10.1 Introduction

The legal basis exists for a deeper focus on gender through the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).Footnote 1 The 2017 Joint Declaration on Trade and Women’s Economic Empowerment on the Occasion of the WTO Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires (Declaration)Footnote 2 was heralded as a landmark initiative for putting gender on the trade agenda,Footnote 3 and gender is also a strong focus of the African Union (AU) Agenda 2063.Footnote 4 Although in legal terms these are soft law instruments without binding obligations, they set the stage for deeper work globally and under regional trade agreements (RTAs) such as the AfCFTA. These instruments also align with important human rights instruments, including the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW),Footnote 5 UN Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), in particular, Goal 5 on Gender Equality,Footnote 6 and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol; also referred to as the AU Protocol on Women’s Rights).Footnote 7

RTAs are increasingly incorporating gender priorities,Footnote 8 sometimes in the form of more tangible commitments through gender-focused provisions and chapters.Footnote 9 Not only is this a global trend, but it has strong roots in the African continent, where substantive gender commitments are included in obligations through Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and ‘gender-sensitive trade policy has … been a distinct feature’ for years.Footnote 10 As of September 2022, the World Trade Organization (WTO) reported that out of 353 RTAs in force and notified to the WTO, 101 contain provisions on gender and women’s issues.Footnote 11 Among the recent RTAs that include gender provisions, several incorporate a separate gender chapter, such as the Chile–Uruguay, Canada–Chile, Argentina–Chile, Chile–Brazil, and Canada–Israel Free Trade Agreements (FTAs),Footnote 12 as well as the 2020 United Kingdom–Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement.Footnote 13 Some African RECs, such as the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and Southern African Development Community (SADD), as well as the Canada–Israel FTA, notably subject gender provisions to dispute settlement, which must often follow an attempt to pursue amicable avenues for resolving disputes.Footnote 14 While subjecting gender provisions to dispute settlement is a rather unusual feature among RTAs, it is likely that it is more cosmetic than compulsory.

Despite the proliferation of gender provisions and chapters, current approaches merely scratch the surface of what is possible. Most provisions on gender contain softer obligations and do not establish binding legal standards, which can be important for small enterprises and vulnerable communities. Further, gender provisions often fall short of enhancing equity and inclusion by not directly addressing the concrete challenges women face and the sectors in which they work. As gender chapters continue to evolve, they will likely be under increasing scrutiny regarding the depth of provisions, the degree to which they are gender responsive, and the extent to which they foster equitable and inclusive opportunities for women. This chapter will examine both current approaches and options for the future, with a particular focus on how trade rules could be designed to respond to the challenges that women traders, especially micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), face in their day-to-day work.Footnote 15

This assessment is critical in light of the announcement of a gender-related protocol under the AfCFTA,Footnote 16 which is the world’s largest RTA in terms of member states and is an agreement that has the potential to reset the rules well beyond the African continent.Footnote 17 Although the Protocol on Women and Youth in Trade under the AfCFTA is still taking shape, several provisions in the current AfCFTA provide a high-level glimpse into what may follow,Footnote 18 and some of these are quite innovative in their design. Treaties establishing other African RECs contain gender provisions as well, including the East African Community (EAC),Footnote 19 COMESA,Footnote 20 SADC,Footnote 21 Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS),Footnote 22 and Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS),Footnote 23 establishing a foundation on which to build.Footnote 24 Given some of the particular challenges facing women traders and entrepreneurs on the African continent,Footnote 25 including complex and inconsistent market rules and gaps in digital inclusion and access to finance, the AfCFTA provides a fresh opportunity to go beyond this start and address gender and trade in a meaningful way.

The sections below will examine RTA approaches on gender and trade to date, including the structure of RTA provisions on gender, the gender responsiveness of RTA provisions, and inclusive legal design approaches.Footnote 26 Together, these provide a comparative assessment of approaches, provisions, and legal design innovations (drawn from RTAs, WTO rules, hard and soft law, and domestic law) that could be used to address gender considerations in the context of inclusive development under the AfCFTA going forward.Footnote 27

The chapter unfolds as follows. Section 10.2 compares the approaches to assess trade and gender rules. Section 10.3 provides a contextual analysis of the options and innovations with respect to trade measures affecting women, access to finance, digital inclusion, and food security, under the AfCFTA and for future RTAs.

10.2 A Brief Comparison of Approaches to Assess Trade and Gender Rules

Although the practice and literature are still evolving on gender and trade, several approaches on how to assess gender and trade rules are relevant to the AfCFTA and other future RTAs. These include analysis of the structural nature of RTA provisions on gender, evaluation of the degree to which RTA provisions are gender responsive, and assessment of the equity and inclusivity dimension of gender and trade provisions. These different approaches intersect and are presented briefly below, and they all inform the contextual analysis in Section 10.3 focused on women’s needs in the market.

10.2.1 Structure of RTA Provisions on Gender

Structurally, the word ‘gender’ appears in RTAs in various forms (Table 10.1), including in agreements’ preambles and objectives (including, e.g., the Preamble to the AfCFTA); annexes; non-specific articles on related issues such as labour, agriculture, and intellectual property;Footnote 28 specific articles on gender; side agreements, which are often focused on related issues such as labour (e.g., Canada–Colombia and Canada–Costa Rica FTAs); and even stand-alone gender chapters (e.g., Chile–Uruguay FTA) in RTAs and protocols, such as the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development.Footnote 29 These structural aspects of gender and trade have been comprehensively assessed;Footnote 30 they inform how gender is incorporated into trade agreements, and they impact the degree and depth of commitments.

Table 10.1 Main structures of gender-related provisions

| Structure of gender-related provisions | Number of RTAs |

|---|---|

| Main text of the RTA: | 76 |

| Preamble | 12 |

| Non-specific article(s) on gender | 64 |

| Specific article on gender | 10 |

| Specific chapter on gender | 9 |

| Annex(es) | 17 |

| Side document(s) to the RTA: | 12 |

| Side Letters | 1 |

| Joint statement(s) | 1 |

| Protocol(s) | 2 |

| Labour cooperation agreement | 8 |

| Post-RTA agreements/decisions on gender: | 13 |

| Declaration(s) | 4 |

| Decision(s)/resolution(s)/directive(s) | 6 |

| Agreement(s) | 3 |

Within these structures, gender commitments tend to include common elements: ‘(i) affirmations of the importance of eliminating discrimination against women; (ii) recognition and adherence to other international agreements on gender; (iii) cooperation on gender issues (iv) institutional provisions including the establishment of committees for cooperation and exchange of information; and (v) soft committee-based dispute resolution mechanisms to amicably resolve differences’.Footnote 31

10.2.2 Gender Responsiveness of RTA Provisions

Going beyond structure, gender responsiveness is an important consideration in assessing RTA approaches. Bahri has advanced an instrumental Gender-Responsiveness Scale based on a maturity framework (Figure 10.1) which categorizes RTA provisions based on their gender responsiveness into five groups: limited, evolving, acceptable, advanced, and optimizing.Footnote 32 These benchmarks and levels allow for comparison across RTA provisions that go beyond their structure and begin to evaluate their impact.

Figure 10.1 Gender-responsiveness maturity framework.

Applying this framework to the AfCFTA, the AfCFTA contains Level I commitments in the Preamble (‘Recognising the importance of international security, democracy, human rights, gender equality, and the rule of law, for the development of international trade and economic cooperation’) and General Objectives (Article 3 (e) under the General Objectives contains the objective to ‘promote and attain sustainable and inclusive socio-economic development, gender equality and structural transformation of the State Parties’).Footnote 33 Even though the AfCFTA’s General Objectives contain a non-binding mention of gender equality, the inclusion of the language ‘promote and attain’ suggests a higher level of commitment than other general gender references.Footnote 34 Further, the language in the AfCFTA Preamble draws an explicit link between gender and ‘the development of international trade and economic cooperation’, implying that the AfCFTA as a whole should be interpreted in this context.Footnote 35

Notably, two of the AfCFTA’s protocols also contain gender-related provisions.Footnote 36 The AfCFTA Protocol on Trade in Services includes a reference to women in Article 27(2)(d) on Technical Assistance, Capacity Building, and Cooperation that could be considered a Level III commitment under Bahri’s scale (‘State Parties agree, where possible, to mobilise resources, in collaboration with development partners, and implement measures, in support of the domestic efforts of State Parties, with a view to, inter alia, … improving the export capacity of both formal and informal service suppliers, with particular attention to micro, small and medium size; women and youth service suppliers’).Footnote 37 The AfCFTA Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons contains a binding commitment with the use of mandatory language ‘shall’, stating that ‘States Parties shall not discriminate against nationals of another Member State entering, residing or established in their territory, on the basis of their … sex’.Footnote 38 This provision is particularly innovative, as it links non-discrimination with the free movement of persons and explicitly prohibits discrimination based on sex in this context.Footnote 39 The AfCFTA also includes a number of other provisions, including on special and differential treatment (S&DT), that could impact women as well (see Table 10.2).

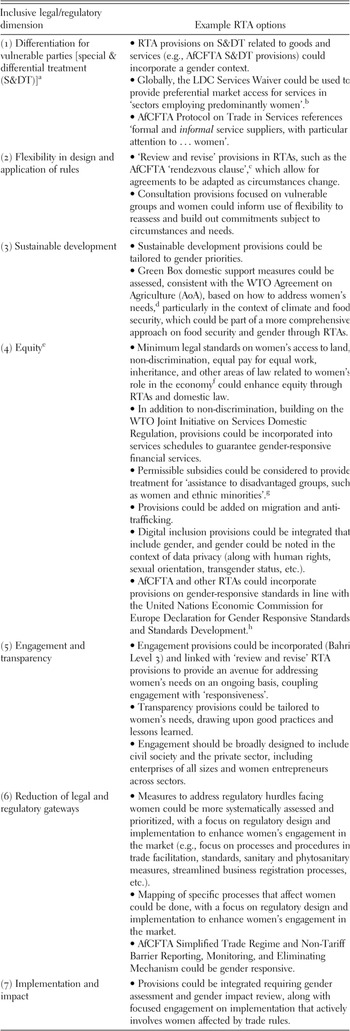

Table 10.2 Inclusive legal and regulatory approach

| Inclusive legal/regulatory dimension | Example RTA options |

|---|---|

| (1) Differentiation for vulnerable parties [special & differential treatment (S&DT)]Footnote a | • RTA provisions on S&DT related to goods and services (e.g., AfCFTA S&DT provisions) could incorporate a gender context. • Globally, the LDC Services Waiver could be used to provide preferential market access for services in ‘sectors employing predominantly women’.Footnote b • AfCFTA Protocol on Trade in Services references ‘formal and informal service suppliers, with particular attention to … women’. |

| (2) Flexibility in design and application of rules | • ‘Review and revise’ provisions in RTAs, such as the AfCFTA ‘rendezvous clause’,Footnote c which allow for agreements to be adapted as circumstances change. • Consultation provisions focused on vulnerable groups and women could inform use of flexibility to reassess and build out commitments subject to circumstances and needs. |

| (3) Sustainable development | • Sustainable development provisions could be tailored to gender priorities. • Green Box domestic support measures could be assessed, consistent with the WTO Agreement on Agriculture (AoA), based on how to address women’s needs,Footnote d particularly in the context of climate and food security, which could be part of a more comprehensive approach on food security and gender through RTAs. |

| (4) EquityFootnote e | • Minimum legal standards on women’s access to land, non-discrimination, equal pay for equal work, inheritance, and other areas of law related to women’s role in the economyFootnote f could enhance equity through RTAs and domestic law. • In addition to non-discrimination, building on the WTO Joint Initiative on Services Domestic Regulation, provisions could be incorporated into services schedules to guarantee gender-responsive financial services. • Permissible subsidies could be considered to provide treatment for ‘assistance to disadvantaged groups, such as women and ethnic minorities’.Footnote g • Provisions could be added on migration and anti-trafficking. • Digital inclusion provisions could be integrated that include gender, and gender could be noted in the context of data privacy (along with human rights, sexual orientation, transgender status, etc.). • AfCFTA and other RTAs could incorporate provisions on gender-responsive standards in line with the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Declaration for Gender Responsive Standards and Standards Development.Footnote h |

| (5) Engagement and transparency | • Engagement provisions could be incorporated (Bahri Level 3) and linked with ‘review and revise’ RTA provisions to provide an avenue for addressing women’s needs on an ongoing basis, coupling engagement with ‘responsiveness’. • Transparency provisions could be tailored to women’s needs, drawing upon good practices and lessons learned. • Engagement should be broadly designed to include civil society and the private sector, including enterprises of all sizes and women entrepreneurs across sectors. |

| (6) Reduction of legal and regulatory gateways | • Measures to address regulatory hurdles facing women could be more systematically assessed and prioritized, with a focus on regulatory design and implementation to enhance women’s engagement in the market (e.g., focus on processes and procedures in trade facilitation, standards, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, streamlined business registration processes, etc.). • Mapping of specific processes that affect women could be done, with a focus on regulatory design and implementation to enhance women’s engagement in the market. • AfCFTA Simplified Trade Regime and Non-Tariff Barrier Reporting, Monitoring, and Eliminating Mechanism could be gender responsive. |

| (7) Implementation and impact | • Provisions could be integrated requiring gender assessment and gender impact review, along with focused engagement on implementation that actively involves women affected by trade rules. |

a This most often takes the form of special and differential treatment, or special rights, for developing countries at the international law level. Kuhlmann, ‘Mapping Inclusive Law and Regulation’.

b Acharya et al., ‘Trade and Women’, 346.

c AfCFTA, Part. II Art. 7. See also Kuhlmann, ‘Mapping Inclusive Law and Regulation’, and Gammage and Momodu, ‘The Economic Empowerment of Women in Africa’.

d Acharya et al., ‘Trade and Women’, 337.

e Equity encompasses impartiality in law, with an emphasis on ensuring inclusivity for vulnerable groups addressing past injustices through law.

f See ITC, ‘What Role for Women in International Trade?’ (2019) <https://intracen.org/news-and-events/news/what-role-for-women-in-international-trade> accessed 2 May 2023; Kuhlmann et al., ‘Reconceptualizing Free Trade Agreements’. At the WTO level, this could take the form of a plurilateral agreement on women in trade, which could ‘codify the elimination of discrimination against women in trade [by eliminating] domestic laws that perpetuate such discrimination and ensur[ing] compliance with the principles of equal access and opportunity for trade’. Laura Lane and Penny Nass, ‘Women in Trade Can Reinvigorate the WTO and Global Economy’ (CIGI 27 April 2020) 6 <www.cigionline.org/articles/women-trade-can-reinvigorate-wto-and-global-economy/> accessed 8 May 2022.

g Acharya et al., ‘Trade and Women’, 342. They note that the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement) provides for significant policy space that could be used to empower women and disadvantaged groups.

h See Lane and Nass, ‘Women in Trade Can Reinvigorate the WTO and Global Economy’.

Yet, despite these innovations, the AfCFTA’s provisions on gender merely scratch the surface,Footnote 40 and movement towards an AfCFTA Protocol on Women and Youth in Trade could propel the AfCFTA in the direction of more comprehensive gender commitments, perhaps even reaching Level V on Bahri’s scale. As the following section will argue, an AfCFTA protocol could innovate beyond existing Level V commitments and be tailored to address particular challenges facing women traders and entrepreneurs in the market.

10.2.3 Inclusive Legal Design Approach

In addition to the approaches discussed above, another important aspect of assessing RTA approaches revolves around equity and inclusion in legal design.Footnote 41 To date, RTA provisions on gender, whether explicit or implicit, have focused primarily on cooperation and consultation and have not fully addressed more direct equity considerations.Footnote 42

Cooperation and consultations provisions are common in RTAs and are not limited to gender. They also appear in other RTA chapters, such as those on labour, the environment, SMEs/MSMEs, government procurement, agriculture, services, and intellectual property rights (IPRs).Footnote 43 These provisions fall within Level III in Bahri’s Gender-Responsiveness Scale and can be a useful tool when combined with other RTA commitments.

Assessing RTA design options through a lens of inclusion and equity requires a deeper dive into relevant legal design (encompassing a range of instruments, including treaties, soft law, domestic law and regulation, customary law, etc.), diverse legal and regulatory innovations, and the needs of vulnerable and marginalized stakeholders.Footnote 44 This is presented here based on an approach to ‘Inclusive Law and Regulation’ (Kuhlmann), applied to trade rules in a gender context (Table 10.2),Footnote 45 following an analytical framework that provides a basis to evaluate economic law and regulation (including RTAs) in the context of inclusive trade and development.Footnote 46 Additional options that fall within this analytical framework are presented in Section 10.3.

As Table 10.2 highlights, trade provisions and measures could be designed and applied based on a framework that fosters inclusion and equity. Additional examples that track these dimensions of inclusive law and regulation are presented in section 10.3.

Finally, and critically, there is also a political dimension to gender and trade. Despite the proliferation of gender provisions in trade instruments, gender and trade commitments are sometimes viewed with scepticism from the perspective of preserving policy flexibility (or ‘policy space’) and avoiding disguised protectionism.Footnote 47 These are important considerations and are approached here in three interconnected ways, recognizing that these issues are complex and multidimensional. First, states and regions need to consider the most appropriate way to use the legal instruments of international trade to meet particular gender and development needs. For this reason, the following section presents options for consideration and not prescriptive solutions. Second, as far as possible, any options for RTAs should be tracked with innovations in regional and domestic law, which can act as a proxy for supported principles and approaches. In this case, innovations in the design of African law at the international/regional and domestic levels are highlighted, bearing in mind that a more substantial review would be beneficial in the AfCFTA context. Finally, options presented in the following section are linked with actual challenges women face in sub-Saharan Africa, suggesting a balance between policy space and women’s needs and drawing a connection between RTA provisions and those they are meant to serve, ultimately linking macro-level trade agreements with micro-level challenges and opportunities. This final dimension is also worthy of greater study, as it is an important gap in trade law and trade agreements that should be more systematically addressed.Footnote 48

10.3 Contextual Analysis of Options and Innovations for the AfCFTA and Future RTAs

The preceding section presented a brief summary of three interconnected approaches to assess possible RTA provisions on gender and trade: a structural approach, a gender-responsive approach, and a design-focused approach based on inclusive law and regulation. This section draws from these approaches and frames RTA options for the AfCFTA in the context of challenges women face in the market. These challenges include issues related to the sectors in which women are engaged, including challenges related to work in both goods and services (and the high degree of work in the informal sector), non-tariff measures and regulatory hurdles, gaps in access to finance, lack of digital inclusion, and issues related to women’s role in the agricultural sector and food security.Footnote 49 Although current African RTAs (including the AfCFTA) do contain legal innovations, they do not fully recognize women’s particular needs or the roles that women hold in an economy, highlighting an important gap.Footnote 50 The AfCFTA could, however, innovate further through the new protocol and through a comprehensive, whole-agreement approach to address women’s needs.Footnote 51

Important lessons and options can be drawn from the design of both gender-specific and broader provisions in existing RTAs, WTO rules, and African law. The legal dimension of gender and trade should be comprehensively assessed across legal instruments (Table 10.3), although a full legal assessment is beyond the scope of this chapter. Assessing the legal dimension of RTAs must, however, go beyond RTA text, structure, and enforcement and extend to other international legal instruments and national law as well, encompassing the ‘various laws and norms that influence gender roles and women’s opportunities and constraints within a particular country’ (or region) (see Table 10.3).Footnote 52

Table 10.3 Legal instruments related to gender and trade

| Legal Instrument | Example |

|---|---|

| International instruments ‘relevant to gender equality and human rights’Footnote a | International treaties such as CEDAW, International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions, and the Maputo Protocol/AU Protocol on Women’s Rights; soft law, such as the UN SDGs (incorporated by reference in RTAs) |

| National constitutions | Constitution of Kenya (2010), for exampleFootnote b |

| National and subnational laws, regulations, policies, and other instruments ‘that benefit women and other disadvantaged groups’ | (a) Non-discrimination/equal treatment laws; (b) Affirmative action and laws to address gender disparity and promote equality;Footnote c (c) Laws related to fair wages, food labelling, and health and safety, as well as non-tariff measures in other areas, for example trade facilitation provisions; (d) Procurement rules related to women; and (e) Laws and regulations facilitating development of sectors in which women work (including agriculture, manufacturing, and services), as well as digital regulation and provisions on digital inclusion. |

| ‘Gaps or biases in the application or enforcement of laws that benefit women’ | Labour laws, land titling, banking regulationFootnote d |

| ‘Religious, traditional, or customary laws and practices’ (including ‘living law’) | Land tenure rules, inheritance rules |

a McGill, ‘Trade and Gender’, 37.

b Constitution of Kenya, 2010 (Laws of Kenya), Arts. 27(8), 59(2), 60(1)(f), 81(b), 91(f), 172(2)(b), 175(c), 197(1), and 250(11). With respect to government procurement, see also Constitution of Kenya, 2010 (Laws of Kenya) Art. 227(1) and Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act (Kenya), 2015, Section 53(6).

c According to McGill, ‘Trade and Gender’, fn 93, such ‘special measures aimed at accelerating de facto equality between men and women’ are expressly authorized under CEDAW.’ See CEDAW, Art. 4.1.

d Based on McGill, ‘Trade and Gender’, 38. McGill notes that ‘[f]acially neutral laws can … be applied in a discriminatory manner … [and] can also disadvantage women because of their more limited access to assets and employment opportunities’.

Domestic law is one of the most important sources of information on how RTA parties approach gender. Although states have innovative rules addressing gender, there are still critical gaps. According to the International Trade Centre, over 90 per cent of states have laws that limit women’s ability to engage in the market. These can take the form, for example, of rules and regulations that restrict women’s ownership of land, differentiated processes for business registration, and limitations on women’s participation in global trade.Footnote 53

In lieu of a comprehensive legal review, the WTO Trade Policy Review Mechanism (TPRM) provides important insight into how women’s empowerment is incorporated into the trade policies of WTO members.Footnote 54 Based on a sampling of TPR submissions, the majority (70 per cent) of members’ policies contain gender-responsive provisions.Footnote 55 These include (1) financial and non-financial incentives to the private sector and women-owned/led MSMEs and SMEs (30 per cent reported ‘trade policies that support women-owned/led companies’, including economic empowerment in the export sector; (2) ‘agriculture and fisheries policies that support women’s empowerment’ (15.5 per cent); and (3) ‘government procurement policies that support women’s empowerment’ (9 per cent).Footnote 56

Possible RTA options should further ‘be informed by an understanding of the social, economic and political context in which the relevant trade or investment activity is taking place, including the opportunities and constraints facing women and other disadvantaged groups’.Footnote 57 This aligns with an important aspect of gender mainstreaming, which calls for incorporating the ‘experience, knowledge, and interests of women … on the development agenda’,Footnote 58 as well as increasing focus on sectors that provide opportunities for women and ways in which to assist women-owned businesses to benefit from international trade and investment.Footnote 59

The sub-sections that follow discuss four priority areas: (a) women’s work in the goods and services sectors (including informal work) and trade measures affecting women (including impact of market rules on women); (b) access to finance; (c) digital inclusion; and (d) women’s responsibilities related to agriculture and food security, with relevant RTA options summarized. The options below track closely with the ‘inclusive law and regulation’ approach summarized in Table 10.2 and also integrate aspects of the gender-responsive approach in Figure 10.1. Although they relate mainly to the AfCFTA, they are applicable to other RTAs as well and also draw upon WTO disciplines as noted.Footnote 60

10.3.1 Women’s Work and Trade Measures Affecting Women

One of the most fundamental aspects of trade and gender centres around the nature of women’s work and engagement in the market. Women’s employment encompasses the goods and services sectors,Footnote 61 and women have faced considerable disruptions in respect of both goods and services work due to the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 62 A number of these challenges are due to the more precarious nature of women’s work, the lack of social safety nets, and women’s role in unpaid and informal work.Footnote 63 Tourism services, which are dominated by women, were also hit particularly hard during the pandemic.Footnote 64

Overall, women are increasingly involved in services, ranging from retail and financial services to tourism and hospitality, to health care,Footnote 65 including cross-border delivery of medical care that has been so critical during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women continue to play a strong role in manufacturing sectors as well, particularly export-driven manufacturing such as garments.Footnote 66

Women are disproportionately involved in the informal sector, and the United Nations (UN) estimates that 89 per cent of women in Africa work informally (as a percentage of full employment).Footnote 67 While informal work can sometimes be more flexible, it can also offer little security and room for advancement.Footnote 68 Within the informal sector, migrant women face some of the most significant challenges, as the pandemic has underscored.Footnote 69 The immense challenge of addressing trafficking of women and girls remains as well,Footnote 70 which is linked with trade and transport corridors and global value chains.

Women traders struggle with a number of regulatory roadblocks, or ‘regulatory gateways’,Footnote 71 that limit their participation in the markets. These include domestic rules and regulations that relate to non-tariff measures (NTMs) in the form of standards, sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures, and border measures, many of which are not gender responsive.Footnote 72 In terms of border measures, although the WTO Trade Facilitation AgreementFootnote 73 (and African governments) have pressed for simplification of measures and encouraged digitalization of border procedures in order to reduce waiting times, women traders still face procedural challenges and safety issues at the border.Footnote 74 Women traders also often lack information on cross-border regulations and procedures,Footnote 75 putting them at a disadvantage vis-à-vis larger businesses and subjecting them to delays at border crossings.Footnote 76 In addition, women tend to lack access to transport, which impacts opportunities for small-scale women traders, particularly those dealing in perishable goods (this was exacerbated during the pandemic due to border closures).Footnote 77

A number of RTA options could be considered to address women’s work and trade, as elaborated upon below.

For example, current RTAs tend to address women’s work more indirectly through provisions on labour, often including reference to the ILO Convention on Employment Discrimination.Footnote 78 While integrating ILO Conventions is important, this is just a start, and the AfCFTA and other future RTAs could incorporate both hard legal obligations and soft law instruments relevant to women’s work, such as UN SDG targets and indicators and business and human rights principles, enhancing the equity dimension of RTAs. Services commitments could be shaped in a gender context through horizontal commitments (spanning all services sectors) on non-discrimination,Footnote 79 strengthening the equity dimension of the AfCFTA. This would put the AfCFTA in a position to lead globally as well (aligning, for example, with the 2021 WTO Joint Initiative on Domestic Services Regulation that includes a provision to ensure that services measures ‘do not discriminate between men and women’).Footnote 80

The AfCFTA already incorporates differentiated treatment with respect to both goods and services, which is a notable innovation that could be built upon in a gender context.Footnote 81 In particular, the language in the AfCFTA Protocol on Trade in Services that mentions ‘formal and informal service suppliers, with particular attention to … women’,Footnote 82 is unique among RTAs and could inspire more binding commitments under the new protocol.

The AfCFTA could place special emphasis on women’s migration and trafficking in women and girls, innovating in these areas beyond current approaches. For example, the AfCFTA could include commitments in these important areas and incorporate other relevant instruments, such as the Ten Year Action Plan to Eradicate Child Labour, Forced Labour, Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery (2020–2030), adopted in February 2020 by African Heads of States and Government,Footnote 83 which aligns with AU Agenda 2063, and UN SDG Target 8.7. With respect to migration, the AfCFTA could include provisions on free movement of persons and give effect to aspects of the UN Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, including provisions on mutual recognition of qualifications for migrant workers (Global Compact Objective 18) and other aspects related to human rights, trafficking, and decent work.Footnote 84

Drawing upon lessons from the pandemic, the AfCFTA could also include provisions on essential services, such as procedural liberalizations, mutual recognition of professional qualifications, and use of green lanes for essential travellers, including service providers.Footnote 85

The AfCFTA could incorporate gender-specific non-discrimination provisions related to NTMs, such as gender-specific commitments on licensing requirements and licensing procedures for goods and services, along with qualification requirements and procedures in services.Footnote 86

The AfCFTA and other RTAs could incorporate provisions on gender-responsive standards, building upon the UNECE Declaration for Gender Responsive Standards and Standards Development.Footnote 87

Provisions on addressing NTMs could be strengthened and made more gender responsive, building upon existing innovations to reduce regulatory gateways including the AfCFTA Simplified Trade Regime and Non-Tariff Barrier Reporting, Monitoring, and Eliminating Mechanism, with parallels to the NTM mechanisms in African RECs such as the EAC, ECOWAS, and the Tripartite Free Trade Area, as well as the Simplified Trade Regimes (STRs) in COMESA and the EAC, and the EAC ‘Simplified Guide for Micro and Small-Scale Cross-Border Traders and Service Providers within the EAC’.Footnote 88 Going forward, these mechanisms could increasingly be approached from a gender perspective,Footnote 89 with implementation focused, in particular, on reducing barriers for women traders and linked to ongoing consultations to ensure that they are widely known and used in practice.

Transparency provisions could be tailored to increase information available to women traders and promote engagement and inclusiveness, expanding upon those included in Article X of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT),Footnote 90 as well as a number of RTAs.Footnote 91 Some areas of focus could include using designated contact points or enquiry points and formal and informal dialogue structures,Footnote 92 approached in a gender context.

The AfCFTA could also build upon trade facilitation provisions and the STRs to address women’s needs,Footnote 93 focusing on important regulatory gateways. Customs fast track lanes and green lanes, the latter of which appear in some of Africa’s trade corridors and have proven to be helpful during the COVID-19 pandemic,Footnote 94 could help facilitate trade for women, including small-scale traders, as could de minimis provisions to exempt trade below a certain monetary threshold from duties and other requirements. Further, RTA provisions could address the challenges women face in accessing services, such as transport.

The AfCFTA could include gender-specific references in the context of procurement in order to increase women’s participation in the market, consistent with the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement and AU proposal for a 40 per cent government procurement share for women,Footnote 95 as well as trends in African domestic law.Footnote 96 For example, Section 53 of Kenya’s recent Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act (2015) requires that 30 per cent of government procurement be reserved for women.Footnote 97 Because implementation of such commitments has already been flagged as a challenge, the AfCFTA could include provisions on implementation, actively engaging women in tracking whether these commitments are applied in practice.

Across all areas, the AfCFTA could also require collection of sex-disaggregated data and gender impact assessments of trade rules, consistent with articulated continental priorities and the WTO Declaration.Footnote 98 The degree to which AfCFTA provisions are binding and subject to dispute settlement will also be an overarching area for further consideration.

10.3.2 Access to Finance

Across the African continent, women face challenges in accessing affordable finance and credit,Footnote 99 which often acts as a factor limiting women’s work and trade (for example, lack of finance could keep women involved in the production of low value-added, unprocessed agriculture instead of processed products with a higher premium in regional and international markets) and opportunities for specialization, growth, and entrepreneurship.

Further, limitations on women’s ownership of land limits women’s access to credit and economic opportunities. Collateral requirements tend to favour land-based collateral, and in doing so disadvantage women due to restrictions on women’s landownership.Footnote 100 When combined with strict financial sector loan conditions, high interest rates,Footnote 101 and lack of tailored financial services products for women, these restrictions can limit women to informal cross-border trade without sufficient opportunities to engage in the market.

A number of RTA options could be considered to address access to finance for women.

For example, RTA parties could agree to horizontal commitments to reduce gender-based discrimination and improve women’s access to services (equity-enhancing provisions), as noted in Table 10.2 and Section 10.3.1.

RTAs, including the AfCFTA, could enhance equity by introducing binding rules related to gender, as noted in Table 10.2, which are consistent with REC provisions in a number of contexts.Footnote 102 These could include access to land, inheritance, and even expanded rules on collateral, including perhaps lease financing, acceptance of moveable property and contracts as collateral, and creation of an electronic collateral securities registry,Footnote 103 which could be done in a gender-responsive way. Binding rules could address other areas as well, such as non-discrimination and equal pay for equal work, which would reinforce the other options in this section and help ensure that RTAs are designed to support equity and inclusion. While these rules would address significant aspects of access to finance, they would be important all across women’s work and livelihood.

RTA parties could agree to financial services commitments to encourage gender-responsive financial services products. These could include services sector commitments, both horizontal and sector specific. They could also emphasize important aspects such as mobile money, which has significant implications for women traders.Footnote 104

Some African states, including Burundi, Egypt, Nigeria, and Zambia, have put in place policies that promote financial inclusion and gender-inclusive finance,Footnote 105 highlighting national-level support in this area and areas in which the AfCFTA could build out pan-African commitments. Training and building awareness on access to finance could be linked with the AfCFTA, including through ongoing initiatives, such as the African Development Bank’s Affirmative Finance Action for Women in Africa (AFAWA) programme and 50 Million African Women Speak Platform (50MAWS). Over time, the AfCFTA could become a platform for financial education and regulatory alignment.Footnote 106

10.3.3 Digital Inclusion

Addressing digital inclusion and inequality in digital trade will be significant across all aspects of women’s economic engagement.Footnote 107 Although women stand to gain significantly from digital trade, they are also particularly affected by the digital divide.Footnote 108 Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and financial services, including online payments services, could be better leveraged by women entrepreneurs and traders.Footnote 109 However, this also depends upon physical infrastructure and access to the internet.

Digital inclusion and opportunities in digital trade go hand in hand, and digital opportunities could be better harnessed to the benefit of women entrepreneurs and in furtherance of the UN SDGs,Footnote 110 namely UN SDG 5 and Target 5.b: ‘Enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular ICT, to promote empowerment of women.’Footnote 111 Digital trade has already been highlighted as a priority issue for the next phase of the AfCFTA, with a digital trade protocol under negotiation,Footnote 112 which, in tandem with the gender and youth protocol, provides an opportunity to address digital inclusion and consider ways in which to tailor provisions to address women’s needs.

RTAs could address digital inclusion in a number of ways.

Although few RTAs deal with digital inclusion, the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) among Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore (China and South Korea have also initiated the process of joining)Footnote 113 includes specific language that emphasizes digital inclusion for indigenous communities, women, rural populations, and low socio-economic groups.Footnote 114 The DEPA explicitly references gender in the context of digital inclusion: ‘To this end, the Parties shall cooperate on matters relating to digital inclusion, including participation of women, rural populations, low socio-economic groups and Indigenous Peoples.’Footnote 115 The DEPA goes on to state that ‘cooperation may include’ a number of things, such as sharing experiences and good practices, ‘promoting inclusive and sustainable growth’, ‘addressing barriers in accessing digital economy opportunities’, and others.Footnote 116 The cooperation aspect of the DEPA bears similarity to the cooperation provisions in existing gender and trade provisions and chapters, and this language provides a baseline upon which to build more performative obligations in the AfCFTA and future RTAs. The draft negotiated text for the Partnership Agreement between the European Union and the members of the Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (OACPS) also contains important provisions on reducing the digital divide and supporting digital entrepreneurship, particularly by women and youth.Footnote 117

African national policies and rules on financial digital inclusion, such as those in Mozambique, Madagascar, Tanzania, and Zambia,Footnote 118 show national support for digital inclusion that could pave the way for broader strategies under the AfCFTA.

Gender needs could also be explicitly taken into account in the context of data protection, and the UN Human Rights Council and the UN General Assembly have called upon UN members to ‘develop or maintain … measures … regarding the right to privacy in the digital age that may affect all individuals, including … women … and persons in vulnerable situations or marginalized groups’.Footnote 119 Within African regional law, the ECOWAS data protection rules reference human rights and ‘fundamental liberties’ of the data holders,Footnote 120 which is also notable and could be even further tailored to gender. Some countries’ laws contain innovations in this area, including India’s Personal Data Protection Bill (2019), which, if passed into law, would treat data on health, caste or tribe, sexual orientation, and transgender status with heightened privacy protection.Footnote 121

10.3.4 Agriculture and Food Security

African women play many roles in the agricultural sector – as primary producers of food and providers for their households, and also as traders and processors of agricultural products – creating strong links between agricultural trade and human rights, food security, health, livelihoods,Footnote 122 and, of course, the SDGs.Footnote 123 In sub-Saharan Africa, women tend to be primarily responsible for household food security, in addition to their involvement in the production of both cash and subsistence crops.Footnote 124 Non-traditional agricultural exports, such as cut flowers and fruit and vegetables, present enhanced trade and work opportunities for women, and, in the case of non-traditional food crops, they can provide important benefits in terms of food security as well.Footnote 125 However, trade’s differential impact on women needs to be carefully considered, particularly in the agricultural sector where export-oriented agriculture can displace women-dominated subsistence farming.Footnote 126

Despite their prominent role in the agricultural sector, women continue to struggle with limited landownership and access rights and challenges with access to credit.Footnote 127. Women’s limited access to agricultural inputs, including seeds, technology, and extension services, impacts the ability to transition into higher value-added production and ultimately benefit from trade opportunities.Footnote 128

Women also tend to face particularly challenging regulatory hurdles in the agricultural sector, including compliance with standards and SPS measures, which can require significant investment, economies of scale, and technical capacity.Footnote 129 The WTO SPS Agreement, with which most RTAs largely align, including African RECs and the AfCFTA, contains important disciplines and an emphasis on capacity building and S&DT.Footnote 130

There are a number of RTA options for integrating agriculture and food security.

For example, the AfCFTA could include provisions reaffirming the space for governments to put in place gender-responsive domestic support measures related to agriculture that are consistent with AoA ‘Green Box’ measures, such as training, research, extension, and advisory services.Footnote 131 A gender lens could also be applied to agricultural input subsidies for resource-poor farmers in line with Article 6.2 of the AoA.Footnote 132

The AfCFTA, building upon the precedent created through the RECs, is scheduled to address agricultural inputs in a more comprehensive way, creating another avenue for gender-responsive domestic support commitments and other provisions, including enhanced gender representation on inputs committees, that would complement the new protocol on gender.

While RTAs have not comprehensively addressed food security, this is an area that could be pioneered under the AfCFTA in line with broader sustainable development considerations and the SDGs.Footnote 133 Food security could be addressed more comprehensively through detailed provisions on export restrictions, safeguards, tailored domestic support, climate adaptation, and links with agricultural inputs and other areas of regulation,Footnote 134 all of which could be aligned with WTO disciplines and other areas of international law and approached through a gender and equity lens.

RTA measures to improve transparency and enhance capacity building could be strengthened, enhancing engagement and inclusion, with a particular focus on women’s role in the agricultural sector. This could work in tandem with tools for notifying and responding to SPS issues, such as the AfCFTA Simplified Trade Regime and Non-Tariff Barrier Reporting, Monitoring, and Eliminating Mechanism, and other programmes noted, in addition to the ePing Alert System of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs and ITC that improves access to SPS and TBT regulations, including through SMS alerts for small traders.Footnote 135 These programmes could all be tailored to women’s needs.

10.3.5 Overarching RTA Options

Finally, several RTA design options could address challenges across the four areas that are the focus of sections 10.3.1, 10.3.2, 10.3.3, and 10.3.4. These include cooperation and consultation provisions, which are already present in current RTAs (these align with Bahri’s Gender Responsiveness Levels III and IV and Kuhlmann’s Engagement Dimension of Inclusive Law and Regulation), and can be important across priority areas to promote enhanced skills, entrepreneurship, access to finance, and bridging the digital divide, among others.Footnote 136 Capacity-building provisions, while common in RTAs, could be enhanced to include the creation of gender committees and application of good practices and standards, as well as the collection and use of sex-disaggregated data.Footnote 137 However, while consultation, cooperation, and capacity-building provisions are important,Footnote 138 these mechanisms alone are insufficient to directly address women’s needs. These RTA options should be considered in combination with binding commitments (and softer commitments where appropriate) discussed in particular in Section 10.3.2 that would establish more performative obligations likely to lead to concrete action and provide a clearer channel for women to exercise rights.

RTAs could also address gender on a more systemic level, drawing from pan-African priorities and proposals at the global level, the latter of which includes a possible plurilateral agreement on trade and gender. Both multilateral and regional rules could incorporate expansion of general exceptions clauses modelled on GATT Article XX, which many RTAs, including the AfCFTA, contain.Footnote 139 While this could be helpful for incorporating gender and leveraging policy space, exceptions should not take the place of affirmative commitments on gender and trade. Finally, comprehensive gender strategies at the national and regional levels and use of gender-disaggregated data should be widespread practices. On the African continent, the UN has emphasized that gender mainstreaming needs to be integrated into the operationalization of the AfCFTA through countries’ national implementation strategies,Footnote 140 a proposal that would support many of the options discussed in this chapter.

10.4 Conclusion

As this chapter illustrates, gender-responsive rules can promote inclusive trade and development and generate significant benefits for women; however, the design and implementation of these rules will be critical. The AfCFTA already has a solid foundation on which a new gender-focused protocol could build, drawing from inclusive legal design options and innovations and broader lessons learned within and outside of the African continent to address real challenges in women’s work and trade, access to finance, digital inclusion, and agriculture and food security. The options highlighted in this chapter attempt to balance between policy discretion and establishment of binding commitments that would give greater certainty to women-led MSMEs and SMEs. The AfCFTA holds great promise, both in enhancing existing innovations in legal design and in ensuring that women’s voices are heard as new trade rules are developed and existing rules are applied. The options for inclusive law and regulation presented in this chapter, which could be incorporated into new RTA chapters and protocols or combined into an inclusive whole-of-agreement approach, provide an entry point for gender-responsive trade provisions and an opportunity for resetting the rules on gender and trade.