertically integrated corporations, platforms aim to minimize transaction costs and exercise market dominance. Yet, they differ markedly in some ways. Rather than employing vertical integrated command structures (Chandler Jr, Reference Chandler1977), they instead operate by organizing market interactions digitally, and exerting control through ecosystem governance via ‘terms of service’ commands rather than managerial hierarchies. The power to orchestrate and govern without owning represents a powerful evolution of corporate control strategies (Grabher, Reference Grabher2025).

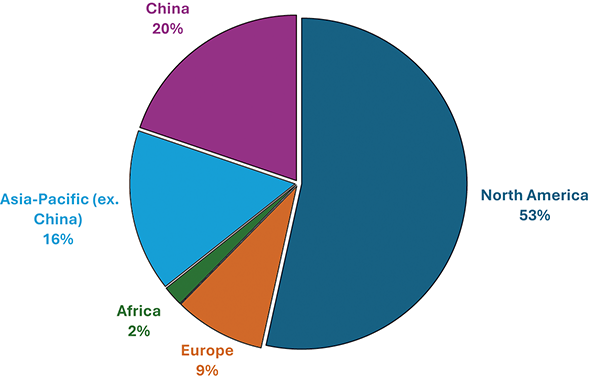

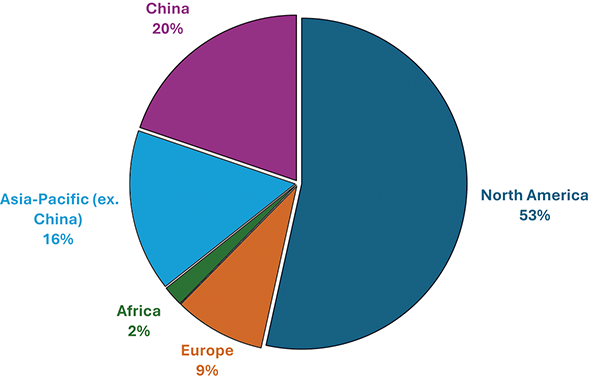

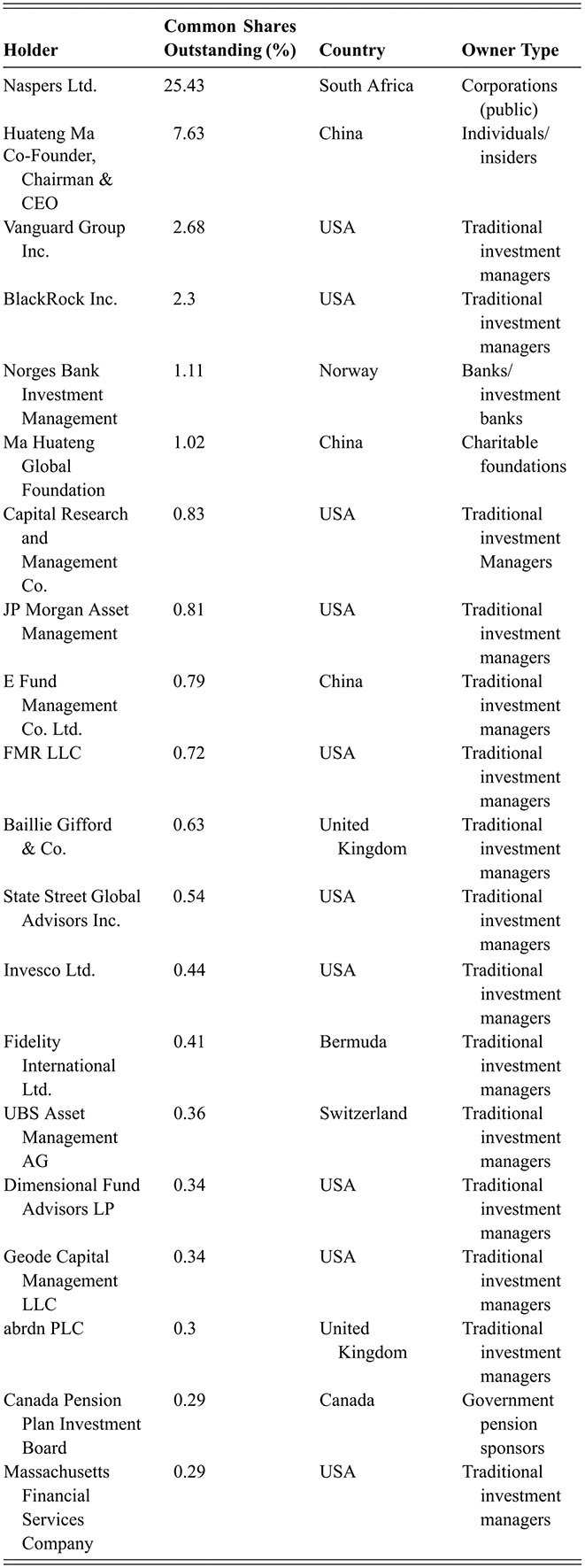

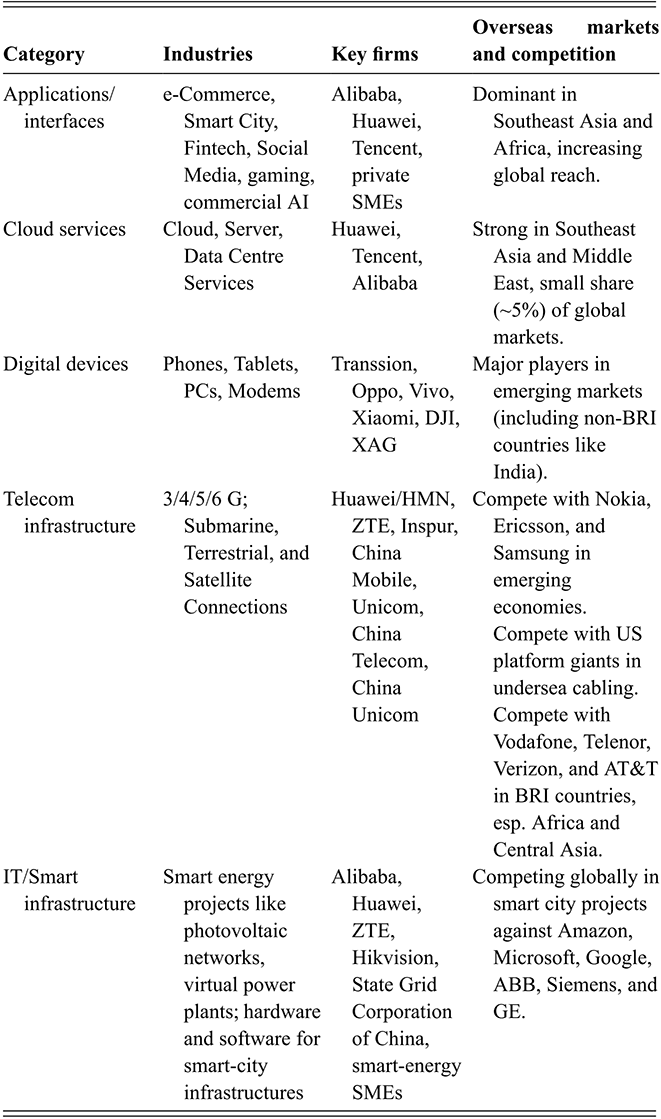

The extreme corporate concentration and financial dominance of giant platform firms is represented by a distinctive economic geography with two main poles (Kenney and Zysman, Reference Kenney and Zysman2020). The United States dominates, with the combined value of the so-called ‘magnificent seven’ technology firms (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Tesla) representing about a third of US stock market value as of May 2025. China represents another pole of digital power in the global political economy (Figure 1). The platforms domiciled in both these countries have immense extraterritorial power, given they exercise considerable control over most of the world’s technology stacks (Mayer and Lu, Reference Mayer and Yen-Chi2025)

Figure 1 Top 101 global platform firms by region/country of domicile, 2023.

2.4 State Platform Capitalism

Rather than cutting against one another, the distinct logics of state and platform capitalism have coalesced in unanticipated and generative ways. The specific political-economic affordances that characterize the platform business model are increasingly recognized as a vital source of