1 Africa’s Aspirations to Industrialize and the Role of China: Questions and Premises

Since the early 2000s, Chinese engagements in AfricaFootnote 1 have grown at an unprecedented rate. Trade has expanded from $10bn in 2000 to $262bn in 2023, making China Africa’s largest partner.Footnote 2 Meanwhile, China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) stock in Africa has grown from $500mn in 2003 to over $40bn in 2023, reaching a peak of $46bn in 2018. Chinese funding for infrastructure and the contract revenues of Chinese construction companies in Africa have also risen many times over. These developments have coincided with a rollercoaster of macroeconomic trends in African countries, from the commodity boom of the 2000s to the effects of the global financial crisis, from the expansion in debt to the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Driven by these contradictory forces, African economies have shown wide variations in economic performance, although the pending task of structural economic transformation looms large across most of the continent.

Only a very small number of African countries have managed to achieve a significant degree of industrialization. Nevertheless, recent years have seen a revival of industrialization aspirations, partly driven by Asian success stories and partly by growing discontent at the Western aid-led focus on market liberalization and ‘good governance’ reforms. This revival has been supported by the leverage and strategic ‘triangulation’ that China’s growing engagement in Africa has offered (Large Reference Large2021). There are important historical antecedents in the postcolonial period for China’s presence in Africa’s infrastructure and manufacturing development, such as the large import-substituting West Africa Textiles investments in Nigeria or the famous Tazara Railway connecting Zambia and Tanzania (Sun Reference Sun2017; Shinn Reference Shinn, Oqubay and Lin2019). What has changed, however, is the scale of China’s engagement and its unprecedented growth. This multifaceted phenomenon has recently been analysed through the conceptual lens of ‘Global China’. According to Lee (Reference Lee2022) and Franceschini and Loubere (Reference Franceschini and Loubere2022), ‘Global China’ can be defined in different ways depending on the focus of analysis: as a policy framework; as a power project consisting of economic statecraft, patron–client relations and symbolic domination; or as a method of analysis for understanding China’s globalization and its various manifestations. As such, ‘Global China’ consists of multiple actors with varying interests (Taylor Reference Taylor, Oqubay and Lin2019), sometimes in fierce competition with one another, and always subject to bargaining and contestation from a variety of African state and non-state actors.

This is not the first time questions concerning China’s impact on Africa’s industrialization have been posed. As noted by Wolf (Reference Wolf2016), there is a narrative contrast between: (a) studies (e.g. Kaplinsky Reference Kaplinsky2008) emphasizing the negative impacts of China’s engagement on Africa’s manufacturing due to a flood of cheap imports affecting local manufacturers, especially after African markets liberalized since the 1980s and China joined the WTO in 2001; and (b) research focusing on the opportunities China’s industrial upgrading generates for FDI-led light manufacturing development in Africa, as Chinese manufacturers move overseas (Lin Reference Lin2018; Geda et al. Reference Geda, Senbet and Simbanegavi2018; Calabrese and Tang Reference Calabrese and Tang2023). The former, pessimistic, view is influenced by the reality that Africa’s manufacturing lacks competitive advantage vis-à-vis Asian exporters (not just China), and remains overly exposed to competition given the very liberal trade regimes prevalent in most African countries since the structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) of the 1980s. By contrast, more realist, optimistic accounts apply Hirschman’s ‘possibilist’ lens and historical evidence that countries can develop productive capabilities against the odds, overcoming obstacles and pain (Cramer et al. Reference Cramer, Sender and Oqubay2020). But is industrialization really desirable or feasible in Africa? And how can be achieved?

1.1 Industrialization in Africa: Why, How, Where, and When?

There are various arguments promoting Africa’s structural transformation, with the point of contention generally around which path to take and whether industrialization is a necessary component. Here, one initial question to ask is: Why industrialize? Desirability does not necessarily imply viability, however – structural transformation needs to be built, often over extended periods of time and in the face of various obstacles, which leads to a second question: How best to industrialize? These interrelated questions have spawned an extensive literature, summarized next. In doing so, the Element draws on the work of selected political economists working on structural change and industrialization in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Hirschman, Amsden, Chang, and, more recently, Cramer et al. (Reference Cramer, Sender and Oqubay2020), Hauge (Reference Hauge2023), and Whittaker et al. (2020). These authors defend the ‘art of the possible’, arguing that even lowest-income countries can aspire to industrialize based on the previous experiences of early and late developers, the opportunities they seized, and the panoply of industrial policy tools they deployed. While lessons from the past are critical, important shifts (e.g. climate change, new geopolitical shocks, technological change) that may have created context-specific opportunities to leapfrog stages of structural transformation must also be taken into account.

There are two relevant sets of classic arguments arising from a heterodox development economics tradition. First are the ‘Kaldor laws’, which refer to the symbiotic relationship between manufacturing growth and scaling up on the one hand, and economy-wide productivity growth on the other. This is driven by increasing returns to scale in manufacturing, as well as the sector’s particular properties, which make it a hub for technological change (in terms of both innovation and diffusion). These ‘laws’ have been repeatedly tested by empirical work applied to different country samples and time periods, demonstrating there is indeed a symbiotic relationship between manufacturing development and sustained economic and productivity growth (Thirlwall Reference Thirlwall2013; Hauge Reference Hauge2023; Cramer et al. Reference Cramer, Sender and Oqubay2020).

Second, Hirschman’s work expands on manufacturing’s strong growth and transformative properties by stressing the strong productive linkages – both backward and forward – generated in other sectors, such as cotton for textiles, business services and logistics, and multiple intra-industrial linkages that contribute to the expansion of industrial eco-systems (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1958). In short, the development of manufacturing capabilities generates demand, new markets and technological opportunities for various other economic activities, from agriculture to transport to trade to other modern services.

Employment matters too, especially for countries experiencing population growth and a youth bulge, as is the case across much of Africa. Thus, if the Kaldor laws and Hirschman’s productive linkages hold, industrialization can also be an engine for the mass creation of direct, indirect and induced jobs. As argued by Amsden (Reference Amsden2012), only the emergence of larger-scale, more technologically capable employers able to make long-term investments supportive of mass job creation can help African workers escape the trap of risky, low-return self-employment. Here, the employment multiplier effect of manufacturing is very high, as every new job in the sector holds the potential for 3–4 additional jobs being created elsewhere in the economy as an indirect outcome (Cramer et al. Reference Cramer, Sender and Oqubay2020, 101).

Another relevant argument is that more diversified, industrial-led export growth – buttressed by inter-sector linkages – can contribute to a relaxing of balance-of-payments constraints, which for many low-income countries (LICs) are a key impediment to growth (Thirlwall Reference Thirlwall2013). More foreign exchange availability can in turn facilitate further structural transformation into other higher-value added sectors (Cramer et al. Reference Cramer, Sender and Oqubay2020).

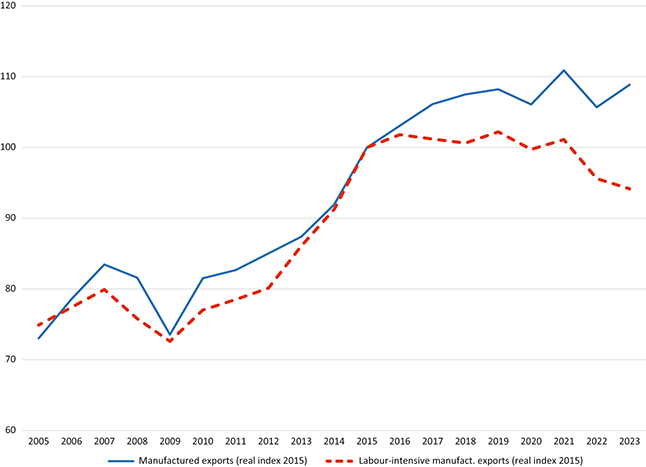

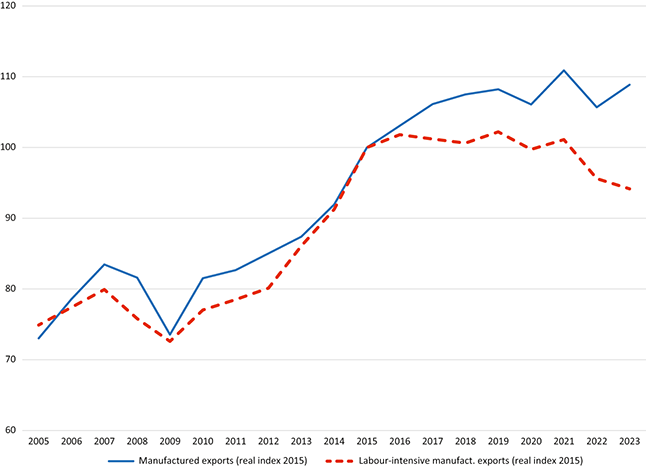

Despite growing doubts over the viability of industrial-led transformation, and despite consideration being given to services acting as a ‘substitute’ (Rodrik and Sandhu Reference Rodrik and Sandhu2024), the available evidence for the current era of so-called ‘premature deindustrialization’ (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2016) suggests that manufacturing production and employment have actually continued to expand globally. Here, it should be noted that although the manufacturing’s global employment share has not significantly changed (Haraguchi et al. Reference Haraguchi, Cheng and Smeets2017), the sector continues to attract a large and growing share of greenfield FDI (UNCTAD 2024). Moreover, even labour-intensive manufacturing exports have experienced rapid growth since 2000 (Figure 1; Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Mensah, Sen and De Vries2023). This is even considering the fact that sector classifications fail to fully recognize the significance of manufacturing, given how much of what counts as ‘services’ is deeply connected to industrial production worldwide (Hauge Reference Hauge2023; Cramer et al. Reference Cramer, Sender and Oqubay2020). Thus, despite the rapid growth of services across different country income categories, manufacturing is far from a stagnant or declining sector. It is also clear – hence some of the pessimism in both high-income countries (HICs) and LICs – that there has been a reconfiguration of global manufacturing output, with China growing its share continuously, together with several other fast-industrializing Asian countries (Hauge Reference Hauge2023; UNIDO 2024).

