1 A Theory of Gendered Role Congruity and Local Political Leaders

Someone said to me, ‘women do all the work. They do non-profit work and volunteer and take care of the children and the elderly. And then they turn around and have to be supplicants to the men in power. ‘Please, sir, can we have some money for our schools and the disabled?’ I hate that. We need to stop being the supplicants and actually be the ones in power. Maybe men should be the ones doing bake sales to get money for their guns and wars. Why should a school even need a bake sale?

The ideal political candidate in the United States is well connected, organised, ethical, hardworking, and prepared to handle long hours, intense interaction with people, and difficult situations. Nurses, teachers, and social workers all easily meet these criteria. Why, then, are our ballots filled with lawyers, bankers, and business managers? We propose a gendered theory of occupation and political representation and test it in the local political environment of the United States. We show that the alignment of a candidate’s gender, the gender typically associated with the candidate’s occupation, and the office they are seeking all interact to influence candidate emergence (who runs) and voter choice (who wins). As a result, ballots for mayor, city council, and sheriff are filled with men with experience in business, law, and science. But in other local offices, such as school board, community services director, and city clerks, we see a robust group of teachers and non-profit leaders running for office. The gender segregation of these occupations thus passes on to produce further gender segregation in who holds local offices.

Running for political office is an extraordinarily rare activity. Less than 2 per cent of Americans will ever become a political candidate. Those who do choose to run are exceptional in many ways: they are wealthy, have access to a wide set of professional and financial resources, and are highly motivated (Bernhard, Eggers, & Klašnja, Reference Bernhard, Eggers and Klašnja2024; Bernhard, Shames, and Teele, Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021; Conroy & Green, Reference Conroy and Green2020; Sweet-Cushman, Reference Sweet-Cushman2020b). That white men make up most of the people who run for and hold office is one of the most reliable and most damning features of modern American democracy.

In this Element, we provide four new lenses through which we can examine the root causes of the overrepresentation of white men in office. First, we draw on the Census to document the occupational backgrounds of more than 37 million men and women in the general population in California, and combine it with data on nearly 100,000 candidates for and winners of California political offices. The wealth of data provides a much richer and wider view of how ordinary residents run for office. By comparing candidates and winners to the general population, we can see the gendered and occupational pathways to local offices in new and exciting ways. Second, we complement our quantitative data with qualitative studies of prospective candidates’ decision-making processes about whether to enter politics, giving us a deeper sense of what those numbers actually mean. Third, we examine a much wider set of offices than researchers traditionally use when they examine gender, occupations, class, local politics, or political engagement more generally. Finally, we combine this broad set of observational data with innovative surveys and experimental work to show that the public understands occupations, offices, and the combination of the two as highly gendered. The combination of these approaches allow us to demonstrate that opting into politics is rooted masculine occupations, that the pool of candidates fails to represent the gender and occupation composition of the population, and that the sources of power in local politics largely remain in the hands of men from a narrow set of masculine occupational backgrounds. The offices that women do run for are seen as more feminine and less prestigious.

Women hold less than a quarter of seats in the US Congress, less than a third of state legislative seats, and only one in four mayors of large cities are women (CAWP, 2020; de Benedictis-Kessner, Einstein, & Palmer, Reference de Benedictis-Kessner, Einstein and Palmer2023); similar levels of underrepresentation are seen among women in municipal government in other countries (Funk, Reference Funk2015; Tolley, Reference Tolley2011). Women of colour are particularly underrepresented in US political office, making up less than 10 per cent of both the US Congress and state legislatures. And, of course, the United States has never elected a woman president and only one woman has served as a vice president; this has normative consequences (is a democracy democratic if half of the population is routinely excluded from power?Footnote 1) and means that political institutions in the United States are less efficient, solve fewer problems, and are seen as less legitimate and trustworthy. The majority of what we know about women in politics is among the very elite: women who run for national and high-level state offices. But more than 95 per cent of the elected offices in the United States are found at the local level, and we know much less about this group, particularly offices like school board, county sheriff, and city treasurer.Footnote 2

Women’s lack of access to political office implicates underlying social and cultural ideas about gender. Every society is organised around gendered social roles, which are patterns in behaviours and attitudes exhibited by men and women (Eagly & Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002). Gender role theory argues that society trains men and women to fulfil specific, socially constructed roles (Blackstone, Reference Blackstone2003; Eagly & Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Gould, Reference Gould1977; Schneider & Bos, Reference Schneider and Bos2019). A consequence of these gender roles is that women are socialised and expected to be ‘good at’ tasks associated with the private sphere: for instance, taking care of children, helping others, and collaborating to solve domestic problems. Likewise, men are socialised to be ‘good at’ tasks associated with the public sphere: working outside the home, protecting women and children from outside threats, and providing leadership (Schneider & Bos, Reference Schneider and Bos2019).

Socialisation in both childhood and adulthood teaches men and women about appropriate behaviour and goals for their gender (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2021; Diekman & Murnen, Reference Diekman and Murnen2004). These patterns are reinforced through internal and external social rewards and punishments (G. Bauer & Dawuni, Reference Bauer and Dawuni2015; Cassese, Reference Cassese2019). Researchers talk about those individuals whose appearances and behaviours match their assigned gender roles as being gender role-congruent, and those who don’t as gender role-incongruent (Eagly & Koenig, Reference Eagly, Koenig, Canary and Dindia2006).

One persistent consequence of social gender roles manifests as occupational segregation by gender. A combination of historical discrimination (Zellner, Reference Zellner1972), the gendered nature of the household and the economy (Gingrich & Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; Iversen & Rosenbluth, Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2008), and gender roles (Diekman et al., Reference Diekman, Clark, Johnston, Brown and Steinberg2011) push and pull women into feminine-typed careers like teaching, nursing, and social work, while men are much more likely to become engineers, construction workers, and business owners. Those who conform more highly to their gender roles—for instance, men who are firefighters (working, physically protecting others) and women who are preschool teachers (caring for children, helping others)—fulfil societal expectations and thus tend to be valorised. This means that gender roles push and pull women towards some careers and interests and men towards others (Diekman et al., Reference Diekman, Brown, Johnston and Clark2010). Gendered patterns of interest then interact with a gendered economic system (Rosenbluth, Light, & Schrag, Reference Rosenbluth, Light and Schrag2004) and historical patterns (He et al., Reference He, Kang, Tse and Toh2019) to structure economic and political patterns in society. One consequence is that women engage in many types of labour in the home for free: ‘a third or more of society’s work’ is performed without compensation by women for their families and communities (Iversen & Rosenbluth, Reference Iversen, Rosenbluth and Wren2013, p. 306).

Gender roles are also racialised. Race, ethnicity, and gender are dominant, intertwined structures in American society (Bejarano & Smooth, Reference Bejarano and Smooth2022; Brown & Gershon, Reference Brown and Gershon2016; Carmines & Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1990; Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1989; Jardina & Piston, Reference Jardina and Piston2019; Omi & Winant, Reference Omi and Winant2014). This means that race and gender intersect to place particular burdens on women of colour (Brown & Gershon, Reference Brown and Gershon2016; Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1991). Women of colour have long worked outside the home, even as many white women stayed home during the mid-1900s (Goldin, Reference Goldin2021). People understand gender in the context of their own racial and ethnic group, which means that penalties and rewards for gender role violations and compliance are primarily meted out to those within their group (Xiao, Reference Xiao2022). While we do not focus on racial or ethnic segregation in occupations here because occupational segregation occurs primarily by gender, it is critical to remember that what is seen as gender role-incongruent (and therefore punished) will vary by race and by gender.

Gender roles shape not just sorting into occupations, but how we think about leadership (Eagly, Reference Eagly2007; Kweon, Reference Kweon2024). Close your eyes and imagine a CEO or leader in a business field. Who do you see in your mind? Does that person have a specific gender? Race? Age? Who we imagine at the ‘top’ of a field, company, or organisation, be it education, business, or politics, is gendered. Women are not seen as easily occupying masculine or leadership roles (Schneider & Bos, Reference Schneider and Bos2019; Schneider, Bos, & DiFilippo, Reference Schneider, Bos and DiFilippo2022; Sweet-Cushman, Reference Sweet-Cushman and Bauer2020a), which include politics (Holman, Merolla, & Zechmeister, Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2022; Oliver & Conroy, Reference Oliver and Conroy2018, Reference Oliver and Conroy2020). And, the occupations that ‘fit’ with our views of political leadership are commonly held by men in society, including business leaders and lawyers.

The intertwined nature of social gender roles and views of leadership have consequences for politics, policy preferences, and interest in running for office (Conroy, Reference Conroy2016; Schneider & Bos, Reference Schneider and Bos2019; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016). Internally, women’s socialisation into communal gender roles leads them to seek out positions that involve working collaboratively with others, interpersonal communication, and helping improve society (Diekman et al., Reference Diekman, Brown, Johnston and Clark2010; Eagly & Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002). While these all are activities that could be fulfilled by political careers, men and women both perceive political careers to instead fulfil agentic gender roles by seeking power, individual autonomy, and strong leadership (Conroy & Green, 2022; Ohmura & Bailer, Reference Ohmura and Bailer2023; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016).Footnote 3 Women are thus less likely to see political careers as consistent with their broader socialised career goals (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016). However, this field of scholarship has not yet considered whether a candidate’s occupation might signal more or less interest in communal activities, or how many local political offices like school board might be seen as more communal (though extensive work has shown that higher-level and executive offices, like the presidency, are seen as more masculine and agentic).