power by states. As such, rather than simply trying to curtail platforms’ growth, states seek to govern through platforms: to instrumentalize and mobilize them in pursuit of geostrategic objectives. At the same time, in a world characterized by competition and growing calls for platform regulation, home state backing is becoming indispensable for US and Chinese platform firms to maintain and expand the dominance of their digital ecosystems in the global political economy. It is this increasingly symbiotic relationship between states and platform firms that we refer to as state platform capitalism (SPC).

We conceptualize SPC as the collaborative and reinforcing individual efforts of states and platform firms – principally in the United States and China – to compete to establish and maintain control over the technology stacks that serve as the underlying infrastructure of globalization. The power exercised by digital platforms derives from their technical and corporate control over the computational infrastructures and business ecosystems upon which a growing share of global economic activity depends. For states, platforms represent potential ‘points of infrastructural control [which] can serve as proxies to regain (or gain) control or manipulate the flow of money, information, and the marketplace of ideas in the digital sphere’ (Musiani et al., Reference Francesca, Cogburn, DeNardis and Levinson2016, 4). Control over the technology stacks and socio-economic exchanges which platforms orchestrate is central the competitive dynamics of SPC. Given the ongoing expansion of states’ definitions of ‘national security’ and the geopolitical competition for network centrality, it is unsurprising that platforms have become central to great power rivalry between the United States and China (Gray, Reference Gray2021; Shen and He, Reference Shen, Yujia, Qiu, Yu and Oreglia2022).

