Arguments about the pros and cons and possible effectiveness of face masks during the Covid-19 crisis have occupied considerable space in specialist, medical venues such as peer-reviewed journals and science blogs, as well as public forums such as mainstream media and social media – the latter attracting contributions from medical specialists and lay members of the public alike. The debate has often been heated, and there have been reports of individuals resisting the stipulation to wear face masks in shops and on airplanes, at times leading to acts of physical violence. Drawing on the narrative paradigm, this chapter examines some of the arguments for and against face masks as articulated by a diverse range of individuals and constituencies within and beyond the Anglophone and European world, the justifications given in each case, and their underlying values and logics.

At the heart of the controversy surrounding the stipulation to wear face masks during the Covid-19 pandemic is an institutional narrative that has been characterized by conspicuous structural and material incoherence from the very start. The medical community and World Health Organization (WHO) both gave conflicting messages about the benefits and safety of using face masks throughout. In turn, as Austin Wright argues in the October 2020 issue of UChicago News, the uncertainty created by expert mixed messaging allowed politicians such as Donald Trump and their advocates ‘to create competing politicized narratives that weaken[ed] public compliance’ (Reference WrightA. Wright 2020). These competing narratives often appealed to nationalistic, misogynist and homophobic tropes that tend to resonate among sizeable sections of the population during periods of extreme insecurity, including wars and pandemics, when people feel the need to reaffirm threatened social identities. Disagreements among members of the medical community and weak or conflicting recommendations on the part of organizations such as WHO and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention thus created a space for the UK’s Boris Johnson, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro and other high-profile personalities to amplify values such as masculinity and personal liberty at the expense of public safety and social responsibility. We explore the extent to which the narrative paradigm can explain this trajectory, and further enrich it with the concepts of narrative accrual and identification where relevant to offer a more cogent account of some of the extreme responses to face masking that we have witnessed in the context of Covid-19.

3.1 Structural and Material (In)coherence in Expert Narratives

Conflicting messages about face masks issued by health authorities and members of the medical community, particularly during the early days of the pandemic, were informed by divergent understandings of the transmission route of the virus. There is general consensus among experts that virus transmission either occurs directly (between persons) or indirectly (through objects). Object contamination as well as contamination of persons at a short distance happen through large droplets while airborne transmission via aerosols can occur over an extended distance through the respiratory tract (Reference Zhang, Yixin, Zhang, Wang and MolinaZhang et al. 2020). With regards to public health measures, transmission through contact and droplets is typically controlled through physical distancing, hand washing, surface cleansing and wearing masks if people stand less than 6 feet apart, while the measures to control airborne diseases include ventilation and wearing face coverings when sharing air (Reference Czypionka, Greenhalgh, Bassler and BryantCzypionk et al. 2020). Nevertheless, advice issued by health authorities at different times has reflected structural incoherence in terms of both the recommendations and their theoretical underpinnings.

The WHO gradually moved towards recommending face masks in every situation, while the theory supporting the recommendations was only partly modified accordingly. In April 2020, the WHO’s advice was to reserve the use of masks for health personnel, arguing that ‘there is currently no evidence that wearing a mask (whether medical or other types) by healthy persons in the wider community setting, including universal community masking, can prevent them from infection with respiratory viruses, including COVID-19’ (WHO 2020a). The UK’s Chief Medical Officer, Jonathan Van Tam, reiterated the same message at a Downing Street Press Conference on 3 April (Reference SchofieldSchofield 2020):

I was on the phone this morning to a colleague in Hong Kong whose [sic] done the evidence review for the World Health Organisation on face masks.

We are of the same mind that there is no evidence that the general wearing of face masks by the public who are well affects the spread of the disease in our society.

Yes it is true that we do see very large amounts of mask-wearing in south-east Asia, but we have always seen that for many decades.

In terms of the hard evidence, we do not recommend face masks for general wearing for the public.

