1 Introduction

1.1 “For Europeans, the World Is Round”

In one of his lectures on the Philosophy of History at the University of Berlin during the winter term of 1822/1823, Hegel explained to his students how he viewed the position of modern Europe within the broader context of world history. For him, European societies are underpinned by a universalist understanding of freedom deriving from Christianity: not only one tyrant or some privileged citizens, but all humans as such are entitled to live in freedom. Insofar as such freedom is realised in the institutions of modern European societies, history has come to an end: “Up to now, the periods [of world history] involved relating to an earlier and a later world-historical people. But now, with the Christian religion, the principle of the world is complete; the day of judgment has dawned for it”.Footnote 1

This means not only that no further world-historical period is to be expected after that of modern Europe but also that nothing in the contemporary world really lies outside of modern Europe:

The Christian world, as this completion in itself, can have a link to the outside world only in a relative manner, and the point of this relationship is merely to make it manifest that the outside world is intrinsically overcome. … The Christian world has circumnavigated the globe, dominates it[.] <For Europeans, the world is round, and what is not yet dominated is either not worth the effort or yet destined to be dominated.>Footnote 2

At a purely descriptive level, Hegel has a point: European colonialism – the conquest, settlement, and exploitation of overseas territories undertaken by many European countries between the fifteenth and twentieth centuries – was indeed a global phenomenon. When Hegel was born in 1770, large parts of the Americas, as well as significant territories in Africa and Asia (including large areas such as the Cape Colony, British Bengal, and the Dutch East Indies), were under the rule of Spain, Portugal, Britain, France, the Netherlands, and Denmark. By the time Hegel was giving his lectures, the USA (1783), Haiti (1804), Mexico (1810), Argentina (1810), Brazil (1822), and most other parts of Latin America had won independence. Still, except for Haiti, these countries would remain dominated by their white European-descended populations, and some would maintain slavery for decades to come (the USA until 1865, Brazil until 1888). Moreover, three further waves of European colonisation were underway during Hegel’s lifetime: in Australasia, where the first British colony in Australia was established in 1788; in Africa, where the French invaded Algiers in 1830 and used it as a basis for conquering the inner parts of Algeria, anticipating the later Scramble for Africa; and in Asia, where the British East India Company was expanding its control over the entire Indian subcontinent, Napoleon tried to turn Egypt into a French colony (Campaign in Egypt and Syria, 1798–1801), and Britain responded by extending its colonial ambitions to Central Asia and the Middle East.

Yet, in the passage from the lectures on the Philosophy of History Hegel does not merely point to the global and expansive nature of European colonialism. He also presents colonial rule and expansion as inevitable destiny and even celebrates colonialism as a world-historical process that has brought the world closer to its goal. This is appalling but also puzzling. If freedom is a universal entitlement of all human beings, according to the conception that Hegel approvingly ascribes to Christianity, how can he see anything but a complete historical disaster in the fact that, for several centuries, Europeans brought violent death, lasting oppression and exploitation, forced labour, land theft, and cultural destruction to countless people all over the world, and the forced embarcation on slave ships to more than 10.6 million Africans (counting only the documented casesFootnote 3)? Why would Hegel not instead follow the example of others such as Diderot, Kant, and HerderFootnote 4 and develop a philosophical critique of colonialism? If Hegel indeed thinks that being ruled by Europeans is the ‘destiny’ of non-European people, how does this influence his ongoing relevance to social and political philosophy, where his thought remains a subject of significant exegetical and theoretical interest?

To answer such questions, it is necessary to better understand Hegel’s views about European colonialism, which is the undertaking of this Element.

1.2 Debating Hegel’s Views on Colonialism

Much of the existing literature on Hegel’s views about colonialism focuses on his treatment of “colonisation” in §248 of Elements of the Philosophy of Right. After discussing maritime trade in the previous section, Hegel goes on to argue as follows: “This extended link also supplies the means necessary for colonisation – whether sporadic or systematic – to which the fully developed civil society is driven, and by which it provides part of its population with a return to the family principle in a new country, and itself with a new market and sphere of industrial activity”.Footnote 5

As becomes more apparent from lecture transcripts, “systematic” colonisation is driven and controlled by the metropolitan government and has the advantage that the colonisers remain connected to the metropole (presumably, Hegel has trade and taxes in mind). “Sporadic” colonisation lacks this advantage since it occurs when individuals migrate to a foreign colony.Footnote 6 The “fully developed civil society” is “driven” to colonisation because, without state regulation, overproduction crises create poverty: contingent fluctuations in demand can easily result in overproduction, leading to excess labour supply in a given sector. As it is difficult for specialised labourers to switch professions, such imbalances can lead to unemployment, the central cause of poverty in civil society.Footnote 7 Hegel thinks that when unemployment and poverty become widespread in civil society, colonies can serve as economic and social safety valves, as they allow impoverished citizens to acquire land for agriculture and create new markets for the metropole. (He formulates these points as general observations, but his listeners would have linked them to ongoing debates about German emigration. A particularly massive emigration wave following the famine in 1816 – the ‘year without a summer’ – aroused political interest in emigration as a social question, including a proposal by Bundestag delegate Hans von Gagern in favour of state-organised emigration and colonial settlements.Footnote 8)

Commentators disagree whether Hegel’s account of colonisation in PhR §248 and related texts is (a) merely descriptive,Footnote 9 or whether it also contains an evaluation. In the latter case, some hold that Hegel’s comments are (b) in support of colonisation – recommending it as a remedy for overpopulation and overproduction,Footnote 10 and thus taking a stance in an ongoing debate about the economic and social utility of the colonies which involved thinkers like Smith, Steuart, Sismondi, and Malthus.Footnote 11 Others – especially authors reading Hegel as a proto-Marxist critic of capitalism – think that PhR §248 is (c) critical of colonialism: by interpreting it as a necessary consequence of civil society, Hegel meant to criticise the latter.Footnote 12

While we find it hard to see how the relevant texts support reading (c), we do not aim to decide here between the different readings of PhR §248. As part of Hegel’s theory of civil society, the account of colonisation in PhR §248 and related texts is formulated from a methodological viewpoint that, much like the contemporary economic debate on colonialism, is exclusively concerned with the domestic social and economic order. Questions about the place of European colonialism in global history and how colonial enterprises relate to the interests and rights of the colonised are irrelevant to that perspective. But this does not mean that Hegel did not address questions of the latter kind, too. We only need to turn to other parts of Hegel’s mature system to find texts relevant to the normative and historical assessment of European colonialism. These include the accounts of international law and world history in the Elements of the Philosophy of Right (or Philosophy of Right, for short) and Encyclopedia; the discussions on non-European continents and their inhabitants in the lectures on the Philosophy of History and the Philosophy of Subjective Spirit; and the treatment of slavery in the Philosophy of Right and various lectures.

In this study, we will focus on these latter aspects: Hegel’s normative and historical assessment of European colonialism in its relationship to the colonised groups. In doing so, we build on the work of several scholars who have explored Hegel’s views about colonialism beyond the economic account in PhR §248.Footnote 13 Authors like Serequeberhan (Reference Serequeberhan1989), Dussel (Reference Dussel1995), Guha (Reference Guha2003), Pradella (Reference Pradella2014), and Habib (Reference 68Habib2017) have pointed to the importance of Hegel’s account of world history in PhR §§341–360, and in particular of his notion of an “absolute right” in PhR §§347 and 350, for the issue of colonialism (cf. Section 5). Others have focused on Hegel’s relation to transatlantic slaveryFootnote 14 and his views about the colonisation of the Americas.Footnote 15 In her influential 2020 article “Hegel and Colonialism”, Alison Stone examines how pro-colonialist and pro-slavery strands in Hegel’s texts are systematically connected with his theory of freedom – and hence, with a part of his thought that is usually seen as both central to his system, and of continued philosophical interest.