It is not just women’s lack of interest that limits their access to politics: the political system itself is also uninterested in women’s leadership. External factors, including voter biases, political party behaviour, fundraising, and the campaign environment, also suppress women’s political ambition (or inflate men’s ambition). For example, Crowder-Meyer (Reference Crowder-Meyer2013) finds that women are less likely to be a part of local political party networks that are used to recruit candidates for office; this is particularly true when local leaders are men. And, because women generally need more encouragement to run for office than do men (Badas & Stauffer, 2023; Karpowitz, Monson, & Preece, Reference Karpowitz, Monson and Preece2017; Preece, Reference Preece2016; Preece, Stoddard, & Fisher, Reference Preece, Stoddard and Fisher2016), the exclusion of women from these recruitment networks is doubly damning.Footnote 4

One consequence for politics is that voters then hold beliefs about individual capacity for leadership based exclusively on that individual’s gender. These stereotypes can include that women will be better at producing policy in areas like education and welfare, or that men are stronger leaders (Bernhard, Reference Bernhard2022; Holman et al., Reference Holman, Merolla, Zechmeister and Wang2018). Because political leadership is associated with the traits and skills that men are socialised to be better at, voters can hold biases against women seeking positions, particularly if those positions are seen as needing strong leadership (N. M. Bauer, Reference Bauer2020a). In previous work, we have shown that these apply across local offices, with voters preferring men for mayoral positions and women for school boards (Anzia & Bernhard, Reference Anzia and Bernhard2022).

Gender stereotypes held by voters serve as a powerful external obstacle to women’s political parity. Here, voters use their knowledge about gender in society to infer information about candidates on the ballot, such as that women running for office will be more compassionate and men with be more assertive and stronger leaders (Barnes & Beaulieu, Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2014; N. M. Bauer, Reference Bauer2015; Bernhard, Reference Bernhard2022; Holman, Reference Holman2023).Footnote 5 Because stereotypes of men are better aligned with the activities associated with political office, voters thus often believe that men will be better at performing the tasks of that office. Such stereotypes are powerful because they are self-reinforcing and built on behaviours that originate from socialised patterns that begin at an early age (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2021). While scholars have pointed to the fact that voters are more ‘tolerant’ of the women running for local positions (N. M. Bauer, Reference Bauer2018) and for specific roles like school board (Anzia & Bernhard, Reference Anzia and Bernhard2022) and city clerk (Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian, & Trounstine, Reference Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian and Trounstine2015), we know much less about how potential candidates and voters weigh gender expectations for the broad set of offices available in local politics.

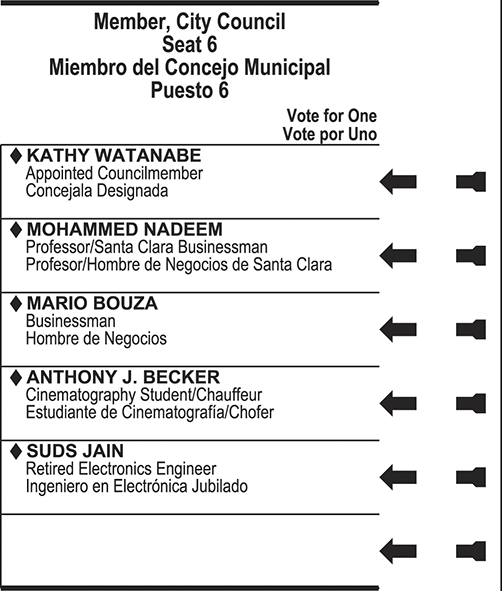

One way that an individual candidate might demonstrate that she is capable of leadership is by emphasising and listing the previous jobs she has held, such as CEO or business owner, as these provide information to voters about the skills and traits of the candidate. Political consultants are especially aware that this is a problem for women. During a California women’s candidate training on ‘Assessing the Political Landscape’, experienced consultants emphasised the importance of the ballot designation, or listing of occupation on the ballot: ‘the public is more skeptical of women’s credentials, so it’s good to describe your credentials in as interesting and detailed a way as possible’ (A., 2/21/16).Footnote 6 For local offices, consultants recommended including descriptors such as education (for school board), finance (for comptrollers), and legal experience (for district attorneys). For the ballot designation to be valid, the occupation or activity must have taken place in the last year, so consultants recommended that candidates volunteer or take on part-time work in relevant areas (e.g., running for president of the school’s parent-teacher organisation) to ensure the strongest possible (valid) ballot designation.

Both existing scholarship and our own interviews of political consultants thus suggest that gender matters in evaluations of leadership; that men and women are seen as capable of different forms of leadership, and that occupations can provide candidates with an opportunity to overcome these views. We know much less, however, about how gendered occupational segregation shapes who runs for and who wins local office. In this Element, we argue that gender and occupation deeply shape both who emerges as a candidate for office and who is ultimately elected.

A New Theory of Occupational Gender Segregation and Local Politics

Weaving together this literature, we argue that there is a relationship between occupational gender segregation and local politics:

∙ As a consequence of gendered social roles and gendered occupational socialisation, women systematically emerge as candidates from feminine occupations and for offices seen as more feminine.

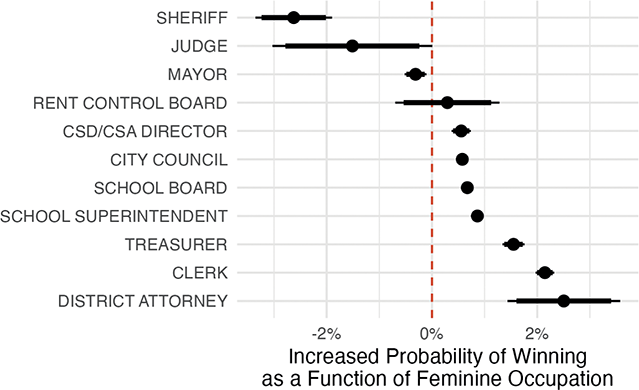

∙ Voters reward candidates whose femininity or masculinity of their occupation matches what they believe to be the work of the specific office.

∙ Women and candidates with feminine occupations are advantaged only for offices considered less powerful and less important.

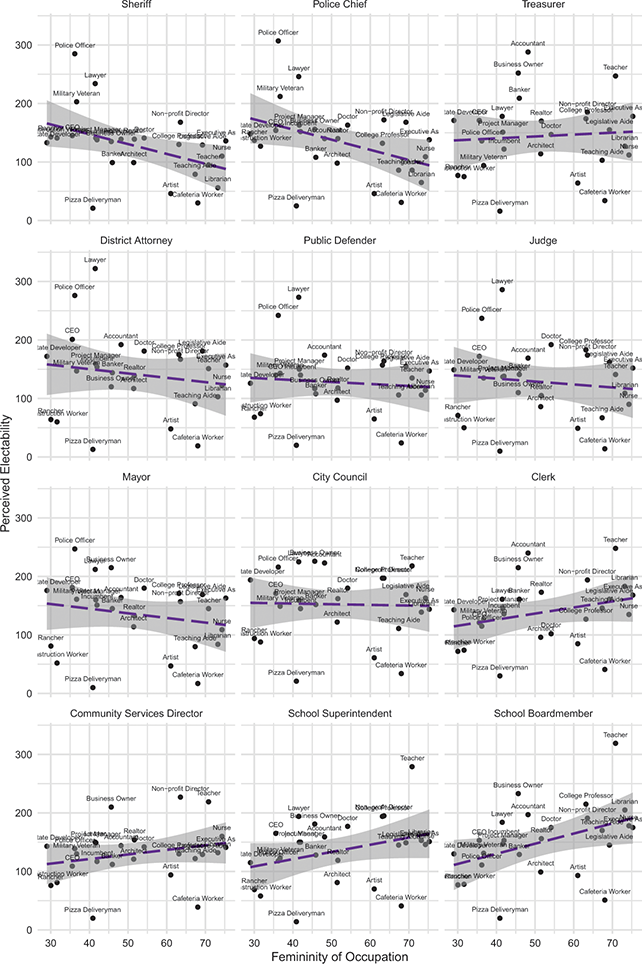

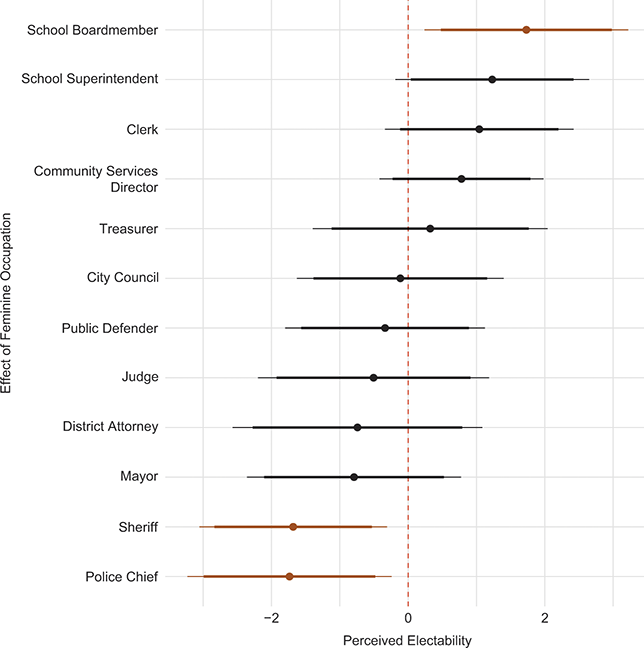

Importantly, not all offices are equally associated with specific prototypes and not all occupations are equally advantaged or disadvantaged across specific offices. In Sections 3 and 4, we provide additional evidence for our theory of gendered occupation and political representation by showing that women emerge as candidates primarily from feminine occupations. In Section 6, we use a new survey experiment to show that voters see candidates from occupations dominated by men as better qualified to hold many local offices, including important offices like mayor. In comparison, feminine occupations like educator and social worker are seen as holding and succeeding only as city clerks and on the school board. In this way, masculine occupations open far more doors for political success than do feminine occupations. Our work shows persistent patterns across time, where gender divisions in labour determine perceptions of occupational femininity; occupational femininity shapes the emergence of candidates for local office; and voters use the femininity of occupations as information about the acceptability of candidates for specific local offices.