Most major digital platform firms are domiciled in either the United States or China, and both states are deploying a barrage of state capitalist practices to establish control over digital platforms and enlist them in pursuit of geostrategic objectives. Three distinctive competition dynamics result, which we outline here in turn as: infrastructural platform geopolitics, digital dependencies, and cross-stack rivalry.

Infrastructural platform geopolitics has emerged as states have come to recognize the extraterritorial power potentials of transnational infrastructures (Westermeier, Reference Westermeier2020; Abels and Bieling, Reference Abels and Bieling2024), while platforms have increasing taken on infrastructural properties (Plantin et al., Reference Plantin, Lagoze, Edwards and Sandvig2018; Shen, Reference Shen2022a). Some platform firms can be directly weaponized (Farrell and Newman, Reference Farrell and Newman2023) by their host states in nakedly geopolitical ways. For instance, WikiLeaks was famously denied vital services by internet platforms such as Amazon Web Services, and EveryDNS at the behest of US government pressure (Tusikov, Reference Tusikov, Drezner, Farrell and Newman2021), while the second Trump administration has ordered a ban on access to US chip design platforms for Chinese firms. However, for the time being, such weaponization remains the exception rather than the norm, and this tremendous power to deny adversaries access to (or otherwise weaponize) platforms remains latent. Indeed, excessive weaponization initiatives are likely to reduce the appeal of platforms and induce users to switch to other platforms despite the cost. Instead, platforms’ infrastructural power derives from how they entrench power relations by monopolizing key passage points, while rerouting, ordering, and governing flows of data and capital in ways which potentially redound to the benefit of their home states (Westermeier, Reference Westermeier2020; Bakonyi and Darwich, Reference Bakonyi and Darwich2024; Hardaker, Reference Hardaker2025). To this end, states seek to secure favourable regulatory environments (both at home and abroad), preferential financing, and forms of strategic endorsement that enable platforms to both scale and embed themselves in technology stacks.

This leads us to the second dynamic: fostering digital dependencies. Many countries are increasingly dependent upon US and Chinese platforms since they underpin access to the global economy (Mayer and Lu, Reference Mayer and Yen-Chi2025). Maintaining this dominant position is key to the profit strategies of platform firms, and it upholds the power asymmetries between states. Through lobbying, financial support, and implanting platforms with in bilateral agreements and initiatives, states seek to render third countries’ technology stacks critically reliant upon their platform infrastructures and embed them in overseas technology stacks. At the same time, states and platforms collaborate to centralize and police access to the critical resources which sustain their dominance – including compute power (as in licensing regimes for NVIDIA accelerator chips and remote AI datacentre access) and data flows (especially for AI model training). Limiting interoperability and resisting multihoming by third countries are key targets for platforms’ home states in fostering digital dependencies.

Finally, and as discussed further in the next section, states and platforms collectively practise forms of cross-stack rivalry. Platforms compete as sprawling business ecosystems rather than price or quality of individual product lines. This can limit rivalry and competition between platforms from the same home state, giving rise to ‘frenemy’ relations or coopetition between platforms (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Urmetzer and Ansari2025). States may support the emergence of such cooperative relations in overseas markets in efforts to cohere third countries into the national technology stack of the United States or China. Platforms’ extraterritorial expansion may be supported by such a state-facilitated bundling of functions, as in shared investments in data centres, cabling systems, or other infrastructure that comprises digital stacks. Moreover, cooperative relations mean successful competition in one field (such as an overseas cloud market) is likely to redound to the benefit of platforms from the same home state.

None of this is to say that the interests of big tech platforms and home states are entirely aligned. They sometimes diverge and are subject to contestation and renegotiation. Platforms cannot be reduced to mere instruments of political power. Indeed, it is precisely because ‘platform ecosystems are not simply commercial mechanisms or state-controlled entities … [that] they are becoming more and more part of a global geopolitical contest’ (van Dijck and Lin, Reference van Dijck and Lin2022, 65). In the following sections, we inquire more deeply into the specific mechanisms which drive platforms and states to cooperate in the global competition for digital dominance.