All these authors approach Hegel through a critical lens. They seek a better understanding of elements in Hegel’s philosophy that they see as favouring European colonialism and, therefore, as profoundly mistaken. Others have taken a more apologetic stance. Thus, Timothy Brennan reads Hegel as a thinker who challenged Enlightenment Eurocentrism,Footnote 16 and whose analysis of civil society entails the illegitimacy of slavery.Footnote 17 In response to apparently racist and pro-slavery statements, Brennan points to philological issuesFootnote 18 and the prejudices of Hegel’s time.Footnote 19

Hence, Hegel’s views about colonialism have received a fair amount of scholarly attention, and there are different views about his normative stance on colonialism. But much of this discussion has proceeded piecemeal, interrogating quite limited selections of his texts. What is missing from the literature – and what we aim to provide in this Element – is a systematic interpretation that examines and contextualises the various discussions of colonial phenomena found in Hegel’s mature texts. We reconstruct his accounts of topics like the extermination of peoples and cultures in the Americas, American societies during and after colonial rule, Jesuit missions, transatlantic slavery and its abolition, and British rule in India. We connect these accounts to relevant debates in Hegel’s time and his own underlying philosophical views on issues like person- and statehood, the dialectic of lordship and bondage, and the nature of world history.

Methodologically, we thus fully embrace Stone’s emphasis on the systematic connections between Hegel’s views on colonialism and other, including more popular, parts of his thought, and we agree with Brennan that it is important to contextualise Hegel in the intellectual climate of his time. We also share Brennan’s concern for philological issues (cf. Section 1.6). Yet, as will become apparent throughout this Element, we have found that scrutiny of Hegel’s critically edited texts in their historical and systematic context yields a picture in which he develops philosophical justifications for colonial conquest and rule and even for transatlantic slavery, as a means for promoting the realisation of freedom on a global scale – necessary means, Hegel thinks, because the autonomous development of non-European groups is limited by alleged racial characteristics (cf. Section 1.4).

We do not wish to deny that Hegel’s oeuvre may nevertheless be a fruitful resource for contemporary philosophy, including anti-racist and anti-colonial thought (cf. Section 6.3). But we do think that there is an urgent need for Hegel scholarship and neo-Hegelian thought to examine how Hegel’s views on such topics as freedom, history, agency, personhood, and the dialectic of lordship and bondage are entangled with his positions on issues like colonial rule, race, and transatlantic slavery. If these entanglements are overlooked, and Hegel’s philosophy is discussed as if it were unrelated to issues like hierarchical views of race, colonialism, and transatlantic slavery – or even fundamentally opposed to themFootnote 20 – we risk inheriting Hegel’s mistakes while adopting his insights.

But is looking for a conception of colonialism in Hegel’s texts even legitimate? Why should he have taken much notice of, or had more than very superficial knowledge about, other European countries’ colonies in remote parts of the globe? Before examining his views on this topic, we must clarify Hegel’s epistemic position vis-à-vis colonialism.

1.3 Colonial Echoes in Germany

The German-speaking countries had no overseas territories of their own during Hegel’s lifetime, after Brandenburg-Prussia had sold in 1721 the last of its possessions on the African West coast (one of which Hegel mentions in a lectureFootnote 21) and before Germany began to conquer its colonial empire in 1884. Still, the colonies were not far from people’s minds in Hegel’s Germany. German novels and dramas of the time, as well as popular travelogues, contributed to creating a colonial imaginary.Footnote 22 German readers had every reason to follow the coverage in newspapers and magazinesFootnote 23 of the American wars of independence, the Haitian Revolution, and ongoing manoeuvres of colonial expansion, as they were crucial for relations among European nations. Earlier periods of colonial history were covered in school and university teaching and popular literature; Hegel could find accounts of the cruelty of the Spanish conquest of South America in the textbook on universal history by Johann Matthias Schröckh that he praises in an early diary entryFootnote 24 as well as in Joachim Heinrich Campe’s Die Entdeckung von Amerika (3 vols., 1781 f.), a youth book that he cites as a student.Footnote 25

There were also academic and public controversies in Germany that pertained to colonialism. Philosophers like Kant and Herder followed in the footsteps of Enlightenment authors abroad, such as Diderot, and argued against the legitimacy of colonial conquest.Footnote 26 Others suggested already in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries – also in the context of the debates on emigration mentioned in Section 1.2 – that German countries should again have colonies.Footnote 27 German abolitionists such as Matthias Christian Sprengel and Therese Huber translated and published contributions from the French and British debates on the abolition of the slave trade – in the case of Huber in a newspaper, the Morgenblatt für gebildete Stände, which Hegel read at least during some periods of his life.Footnote 28 Controversies surrounded early ‘scientific’ versions of hierarchical views on race, which were proposed by authors like Kant and Christoph Meiners, opposed by others such as Herder and Georg Forster, and explicitly used by Meiners to defend colonial slavery.Footnote 29 Hegel owned a copy of Meiners’s 1785 Grundriß der Geschichte der Menschheit, which includes a summary of Meiners’s theory of race. He was likely familiar with Forster’s and Herder’s critiques as well: he refers to a text in which Forster explicitly criticises hierarchical views of race,Footnote 30 and in his copy of the 1817 Encyclopedia, he noted excerpts from the very parts of Ideas for a Philosophy of the History of Mankind where Herder rejects the race concept.Footnote 31

Besides, Hegel regularly read British periodicals – Morning Chronicle, Edinburgh Review, and Quarterly Review – that reported on topics such as the abolition debatesFootnote 32 and the discussions on India, and he was familiar with various British and French books that discussed colonialism in detail. As a private teacher in Switzerland, he studied the monumental Histoire des deux Indes (1770),Footnote 33 a comprehensive, multivolume account of the past and present of European colonialism, edited by the Abbé Raynal and co-authored by Diderot.Footnote 34 In the same period, Hegel studied works by Scottish Enlightenment authors such as Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, and James Steuart, which, too, contained detailed discussions of topics like colonial economy and slaveryFootnote 35 – as did the works of British and French national economists whom he read later on, e.g., Sismondi.Footnote 36 As we shall argue in Section 3, Hegel was even familiar with a major work on slavery and the slave trade by a British abolitionist. Finally, Hegel closely followed the then-emerging orientalist literature.Footnote 37 Such literature contained not only scholarship on the ancient Asian cultures but also racial commentary on the contemporary mores in those countries and information about colonial rule.

Hegel apparently was quite eager to use sources like these to keep himself informed about what he himself regularly referred to as the “colonies” or “colonisation”. As we will see in Sections 2 to 4, he offers fairly detailed comments and discussions about colonialism and its aftermath in the Americas, transatlantic slavery, and India under Company rule. He was also aware of further (neo)colonial activities of European powers around the globe: he mentions British trade representations in South America,Footnote 38 which were part of an attempt to develop hegemony over newly independent countries like Argentina; Lord Elphinstone’s mission to Afghanistan (1808/1809),Footnote 39 which prepared British expansion in Central Asia; and British settlements in Australia.Footnote 40 Michelet’s edition of the lectures on the Philosophy of History reports both a prediction that Europeans would eventually colonise also China,Footnote 41 and a (seemingly endorsing) reference to the 1830 conquest of Algiers mentioned in Section 1.1.Footnote 42 The Hegelian corpus thus echoes all the major colonial developments in Hegel’s lifetimes invoked in Section 1.1.

1.4 Hegel on European Colonialism as Racial Domination

Not only was Hegel very much aware of the history and present state of European colonialism, but arguably also viewed it as distinct from ancient colonisation. As will emerge in the course of this Element, his discussions are held together by an implicit conception that identifies a fundamental characteristic of European colonialism, namely, its character as racial domination. European rule over the Americas, the enslavement of Africans, and British rule in India are all described by Hegel as forms of violence and domination that one racial group, Europeans, exercises over other racial groups.Footnote 43 For Hegel, these various colonial regimes are assessed in terms of a ‘liberating’ or ‘civilising’ function (cf. Section 5), and this function depends for its efficacy on forms of domination that are ‘adequate’ to the racial characteristics Hegel ascribes to the colonised.