We test our theory by examining how gender, race, and occupation shape who runs for office and who wins at the local level, using data from all candidates on the local ballot in California from 1995 to 2021 (Anzia & Bernhard, Reference Anzia and Bernhard2022; Bernhard & de Benedictis-Kessner, Reference Bernhard and de Benedictis-Kessner2021). In California, each candidate provides their occupation, which is then listed in voter materials and on the ballot, often referred to as a ‘ballot designation’. In total, we coded the gender and occupation of more than 99,000 candidates for a wide set of local political offices, from the mayor to city council to sheriff to school board. California provides the ideal environment for examining who runs for local office and who wins, as local elections feature a diverse set of candidates running for local positions that vary in prestige, gender typicality, and electoral environments. We discuss this dataset and our approach of categorising this data in much more detail in Section 2. These occupations vary in their femininity and masculinity; for example, some candidates list occupations like ‘preschool teacher and mother’ on the ballot, while others might list ‘businessman and security guard’.

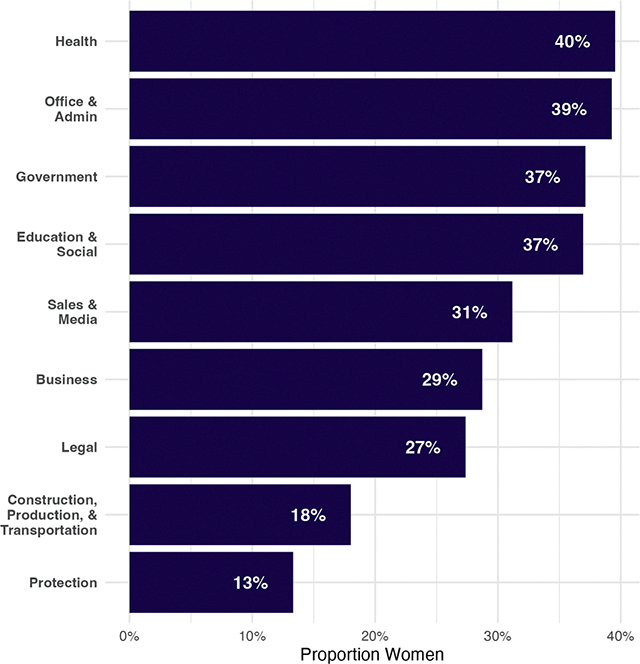

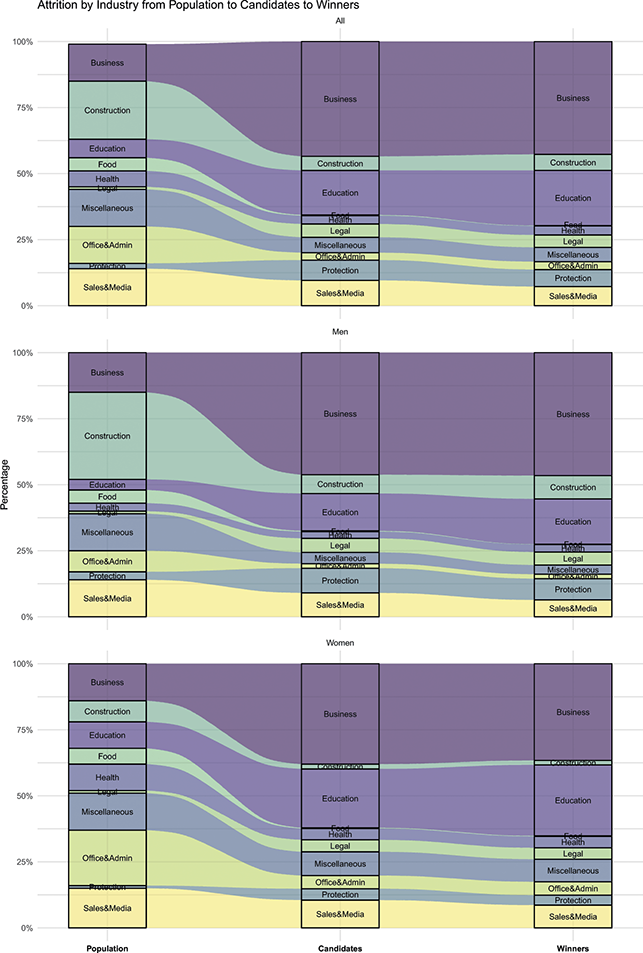

In Figure 1, we provide a first look at our data on political candidates, broken down by gender and occupation. What we can see already is that gender segregation by professional sector is as noticeable within the candidate pool as it is within the greater population. In the following sections, we explore in greater detail why that might be.

Figure 1 Gender segregation by occupation in the candidate pool mirrors the general population. The percentage of political candidates that are women within each professional sector is shown in white font in each bar.

Although local politics offer an ideal opportunity to understand the origins of representation, empirical work examining this topic has been constrained by a host of difficulties: immense variation in electoral institutions and environments across cities, shifting policy challenges within cities over time, and the costs and challenges of collecting data sans standardised record-keeping. Recent work has begun to overcome these challenges (Barari & Simko, Reference Barari and Simko2023; Crowder-Meyer et al., Reference Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian and Trounstine2015; de Benedictis-Kessner & Warshaw, Reference de Benedictis-Kessner and Warshaw2020a), but many major questions remain, including very basic questions about descriptive representation, ambition, and voting behaviour, especially around women in politics. Our work—which combines survey, experimental, and observational data—overcomes some of these limitations and offers a fresh view of one of the most persistent and widespread sources of women’s underrepresentation.

Where does the underrepresentation of women begin? One important and yet understudied source is the gender imbalance in who runs for and holds local office. For many candidates, their first run for office will be for a school board or a city council position, even if their career culminates in a national office (Carroll & Sanbonmatsu, Reference Carroll, Sanbonmatsu and Rose2013; Holman, Reference Holman2017; Sanbonmatsu, Reference Sanbonmatsu2006). Women in Congress, from Kay Granger to Dianne Feinstein to Mia Love, started their political careers as city council members or mayors in their hometowns. Other members of Congress have left federal office to seek local office: Los Angeles’s first woman mayor, Karen Bass, was first a member of Congress, and Sheila Jackson Lee, a long-time member of the House of Representatives, launched an unsuccessful bid to be the mayor of Houston, Texas. Indeed, local offices are often an end in themselves for many individuals, particularly in smaller towns and cities in the United States (Budd, Myers, & Longoria, Reference Budd, Myers and Longoria2016; Einstein et al., Reference Einstein, Glick, Palmer and Pressel2020).

Beyond serving as a pathway to other offices, local politics also is where many of the most pressing issues of our day—like management of restaurant closures and mask mandates during COVID, teaching about topics like LGTBQ + rights and slavery, protections for victims of interpersonal violence, and access to reproductive healthcare—get decided. If women and especially women of colour are excluded from those conversations as elected officials, they remain in the role of ‘supplicants’ (to the men in power) described by City Councilmember S. above.

Despite the importance of local politics, this topic has historically been understudied by the gender and politics community. While we know that having more women in local politics then leads to more women in state politics and eventually to more women in national politics (Carroll & Sanbonmatsu, Reference Carroll, Sanbonmatsu and Rose2013), we know much less about what gets women into (or keeps them out of) local politics in the first place. This dearth of knowledge means that we also know very little about the backgrounds and experiences of these women. What one of the co-authors of this Element wrote in 2017 remains true today: ‘Indeed, scholars of political science, public administration, and urban studies know very little about even basic information about levels of women’s representation, the institutional and demographic factors associated with these levels of representation, or the effects of women’s lack of parity on local policy’ (Holman, Reference Holman2017, p. 285). In short, even at the cutting edge of political science work on local politics, we are just starting to know even basic facts like how many women run for a given local office each year, let alone the complex relationships between characteristics like gender, occupation, and political ambition and attainment.

Outline of the Element

We start our discussion in Section 2 with a discussion of the data sources and methodological approaches that we use in the text. In doing so, we outline the challenges associated with studying local politics, including how and where to get data and why our approach is innovative.

In Section 3, we focus on how gender, occupation, class, and resources shape who runs for local office and why. In the section, we first present extensive descriptive information about the share of women as candidates for a wide set of local offices in California and then compare the share of the population, men, and women from different occupations among Californians, candidates for local office, and winners. In doing so, we show a high level of self-selection from the share of an occupation in the general population to candidates and winners, in highly gendered ways. Only a handful of feminine occupations feed into political office, while people (mostly men) run with a wide set of masculine occupations. As a result, feminine occupations are underrepresented among candidates and elected leaders.