3 The US Stack

3.1 Introduction

In 2022, Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, issued a stark warning from a podium at the Capital Hilton Hotel in Washington DC. The United States risked falling behind China in the digital technology race:

It’s possible to imagine a dark future … Imagine that everything around you, everything you see in this room, has a component of Chinese values in it … free speech being restricted, being recorded, being surveilled. While China has achieved many impressive things, I would not want to live there … The real issue here is that we screwed up. We cannot get ‘5Ged’ again. I was part of the errors 20 years ago and 30 years ago in the semiconductor sector, where we collectively thought, ‘That’s fine, that’s not that important, we can figure it out, globalization will work.’ Meanwhile, we’ve ended up in a situation where my phone doesn’t work most of the time, whereas in China, where I may or may not be allowed back into, they have roughly a billion people on track to having a gigabit to their mobile phones in urban centers within the next year or two.

Schmidt was launching his new initiative, the Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP). Explicitly modelled on Henry Kissinger’s ‘Special Studies Project’, the Rockefeller-funded bipartisan initiative which built public consent and enthusiasm for the massive military and technology investments needed to prosecute the Cold War, Schmidt’s SCSP would bring together leading industry figures and politicians to cement the consensus for public investments in digital technologies to counter the ‘China challenge’. He emphasized that the ‘unifying idea of SCSP is competition, both within the various players in our system and between countries. This competition makes us stronger, not weaker. We need to win that competition’ (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2022).

Schmidt’s close collaboration with the Biden administration came to an end with the return of Donald Trump to the White House. But the personal intimacy between big tech leaders and state managers did not. The front row of Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration at St John’s Episcopal Church in January 2025 was reserved for Google CEO Sundar Pichai, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg, Apple CEO Tim Cook, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, and Tesla CEO Elon Musk – a clear signal of the privileged access to the levers of statehood to be granted to platform leaders. This section charts the central role of platform firms in driving the US global digital technology dominance, before examining how the state and platform firms are increasingly collaborating to defend this dominance in the face of growing Chinese competition.

3.2 The US Stack

The United States is home to the world’s most dynamic technology sector, whose firms dominate all nearly all key layers of the technology stack. Chip designer NVIDIA’s market capitalization is roughly equivalent to the top-forty publicly listed German firms, while Microsoft’s exceeds the entire FTSE 100 (Nikou Asgari et al., Reference Asgari, Smith, Wilson and Douglas2024). The United States has spawned the world’s largest platforms, whose global footprint is so ubiquitous that by some accounts it constitutes a form of ‘digital colonialism’ in its relations with other countries (Kwet, Reference Kwet2019). Moreover, the US tech sector is deepening its ties with the American state (González, Reference González2024). Platform firms are central to this trend.

Leading platform firms that emerged from Silicon Valley’s high-technology ecosystem began to develop increasingly close ties with the US government during the war on terror after 2001 (Weiss, Reference Weiss2014; O’Mara, Reference O’Mara2020). Their relationship encompasses both widespread government contracting and an emphasis on public-private partnerships (PPPs) (Weiss and Thurbon, Reference Weiss and Thurbon2020). Federal institutions such as the National Science Foundation, NASA, DARPA, the SBA, and National Labs dole out substantial funding in support of research and development that is critical to the US digital economy (Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2013; Wade, Reference Wade2017; Tassinari, Reference Tassinari2018). Despite this financial support, however, US techno-industrial policy remains relatively decentralized – and rather than directly intervening and ‘picking winners’, policy is designed to steer and support innovation. Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Wood, Keller, Wright, Wood and Cuervo-Cazurra2022, 22) describe this as a ‘large, decentralized apparatus for innovation within the US federal government, in which scores of agencies, often working in a largely uncoordinated fashion, engage with private firms to promote innovative breakthroughs in a wide array of sectors’. While each of these agencies has independent priorities, an underlying but emergent strategy is increasingly discernible. The US government seeks to safeguard the dominant position of its platforms worldwide, while progressively incorporating them into the military-industrial complex, because they possess unique attributes that, when mobilized, augment long-term geostrategic objectives.

Military and national security interests consequently play an outsized role allocating funding in this uncoordinated funding environment. US capital markets continue to be the world’s largest and most liquid, accounting for around 40% of the world’s total equities (around four times that of China). Wall Street established powerful conduits in Silicon Valley VC during the 1990s and cemented the route to IPO via the NASDAQ, developing links between financial and tech capital have only grown in scope and scale since (Walker, Reference Walker2006). Smaller tech firms enjoy uniquely abundant private capital markets, while Wall Street offers vast liquidity for IPOs or buyouts. But the influence of the US national security state looms large. Schwartz (Reference Schwartz2017, 327) describes it as a ‘vast technology enterprise spanning R&D, seed funding, commercialization, and both spin-off and spin-on of new technologies’. Private capital commonly follows in the wake of big bets placed on unlisted technology firms by the Department of Defense, since receiving funding from the US national security state (or one of its financial conduits) acts as a seal of approval for investors. These dynamics explain how, as Robinson (Reference Robinson2020, 40) explains, the ‘Silicon Valley-Wall Street nexus becomes in turn interlocked with the military-industrial-security complex’.