By connecting colonial rule to race, this implicit conception captures a crucial feature which indeed sets apart modern European from ancient colonialism: the massive extent to which it was linked to processes of racialisation and corresponding racist ideologies. Yet, at the same time, Hegel arguably fully endorses the pro-colonialist implications and racist underpinnings of this modern form of colonialism. Indeed, as will become clear throughout this Element, Hegel’s discussions of colonialism rely at crucial junctures on his own hierarchical account of race. We have elsewhere reconstructed this account as an application of basic notions from Hegel’s metaphysics to the phenomenon of human diversity:Footnote 44 Hegel considers it metaphysically necessary that human spirit is realised, at least temporarily, through different, group-specific, and geographically located levels of mental ability. These levels range from a mere capacity – which he ascribes to people of African originFootnote 45 – for being taught abstract thought and rational behaviour by others, to a limited form of intelligence that he assigns to Asians,Footnote 46 and finally, to the fully rational cognitive and volitional abilities he claims for Europeans.Footnote 47 The Indigenous peoples of America and Oceania are seen as a contingent addition to this scheme, with Americans ranking even lower than Africans.Footnote 48 Importantly, Hegel considers these racial characteristics to be hereditary,Footnote 49 but not unchangeable. Instead, he speculates that acquired traits can gradually become innateFootnote 50 – an assumption that, as we will see, undergirds Hegel’s contention that colonialism and slavery gradually ‘educate’ racial groups who had hitherto been considered mentally inferior to Europeans.

1.5 Overview of the Following Sections

Sections 2–4 examine Hegel’s comments on concrete forms of colonial regimes in the Americas and India. Section 2 addresses the colonial and postcolonial Americas, focusing on four central topics in Hegel’s discussions: differences between the British colonisation of North America and the Spanish colonisation of Latin America; the mass killings and cultural destruction of Indigenous American people; the structure of colonial and postcolonial societies in Britain’s Thirteen Colonies/the USA and Spanish America; and the Jesuit missions in Latin America, the so-called ‘reductions’.

In Section 3, we turn to transatlantic slavery. Taking our cue from a section in Hegel’s Philosophy of Right that presents views for and against the legitimacy of slavery as forming an “antinomy”, we uncover the hitherto ignored connections of this text to the contemporary abolitionist debate in Great Britain. We locate Hegel’s own discussion of slavery and abolition in the context of this debate and reconstruct the philosophical basis of Hegel’s qualified justification of slavery in his theory of personhood and property and the dialectic of lordship and bondage.

In Section 4, we discuss Hegel’s comments on British rule in India. By interpreting Hegel’s remarks against the background of his sources and the contemporary British debates about colonial policy in India, we argue that Hegel favours the East Indian Company’s initial attitude of (strategically motivated) toleration vis-à-vis traditional Indian cultures and societies against those who were campaigning for a more assimilationist approach. Unlike in the cases of Americans and Africans, Hegel does ascribe, in our reading, personhood and rights to people in India. Nevertheless, he has no objections to British rule and even explicitly postulates a civilising mission of the British.

In Section 5, we explore the normative framework that allows Hegel to legitimise not only the colonisation of America and the enslavement of Africans but also colonial rule in the cases where his theory of race yields slightly less derogatory results, such as India. To do so, we offer a reading of Hegel’s comments on the “absolute right of the Idea” in the final part of the Philosophy of Right. We identify a hitherto neglected background to this notion in the Scottish Enlightenment, particularly its ‘four-stages theories’ of social development. This context enables us to argue that Hegel’s account of the “absolute right” carries pro-colonial implications and serves to justify European rule in Asia, too.

Section 6 concludes by putting Hegel’s discussions of colonialism into broader historical perspective. After locating Hegel vis-à-vis Enlightenment critiques of colonialism and emerging liberal imperialism, we offer a brief overview of his deeply ambivalent legacy in matters of colonialism and slavery.

In his discussions of colonialism, race, and ethnicity, Hegel orders immensely complex human, cultural and historical realities along highly generic lines of division, grouping together the inhabitants and societies of entire continents under artificial labels defined by prejudiced ‘characteristics’. This style of thinking is itself a typical feature of colonial discourse and Enlightenment racism.Footnote 51 As we are reconstructing Hegel’s discussions on colonialism, our exposition follows the way he divides phenomena; however, we ask readers to bear in mind that we do not thereby endorse those divisions, let alone the labels he attaches to them.

1.6 A Note on the Texts

Hegel’s most detailed discussions of the European colonies are found in lectures on the Philosophy of History, Subjective Spirit and Right he gave during his time in Berlin (1818–1831). Most older editions of these lectures, still widely used in Hegel scholarship, are philologically opaque compilations of various transcripts and manuscripts. Meanwhile, the extant transcripts have been published in critical editions in the authoritative academy edition, Gesammelte Werke (GW). In this Element, we use GW as the principal source for the lectures.Footnote 52 Many of these transcripts remain untranslated. Where transcripts coincide with the text in older editions of which there are translations, we use those; where no translation is available, we provide our own.

2 Hegel and Colonialism in the Americas

2.1 The Violence of Colonisation

An important part of traditional colonial discourse consists in the notion that the colonisation of North America, especially when undertaken by the British, essentially differed from how Latin, and particularly Spanish, America was colonised. On this account, which has its roots in the anti-Spanish ‘Black Legend’ of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,Footnote 53 Spanish colonisation took the form of conquest, marked by brutality, mass murder (as documented in early reports by authors like Bartolomé de las Casas),Footnote 54 and the subjugation of Indigenous populations to the Spanish crown, and driven by motives such as greed for silver and gold, a lust for domination or ‘spirit of conquest’,Footnote 55 as well as Catholic fanaticism.Footnote 56 By contrast, British colonisation was depicted as a largely peaceful process of settlement between Indigenous territories, driven by meaningful purposes such as agriculture and commerce. This process created new settler societies, characterised by protestant tolerance, alongside independent Indigenous nations,Footnote 57 and was beneficial for the native Americans, too.Footnote 58

While of limited historical accuracy – British colonisation, too, involved warfare, a mentality of conquest and lust for richesFootnote 59 – this account was politically convenient for Britain and became hugely influential.Footnote 60 Hegel could read versions of it in various authors he was familiar withFootnote 61 and adopted it himself when structuring the discussions of the Americas in his courses on the Philosophy of History around the contrast between Spanish colonies in South America and British colonies in North America.Footnote 62 (Like his account of Africa, he relegates these discussions to the introductory part on the “geographical basis of world history”, as he thought Indigenous Americans and Africans had never entered world history; cf. Section 3.4.) Hegel points out that the Spanish “have conquered South America in order to rule, in order to get rich”.Footnote 63 North America, by contrast, has been “populated” (bevölkert)Footnote 64 by Europeans who settled in the “neighbourhood” of Indigenous people,Footnote 65 bought land from them, and assigned new territories to them; warfare was used only by Indigenous groups in their conflicts with each other.Footnote 66

Hegel’s comments on the American colonies thus echo long-standing ideological notions. Yet, against this foil, it is also possible to identify more original views in his discussions. In particular, his comments on the mass killings of Indigenous populations and the destruction of their cultures cut across the traditional contrast between Spanish conquest and British settlement. While that tradition acknowledges such violence only in the case of the conquistadores, Hegel stresses that the colonisation of North America, too, has had an enormous human toll. The peoples of North America, he tells his students, have “gradually vanished”:Footnote 67 “The original inhabitants have been as good as annihilated by the immigrants and only continue to exist in small tribes”.Footnote 68

Rather than blaming the colonisers for their violence, however, Hegel tends to mystify that violence and depict it as a spontaneous process, an automatic decline and “disappearance” of American peoples due to their mere spatial vicinity to the European colonisers: “In the contact with more educated peoples, with more intense education, these weakly educated peoples have disappeared”.Footnote 69 In the case of the British colonies in North America, he even talks about a “wondrously annihilating effect” that the mere “neighbourship of the Europeans” had upon them.Footnote 70 Indigenous peoples were, he contends, “attacked by the alien European culture as by a poison and overcome by it”.Footnote 71

Hegel uses the same rhetoric when it comes to the cultural impact of colonialism. He explicitly acknowledges that European colonisation destroyed Indigenous cultures: “the conquest was the ruin of this [American] culture”.Footnote 72 “Mexico and Peru”, he points out, “had reached the most significant levels of culture”.Footnote 73 Yet, these and other American cultures could not resist the Europeans: “The old American world has disappeared”.Footnote 74

Hegel is well aware that all this did not occur magically but had concrete causes: he points to the technological and military inferiority of Indigenous Americans – their lack of “horse and iron”Footnote 75 – as well as the introduction of liquor in North America and the role of imported diseases.Footnote 76 But why does Hegel then foreground the picture of a process of ‘disappearing’, rhetorically downplaying the agency of the colonisers who were responsible for large-scale cultural and biological extermination?