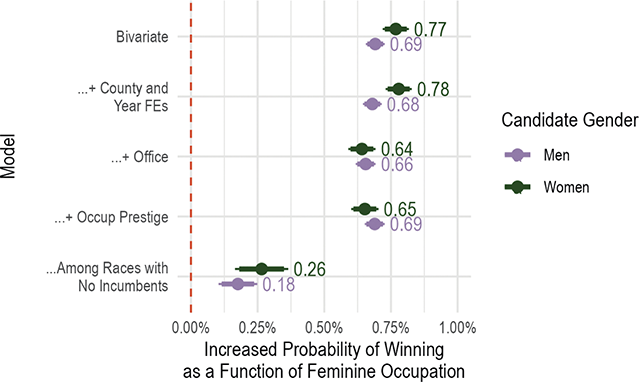

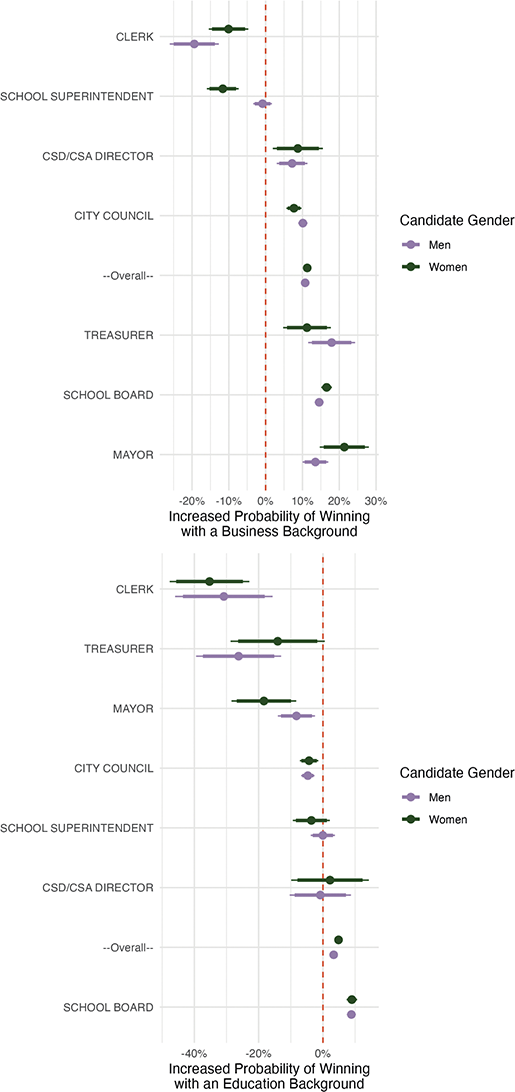

How are masculinity and femininity associated with particular occupations and shape candidates for and winners of local office? In Section 4, we draw on a unique survey to first show that the public assigns femininity to occupations by the share of women in those occupations. We then apply those femininity evaluations to occupations in the candidate dataset and show that candidates who list more feminine occupations on the ballot win several types of local elections, even after controlling for time and location-specific factors.

Section 5 takes a deep dive into two occupational categories: business and education. These two groups are overrepresented among local candidates and have specific skills, networks, and stereotypes associated with them that advantage or disadvantage their efforts to seek office. In the section, we look carefully at how business leaders and teachers describe themselves on the ballot and how these descriptions convey information about the masculinity and femininity of those on the ballot, contributing to the gender gap in candidates and leaders. We show that men and women from business and education backgrounds are similarly successful in seeking office, but that the two backgrounds provide advantages for specific offices. For example, business leaders win most local offices at higher rates than those with other occupations, while teachers are advantaged for school board – but are disadvantaged when seeking offices like mayor or city clerk. Because business leaders are mostly men and teachers are mostly women, men tend to be advantaged when seeking office.

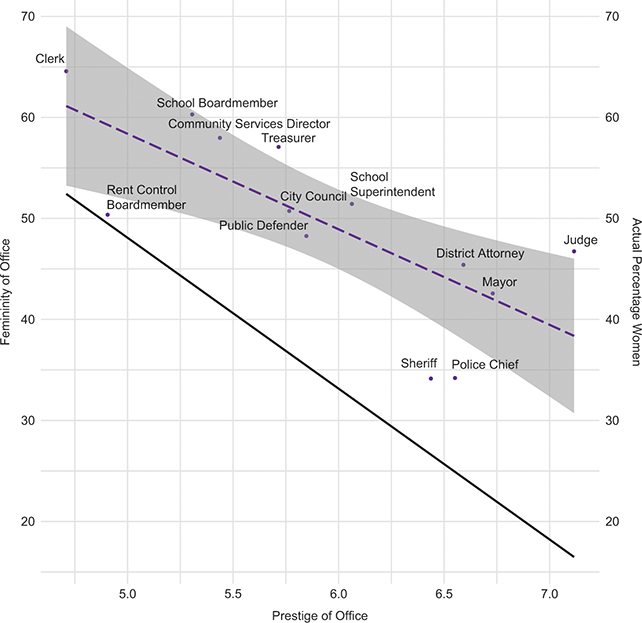

In the last substantive section, Section 6, we examine how voters want leaders who will perform different gender roles for different offices. Using a combination of California election data and a novel survey experiment that asks individuals about their perceptions of different offices and occupations, we show that people’s views of a candidate’s electability to specific offices are rooted in their occupation (i.e., accountants are seen as particularly electable for treasurer positions and teachers for school board) and that the assessments of these occupations and offices are highly gendered such that school boards and clerks are seen as feminine while sheriffs are masculine. We also show that masculinity is highly correlated with prestige, such that the offices that women seek—those seen as feminine—are not considered prestigious.

In Section 7, we conclude by considering what our work says about candidates for office in the United States and around the world. Drawing on comparative work, we consider the ways that our work might translate to other countries—or not—and how factors like sector employment, gender roles, and development play in shaping occupational segregation and women’s access to political power. Our work also allows us to consider questions about how voters evaluate other components of a candidate’s portfolio or identity, including sexual orientation, disability, age, or immigrant status. What we do and do not know about candidates for local office in the United States can tell us much about representation, equity, and democracy.

2 Measuring Gender and Occupation among Local Leaders

How many women are mayors in the United States? Would you be surprised to learn that no one knows? And no one has the capacity currently to know without calling every city and township and county and school board—all 90,000 local governments in the United States? Both coauthors of this Element have spent substantial time grappling with the lack of data about local government in our professional careers.Footnote 7 In this section, we provide information about the data and methods we use in this Element.

One of the downsides of studying inequalities in local politics is that we just do not know a lot about local politics, particularly about how gender operates in these contexts. In many cities and counties, data on elections is not made available to the public, and what is made available often lacks the sort of information that enables easy analysis. For instance, most election data in the United States doesn’t contain information on candidate race, ethnicity, or gender. That means that for very basic questions like ‘How many women ran for office last year in City X?,’ we often can’t answer the question without substantial additional work (de Benedictis-Kessner, Lee et al., Reference de Benedictis-Kessner, Lee, Velez and Warshaw2023). Multiply this work by the nearly 90,000 local governments in the United States (Marschall et al., Reference Marschall, Shah and Ruhil2011), and one can see that this is a task that requires enormous resources and time.Footnote 8

The challenges associated with collecting, cleaning, and collating local elections or candidate information make recent data innovations by scholars working in this area all the more impressive. One strand of innovations falls under the heading of ‘big data’. For many years, scholars working on evaluating the effect of electing women, Black, or Democrat mayors to various offices used a dataset first created by Ferreira and Gyourko (2014), extended by Hopkins and Williamson (Reference Hopkins and Williamson2012), extended again by Hopkins and Pettingill (Reference Hopkins and Pettingill2018), further developed by de Benedictis-Kessner and Warshaw (Reference de Benedictis-Kessner and Warshaw2016, Reference de Benedictis-Kessner and Warshaw2020b), and then used by others (Farris & Holman, Reference Farris and Holman2024; McBrayer & Williams, Reference McBrayer and Williams2022) to test new questions. Eventually, de Benedictis-Kessner, Lee, Velez, and Warshaw (Reference de Benedictis-Kessner, Einstein and Palmer2023) have filled in the missing pieces to produce a dataset that covers nearly 60,000 local elections over more than three decades in most medium and large American cities. The authors use machine learning algorithms to classify the probable partisanship, gender, and race/ethnicity for candidates for city council, mayor, school board, county commission, and sheriff. Similarly, Kirkland (Reference Kirkland2021) has built a dataset of mayoral elections over more than fifty years in medium and large cities, including not just race and gender but also occupational background and prior political experience.Footnote 9 Shah, Juenke, and Fraga (Reference Shah, Juenke and Fraga2022) demonstrate that a collaborative project where many researchers participate is an effective ways of generating a large dataset, while Sumner, Farris, and Holman (Reference Sumner, Farris and Holman2020) point to using crowdsourcing to collect large datasets on local politics. These innovations allow scholars today to ask questions about local representation that had previously been confined either to small samples of cities, case studies, or the examination of only the largest cities. Other works, like Farris and Holman (Reference Farris and Holman2023b) and Crowder-Meyer (Reference Crowder-Meyer2020), weave together survey and interview data to obtain information on the characteristics and attitudes of difficult-to-study groups like sheriffs and budding political candidates. Even with these advances, however, scholars are still limited in their ability to examine smaller cities or more esoteric forms of local government like city clerk (Crowder-Meyer et al., Reference Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian and Trounstine2015) or sheriff (Farris & Holman, Reference Farris and Holman2023b; Thompson, Reference Thompson2022).

California stands out as a special case—one widely used by scholars of local US politics—because it has made available a detailed record of local elections from 1995 to 2021Footnote 10 through the California Elections Data Archive (CEDA). California is also special because its ballots contain ballot designations, which contain information on candidates’ occupations, which can include jobs held and activities like volunteering and parenting. A wide set of scholarly work uses this data in one form or another (i.e., Anzia & Bernhard, Reference Anzia and Bernhard2022; Atkeson & Hamel, Reference Atkeson and Hamel2020; Einstein, Palmer, & Glick, Reference Einstein, Palmer and Glick2019; Hajnal & Trounstine, Reference Hajnal and Trounstine2014; Hankinson & Magazinnik, Reference Hankinson and Magazinnik2023). This data is not error-free; for example, our previous work has audited and corrected numerous errors in the heavily used CEDA data (Bernhard & de Benedictis-Kessner, Reference Bernhard and de Benedictis-Kessner2021).Footnote 11 Other states like Louisiana provide detailed information about the gender, race, and party of all candidates for office (Keele et al., Reference Keele, Shah, White and Kay2017), but do not provide occupation information or require that candidates supply such information directly to voters.

CEDA and Census

Our electoral data come from the California Elections Data Archive (CEDA) and cover elections at various levels of government in California from 1995 to 2021 (Bernhard & de Benedictis-Kessner, Reference Bernhard and de Benedictis-Kessner2021). The CEDA dataset includes information on candidates participating in more than 29,000 elections at the county, city, college/school district, and other local levels. These elections range from those for directors of community services districts, who provide services like water treatment and sanitation in medium-size cities, to mayors and city council members overseeing multibillion-dollar budgets in large cities, to school board races in rural areas with only a few thousand residents.