Figure 1 World manufactured exports 2005–2023

A report by the World Bank (2021) argues that African countries currently enjoy favourable conditions to participate through manufacturing global value chains (GVCs), potentially giving them a window to industrialize faster. Hauge (Reference Hauge2023) corroborates this with evidence of a growing number of countries entering manufacturing GVCs despite pressures for reshoring, mostly in Asia but also gradually in Africa. Thus, the fact that China is expected to increase its share of global manufacturing output (UNIDO 2024) does not preclude the possibility of African countries expanding their industrial output, especially in sectors deemed obsolete or no longer viable in Asian countries – China included – which are rapidly upgrading to high-tech manufacturing exports. Moreover, African countries, especially those with large markets, can potentially expand their industrial production through import substitution, a strategy many other economies have pursued in the past and are still trying now.

Any structural transformation strategy can and should learn from past successes and failures (Oqubay Reference Oqubay, Oqubay, Cramer, Chang and Kozul-Wright2020). Historically, three stylized categories of industrializers can be identified. First, the experience of early industrializers such as Britain, which involved at least three interacting dominant factors (Allen Reference Allen2011): (a) the availability of a new form of cheap energy (coal) making energy-intensive production units viable; (b) processes of social change driven by enclosures driving the formation of a proletariat available to work in new factories at subsistence wages; and (c) the availability of cheap raw materials, primarily cotton for the textile industry, facilitated by British imperialism and slavery in the cotton-growing American South (Inikori Reference Inikori2020).

Second, the experience of late industrializers in Asia in the post–World War II period, where another recipe with distinct ingredients arose: (a) the rise of a developmental state, driven by the imperatives of regime survival in the context of the Cold War; (b) the absence of a powerful landlord class, which allowed emerging developmental states to drive the industrial transformation process through state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and the promotion of an incipient industrial bourgeoisie; (c) the external support provided by the US government in its fight against communism, opening policy space for countries such as Japan, Korea and Taiwan to experiment with combined import substitution industrialization (ISI) and export-oriented industrialization (EOI) in different sequences (Amsden Reference Amsden2001; Whittaker et al. 2020);Footnote 3 (d) the role of carefully managed FDI in bringing technology transfer and capital; and (e) a relatively educated, trainable workforce, which contributed to the rise of labour-intensive manufacturing, especially when labour disciplining and repression was exercised.

Third is the case of ‘compressed development’ industrializers (Whittaker et al. 2020), of which China is a leading example, involving: (a) the global rise of an organizational and technological network paradigm, which in turn facilitated the fragmentation, interconnections and complex organization of global production networks (GPNs); (b) global production fragmentation, with high-value activities located in HICs and transnational corporation HQs (R&D, design, innovation, branding, retail), and manufacturing assembly outsourced en masse to LMICs; and (c) technological change and innovation in logistics, alongside declining international trade costs, which together facilitated the dynamic of flexible specialization and trading in tasks (Page Reference Page2012), resulting in more widespread ‘thin industrialization’ (e.g. low-end basic assembly operations such as cut-make-trim in the apparel industry).

In all these structural transformation experiences, innovation, technological catching up, learning and emulation have been key, driving a transition from ‘easy’ light low-technology manufacturing to machine production and innovation-led industrial upgrading (Amsden Reference Amsden2001; Chang and Andreoni Reference Chang and Andreoni2021). Successful industrializers have upgraded to higher productivity and more technologically intensive manufacturing using learning rents, often supported by developmental states, to help build production and organizational capabilities at both the individual and collective level (Chang and Andreoni Reference Chang and Andreoni2021; Khan Reference Khan2019). China is perhaps the most striking example of a rapid transition from mass labour-intensive industrialization – predicated on low labour costs, combined with a skilled workforce and expanding infrastructure – to an innovation-centred industrial model that has put the country at the frontier of new technologies such as robotics, AI, and green products like electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries (Atkinson Reference Atkinson2024).Footnote 4

There is a consensus that Africa is the least industrialized region in the world, and that most of its countries are still in their infancy when it comes to manufacturing capabilities. However, this consensus masks significant variation across countries and over time periods. Postcolonial industrialization experience in Africa occurred in three main phases (Chitonge and Lawrence Reference Chitonge, Lawrence, Oqubay, Cramer, Chang and Kozul-Wright2020; Whitfield and Zalk Reference Whitfield, Zalk, Oqubay, Cramer, Chang and Kozul-Wright2020): first, an initial post-independence ‘art of the possible’, when several African governments used the state and state-created companies to pursue a broad-based industrialization agenda, mostly built on an ISI approach; second, the post-crisis liberalization and structural adjustment phase (1980–2010), when industrial policy was largely abandoned (with the notable exception of Mauritius) and trade liberalization and SAPs dominated the policy landscape, negatively affecting the limited industrial base of most countries; and third, an emerging revival on the back of some African leaders showing a willingness to emulate Asia’s industrialization success, partly driven by participation in GVCs/GPNs as offshoring extends beyond Asia.

This inconsistent trajectory has led to two contrasting narratives: one that emphasizes ‘premature deindustrialization’ (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2016), and another that suggests many African countries have suffered from ‘premature industrialization’, especially in the early post-independence phase (Robertson Reference Robertson2022). Although there is some evidence to support both arguments, it is mainly limited to specific country examples rather than applying continent-wide. Some countries did suffer from deindustrialization dynamics at the height of SAPs and trade liberalization in the 1980s and 1990s (Page Reference Page2012). Many countries that had started to industrialize, however, did not seem to have met the basic conditions proposed by Robertson (Reference Robertson2022) for industrial take-off in their initial phases, namely high adult literacy rates (70 per cent or more); high energy production and consumption per capita (over 300 kWh); and lower fertility rates. Even so, some countries – notably Ethiopia and Ghana – have recently managed to speed up manufacturing growth despite failing to fulfil these criteria (Balchin et al. Reference Balchin, Booth and te Velde2019). This conundrum also points to the debate on whether countries should follow or defy comparative advantage, and the resultant implications for whether African industrialization strategies should be bolder or more cautious (Lin and Chang Reference Lin and Chang2009; Lin Reference Lin2018; Chang and Hauge Reference Chang, Hauge, Cheru, Cramer and Oqubay2019).

Whether Africa has experienced ‘premature’ industrialization or deindustrialization largely depends on how one interprets these historical trajectories and ‘moments’ of capitalist development (Page Reference Page2012; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2016, Lee Reference Lee2017; Ggombe and Newfarmer 2018, Cramer et al. Reference Cramer, Sender and Oqubay2020; Robertson Reference Robertson2022). Thus, the recent ‘renaissance’ of industrial growth reflects patterns contingent on specific configurations of global, national and local forces, encompassing government policies and investment opportunities seized on by domestic, diaspora and foreign industrial capitalists. This ‘contingent’ industrialization includes both export-oriented ventures (e.g. Ethiopian, Ghanaian, Mauritian and Malgache industrial parks), and inward-looking ISI-like industrialization processes driven by domestic market dynamics, particularly linkages between construction and industrial development, as in Nigeria, Ethiopia and Angola (Itaman and Wolf Reference Itaman and Wolf2021; Wolf Reference Wolf2024). These are real industrial growth episodes, despite an aggregate decline in African manufacturing sector’s GDP share that has been driven by the effects of the commodity price boom and South Africa’s sluggish manufacturing performance.

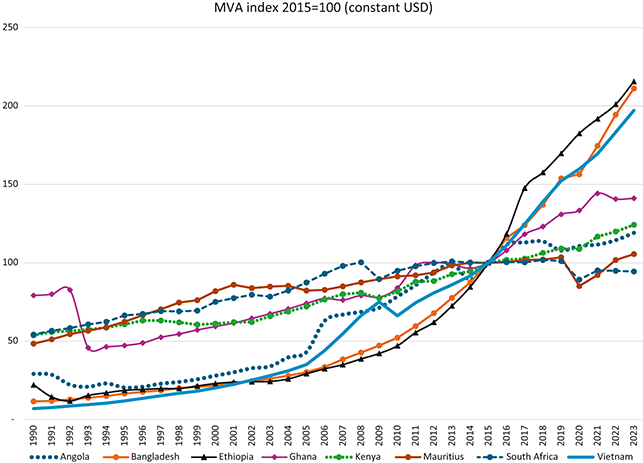

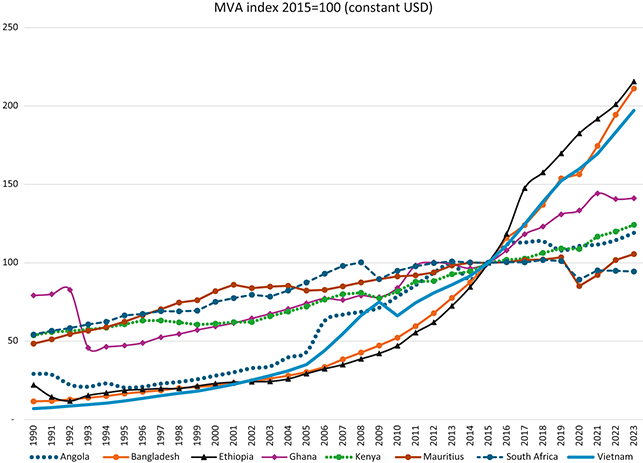

Overall, the main story of African manufacturing growth since 2000, when China’s engagement in the continent accelerated, is one of dramatic variation. While some countries have – admittedly from a very low base – grown rapidly and steadily since 2000, others have stagnated or even slightly regressed. Ethiopia is the leading example of the former, and South Africa an example of the latter. The unevenness of these processes is illustrated by Figure 2, which shows how Ethiopia has since 2000 almost mimicked in relative terms the incredible industrial growth experienced by Bangladesh and Vietnam since 1990, whereas growth in South Africa – Africa’s industrial powerhouse – has been remarkably sluggish over the past twenty years.