The reason for this can be found in his views about the geographic and racial characteristics of the Americas and their Indigenous inhabitants. Building on a strand of colonial discourse that goes back to Buffon and includes seminal works like de Pauw’s Recherches philosophiques sur les Américains (1768) and the Histoire des deux Indes (1770),Footnote 77 Hegel thinks the New World is generally defined by weakness and immaturity – a “young, weak country”.Footnote 78 Not only are New World animals smaller and weaker than their Old World counterparts,Footnote 79 but humans, too, are of a “weaker species” [Geschlecht]Footnote 80 in America. This “inferiority” is not only a matter of physical constitution – e.g., small body size – but also of “spiritual”, i.e., psychological and cultural, characteristics.Footnote 81 Thus, Indigenous Americans, Hegel thinks, display a “mild and passionless disposition, want of spirit, and a crouching submissiveness toward a Creole, and still more toward a European”.Footnote 82 Similarly, traditional culture in the Americas, including that of the Incas, Mayas, and Aztecs, was “of a feebler stock”.Footnote 83 Indeed, the lack of horses and iron among Americans is itself an expression of this characteristic American weakness.Footnote 84

Hence, Hegel’s choice of the terms in which he depicts biological and cultural mass destruction in the colonial Americas suggests that these phenomena were a direct consequence, not so much of the aggressiveness of the Europeans but of the typically American weakness that fundamentally characterises life – organic, mental, and cultural – in the New World. Hegel does not explicitly evaluate the extermination of Indigenous cultures and populations, but this silence is in itself telling, given not only how common it was in writings of his time to denounce the lethal side of colonialism, at least in South America, but also that he elsewhere in the lectures on the Philosophy of History does seem to voice his disapproval of reported instances of ethnic killingFootnote 85 and the desecration of local religious symbols.Footnote 86

Overall, Hegel’s comments convey an account of colonial extermination in the Americas that can be seen as inverting a crucial element of the Black Legend. The latter sees colonial violence on the part of the conquistadores as an expression of negative racial features ascribed to the perpetrators as Spaniards (due to their partially Islamic heritage, the Black Legend treats Spanish people as Black and African).Footnote 87 For Hegel, by contrast, such violence responds to the negative racial features he ascribes to the victims qua Indigenous Americans. As we will see throughout this Element, the notion that determinate forms of colonial violence match or are ‘appropriate’ to the alleged racial features of particular groups is a guiding thread in Hegel’s views on colonialism.

2.2 American (Post)Colonial Societies

Besides the exterminatory effects of conquest and settlement, Hegel discusses the structure and development of colonial societies in the Americas, including the recent and ongoing independence processes. In the case of the Thirteen Colonies/USA, Hegel paints, consistently with the traditional account, a rather rosy picture of settlers who draw on the “treasure of European culture”Footnote 88 and the ethos of ProtestantismFootnote 89 in their ongoing efforts of expansionFootnote 90 and development of agriculture, trade, and commerce.Footnote 91 The fact that the settlers have not yet reached the boundaries of the continent means that as soon as social inequality and “discontent”Footnote 92 arise among them, the remedy of further expansion is always available. Consequently, the formation of a proper civil society in the USA – including social stratification, urbanisation, and industrialisationFootnote 93 – is still in its beginnings. Hence, there is not yet a felt “necessity for a firm combination”,Footnote 94 for a robust political organisation, either. The present republican constitution of the USA only serves to protect the safety and private property of the settlersFootnote 95 and thus is, by Hegel’s light, a mere “state of necessity and the understanding”.Footnote 96 Further social development will make it necessary to create a more robust and organic state, perhaps a monarchy.Footnote 97

Hegel thus can be seen as extrapolating the traditional, positive account of British colonisation into a narrative of the Thirteen Colonies/USA as a (post)colonial success story – failing almost entirely to consider what challenges the ongoing oppression of Afrodiasporic and Indigenous groups might create for the development towards an ‘organic’ society. He was well aware that “the Southern states are based on slavery” and dominated by the planter aristocracy (“nobility”),Footnote 98 knew about ongoing debates on abolition in the USA,Footnote 99 and echoes contemporary debates in the USAFootnote 100 by pointing out that the contrast between the slave economy of the South and the Northern states holds the potential for a civil war.Footnote 101 Still, he interprets even this as merely an issue of conflicting “interests”Footnote 102 among different groups of whites.

Hegel is much more attentive to intrinsic problems of (post)colonial societies in the case of Spanish America.Footnote 103 The Spanish colonies, he points out, stood under the twofold yoke of political despotism and the “spiritual oppression” of Catholicism.Footnote 104 Here, a society defined by race and class hierarchies emerged, where “the people” were oppressed by secular and ecclesiastic elites (“higher classes”),Footnote 105 and Indigenous Americans were dominated by Spanish-born people and a mixed-race population of “creoles” – “a mixture of European and American or African blood”,Footnote 106 who “set the tone” in Latin America.Footnote 107

Interestingly, Hegel identifies several elements that stabilise the hierarchy of colonial society, leading to a “fixed social order”Footnote 108 that resists ongoing emancipatory struggles. The first is an undue emphasis on social distinction; people are driven by “ambition” and “thirst after orders and titles”.Footnote 109 They are, therefore, submissive towards those who can bestow the desired social status – the result being a general “spirit of servitude”.Footnote 110 At least in the case of Spanish and Creole groups,Footnote 111 Hegel seems to consider the “spirit of servitude” a product of colonial society; it is opposed to the “noble, free” character he ascribes to the inhabitants of the metropole.Footnote 112 A second stabilising feature is Catholic “superstition”, specifically the use of religious belief to defend the existing order.Footnote 113 As an illustration, Hegel mentions the Caracas earthquake in 1812, where the interpretation supplied by church authorities and Spanish royalists – a divine punishment for the independentist cause – created a drawback to the Venezuelan War for Independence.Footnote 114

Third, and most interestingly, Hegel also cites racial hostilities in this context: the Creoles, he points out, “lived in arrogance and contempt of the Indigenous Americans – and they all are in their turn subjected to the Spanish pride”.Footnote 115 The context of this passage – an account of a hierarchical social order in critical and pejorative terms – suggests that Hegel at least implicitly means to criticise such racist animus. This is remarkable, given that Hegel himself endorses a theory of race that massively denigrates non-European groups (cf. Section 1.4) and legitimises, as we will see, various forms of colonial domination. Hegel may rely here on a distinction similar to the contemporary one between ‘cognitive’ and ‘volitional’ forms or accounts of racism:Footnote 116 he may have thought that there is a difference between, on the one hand, what he framed as disinterested discussions about anthropology and colonial policy, and, on the other, overt racially motivated disdain or arrogance.Footnote 117 We will come back to related issues in Section 5.4.

In his remarks on the societies of Spanish America, Hegel thus identifies the “spirit of servitude”, Catholic ideology, and racist feelings as elements that contribute to the maintenance of a strict, race-based social hierarchy. Not only has this hierarchy retarded the process of independence, as in the case of the Caracas earthquake, but Hegel suggests that it also tends to destabilise the governments of the newly independent countries. He points out that the young Latin American republics “depend only on military force; their whole history is a continued revolution”.Footnote 118

This instability shows that the “spirit of true free self-consciousness”, the revolutionary spirit of the independentist movements which rebelled against the Spanish crown and the Spanish-born local elites, is “not sufficient to shake off the yoke” of Spanish domination; instead, a stable and free political order after colonialism would require “a proper education and instruction of the people”.Footnote 119 Hence, Hegel indicates the need for a social and cultural transformation in postcolonial Latin American societies, which presumably would have to dismantle the existing hierarchical order by addressing dominant patterns of social reward (“spirit of servitude”), religious irrationality, and racial animosity.