Unfortunately, this comprehensive dataset is not quite as comprehensive as we need to answer social science questions. For instance, it does not contain any data on the gender, race, or ethnicity of the candidates. To address this problem, we use algorithmic coding to determine the gender of nearly every candidate (categorised as ‘woman’ or ‘man’) with the ‘genderizer’ package in R. Similarly, we use the ‘wru’ package in R to code race and ethnicity. The ‘wru’ package in R relies on US Census data to generate continuous probabilities indicating the likelihood that an individual with a specific name is white, Black, Hispanic, AAPI, Native American, multiracial, or other. This function is configured to consider the location of each candidate in California, taking into account the specific county where the individual is running for office (e.g., the probability that the last name ‘Jefferson’ belongs to a Black individual is higher in Los Angeles than in Tuolumne County). Due to the prevalence of whites in both the US Census and California, this measure may underestimate the likelihood that an individual is non-white, particularly for African Americans.

We also use the CEDA data to analyse the individual occupations of nearly 99,000 candidates on the ballot for local election in California. In local elections in California, all candidates are asked to provide a ‘ballot designation’: a brief (50 characters or less) description of their occupation, which is listed on the ballot next to their name. As an initial occupational coding, we manually coded each candidate’s ballot designation into 540 categories that match the US Census’s Occupational Categories. For example, we would classify someone who lists their job as ‘Barber’ as the Census Occupational Category of 4500: Barbers.

We then group these 540 categories into ten larger sectors and industries, such as business, education, health, and construction. Here, the ‘Barber’ category is grouped in the ‘Personal Care’ category, which includes such other occupations as ‘Embalmers’, ‘Baggage Porters’, and ‘Fitness Instructors’. These are choices that are informed by the Census Bureau’s designation of occupations, industries, and status. This allows us to compare the percentage of the general population in a given industry (using the US Census data for California) to the percentage of political candidates in said industry (using the CEDA data) to the percentage of election winners in said industry. At some points in our analysis, we also create a series of occupational ‘dummy’ categories that allow for an inclusive coding of anyone who lists any job in that occupation.

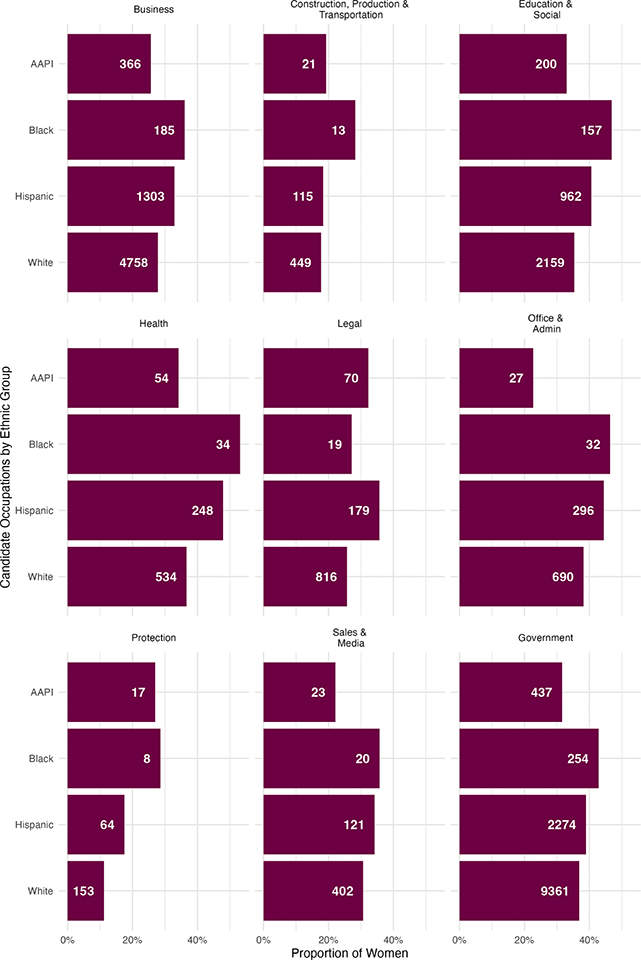

We provide an initial view of what this data looks like in Figure 2, which presents the share of candidates who are women for each of the major race and ethnic groups in our data: Asian Americans/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, and white. The figure also provides a view of the number of women candidates in our dataset. As the figure shows, the share of women in each occupation does vary some across racial and ethnic groups, but at no point do women from any racial or ethnic group cross more than half of any occupational category among our candidates. Because gender segregation by occupation is much starker than racial segregation by occupation, going forward, we do not break our results down by race and ethnicity, but as we know so little about the descriptive representation of women and minorities at the local level, we provide a breakdown by gender and race here. Moving forward in our analysis, we large focus on gender and occupation, leaving questions of race and ethnicity to future work.

Figure 2 Women across racial groups are segregated like the general population. As with the general population, occupational gender segregation is much more dramatic than ethnic segregation by occupation. Number of women candidates per sector and racial/ethnic group is shown in white font in each bar.

By combining the Census with the CEDA dataset, we can examine three full populations: the entire population in the state of California, all of the candidates for local office, and all of the candidates who win local office. At the end of this section, we begin our analyses by comparing the general population to candidates and winners to see who opts into and out of politics by gender and occupation.

Emerge

To understand how potential candidates might make these decisions, we also incorporate data from two years of candidate trainings in California run by a national organisation, Emerge America, which trains progressive women to run for office. We also undertook unstructured interviews with some of the consultants and candidates involved, and conducted a national survey of the organisation’s 2,083 alumnae for more details, see Bernhard, Shames, and Teele (Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021) and Shames, Bernhard, Holman, and Teele (Reference Shames, Bernhard, Holman and Teele2020). This approach allows us to witness women in the process of deciding whether to run for political office. Notably, only 51 per cent of the participating women ultimately choose to pursue political office, despite undergoing months of training and incurring substantial costs. This variation in decision-making among women is crucial to understanding the dynamics involved.

The training sessions we observed took place during the 2014–2015 and 2015–2016 cohort years, each consisting of approximately 45 women with diverse backgrounds in terms of ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, age, and prior political experience. While the three programme staff remained constant across both cohorts, there was considerable demographic diversity in the characteristics of the pools of political consultants and participants. Ten per cent of participants identified as Asian American and Pacific Islander, 20 per cent as Black or African American, 36 per cent as Non-Hispanic White, 23 per cent as Hispanic/Latina, and 11 per cent as Other or Multiracial. Eighty-seven per cent also identified as straight, 10 per cent as LGBTQ, and 3 per cent declined to say or were missing data. Their ages spanned from 31 to 64 (median 41).Footnote 12 Finally, 45 per cent were single or divorced, 52 per cent married or partnered, and 3 per cent declined to say or were missing data (for more on why this might matter, see Bernhard et al., 2018).

Although the specific training topics varied slightly each year, the sessions generally covered public speaking, media, and messaging; fundraising; networking and endorsements; campaign strategy; field operations; ethics; and considerations of diversity. A typical training day involved workshops focusing on one of these topics, with two to three sets of consultants delivering presentations, alumnae providing the ‘elected’ graduates’ perspective, and interactive activities such as practice pitches and fundraising call simulations. Trainees engaged in Q&A sessions during each session and socialised during meals and networking events.

The Emerge programme, hosted annually, is demanding, spanning six months and incorporating around 70 hours of training, primarily through full weekend workshops.Footnote 13 The daily schedule is also demanding, with Saturday training sessions often extending from 9 AM to 9 PM, excluding informal socialising afterward. Weekend ‘boot-camps’ include evening events for networking and practicing fundraising skills.

Our informal interviews with trainees occurred during breaks or over meals, while more formal interviews with programme staff were typically scheduled in advance and often conducted over the phone. After the second programme year in May 2016, we collaborated with the organisation to administer a national survey to all alumnae, consisting of approximately 20 minutes of questions covering demographics, detailed quantitative measures of potential barriers to office (such as childcare responsibilities), and open-ended inquiries about their decision-making process regarding running for office (for more information, see Bernhard et al., 2018; Shames et al., Reference Shames, Bernhard, Holman and Teele2020).

Survey and Experimental Data

Our final dataset is derived from surveys we have run asking people about their perceptions of various jobs and elected offices. We provide details on the general data collection process here and describe questions in more detail in each section before we present the results.

In our online survey, run through the LUCID Fulcrum platform, we asked 1,579 Americans a variety of questions about occupations (described below), offices (described in Section 4), and the electability of people from different occupations for a variety of local offices (also discussed in Section 6).Footnote 14 The study sample was designed to be approximately representative of the US population on gender and race/ethnicity: 50.6 per cent of respondents were women and 0.3 per cent selected other or declined to state. Approximately 72 per cent identified as white, 12 per cent as Black, 5 per cent as AAPI, 10 per cent as Native American, multiracial, or other, and 0.3 per cent declined to answer.

Drawing on work by Valentino (Reference Valentino2021) and measures regularly asked on the General Social Survey, we asked respondents the following question as a measure of occupational prestige:

Where would you place each occupation in terms of its social standing? Please select 9 if you think that occupation has the highest possible social standing. Select 1 if you think it has the lowest possible social standing. If it belongs somewhere in between, just select the level that matches the social standing of the occupation.

Respondents rated 10 of the same Census list of 540 occupations we described in the last section. This means we have ratings of hundreds of different occupations, from ‘Airplane Mechanics’ to ‘Farm Laborers’ to ‘Yarn Spinners’.

Then, drawing on work by Bittner and Goodyear-Grant (Reference Bittner and Goodyear-Grant2017) and Kreitzer and Watts (Reference Kreitzer and Watts2018), we asked the respondents to assess the same ten randomly chosen occupations on their perceived femininity using the following scale:

Some occupations in society are seen as more feminine, while others are seen as more masculine. Below you will find a continuum that goes from left to right. We would like you to place each occupation somewhere along this scale: the far left of the scale reflects an occupation that you feel is 100% masculine, while the far right of the scale reflects an occupation that you feel is 100% feminine. Where would you place this occupation on this continuum? (0–100, where 0 represents occupations that are 100% masculine and 100 represents occupations that are 100% feminine).

Respondents were randomly assigned to either rate the prestige of the jobs first, or the femininity of the jobs first. We did not see any clear effect of question order, so we simply use all the data without a fixed effect for question order.

Taken together, these datasets allow us to describe at a fine-grained level who runs for and wins office as a function of their gender and occupation.

3 Gendered Occupational Segregation Shapes Who Runs and Wins Local Office

All of the strong character traits [for politics] are masculine. That’s where we get stuck.

Our first empirical section answers a key question: compared to the general population, who runs for office and who wins? The data and methodological challenges we outline in Section 2 mean that it has been hard to study patterns of gendered occupations and candidate emergence at the local level; we offer new data to fill this gap. We begin by reviewing existing work on how gender shapes political ambition, and then how occupation shapes candidate emergence. Within each of those sections, we provide a view of the distribution of political candidates by gender and professional sector to see how these two factors shape who runs and who wins.

Gender and Ambition

From girls in elementary school to college students to ‘ordinary women’ to women with elite backgrounds, women are less interested in a political career, in running for office, or in holding office (Bernhard et al., Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021; Bos et al., Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2021; Crowder-Meyer, Reference Crowder-Meyer2020; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016; Wolbrecht & Campbell, Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007). The gap between women and men in interest in political office can be traced to a wide set of causes, including gender role socialisation, risk and conflict avoidance, gender biases of voters and political leaders, and the patriarchal and gendered nature of political opportunity.

As we discussed in Section 1, socialised gender roles push women towards communal goals and activities—ones that serve others and express care and concern—and men towards agentic goals and activities – ones that primarily serve the individual and express decisiveness and independence. Because political office is seen as fulfilling agentic roles (Okafor, Reference Okafor2017; Rudman & Phelan, Reference Rudman and Phelan2008; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Bos and DiFilippo2022) and requiring agentic skills (Holman et al., Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2022; Sweet-Cushman, Reference Sweet-Cushman and Bauer2020a; Reference Sweet-Cushman2021), women’s gender socialisation pushes them towards activities like non-profit leadership and volunteering over seeking political office. And voters, who have been socialised in the same system, hold women seeking political office to particularly high standards because their gender is incongruent with seeking a political leadership role.

The association of men with leadership roles leads to a mismatch between views of the skills and expertise that women have and our expectations for our leaders. This ‘double-bind’ is particularly powerful for women seeking political roles: women politicians lose the positive attributes women are generally stereotyped as having, like warmth and empathy, but don’t gain the positive attributes men are stereotyped as having, like assertiveness and confidence (N. M. Bauer, Reference Bauer2020a; Schneider & Bos, Reference Schneider and Bos2014). As a result, women must engage in work to demonstrate they are capable of leadership (being strong leaders, for example), and simultaneously avoid giving voters the idea that they are not capable of doing work that women should be good at, such as working with others. One consequence of this is that women often seek out offices where the expectations of ‘masculine’ behaviour are lower, such as school boards, city clerks, and secretary of education (Anzia, Reference Anzia2022; Crowder-Meyer, Reference Crowder-Meyer2013; Fox & Oxley, Reference Fox and Oxley2003).

Women are also excluded from many of the important political networks that guide recruitment into political office and facilitate access to resources necessary to succeed as a political candidate (Barber et al., 2016; Crowder-Meyer, 2013; Thomsen & Sanders, 2020). The adage that ‘it’s not what you know, it’s who you know’ is particularly true in local politics, where political networks are insular and dependent on the activities of central leaders like political party chairs (Butler & Preece, Reference Butler and Preece2016; Crowder-Meyer, Reference Crowder-Meyer2013). As a result, women must be ‘self-starters’ to run for office: seeking opportunities without strong encouragement from others. This entrepreneurial spirit—and the ability to access resources needed to run—is associated with agentic traits, career choices, and risk tolerance, leading to gender gaps in who is willing to engage in such activities (Sánchez & Licciardello, Reference Sánchez and Licciardello2012; Thébaud, Reference Thébaud2010, Reference Thébaud2015). One consistent result is that women are less likely to sort into careers that require entrepreneurial effort or to seek out local political opportunities.

Women Run for Offices That They Can Win

Running for office is inherently risky: one is spending time, money, family resources, connections, and personal capital on an outcome that is rarely guaranteed. Women avoid risk and conflict generally and electoral conflict specifically (Friesen & Holman, Reference Friesen and Holman2022; Kanthak & Woon, Reference Kanthak and Woon2015; Preece & Stoddard, Reference Preece and Stoddard2015; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016),Footnote 15 making political ambition particularly unlikely for women. Given that these risk and conflict preferences also shape individual choices about their careers and their positions within occupations (Canary, Cunningham, & Cody, Reference Canary, Cunningham and Cody1988; Thébaud, Reference Thébaud2010) those individuals who select careers with few conflicts might also be less interested in running for office. For example, someone might seek out a teaching career because the job is seen as stable, with reliable health insurance and retirement income; that same person may be less interested in running for office because they see it as a risky enterprise.

Women, particularly politically ambitious women, are also highly rational political actors. Because women who run for office are interested in winning, they run where they believe that they will be able to win (Anzia & Bernhard, Reference Anzia and Bernhard2022; Bernhard et al., Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021; Ondercin, Reference Ondercin2022; Shames et al., Reference Shames, Bernhard, Holman and Teele2020). For example, Ondercin (Reference Ondercin2022) finds that women running for Congressional offices in the United States are much more likely to emerge as candidates when the district’s characteristics have helped women get elected in the past. Some of this relates directly to women’s perceptions that the political system is biased against women generally (N. M. Bauer, Reference Bauer2020b; Teele, Kalla, & Rosenbluth, Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018); as a result, women often wait until they are more qualified to overcome any potential biases (Fulton et al., Reference Fulton, Maestas, Maisel and Stone2006; Kanthak & Woon, Reference Kanthak and Woon2015; Shames et al., Reference Shames, Bernhard, Holman and Teele2020).

Another consequence of women’s strategic activity is that women often run for specific offices where they believe they are more likely to be elected, such as school board and city clerk (Anzia & Bernhard, Reference Anzia and Bernhard2022; Crowder-Meyer et al., Reference Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian and Trounstine2015; Fox & Oxley, Reference Fox and Oxley2004) and even highly accomplished women do not believe they are qualified to run for political office. These are also self-reinforcing systems, where women see more women in offices like school board and then run for those specific offices because the office is seen as better aligning with women’s goals. These patterns are also different across gender and race, so the factors that shape white women’s emergence as candidates do not necessarily apply to women of colour (Fraga, Gonzalez Juenke, & Shah, Reference Fraga, Gonzalez Juenke and Shah2020; Holman, Reference Holman, Brown and Gershon2016a; Silva & Skulley, Reference Silva and Skulley2019).

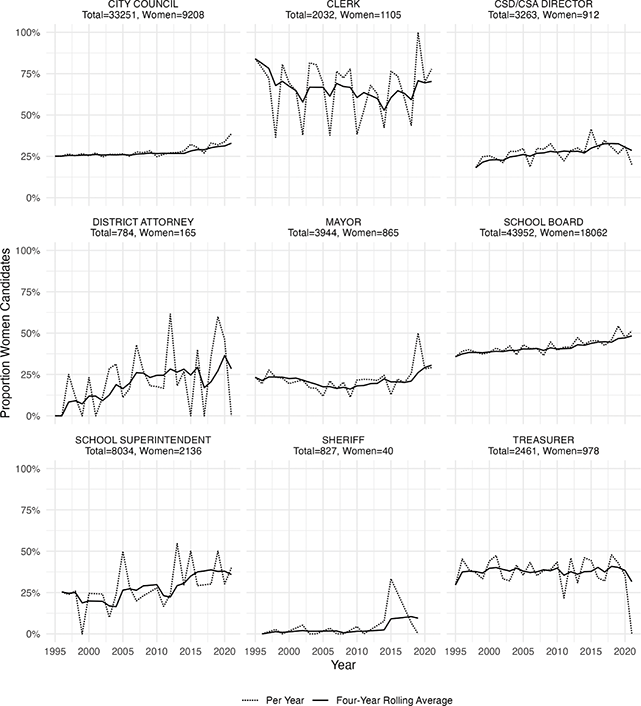

Our observational data is consistent with these predictions: as Figure 3 shows, women are much more likely to run for some offices than others. The places where women run at higher levels are consistent with stereotypes about women’s gender roles, like clerk and school board, and much less likely to run for offices inconsistent with those roles, like sheriff and police chief.

Figure 3 The share of women candidates varies across different local offices. As with occupations, women are much more likely to run for some offices than others.

Moreover, despite rhetoric about women’s progress towards equality in society (and women’s increased educational attainment and work outside the home), the share of women candidates has stayed the share of women candidates has stayed constant or only slightly increased over the twenty-six years for which we have data, as shown in Figure 4. Notably, for almost all offices, the variation in the percentage of candidates for that office who are women is much larger across offices than within offices over time.

Figure 4 The share of women as candidates over time by local office. The number of women candidates has slightly increased over time, but only in some offices.

We can see that there is only a slight increase over time in the number of women running for city council, community services director, mayor, and sheriff. There are more substantial increases in the number of women running for district attorney, school board, and school superintendent. There is little to no increase, or even a decrease, in the number of women running for clerk and treasurer. In the earliest years of the data, women tended to run in high numbers only for feminine-stereotyped roles like clerk and school board, but as time has gone on, more women have acquired the skills, networks, and resources to run for positions like district attorney. And while the absolute numbers are still very low, we can start to see a measurable number of women running for extremely masculine-stereotyped roles like sheriff, where previously there were zero women candidates in many years (for discussion see Farris & Holman, Reference Farris and Holman2024).

Voting and Elections in Local Politics

While much of what we know about gender and politics has focused on national or state politics, we can learn from the scholarship on voting and elections in local politics to understand women’s exclusion. What we do know is that low information about local elections represents one important obstacle to women’s ability to access political office. Broadly, voters are often uninformed about local politics, with few opportunities to remedy their lack of information (Bernhard & Freeder, Reference Bernhard and Freeder2020; de Benedictis-Kessner, Reference de Benedictis-Kessner2017; Schaffner & Streb, Reference Schaffner and Streb2002; Trounstine, Reference Trounstine2013). This is particularly true when elections are local elections where election dates are more likely to be ‘off-cycle’ (that is, not aligned with Congressional or presidential elections), non-partisan, and for more obscure offices like sheriff and city clerk (Crowder-Meyer et al., Reference Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian and Trounstine2015; de Benedictis-Kessner, Reference de Benedictis-Kessner2017; Farris & Holman, Reference Farris and Holman2023a).

There is reason to believe that the gender stereotypes that we discuss in Sections 1 and 2 would apply more strongly at the local level. The little information that voters have about local offices leads to the reliance on information shortcuts—cues—that replace more complete information (Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian, & Trounstine, Reference Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian and Trounstine2019; Holman, Merolla, & Zechmeister, Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2017; Kreiss, Lawrence, & McGregor, Reference Kreiss, Lawrence and McGregor2020; McDermott & Panagopoulos, Reference McDermott and Panagopoulos2015). Gender is one of the most central and available information shortcuts available to voters, particularly in the context of non-partisan elections (Badas & Stauffer, Reference Badas and Stauffer2023).

Occupation and Candidate Emergence

What about the occupations of candidates? While the influence of one’s job on one’s status, life expectancy, earnings, and experiences are well documented (i.e., Friedman & Laurison, Reference Friedman and Laurison2019), less is known about how occupation interacts with gender to shape pathways to and experiences of political candidacy. Work on political class as measured by occupation often focuses on how those from blue-collar backgrounds (such as coming from unions or jobs that require physical labour like agricultural work) behave in political office (Barnes & Holman, Reference Barnes and Holman2018, Reference Barnes and Holman2020b; J. H. Kim, Kuk, & Kweon, Reference Kim, Kuk and Kweon2024), or the sorts of criteria voters use to evaluate candidates, including their occupations and military service (Atkeson & Hamel, Reference Atkeson and Hamel2020; Coffé & Theiss-Morse, Reference Coffé and Theiss-Morse2016; Kirkland, 2020; McDermott, Reference McDermott2005; McDermott & Panagopoulos, Reference McDermott and Panagopoulos2015; Mechtel, Reference Mechtel2014).Footnote 16 But while scholarship explores how employment shapes political participation (for example, see Aalen et al., Reference Aalen, Kotsadam, Pieters and Villanger2018; Greenberg, Grunberg, & Daniel, Reference Greenberg, Grunberg and Daniel1996; Iversen & Rosenbluth, Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2008; Kjelsrud & Kotsadam, Reference Kjelsrud and Kotsadam2023; Schlozman, Burns, & Verba, Reference Schlozman, Burns and Verba1999), very little explores the effects of either specific occupations on political engagement or how occupations might affect candidate emergence specifically. While no single existing theory exists as to why some professions might be more likely to select into and out of politics, we briefly review the most relevant work below.

Occupational Prestige, Class, and Wealth

Why might occupation matter to voters? Most obviously, it matters because voters want candidates to be competent to handle the ‘portfolios’ of their offices. For instance, voters see candidates with business backgrounds as better equipped to handle economic issues, and those with education backgrounds, human services issues (Campbell & Cowley, Reference Campbell and Cowley2014; Coffé & Theiss-Morse, Reference Coffé and Theiss-Morse2016); voters also see working-class women as particularly unsuited for political office (HJ. Kim & Kweon, 2024). Perhaps because this has seemed like such a no-brainer, there is surprisingly little work directly exploring how specific candidate occupations shape voting, though a large body of work does exist that explores how much occupational background matters to voters at the ballot box, for example, due to its use as a heuristic in low-information elections (McDermott, Reference McDermott2005; Mechtel, Reference Mechtel2014). Instead, candidate occupation frequently operates ‘invisibly’ in studies of elections, serving as a control variable when political scientists can get such data (e.g., Anzia & Bernhard, Reference Anzia and Bernhard2022).

Occupations also might matter to voting in ways beyond the issue or domain competence they signal. Occupational prestige shapes interpersonal relationships, political attitudes, and social power as it ‘explicitly represents social standing’ (Fujishiro et al., Reference Fujishiro, Xu and Gong2010, 2100). Because occupational prestige shapes so many components of social exchanges, it also links to individual and group-based outcomes like civic participation, marriage, and health (Fujishiro et al., 2010; Kalmijn, Reference Kalmijn1994; Kitschelt & Rehm, Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014; Sobel, Reference Sobel1993). While higher occupational prestige is associated with higher pay and more education or training requirements, these materialistic characteristics do not entirely explain an occupation’s prestige. Instead, ‘the typical sex or race of a class of jobs in workplaces becomes a fundamental aspect of the jobs, influencing the work done as well as the organisational evaluation of the worth of the work’ (Tomaskovic-Devey, Reference Tomaskovic-Devey2019, p. 6). Previous work suggests more feminine jobs are seen as less prestigious jobs, including over time: as women become the majority of workers in a previously male-dominated occupation, that occupation is then seen as less prestigious (Busch, Reference Busch2020; Levanon, England, & Allison, Reference Levanon, England and Allison2009).

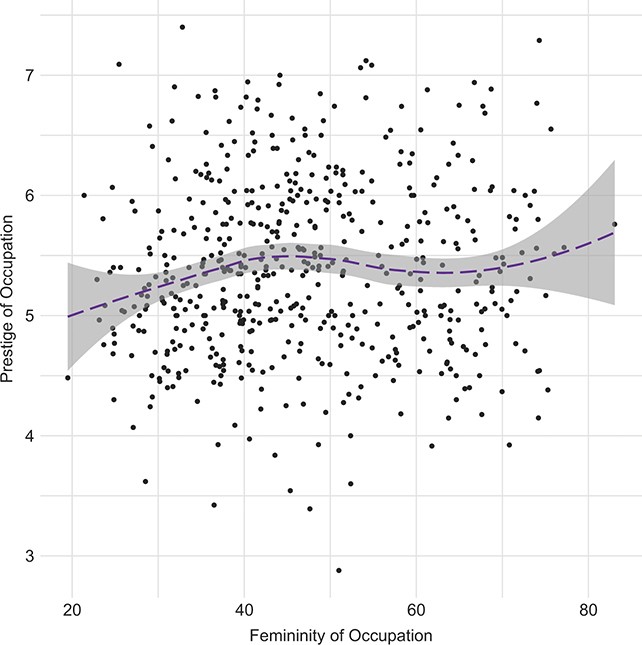

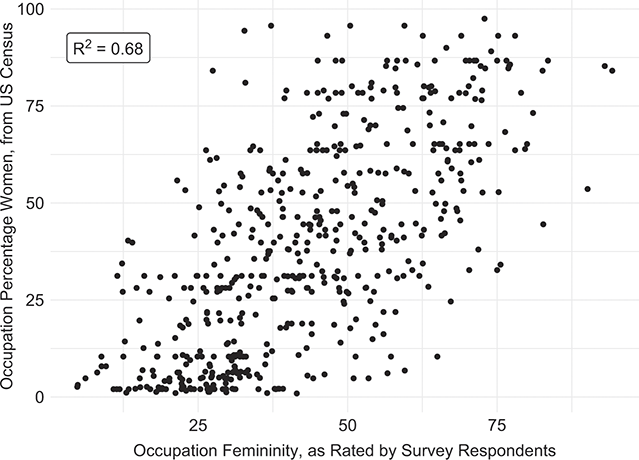

Yet even as political scientists have implicitly focused on occupational prestige (Barnes & Holman, Reference Barnes, Holman, Thomas and Franceschet2023; O’Grady, Reference O’Grady2019) or the role of specific occupations (Bonica, Reference Bonica2020; Kirkland, Reference Kirkland2020), we know much less about how occupational prestige and perceptions of occupation as feminine influence political ambition and candidate success. Interestingly, in Figure 5, we see surprisingly little relationship between perceptions of how female-dominated and how prestigious an occupation is. (We will come back to the issue of occupational prestige in Section 4 when we look to see how real elections play out.) For instance, telemarketers are rated as the lowest prestige job in the dataset, but the perceived gender balance is nearly equal at 51 out of 100 on the masculine-feminine scale. Aircraft pilots and nurse practitioners are rated near the top for prestige, but pilots are masculine-coded (33 out of 100) and nurses, feminine-coded (74 out of 100).

Figure 5 Perceived occupation femininity and prestige do not appear to be closely related. 540 Census occupations were rated on both dimensions by survey respondents.

One reason we may not see a stronger relationship between prestige and masculinity here is because the Census occupations that respondents rated are very specific. For instance, nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, nurse anaesthetists, registered nurses, and vocational nurses are all separate categories. So even though each occupation is rated approximately thirty times (by thirty respondents), respondents may have quite a bit of uncertainty about how prestigious these specific occupations are relative to one another.

Class is separate from (but directly related to) perceptions of occupational prestige. While scholars have extensively debated the ways and means of measuring class (A. K. Cohen & Hodges, Reference Cohen and Hodges1963; Friedman & Laurison, Reference Friedman and Laurison2019; Friedman, Laurison, & Miles, Reference Friedman, Laurison and Miles2015; Rubin & Rubin, Reference Rubin and Rubin1987), many researchers focus on occupational-based measures (O’Grady, Reference O’Grady2019), including identifying jobs that do not require a college degree as working class and focusing on ‘blue-collar’ and ‘pink-collar’ occupational classifications (Barnes, Beall, & Holman, Reference Barnes, Beall and Holman2021; Barnes & Holman, Reference Barnes, Holman, Thomas and Franceschet2023; Mastracci, Reference Mastracci2004; Norris & Lovenduski, Reference Norris and Lovenduski1995; Royster, Reference Royster2003). Despite class shaping the preferences and behaviours of candidates and those elected to political office (Barnes, Kerevel, & Saxton, Reference Barnes, Kerevel and Saxton2023; Grumbach, Reference Grumbach2015; J. H. Kim, Kuk, & Kweon, Reference Kim, Kuk and Kweon2024), evaluations of class advance an implicitly gendered definition of what it means to be a member of the working class (Carnes, Reference Carnes2018), a point discussed in detail by Barnes et al. (Reference Barnes, Beall and Holman2021). And, evaluations of women’s representation have largely ignored class, despite discussions of women’s policymaking preferences being deeply rooted in the feminisation of poverty (Clayton & Zetterberg, Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2018; Holman, 2014, Reference Holman2015). Childs and Hughes (Reference Childs and Hughes2018) and R. Murray (Reference Murray2023) offer two exceptions, exploring the extent to which elite and upper-caste women make up representative bodies around the world. Another exception is Campbell & Cowley (Reference Campbell and Cowley2014), who find that voters are turned off by ultra-wealthy candidates. Yet here, too, we know little about the connection between class and candidate emergence, beyond recognising that class and its correlates, like wealth and education, strongly predict who holds power in systems around the world.

Finally, occupational prestige is not only linked to class but wealth. There is of course an enormous body of work on the influence of money in politics (e.g., Gilens, Reference Gilens2012; Winters, Reference Winters2011), with a smaller subset focusing on individual and household wealth (Carnes, Reference Carnes2018; Gilens, Reference Gilens2012), including on gender (e.g., Bernhard et al., Reference Bernhard, Eggers and Klašnja2024). For our purposes, we are less interested in the material aspects of occupations (although they are clearly important to shaping an individual’s access to the resources necessary to run office); instead, we simply note here that in our data, we cannot disentangle the ‘effects’ of wealth (or class) from those of occupation. We hope that future work will explore these distinctions, for instance by finding ways to hold wealth constant while varying occupational prestige.

Drawing these bodies of literature together, we argue that one important and understudied set of factors is how gender and occupation influence who chooses to run for office and who is selected by voters. In the next section, we test this argument by analysing the shifts in the gender and occupation makeup of each group, starting with the general population and then looking at candidates and election winners.

From Population to Candidates to Leaders: Candidate Emergence by Occupation and Gender

So, who runs and who wins? In the top pane of Figure 6, we show the dramatic patterns of selection into (or out of) politics by industry. Some sectors like construction represent a large part of the workforce (22 per cent) but tend to produce very few candidates for office (just 5 per cent of candidates and 6 per cent of winners). Other industries like education, law, and protection produce many more candidates than their share of the population. The ratio of the population to candidates and winners here is meaningful: for the population, there are more than five times the number of lawyers in the candidate pool as there are in the general population, and three times the number of businesspeople. In comparison, office workers and construction workers make up just one-fifth of the share of candidates relative to their share of the general population. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s career as a bartender before running for Congress stands out here: while food service workers make up more than 5 per cent of workers, they are only 0.03 per cent of candidates and 0.02 per cent of elected leaders. This is notable, because, as Rep Ocasio-Cortez noted on Twitter: ‘Bartending + waitressing (especially in NYC) means you talk to 1000s of people over the years. Forces you to get great at reading people + hones a razor-sharp BS detector.’

Figure 6 Business and education are the largest categories among candidates and winners, but not among the population. Population data from the American Communities Survey for California; candidate and elected leaders data from CEDA database, coded by authors, and excludes incumbents.

But these patterns are not just about occupations, but also about gender. We know that gender segregation of occupations is very powerful and this reveals itself in the middle and bottom pane of the figure. Among men, there is substantial self-selection into politics among those in business, education, and protection-related careers, and substantial self-selection out of those in construction roles, which is the most common category of jobs among men. Among women, there is still substantial self-selection into politics from business, slightly less so for education, and substantial self-selection out of politics for those in office and administrative work (the most common category of jobs among women).

Education also stands out for both men and women. As we discuss in detail in Section 6, men from education backgrounds self-select into politics at a much higher rate than we see in the general population: only 4 per cent of men in the population work in education, but more than 14 per cent of male candidates and 17 per cent of male winners work in education (a three-to-one ratio for candidates and a four-to-one ratio for winners). Women educators are also overrepresented, but at a lower rate: a two-to-one ratio for candidates and a five-to-two ratio for winners.

We also present this data within broader feminine and masculine categories in Table 1. Here, we focus on the difference in the population share and the share of candidates and winners within each gender. Feminine occupations are those like education and office administration where women make up more than 60 per cent of the workforce in the occupation; masculine occupations follow as occupations dominated by men (Barnes & Holman, Reference Barnes and Holman2020a). We also include a ‘neutral’ category that includes occupational categories like sales and food preparation, where women and men make up similar portions of the occupation.

Table 1 Men with feminine occupations and women and men with masculine occupations are overrepresented as candidates and winners, compared to their share of the population.

| Both Genders | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cand. | Winner | Cand. | Winner | Cand. | Winner | |

| Feminine careers | 0.84 | 1.01 | 0.77 | 0.88 | 1.23 | 1.45 |

| Masculine careers | 1.49 | 1.45 | 1.92 | 1.83 | 1.23 | 1.24 |

| Neutral careers | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.44 |

US Census and CEDA data. Ratios above 1 mean an increased probability of individuals in a given career running for or winning office relative to their population percentage; ratios below 1 mean a decreased probability.

How does the representation of feminine, masculine, and neutral occupations in the population compare to candidates and elected representatives? In Table 1, a number under one indicates that the group is better represented in the general population than among candidates and winners. A number over one means that the group is better represented among candidates or winners than in the general population. For example, when we look at feminine careers for all candidates (first row and column of data), the 0.84 figure means that for every ten people in the general population who have a feminine occupation, roughly eight people with feminine occupations become candidates—and then ten will become winners (1.01), meaning that candidates from feminine careers win at higher rates than they appear as candidates. In comparison, the ratio of 1.49 for masculine careers and candidates (column one, row two) indicates that for every ten people in the general population with a masculine career, there are nearly fifteen (1.49) candidates and fifteen (1.45) winners.

Three patterns stand out in Table 1. We start with the finding that women with feminine careers (row one) are underrepresented in political office, while men from feminine occupations are overrepresented compared to their share of the population. Both men and women from feminine careers are better represented among winners than among candidates, but even voter preferences for women from feminine backgrounds do not overcome the supply issue. Second, the most reliably overrepresented group are masculine careers. This is especially true for women from masculine careers, where women from masculine occupations are nearly twice as likely to enter as the share of candidates as compared to their share in the population. And, third, while gender-neutral occupations make up more than 20 per cent of those in the workforce, this group selects out of politics and voters are less likely to select them compared to their share on the ballot.

In this section, we explored how gender and occupation shape engagement with the political system. We presented original data showing how well a broad set of occupations are descriptively represented among candidates and winners across all local political offices. Our analysis revealed that occupational gender segregation helps produce the occupational gender segregation of political candidates and winners. Moving forward, we consider how the alignment between the role of political leader and occupational femininity/masculinity shape who runs and wins local office.

4 Gender-Segregated Jobs Influence Perceived Occupational Femininity and Win Rates

People like women in helping professions, not in traditional seats of power like CEO.

If you’re in any way male or masculine, you are advantaged in life and in politics.

If you close your eyes and picture an elementary school teacher, what does that person look like? What about when you imagine a police officer? For most Americans, the image these occupations generate—a friendly woman working as an elementary school teacher, or a stern man working as a police officer—is heavily influenced by the gender distribution of those who work in the occupation. In fact, 80 per cent of elementary school teachers are women and 77 per cent of police officers are men.

The lives of women in advanced industrialised nations have changed enormously over the last half a century. Women have become nearly half of all wage earners and make up the majority of college graduates, new lawyers, and more than half of the managers of the US workforce. Yet, even as these dramatic shifts have occurred, the gender distribution of occupations has not shifted in large ways (Barnes & Holman, Reference Barnes, Holman, Thomas and Franceschet2023; Guy & Newman, Reference Guy and Newman2004; Roos & Reskin, Reference Roos and Reskin1984). For example, in 1990, 82.5 per cent of elementary school teachers were women. It is not just teachers and police officers, either: in 1991, 93 per cent of nurses and 8 per cent of engineers were women. In 2020, little had changed: women held 91 per cent of nursing jobs and 14 per cent of engineering positions. Nursing, teaching, law enforcement, and engineering are not anomalies: more than half of the workforce in the United States are employed in gender-segregated occupations (Busch, Reference Busch2020). A full 53 per cent of women in the United States would have to shift into a currently male-dominated occupation to eliminate gender segregation in the workforce (Levanon & Grusky, Reference Levanon and Grusky2016). Scholars note that the prospects of reducing the ‘remarkable persistence’ of gender segregation of occupations ‘remain slim’ (P. N. Cohen, Reference Cohen2013). The United States is not alone: while research on gendered segregation in occupations has often focused on the United States and Europe (Elsässer & Schäfer, Reference Elsässer and Schäfer2023; Razzu & Singleton, Reference Razzu and Singleton2018), recent work shows that gendered segregation in occupations and sectors is increasing in the developing world (Borrowman & Klasen, Reference Borrowman and Klasen2020).