Figure 2 Manufacturing growth in selected economies (1990–2023)

1.2 The Argument

The main thesis of this Element is that a number of opportunities for economic transformation have been generated by the rapid expansion of ties between China and many African countries, reviving the prospects for industrialization and associated job creation in some of these countries. The economic transformations affecting China’s economic trajectory over the last two decades, especially the saturation of its low-technology labour-intensive manufacturing, and overcapacity in construction activities, underpin some of these opportunities (Lin and Xu Reference Lin, Xu, Oqubay and Lin2019; Tang Reference Tang2020). However, outcomes vary considerably across Africa, and these are still early days for recent industrialization processes. While structural and policy obstacles mean few countries have fully exploited these opportunities yet, the relative strength and vision of national institutions, particularly the state’s ability to discipline (foreign and domestic) capital, appear to be critical determinants of the success, failure or sustainability of current economic transformation experiences fuelled by Chinese official finance and state or private capital.

Furthermore, multiple barriers and contradictions stand in the way of building an industrial workforce in countries that lack industrialization experience. As such, despite industrialization offering the promise of large numbers of decent jobs, progress is likely to be slower and more uneven than expected. The kinds of investment and employment dynamics associated with Chinese-driven FDI and infrastructure development are therefore very different between, say, Angola and Ethiopia, where Chinese engagement since the early 2000s has been particularly intense. Even within Ethiopia, the fragile political settlement has put the current industrialization model’s viability in doubt, regardless of China’s engagement. In sum, there is enough evidence to suggest the last two decades of engagement of China in Africa have helped lay the foundations for industrialization efforts in those countries attempting to make them. However, the impact would be much greater if African elites and their governments were more committed to and embraced the idea of ‘modernizing structural change’, exploring with an open mind the lessons from China’s structural transformation (Opalo Reference Opalo2024).

This Element is not just about China’s engagements in Africa. It is also about Africa’s legitimate right to development and structural transformation, and the realities and prospects arising from this. As such, this Element is not just about Chinese finance and firms in Africa, but also their African workers, and how China’s engagements remind us of the often contradictory, complicated, and contested process of building an industrial workforce. It is not just about drivers of Chinese engagement in Africa and their contributions to industrialization, but about how African agency shapes variations in experiences, and how the interplay between politics and economic forces is key to explaining such variation. In sum, it is as much or more about African countries (e.g. Ethiopia, Angola, Nigeria) as it is about ‘Global China’.

Building on the aforementioned, this Element rejects methodological nationalism, ‘which has artificially sealed Chinese phenomena within China’s geographical borders’ (Lee Reference Lee2017, 166). By contrast, fine-grained, grounded empirical and comparative research helps transcend the trap of ‘grandiose generalization in terms of hegemony, empire, and neocolonialism’ (Lee Reference Lee2017, 161).

The Element is based on two main sources of evidence. First, it draws on the excellent fieldwork-based scholarship exploring the extent to which China’s engagement in Africa promotes industrialization, and the variegated development dynamics this has brought about (Sun Reference Sun2017; Brautigam et al. Reference Brautigam, Tang and Xia2018; Oqubay and Lin Reference Oqubay and Lin2019; Chen Reference Chen2021; Calabrese and Tang Reference Calabrese and Tang2023; Tang Reference Tang2023; Zhou Reference Zhou2023; Mamo Reference Mamo2024; ), along with a large set of secondary sources (data and literature).Footnote 5 Second, it employs primary comparative evidence collected by the IDCEA project (Industrial Development Construction and Employment in Africa) on employment dynamics in manufacturing and infrastructure construction, conducted over three years of fieldwork (2016–2019) in Angola and Ethiopia.Footnote 6 The latter research includes one of the largest quantitative surveys yet conducted of African workers employed by Chinese and other firms in these two sectors, garnering responses from over 1,500 workers in almost 80 firms, of which 31 were Chinese (Oya and Schaefer Reference Oya and Schaefer2019). The project also conducted over 270 qualitative interviews with company managers, government officials, workers (several life-employment histories), international agencies, industry experts, and other key informants in different phases.

The implications of this analysis for broader debates on development in Africa are significant. At a time when post-development and new decolonial narratives abound, it is important to recentre Africa’s plight in the challenges, opportunities, and contradictions of real development. This includes taking account of the legitimate aspirations held by most Africans to achieve structural change, material improvements, and socio-economic progress, while not ignoring the violence and tensions in the processes of capitalist transformations. The term ‘modernization’ is often used in ‘Global China’ discourses, and has increasingly been appropriated by African elites and intellectuals. Ordinary Africans deserve better roads, transport connectivity, access to electricity, health facilities, more and better jobs – precisely the outcomes we associate with ‘development’. The quest for African ‘modernity’ is no longer simply a colonial project, but reflects the desires of millions of ordinary Africans and their elites (Mkandawire Reference Mkandawire and Mkandawire2005; Opalo Reference Opalo2024). Opalo and Taiwo, two renowned African intellectuals, have echoed the words of the late Mkandawire (Reference Mkandawire and Mkandawire2005, 14) in issuing a call to embrace ‘African modernity’, arguing that, despite some imposed undesirable ‘development models’, ‘the objective of development in the broad sense of structural change, equity and growth [is] popular and internally anchored’.

2 China’s Engagements in Africa Supporting Industrial Development

2.1 Framing ‘Global China’ Contributions to Africa’s Industrialization

Having established the desirability of structural transformation through industrialization in Africa, this section offers an overview of the extent to which China has contributed to emerging industrialization efforts since the early 2000s, and the main mechanisms used.

In particular, two major mechanisms are examined in this section. First, facilitation of a substantial expansion in economic infrastructure from a very weak base, especially the kinds of infrastructure most likely to enable manufacturing development – namely, energy, transport, and industrial parks. The funding and building of such infrastructure may be regarded as central contributions, and indeed the basic foundations, of industrial development. Thus, while the relevant infrastructure does not guarantee industrial development, it does constitute a necessary precondition. Second, in the absence of an experienced, developed indigenous industrial capitalist class, the arrival of manufacturing investors in the form of FDI plays a central role. FDI-driven industrialization has been a key characteristic of ‘compressed development’ era (Whittaker et al. 2020). The section summarizes and evaluates evidence at continental and country level (for selected country cases) about the volume and trends of official finance, infrastructure building, and FDI, with a particular focus on what is relevant for processes of industrialization.

Variation in outcomes also depends on the scale and nature of the ‘varieties of capital’ entering African countries. Three key types dominate the landscape of Africa–China encounters: (a) state finance capital (policy banks like Eximbank); (b) SOEs in construction services; and (c) private manufacturing firms. Here, the ‘varieties of capital’ concept allows for more fluid theorization, and encourages awareness of adaptations to different political, economic and social contexts (Lee Reference Lee2017). Compared to more seasoned Western firms, Chinese varieties of capital often lack overseas experience and may therefore be more vulnerable to unexpected shocks and events (Lee Reference Lee2017, 160). In addition, Chinese state capital may differ from global private capital in applying the logic of ‘encompassing accumulation’ rather than being solely driven by shareholder value maximization. Thus, some Chinese companies may be driven by pure profit maximizing while others combine profits and market expansion, with more complex combinations potentially occurring involving profit, political patronage, and influence (diplomacy), as well as access to commodities at source.

Overall, the increasing flows of Chinese development finance, construction services, and FDI over the past two decades have taken place in the context of China’s intertwined challenges of overaccumulation and overcapacity in certain productive sectors, and the governance and legitimacy of the country’s development model (Hung Reference Hung2008; Lee Reference Lee2022; Strange Reference Strange2023). These logics of accumulation and ‘going out’ are determined by the combined effects of ‘variety of capital’, sector, host country factors, and connections with other actors in China and host countries. In turn, their developmental impacts hinge on the extent of linkages with other sectors, technology transfer, spillovers to other domestic firms, generation (or saving) of foreign exchange, job creation, skill development, and the contribution to easing binding constraints on structural transformation.

