Introduction: Discovering Shakespearean Eco-Theatre

‘On such a full sea are we now afloat, / And we must take the current where it serves / Or lose our ventures’

‘There’s a story that begins here. Or maybe it ends. It depends on us.’ – Robin Wall Kimmerer (Reference Kimmerer2022)

What has Shakespeare got to do with the climate crisis? Conversely, what has the climate crisis got to do with Shakespeare? Rising seas, unstable temperatures, mass extinction, biodiversity loss, and resource shortages: these are not what first come to mind when picturing a long-dead white man with a ruff and a quill. But scratch the surface and Shakespeare’s imagined worlds reveal gripping tales of geopolitical conflict and environmental catastrophe alongside vivid examples of collective responsibility and the prospect of redemption. In this Element, we make the case that Shakespeare is a dynamic and infinite cultural resource that can – and should – be reused and recycled to perform stories that will help save life on our endangered planet.

We come to this view through a shared decade of trial and error, research and practice, writing and discussion, learning and understanding. We freely admit to being fans of the plays. We also freely admit to being concerned citizens. The world is experiencing polycrises on diverse fronts: social, political, and environmental; instability is the new normal. As temperatures rise, violence and aggression correspondingly increase, while focus, productivity, and empathy decline (Rich, Reference Rich2024). Amid this spiralling ecological and interpersonal disorder, we take inspiration from Donna Harraway’s call to ‘stay with the trouble’, that is, to make the best of living and dying together on a damaged earth (Reference Harraway2016: 77). We trust that with ingenuity and care, people can enable the kind of thinking that will build a more liveable future for ourselves and the fellow species with whom we share the planet. We come to the urgency that characterizes this Element through a belief in the power of art – and above all a belief in the power of embodied, collectively experienced storytelling – to bring communities together to make positive change.Footnote 1 Laurie Woolery, the current director of the Public Works programme in New York, says:

I truly believe Shakespeare is a community playwright. He is the community playwright that we get to adapt into the world order that we are living in now. And the future of Shakespeare lies in continually turning to community to guide us, to lead us in interrogating what these stories have to say to the present. (2021)

Community, of course, is defined by who is in it, and we openly acknowledge that the Shakespeare community has long been guilty of being an exclusive and privileged club, gatekeeping out rather than welcoming in.Footnote 2 Throughout this Element we advocate for inclusive communities – communities of artists, whether students, amateurs or professionals; communities of audiences, in person, on tour or online; and communities of activists, volunteer, ad hoc, or organized – as the most potent force at humanity’s disposal for enacting change.Footnote 3 This Element is an unrepentant call to arms, but is not intended to be dogmatic. We see ourselves as part of an existing and future eco-Shakespeare community and offer this volume as an empowering guide for theatre-makers, academics, and students working in all contexts and at all scales.

The Element is organized into three sections. The first section tackles questions of why: why storytelling, why theatre, why Shakespeare, and why Shakespeare in performance; in other words, what is it about this writer’s stories and this art form that particularly speak to the climate crisis? If the opening section is the why, the following two are the how, and the Element moves into practical mode for those two sections. Section 2 is mainly focused on adapting the playscript and explores play choice, editing, production goals, and extra-textual production elements. Section 3 focuses on the material production, outdoor performances, touring, and online dissemination. A final epilogue turns to the question of teaching ecological Shakespeare.

At the ends of Sections 2 and 3 are excerpts of conversations between Katie and Elizabeth, the co-authors of this Element and directors of recent eco-productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest respectively. These conversations formed an extended dialogue over five days in Stratford-upon-Avon in the summer of 2024. The River Avon in Shakespeare’s hometown (where Elizabeth lives and works) had just flooded after months of above-average rainfall. Meanwhile, on the other side of the world in California (where Katie lives and works), the temperature was regularly over 110 degrees Fahrenheit. As we worked on this Element and talked about our theatre-making experiences, in the evenings the skies over England glowed unseasonably red, caused by particles from North American and Canadian wildfires being transported over the Atlantic due to an unseasonably strong jet stream. Our individual experiences of working on eco-inflected Shakespeare were therefore framed by a joint experience of the climate crisis that shrank the miles which separated our productions. When we reconvened (online) in early 2025 to edit the manuscript for publication, Los Angeles was experiencing the worst wildfires in the city’s history, fuelled by relentless winds and tinder-dry ground conditions. Meanwhile, the World Meteorological Organisation declared January 2025 to be the warmest on record. Drought in Sudan escalated territorial conflicts, an intense heatwave in Brazil closed schools and businesses, and the already-impoverished island of Mayotte in the Indian Ocean was devastated by Cyclone Chido. We hope the transcripts of those conversations, alongside the increased sense of urgency which shaped our rewriting process, reflect our honest endeavours to articulate how and why we think it is worth performing Shakespeare on an endangered planet.

1 Why Eco-Shakespeare?

‘One touch of nature makes the whole world kin’ (Troilus and Cressida 3.3.181)

‘In order to do what the climate crisis demands of us, we have to find stories of a livable future, stories of popular power, stories that motivate people to do what it takes to make the world we need.’

The only place in the universe known to support life is in trouble. There’s nowhere to hide, no species that is immune. Worse still, floods, drought, famine, and heat are most likely to affect humans (and non-humans) who are least responsible for the changes to our Earthly home (or, as the ancient Greeks called it, our oikos, from which we get our word ‘ecology’). As theatre-makers and academics who teach, study, and direct Shakespeare, we have wrestled with the question: what can we do about this? And it turns out that the answer is: quite a lot.

Environmental activist, scientist, and writer Sandra Steingraber says that we are all musicians in a great human orchestra, and ‘it is time now to play the Save the World Symphony. You are not required to play a solo, but you are required to figure out what instrument you hold and play it as well as you can’ (Reference Steingraber1997, 289). Our instrument is Shakespearean theatre-making. In what follows, we explain:

I. Why storytelling matters to humans’ ability to address environmental crises

II. Why theatre is a particularly effective kind of ecological storytelling

III. Why Shakespeare’s work is inherently environmental, and finally

IV. Why Shakespearean performance is thus poised to be one way to address the crises facing our fragile ecosystems and amplify ways to meet our current environmental moment

1.1 Why Stories?

Environmental emergencies are crises of culture and narrative, not just of science and policy. An increasing amount of research indicates that compelling, persuasive storytelling is vital to ensuring cooperative environmental action (Arnold, Reference Arnold2018; Butfield, Reference Butfield2020; Moezzi et. al, Reference Mithra, Janda and SeaRotmann2017). Indeed, storytellers have long been at the vanguard of pushing forward environmental change. From the accessible scientific writing of Rachel Carson to the films of David Attenborough, from the poetry of William Wordsworth to Marvin Gaye’s ecological anthems, from Cli-Fi (climate fiction) novels to Potawatomie botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s books and essays, successful environmental communications have the power to not only change hearts and minds, but also to inspire local, national, and global action. International gatherings like the Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings of the UN Climate Change Conference increasingly showcase storytelling, and institutions such as the Entertainment and Culture for Climate Change Alliance (ECCA) are organizing and supporting artists and creative industries dedicated to leveraging entertainment in service of a liveable planet.