There is a long history of cooperation between the US government and American defence contractors. Yet the increasingly intimate relationships between elites in Washington and Silicon Valley, and dense financial links between public and private entities in the tech sector, represent a qualitative shift in the way that nominally civilian firms are integrated into security procurement. The US government not only offers financial resources, but it has also expanded control over tech firms – and platform firms in particular – through state capitalist regulatory instruments that are justified by the threat posed by China (Gertz and Evers, Reference Gertz and Evers2020). For instance, the Trump administration’s national cyber strategy published in 2018 labelled China a ‘strategic competitor’, concluding that the ‘vitality of the American marketplace and American innovation’ in the tech sector is a matter of national security (The White House, 2018, 14). The strategy envisions a symbiotic relationship between the state – namely its defence-related organizations – and American tech firms. This was echoed by the DoD’s (U.S. Department of Defense, 2018, 9) Cyber Strategy, which, in short, is designed to:

defend forward, shape the day-to-day competition, and prepare for war by building a more lethal force, expanding alliances and partnerships, reforming the Department, and cultivating talent, while actively competing against and deterring our competitors. Taken together, these mutually reinforcing activities will enable the Department to compete, deter, and win in the cyberspace domain.

Platform firms have become an important pillar of national security strategy because they provide vital infrastructural and technological services which state agencies do not possess, while their R&D budgets dwarf available public resources and incumbent defence contractors. The Defense Innovation Unit reported that US platform giants outspend its top defence contractors (e.g., Lockheed Martin and Raytheon) on R&D by 11-to-1 (Brown, Reference Brown2021, 13). Google’s 2024 R&D spending amounted to $45 bn, around five times the budget of the National Science Foundation. Collaboration offers state agencies the opportunity to influence platforms’ R&D strategies, as in the National Cyber Strategy that will ‘use its purchasing power’ to shape innovation and influence firm behaviour in support of defence goals (The White House, 2018, 8). The ‘third offset’ – a military strategy aiming to leverage private sector innovations for defence purposes – became embedded in the 2018 National Defense Strategy (Gentile et al., Reference Gian, Michael and Evans2021). Ultimately the military-industrial-security complex is in the process of reworking state-business relations in the platform sector, with the objective of aligning the business strategies of the world’s largest platform firms with Washington’s geostrategic imperatives.

One objective of state financial support is to support the incorporation of platform and other high-tech firms into the defence sector. This requires more than an alignment of financial interests, and explains the growing integration between political and tech elites in Washington and Silicon Valley. For example, the Defense Innovation Board (DIB) was established in 2016, bringing together leaders from the private tech sector, venture capitalists and former military officers who advise the Department of Defense on its technology policy. Its first chair was Eric Schmidt. The DIB (Defense Innovation Board, 2024) explains:

Peer and near-peer competitors are challenging U.S. primacy across a number of domains and technologies, and DoD must navigate shifting economic and industry environments to meet these challenges and achieve mission success. In this context, the DIB provides outside independent expertise to the Department to support the warfighter and encourage innovative best practices throughout the armed forces.

The DIB’s mirror image in the private sector is the America’s Frontier Fund (AFF). AFF is a tech-focused venture capital outfit, whose website announced that:

The time to act is now. We are in a great-power competition, and the United States is falling behind. By 2030, we risk losing our edge in microelectronics, AI, 5 G, and quantum to our adversaries. At a time when technology advantage is strategic advantage, this is not a risk we can take.

The AFF can boast tech, financial and governmental elites among its employees. Its Board of Directors has included former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter and retired Lieutenant General H. R. McMaster, while its current CEO Gilman Louie previously served as the CEO of IQT (formerly In-Q-Tel), a public venture capital firm established in 1999 by the CIA and other US government agencies that receives well over $100 m annually in tax revenue. IQT itself ‘focuses on the 15,000+ early stage venture-backed startup companies in the U.S. and select other countries’ (IQT, 2024).