Among Hegel’s discussions of colonial phenomena, his remarks on South America stand out as they offer elements of a critical analysis of (post)colonial societies, which are informed by but also go beyond the traditional critique of Spanish colonialism mentioned in Section 2.1. However, despite Hegel’s attention to obstacles to the independence process in South America, he does not articulate an analysis of the revolutions in North and Latin America themselves; he shows no interest in their normative basis or the political processes driving them. Indeed, it is possible to hypothesise that these revolutions had no world-historical significance for him. What was important for world history was that Europe expanded its dominion over the globe (cf. the quotes opening Section 1). Since the American revolutions, as Hegel acknowledges in the case of South America, left intact the colonial social hierarchies, they did not really change the system of global European rule.

What Hegel’s assessment neglects, however, is that Indigenous American and Afrodiasporic people did play a part and pursue their own agenda in the revolutionary struggles. The North American Revolution saw hundreds of thousands of Black soldiers fighting for independence from Britain and numerous enslaved people gaining manumission. In Latin America, Indigenous people built on centuries-old traditions of anti-colonial resistance when participating in the wars of independence.Footnote 120 Despite their relevance for his account of world history, Hegel is not able to register such complexities because he postulates on racial grounds that (in the case of Latin America) only creoles, not Indigenous Americans, have been capable of reaching “the higher feeling of self, the upward-striving to autonomy, independence”.Footnote 121 Even where he is aware of a potential counter-example, such as the llaneros, nomadic riders with Indigenous roots who live in the Orinoco grasslands and played an important role in the Venezuelan War of Independence, he is quick to explain it away as a result of European influences: the llaneros owe their bravery to their horses, which come from Europe.Footnote 122

2.3 The Jesuit Reductions

Hegel’s views on the Indigenous inhabitants of South America are also deeply problematic when it comes to the question of how Europeans and their descendants should treat them. Rather than immediate freedom in a transformed postcolonial society, the “best thing that can be granted”Footnote 123 to Indigenous Americans consists, Hegel claims, in the particular form of colonial regime that Jesuits (and to a minor extent Franciscans) had established in their missions in the Rio de la Plata basin (especially among the Guarani in present-day Paraguay), Mexico, and California, known as ‘reductions’ (reducciónes).Footnote 124

The Jesuit reductions were settlements in which Jesuits lived together with Indigenous groups from surrounding areas, both to evangelise them and to protect them from slave raids. The first reductions were established in the early seventeenth century; they declined after the Jesuits were expelled from Spanish America in 1767. Hailed by some as utopian social experiments that used communal instead of private property and enabled Indigenous people to live in safety according to their own customs,Footnote 125 criticised by others as an oppressive ‘state within the state’ where Indigenous people were forced to work for the enrichment of the Jesuit order,Footnote 126 the reductions were much debated in eighteenth-century Europe and are alive in the memory of the European public in the early nineteenth century.Footnote 127 Hegel presents the reductions as highly paternalistic regimes (a “paternal government”)Footnote 128 that dictated virtually all details of adult Indigenous persons’ lives: They were forced to carry out agricultural work, the products of which were stored and distributed to cover the needs of subsistence.Footnote 129 The day was divided into labour and worship; bells were even rung at midnight to remind the inhabitants of sexual intercourse.Footnote 130

Hegel considers this the “best thing that can be granted” to Indigenous Americans because he sees a perfect match between the regime of the reductions and the racial characteristics of Indigenous Americans. On his account, the weakness that characterises Indigenous Americans (cf. Section 2.1) makes them devoid of any desires and drives,Footnote 131 and hence also incapable of providing even for the immediate future.Footnote 132 Instead, Hegel cites reports according to which they “live entirely for the moment, like animals”.Footnote 133 Thus, Hegel denies Indigenous Americans some of the most basic mental preconditions of human agency, arguing that by treating them like childrenFootnote 134 (and much worse), the Jesuits found the “most appropriate way” of assisting their development.Footnote 135

Hegel’s comments on the Jesuit reductions add an important side to his discussion of colonialism in South America. They make clear that Hegel’s notion of a social and cultural transformation in postcolonial South America is exclusionary, as it is not meant to apply to Indigenous groups, at least not at present. At the same time, Hegel’s account of the reductions is a further instance of how he sees specific forms of colonial violence as appropriate to the colonised groups’ racial characteristics – and hence his view of European colonialism as racial domination. We will again find this notion in the other forms of colonial regimes discussed in the following sections, beginning with an aspect of colonialism that connects the Americas to Africa: transatlantic slavery.

3 Hegel, Africa, and Transatlantic Slavery

3.1 The ‘Antinomy of Slavery’

Of all aspects of European colonialism, transatlantic slavery receives the most attention and philosophical elaboration from Hegel. He comments on it repeatedly when discussing Africa and its inhabitants in the lectures on the Philosophy of History and the Philosophy of Subjective Spirit. He also addresses this issue when he discusses the dialectic of lordship and bondage in his lectures on Subjective Spirit.Footnote 136 Yet arguably, Hegel’s most prominent discussion of transatlantic slavery is found in the section on Abstract Right within his 1821 Elements of the Philosophy of Right. In his long Remark to §57 in this Element, Hegel presents two opposite positions regarding slavery, which, he tells us, form an “antinomy”:

[Thesis] The alleged justification of slavery (with all its more specific explanations in terms of physical force, capture in time of war, the saving and preservation of life, sustenance, education, acts of benevolence, the slave’s own acquiescence, etc.), as well as the justification of lordship [Herrschaft] as simple domination [Herrenschaft] in general, and all historical views on the right of slavery and lordship, depend on regarding the human being simply as a natural being [Naturwesen] whose existence (of which the arbitrary will is also a part) is not in conformity with his concept.

[Antithesis] Conversely, the claim that slavery is absolutely contrary to right is firmly tied to the concept of the human being as spirit, as something free in itself, and is one-sided inasmuch as it regards the human being as by nature free, or (and this amounts to the same thing) takes the concept as such in its immediacy, not the Idea, as the truth.Footnote 137

Thesis and Antithesis in this antinomy thus stand for opposite evaluations of slavery: according to the Thesis, slavery is justified, while according to the Antithesis, it is illegitimate. Yet, as with all antinomies, in Hegel’s view,Footnote 138 both positions are one-sided and must be integrated into a more comprehensive conception (more on this later).

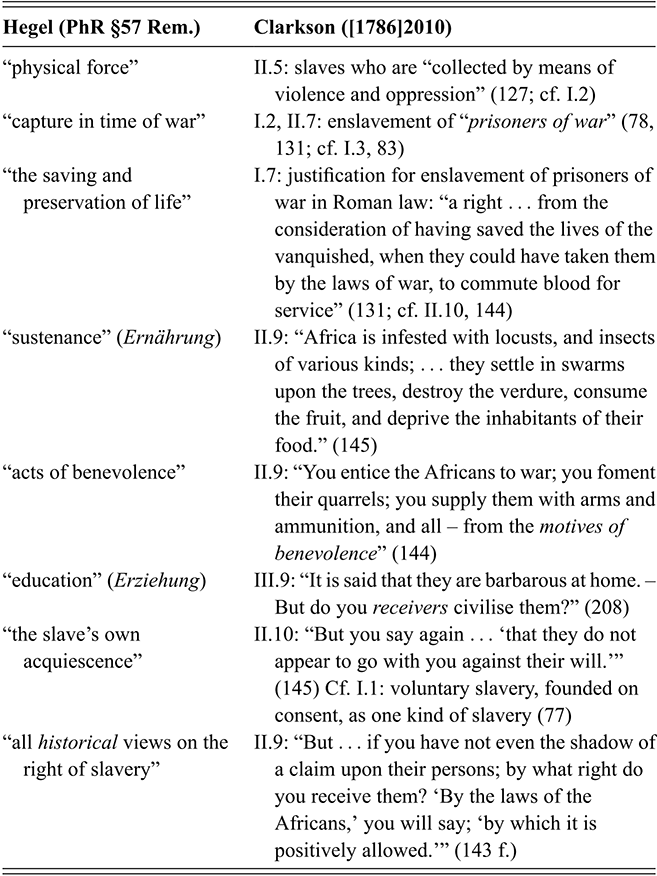

Some commentators have connected §57 Remark to ancient Greece and RomeFootnote 139 and the Thesis to Aristotle’s doctrine of natural slavery.Footnote 140 However, this cannot explain Hegel’s detailed catalogue of justifications or “explanations” for slavery: “physical force, capture in time of war, the saving and preservation of life, sustenance, education, acts of benevolence, the slave’s own acquiescence”, in addition to “all historical views on the right of slavery”.Footnote 141 None of these points matches Aristotle’s views on natural slavery nor other references that have been proposed.Footnote 142 Instead, one needs to see Hegel’s discussion in the context of contemporary debates on slavery in Great Britain to make sense of those details.