These organizations recognize that environmental communications need to be creative, not merely journalistic. In the last three decades, we have seen that communication about climate change and related, escalating threats to life on this planet have failed to lead to significant change. Genevieve Guenther, a former Renaissance literature scholar who now runs the group End Climate Silence, channels her literary training to analyse the language used by the media in its coverage of climate change (End Climate Silence, 2025). She explains that ‘in Renaissance literature, there is a rhetorical principle called energia – energy or vividness’ which means that ‘if you’re trying to persuade your reader, you need to give them vivid images that will capture their imaginations’. Guenther found that climate communications lacked this rhetorical strategy and were instead ‘too data-driven and abstract’ (qtd. in Widdicombe, Reference Widdicombe2020). While science writing and journalism are important, ‘it is now widely accepted that we need creative forms of communication’ (Hoydis et al., Reference Hoydis, Bartosch and Martin Gurr2023: 1). Creative communication – novels, comic books, films, music, and indeed plays – can:

1) make complex scientific ideas digestible and affective

2) contextualize crises in their societies and cultures

3) activate the imagination

4) soften the edge of charged and difficult conversations

When it comes to understanding the complexities of biodiversity loss, climate change, and environmental justice, presenting the facts is not enough to inspire change. For one thing, scientific language is by nature impassive and objective, which, as Guenther explains, means that it is prone to understatement that often betrays the urgency of what is being reported (Guenther, Reference Guenther2024: 19). Additionally, media outlets, marketers, and politicians ignore, lie about, and politicize the realities facing our warming planet. What’s more, the issues themselves are complex and our knowledge of them and the conditions themselves are rapidly changing. These things mean that gaining knowledge of environmental issues is difficult for many members of our society. But there’s a deeper problem, which is the fact that, according to many psychologists, knowledge itself does not necessarily lead to action (Hoydis, Reference Hoydis, Bartosch and Martin Gurr2023: 17; Pearce et al., Reference Pearce2017). Maxwell Boykoff explains that climate communication based primarily on conveying the facts fails at making the lived reality of climate change understandable for audiences who ‘must be met where they are’, and that feeling and emotion – the realm of more creative storytelling – are therefore crucial (Reference Boykoff2019, xi). Julia Hoydis, Roman Bartosch, and Jens Martin Gurr argue that neither the presentation of facts alone nor the evocation of emotion alone is enough to inspire action (Reference Hoydis, Bartosch and Martin Gurr2023: 10).

We believe that the combination of both facts and emotions can be more effective than either one on their own, and are also interested in Hoydis, Bartosch, and Gurr’s argument that creative environmental storytelling can be most effective when it ‘situates climate change within a larger cultural context’ (Reference Hoydis, Bartosch and Martin Gurr2023: 9). For indeed, the issues facing our planet are not just scientific: humans in the global north, living in increasingly rapacious capitalistic cultures, have created these issues, and those cultures must be altered to salvage a habitable planet. Storytelling can provide a clear presentation of scientific facts, give people an emotional way to access the lived realities of those facts, and contextualize facts and emotions within the cultures that environmental challenges and solutions find themselves. In the words of prolific scientist and leading climate communicator Michael Mann, effective stories emphasize both urgency, which means presenting the situation as it is without sugarcoating, and also agency, which means empowering people to recognize their ability to force change, and that it’s not too late to do so (Mann, Reference Mann2022: 182 and passim.). Stories help us understand what has happened, what is happening, and what we can do about it.

At its best, creative storytelling doesn’t merely inform, but also moves, connects, and galvanizes. When fires ravaged Los Angeles in January 2025, many pointed to Octavia Butler’s prescient novel Parable of the Sower (Reference Butler1993), which writes of uncontrollable fires in LA in 2025 (Butler herself is buried in Altadena, at the epicentre of the Eaton fire). Butler’s uncanny ability to predict catastrophe isn’t the only reason this story mattered to the moment. Throughout her now oft-cited writings, she provides models for community care in the face of catastrophe, models that inspired a Pasadena bookstore named after her, Octavia’s Bookshelf, to function as a donation centre (‘Octavia Butler Imagined’, 2025). Furthermore, adrienne maree brown’s Emergent Strategy (Reference Brown2017) and viral activism are based on principles inspired by Butler’s storytelling. The afterlives of Butler’s stories have given both readers and those casually familiar with the books or brown’s activism coping strategies and community practices that have been enacted in the real world.

Creative forms of communication can also help humans dream up better futures. Leading eco-critics and -novelists have often called the climate crisis a crisis of imagination: if we cannot envisage a decarbonized, cleaned up, cooperative world, we can’t create it (Buell, Reference Buell2005; Ghosh, Reference Ghosh2016). Literature stimulates the imagination, and research shows that the very act of imagining can ‘activate and strengthen regions of the brain involved in its real-life execution’ (Bilodeau, Reference Bilodeau, Bilodeau and Peterson2020: 16). The ecological playwright Deke Weaver uses a nature metaphor to express this idea: ‘Art can have tremendous long-term effects if it burrows into somebody’s imagination, like a seed growing into an oak tree’ (qtd. Chaudhuri and Williams, Reference Chaudhuri, Williams and Kristen2020: 81). Through literature, one of our best ‘social technologies of imagination’, we can imagine and manifest less dire futures for all Earthlings (Milkoreit, Reference Milkoreit, Wapner and Elver2016: 172).

Finally, climate change is scary; conversations about it are emotionally and politically charged. Storytelling can make these conversations more human and less difficult (see Bilodeau, Reference Bilodeau, Bilodeau and Peterson2020: xv). Jessica Rivas, at the time a park ranger in Yosemite National Park, told Katie (Brokaw, co-author of this Element) after performing in Shakespeare in Yosemite’s 2018 Midsummer Night’s Dream that

when you are addressing issues like climate change, and some of these very hard to accept and maybe even uncomfortable conversations – it’s important that we are all included, because if we are not connected to the problem, we are also not connected to the solution … This show addresses these [climate issues] and people are connecting to them, and it opens up conversations. I know in the conversations I’ve been able to have with people, I’ve been able to use words for this experience that aren’t the same words we hear in the media, those negative narratives. (2018)

In the case of this adapted Shakespearean story, the combination of emotional, social, and naturalistic elements opened audiences up to conversations that they might otherwise find off-putting, unbelievable, or frightening.

1.2 Why Theatre?

While novels, stories, poems, journalism, and essays are important forms of climate communication, we believe that theatre is a particularly effective instrument for conveying facts, emotions, and action. There are several reasons for this:

1) Drama, both explicitly environmental plays and those that have been eco-adapted, is an effective, multi-voiced literary form that can synthesize the scientific, social, and cultural complexities of environmental crises

2) When staged, drama becomes action and is expressed and experienced by bodies in space and using the real, material world

3) The more abstract forms of representation used in the theatre allow audiences to take more imaginative leaps than they would when watching a screen

4) The process of creating and viewing theatre is collaborative, a collective rehearsal of how to navigate the challenges of a climate-inflected future

Drama has long called attention to the plight of the unjustly dispossessed (Euripides’ Trojan Women), to the unfairness of resource shortage (Brecht’s Mother Courage), and to the power of solidarity and activism (Tagore’s Muktadhara). With its scripting of multiple perspectives in conflict, dramatic literature is well equipped to particularize how environmental injustices and movements to resist them play out in different communities (see Angelaki, Reference Angelaki2019: passim).

Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People (1882) tells the story of a doctor’s discovery that his town’s spa waters – a major source of municipal income – are in fact being polluted and are sickening the people they purport to heal. The town leadership’s refusal to close the spa and invest in clean-up – taking a major financial hit to save lives – well dramatizes tensions between economics and status (for the wealthy) and health and survival (of everyone, especially the vulnerable) that continue to be central to many environmental injustices. The play is thus considered the first deliberate eco-play. In the century and a half since it was written, explicitly environmental plays continue to be penned, many of them in the last fifteen or so years.Footnote 4 Plays like Chantal Bilodeau’s Sila (2010), David Finnegan’s Kill Climate Deniers (2018), Annalisa Dias’s The Invention of Seeds (2024), and the short plays staged around the world every other year as part of Climate Change Theatre Action explicitly depict threats to the humans, animals, and plants on the frontlines of environmental crises, as well as those combatting the forces of complacency.

The practice and study of such drama has been called ecodramaturgy, a word first appearing in print when described by Theresa J. May (Reference May2010). Ecodramaturgy describes any theatrical endeavour motivated by environmental concerns and the study of it provides a ‘critical framework that interrogates the implicit ecological values in any play or production’ (May, Reference May2022: 164). An ecodramaturgical production should be explicit in purpose and ‘put ecological reciprocity and community at the centre of its theatrical and thematic intent’ (Arons and May, Reference Arons and May2012: 4).