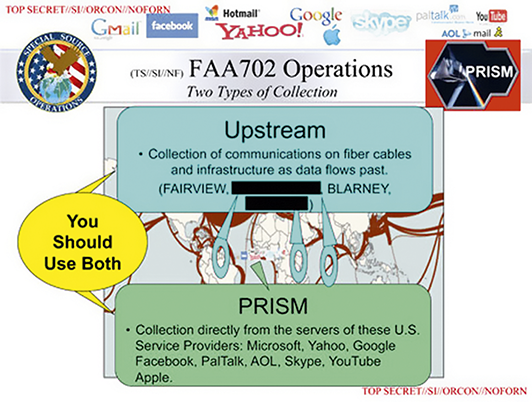

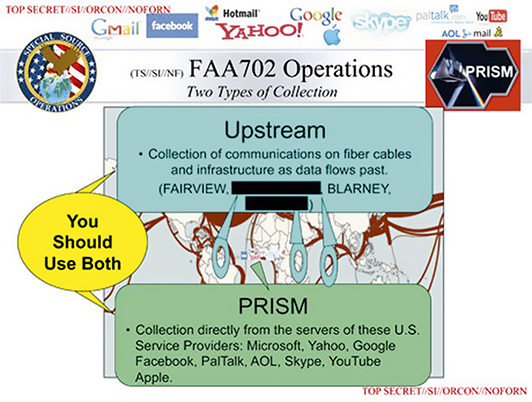

Sustained efforts by both sides to integrate digital technologies with the US military explains the explosion of government contracts with Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and Twitter since 2017.Footnote 2 The CIA signed an initial $600 m contract with Amazon Web Services (AWS) in 2013, and awarded a decade-long contract worth ‘tens of billions of dollars’ to AWS, Microsoft Azure, IBM, Google, and Oracle in 2020 for cloud computing services (Konkel, Reference Konkel2020). Similarly, the National Security Agency (NSA) inked a US$10 bn contract with Amazon in 2021 for cloud computing services (Gregg, Reference Gregg2021). Google has developed collaborative relationships with the CIA, US Navy, and Air Force as it develops a bid for the Joint Warfighter Cloud Capability contract with the Pentagon (Simonite, Reference Simonite2021). And the NSA (2022) recently established a Cybersecurity Collaboration Center it describes as a ‘groundbreaking hub for engagement with the private sector … to create an environment for information sharing between NSA and its partners combining our respective expertise, techniques, and capabilities to secure the nation’s most critical networks … [representing] a vital part of a whole-of-nation approach to cybersecurity’.

3.3 The American Pivot

Until recently, the United States largely pursued a ‘free’ global digital trade regime which upheld the dominance of its platforms globally. However, Donald Trump’s message that free trade represented a cost to the US economy has since come to form a cross-party consensus on the need for mercantilist practices, especially in the digital sphere. The Biden administration committed to protecting strategic sectors within a proverbial ‘small yard’ by a ‘high fence’ that includes export controls, investment screening, and tariffs (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2022). Such initiatives signal a broad shift in US policy, in which the global and systemic significance of US digital platforms is recognized – and safeguarding their overwhelming power is an explicit objective requiring direct and explicit forms of intervention anathema to a free trade agenda. In addition to discouraging other governments from regulating US platform firms, this is done by limiting Chinese platform firms’ access to capital, technology, and markets.