While there had been long-standing traditions of resistance against slavery in the British Empire – including the creation of militant maroon societies, slave rebellions, legal action (Somerset v. Stewart, 1772) and anti-slavery writing by authors such as Aphra Behn, Granville Sharp, and Anthony Benezet, only in the 1780s did there emerge a campaign in the metropole that eventually led to the 1807 ban on the slave trade.Footnote 143 One important figure in this campaign was Thomas Clarkson (1760–1846).Footnote 144 In 1785, while a student at Cambridge, Clarkson wrote a prize-winning essay against slavery and the slave trade. Subsequently, he realised that his arguments demanded action. He cofounded the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787 and cooperated with other white abolitionists like Sharp and William Wilberforce, as well as Black abolitionists like Ottobah Cugoano and Olaudah Equiano. Besides, he published an English translation of his Latin student essay under the title An Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Particularly the African (1786). The text became an important document for the abolitionist movement, also internationally. It was widely reprinted, and as late as 1846, the year Clarkson died, several obituaries in German newspapers referred to him as the author of the “famous” Essay.Footnote 145

Hegel very likely was among Clarkson’s readers in Germany. For each of the items on his list of pro-slavery arguments corresponds to an argument that is presented and rebutted by Clarkson, as shown in Table 1.

| Hegel (PhR §57 Rem.) | Clarkson ([Reference Clarkson1786]Reference Clarkson2010) |

|---|---|

| “physical force” | II.5: slaves who are “collected by means of violence and oppression” (127; cf. I.2) |

| “capture in time of war” | I.2, II.7: enslavement of “prisoners of war” (78, 131; cf. I.3, 83) |

| “the saving and preservation of life” | I.7: justification for enslavement of prisoners of war in Roman law: “a right … from the consideration of having saved the lives of the vanquished, when they could have taken them by the laws of war, to commute blood for service” (131; cf. II.10, 144) |

| “sustenance” (Ernährung) | II.9: “Africa is infested with locusts, and insects of various kinds; … they settle in swarms upon the trees, destroy the verdure, consume the fruit, and deprive the inhabitants of their food.” (145) |

| “acts of benevolence” | II.9: “You entice the Africans to war; you foment their quarrels; you supply them with arms and ammunition, and all – from the motives of benevolence” (144) |

| “education” (Erziehung) | III.9: “It is said that they are barbarous at home. – But do you receivers civilise them?” (208) |

| “the slave’s own acquiescence” | II.10: “But you say again … ‘that they do not appear to go with you against their will.’” (145) Cf. I.1: voluntary slavery, founded on consent, as one kind of slavery (77) |

| “all historical views on the right of slavery” | II.9: “But … if you have not even the shadow of a claim upon their persons; by what right do you receive them? ‘By the laws of the Africans,’ you will say; ‘by which it is positively allowed.’” (143 f.) |

In addition, Hegel’s Antithesis, which “regards the human being as by nature free”,Footnote 146 seems modelled on Clarkson’s own position, which follows the natural law tradition and holds that humans are free by birth: “[L]iberty is a natural, and government an adventitious right because all men were originally free”.Footnote 147

Within the abolitionist literature, this combination of debated arguments and claims is, as far as we can see, unique to Clarkson’s Essay. We therefore take this comparison to show that Clarkson’s Essay was Hegel’s direct source for his antinomy of slavery.

Consequently, the discussion of slavery in §57 Rem. must be seen first and foremost in the context of transatlantic slavery. It is also worth noting that Hegel could find in Clarkson’s Essay plenty of information about the atrocities of slavery, in addition to a spirited attack on anti-Black racism; Clarkson points to the Black poets Phillis Wheatley and Ignatius Sancho as “examples of African genius”Footnote 148 and quotes extracts from Wheatley’s poems. When Hegel propagates pro-slavery positions and racist views, he does so not in ignorance but despite his knowledge of critical voices.

3.2 Resolving the ‘Antinomy of Slavery’

To see why Hegel thinks both positions in the ‘antinomy of slavery’ are one-sided, it is helpful to consider that antinomy against the background of his more general views about freedom. Hegel’s discussion of the antinomy is informed by his understanding of the kind of freedom that is, in his view, part of personhood, namely, the “personality of the will”.Footnote 149 Generally speaking, freedom is not simply given for Hegel – a permanent property that a creature is either born with or forever devoid of. Instead, freedom needs to be achieved through a process of development or education. This process begins with humans as bearers of a “natural will” who cannot yet rationally control and order their drives and motives.Footnote 150 It subsequently creates the mental and social preconditions that enable humans to be guided by reason and right. For Hegel, the two sides in the antinomy correspond to two ways of understanding human existence, which both abstract away from essential parts of this process. First, if humans in their initial state of “natural beings” are taken as a paradigm, human existence is understood as “conceptless”, i.e., in isolation from the essence or “concept” of humankind, which is freedom. The Thesis thus erroneously takes a mere initial phase of development as the entire truth:

This earlier and false appearance [Erscheinung] is associated with the spirit which has not yet gone beyond the point of view of its consciousness; the dialectic of the concept and of the as yet only immediate consciousness of freedom gives rise at this stage to the struggle for recognition and the relationship of lordship and servitude (see Phenomenology of Spirit, pp. 115ff. and Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, §§325ff.).Footnote 151

Hegel explicitly refers here to the accounts he offers in the 1807 Phenomenology of Spirit and the 1817 Encyclopedia of the dialectic of lordship and bondage, an argument that is supposed to show that a view of freedom (or ‘independence’) as domination is unstable and that the master–servant hierarchy necessarily gives place to more elaborate conceptions and realisations of freedom.

Second, the opposite error consists in holding fast to the essence (concept) of humans as freedom while abstracting away from its processual nature. Here, freedom is seen only as a “subjective concept”, a mere ideal that is not realised because its necessary preconditions are not in place. Thus, the Antithesis claims that humans have an absolute right to be free, ignoring that such a right has to be institutionalised:

But that the objective spirit, the content of right, should no longer be apprehended merely in its subjective concept, and consequently that the ineligibility of the human being in and for himself for slavery should no longer be apprehended merely as something which ought to be, is an insight which comes only when we recognise that the Idea of freedom is truly present only as the state.Footnote 152

By contrast, Hegel’s processual view of freedom integrates both sides. Since he rejects both the outright assertion and the outright denial of the legitimacy of slavery as one-sided,Footnote 153 he seems to hold that slavery is legitimate in some qualified manner, contextualising slavery within the process leading towards the full realisation of freedom.Footnote 154 But what does this concretely mean?

In the following, we develop an answer by examining how Hegel elaborates his position in other texts.Footnote 155 It will be useful to distinguish here between two different levels:

(a) the qualified justification of forced labour; as we will see, Hegel holds that all human groups at some point of their history go through a stage at which some form of forced labour is justified;

(b) the qualified justification of the enslavement of Africans by Europeans in transatlantic slavery, as a particular historical case of forced labour.

In Section 3.3, we reconstruct three strands of argument in Hegel’s texts that speak to (a) (even though they are often formulated specifically in terms of slavery). In Section 3.4, we examine why Hegel thinks that in the case of Africans, the specific regime of enslavement by Europeans is qualifiedly justified. In the course of our discussion, we will also clarify in what sense forced labour and transatlantic slavery are “qualifiedly justified” for Hegel.