Ecodramaturgy lives at the intersection of both critical and creative practice, and Catherine Love, a theatre reviewer and academic, adds that such work needs to be made and experienced on ‘multiple, interconnected levels: form, content, and material conditions’ if it is to be deeply felt and inspiring of action (Reference Love2020: 228). Love suggests that such theatre should provide ‘an imaginative leap, allowing us to think and feel our way through what it would mean to truly believe the facts of the climate crisis and to help develop our ability to re-imagine our way of living and being’ (Reference Love2021). This eco-hopeful vision of a theatre experience that offers the potential for change feels to us one worth subscribing to.

Explicitly ecodramaturgical plays are powerful ways of engaging intellectually and emotionally with environmental issues: we have both found this to be the case in the classroom, where our students read and discuss their content, from the Bhopal disaster (Rahul Varma’s Bhopal, Reference Varma2001) to the ethics of childbearing in an age of climate catastrophe (Duncan Macmillan’s Lungs, Reference Macmillan2011) as well as the drama’s creative forms.

It is not until these plays are staged that they begin to reach their full potential and differentiate themselves from other forms of literature that only live on the page (or screen). Cognitive scientists have discovered that cognition is embodied, with learning happening via interactions of brain, body, and environment (Damasio, Reference Damasio2022; Macrine and Fugate, Reference Macrine and Fugate2022). Embodied art, as Bruce McConachie writes, is therefore well placed to mobilize ecological action (Reference McConachie, Arons and May2012: 98).

No form of literary art is more embodied than the theatre, which takes as its medium bodies, space, and material. The very things that are under threat in our world – the physical contents of eco-drama – are used to create its form. Theatre helps us think about the interactions of various bodies and materials by putting those bodies and materials in contact with each other and with the audience, and it is affected by the site in which it is performed, particularly if that site is outdoors (Fischer-Lichte, Reference Fischer-Lichte2008; O’Malley, Reference 109O’Malley2020). Being made of earthly matter both living and inert, and taking place in real space, performed theatre allows audiences a fully embodied experience.

That theatre is such a multi-sensory experience gives it a particular kind of imaginative power distinct from film.Footnote 5 We recognize the powerful reach of films – particularly popular movies; Wall-E (2008) and Frozen 2 (2019), for example, both reached mass audiences with their messages about overconsumption and Indigenous (Samí) ways of living in balance with nature. But theatre – particularly when it is staged in a way that is more suggestive than literal – leaves more room for an audience member’s personal imagination to fill in the gaps. When watching plays, one’s sense of the story is specifically informed by the faces and voices of the actors and the set and sound design, but the form is less representational in a way that allows spectators to personalize the story, to imagine woods, people and creatures dear to them, their own lost loves and threatened habitats. As Nicholas Ridout argues, the co-presence of actors and spectators makes theatre fundamentally ethical (Ridout, Reference Ridout2009: passim.).

Western theatre tends to tell linear, character-driven stories of people in conflict in particular times and places. But Amitav Ghosh suggests that environmental writers, including dramatists, need to invent new forms that better depict, convey, and communicate the crisis (Reference Ghosh2016). Theatre, or perhaps we should say performance, is equipped to experiment with such things: to use movement and myth and design and sound and multiple timeframes and interconnected locations to create new narrative forms that better speak to the peoples and issues of today. It is our contention that all kinds of theatre are needed to meet this moment: that which draws on Western forms of storytelling, that which leverages artforms and paradigms from Indigenous cultures and the Global South, new interdisciplinary genres, and work that combines some or all the aforementioned.

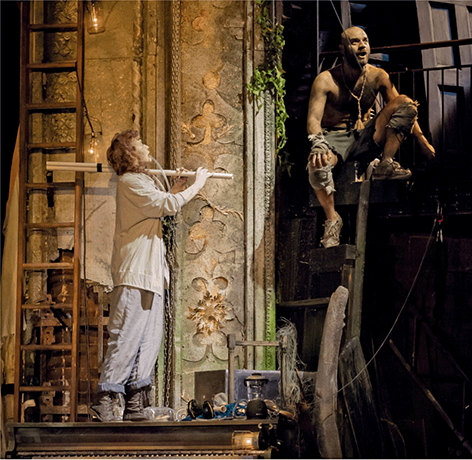

While no one story or play is likely to immediately turn a climate sceptic into a climate activist, stories accumulate. Guenther writes of how narratives and careful language about the climate crisis can plant seeds, which might be watered later by personal experiences or further stories real or imagined (Reference Guenther2024). Both climate communicators and scholars of applied theatre write of how, in Helen Nicholson’s words, theatre is less likely to offer an immediate and total transformation, and more likely to offer transportation, a ‘travelling to another world, often fictional, which offers both new ways of seeing and different ways of looking at the familiar’ (2005/14: 15). Psychologists have shown that being transported by live theatre leads to increased charitable giving and empathy as well as changes in socio-political views. One study on the matter concludes that theatre is more than mere entertainment, leading as it does to tangible increases in pro-social behaviour (Rathje et al., Reference Rathje, Hackel and Zaki2021: passim). There’s an eco-Shakespearean example of this effect: in the months after the RSC Tempest directed by Elizabeth, the local newspaper reported an uptick in interest in litter picking that was attributed to the way that production spotlighted plastic pollution (Mingins, Reference Mingins2023).

Finally, the making of ecological theatre – and all theatre – is a collaborative, creative act that rehearses the very kinds of collaborative, creative acts that are needed to mitigate environmental crises. Only by working together – all humans with regard for each other and for the Earth’s animals and plants – can we safeguard our planet and ourselves. Efforts to save a habitable planet reach across ideological divisions, involve improbable collaborations, and demand sacrifices and compromise. Theatre work lets us imagine stepping over psychological boundaries and ideological thresholds, rehearse for our future selves, and practice the conversation with our grandchildren about what it was like to live during the end times.

Theatre is a safe rehearsal space for both makers and audiences to role-play alternative ways of being: this is why hope and possibility are so important to communicate. All kinds of literature can depict what is possible, but in the theatre, such visions are not just fed into the singular imaginations of author and reader, but also absorbed into collective imaginations: one sees and feels their fellow audience members experiencing the same story in real time, allowing each person to sense they are part of a movement of people who care about similar things.

We humans must get in shape for what is to come: we must exercise our imagination muscles, our collaboration muscles, our empathic muscles. In the ancient origins of theatre – in Asia, in Greece, in myriad Indigenous societies – theatre was a shared space in which to work the mind, body, heart, and social imagination in service of addressing a society’s problems (see also Kulick, Reference Kulick2023). In the intervening time, theatre has moved away from its civic function and become more internal and passive, but we need it to once again become a societal training ground.

1.3 Why Shakespeare?

What has all this embodied narrative ambition got to do with a dead white guy? We’ll now go on to explore four ways in which Shakespeare’s plays can be unpuzzled to speak to today’s climate crisis.Footnote 6 These are:

1) His own lived experience of climate change is charted in the plays, including deforestation, the use of coal for domestic heating, and globalization

2) His lifetime was a crucible moment of human understanding of the universe, situated between Copernicus and Galileo

3) Scientists have date-stamped his time of writing to the beginnings of the Anthropocene, the geological epoch the Earth is now in

4) The content of his plays includes elemental extremities, populist power struggles, the animation of flora and fauna, and meditations on communality and the social good

Before that, though, let’s do a quick rewind:

The long intellectual alliance between ecology and literature was granted its own terminology when Walter Rueckert coined the term ‘ecocriticism’ to describe analysing language through an environmental lens (Reference Rueckert, Glotfelty and Fromm1978, Reference Rueckert, Glotfelty and Fromm1996). The first decades of this newly titled discipline focused on Romanticism, and re-examined the nineteenth-century poetic canon in light of industrialization and its environmental ills. Ecocriticsm then broadened to take in literary movements as diverse as Greek pastoral, the American Transcendentalists, and Sci-Fi.