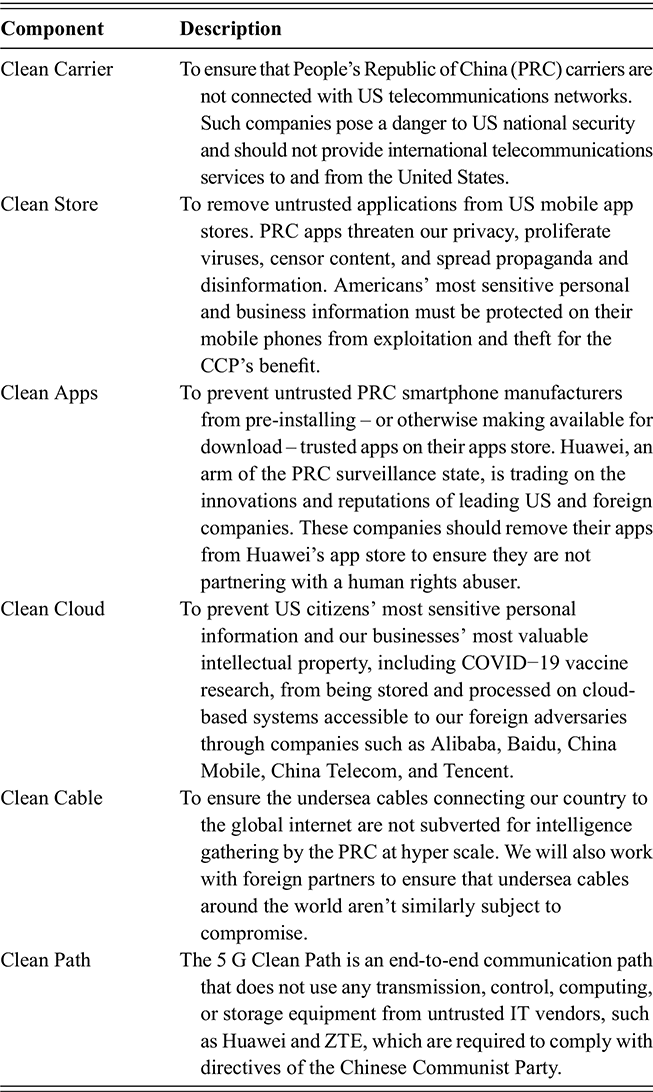

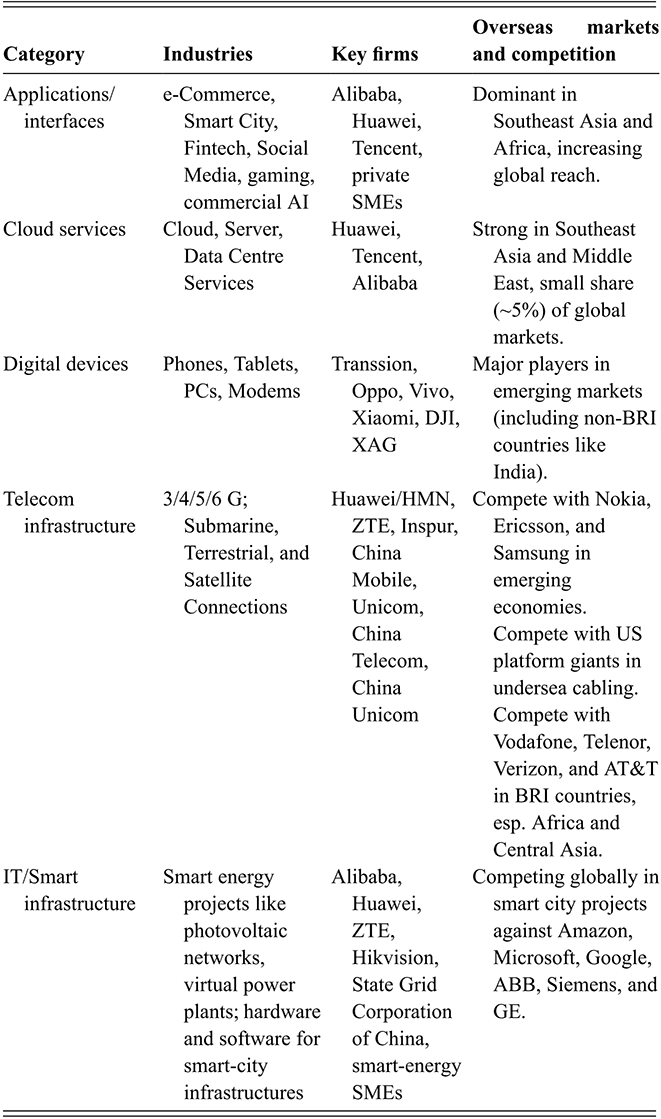

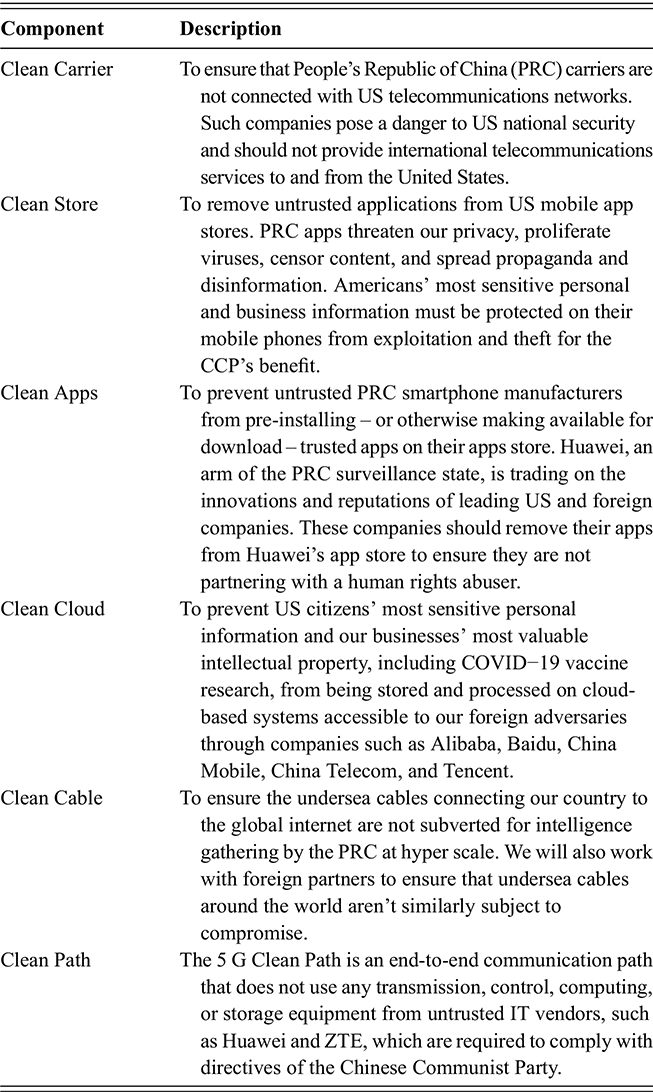

The Clean Network Initiative (Table 2) was introduced by the Trump administration, and it represented the first major rupture in the field of digital policy. Whereas previous policy underpinned globalization and prioritized free trade, the Clean Network Initiative discouraged governments and firms from working with ‘high-risk’ Chinese firms such as Huawei and ZTE that are purportedly ‘required to comply with directives of the Chinese Communist Party’ (U.S. State Department, 2021). Six fields of regulation were identified, whose collective ambition was to ‘clean’ the technology stacks of third countries of Chinese operators.

The results of the Clean Network Initiative were mixed. While it attracted broad formal support, fewer countries were prepared to make the hard trade-offs involved in ending relations with Chinese firms. A number of countries did cease doing business with Huawei: Canada commissioned Ericsson, Nokia and Samsung to build its 5 G networks, while the UK banned the installation of new Huawei equipment in 2020 and plans to remove it entirely by 2027 (Payne and Fildes, Reference Payne and Fildes2020). While it impacted Huawei’s global operations, it failed to deal the Chinese firm a mortal blow. Huawei has since recovered and even strengthened its competitive position across a widening range of product categories and services. But despite mixed results, the Clean Network undeniably altered the course of US policy.

Table 2Long description

This table lists and describes the components of the Clean Network initiative, as introduced by the U.S. Secretary of State in 2020. The components are:

1. Clean Carrier: To ensure that People’s Republic of China (P R C) carriers are not connected with US telecommunications networks. Such companies pose a danger to US national security and should not provide international telecommunications services to and from the United States.

2. Clean Store: To remove untrusted applications from US mobile app stores. PRC apps threaten our privacy, proliferate viruses, censor content, and spread propaganda and disinformation. Americans’ most sensitive personal and business information must be protected on their mobile phones from exploitation and theft for the C C P’s benefit.