3.3 Justifying Forced Labour

1. The educational argument. In an 1822 lecture on the dialectic of lordship and bondage, Hegel argues as follows:

The ambivalence that Hegel ascribes to slavery here echoes the ‘antinomy of slavery’ introduced in Section 3.1. But Hegel also offers a concrete candidate here for an aspect of slavery that can be thought to justify slavery and, more generally, forced labour: namely, a supposed ‘disciplining’ or educating function.Footnote 157All peoples had to go through the standpoint of servitude, and owe it only to the disciplining rod [Zuchtruthe] that a self-consciousness has awaked in them which is not the self-consciousness of mere individuality. … On the one hand, one can … reject slavery as illegitimate; on the other hand, one can recognise it as grades of discipline [Stufen der Zucht].Footnote 156

The cynical claim that forced labour has a disciplining or educating effect can already be found in the seventeenth centuryFootnote 158 and is part of the arguments used by the plantation lobby in the British debate around 1800.Footnote 159 It will serve as justification for forced labour well into the twentieth century, both in the context of colonialismFootnote 160 and of totalitarian regimes like Nazi Germany.Footnote 161 However, when Hegel uses this point in his lectures, he also directly builds on an element already central to the dialectic of lordship and bondage in the 1807 Phenomenology of Spirit. According to both the 1807 and the later versions of that dialectic, individuals who attempt to receive confirmation of their initial self-understanding as ‘self-sufficient’ beings – beings that everything else is subordinate to – need to go through a struggle for recognition in which they risk their life to show that nothing, not even their biological lives, has absolute value for them. Recognition occurs only once one side surrenders, leading to a hierarchical relation between a master and a servant. However, while the recognition from someone they treat as an object is worthless to the master, the servant benefits from the situation. According to the 1807 version, one reason for this lies in the ‘disciplining’ role of forced labour. Unlike the master, the servant is forced to control their desires: for example, they cannot simply do whatever they want since they have to work for the master, nor can they eat the fruits of their labour whenever they wish to because they need to supply them to the master. Thus, the servant “works off his natural existence”; their work is “desire held in check, it is vanishing staved off, or: work cultivates and educates”.Footnote 162

Both in 1807 and in later versions, the ‘education’ of the servant is a precondition for the subsequent development towards freedom and mutual recognition. What is new in the later texts is that Hegel explicitly applies that point to the level of human groups and their history, arguing that a stage at which societies are organised by master–servant relations is a necessary element in the development of all societiesFootnote 163 (although we will see in Section 5.3 that the 1807 version already echoes debates on this topic). In addition, Hegel now uses the tools of his mature philosophy to unpack the reasons for assigning master–servant relations such a necessary role. Consider, to begin with, how Hegel continues the discussion we cited at the beginning of this subsection:

Hegel claims here that habitual subordination under someone else’s will in forced labour eventually affords subjects a form of self-control they need to subordinate themselves to social norms. Participation in norm-governed social orders is central to ethical life and, hence, to freedom in Hegel’s mature conception. At the same time, as we saw earlier, he holds that humans initially have a merely “natural will” governed by brute desires and drives – hence the need for learning self-control.Footnote 165 In the course of socio-historical development, teaching self-control eventually becomes a part of ordinary parenting practices.Footnote 166 However, at the early stages of such development, parents themselves lack control over their will. Therefore, they are unable to educate others, as a capricious will does not instil respect and obedience.Footnote 167 Instead, Hegel thinks that self-control initially needs to be acquired through forced labour – where the master may themselves be stuck at a level of mere consumption of goods,Footnote 168 but the specific situation of forced labour with its need to obey, and to supply rather than consume goods (on pain of fatal violence) ensures that the servant develops abilities for self-control.That humans be free, this includes that their individuality be no longer natural, but that they have sublated it into the universality of their life; initially, this is the relationship in which the servant stands; he subordinates his self-sufficiency. The absolute relationship of freedom obtains when the other to which one subordinates oneself is universal … rationality. The servant, by contrast, still subordinates himself to an individual will and has now the negative relation to himself of working away, breaking his selfish will. … This negation has to become a habit, and this is what one calls discipline [Zucht].Footnote 164

The reasoning we have reconstructed so far in this subsection amounts to a first argument that, in Hegel’s view, offers a qualified justification for forced labour: freedom qua ethical life requires abilities for norm-following and hence self-control, which, in turn, presuppose disciplining processes, including a regime of forced labour as a stage of socio-historical development. Forced labour during that phase of development will then count as a ‘necessary evil’ – evil as it contradicts the human vocation for freedom but necessary as there cannot be such freedom without it.

2. Argument from personhood. A second, related strand of argument becomes visible when we consider the rights that, in Hegel’s view, protect members of a free society against forced labour. These are individuals’ institutionalised rights over their bodies and labour, rights that he conceptualises as property rights (“because the slave has no property, he is a slave”).Footnote 169 However, to possess such rights, individuals must be granted them by others: they must be recognised as property holders. Such recognition – Hegel calls it “respect”Footnote 170 – involves leaving it up to the individuals in question to decide how they act, both with respect to the external things (Sachen) they own and their own lives and bodies.Footnote 171 This ability is, for Hegel, part of what it is to have a personal will, to enjoy personal freedom.Footnote 172 Moreover, for subjects to enjoy such personal freedom safely – independently of whether their decisions match others’ interestsFootnote 173 – it must be instituted in the form of private property rights, a norm-governed social order that constrains the will of all in accordance with their mutual recognition as property holders. Because to have a personal will just is to be a person (for Hegel), private property institutes personhood.Footnote 174 As Hegel puts it in his peculiar terminology: “Private property is the determinate being of my personality [das Dasein meiner Persönlichkeit]”.Footnote 175

However, this institution requires that human beings have acquired the ability to respect others and themselves as property holders and act accordingly – in particular, to restrain themselves in accordance with the property claims of others insofar as they are in line with institutional norms. In turn, this requires the ability for self-control discussed in connection with the “educational argument”. If that ability has not yet been widely acquired in a group, there are no property rights that could protect members of that group against enslavement or other forms of forced labour, either. Hence, until forced labour has fulfilled its disciplining task in a group, it is qualifiedly justified also insofar as group members have not reached personhood, with the consequence that there is no rational basis for institutionalised property rights that could protect them: “Slaves are not persons, for they want according to their drives, needs, but not as a free subject”.Footnote 176

3. Cowardly contract argument. There is another element in the 1807 dialectic of lordship and bondage that Hegel later uses to supplement further his qualified justification of forced labour: the notion that the master–servant hierarchy emerges because one of the subjects has surrendered. This later becomes the basis for different versions of what has been called the “cowardly-contract” defence of slaveryFootnote 177 – slavery and forced labour, more generally, are justified because the enslaved or servant could have chosen death instead: “[W]hen a human is a slave, it is their will; for they do not need it; they can kill themselves”.Footnote 178 Moreover: “One who cannot risk their life for their freedom is worth being a slave”.Footnote 179

The first quote suggests that slavery is qualifiedly justified as the enslaved consented to their condition by preferring it over death. This is a weak argument even by the lights of a pro-slavery advocate, as it obliterates the difference between forced obedience and free consent. The second quote points to a somewhat different argument, which is further illuminated by a denigrating remark Hegel makes on African societies: “there is the greatest lack of consciousness of personality in this condition; this is why they let themselves enslave so easily”.Footnote 180 Hegel assumes here a particular explanation for why the enslaved did not risk or actually take their own lives, an explanation that is directly connected to the status of personhood that we just discussed.Footnote 181 For Hegel, such personhood has a reflective dimension: it requires an awareness of oneself as a person who respects others and themselves as property holders and is able and willing to act accordingly – i.e., of oneself as possessing personal freedom.Footnote 182 Against this background, Hegel takes the fact that the enslaved are still alive to show that they lack such awareness of freedom (otherwise, they would have risked and lost their lives to defend their liberty).Footnote 183 It follows that they also lack personhood and hence (per ‘argument from personhood’) protection by institutionalised property rights. (Notice that Hegel also endorses the flip side of this argument: the enslaved always have the right to escape.Footnote 184 When they do so, they demonstrate that they have acquired personhood and that their enslavement is no longer justified.)

To summarise the results of this subsection: Hegel thinks it follows from central elements in the dialectics of lordship and bondage and his mature social philosophy that forced labour is justified during stages of socio-cultural development where individuals are not yet enabled to self-control by ordinary processes of socialisation. At such stages, forced labour is justified, for Hegel, (1) as a necessary evil that, in virtue of its disciplining function, is required for the realisation of freedom (educational argument), and (2) insofar as members of such societies lack personhood, and hence also institutionalised property rights that would protect them against forced labour (argument from personhood); moreover, (3) such lack of personhood is proven by the fact that forced labourers have not preferred death instead (cowardly contract argument).