The relatively newer field of Shakespearean ecocriticism emerged out of Shakespearean nature studies, quickly outgrowing straightforward interrogations of Shakespeare’s abundant flora and fauna imagery to examine, for example, how weather impacts the action of the plays or correlations between Shakespeare’s changing environment and our own.Footnote 7 Noting the underpinning activism of many such ecocritical approaches, Gabriel Egan acknowledges the immediacy of the task at hand: ‘our current environmental crisis is not merely a discourse … but an urgent historical conjuncture that forces us to rethink the role of scholarship’ (Reference Egan2006: 2). Ecocritical research explores issues such as ecophobia in Othello, Coriolanus, and other plays (Estok, Reference Estok2011), agricultural cultivation and gendered forms of husbandry in A Winter’s Tale (Munroe, Reference Munroe, Bruckner and Brayton2016), and the concept of bastardy in the context of native and invasive species (Saenger, Reference Saenger2016).

These studies move between approaches as varied as place studies, geo-historical research, post-humanism, and multispecies relations, roving across disciplines with a free-wheeling energy. Despite some naysayers suggesting that early modern environmentalism is by definition anachronistic, this kind of ecocriticism, its scholars stress, is driven by the thought that ‘we cannot make contact with a past unshaped by our own concerns’ (Grady and Hawkes, Reference Gray and Hawkes2007: 3). Whether any individual cares or not, environmental change dominates humans’ daily experiences, on both a micro and a macro level. So how could practitioners not view Shakespeare through this prism? It would require enormous energy not to do so.

Shakespeare’s texts have proven themselves to have boundless artistic longevity, relevant to a myriad of contexts. But what is it about the time in which Shakespeare was writing that particularly lets his work speak to the current ecological moment? Our proposition is that Shakespeare can be read backwards like an ecological time capsule, or forwards as a how-to guide for existing in the end times.

For one thing, he lived through the so-called Little Ice Age. This was a period of atmospheric cooling in the northern hemisphere spanning the fourteenth to eighteenth centuries, with a particularly pronounced cold snap in Shakespeare’s lifetime.Footnote 8 Randall Martin draws direct lines between historical weather phenomena to illustrate the context behind the action of the plays, like the real-world failure of crop harvests that inspired the populist riots in Coriolanus as well as Corin’s farming struggles in As You Like It (2015). Shakespeare’s environmental experiences are embodied in the plays, his writer’s instinct to dramatize the issues of his time means that environmental phenomena are encoded in his work. When the fairy queen Titania laments how the ‘seasons alter’ in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, there is an uncanny sense of Shakespeare’s lived experience of seasonal volatility speaking across the centuries (2.1.110). We are also living through a ‘distemperature’ (2.1.09).

Given the unsettled weather patterns around the globe then and now, certain plays are ripe for ecocritical study. There are the ‘green’ plays with forests, like A Midsummer Night’s Dream, As You Like It, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and A Winter’s Tale, and the ‘blue’ plays with shipwrecks, oceans, and rain like Twelfth Night, Pericles, The Tempest, and King Lear. The forest plays are seen to speak to deforestation, a practice which was ratcheting up at an alarming pace during Shakespeare’s lifetime. The partial destruction of Warwickshire’s Forest of Arden happened while Shakespeare was alive thanks to the Elizabethan obsession with building ships for colonizing expeditions. Several of the plays also mention enclosure, an agricultural practice that divvied up communal grazing land between individual owners. Animal husbandry intensified in this era, and Shakespeare’s Midlands became the most enclosed part of England (Lipson, Reference Lipson1931). Then there is the concurrent and well-documented change from timber to coal to heat people’s homes, a shift referenced across the plays in, for example, Mistress Quickly looking forward to ‘the latter end of a sea-coal fire’ (The Merry Wives of Windsor, 1.4.411). Such examples are specific incidences of humans altering their environment which had, and have, direct consequences both for Shakespeare’s fellow planet-dwellers and ours today.

Helpfully, fictional references are backed up by a wealth of contemporaneous scientific documentation. The sixteenth century is often used as a baseline by conservation and climate organizations including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) because this era saw hobby naturalism evolve into the emergent fields of botany, atmospherics, and zoology; several notable compendiums (see Gerard, Reference Gerard1597; Parkinson, Reference Parkinson1640; Topsell, Reference Topsell1607) were published recording species and phenomena encountered contemporaneously. As western peoples began to spread across the world, travelogues and reportage of the lands and Indigenous peoples they encountered provide benchmarks for a pre-industrial, pre-Enlightenment, pre-globalized world. These primary records enable modern experts to draw on quantifiable source material to establish comparative datasets. It is thanks to Early Modern taxonomy that things like current extinction rates are charted with such confidence.Footnote 9

But it’s not just the biological science. Philosophically, Shakespeare helps shed light on an extraordinary moment in time. He lived his life during the fallout between Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres (1543) and Galileo’s condemnation (1633), when human understanding vacillated between exceptionalism and humility, supposition and knowledge, faith and fact. His astronomical peers were operating in a period of consequential debate, literally trying to figure out how the world worked, and Shakespeare was quick to embody this febrile period of discovery in his characters and stories. Hamlet’s contemplation of what constitutes the ‘brave o’erhanging firmament’ is one such attempt to wrestle with humanity’s place in the universe (2.2.1394).

The so-called New World discoveries that also characterize this time provide the most disturbing and, for us, morally imperative reason for working with Shakespeare as our climate crisis guide. Humankind is now widely acknowledged to be living in a new geological epoch. The gnat’s breath of Homo sapiens’ appearance in the timeline of the earth’s long and eventful history had initially coincided with the epoch known as the Holocene but, thanks to people’s unique ability to irrevocably damage their own home, humanity is now in the Anthropocene, the age of people, ‘from the Greek anthropos meaning ‘human’ (Crutzen & Stoermer, Reference Crutzen and Stoermer2000).Footnote 10 This title (yet to be formally approved by the International Commission on Stratigraphy) admits that the presence of carbon in ice cores, the irreversibility of plastic in sedimentary layers, and the un-erasable radiation from nuclear events means humans can no longer pretend to have only had surface impact on the planet. Humans have fundamentally, geologically changed the Earth. But when exactly did this shift from one geological epoch to another begin? One strong contender is Shakespeare’s lifetime.

There are two conditions that must be satisfied for a new epoch to be date-marked. The first is ‘evidence of long-lasting change’ (tick). The second is evidence of a ‘golden spike’, a moment when there is a clear delineation between one geological epoch to another (Zalasiewicz et al., Reference Zalasiewicz, Waters, Williams and Summerhays2019). Some scientists think 1945 is this moment, the entrance into The Atomic Age; others look to mass industrialization in the 1800s. A third option is 1610, in a theory known as the Orbis Spike, proposed by Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin as the biocultural marker for the beginning of the Anthropocene (Reference Lewis and Maslin2015). This precise date just happens to be the year that Shakespeare wrote The Tempest, a play that speaks to climate concerns through the frame of European colonialism.Footnote 11

The Orbis Spike casts the extractive behaviours of early colonial European powers as the catalytic culprit for the Anthropocene. Lewis and Maslin found their evidence in Antarctic ice cores, which show a dramatic dip in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels in 1610. They theorize this was caused by the dramatic decline in population numbers due to an estimated forty million people being exterminated during the 1500s, largely in the New World, largely because of diseases imported by European colonizers. Because many of these people were farmers, fields were no longer tended and plants and trees were able to take a greater quantity of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, thus resulting in a sudden downward spike in the ice records. The acknowledgement of the terrible impact of this ecological imperialism means Shakespeare’s work and lifetime can be seen as coinciding with the beginning of the end times. This makes him a chronicler, a frontline cultural reporter from the moment when the Earth changed forever.

Therefore, Shakespeare is our ecological contemporary. People alive today exist in the same geological epoch and the same sixth mass extinction event as him (Kolbert, Reference Kolbert2016). Industrialization began on his watch and has continued into ours. In her pro-presentist argument, Sharon O’Dair urges Shakespeare ecocriticism to use Shakespeare’s popularity to ‘galvanize millions of people to act – and to do so quickly’ (Reference O’Dair, Bruckner and Brayton2011, 81). That’s a way of summarizing our activist-theatre-maker stance in this Element: we learn from the historical record in the plays and apply the lessons to our present-day troubles.

Climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental justice are complex ideas that require us to think deeply into the past and project ourselves forward into the future.Footnote 12 Equally, perspectives on the environment are diverse. There is not one solution, nor one universal global experience, nor is there collective culpability.Footnote 13 Shakespeare knows what the world is up against, socially and culturally. He dramatizes political struggles, heroes and villains, self-denial, wilful ignorance, the brave truth-telling of Kent and Paulina, the power of the people. Shakespeare’s plays lend themselves to the intersectional thinking that ensures the vulnerable are not forgotten, like eco-feminist takes on Macbeth, interpretations of Othello that centre environmental racism, and eco-ableist readings of Richard III. These are issues which Rebecca Laroche and Jennifer Munroe describe as ‘the interplay between forms of subjugation’ (Reference Laroche and Munroe2017, 5).

Containing multitudes and having been appropriated for causes across political spectrums, the plays are full of precisely the sort of contradictions that will need to be navigated in the coming decades: moral clarity and consistency will be rarer than one might like. Indeed, Shakespeare himself may not have been the eco-ally we’d like him to be.Footnote 14 Because of the complexity of the work, the man, and his era, Shakespeare can be eco-appropriated in any number of ways: Shakespeare as punching bag (ooh, he’s a guilty white man); Shakespeare as contemporary (ooh, he’s just like us); Shakespeare as visionary (ooh, he’s an eco-prophet); Shakespeare as allegory (ooh, this speaks to that); Shakespeare as advocate (ooh, he champions this cause). He can be any, all, and more of these things and, to be blunt, if he doesn’t like it, there’s nothing he can do about it.Footnote 15

Liz Oakley Brown says that ‘the question of humankind’s place in and power over pre-modern and modern ecologies is a puzzle that Shakespeare’s works confront’ (Reference Oakley-Brown2024: 72). We would add perennially confront: this out-of-copyright author with the most prominent name recognition in the history of global culture is a useful antidote to cultural amnesia. In their books, essays, and conferences, eco-critics have helped us understand Shakespeare’s ecological capaciousness. Across the dizzying array of ecocritical literature, however, the most notable absent voice is the theatre-making community. When Fred Waage admits he has a ‘hollow feeling that an ecocritical Shakespeare really can’t affect what people feel about the environment’ (Reference Waage2012: 219) he overlooks the places where experiential immediacy might be most readily found: rehearsal rooms and performance spaces.Footnote 16

1.4 Why Shakespeare Theatre?

Lighting the Way, a collection of Climate Change Theatre Action (CCTA) plays from 2019, documents how many productions of their new plays about the climate crisis had trouble with ticket sales. CCTA are considering changing their name to make it more appealing to people who don’t want to see a ‘gloomy’ climate play. They also found that ‘the majority, if not all, of the audience was likely to be sympathetic to the cause of climate change action’ (Bilodeau, Reference Bilodeau, Bilodeau and Peterson2020: 46).

If the main barrier to climate-inflected theatre is that not many people want to see it, and that those few who do are members of the proverbially pre-converted choir, what’s to be done?

Enter Shakespeare.Our gambit is that ‘who wants to see some Shakespeare?’ is more likely to induce an affirmative answer than ‘who wants to see a climate change play?’ That might be, for many people, a choice between the lesser of two evils, but in the face of the rising seas, we’ll take the good where we can. Performed Shakespeare has several advantages as a form of environmental communication:

1) The name recognition factor, ubiquity, and canonicity of Shakespeare can be deployed to maximize impact

2) Shakespeare’s out-of-copyright works can be infinitely adapted in ways that speak to both local and global contemporary concerns

3) Shakespeare has a ‘Trojan Horse’ capacity that invites larger audiences to see his plays than might see a new, environment-specific play, and can evade censorship

4) Shakespeare is often performed outdoors, allowing plays to draw attention to the natural world in real time

The bare truth is that most people around the world, of whatever nationality or background, have heard of Shakespeare. Most adults can name some play titles, and many even have a sense of a few plots. People tend to know, for example, that Romeo and Juliet is, to misquote Lady Gaga, some kind of sad romance. There’s a general sense that A Midsummer Night’s Dream has fairy comedic vibes. There is a long global history of student, amateur, community and professional Shakespearean theatre-making, as well as famous actors taking on his iconic roles on stage and on film. Your local dentist might have played Juliet, and so has Claire Danes. This hypercanonicity can be leveraged.Footnote 17 Instead of shying away from this ubiquity, it can be carefully used to tell urgent new stories about the planet. As Alys Daroy and Paul Prescott write, ‘this is not a question of ancestor worship, but species survival’ (Reference Daroy and Prescott2025: 2).

Harnessing Shakespeare’s social capital also means wrestling with the fact that Shakespeare has long been weaponized. People’s initial encounter with his works is often deeply problematic. The language is a barrier, making people feel excluded, denied access due to the difficulty of the dense diction and twisted syntax (more on this in Section 2). The British used him to force the English language and its poetry upon its millions of subject-inhabitants in its global empire, and he continues to be used as a tool of cultural oppression and suppression in some regimes today. This imperial legacy draws on the traditional, hierarchical, Christian worldview that Shakespeare was writing from and wields it to exert social dominance and project an image of cultural superiority. His work contains some deeply offensive material including racist, misogynist, and ableist language and themes, as well as myriad examples of ‘othering’. To see the canon as a simplistic vehicle for social justice, and to rely solely on a general, liberal understanding of the texts is to whitewash this history and deny these aspects of Shakespeare’s legacy. Using Shakespeare justly requires clear eyes about the ways he has been used unjustly (Espinosa, Reference Espinosa2021; Ruiter, Reference Ruiter2021; Thurman and Young, Reference Thurman and Young2023).Footnote 18 We do not advocate for exonerating Shakespeare or his work from this legacy, but instead acknowledge it, teach it to our students, and handle it carefully and intentionally in our production processes.

We take inspiration from the way Shakespeare has been used in a kind of reverse appropriation: artists have re-engineered his work to speak to democracy and human rights and to take umbrage with the dominant social group.Footnote 19 Examples include the adaptive work of Chicanx playwrights (see Borderlands Shakespeare Collectiva, 2024), the Indigenous American company Amerinda, and the way Shakespeare was used in the context of Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh protests in 2019 or the Umbrella Democracy protests in Hong Kong in 2014. A more specific recent example: Argentine director Monica Maffía’s production of Cymbeline framed Shakespeare’s story through a contemporary Argentine perspective by drawing on an Indigenous origin story which replaced Shakespeare’s Christian and Roman gods with those from the Tehuelchen mythological pantheon. By reclaiming divine authority, this adaptation created a counter-narrative that translated the exploitative European behaviours in Cymbeline into an empowering anti-colonial gesture. These examples all utilize Shakespeare’s broad appeal and universal name recognition to speak directly to abuses of power, tyranny and oppression.

There is one simple reason why it is possible to both wrestle with and re-appropriate Shakespeare in this way: he is out of copyright (in fact, his work predates the idea of copyright, so he has never been in copyright). The artistic freedom that comes with this, and the fact that there are no royalties to be paid for performing his plays, goes hand in hand with the ubiquity of his work. Shakespeare is an endlessly renewable cultural resource. Rewrite Romeo and Juliet and you haven’t damaged the one Shakespeare wrote. There are of course many other writers who are similarly out of copyright, from Indigenous tellers of folktales to ancient Greek dramatists to nineteenth century icons like Ibsen and Chekhov. There are also writers contemporaneous to Shakespeare who wrote plays that might be easily eco-appropriated, like Christopher Marlow’s Doctor Faustus and John Heywood’s The Play of The Weather, amongst others. But none of these has the global name recognition factor of Mr. W.S.

Not only can Shakespeare’s plays legally be adapted in myriad ways, but also they lend themselves to this practice. To borrow Emma Smith’s useful phrase, his plays are full of ‘gapiness’ (Reference Smith2019: passim). He never seems to quite come down on one side or the other. Audiences find themselves cheering on both king and rioting populace, moved by Bottom’s terrible acting, or laughing at the mass murderer Richard III. Right and wrong isn’t binary and the mess of humanity in all its charms and contradictions is on display. This interpretive promiscuity offers multiple opportunities for theatre-makers to create all sorts of meanings out of these plays that are relevant to the twenty-first century.