3. Clean Apps: To prevent untrusted P R C smartphone manufacturers from pre-installing – or otherwise making available for download – trusted apps on their apps store. Huawei, an arm of the P R C surveillance state, is trading on the innovations and reputations of leading U S and foreign companies. These companies should remove their apps from Huawei’s app store to ensure they are not partnering with a human rights abuser.

4. Clean Cloud: To prevent U S citizens’ most sensitive personal information and our businesses’ most valuable intellectual property, including COVID−19 vaccine research, from being stored and processed on cloud-based systems accessible to our foreign adversaries through companies such as Alibaba, Baidu, China Mobile, China Telecom, and Tencent.

5. Clean Cable: To ensure the undersea cables connecting our country to the global internet are not subverted for intelligence gathering by the PRC at hyper scale. We will also work with foreign partners to ensure that undersea cables around the world aren’t similarly subject to compromise.

6. Clean Path: The 5G Clean Path is an end-to-end communication path that does not use any transmission, control, computing, or storage equipment from untrusted I T vendors, such as Huawei and Z T E, which are required to comply with directives of the Chinese Communist Party.

The Biden administration formally shelved the Clean Network Initiative, but it largely maintained and expanded the intent behind the Trump-era policy regarding technology diplomacy. The CHIPS Act,Footnote 3 the Biden administration’s flagship technology sector initiative subsidizing domestic semiconductor production, includes ‘strong guardrails, ensuring that recipients do not build certain facilities in China and other countries of concern’ (The White House, 2022a). These guardrails dovetail with a welter of new export controls aimed to starve Chinese platform giants of the advanced chips and manufacturing technologies necessary for their development of advanced networking equipment, smartphones, and AI (Ryan and Burman, Reference Ryan and Burman2024).