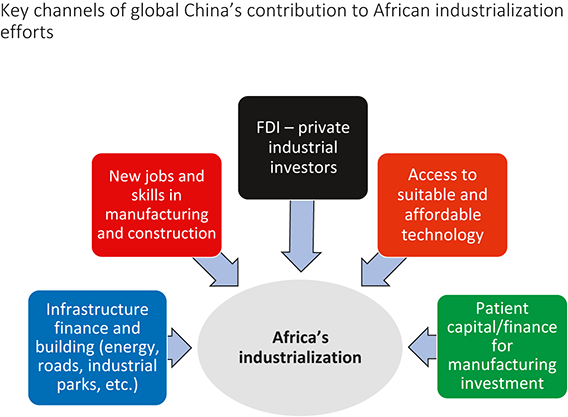

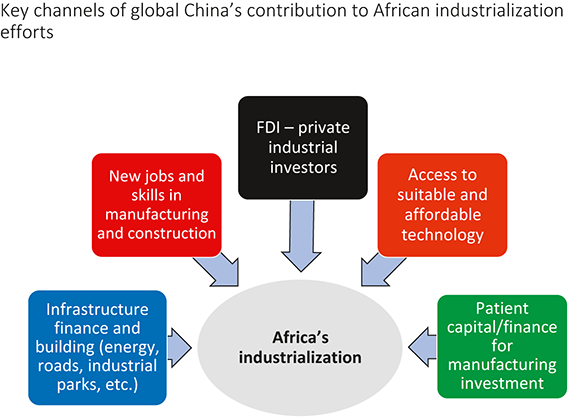

Combining these perspectives, it is possible to depict a set of essential vectors that can potentially (and actually) contribute to Africa’s industrialization efforts, as demonstrated by Figure 3. Two vectors dominate: first, the funding and building of key economic infrastructure conducive to industrial investment, notably energy, transport, and industrial hubs; and, second, direct investments in the manufacturing sector, typically by private firms – especially those that have GVC experience and contribute to Africa’s manufacturing exports – and represented by FDI flows.

Figure 3 Key channels of China’s contributions to Africa’s industrialization

These two vectors are intimately linked to three other important mechanisms. First, contractors and manufacturing investors create new jobs for local workers in manufacturing production or construction, providing not just livelihoods to thousands of Africans, but new skillsets that are often acquired on the job and over time provide an effective basis for industrial development. The transfer of organizational capabilities (as in factory management and work) is a long-standing enabler of sustained industrialization, evidenced by the work of Amsden and Hirschman. As Amsden (Reference Amsden2012) insists, the mass creation of jobs in viable enterprises and higher productivity sectors contributes to ‘manufacturing’ experience by creating an emerging industrial workforce with skills deployable across different sectors as other investment opportunities arise.

Second, manufacturing and construction investors often come with technology and capital equipment potentially suitable to the conditions of African markets. When this technology is affordable, there is potential for spillover effects onto domestically owned firms, which may contribute to industrial eco-systems clustered around specific sub-sectors, eventually inducing new activities and investments (Best Reference Best2018). The imported technology’s suitability and affordability is critical in this case, with the establishment of direct linkages between foreign investors and local suppliers a necessary step in the process (Tang Reference Tang2023). These are not automatic but can be incentivized by industrial policy interventions.

Third, industrial development in low-income country contexts is inherently risky – certainly more so than other activities that have tended to attract the attention of domestic capitalist classes, namely finance, trade and real estate (Goodfellow Reference Goodfellow2020). Thus, the availability of patient finance – not just for large economic infrastructure projects but for manufacturing investments, especially industrial hubs – may be crucial to unlocking profitable investments that might otherwise go unfunded, especially in contexts where capital markets perceive a high-risk business environment. Indeed, lack of access to finance is typically a major constraint for local African manufacturers and an impediment to further growth (McMillan and Zeufack Reference McMillan and Zeufack2022). As such, long-term finance on terms that are favourable to the development of industrial eco-systems is likely to contribute to more sustained industrialization, regardless of whether it is driven by FDI. When patient finance for local entrepreneurs is missing, FDI becomes one of the few realistic vehicles for industrial development and technological catching up.

The following two subsections unpack the dynamics of expansion of Chinese-funded and -built infrastructure and Chinese FDI into the manufacturing sector. For both phenomena the main implications for Africa’s industrialization are teased out, given the evidence to date.

2.2 Financing and Building Infrastructure for Structural Transformation

2.2.1 The Centrality of Economic Infrastructure in Structural Change

The past two decades have seen a construction drive across Africa, coinciding with the arrival of Chinese finance for infrastructure and Chinese construction companies, broadly reflecting a global expansion of China’s infrastructure industry (Goodfellow Reference Goodfellow2020; Strange Reference Strange2023; Gambino and Bagwandeen Reference Gambino, Bagwandeen, Hönke, Cezne and Yang2024, 205; Dappe and Lebrand Reference Dappe and Lebrand2024). Beyond infrastructure’s overall importance for economic development and legitimacy vis-à-vis society, there are three specific reasons why supporting the development of basic economic infrastructure is critical for industrial development in Africa and anywhere.

First, electricity matters. Any industrialization process is energy-hungry – ever since the first industrial revolution, the availability and use of cheap energy has been a foundational factor (Allen Reference Allen2011; Robertson Reference Robertson2022). Investments in power generation capable of providing lower electricity costs and a reliable power supply to factories are necessary conditions for establishing well-run, competitively costed factories, especially when competing in global markets. In our firm surveys, a key reason given by most foreign investors for setting up apparel factories in Ethiopia was cheap, reliable electricity, facilitated by substantial investments in hydropower generation. Here, both electricity production/consumption capacity and prices matter. Ethiopia and Angola now have electricity prices of about 3.6 US cents per kWh, among the cheapest in Africa and lower than Bangladesh and Egypt (both at 9.7 US cents). However, in terms of electricity consumption per capita, both Angola and Ethiopia remain well short of other late industrializers and Robertson’s thresholds of 300-500 kWh per capita. Even so, Ethiopia has seen a very significant increase over the past 10–15 years thanks to major investments in hydropower generation, which has in turn serviced a growing number of industrial parks. In Africa, only highly urbanized countries with some energy-intensive industries have reached very high levels of electricity consumption per capita (e.g. South Africa).

Second, countries aspiring to develop manufacturing through participation in GVCs need infrastructure that facilitates trade. Lower transportation and logistics costs are crucial not only for enhancing export competitiveness, but fostering more integrated domestic and regional supply chains (World Bank 2021). In an era when Africa’s regional trade is promoted through the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), regional connectivity is a must. Investments in expanding road networks, railways, ports and logistics infrastructure are fundamental to building robust industrial eco-systems, a principle that has guided industrial development both historically and today. Transport infrastructure is of course also instrumental to the expansion of home markets, which too are essential for sustained industrial transformation.

Third, East Asia’s experience of industrialization underscores the importance of dedicated industrial hubs that can help realize agglomeration economies, strengthen intra- and inter-sector linkages, and reduce the costs of accessing essential infrastructure – factors critical to sustained industrial growth (Oqubay and Lin Reference Oqubay and Lin2019; Oqubay Reference Oqubay2022). Moreover, industrial hubs play a key role in managing migrant workforces, facilitating adaptation to rapid social and labour market changes, and helping build an industrial workforce (Oya and Schaefer Reference Oya, Schaefer, Oqubay and Lin2020; Gebrechristos Reference Gebrechristos2025).

The aforementioned infrastructure areas are, in fact, the three that China has placed most emphasis on in its own quest for accelerated industrialization (Brautigam Reference Brautigam, Oqubay and Lin2019). Chinese engagement in Africa’s infrastructure finance since 2005 has been considerable, whether through provision of patient finance for basic economic infrastructure or direct involvement in strategic infrastructure projects. This is important because, when combined, deficits in these three key infrastructure areas hinder structural transformation and future growth. The challenge, however, is that consistent investments in the three areas are needed over long periods of time. Overall, the African Development Bank (ADB) estimates that ‘poor infrastructure shaves up to 2 per cent off Africa’s average per capita growth rates’ (ADB 2018, 73).

2.2.2 Chinese Development Finance in Africa

How has China contributed to Africa’s recent infrastructure drive? One leading mechanism is dedicated infrastructure finance, mostly concentrated in the first two of the aforementioned three areas. While industrial hubs (or special economic zones, SEZs) have also received some backing, these have received lower Chinese official funding volumes and attracted a wider range of players, including private companies and provincial government agencies, as in the Eastern Industrial Zone (EIZ) of Ethiopia, one of the two largest industrial hubs in Africa (Brautigam Reference Brautigam, Oqubay and Lin2019; Oqubay Reference Oqubay2022; Chen Reference Chen2024).

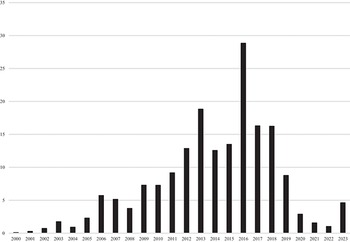

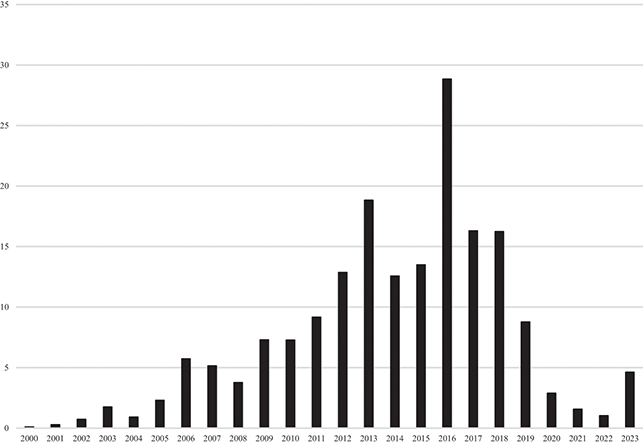

Figure 4 indicates the overall trend between 2000 and 2023. During the period 2011–2019, Chinese loans from policy banks – mostly going to infrastructure – hovered around the $10bn–15bn mark annually, two-thirds of which went to power and transport alone. This compares with a total annual infrastructure finance average of $77bn in 2012–2017, of which $20bn came mostly from OECD countries, making China the single largest financing source, bilateral or multilateral (Gu and Carney Reference Gu, Carey, Oqubay and Lin2019, 154; ICA 2018). This volume of Chinese funding is also relevant to the estimated infrastructure gap of between $70bn and $108bn per year, as estimated in 2015 and 2018 (Dethier Reference Dethier, Monga and Lin2015; African Development Bank 2018). This is not a negligible proportion, considering there are multiple lenders operating in the continent, with the World Bank as the leading development finance source in most African countries.

Figure 4 Chinese loans to Africa (US$ bn)

Recent trends in Chinese development finance point to shifts in mood and modalities. Although the volume of policy bank development finance for infrastructure seemed to dry up in 2020–2022, it rebounded to some extent in 2023 (Figure 4; Engel et al. Reference Engel, Hwang, Morro and Bien-Aime2024), directed at several familiar suspects among borrowers (Angola, Egypt, Nigeria) and project types (power generation, transport). At the same time, it revealed some inclination towards smaller, leaner, ‘greener’ infrastructure projects. Meanwhile, and especially since 2015, state-owned commercial banks increased their share of financing, up to 40 per cent of total lending to Africa in the most recent estimates (Wu and Chen 2024). This diversification in credit sources reduces the risks faced by Chinese financial institutions, especially the exposure of policy banks such as Eximbank, but makes some of the new debt more commercially oriented and therefore similar to what African governments get from Western commercial creditors. The main difference in 2023 was a significant Chinese commitment towards the financial sector, notably African multilateral banks (Afreximbank, Africa Finance Corporation) and some national banks, with a portion of this funding potentially dedicated to infrastructure. This new trend perhaps signals ‘a risk mitigation strategy that avoids exposure to African countries’ debt challenges’ (Engel et al. Reference Engel, Hwang, Morro and Bien-Aime2024, 2).

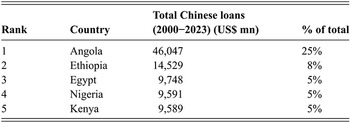

The top five recipients of official loans accounted for practically 50 per cent of China’s whole policy bank loan portfolio to Africa during the period 2000–2023, with Ethiopia and Angola alone accounting for a third of loans (Table 1). Although most African countries received some official finance during this period, the concentration of loans is significant. This is despite the figure for Angola skewing the results, especially given the massive refinancing package the country received in 2016, which did not bring fresh finance and included recapitalization of the leading national oil company Sonangol (Acker et al. Reference Acker, Brautigam and Huang2020). More generally, the concentration of infrastructure finance is a driving factor behind the variation of outcomes in China’s contribution to industrialization across the continent.

| Rank | Country | Total Chinese loans (2000−2023) (US$ mn) | % of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Angola | 46,047 | 25% |

| 2 | Ethiopia | 14,529 | 8% |

| 3 | Egypt | 9,748 | 5% |

| 4 | Nigeria | 9,591 | 5% |

| 5 | Kenya | 9,589 | 5% |

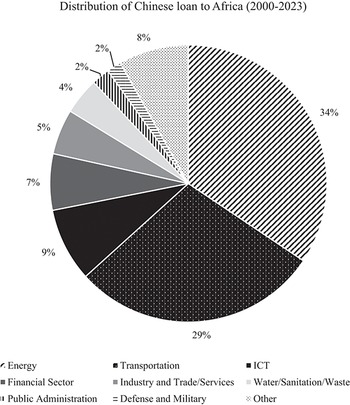

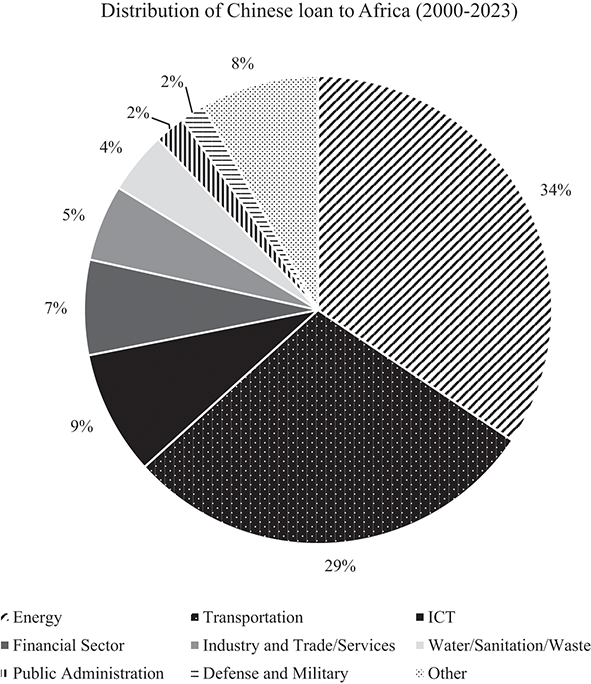

There are two distinct advantages to the development finance provided by Chinese state institutions, especially policy banks. First, they overwhelmingly focus on much-needed hard economic infrastructure (roads, ports, power generation) and productive sectors, which is particularly critical following decades of underinvestment in these areas (Figure 5; Brautigam Reference Brautigam, Oqubay and Lin2019).Footnote 7 By contrast, the World Bank – the key development bank for Africa – currently devotes only about 30 per cent to infrastructure, including about 25 per cent for transport, energy and mining combined, which is well below the figures for Chinese finance.Footnote 8 In the SAPs era of the 1980s and 1990s, the share was even lower.

Figure 5 Distribution of Chinese loans to Africa by sector by % (2000–2023)

Given the World Bank’s core remit, at least until the 1970s, has been to finance hard infrastructure, this appears paradoxical. Over the past three decades, African countries have persistently made use of World Bank funding, but deindustrialization or reverse structural change has nevertheless occurred in many of them (McMillan et al. Reference McMillan, Rodrik and Verduzco-Gallo2014), especially in the 1980s and 1990s. Why? In answering this question, it is important to focus on the sector allocation of loans and associated donor imperatives in Africa during this period. For too long, this development finance has been reoriented towards priorities aligned with the new ‘consensus’, whether liberalization, structural adjustment reforms or the ‘good governance’ agenda – in short, policy reforms. By contrast, the funding of basic economic infrastructure did not feature prominently in such imperatives. When Chinese funding started to grow to substantial levels around 2010, the economic infrastructure situation facing African LICs was abysmal. Not only were road/railroad density and relative electricity-generating capacity much lower than in other developing regions (respectively, a third and 40 per cent of South Asia’s levels), but these indicators either worsened or barely improved between 1990 and 2012 (Calderon et al. Reference Calderon, Cantu and Chuhan-Pole2018). This a serious indictment of the paltry efforts African governments and their main infrastructure finance backers (notably the World Bank and the European Union) made before Chinese lenders emerged.

A second advantage of Chinese development finance in Africa (and the Americas for that matter) is its inclination to act as ‘patient capital’, especially when policy banks are the source (Eximbank and CDB – China Development Bank). Kaplan (2021) argues that China’s overseas development finance is a distinct form of patient capital involving long-term risk tolerance (hence ‘patient’) and absence of policy conditionality, contrary to the traditional practice of Western lenders. This is particularly the case for policy banks such as Eximbank, which follow the logic of ‘building ahead of time’, rather than the more narrow-minded, cost-benefit approach favoured by traditional financiers, who base their lending on shorter-term estimated rates of return, when demand for infrastructure is already latent (Lin and Wang Reference Lin and Wang2017; Gu and Carney Reference Gu, Carey, Oqubay and Lin2019). This also reflects a public investment-led approach, in contrast to the tendency of other development banks to promote private sector solutions (Gu and Carney Reference Gu, Carey, Oqubay and Lin2019, 158). An important advantage of ‘buying ahead of time’ is that infrastructure is built when construction costs are lower compared to when the need becomes urgent (Lin and Wang Reference Lin and Wang2017). As Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1967) argued in Development Projects Observed, the long-term (positive) unintended effects of large, risky infrastructure projects (principle of the ‘hiding hand’) are essential for learning when it comes to economic transformation processes. Such projects, however, require long-term commitments on favourable terms. This has largely been the case for Chinese finance, which often comes from institutions such as Eximbank or CDB. Although not always concessional, there has consistently been long negotiable maturity and significant debt relief, flexible debt management, and adjustments in loan conditions (Acker et al. Reference Acker, Brautigam and Huang2020).

The rapid, large increases in finance towards long-term maturity infrastructure projects in high-risk African countries (Angola, Nigeria, Ethiopia) attests to the degree of ‘patience’ in Chinese development finance. Unconventional approaches to risk management have also helped, as the ‘Angola model’ shows, whereby Eximbank negotiated further security by linking its loan to future oil stream income that would involve a Chinese oil firm importing the fuel (Brautigam Reference Brautigam, Oqubay and Lin2019; Large Reference Large2021).Footnote 9 This meant Eximbank was able to extend large credit lines with relatively limited risk, as disbursements would be linked to repayments in a China-based escrow account.

Finally, the degree of ‘patience’ in development finance facilitates a drive to leapfrog technology and business model changes, particularly in the case of digital technologies, where both Chinese lending institutions and major ICT firms like Huawei have established an important footprint in many African countries (Gu and Carney Reference Gu, Carey, Oqubay and Lin2019). These higher-risk ventures can potentially accelerate structural transformation in the coming decades if such commitments are sustained.

Of course, patience is not limitless, and not all Chinese banks offer the same terms and conditions. Some are more commercially and short-term oriented, and less focused on the green infrastructures of the future (Wu Reference Wu2024; Wu and Chen 2024). Recent trends suggest Chinese development finance institutions are running out of patience and since 2019 have become more risk averse, especially given evidence of debt distress and repayment difficulties among some high African borrowers (Angola, Zambia, Ethiopia), indicating that some rebalancing in Chinese loan commitments is needed (Wu and Chen 2024). Responses have ranged from debt relief or cancellation to rebalancing towards smaller, less risky projects (Acker et al. Reference Acker, Brautigam and Huang2020; Wu Reference Wu2024). The decline in funding volume since 2018 represents a worrying trend, as the need for patient capital to fill Africa’s infrastructure gap is far from over. On the contrary, as more African countries seek to industrialize, infrastructure needs are only likely to grow faster. Sustaining ‘patient capital’ flows therefore remains a priority, even taking into consideration debt stress situations. The trade-off between potential debt distress and lack of sufficient long-term finance is real, and needs addressing through a coherent, carefully managed structural transformation plan.Footnote 10

Overall, despite the recent decline in Chinese loans, the rapid growth in infrastructure finance and Chinese infrastructure contractors (more next) may have laid the foundations for further structural transformation in a number of countries. It has certainly contributed to reversing the trend of ever-growing infrastructure funding gaps in Africa. As the next subsection will document, aside from the broader role of infrastructure in structural change, the flood of new projects and contractors also creates demand for local construction material manufacturing, inducing further investments in these sectors. In this respect, the strong direct and indirect linkages between basic economic infrastructure and industrial development are well established.

2.2.3 Chinese Contractors and Infrastructure Development

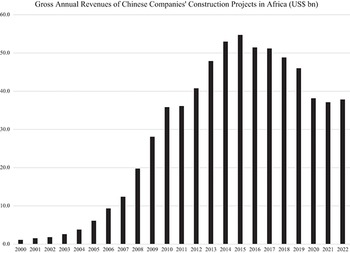

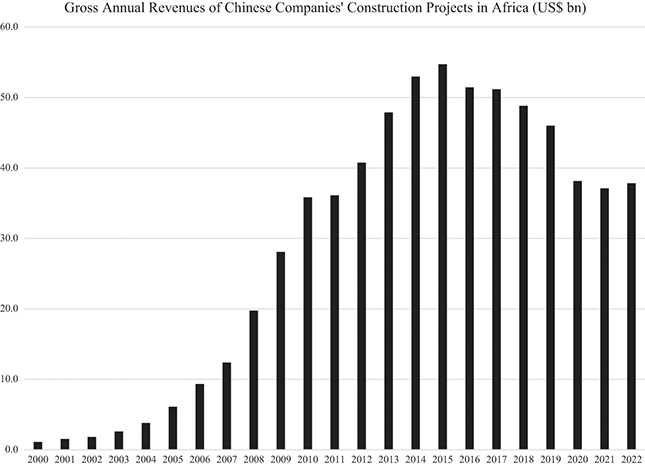

The second key mechanism supporting African economic infrastructure is the direct participation of Chinese contractors in infrastructure design and building, usually through engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) projects. This is perhaps even more remarkable than the increase in loans. Figure 6 shows a surge in the gross annual revenues of Chinese companies’ construction projects in Africa from less than $2bn before 2003 to a peak of over $50bn in 2015, with a slowing down thereafter. This dramatic rise closely followed patterns in Chinese official finance, though the ratio of Chinese finance to contractor revenues ranges from 40 per cent in the Democratic Republic of Congo to less than 20 per cent in half the sample of African countries, suggesting a greater reliance on other sources of finance (Zhang Reference Zhang2021, 7). As a result of this rapid expansion, Chinese contractors accounted for over 60 per cent of Africa’s construction and infrastructure market by 2019, up from only 10 per cent in 2003 (Zhang Reference Zhang2021). In Ethiopia, Chinese companies participated in about 60 per cent of all road works between 2000 and 2019. For both road and railway projects, most of the funding actually came from the Ethiopian government through their multiple partners (African Development Bank, World Bank and Arab development finance institutions) (Cheru and Oqubay Reference Cheru, Oqubay, Oqubay and Lin2019, 294).The Africa market also substantially grew in importance as a share of Chinese construction companies’ gross annual revenues, from 13 per cent in 2001 to a peak of 37 per cent in 2014 (based on data from China Statistical Yearbook).

Figure 6 Gross annual revenues of Chinese companies’ construction projects in Africa (US$ bn)

The main reason for this success is that, despite obvious finance-tying (Chinese firms being the sole eligible contractors for Chinese-funded projects), these firms are highly competitive when it comes to both technical and financial specifications (Zhao and Shen Reference Zhao and Shen2008; Zhang Reference Zhang2021), with their vast experience in China’s infrastructure market compensating for lack of overseas experience (Zhou 2022). In the very segmented Angolan market, some Chinese contractors operated at lower margins to expand their market shares (Wanda et al. Reference Wanda, Oya and Monreal2023) and not at the expense of quality, as a recent comprehensive study has demonstrated (Kenny et al. Reference Kenny, Duan and Gehan2025).

Most Chinese contractors are SOEs, from both central and provincial levels, and operate on EPC terms. This means they often organize the subcontracting schemes in the projects they execute under the agreed arrangements with the local client (usually an African government), and can accommodate tight margins. These firms constitute a particular variety of Chinese state capital distinct from other forms of state capital engaged in mining, in the sense that ‘instead of resource scarcity, the impetus for the construction sector to go global was overcapacity’, driven by China’s own incentive systems to promote and subsidize growth at local and macro levels (Lee Reference Lee2017, 24). Thus, overcapacity in China and infrastructure deficits in African countries have made for a powerful combination.

Not all infrastructure built by Chinese contractors has directly contributed to the ‘economic hardware’ that industrialization requires. The logic of ‘encompassing accumulation’ means these players have also sought to accommodate whatever their African counterparts have requested, whether for political, ideological, electoral, or legitimacy reasons, including symbolic projects (public buildings, stadiums), real estate development linked to local elites, and transport connections of dubious value (Soares de Oliveira Reference Soares De Oliveira2015; Taylor Reference Taylor, Oqubay and Lin2019). After all, the model does not require Chinese funders and contractors to dictate the choice of infrastructure. Despite these ‘distractions’ from the bottom line, the fact remains that key power and transport projects have dominated the Chinese building landscape in Africa.

Indeed, it is undeniable that both development finance and Chinese contractors have made substantial contributions to the kind of infrastructure that facilitates industrial investment. For example, Ethiopia’s installed electricity generation capacity increased from 814 MW to over 4,200 MW between 2005 and 2021, while in Ghana it more than doubled to reach a capacity of 5,449 MW.Footnote 11 In Ethiopia, all this expansion was through renewables, mainly hydropower. During the same period, both countries became net exporters of electricity. Chinese lenders, contractors, and input suppliers were involved in nearly all of Ethiopia’s power generation projects (Cheru and Oqubay Reference Cheru, Oqubay, Oqubay and Lin2019, 294).

It is hard to find an accurate time series for direct contributions to basic economic infrastructure by Chinese actors. Instead, the most relevant figures are provided by a report from China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), which gives an aggregate estimate for an unspecified time period, linked to the Belt and Road Initiative. More specifically, the report estimates that, until 2022, ‘Chinese companies have participated in building and upgrading more than 10,000 kilometres of railways, nearly 100,000 km of highways, nearly 1,000 bridges and 100 ports, and 66,000 km of power transmission and distribution lines in African countries. They have also helped build a backbone communications network of 150,000 km in Africa’.Footnote 12 Another source refers to more than 80 large-scale power stations, more than 130 medical facilities, and dozens of sports venues and schools.Footnote 13 These impressive results are nonetheless unevenly spread, as contractor revenues, like development finance, remain highly concentrated in a group of countries including Angola, Algeria, Nigeria, and Ethiopia, with around 40 per cent of the accumulated total in 2000–2022 (estimates calculated from data extracted from www.sais-cari.org/data-chinese-contracts-in-africa).

The establishment of industrial parks, funding for which has been much more diversified (i.e. not dependent on classic loans from policy banks), are a highlight of the linkages between infrastructure development and the building of industrial capabilities. Latest estimates suggest that 25 Chinese-funded parks have been built and entered operation in Africa as of 2023, attracting more than 620 enterprises with cumulative investments of $7.35bn, especially towards domestic market sub-sectors (CABC 2024, 29).

There are four main reasons why the rise of Chinese contractors may be good news for Africa’s industrialization aspirations. First, their capacity to swiftly execute complex infrastructure projects at relatively low cost facilitates the expansion of critical infrastructure necessary to accelerate industrialization investments. In most cases, the contractors follow an EPC approach, whereby they are directly funded by the creditor agency, bypassing potential capacity constraints on the client side (say, the national road authority) and so speeding up project completion (Gu and Carney Reference Gu, Carey, Oqubay and Lin2019, 157).

Second, as will be discussed in Section 3, these projects create numerous jobs for African workers, despite dubious claims that most workers are Chinese. Beneficiaries of infrastructure-related jobs are often low-skilled workers from rural origins, meaning they may have the opportunity to gain transferable skills that can be applied to factory settings, as the connections between infrastructure construction and factory work in Angola suggested.

Third, insofar as economic infrastructure contributes to the development of industrial sector export capabilities by reducing the costs associated with connectivity and logistics, infrastructure improvements may ease foreign exchange constraints. There is, however, no reliable evidence on the net effect. Here, one key example is the construction of SEZs and industrial parks, which may lead to reduced foreign exchange constraints either through manufactured export promotion or import substitution, which reduces forex leakages.

Fourth, there is growing evidence that infrastructure contractors generate an ‘induced demand’ effect arising from building material imports linked to large-scale infrastructure development (Wolf Reference Wolf2024). Angola and Ethiopia are good examples, even if the scale of these linkages differs between the two countries. The sequence is as follows. A rapid infrastructure drive necessitates large quantities of building materials, especially cement and steel. In Angola, during the early days of the post-war boom, most of these materials were imported, thereby contributing to forex leakages. The rapidly expanding market stoked the interest of local and foreign investors, who sought to invest in processing facilities capable of producing cement, steel, and their associated inputs, as well as other building materials. Thus, a manufacturing sector emerged in response to these developments. In short, the demand-inducing effect of rapid infrastructure construction led to the growth of a typically domestic market-oriented manufacturing activity, an effect anticipated by Hirschman’s work and highlighted by Wanda et al. (Reference Wanda, Oya and Monreal2023) and Wolf (Reference Wolf2024) in the case of Angola. In fact, it represents a classic example of effective ISI, supported by governmental trade protection measures. Wolf (Reference Wolf2017 and Reference Wolf2024) has documented this sequence using the examples of Angola, Ghana, and Nigeria, where infrastructure construction became a ‘springboard for industrialization’, resulting in a variegated pool of small, medium, and large manufacturing enterprises producing high-demand building materials.

On balance, a majority of studies reviewed for this Element and our own primary research suggest that Chinese-funded and -built infrastructure projects – especially in power generation, transport (trade facilitation) and industrial parks – have contributed to more greenfield investments in manufacturing production, or at the very least created favourable conditions for these to happen in future (Darko and Xu Reference Darko and Xu2024; Qobo and Le Pere 2017; Lu and Liu Reference Lu and Liu2018; Alden and Lu Reference Alden and Lu2019; Brautigam Reference Brautigam, Oqubay and Lin2019; Megbowon et al. Reference Megbowon, Mlambo and Adekunle2019; Li and Lu Reference Li and Lu2024) Wolf Reference Wolf2024). A key role in this regard is reducing risk for future investors, thereby laying the foundations for private capital to find profitable opportunities in manufacturing, and becoming effective ‘brokers’ for first movers so that industrial ‘flying geese’ can follow (Lin and Xu Reference Lin, Xu, Oqubay and Lin2019, 279). Of course, infrastructure must be targeted to facilitate such investments, with – as will be argued in both the remainder of this section and in Section 4 – a conducive, bold industrial policy framework needed to support this on a sustained basis.

2.3 Chinese Foreign Direct Investment: Varieties of Capital in Manufacturing

2.3.1 Chinese FDI Trends in Africa

As argued in Section 1, several industrialization stories feature foreign capital as a driving force. FDI-led industrialization has also become more common in the era of ‘compressed development’ (Whittaker et al. 2020), with an increasing number of countries attempting to industrialize through participating in expanded GVCs/GPNs. FDI to Africa has historically been dominated by investments in the resource extractive sectors, sometimes including mineral processing, where linkages and spillovers into local firms are limited (Morrissey Reference Morrissey2012). Much of the limited recorded manufacturing FDI from Western sources has been directed at mineral processing in countries such as South Africa or Botswana (diamonds); some basic oil processing in oil-producing countries; or large aluminium smelters, as in Mozambique since 1999. FDI to services, especially banking, construction, and ICTs, also expanded after the waves of liberalization seen across the continent in the 1990s (Morrissey Reference Morrissey2012).Footnote 14 McMillan (2017) notes the growing diversification of FDI sources into Africa, driven by Chinese investments, which has also led to sector diversification away from mining and resource extraction in general. This suggests that Chinese FDI may be different from its Western equivalents, especially in those countries where the focus is on non-resource related manufacturing.

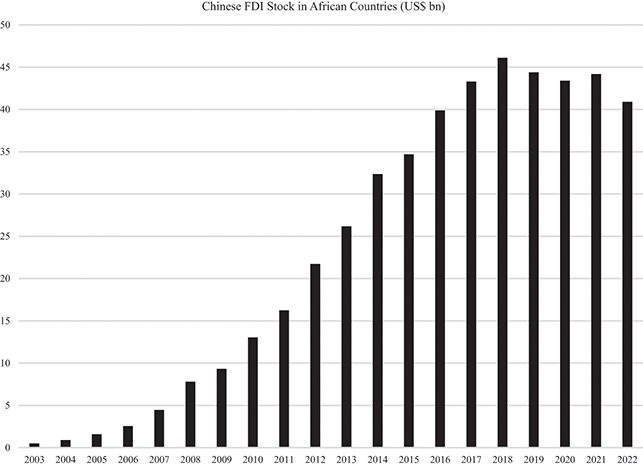

It is important to note that official data of Chinese FDI as published by MOFCOM and UNCTAD are known to underestimate true figures, as large numbers of Chinese-owned enterprises (including greenfield investments in most cases) are not registered through MOFCOM channels, particularly for lower investment volumes, therefore especially affecting estimates of Chinese FDI into manufacturing and services (McKinsey 2017; Sun Reference Sun2017; Brautigam et al. Reference Brautigam, Diao, McMillan and Silver2019; Chen Reference Chen2024). The aggregate official numbers for Chinese FDI in African countries presented in Figure 7 reveal a mixed picture, characterized by a number of trends. First, the speed of growth has been remarkable, especially during the period 2010–2018, when overall trends for FDI stocks in SSA were not so rosy. Over the course of this period, the overall inward FDI stock in SSA grew by 40 per cent, compared to an almost quadrupling of Chinese FDI stock.Footnote 15 In aggregate terms (all sources of FDI included), large African recipients of Western FDI (e.g. South Africa, Angola, Nigeria) experienced stock fluctuations over a flat line, or increasing and then fast declining FDI stocks after 2015, driven by the vagaries of the oil and other mineral extraction sectors. Ethiopia bucked that trend, partly thanks to fast-growing Chinese FDI into its manufacturing and construction sector – the country’s overall inward FDI stock swelled from $4.2bn in 2010 to over $38bn in 2023, with Chinese firms leading the way (Cheru and Oqubay Reference Cheru, Oqubay, Oqubay and Lin2019, 290). The rise of Ethiopia and other African countries as FDI recipients meant the combined share of FDI received by Angola, Nigeria, and South Africa dropped from 67 per cent in 2010 to only 30 per cent in 2023. In aggregate terms, China has jumped from not registering in statistics on FDI origin towards Africa up to fourth place, closely behind France, the USA, and the UK.Footnote 16

Figure 7 Chinese FDI stock in African countries (US$ bn)

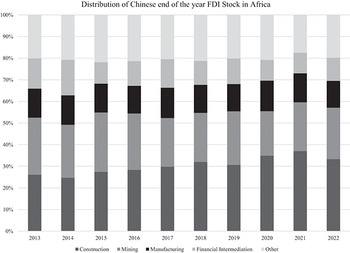

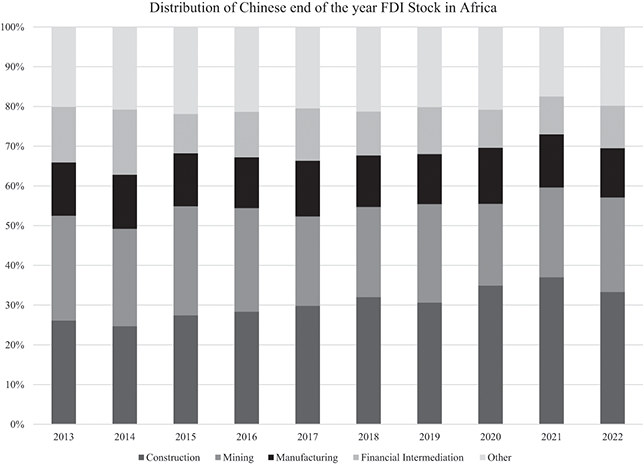

Second, the percentage of Chinese FDI stock in manufacturing is far from negligible but also largely underestimated in official records. This partly reflects the fact that the distribution of Chinese FDI tends to be more diversified than competing sources of FDI, which is generally more concentrated in energy-related industries (oil/gas extraction and infrastructure/supply services, and petrochemicals).Footnote 17 Although the aggregate percentage of Chinese FDI going into manufacturing (in terms of value rather than number of investment projects) has declined slightly, especially since 2019, in absolute terms it has continued to grow – from $3.5bn in 2013 to around $6bn in 2021.

Here, the reason for the percentage decline is the faster growth of FDI in construction (Figure 8), which is a logical trend given the progressive consolidation of Chinese infrastructure contractors in a larger number of countries in the years since the growth spurt began in the early 2000s. Once construction companies complete a number of projects in the same country, their next step is to establish a branch for further bidding, which is counted as FDI (Zhang Reference Zhang2023). In terms of number of greenfield projects, however, the proportion of investments directed at manufacturing is far higher – closer to a third (Shen Reference Shen2015). One of the most comprehensive surveys of Chinese firms in Africa, which counted around 10,000 companies, many of which outside MOFCOM records, estimated the share of manufacturing at 31 per cent (McKinsey 2017). This divergence from the shares based on value reflect the labour-intensive, smaller-scale nature of the manufacturing sector compared to capital-intensive sectors like mining and construction, as well as the significant number of unrecorded investment flows into manufacturing.

Figure 8 Distribution of Chinese FDI stock in Africa by value (%)

Third, China’s officially recorded FDI volumes remain too low to spur a dramatic industrial transformation in the medium run, even if a greater focus on manufacturing and construction may generate some level of industrial revival. Variation is important. While there have been visible effects on some countries (e.g. Ethiopia, Kenya, Ghana), the picture is less impressive when looking at Africa as a whole. Africa receives only a small proportion of total Chinese FDI, of which around 13–14 per cent goes to manufacturing, meaning the FDI’s aggregate-level contribution is still only moderate. Many African countries have received barely any Chinese investments in manufacturing, although most of these lack the basic conditions necessary to make manufacturing investments minimally profitable at an acceptable risk. By contrast, Ethiopia during the period 2010–2020 demonstrates the potential impacts of a much larger volume and proportion of FDI going to manufacturing. According to the EIC (Ethiopian Investment Commission) data, the share of manufacturing in terms of Chinese FDI value was close to 80 per cent for the period 1998–2018, a proportion replicated in terms of number of projects (Chen Reference Chen2024). This is a recent phenomenon, as even in Ethiopia – a leading recipient of Chinese industrial FDI – the flows only started surging after 2012 (Mamo Reference Mamo2024).

Overall, while there is a long way to go, the remarkable levels of foreign manufacturing investments directed at SSA in recent years demonstrate the potential of African countries when it comes to attracting substantial volumes of Chinese industrial investment (Sun Reference Sun2017).

2.3.2 What Kind of Manufacturing Investors and Why?

Sun (Reference Sun2017, 44) poses the question of why manufacturing in Africa is now attracting so much investment after decades of neglect. Her answer implies that two factors are at play: one structural and one individual. While the former is the classic latecomer advantage and ‘flying geese’ hypothesis, the latter points to entrepreneurs’ personal commitment and ingenuity (i.e. agency), particularly in situations where the risks involved would seem to discourage investment commitments. Let’s unpack the realities of Chinese manufacturing FDI in SSA.

Classification: ISI vs EOI Investors

Many authors have made reference to the ‘flying geese’ thesis, initially developed by Akamatsu (Reference Akamatsu1962) and often used to characterize FDI flows from Asia to Africa (Brautigam et al. Reference Brautigam, Tang and Xia2018; Lin Reference Lin2018; Calabrese and Tang Reference Calabrese and Tang2023). The thesis describes the phenomenon of delocalization, with entire production lines shifting location on the basis of cost and market expansion considerations. Here, the textile and apparel industry is frequently cited (Whitfield Reference Whitfield2022). This analogy is useful but insufficiently precise given the range of sub-sectors and drivers that Chinese varieties of capital display across different African countries, as well as the fact that the bulk of light manufacturing has remained in China despite some relocation overseas. In short, while many textile and apparel companies move to some African countries, textile and apparel exports from China remain strong. The ‘flying geese’ transition may therefore be a protracted process.

The effective reality of recent Chinese manufacturing FDI into Africa is that two distinct patterns can, to varying degrees, be discerned in different countries, dependent on the policy context and market opportunities. As explained in Section 1, the conventional contrast between ISI and EOI approaches and their sequencing describes the divergences in late development industrialization trajectories. This classification can also be applied to manufacturing FDI, given the different drivers and types of firms involved (for example, whereas some firms seek access to expanding African domestic and regional markets, others operate within GPNs and regard African countries as potential platforms for global exports).

The first type of manufacturing FDI – perhaps the most dominant in the present context – can be described as a manifestation of an ‘ISI path’, and is primarily concentrated in the building materials industries, basic household items and consumer goods. These investors are driven to tap into local market opportunities, which sometimes arise due to linkages with the construction sector boom, which may generate demand that cannot be met by imports only. Hirschman’s ‘induced demand’ signal plays a key role here, as importers and traders may capture opportunities to invest in domestic production facilities as a means of increasing their rates of return (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1958; Wolf Reference Wolf2024).

Several studies of Chinese manufacturing FDI into Africa suggest this ‘path’ is prevalent across a larger number of countries, particularly those with larger markets and limited manufacturing export experience, such as Nigeria and Angola (Geda et al. Reference Geda, Senbet and Simbanegavi2018; Xia Reference Xia2021; Chen Reference Chen2021; Calabrese and Tang Reference Calabrese and Tang2023; CABC 2024; Chen Reference Chen2024). Although the path encompasses a wide range of activities – from plastic recycling to plastic shoes, flip-flops and household goods – a large number of firms have focused on building materials, especially cement, bricks, ceramics and glass (World Bank 2012; Chen Reference Chen2021; Wolf Reference Wolf2024). Another key growth industry is furniture, which has been driven by Chinese traders with small export–import businesses in relatively large markets like Nigeria, as documented by Chen (Reference Chen2021).The range has been widening over time, suggesting the kinds of market opportunities and entrepreneurs are actually more variegated than previously assumed. For example, there is growing evidence of new plants being established for the manufacturing of consumer electronics and appliances, including handsets, or vehicle and equipment assembly, especially trucks and agricultural machinery (Brautigam et al. Reference Brautigam, Tang and Xia2018; Lu and Liu Reference Lu and Liu2018).Footnote 18 In most of these cases these investments are not crowding out local investors and hold the potential of turning into exporters to regional and global markets if plants are scaled up.

Chinese companies see potential in capturing a share of the substantial import (domestic) market currently served by Chinese goods. As such, it is often Chinese importers who decide to invest, especially when it comes to products that are particularly heavy and so more expensive to transport (cement, ceramics), or products requiring bulky raw materials that can easily be sourced locally, as in the case of furniture (lumber) and ceramics (clay) (Sun Reference Sun2017; Chen Reference Chen2021; CABC 2024, 22). Cement is a niche industry where Chinese manufacturers are exerting growing power across countries, from Ethiopia to Angola, and where sales by Western investors are opening new doors to Chinese capital as in Nigeria and Zambia.Footnote 19

Other traditional sectors, such as textiles, have also been subject to this ISI path, although with some contradictory shifts. In the case of the once-booming Nigerian textile industry, ‘Chinese industrialists helped create [it], then Chinese smugglers helped kill it’ (Sun Reference Sun2017, 41), only for a new wave of Chinese investors to revive it in order to exploit the growing size of the Nigerian domestic market and limited domestic competition (Chen Reference Chen2021). This shifting dynamic is also relevant to a range of consumer goods and household items (e.g. kitchen utensils, ceramics, plastics, foam mattresses, furniture), with small-scale local industries hit by Chinese imports from the 1990s trade liberalization (Meagher Reference Meagher2016), only to experience a revival partly and paradoxically driven by Chinese investors hitherto involved in the import business (Attah-Ankomah Reference Atta-Ankomah2016; Xia Reference Xia2021).

One advantage many Chinese manufacturers enjoy is their vast experience in consumer good and household item standardization, which enables simple imported technology to be efficiently produced at scale. A prominent example here is the Nigeria-based manufacturer that produces flip-flops at a lower unit cost than in China, beating the price any smuggler can offer (Sun Reference Sun2017, 47). Tang (Reference Tang2018) documents a similar dynamic in Ghana, where Chinese firms in the plastics recycling industry choose older or semi-automatic machinery for their Ghanaian operations due to the local market’s lower technical demands and a perception that Ghanaian workers are low skilled. In such circumstances, an important question to ask is whether domestically oriented Chinese manufacturers generate a net positive contribution to the industrial landscape, after considering potential crowding-out. On the basis of the recorded growth of these industries during the period when the investments took place, this appears to be the case. Nevertheless, there have been mixed outcomes. In Ethiopia, for example, Chinese-owned tanneries crowded out some local suppliers in the production of raw and semi-finished skins, while the government was trying to push these new investors to export finished products. These investors were more interested in exporting raw leather materials to their parent company in China than contributing to the effort of leather processed exports to Western markets (Mamo Reference Mamo2024). A similar phenomenon has been documented in the textile (fabric) sector of other West African countries (Nigeria, Ghana), as well as the production of basic household utensils (Sun Reference Sun2017; Tang Reference Tang2018; Chen Reference Chen2021). By contrast, in sub-sectors like cement, furniture, or pharmaceuticals, there is no evidence of crowding-out and fairly strong evidence of a net contribution to growth and complementarity with domestic firms (Oqubay Reference Oqubay2015).

The second characteristic modality of Chinese manufacturing firms is the EOI path, which is much less common given the barriers to participation in GPNs. The leading example is Ethiopia, although there have been some precedents in Mauritius, Kenya, Lesotho, and, more recently, Madagascar and Ghana. Sun (Reference Sun2017, 9) describes many of the entrepreneurs searching for new export platforms to continue their business and operations as ‘tough, gritty, unglamorous people living out adventure stories’. A survey conducted by Lin and Xu (Reference Lin, Xu, Oqubay and Lin2019) in China’s light manufacturing sector to gauge key push-and-pull factors found that rising labour costs are the core determinant, exacerbated by excessive competition in China and increasingly tight regulations, especially concerning environmental standards. This is consistent with what interviewees in the IDCEA project reported, with ‘push’ factors playing a more prominent role than the incentives provided by host African governments, or preferential trade agreements such as the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), aimed at providing easier access to the premium US market.Footnote 20