Shakespearean adaptations can be heavily localized, allowing us to see ourselves as part of both our own ecosystem and the worldwide eco-network, and, conversely, to think about how global decisions affect local realities. Unlike a new eco-play, for example, his words can be adapted, becoming bespoke for the community by and for which they are performed; they can meet people where they are and speak to their particular climate realities. The plays aren’t universal, but they are malleable; to use Emily Greenwood’s helpful neologism, they are ‘omni-local’ (Reference Greenwood2016: 43–44).

Shakespearean drama can do many things at once. Thinking back to the climate science history encoded in the plays, they can be factual; but thinking of theatre’s potent ability to make change, they can be affective. Eco-Shakespearean productions can inform but shouldn’t only inform. They can rail at past injustices, grieve current pains, and offer hope. They offer opportunities for the voiceless more-than-human world to be heard. They create a place in which a sense of past, present, and future come together to invite people into the conversation (for a free comic book version of the aforementioned thoughts, see Brokaw and Curington, Reference Brokaw and Curington2024).

The Shakespearean collision of past and present, Lynne Bruckner writes, ‘is Shakespeare in the ecotone – letting the archival and presentist collide, even compete, to achieve something that matters’ (2011: 245). Theatre-makers have long been best poised to ‘achieve something that matters’ in this way. For modern-day theatre-makers, Shakespeare has never been relegated to the deep past; his writer credit is listed in the programme alongside the lighting designer and actors. Diana Henderson calls this practice a way to ‘collaborate with a dead man’ (Reference Henderson2006: 8). His is a live presence in real-time, real-world dialogue with the fellow creative voices in the rehearsal room, where the required leaps of imagination are easy to make. If global warming is a ‘literary problem’, as Bill McKibben claimed long ago (Reference McKibben1989: 158), the theatre-making environment might be the best place in which to marry the time for analysis with the imperative for action.

Simple as this solution sounds, the notion raises questions. What is an ecodramaturgical production? One in which environmental themes are amplified through textual, production, or performance choices? A production which has been created using low-carbon production techniques? Is it simply a production that takes place outside, that is, in the environment? We suggest all and any of these can be ecodramaturgical if they want to be. Why argue about what to call the fire when there is a fire? Taking in past, present, and future, theatre-makers can construct fictional worlds in ecologically responsible ways while amplifying environmental narratives both inherent in, and transposed onto, the text.

This eco-adapted Shakespeare can find an audience. Shakespeare’s plays have much to teach us about our environmental moment, but this is not immediately obvious to most. This is a theatrical advantage. Not everyone wants to hear about the climate emergency, either through denial, exhaustion, anxiety or censorship. As we were finishing revisions of this Element in February 2025, the US federal government had begun issuing orders to universities and arts organizations receiving federal grants that they needed to stop talking about environmental justice and climate change or face defunding or even investigation. In the contexts of both understandable climate fatigue and the malicious suppression of environmental truths, Shakespeare can be a useful Trojan horse. The cover granted by this politically neutral-seeming, canonical author allows theatre-makers to dodge censorship and reach people who wouldn’t otherwise listen, or didn’t know they were able to hear. Many companies have realized that Shakespeare is one of the theatre-making community’s best hopes for making a meaningful contribution to saving a habitable planet, and their work is highlighted in this Element and documented in appendices A and B (see also Daroy and Prescott, Reference Daroy and Prescott2025 and Martin and O’Malley, Reference Martin and O’Malley2018).

Finally, these inherently ecological plays are often performed outdoors (see Figure 1).Footnote 20 There is a long global tradition of outdoor Shakespeare: audiences gathering under the stars, as Shakespeare’s audience would have done at the open-roofed Globe Theatre in London, to experience tales of love and wonder, power and magic. Because most of the plays were originally staged in the open air and with little in terms of set, they can still be staged in the open air, with little in terms of set. These royalty-free plays are not only adaptable, but portable.

Figure 1 Shakespeare in Yosemite’s outdoor setting in Curry Village, Yosemite National Park.

Outdoor-situated Shakespeare provides many opportunities to draw attention to local ecological conditions, be that the difference between the weather as presented in a play and the weather as experienced by the audience (O’Malley, Reference 109O’Malley2020), a production location’s flora and fauna (Macfaul, Reference MacFaul2015), or the visible impacts of industry and environmental policy (Borlik, Reference Borlik2024). Shakespeare productions happen around the world, on beaches or in city parks, upon grass or tarmac, for passers-by or paying public; all of these locations can be leveraged to relate the play’s world to the audience’s immediate environment.

As we wrote previously, we recognize that a play’s impact on audience members is hard to measure, and that it is rare that a work of art will, upon one’s first encounter with it, completely change someone’s mind. But works of art – including works of adapted Shakespeare – can provide information, provoke new feelings, and inspire more prosocial behaviour. These might be called micro-progressions.Footnote 21 And they add up.

The great Afrofuturist writer Octavia Butler was once asked, ‘well, what’s the answer?’ ‘There isn’t one,’ she replied. ‘No answer? You mean we’re just doomed?’ She smiled. ‘There’s no single answer that will solve all our future problems. There are thousands of answers, at least. And you can be one of them if you choose to be.’ All Shakespearean theatre-makers can be one of the answers. This section has shown why, and the next two sections will show how.

2 Eco-Themes, or How to Select and Adapt Shakespearean Texts for Eco-performance

‘Nature should bring forth / Of its own kind all foison, all abundance’ (The Tempest 2.1.179–80)

‘If we were able to unshackle our imaginations in this moment, I think our compatibility with the Earth would become possible’ – adrienne maree brown (Reference Brown, Solnit, Young and Bua2023: 151).

This section focuses on adapting Shakespearean plays into ecological dramas. When it comes to selecting and adapting a Shakespeare play so that it can address environmental issues, we believe that productions should be hopeful, goal-oriented, accessible, and energizing.Footnote 22 Preparing a Shakespearean playscript for ecological adaptation thus involves four processes:

I. Selecting a play that can end with hope, however fragile, rather than despair

II. Setting intellectual, emotional, and social goals for a production, and building a cast and team who can best reach these goals

III. Adapting Shakespeare’s text(s) by cutting, lightly amending, and even importing lines from other plays

IV. Enlivening shows with extra-Shakespearean elements like new writing and music

After describing each of these, this section concludes with a discussion between us, Elizabeth and Katie, about why we were drawn to The Tempest and Midsummer Night’s Dream, respectively, for our productions for the Royal Shakespeare Company (2023) and Shakespeare in Yosemite (2024); our goals for these productions; and how we used the text and extra-textual elements to adapt our shows.

2.1 Play Selection: A Case for Comedy and Tragicomedy

The climate crisis is more terrifying than any horror film. The loss of lives – human and non-human – from heat, pollution, fire, and flood is tragic. The fight against the forces of greed and indifference that cause these tragedies is epic. And Shakespeare gives us plays with barren heaths, monstrous storms, gruesome deaths, rapacious behaviour, and the consequences of taking ‘too little care of these things’ (King Lear 3.4.38). Yes, tragedies can be steered ecologically: the National Theatre’s 2018 Macbeth, LaTrobe University’s 2017 King Lear, and Montana InSite Theatre’s 2019 Timon of Anaconda were all powerful pieces of ecological theatre (see Appendix B). However, we suggest that comedy and tragicomedy are best suited to making eco-theatre because:

1) Feelings of despair, which genres like tragedy and horror provoke, do not necessarily motivate action

2) Shakespearean comedies and tragicomedies often evoke what Northrop Frye famously called ‘the green world’ (Reference Frye1957), and lend themselves to the idea of earthly stewardship

3) Comedies and tragicomedies often feature imagination-stretching moments of the fantastic that can expand people’s sense of possibility

4) Comedies and tragicomedies feature the social actions needed to build a more just world, like forgiveness, love, and community repair

Psychological research has shown that despair, a feeling one may be left with after a brutal experience of tragedy, can inhibit action and empathy (Hoydis, Reference Hoydis, Bartosch and Martin Gurr2023: 17). And in terms of their imaginative capacity, tragedies are not particularly helpful; in Chantal Bilodeau’s words, ‘if we only imagine the worst, the worst is what we’re going to create’ (2020: 18). We know that productions can do more than make us depressed, fearful, or resigned to a grim fate. Rebecca Solnit, in calling for new and hopeful climate stories, writes that ‘apocalyptic thinking is due to another narrative failure: the inability to imagine a world different than the one we currently inhabit’ (Reference Solnit2023). It is not that eco-productions of Shakespeare should avoid provoking feelings of grief and fear in audiences, and in fact both of us have found it crucial to stage moments of eco-grief in our productions, to invite our audiences to join our actors in mourning what has been lost. That grief makes the play’s hard-won hope both more realistic and more emotionally powerful.

Additionally, many of Shakespeare’s comedies and tragicomedies borrow tropes and ideas from one of the oldest and most persistent literary subgenres: the pastoral. From the garden of Eden to medieval visions of paradise (a word that literally means enclosed park) to the forest of Arden, stories of retreat into wilderness that leave people better reconciled to each other and to their natural world are naturally ecological. The pastoral mode is not unproblematic: these stories often dangerously erase the presence and labour of Indigenous peoples, and they can reinforce imagined divisions of civilization from uninhabited wilderness that distract people from the reality that we are all dependent upon complex ecosystems for survival (John Muir’s accounts of Yosemite are a classic example of both these pastoral pitfalls). Terry Gifford thus proposes that contemporary artists might aim for a ‘post-pastoral’ that suggests ‘a collapse of the human/nature divide’, a kind of literary experience that recognizes the interconnectedness of all environments, from urban to rural to protected wilderness (Reference Gifford and Westling2014: 26). Shakespeare’s comedies and tragicomedies are ripe for being adapted into post-pastoral stories. We might also think about how Shakespearean performance can be pastoral in both senses of the word, by evoking both the so-called green world and the need to care for it.

Comedies and tragicomedies are also laden with what Timothy Clark describes as ‘modes of the fantastic’ that can break down distinctions between character and environment, showing humans’ connectedness to the world around them (Reference Clark and Westling2014: 81). Tales of wonder have a long tradition, from Indigenous creation myths to medieval tales of Celtic Otherworlds and Arthurian stories like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, all of which often overlay pastoral conventions with the fantastic (Siewers, Reference Siewers and Westling2014: 31). Shakespeare’s comedies and tragicomedies are full of fantastical moments – descending gods, flying fairies, the entrance into a forest – that allow theatre-makers to stage what Deke Weaver calls ‘plain old wonder’ that provoke ‘awe at the mystery and enormity of all that we are about to lose’ (qtd. Chaudhuri and Williams, Reference Chaudhuri, Williams and Kristen2020: 80, 81). In reminding us of the precious splendour of things greater than ourselves, these feelings of awe can also inspire resolve to save what’s threatened. For indeed, psychologists have shown that feelings of awe – induced most consistently by vast landscapes and complex works of art – make people feel humbler, kinder, and more cooperative (Allen, Reference Allen2018).

The emotional arc of comedies and tragicomedies might also prompt audiences to leave the theatre feeling humbler, kinder, and more cooperative. As a society, it is important that we move from narratives of catastrophe and dystopic aftermaths and instead imagine collaborative solutions, something that is seen in numerous Afrofuturist and Indigenous stories and novels. Adapted Shakespearean comedies can be solution narratives, too. These stories show humans working together to overcome grief, fear, and strife. They stage intergenerational forgiveness and community repair, and, as a final image, give audiences the heartening sight of a massive number of very much alive people on stage.

A survey of audiences who attended Climate Change Theatre Action events in 2019 revealed that the most popular elements of these short plays involved humour, community, or hope (Bilodeau, Reference Bilodeau, Bilodeau and Peterson2020: 45); year after year, Shakespeare in Yosemite’s audience surveys say much the same. Many spectators write about how being in community while experiencing a story that ends with hope gives them a renewed and motivating sense of solidarity and possibility.

The hope that we speak of when we talk about the endings of eco-Shakespearean plays is not naive optimism. It is closer to what Rebecca Solnit, in her book of the same title, calls ‘Hope in the Dark’, a hope ‘with an imagination adequate to the possibilities and the strangeness and the dangers on this earth at this moment’ (Reference Solnit2004, 5). When we speak of humour, we do not suggest provoking laughter that is facile or gratuitous. Writing about the eco-possibilities of the medieval play of Noah’s flood put on by the citizens of Wakefield, England, Brian Kulick explains that ‘laughter both draws us in and opens us up. We collectively let down our guard when we laugh. At that point, the author can now speak of more serious matters’ (2023: 85). In our own work and conversations with audiences, we have found that both humour and music function in the heart-opening, community-building way Kulick describes, and this observation is borne out by sociological research (Chattoo et al., Reference Chattoo, Feldman and Lear2020).

2.2 Setting Intellectual, Emotional, and Social Goals for a Production and Building a Team

Once a play is chosen, the leadership team sets their goals for the production, which will inform choices related to adapting the script, casting, rehearsing, designing, and marketing. The previous section proposed that ecological theatre can:

1) Inform audiences of environmental truths (the science), as well as the biological and political challenges that both complicate and enable environmental solutions

2) Prompt people to have emotional, empathetic experiences related to ecological crises and their impact on the human and more-than-human world

3) Contextualize environmental crises in particular communities to provoke senses of solidarity and determination, inspiring action and discouraging complacency

In addition, it is crucial that a production’s leadership

4) Build an inclusive on- and off-stage team that is representative of the community’s demographic and social diversity

Ideally, when adapting Shakespeare ecologically, a director has clear goals for categories 1–3: they have thought through what they want audiences to learn, some of the things they hope they feel (emotional responses will of course vary among spectators), and how they want them to link this learning and emotion to their own community in a way that inspires resolve and action.

When casting the show and recruiting the behind-the-scenes designers and crew, it is important to practice what Alys Daroy and Paul Prescott call ‘ecological casting’, that is, building casts and teams that reflect the production’s home or oikos (Reference Daroy and Prescott2025: 140). The people working on a show should bring myriad lived experiences to the process, and audiences should see a reflection of their world’s diversity on stage. It is not just that audience members are likely to feel more included and motivated if they see themselves on stage, but also that women and people of colour are on the frontlines of ecological calamity and the fight for environmental justice, and – deviating from casting in Shakespeare’s day – should be well represented in a production’s decision-making process and cast.

Throughout the production process, the team can think through how their goals interact with each other: how ecological information interacts with the kind of emotional experience some scenes might provoke, and how the knowledge gained and feelings provoked are rooted in a particular time and place that audiences will care about, be that the time and place of production (like California in 2024, for Shakespeare in Yosemite’s Dream, see Figure 2) or another time and place needing the world’s attention (like island nations on the frontlines of the climate crisis in the RSC’s 2023 Tempest). Every audience member walking out of a production might not be able to articulate what they learned from it, how they felt about what they saw, or their newfound resolve in any consistent way, and nor should they. A diversity of audience responses indicates that a show is not mere propaganda, and that spectators represent a variety of backgrounds and experiences. Nonetheless, having intellectual, emotional, and social aims for a production can productively focus a team on how best to convey environmental crises and solutions.

Figure 2 Cast and crew of A Midsummer Yosemite’s Dream, Yosemite National Park, 2024.

2.3 Adapting with Shakespeare’s Language

Many of Shakespeare’s plays are full of ecological language: John of Gaunt’s lament for the leased out land, Jaques’ concern for the deer, the famine in Tarsus in Pericles. These passages are productive for ecocritical readings by scholars and students who can slow down to parse them, understand them, and research their historical contexts. But when performed in early modern English surrounded by the plays’ many other words, the ecological language of Shakespeare is limited in its power to inspire ecological thinking and action (see Minton, Reference Minton and Gray2021). It is for this reason that we believe these texts need some adaptation, and have found it useful to:

1) Cut plays so that what matters most to the plot and the production’s aims remains, and confusing and offensive material is addressed, reframed, or excised

2) Bring a play’s ecological language forward and work with actors to reinterpret passages so that they speak to our contemporary environmental and social moment

3) Import language from other Shakespearean plays and early modern texts

4) Adapt or translate language to be accessible and comprehensible to audiences

Don’t panic. Shakespeare will be fine, no matter what we do to his plays. They cannot be exhausted for future generations, but they can be infinitely adapted to portray the challenges faced by our many fragile oikoi (homes).