3.4 Justifying Transatlantic Slavery

That Hegel takes the arguments examined in the last subsection to apply to the specific case of transatlantic slavery becomes particularly clear in a passage from his lectures on the Philosophy of History in 1830/1831. In the context of a discussion that contrasts transatlantic slavery with domestic slavery in Africa (an issue we will return to shortly), he declares (in Karl Hegel’s transcript): “Slavery is in and for itself unjust, for the essence of humans is freedom; but they first must become mature for it and while the Europeans acknowledge that slavery is indeed wrong, they would act equally unjustly if they would immediately bestow freedom upon the negro slaves”.Footnote 185 Wichern’s version adds: “the taming of their natural disposition has to precede their real freedom”.Footnote 186 Here, Hegel explicitly ascribes the disciplining function that the educational argument hinges on to transatlantic slavery. As this entails that the enslaved Africans lack the self-control needed for personhood, the argument from personhood applies here, too, and it is clear from the passages we cited in connection with the ‘cowardly contract argument’ that Hegel takes this argument to apply to enslaved Africans, as well.

Hegel’s view that people from sub-Saharan Africa lack the abilities required for self-control is part of his hierarchical metaphysics of race (cf. Section 1.4). Hegel claims that they are characterised by “unbridledness”,Footnote 187 by “sensuous caprice with the energy, power of the sensuous will”,Footnote 188 unable to develop a grasp of universal norms (“the universal does not raise in their heads”)Footnote 189 or to subordinate their actions to a shared “universal purpose”.Footnote 190 Lacking personhood and the awareness of one’s personal freedom that comes with it, “man” in Africa “does not have genuine respect for himself and for others”; Africans fail to appreciate the “absolute value that humans have in themselves”,Footnote 191 which purportedly leads to mutual enslavement.Footnote 192

So, while in Asian and European societies, the necessary stage of forced labour belongs to a “prehistorical” past,Footnote 193 Hegel confabulates innate racial characteristics of Africans that, he claims, prevent them from developing abilities of self-control and corresponding practices of education – apparently, both insofar as said characteristics make it particularly difficult for Africans to learn to control themselves and insofar as they cause slave-holders within domestic African slavery to be capricious masters,Footnote 194 who further impede such learning and even, Hegel believes, cannibalise the enslaved.Footnote 195 For these reasons, Africans are stuck in “the intermediary condition between the state of nature and the transition to a more developed state”,Footnote 196 i.e., in relations of mutual enslavement and arbitrary despotism, and “are not able themselves to overcome their naturalness”.Footnote 197 This also means, for Hegel, that Africans have so far been unable to build more advanced socio-political institutions, in particular statesFootnote 198 – hence Hegel’s notorious claim that sub-Saharan Africa has never entered world history.Footnote 199

For Hegel, people from Africa are therefore not protected by property rights against enslavement (per ‘argument from personhood’ and ‘cowardly contract argument’), and they still need to undergo some form of forced labour further to eventually become able to participate in free societies (per ‘educational argument’). But in addition, Hegel can use his racial assumptions about Africans also to argue that it is specifically enslavement by a supposedly more advanced racial group that is justified here as a ‘necessary evil’ rather than the relevant alternatives, namely (a) domestic African slavery and (b) a less brutal regime – like feudal servitude or the subsistence economy of the Jesuit reductions. As to (a), Hegel imagines enslavement by Europeans rather than Africans to be a “mode of becoming participant in a higher morality and the culture connected with it”:Footnote 200 it ensures that the enslaved do not get cannibalised, it subjects them to a form of forced labour that is more orderly than in African domestic slavery, and it puts the enslaved in contact with European culture. In particular, it forces the enslaved to carry out agricultural labour, which, as we will see in Sections 4.4 and 5.3, has its own educating effect in Hegel’s view.

Regarding (b), we saw already that Hegel refers to transatlantic slavery as a “taming of the natural disposition” of the enslaved.Footnote 201 The choice of the term “taming” – as if the slave-holders were trying to domesticate wild animals rather than mistreating fellow human beings – suggests the following reading: given the racial characteristics (“natural disposition”) of Africans, only their brutal treatment in slavery, not some ‘milder’ form of forced labour, is apt to exert the required disciplining function that will eventually change the relevant racial characteristics (cf. Section 1.4). Notice that this reading is coherent with our findings in Section 2: Hegel sees European colonialism as racial domination; its precise modality should depend on the supposed racial characteristics of the colonised and enslaved.

To wrap things up: for Hegel, transatlantic slavery is justified up until the point when the enslaved have collectively become capable of self-control and participation in a norm-governed society; it is justified during that time both insofar as the enslaved lack protection by property rights, and because given the racial characteristics of Africans, enslavement by a racially superior group, in this case the Europeans, is required as disciplining means for them to become capable of self-control and, ultimately, freedom.

3.5 Hegel on Abolition

Having thus reconstructed the arguments by which Hegel purports to qualifiedly justify forced labour, and in particular the enslavement of Africans, we can now examine what position in the contemporary debate on abolition his views might align with.

Let us first consider the state of the British debate in the 1820s. After the campaign against the British slave trade eventually led to its ban in 1807, the focus of the debate moved initially to other European countries’ slave-trading activities. By contrast, calls for the abolition of slavery itself became loud only in the 1820s, and even then (and until ca. 1830), the dominant view among white abolitionists called for gradual rather than immediate emancipation.Footnote 202 It was thought that slavery had such a corrupting and dehumanising effect that the enslaved were not presently capable of living in freedom. Instead of immediate abolition of slavery, there was a need, in this view, for a transitional phase of mitigated captivity in which the enslaved would slowly get accustomed to freedom. (This contrasts with the immediatist positions championed by Black abolitionists – such as the 1823 Demerara insurgents whose demands Hegel could read about in the British newspapers – and by female white abolitionists, including Elizabeth Heyrick, author of the seminal 1824 pamphlet Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition.Footnote 203)

Importantly, the notion that slavery should be gradually abolished because the enslaved persons were not considered to be ready for freedom was also common, at least at the level of public rhetoric, among plantation lobbyists of that time. They realised that by espousing this position, they could maintain the status quo while pleasing public opinion. As historian Gordon Lewis observes, this “was merely a desperate effort to save time; emancipation was accepted, but always at some safe, distant future date, never at the present moment”.Footnote 204 Hence, gradualism about emancipation was common ground between most British abolitionists and the plantation lobby in the 1810s and 1820s; the difference between the parties lay in the justifications they gave for the alleged need for continued slaveryFootnote 205 and in the practical implications of those justifications. Rather than pointing to the disastrous psychic effects of enslavement as the abolitionists did, planters were more likely to argue for gradualism on racial grounds, claiming that Africans qua race are uncivilised and incapable of freedomFootnote 206 – and implying that slavery would, therefore, have to remain in existence much longer than abolitionists would think.

A further ambiguity of British debates on slavery of that time concerns the attitude towards the enslaved persons’ liberation struggles. While some abolitionists welcomed and defended the slave uprisings,Footnote 207 the perception of the Haitian Revolution as a brutal massacre against the white population of Saint Domingue was widespread among the British public.Footnote 208 This led to the view, common also among white abolitionists, that “emancipation symbolised all the horrors of race war dramatised in St. Domingue”.Footnote 209 Indeed, many white abolitionists distanced themselves from the violence of slave rebellions, emphasising that they demanded gradual reform of slavery, not its sudden overthrow.Footnote 210

Given this background in the 1820s, how did Hegel think about the abolition of slavery in that period? The available lecture transcripts relate two occasions on which Hegel takes an explicit stand. First, an anonymous transcript of the lectures on the Philosophy of Right in 1821/1822 reports the following statement “concerning the abolition of slavery”: “As horrible consequences were feared from sudden abolition, one looked for slower means. The principle is right, but it belongs to a concrete state of affairs, which can demand more than that this relation gets suddenly severed. Slaves who have never been free, are in need of an education”.Footnote 211

The second statement is found in transcripts of the lectures on the Philosophy of History in 1830/1831; we have already quoted parts of it: