Crony neoliberalization, a weak informalized state and a deficit of legitimacy has shaped the everyday practices of governance, legitimation and contestation in Egyptian schools. Deteriorating socioeconomic conditions and the weakening of state institutions in the late Mubarak era informed how the regime rearticulated its citizenship discourses. The attempt to consolidate a new elite around Gamal Mubarak and to prepare him to take over after his father deepened the deficit of legitimacy and accentuated the cleavages within the elite and the security services, culminating in the 2011 Revolution. This chapter lays out this broader political context, the resulting state of education and the approach of the study. The first part of the chapter explains the key overarching features of the Mubarak era, highlighting both socioeconomic changes and changes in nationalist and ideological narratives. The second section provides essential background on tracking, quality and equity in the education sector, especially as crystallized in secondary schooling. It outlines the evolution of nationalist and ideological narratives in textbooks and schools and the securitization and Islamization of education. The third section details how the schools were selected for this study, which socioeconomic groups they cater to, how I conducted the research before and after the uprising, the dynamics of my own insertion into the schools, the selection and analysis of textbooks and the most significant limitations of the research.

Transitioning to Neoliberalism

In the early years of his rule, Mubarak relied on the general political direction he inherited from his predecessor Anwar Sadat (in power 1970–81). This included moving away from the state socialism of the Nasser era (1952–70), the slow adoption of policies of economic liberalization, token measures of political liberalization, rapprochements with Islamist groups and the consolidation of Egypt’s alliance with the United States. The policies of structural adjustment and economic liberalization initiated in 1991, with their roots in Sadat’s Infitah policies of the 1970s, resulted in significant changes in the Egyptian economy and nature of the social contract. They entailed a retrenchment of the state from social protection, basic infrastructure and public service provision. Social expenditure lagged far behind the rapid growth in population, declining from 34 percent of GDP in 1982 to an average of 17 percent in the 2000s (El-Meehy Reference El-Meehy2009, 14). The late 1990s brought about fundamental changes to rural Egypt, essentially reversing the land reforms set in place since 1952 and causing increased landlessness and rural poverty (Bush Reference Bush2002). However, levels of growth and job creation were not high enough to balance these negative patterns. The government was also not able to achieve the chief aims of these economic policies in terms of lowering its levels of debt and expanding its exports (Abo El-Abass and Gunn Reference Abo El-Abass and Gunn2011), thereby creating pressure for even more austerity measures.

A new set of critical changes characterized the last decade of Mubarak’s rule, what I refer to as the late Mubarak era. A wave of pro-business liberalization and privatization began around 2003/2004 with the appointment of the Nazif government, which was removed by the January 2011 protests. In 2005, new taxation policies effectively removed any semblance of progressive taxation, capping all taxes at 20 percent (Diab Reference Diab2016). In March 2007, the Constitution was finally purged of references to socialism and replaced with the declaration that “the economy of the Arab Republic of Egypt is founded on the development of the spirit of enterprise.” From 2002 onward, under the leadership of his son Gamal Mubarak, official papers of the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) began to claim that the state’s provision of basic services had led to deterioration in their quality, and that the solution was to open education and health to private investment. The so-called New Thought of the party involved finding ways to divest the state of its “burdens” on those fronts. As measured by the Human Opportunity Index, access to basic services, although unequal, had actually improved in the decade before the uprisings (Ersado and Aran Reference Ersado and Aran2014). However, the nominal increase in access was accompanied by deterioration of quality and informal privatization. In the education sector, for example, Egypt achieved higher enrollment in basic education as well as greater access to university education (UIS Online). This nominal expansion in access is structured by the decline in quality and equity, most blatantly reflected in Egyptian students’ ranking as second to worst in the world in reading and writing skills (Mullis et al. Reference Mullis, Martin, Foy and Hooper2017), and the earlier indicators discussed in the following sections.

The changes of the late Mubarak era critically included the intention to pass on the presidency to Mubarak’s son, Gamal, as signaled especially by the constitutional amendments in 2005, which paved the way for his succession. Changes in the political landscape involved a significant reshuffling of the so-called old guard of the ruling elite and the rise of a new guard associated with Gamal. His selected associates from the business community were installed in the ruling party’s Policy Secretariat and eventually appointed in key ministerial positions. The regime had arrived, especially after 2003, at a formula for maintaining its hold on power while offering selective benefits to a changing and ever narrowing power base. New forms of patrimonialism and clientelism were manifested in the flagrant manner in which the 2010 parliamentary elections were rigged in order to create a loyal parliament without opposition. This event is privileged in some accounts of the 2011 Revolution as a critical trigger for the protests – including, incidentally, the account of the Revolution in the 2016 textbooks.

Corruption, informality, low wages and unemployment were four defining of the late Mubarak era. Coupled with austerity and privatization, these trends translated into a transformation in the quality of key public services like health and education, transportation, municipal services and law and order. Corruption intensified in all layers of public as well as private institutions under Mubarak, especially during the last 10 years of his reign (Amin Reference Amin2009, Alissa Reference Alissa2007, Ismail Reference Ismail2011a). A breakdown of the rule of law underpinned the institutionalized corruption that had become endemic in public institutions under Mubarak (Amin Reference Amin2009), reaching unprecedented levels by global standards (Chekir and Diwan Reference Chekir and Diwan2015). Linked to corruption, informality is the other form of permissiveness or retraction of the rule of law that defined the Mubarak era. Scholarly work on informality in Egypt has focused especially on informal neighborhoods (Singerman Reference Singerman1995, Elyachar Reference Elyachar2005, Ismail Reference Isin, Turner, Isin and Turner2006, Dorman Reference Dorman2007, Sabry Reference Sabry2010), where housing is constructed without official permits, key services are accessed by illegally tapping into the official means of provision, and all this is done with the complicity of state officials, typically in return for direct payments, bribes and favors. As Dorman (Reference Dorman2007) puts it, informality opens the door to the kind of clientelism in search of access to public services upon which the micropolitics of many Cairo neighborhoods revolves. The size of the informal sector in Egypt, in which workers have no legal protection, has increased continuously from the 1980s to the present day, currently representing an estimated 70 percent of economic activity (OECD 2018, Elshamy Reference Elshamy2018, AfDB 2016). Young people in particular have been severely impacted by informality in the labor market. In fact, young Egyptians have become the most disadvantaged group in terms of higher rates of unemployment, lower earnings, and limited job security and stability, with the majority of new entrants finding jobs in the informal economy (Assaad and Barsoum Reference Assaad and Barsoum2007). By 2006, initial employment in the informal sector represented half the jobs obtained by female commercial-school graduates, a phenomenon that was virtually nonexistent three or four decades earlier (Amer Reference Amer2007). Those whose first job after graduating is in this sector generally find themselves unable to transition into formal-sector employment; 95 percent of those who were employed in informal jobs in 1990 were still in those or similar jobs in 1998 (Mokhtar and Wahba Reference Mokhtar, Wahba and Assaad2002, cited in World Bank 2003, 83).

Unemployment has had a disproportionate impact on educated youth in particular. Although it is difficult to rely on official measures of unemployment in the midst of informality and underemployment, existing data show a crisis of unemployment, especially affecting better-educated young people and women. According to official statistics, in Egypt the rate of youth unemployment (as a percentage of the total labor force aged 15–24) from 1990 to 2003 ranged from 20 to 30 percent (World Bank 2019c).Footnote 1 After 2003, and especially since 2010, youth unemployment increased to 35 percent, and female youth rates and withdrawal from the labor market significantly exceed male rates.Footnote 2 The unemployment rate of young people with advanced education (university) ranged from 51 to 63 percent over the period from 2008 to 2017, while the rate of those with intermediate education (secondary) ranged from 39.7 to 29.9, and those with basic education from 6.7 to 21.5 (ILOSTAT 2019). However, in the case of young females, it is not those with the highest levels of education that show the highest unemployment rate but those with intermediate levels (Barsoum et al. Reference Barsoum, Ramadan and Mostafa2014, 30). Because jobs are scarce and of such low quality, a large proportion of young people have had to stop searching for work and are therefore counted as “out of the labor force,” not among the “unemployed.” It is therefore the educated middle-class youth who suffer the most from unemployment, while less-advantaged youth suffer from precariousness, poor pay and poor working conditions.

Low wages are at the core of Egypt’s economic and social problems, and public-sector wages have been declining in real terms for decades (Abdelhamid and Baradei, Reference Abdelhamid and Baradei2010). Critically, the increasing inequality of wage incomes from 1998 to 2012 has been accompanied by the impoverishment of the middle classes (Assaad et al. Reference Assaad, Krafft, Roemer and Salehi-Isfahani2016). Wage polarization within the public sector accompanied wider patterns of declining real wages, increasing precariousness and informalization. As senior public servants and selected cadres were courted with annual bonuses and raises, an increasing proportion of staff were being hired on differentiated temporary contracts, which offered varying pay structures and minimal wages below the poverty line (such as teachers receiving monthly wages of 100–350 EGP, i.e. 15–50 USD). Household welfare declined for most households between 2000 and 2009. Households reported feeling poorer and the mismatch between welfare expectations and actual welfare increased (Verme et al. Reference Verme, Milanovic and Al-Shawarby2014, 6).

This deteriorating political, economic and social situation was not met with silent approval. Popular protest and oppositional movements grew over this period, especially after 2003. From 1998 to 2011, more than two million workers participated in some 3,500 strikes, sit-ins and other forms of protest, with major strikes in nearly every sector of the Egyptian economy (Beinin Reference Beinin2011). Importantly, however, in the 2000s, unlike the 1980s and 1990s, the government did not routinely repress workers’ protests through massive use of violence and typically offered limited concessions to protestors, creating the perception that protesting generated significant gains (Beinin Reference Beinin2011). Reports of police violations and different forms of corruption played a pivotal role in exposing state repression and mobilizing for protest. The growth of independent and citizen media has been critical in this regard, with the emergence since 2003 of some two dozen new newspapers and magazines independent of the regime, offering, along with the Arab satellite stations and the Internet, access to information that was unimaginable a decade earlier (Beinin Reference Beinin2009, Meital Reference Meital2006). This protest movement culminated in the 25 January Revolution, which prompted Mubarak’s removal in 2011.

Political contestation was met with different forms of repression by the state, ranging from the imprisonment of well-known opposition figures like Ayman Nour, to the extension of state security oversight to every sector of society, including schools. Mubarak built on and advanced the authoritarian legacy he inherited from his predecessors. Since coming to power in 1981, Egypt has been ruled under a declared State of Emergency, whereby the regime “has rationalized the outlawing of demonstrations, the use of indefinite detentions without trial, and the endowment of presidential decrees with the power of law” (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2002, 6–7). The repression of opposition was also carried out through various forms of intimidation, detention and torture. While the regime’s Islamist opponents have been the largest recipients of this repression, secular political activists, human rights activists, organized workers and regular voters have all been targeted, which could be viewed “as an indication of the increasing insecurity of an authoritarian regime determined to maintain its monopoly on power” (Kassem Reference Kassem2004, 187). Oppositional action that “takes to the streets” and organized action that involves oppositional Islamism, especially activities that brought Islamists together with secular activists, were the critical “red lines” that defined the freedoms allowed by the regime (Kassem Reference Kassem2004). Apart from political repression, however, violent and humiliating treatment, and different forms of extortion by police and other state officials, permeated citizens’ daily lives (Ismail Reference Isin, Turner, Isin and Turner2006). These everyday violations varied greatly based on social class position, where the poor were on the receiving end of the largest share of a wide range of repressive practices. As the late Hani Shukrallah put it,

[T]he middle-class professionals in Kifaya can chant slogans like ‘Down with Mubarak’ because they risk, at worst, a beating. But most Egyptians live in a world where anything goes, where they’re treated like barbarians who need to be conquered, and women are molested by the security forces. The average Egyptian can be dragged into a police station and tortured simply because a police officer doesn’t like his face.

It is this everyday vulnerability and repression that occupies this study of lived citizenship. The overall transformation since the late Mubarak era is broadly conceived as redirection of the functions and resources of the police toward regime security and away from the regular functions of public security (see Abdelrahman Reference Abdelrahman2017). This is translated in the sense of diminished access to policing functions for the poor, with the revival of communal arbitration methods and reliance on private security for those who can afford it (see Ismail Reference Isin, Turner, Isin and Turner2006, Reference Ismail2012).

From Socialist Arabism to Neoliberal Islamism

These major social and economic changes were accompanied by shifts in official narratives of national belonging and ideological legitimation. These narratives entailed updated conceptions of the nation, the people, the army and Islam. Understanding these shifts requires an overview of their transformations since independence from the British in the 1950s. In 1952, Nasser and his colleagues in the Free Officers Movement swiftly removed the monarchy and succeeded in expelling the British from Egypt, proclaiming a revolution led by the army and supported by the people. Their rise to power ushered in the privileged political and economic position of the army and its place in nationalist discourses. State socialism and Arab nationalism developed into the key ideological pillars of the Nasser regime (1952–70) and the bases upon which notions of national identity and citizenship were articulated, including in school textbooks. The route to national renaissance was constructed with reference to an ideal of unity in support of the July Revolution’s goals of lifting poverty, raising incomes, eliminating class differences, and providing work and educational opportunities to all (Brand Reference Brand2014). Nasser’s legacy and popularity stemmed in large part from the expansion of a universal and free education system and public health services, massive investments in infrastructure, housing market regulations, guaranteed employment and job security for the educated classes, the expansion of the social insurance system, and partial land redistribution and an industrialization program, all creating a legacy of social mobility, a more egalitarian distribution of wealth and a decline in poverty (Waterbury Reference Waterbury1983). With economic liberalization under Sadat and the shift in alliances from the Soviet Union to the United States, official references to the declared principles of the July Revolution quickly receded. From Mubarak’s first speech, there was no more talk of class struggles or even “closing income gaps,” but rather of desiring to “meet basic needs” in a shared responsibility with Egypt’s citizens and their “spirit of initiative” (Brand Reference Brand2014, 94).

Islam has always been an integral component of the Egyptian state’s nationalist discourse and a critical pillar of regime legitimacy. The nature and extent of the use of Islam and IslamismFootnote 3 in the crafting of Egyptian national identity and in the broader cultural and moral canvas has varied considerably over time, including in educational discourses and textbooks. The turn toward alliances with Islamism and the greater Islamization of the public sphere started under Sadat (1970–81), primarily to compete with the popularity of Nasser’s Arab Socialism. Embracing the Islamic referential was also “instrumental in Egypt’s alignment with the petro-monarchies” and well suited to the increasing labor migration to the Gulf (Roussillon Reference Roussillon and Daly1998, 393). Already in the 1971 Constitution, sharia was declared “a” primary source of legislation, and by 1980 this had been amended to “the” primary source. “Science and faith” were explicitly articulated as the basis of Egypt’s progress, renaissance and national identity. As early as 1971, Sadat began his speeches with “In the name of God” and addressed his audience as “brothers and sisters,” rather than Nasser’s “citizens” or “brother citizens.” By 1978, he declared himself to be responsible first and foremost to God, marking a departure from Nasser’s construction of the Egyptian people as sovereign and as citizens (Brand Reference Brand2014). Because Sadat’s reign was very short on account of his assassination by violent Islamist groups in 1981, the implications of this policy direction only became clear under Mubarak. In fact, Alain Roussillon has argued that for Sadat, Islamization of legislation was mere gesturing, whereas for Mubarak, Islamizing the framework of Egyptians’ daily lives was perceived as a means of quelling Islamism itself (Roussillon Reference Roussillon and Daly1998). This opening toward Islamist forces included the informal integration of “moderate” Islamists into the formal political scene through political parties and professional associations (Campagna Reference Campagna1996).

The configuration of Islamist forces exerting an influence on the public sphere did not remain constant throughout the Mubarak era. In the 2000s, the regime encouraged and gave space to a different constellation of Islamisms. Preachers who did not put forward oppositional discourses were allowed to publish in state-sponsored magazines, preach and give lessons in large mosques, university campuses, community assistance associations and religious satellite channels with wide viewership. Their emphasis was on personal morality, chastity, modesty, charitable and voluntary work, and industrial and business entrepreneurship. This increasingly hegemonic mainstream Islamism retained the “Islamist Creed” that faithful adherence to Islam is the route to power and prosperity, but it depoliticized Islamism by ignoring the role of the state in anything from applying sharia to guaranteeing social, economic or political rights (Sobhy Reference Sobhy and Singerman2009). The regime also tolerated and gave space to more conservative Salafi groups and preachers. These groups also emphasized individual morality and stricter controls on modesty and the mixing of genders. They forcefully condemned protest and often democracy, and propagated obedience to the ruler. Despite periodic limitations, both the non-oppositional Salafi trend and the more elite Islamism of the so-called new preachers like Amr Khaled were allowed far greater margins of freedom than other oppositional Islamist trends (Wise Reference Wise2003, Haenni and Tammam Reference Haenni and Tammam2003, Sobhy Reference Sobhy and Singerman2009). These non-oppositional Islamisms cohered with the regime’s neoliberal and authoritarian projects, as well as its regional and global alliances (Sobhy Reference Sobhy and Singerman2009). Paradoxically, in this period, the regime also invested in a project of “enlightenment” and “cultural cultivation” (tanwir and tathhqif) led by secular-oriented intellectuals who attempted to engage youth in art, literature and cultural activities, workshops and competitions (Winegar Reference Winegar2014). This was arguably motivated by a desire to appease and draw legitimacy from secular forces, and perhaps to nurture divisions and polarization within the opposition.

“There Is No Education”: Quality, Equity and the Secondary Stage

Mubarak declared education to be Egypt’s “national project,” and it was repeatedly listed as a reform priority, especially from the 1990s onward. However, reduced social spending had devastating consequences on quality and equity in the system, especially given its steady expansion. Many people I spoke to had a very concise and straightforward way of expressing this deterioration. It was sometimes enough to say that I was doing research on education to receive the response, “What education? There is no education” (mafish ta‘lim). I heard the phrase “there is no education” (mafish ta‘lim) countless times throughout my research. It was used to refer to the state of education as a whole as much as it was used by teachers, administrators and students to reflect on their specific conditions across different types of schools. What, then, does “no education” mean, and how do its connotations differ in different parts of the system?

Before discussing the quality of education, a brief description of the structure of the system is necessary. The preuniversity education system in Egypt is very large. In the late Mubarak era, it catered to about 17 million students and had over 1.5 million employees. It consists of a primary, preparatory and secondary stage. Under the constitution, the Basic Education stage, encompassing six years of Primary Education and three years of Preparatory Education, is free and compulsory for all children aged 6–14. Secondary Education comprises the two main general and technical tracks. Students who score below a certain annually determined cut-off score in the Basic Education completion exam can only continue in the technical secondary track focusing on vocational skills.Footnote 4 A smaller religious education or Azhar track enrolls about 10 percent of students across the different stages. Private schools were still a small part of the system, 7.4 percent of students being enrolled in private preuniversity education in 2006 (MOE 2007).

Private schools remain a small part of the system, but their importance lies in schooling the intellectual, economic and political elite, especially in language schools and international schools.Footnote 5 Private schooling started growing in the 1980s, with different rates of acceleration. Between 2001 and 2006 alone, the proportions of private classrooms at primary level increased by 31 percent, while the numbers of pupils increased by 24 percent (MOE 2007, Annexes, 48). Most private schools follow the national curriculum and are monitored by MOE inspectors. Private Islamic schools infuse this curriculum with additional religious content and activities. More than half of private schools are Arabic-language schools, while those targeting the upper-income brackets mostly provide instruction in a foreign language, usually English. Most private language schools follow the national system, although a growing number teach international programs like the British IGCSE and the American Diploma. As detailed in Chapter 2, privatization happens in large part informally through private tutoring and affects students across income brackets. It has done little, however, to remedy the decline in quality in the system.

The poor quality of learning in the system has resulted in a crisis of illiteracy among students as evidenced in Egypt’s ranking as second to last in the world in the 2016 international reading assessment PIRLS. Signs of poor quality had been emerging since the late Mubarak era. The results of a 2010 national standardized examination in Arabic, science and mathematics showed that average student scores were less than 50 percent, with large variations within the system (MOE 2010, 2014, 41). In the 2007 TIMSS international ranking, 53 percent of Egyptian eighth grade students (often chosen from the best schools) did not satisfy the low international benchmark in mathematics and 45 percent were also below the lower benchmark in science (UNICEF 2015, 39). This was already 5 percent lower than Egypt’s 2003 rank (see MOE 2007, 46, MOE 2014). The decline in quality is caused in large part by poor financing of an expanding system, and especially by the low teacher salaries it entails. Public spending on education in Egypt is low by international and regional standards and has been declining since 2000 (UNESCO 2009, OECD 2015). It is mostly absorbed by wages and recurrent expenditure. It is also skewed toward university education at the expense of primary and basic education and very poorly targeted at quality improvement (for detailed discussions, see Assaad Reference Assaad2010, AFA 2014, MOE 2014, World Bank 2013, MOE 2007, IBRD and World Bank Reference Youdell2005). Public investment in education is not only low but also distributed in a way that disadvantages the lower grades, which are critical for developing a learning base, and the poor, especially outside urban centers. The ratio of spending per student in higher education relative to preuniversity education averaged 3.2 in the same period in Egypt, as compared to only 1.1 in OECD countries (Assaad Reference Assaad2010, 3).Footnote 6 Although wages take up most of educational expenditure, teachers’ salaries are very low by regional and international standards.

I can work and satisfy my conscience as much as the money the ministry gives me. I get 2.5 EGP per class. If a supervisor comes in, here is my work written on the board. Hijri date [Islamic calendar] for 50 piaster, Miladi [A.D.] date for 50 piaster, the title of the lesson for 50 piaster, and the lesson prepared in my notebook for 50 piaster. So I owe you 50 piaster worth of explanation. What do you think I will tell you for 50 piaster?

The evolution of teachers’ pay in recent decades is critical to understanding issues of quality and equity and modes of privatization in the system. Rigorous tracking of the change over time in teachers’ wages does not exist. However, like other government employees’ salaries, teachers’ salaries have fallen substantially in real terms since the 1980s. By 1996, the starting base salary for teachers was 100 EGP per month, at which time about 900 EGP were needed to provide a decent living for an average Egyptian family (World Bank 1996, Annex 2, 1). Calls for increases in teachers’ salaries eventually culminated in the institution of the Teachers Cadre in 2006. The Cadre effectively represented a 30 percent increase in the salaries of teachers. However, a beginner teacher still received a salary of around 500 EGP per month, whereas only an income of around 1,200 EGP could put a family of four above the internationally recognized poverty line of 2 USD per day.Footnote 7 Furthermore, many teachers in Egypt were simply not hired on the Cadre, but on other types of contracts where pay ranged from 25 to 70 percent of a beginner’s Cadre salary.Footnote 8 The average annual teacher salary in 2009–10 was EGP 17,912, i.e. about 1,500 EGP per month (MOE, 2010, 172). This corresponded to 271 USD or $1,022 PPP per month.Footnote 9 Salaries increased after the uprising but their value quickly declined in real terms, following a devaluation of the pound and further austerity measures since 2016 (Chapter 7).

Teachers are generally dissatisfied with their pay, lack of decision-making power and autonomy, school allocations and working conditions (see Abdou Reference Abdou2012). The poor conditions of teachers begin within faculties of education. Admission to faculties of education is managed centrally and based on general secondary final grades, as with all university admissions. The minimum score requirements for admission are, however, not among the highest, and many students who enter educational faculties do so because they have not scored high enough grades for other faculties, and not necessarily because of a desire to become a teacher. Within faculties of education, many students complain that they are assigned to programs for which they had not applied, in which they have little or no interest, and for which they are not suited. Faculties of education suffer from overcrowding, limited possibilities for small workshops or seminars, very limited school-based practice and overall conditions that lead to weak professional preparation. In-service professional development also suffers from a host of weaknesses and is seen as having limited impact on teacher performance (see OECD 2015, Ch 5). The image of teachers as low-paid, low-skilled and inexperienced persists (UNEVOC, 2013). This is especially so for technical track teachers and trainers, whose status and career prospects are considered lower than those of general education teachers (ETF and World Bank, 2005a). Teachers in public schools are part of the Egyptian civil service, and the teaching workforce is one of the few sectors in which women enjoy proportionate representation.Footnote 10

Tracking and Quality in the Secondary Stage

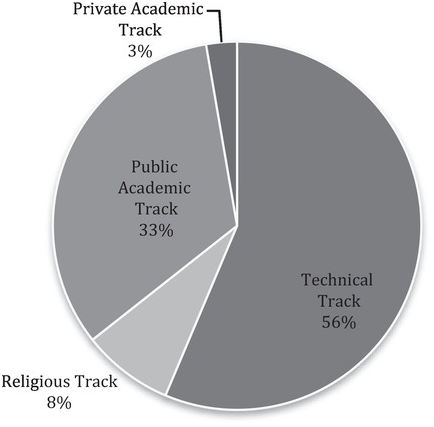

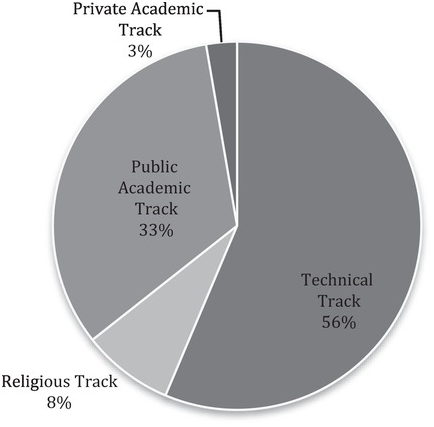

As the research focuses on secondary education, a more detailed picture of this educational stage is essential. Between one-quarter and one-fifth of youth in this age cohort are not enrolled in any track of secondary schooling.Footnote 11 Of those enrolled in secondary education in 2005–6, 56.3 percent studied in technical schools, 32.9 percent went to public general secondary schools, 2.7 percent were enrolled in private general secondary schools, and 8 percent were attending religious Azhar schools (MOE 2007, Annex 2, 77). Recalculating the ratios taking into account MOE schools only (excluding Azhar enrollment), about 61 percent of students were enrolled in technical schools, 36 percent in general schools and 3 percent in private general schools.Footnote 12 General secondary education is a three-year track, where students can select to focus on arts or science subjects and from which successful students can go on to study at university level. The majority of technical schools are three-year technical secondary schools leading to a formal qualification (diblum) as a Technician. Students in the technical schools enroll in three main specializations – industrial, commercial and agricultural – from which they can seek formal employment or go on to attend two-year institutes.Footnote 13 Students are allocated to specializations based on their scores, regardless of preferences or aptitudes. In 2007, students enrolled in industrial specializations accounted for 50.6 percent of all students enrolled in technical education, while commercial and agricultural specializations accounted for 38 percent and 11.4 percent, respectively (MOE 2007, Annexes, 104). There is a general tendency for male students to be tracked into industrial specializations, while female students are directed into commercial schools. Overall, less than half of all students who enroll at the secondary stage gain access to higher education, where the vast majority attend universities and 6.7 percent attend lower status technical institutes (Megahed and Ginsburg Reference Megahed, Ginsburg, Holsinger and Jacob2008). The vast majority of general secondary students (94 percent) go on to higher education (76 percent to universities and 18 percent to two- and four-year institutes), but only 9 percent of technical secondary students were able to do the same (Assaad Reference Assaad2010, 6).

Technical education, in which about half of all students are enrolled, is widely seen as offering almost no educational value. A common statement repeated by teachers was that a technical school qualification is “‘no more than a certificate of literacy’.” Although it has become increasingly apparent in recent years that technical education was superfluous and no longer served any need (Elgeziri Reference Elgeziri2010), the government continued to steer students toward it merely to limit demand on general secondary education and universities and to serve as the government’s safety valve for young men and women from poor socioeconomic backgrounds (Antoninis Reference Antoninis2001, Gill and Heyneman Reference Gill, Heyneman, Gill, Fluitman and Dar2000). In addition to its chronic problems of outdated curricula and poorly trained and paid teachers, most schools lack the basic equipment and maintenance required for teaching those outdated programs (ETF and World Bank 2005b).Footnote 14 Even official MOE analysis has articulated technical education as inadequate for meeting the needs of society or of local and international labor markets (MOE 2007, 278). Although the quality of education in general secondary is much higher, there are still serious concerns about teaching and assessment methods, rising costs in terms of private tutoring, and low returns in terms of high unemployment among graduates (see MOE 2007, 278). Despite the problems of the general secondary or thanawiya amma exam, it is used to decide the academic and productive lives of millions of Egyptians, and it has had a markedly negative influence on the educational system as a whole, leading it in the direction of increasingly arbitrary university admissions and placement policies, and magnifying an already existing culture of teaching and tutoring to the exam (OECD 2015, 164). Poor quality in the secondary stage stems from the poor quality of teaching the bulk of basic education schools, which create a weak knowledge base that becomes very difficult to remedy in the higher grades.

With some exceptions, teaching in Egyptian schools is characterized by teacher-centered instruction, rote memorization, little or no emphasis on the development of critical thinking skills, a tendency to overemphasize esoteric details and unimportant distinctions, to pay insufficient attention to core concepts and ideas, and too little connection of learning to real life and contemporary circumstances (see, for example, OECD 2015). However, the problems of the system go beyond memorization or the quality of curricula. The deterioration of learning outcomes over the previous decades has not corresponded with changes in pedagogy or a turn toward memorization. In fact, the focus on memorization and exam performance is not merely a pedagogical choice that can and should be reformed by educational authorities: It is critically reinforced by poor resources, the accumulation of poor learning in earlier grades, weak teacher preparation and low trust in the system. If teachers are not sufficiently trained to teach a certain subject, and if students have hardly been able to learn the basics of that subject, memorization can be the only way to pass students from one stage to another. If workshops in technical schools have no functioning equipment, or if equipment is locked away out of a fear that the school authorities would be held accountable for any damage resulting from its use, there are few options apart from memorizing a few points for the exam.Footnote 15

To give a concrete example, on one of the rare occasions when I observed a supervisor inside a classroom, he rebuked, interrupted and directed in an authoritarian manner the English teacher giving the class in the girls’ general public school. The teacher, however, had simply not received the training to apply the participatory methods advocated by the supervisor, who had briefly received training outside Egypt. In fact, he had very weak knowledge of English in the first place. He himself had graduated from university with poor subject knowledge. Furthermore, his students, who had been through several years of poor English instruction, did not really have the ability to deal with the curriculum at hand and therefore relied on what they could memorize by repeating after him. They needed to focus on what exam questions require, so that they could better target their memorization efforts. In fact, they voiced support for the teacher’s memorization-focused approach over the more interactive methods desired by the supervisor. As one student strikingly put it, “the [English] teacher’s goal is not to teach us the language. He teaches us what we need for the exam.” In turn, exam question and exam preparation guides are geared to these skills levels and reward memorization, not participation or communication skills on the part of students. Rote learning is in fact what happens in the best of classes when the teacher actually enters the classroom and teaches the material. If conducted at all, each class presents students with small bits of data and bullet points to memorize, often presented with little contextualization or connection to applied usage or other material and tasks. The meanings of mafish ta‘lim become clearer and more disturbing when examining the interaction of privatization, poor resources, absenteeism and permissive assessment, as explained in Chapter 2.

These conditions have led to increasing inequality and diminishing returns to education. Education has been substantially devalued in the face of a rapidly increasing supply of educated individuals and limited expansion in the demand for educated labor (Salehi-Isfahani, Tunali and Assaad Reference Salehi-Isfahani and Assaad2009). As Assaad and Krafft (Reference Assaad and Krafft2014, 11) show, young people’s struggles with secondary education or higher to make a successful modern transition is a relatively new phenomenon in Egypt. High and unequal levels of household expenditure in private tutoring and tracking into vocational and general secondary schools that depend on high-stakes examinations substantially contribute to unequal learning outcomes (Ersado and Gignoux Reference Ersado and Gignoux2014, World Bank 2012).Footnote 16 Official achievement data in Egypt show the polarization based on social class and/or financial ability (see UNDP Reference Sobhy2010, 44). Furthermore, inequalities in learning opportunities among young Egyptians are high compared to other countries in absolute levels, and learning gaps appear in early grades (Ersado and Gignoux Reference Ersado and Gignoux2014).

This state of affairs has generated significant protest in the education sector. Teachers, administrative staff, students and parents have engaged in various protest activities relating to educational issues. Teachers have resorted to techniques similar to those used in the wider protest movement, from demonstrations to hunger strikes and litigation. Successful litigation included technical education teachers suing for inclusion in the Teachers Cadre. Other categories of teachers and administrators have since successfully fought for the legal right to be included in the Cadre, periodically staging protests in front of the ministry in Cairo. Some of the most widely covered protests by students and parents occurred immediately before the uprising in semiprivate schools in December 2010 and January 2011 and were met with police intervention and intimidation (as discussed in the Conclusion chapter). Apart from these issues around the quality and equity of education, the ideological content of textbooks and everyday features of schools also underwent significant transformations from the early postcolonial era to the present.

Nationalism and Citizenship in Textbooks and Everyday School Relations

Throughout Egypt’s modern history, the education system has been an arena for struggles around national identity, citizenship and the ideologies that inform them. This is not only reflected in official textbook narratives but also in who becomes a teacher, what kinds of narratives can be voiced in school rituals and everyday discourses and the purpose of schools as disciplinary institutions. The Nasser regime (1952–70) treated state schools as central to establishing and maintaining the new postindependence revolutionary political order. It consolidated the role of schools through massively expanding access to education and by attaching considerable importance to school curricula as primary means of disseminating the values, symbols and goals of the July 1952 Revolution. History and National Education textbooks under Nasser underwent a slow and uneven process of change to reflect the new ideologies and directions (Makar and Abdou Reference Makar and Abdou2021, Adli Reference Adli and Ayoub2007). As Arab nationalism and state socialism became the key ideological drivers of the Nasser regime, they gradually became the bases upon which national belonging and citizenship were articulated in Nasserite textbooks.

Starting in 1959, with the greater emphasis on Arab socialism, the education system was tasked with preparing the child for life in “a cooperative democratic, socialist, society” (Adli Reference Adli and Ayoub2007, Starrett Reference Starrett1998). Textbooks emphasized questions of poverty and exploitation and the expanding social and economic citizenship rights promoted by the regime. Nasser-era textbooks placed great emphasis on class struggle and the struggle against imperialism and framed these as the bases of regime legitimacy (Adli Reference Adli2001). These were also articulated as part of the core of Egyptian identity, where not only “struggle” but also “revolution” were identified as common threads running through Egyptian history and national identity. Critically, textbooks gave considerable centrality and agency to “the people” (al-sha‘b, a word that rarely appears in contemporary textbooks) and other oppressed peoples across the world. The textbooks were full of passages about the role of resistance and national liberation movements and revolutions, with special emphasis given to the struggles of peoples and the role of youth in promoting and defending the values and goals of the Revolution (Adli Reference Adli2001). A measure of ownership of these discourses on the role of “the people” was evident among different segments of Egyptians and was reflected in expressions of their own sense of agency and contribution to the Revolution (Mossallam Reference Mossallam2012). Educational discourse also went to considerable lengths to introduce notions of gender equality and emphasize the role of women in building the country. Finally, textbooks also emphasized democracy as a basic principle of the new regime, an assertion that was purely rhetorical, although participation in state-affiliated organizations such as the Socialist Union was encouraged and rewarded.

The centrality of the July Revolution and its declared principles of social justice, anti-imperialism and Arab nationalism were progressively undermined in textbooks under Sadat and entirely removed and revised under Mubarak. The regime sought to promote the new personal vision of Egypt and Egyptian identity of Sadat (who ruled 1970–81), where three key areas represented new developments in Egyptian educational discourse. These were the focus on “science and faith” as the basis of Egypt’s progress and desired identity, the beginning of the involvement of international agencies in educational policy-making, and the initiation of experimental schools (a privatization measure whereby higher quality elite public schools charged fees and accepted high-performing students), in addition to a focus on his own personality cult. As Adli (Reference Adli and Ayoub2007) notes, the 1977 History textbook was full of Sadat’s photographs, with the greatest importance being placed on individual leadership: Little attention was given to the role of the people, or even to the new political parties that were allowed to form.

Educational goals in the Sadat era also began to emphasize the link between education and employment, adjustment to the open-door policy, and the expansion of technical education to absorb 60 percent of secondary students. In contrast to the politicization and emphasis on “participation” in Nasserite discourses, a number of themes shaped Sadat’s educational agenda, including the declaration that there was to be “no politics in education” (in textbooks or in university activism), the emphasis on the “moralities of the village,” the importance of tradition and respect for “values,” obedience and deference to elders, and the emphasis on faith and religion (for more detailed discussions, see Adli Reference Adli2001, Brand Reference Brand2014). Beyond curricula, the Sadat regime enabled Islamist groups to gain control over universities and university politics and Teacher Colleges, with a strong base in Upper Egypt, especially Assiut University (Adli Reference Adli2001, Khalil Reference Khalil2009). Islamist control over Teacher Colleges has arguably had a profound impact on education until the present day (Chapter 6). Repressed under Nasser, the Islamist forces that gained influence under Sadat and Mubarak had more reason to gradually erase his legacy from the textbooks and replace it with their own.

Mubarak continued most of the trends initiated by Sadat by allowing greater Islamist influence on education, by distancing his regime from the values and rhetoric of the July Revolution, and through the general “depoliticization” of educational discourse and the greater involvement of international agencies in educational policy-making. Discourses on Israel were one aspect of the erasure of the tropes of Arab nationalism from textbooks that became particularly controversial under Mubarak. While global and specifically US pressures relating to curriculum development and the promotion of religious tolerance are frequently highlighted, all other areas of educational policy were heavily affected by foreign technical assistance and neoliberal agendas, particularly in terms of greater privatization and lower educational spending. Studies of Mubarak-era school curricula argue that schools prepare the young to accept that the movement of society is not determined by masses but by individuals so that society’s overcoming of problems and crises depends on the existence of the ruler (the manager, the hero, the rescuer, the savior), while the child is raised to equate the government with the state and country and to take the side of political authority, depend on it, trust it and adopt positive attitudes toward it (Abdul Hamid Reference Abdul Hamid2000, 124). Textbooks primarily tackle the history of state authority and ignore the people’s history, and fail to mention the flaws of different rulers or their relationships with different classes, as well as refraining from the treatment of any controversial issues (MARED 2010). Contemporary textbooks ignore European, American or Asian history, as well as the histories of other colonized people, in order to focus only on the injured self (unique in its injury as it was unique in its historic greatness), with constant expressions of pride in the self and parallel condemnations of others (MARED 2010). Textbooks also increasingly highlighted large portraits of Mubarak and First Lady Suzanne Mubarak, with smaller photographs for other leaders. Research on History textbooks has also emphasized their factual mistakes. In sum, History textbooks aim to create uncritical citizens who are expected to learn and memorize the one and only master narrative or the history of the nation (e.g. Atallah and Makar Reference Attalah and Makar2014, Fikry Reference Fikry2015). Egyptian textbooks are of course no exception in this regard. Since “[n]ations rarely tell the truth about themselves,” it is not surprising “that the history which is taught to children is often a watered-down, partial and sometimes distorted, sometimes fictional, view of a national past based upon cultural, ideological and political selection” (Crawford Reference Crawford2004, 10–11).

The Securitization and Islamization of Schools

The Mubarak regime’s accommodation with Islamists extended the Sadat- era trends of enabling the recruitment of Islamists on university campuses, in schools and as social workers, putting them in direct contact with the public, especially in Upper Egypt (Roussillon Reference Roussillon and Daly1998, 387). This was combined with the influence of tens of thousands of teachers returning from work assignments in the Gulf and bringing more conservative ideas back into Egyptian classroom. Early-childhoods education was also left to community associations, which are run by religious entities in most parts of the country outside of affluent urban centers.

The outcome has been a pervasive Islamization of schools that is reflected in almost every facet of their appearance and activities. This includes Quran recitation and memorization contests being at the forefront of school activities, daily school radio programs that are saturated with religious content, Islamic prayers and chants replacing or succeeding nationalist rituals in morning assemblies, school celebrations centered on Islamic occasions and teachers pressuring unveiled students and teachers to wear the hijab (see Herrera and Torres Reference Herrera and Torres2006, MARED 2010). Girls were increasingly excluded from sports on both religious and cultural grounds, and musical and other artistic activities began to disappear from schools. The morning assembly has been particularly used across Egypt’s schools to increase the amount of religious content by altering or replacing saluting the national flag with more Islamic chants (see Herrera Reference Herrera, Herrera and Torres2006, Saad Reference Saad, Herrera and Torres2006, Starrett Reference Starrett1998). The morning assembly (tabur) is therefore a key arena for the contestation of official narratives and is a ritual to which this research pays special attention (Chapters 6 and 7).

Schools are highly securitized and surveilled spaces, not only in terms of who can gain influence on them and what discourses can be voiced inside them, but also in terms of strict limitations on even entering schools, on civil society associations being able to work on school improvement and even stricter limitations on media reporting and conducting research inside schools. Education is often articulated “as a matter of national security” in official statements (Sayed Reference Sayed2006). This terminology gained special currency after the wave of terrorist attacks in the 1990s and the confrontations between the state and Islamist groups. It therefore centers heavily on the shifting relationship with Islamist forces. After the wave of terrorist attacks in the early 1990s, the state took measures to undermine Islamist groups, including loosening their hold on educational institutions (Sayed Reference Sayed2006, 34). The 1990s especially saw thousands of teachers transferred to nonteaching jobs or remote locations on security grounds (Bahaa Al-Din Reference Bahaa Al-Din2004). However, these measures did not undermine the overall trend toward growing Islamization.

Beyond Islamism, oppositional discourses and political expression and organization more generally face severe limitations in schools. As highly securitized spaces, schools are closely monitored to ensure that all school discourses – including every teacher’s exam questions and every student’s answers – are devoid of oppositional themes, especially under the banner of combatting extremism and terrorism. Political Communication representatives in every educational district reportedly monitor teachers and receive any reports about oppositional discourses in classrooms. In addition, state security officers responsible for the educational file in each district or governorate quickly become involved if there is any sign of collective action in schools. Educational officials and state security personnel therefore retain tight control over political and religious expression in schools, although the scope, effectiveness, consistency and actual purpose of this control are all debatable.

The Research and Its Limitations

This book has been made possible because I was able to obtain an official permit to conduct extended research inside Egyptian schools. Obtaining an official research permit was already exceptional at the time, but research access has become even more difficult given growing research restrictions since 2014. I elaborate here on some of the issues involved in conducting research in this context, how I went about the research, how I chose the research schools and the likely implications of these choices.

My aim was to study mainstream schools catering to different social strata and genders under the national education system. I chose to focus on the secondary stage (Grades 10–12) in order to examine the more elaborate nationalist and citizenship discourses targeted at older students and to be able to engage more meaningfully with young people about the relevant conceptions and performativities across different social strata reflected in the more explicit tracking in the system at this stage. The focus on these mainstream schools excludes the religious Azhar schools, which represented less than 10 percent of the system and can be seen as being similar in terms of socioeconomic profile to public general secondary, and the international schools that make up less than 0.5 percent of schools and student enrollment.Footnote 17 My focus was on schools in the largest part of the system: technical schools in which about 60 percent of secondary students were enrolled in 2006, and general secondary schools that accounted for about 25 percent of students (MOE 2007, Annex 2, 77). Private schools enroll fewer than 5 percent of secondary school students, but they represent the politically and socially influential educated classes (see Figure 1.1). From among these private schools, I chose to study the more privileged English language schools. Foreign language private schools enroll about half of private schools students and represent the category most familiar to the Egyptian intelligentsia. The official general/academic (thanawiya amma) curriculum is implemented in these schools, but mathematics and science are taught in English and students receive additional instruction in Advanced Level English, whose curriculum is centrally decreed by MOE. Guided by these criteria, I studied schools in different neighborhoods of Greater Cairo, where I was able to gain access through existing contacts.

I conducted most of the pre-2011 fieldwork from 2008 to 2010. I combined immersive site-specific fieldwork in the six research schools (two technical schools, two general schools and two private schools) with numerous individual interviews and discussions with teachers, students and school staff from different schools across the city and at different educational stages. In terms of gender, I selected one boys’ school and one girls’ school in each category of public schools (technical and general). However, upper-range private boys-only schools are not common, as most boys enroll in mixed schools. Therefore, for private schools, I conducted fieldwork in one mixed school and one girls-only school. The six research schools are:

Public three-year technical secondary school for girls – commercial specialization;

Public three-year technical secondary school for boys – industrial specialization;

Public general/academic secondary school for girls;

Public general/academic secondary school for boys;

Private English language school for girls;

Private English language school for boys and girls.Footnote 18

Throughout the text, I refer to the public technical track schools as the technical schools, to the public general (academic track) schools as the general schools, and to the private general (academic track) schools as the private schools. I sometimes refer to school administrators and teachers as a whole simply as “teachers” or “school authorities,” but distinguish between administrators, social workers and teachers when this is relevant for the analysis. In order to protect respondents from harm or embarrassment, I have not used their real names, nor those of the schools. I have also not given the name of the neighborhood where the public schools were located, as this may make it easy to deduce to which secondary schools, principals and sometimes teachers reference is being made.

In terms of classroom observation, I spent the school day inside different classrooms in each school for an average of two days per week over a period of one semester for each school, totaling about 480 hours spent in the schools altogether. In each of the six research schools, in addition to classroom observations and open-ended discussions, I conducted semi-structured group and individual interviews with teachers, students and the school principal, and sometimes other administrative staff as well (totaling 149 interviewees: 6 school principals, 34 teachers and 109 students). I also collected other materials that were made available to me and took numerous photos in all of the schools. I asked students, teachers and principals, individually and collectively, about three key themes: informal privatization in the form of private tutoring, forms of control and punishment by teachers and constructions citizenship in terms belonging to the nation as well as how they would describe ‘students as a whole’ or ‘this generation’. Although I asked students to reflect on “love” of and “feelings of belonging to the country,”Footnote 19 I did not employ the sociology or anthropology of emotions as a tool of analysis (Abu Lughod and Lutz Reference Abu-Lughod, Lutz, Lutz and Abu-Lughod1990). I used the invocation of love of country as an opening to discuss constructions of national belonging and citizenship.

With an official school start age of 6 years, secondary school students are 15–17 years old and those who had repeated school years (more common among boys) were 18 or older in their final years. Most teachers were middle-aged, married, relatively experienced and hired on permanent contracts. This is not unrelated to the systematic bias toward secondary education (especially general secondary) and urban areas in the deployment of better-qualified and experienced teachers hired under the permanent contracts of the official Teachers Cadre system (see MOE 2014). The research reflects a healthy gender balance due to the selection of schools and because the teaching and administrative staff in all schools always included both men and women.

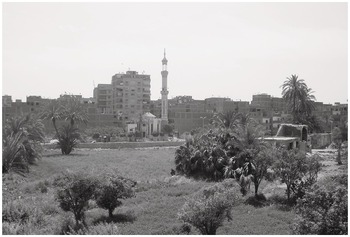

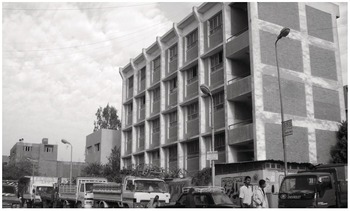

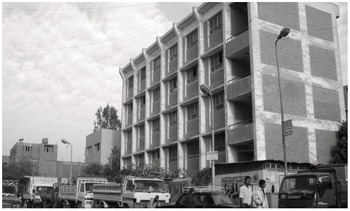

The four public schools are located in the same lower-income informal neighborhood in the east of Cairo, and the private schools are in two different affluent neighborhoods. Although they are located in an informal neighborhood, the four public schools have been the targets of significant upgrading efforts by nongovernmental bodies. In fact, the two general schools are newly built schools, through funding provided by an international development agency (Figure 1.3), while the technical schools are older buildings (see Figures 1.4 and 2.1). While the educational district is considered underperforming by school actors, it is not one of the worst performing districts in the city or one with the highest classroom densities. Importantly, to categorize the neighborhood where the four public schools are located as informal does not imply that it is necessarily poor. Despite the fact that most residents may be working class and/or working primarily in the informal economy, there is still a clear professional class presence in the neighborhood. Also, in terms of its occupational composition, geographical features, perceptions and crime profile, this informal neighborhood is not simply like any other informal neighborhood in Cairo. It is not known for extreme poverty, tin houses, high crime rates or the drugs trade. It occupies a peripheral position and has strong rural roots (being composed or surrounded by agricultural land until recent years). Although its main streets are crowded and bustling, the surrounding green fields give it a generally mellow vibe (Figure 1.2). Like many urban neighborhoods, it has a healthy minority of Christian residents. There is also a marked Muslim Brotherhood influence in the neighborhood, which became more visible after the Revolution in electoral campaigning and results. The two neighborhoods where the private girls’ school and the mixed school are located, Nasr City and Zamalek, are quite different in composition and features. However, the two schools cater to very similar clienteles within the two neighborhoods and have similar reputations in terms of being considered good private schools that do not charge very expensive fees (about 6,000 EGP per year in 2009 prices). Both schools also offered more expensive programs in international tracks, demonstrating the multiple tracking within both the public and private systems.

This study focuses on the educated classes concentrated in urban areas. About half of Egyptians (45 percent) live in urban areas. The capital, Cairo, is massive, with close to one-fifth of the country’s population or 17.2 million residents in 2017 (CAPMAS 2017), and diverse enough to display a range of urban and peri-urban phenomena. While rural education remains grossly understudied in Egypt, existing research (Tawfik Reference Tawfik2019) suggests that rural schools share key features of the trends in the less-advantaged technical education track described here. The students in the research schools mostly belong to the top three or four wealth quintiles.Footnote 20 The research therefore does not directly address the experience of youth in the bottom one or two quintiles. Secondary schooling, and especially general secondary, is a largely urban phenomenon, and one in which children from disadvantaged families are far less likely to enroll (MOE 2007, UNDP 2010). I refer to technical students as belonging to the working classes, general school students to the middle classes and private school students to the affluent classes. Private language school students belong to the highest socioeconomic brackets of the most affluent 3–5 percent, especially that these are foreign language private schools, which enroll less than 5 percent of students.Footnote 21 General school students clearly also belong in the top wealth quintile but occupy a wide range, including much of the second quintile. Technical school students may not belong to the poorest quintile, but they typically do not continue on to university nor take part in the traditional middle-class professions, and most likely they would not classify themselves as such. Certainly, even in one school, social class is never uniform, and this research does not attempt to pin down the class location of students by mapping out constellations of economic, social and cultural capital, in Bourdieu’s (Reference Apple and Weis1986) sense, or the socially embedded practices that are constitutive of class locations and productive of distinction. Importantly however, there is a vast socioeconomic differential across the three tiers of schools, which is especially evident in household spending on education. As I describe in Chapter 2, private expenditure on education per student in the private language schools was 3 times that in public general schools, and up to 30 times the expenditure in the technical schools, whereas private spending in the general schools is could reach 10 times that in the technical schools.

A number of aspects surrounding my insertion into the schools arguably influenced my findings and the patterns I was able to observe. This includes the overall learning conditions, and issues around nationality, social class, gender, religious identity and self-censorship. The quality of the time I spent in schools and my rapport with students were shaped by the realities of “no education.” As many teachers simply did not show up to class, attention in the classroom was often turned to me, and the “observation” turned into a group discussion. After many classes, in the class time of the subsequent class, there was ample time to engage with students about what had happened, as well as discussing other contextual issues about the school and their experiences, creating greater familiarity and allowing for bonds to form more rapidly with students. My attempt at classroom “observation” was therefore frequently futile and rather unusual by the standards of the anthropology of education. This is why I refer to my fieldwork as research in and on schools as much as with young people.

Being in the schools with an official permit had contradictory implications: It conferred legitimacy and assuaged the typical security fears that relate to foreign researchers. However, even as an Egyptian native, as someone studying in the West, I was faced with a common concern about “tarnishing the image of Egypt abroad.” Furthermore, because such research permits are not common, a perception sometimes developed among administrators that I had some supervision or inspection role for the Ministry of Education. This meant that administrators granted me easy access and teachers felt more pressured to improve their performance in my presence. So despite the negative patterns I report, I was likely not exposed to the darkest realities of the schools. Because I did not wear a hijab, I was consistently probed about my religious identity through direct questions about my full name. Since respondents seemed to place significant importance on this issue, my clearly Muslim full name arguably facilitated my access and how most respondents engaged with me, while arguably limiting the openness of Christian students in discussing various relevant issues. One limitation of the research therefore is that it does not directly address the experiences of Coptic students and other minorities, nor of students who would not openly express opinions considered controversial by others. It says little about how Coptic students experience the Islamization of schools, their overall de facto access to citizenship rights, and any oppositional discourses on the state that may relate to their status as Christian citizens. Muslim students might have also reflected on other themes if they had deduced from my demeanor or discourse that I had Islamist leanings.Footnote 22 Finally, being a woman arguably facilitated my access, as both girls and boys seemed at ease in speaking and sharing with me.

Another limitation that is worth noting is the potential impact of self-censorship and fear of repression. Discussions of political issues are simply not allowed in schools (see also Abdul Hamid Reference Abdul Hamid2000). This meant that I was not able to raise overtly political issues, neither in my research permit request nor in my discussions with those students, and was concerned about encouraging students or teachers to cross any red line. Censorship and self-censorship were prominent and often occurred visibly when students would silence each other through words or gestures, and teachers would correct other teachers or ask them to refer to “officials,” not the president and the ministers by name, or when I would jokingly tell students when they criticized the president or the regime, “Do you want them to take away my permit or what?” However, I gradually took my cue from students, and many teachers, who felt at liberty to make oppositional comments. My findings therefore reflect the competing forces of self-censorship, increased indignation and perceived liberty to express opposition in the late Mubarak era.

My findings, based on these urban Cairene schools, do not reflect the full extent of Islamization across Egypt’s schools or the Islamist sympathies among its young. Students might have also self-censored expressions of politicized Islamist identification for fear of repression. However, the deployment of Islamist discourses among students (Chapter 6) arguably reflects the selected profile of urban educated youth without too much self-censorship. The relatively free post-2011 elections results, for example, show that although Islamists typically secured significant support in similar urban districts, they received far stronger support in other parts of the country (see, for example, Martini and Worman Reference Martini and Worman2013).

To explore post-2011 trends (Chapter 7), I undertook further intensive fieldwork from March to August 2016, conducted expert interviews in the summer of 2017 and rounds of follow-up interviews in 2018. The research was not longitudinal in the sense of following up with the same students or with teachers in the same schools, and I did not seek a new research permit to conduct observations inside schools. The 2016 qualitative fieldwork consisted of group and individual interviews with over 40 students and teachers from 12 different technical, general and private schools in Greater Cairo. The public schools (technical and general) all had a similar profile to the research schools and were located in comparable neighborhoods (Mit Uqba, Hilwan, Al-Marg, Shubra al-Khayma and Sayida Zaynab) and the private school students and teachers were from privileged English language schools. Apart from the main research themes (privatization, discipline and belonging), I asked about the most important changes since 2011, referencing recent initiatives and official statements. In the summer of 2017, I conducted further interviews on the key themes with experts and stakeholders, including researchers, members of textbook committees, journalists, teacher syndicate leaders and practitioners in NGOs and donor agencies. The interviews revisited the key themes of private tutoring, discipline, punishment and nationalist discourses, mapping them against new policies, reporting and analysis. In 2018, I conducted 10 follow-up interviews with students and teachers, focusing especially on the new reforms that were being introduced.

Sampling the Textbooks for Discourses of Citizenship and Belonging

In addition to the ethnographic study and interviews, I conducted a detailed analysis of the official textbooks for the three years of secondary education in all tracks and specializations. I gave equal attention to the technical education textbooks, which have been mostly ignored in previous research. While building on the available studies relating to different educational stages and historical eras, the research focuses on textbooks in the critical period of around 2011. It draws particularly on examples of the 2009–10 secondary school textbooks, which were taught during my fieldwork in the schools. Egyptian textbooks and their authorship committees generally undergo very limited changes from year to year (Attalah and Makar Reference Attalah and Makar2014, Starrett Reference Starrett1998). Most of the textbooks had been in use with limited changes from the 2000s to the late 2010s. These 2009 textbooks in fact continued to be used up to the 2014–15 academic year, with limited changes. I reviewed the relevant textbooks for the subsequent years until 2019–20 and the related news reporting and official statements about textbook changes, and I describe key subsequent changes in Chapter 7.

The main textbooks analyzed are referred to by the indicated acronyms or titles. National Education textbooks start with NE, Arabic language textbooks with AL.Footnote 23 Exact quotes are obtained from the following versions.

Arabic Language for First Secondary 2019–2020;

History for Third Secondary (Literature Specializations) 2016–2017;

Ana al-Masri National Education for First Secondary 2016–2017;

National Education for Third Secondary 2015–2016;

National Education for Third Secondary 2019–2020;

NEFST: National Education for First Secondary Technical Education for Commercial, Tourism, Professional and Industrial Specializations 2009–2010;

NEFSG: National Education for First Secondary General 2009–2010;

NEGSC: National Education for the General Secondary Certificate 2009–2010;

ALSSG: Arabic Language for Second Secondary General 2009–2010;

Wa Islamah: Arabic Language Novel for the General Secondary Certificate 2009–2010;

ALTSTCH: Arabic Language for Third Secondary Technical for Commercial and Hospitality Specializations 2009–2010;

ALTSTIAS: Arabic Language for Third Secondary Technical for Industrial and Agricultural Specializations 2009–2010;

HGSC: History for the General Secondary Certificate 2009–2010.

In addition, I also consulted a number of the corresponding external textbooks and study guides for each subject, as these are the textbooks the students actually use, in addition to their tutoring notes. I used the two most popular external textbook series, Al-Adwa’ and al-Mu‘alim.

In addition to observations, interviews and textbook analysis, I have surveyed a large volume of relevant policy documents, local and international reports, press coverage and social media content, which are weaved into the analysis across the chapters. Finally, apart from the research for this book, my work in the educational field in Egypt extends from 2004 to the present. It has involved interviews and collaboration in numerous rural and urban locations with teachers, administrators, parents and students, researchers, experts and educational officials from the highest level in the ministry to the smallest local level. It has encompassed a range of research, policy and project implementation and evaluation engagements in areas ranging from early childhood education to teacher professional development, school construction and the “new education system” launched in 2018. This wider exposure across educational stages, topics and regional contexts also informs the analysis and arguments of the book.