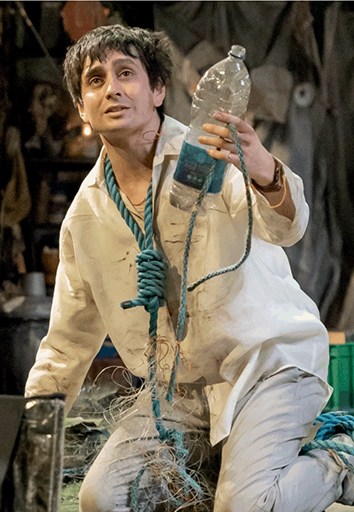

These plays are not without problems, not without language that is misogynist, racist, heteronormative, and even anti-ecological. Indigenous American theatre-maker Madeline Sayet reminds us that ‘within Shakespeare’s plays, we find both rationality and understanding of the natural world’s connectedness to our behaviour and colonial ideas that move us toward a destructive, extractive world’. She reminds us that theatre-makers get to choose what to do with these plays and ‘we must return our thinking to the circle, instead of being extractive with Shakespeare’ (2021). Returning our thinking to the circle means highlighting when Shakespeare’s plays engage with the more-than-human world: when Titania’s enchantment with Bottom ‘evokes the most benign possibilities for humanity’s engagement with nature’ (Watson, Reference Watson, Bruckner and Brayton2011: 45), when Hamlet ‘explores the thin line that separates the human from its imagined primate original’ (Dionne, Reference Dionne and Gajowski2020: 316), or when the plays are simply what Alys Daroy calls ‘biophilic’ and celebrate the wonder of the natural world (2022). We also want to theatrically emphasize moments of cooperation and forgiveness that model the kinds of behaviour needed to mitigate and make more equitable the crises facing our communities. Because such moments can be found across genres, we both find ourselves importing lines from other plays: bits of Troilus and Cressida, Richard II, Hamlet, and The Tempest found their way into the 2018 and 2024 productions of Dream for Shakespeare in Yosemite, and Elizabeth’s 2023 Tempest for the RSC borrowed from the sonnets and Dream (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Alex Kingston as Prospero, The Tempest, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, 2023.

Cutting away what is not relevant to a production’s ecological goals and primary storytelling can allow Shakespeare’s language, when paired with clearly focused acting, to make new ecological meanings (see also Brokaw and Prescott, Reference Brokaw, Prescott, Henderson and O’Neill2022). For most spectators who see a Shakespearean play performed in English (and here translated, non-Anglophone Shakespeare has an advantage!), most of what they are hearing is somewhere between mildly baffling to utterly incomprehensible. That is no one’s fault: Shakespeare’s plays are well over 400 years old, and next to no one living in the twenty-first century, be they a native English speaker or not, can fully comprehend them when listening to them, unglossed and at speed. However, when it comes to effective eco-theatre, it is crucial that audiences understand what they are hearing.

With most spectators, theatre-makers don’t win points for being faithful to Shakespeare’s language, but they lose points for being incomprehensible, for making audiences feel stupid and excluded. We therefore want to inspire eco-theatre-makers (and all theatre-makers) to adapt and translate Shakespeare’s language when it helps audiences feel included in the story, and therefore included in environmental crises and solutions. That might mean changing ‘thou dost’ to ‘you do’, ‘exempt from public haunt’ to ‘outside the busy town’, or indigenizing references to place, flora, and fauna to refer to the community and ecosystem in which a play is being performed. Shakespeare is super dead: he won’t care.

2.4 Adapting beyond Shakespeare’s Language

Shakespearean texts give us a lot of effective raw material for creating eco-theatre: descriptive ecological language, stories of power struggle and cooperation, multilocational plotlines. But because these plays are out of copyright, theatre-makers need not limit themselves to working only with Shakespeare’s language (including translated and adapted language). When it suits their intellectual, emotional, and social goals, theatre-makers should feel free to:

1) Collaborate with non-Shakespeareans – activists, frontline community members, scientists – to best adapt the script

2) Rewrite the text to make it more clearly evoke particular ecosystems, communities, and environmental crises and solutions

3) Write new lines that convey environmental storylines and information

4) Use music and dance to enhance feelings of grief, hope, and solidarity

The goal here is to help preserve life on Earth, not resuscitate Shakespeare, and theatre-makers should do whatever is needed to create the most effective eco-theatrical experience. In rewriting old stories to address the various crises of our world, we are doing what Shakespeare did for early modern England.

While there is much to be gained from reading ecocritical scholarship and turning to Shakespeare’s texts for inspiration, we have found that it is also important to collaborate with non-Shakespeareans whose expertise and life experiences can inform our productions. Katie’s team includes scientists and park rangers whose work on red-legged frogs, forest fires, and giant sequoias is central to Shakespeare in Yosemite’s productions; Elizabeth consulted with the Recycled Orchestra of Cateura in Paraguay, the UK Woodland Trust, and other global and local environmental organizations. Working with experts and people with firsthand experience of environmental catastrophe allows us to adapt and perform texts that are more truthfully rooted in particular communities near and far, evoking the challenges of our living world rather than Shakespeare’s long lost past. An audience member needs to mourn more than the deforestation of Shakespeare’s forest of Arden, feel wonder beyond the fairy Peaseblossom: ideally, they think of threats to their own most beloved landscapes, awe at creatures in their backyard.

Adaptation of language can do some of this collapsing of real and imaginative worlds. From a stage surrounded by trees, Shakespeare in Yosemite’s Juliet gazed at what she was describing when she exclaimed ‘that which we call a ponderosa pine by any other name would smell as sweet!’ (see Figure 4). But that production, being about the reintroduction of the near-extinct red-legged frogs to the Sierra ecosystem and not about teen suicide, was also full of language that Katie and her park ranger collaborators invented wholesale. Some of it was borrowed from Shakespeare (‘when it comes to biodiversity loss, all are punished’). Some of it was not. The production’s goals guided all textual choices: the team was more loyal to the living creatures of 2023 than to the memory of Shakespeare.

Figure 4 Madelyn Lara as Juliet, Romeo and Juliet in Yosemite, Yosemite National Park, 2023.

In South Africa, the Joburg Theatre Youth Development Programme’s production of Macbeth (2021) employed adaptive ecodramaturgy to decolonize the play. The numerous bird species that Shakespeare names, often for their familiar symbolic associations in Europe, were found to resist relatable decoding in the South African context. Director Sarah Roberts describes how the ensemble found that Banquo’s comment on the curious phenomenon of a nesting martlet as he approaches Glamis castle ‘lacked purchase for a local audience’ and only seemed to ‘stress distances between the play and a South African audience’ (2022: 6). The lines were cut, re-coded, and replaced by avian references that allowed the multi-lingual company – who performed the play in English, Zulu, Xhosa and Sesotho as well as other languages – to ‘render the text without alienating listeners or undercutting the value of local, experiential knowledge’ (ibid.: 6–7).

While adapted and newly scripted words can go a long way towards moving an audience towards theatre-makers’ intellectual, emotional, and social aims, use of music and dance can further them even more. In a book on what he calls ‘ecomusicology’, Mark Pedelty quotes several people describing how specific songs spurred them to environmental action and informed them of things they didn’t know about; ‘clearly, musical knowledge can translate into action’ (Reference Pedelty2012, 61). Pedelty ultimately concludes that music is more ecologically inspiring when yoked to other artforms: ‘Ecomusicology needs to look toward music’s intertextual connections. Music becomes even more meaningful when joined with other arts, media, and activities’ (204). We have found through both practice and study that music joined with Shakespearean theatre can be a catalysing conveyer of ecological messaging, as can other extra-Shakespearean elements.