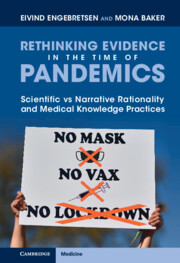

The WHO went on to even warn against the use of masks in community settings on the basis that it runs the risk of creating a false sense of security and poses a possible risk of self-contamination. It further argued that ‘the two main routes of transmission of the Covid-19 virus are respiratory droplets and contact’ and denounced the claim that Covid-19 is airborne as ‘misinformation’ and ‘incorrect’ (Figure 3.1).Footnote 1 On 5 June 2020, the organization updated its advice, this time encouraging the general public to wear masks in specific situations and settings where physical distancing could not be achieved. The main route to transmission was still considered to be droplets and contact. However, the guidelines also now acknowledged that ‘in specific circumstances and settings in which procedures that generate aerosols are performed, airborne transmission of the COVID-19 virus may be possible’ but that more research was needed (WHO 2020b). On 1 December 2020, the WHO revised its guidelines again (WHO 2020c). This time it also recommended the use of face coverings in indoor settings where ventilation is poor. Aerosol transmission – described earlier as ‘misinformation’ – was now clearly implied to be a relevant factor in the spread of the virus. Without acceptance of this theory, the new recommendation would lack structural coherence. This is partly acknowledged, at least as a possible explanation: ‘Outside of medical facilities, in addition to droplet and fomite transmission, aerosol transmission can occur in specific settings and circumstances, particularly in indoor, crowded and inadequately ventilated spaces, where infected persons spend long periods of time with others’ (WHO 2020c). However, ‘high quality research’ is said to be required and the overarching theory is still that ‘SARS-CoV-2 mainly spreads between people when an infected person is in close contact with another person’ (our emphasis). Despite the change of advice, the WHO claimed that ‘there is only limited and inconsistent scientific evidence to support the effectiveness of masking of healthy people in the community’ (WHO 2020c).

Figure 3.1 WHO Fact Check tweeted 29 March 2020

Within the space of nine months, advice issued by the WHO had thus changed from warning against the risk of community masking to encouraging its use. Meanwhile, the theoretical underpinning of the advice had shifted from denouncing airborne transmission as misinformation to including it as evidence, albeit reluctantly. Importantly, at no time did the WHO publicly correct its earlier statements and at the time of writing has not deleted its tweets and fact sheets supporting its original take on the issue of face masking. Its warnings against spreading ‘misinformation’ about aerosol transmission still appear on several platforms alongside its new recommendations, which are informed by the same theory it had previously rejected. In a debate with aerosol scientists on 9 April 2021, Professor John Conly, who is part of the WHO’s group of experts advising on coronavirus guidelines, admitted that there might be ‘situational’ airborne transmission but that he would still ‘like to see a much higher level of scientific evidence’.Footnote 2 However, he did not offer any explanation of what ‘situational’ means in this respect and whether it refers to any indoor situation, in which case, as noted in one of the numerous tweets commenting on the debate, ‘that’s kind of a common situation’.Footnote 3

National guidance on the use of face masks has also changed during the pandemic and varied significantly between different nations and regions. A number of Asian countries recommended the use of medical masks by the public very early in the pandemic, and this recommendation did not result in any controversies. Reference GoodmanGoodman (2020) suggests that the high levels of compliance with face masking in Asian countries is due to the fact that ‘they never forgot the lessons of the Manchurian plague’ in 1910–1911, when bodies piled up on the streets of Harbin and more than 60,000 people lost their lives within the space of four months. This was when a young doctor by the name of Wu Lien first introduced the idea of masking. He ‘wrapped the faces of health workers and grave diggers in layers of cotton and gauze to filter out the bacteria, creating the ancestor of the modern N95 respirator mask’. He also urged everyone to cover their faces, having realized that the disease was ‘carried through the air, in respiratory droplets from breath’ (Reference GoodmanGoodman 2020). Wu was the first Chinese to win the Nobel Prize and thus remains a source of pride for his compatriots. In narrative paradigm terms, he possesses a very high level of characterological coherence and his scientific legacy remains credible. For Asian populations who had recently lived through the SARS outbreak in 2003, moreover, narratives that emphasize the need to take the pandemic seriously and adopt precautionary measures to protect the population from it also resonate strongly. Reference GoodmanGoodman (2020) suggests that while face masks were also widely used to control the 1918 flu pandemic, their importance seems to have been forgotten in the West.

Unlike Asian countries, Norway and Sweden continued to restrict their advice to specific situations. In August 2020, Norwegian health authorities recommended the use of face masks on public transport in situations where high levels of transmission are likely and when a physical distance of one meter cannot be maintained, for instance during the rush hour (NIPH 2020a). In October 2020, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) extended the recommendation to all situations where a high level of transmission is likely and where it is difficult to maintain a safe distance. It further emphasized that face masks could be used in addition to but not to replace other measures (NIPH 2020b). Physical distancing and hand hygiene were however considered the ‘most important measures to prevent infection’, and the primary transmission route is to date believed to be droplet infection. Sweden’s policy on face masks has been even more restrictive. As mentioned in Chapter 2, the country’s chief epidemiologist, Anders Tegnell, explicitly warned against the use of masks because it ‘would imply the spread is airborne’, which would ‘seriously harm further communication and trust’ (cited in Reference VogelVogel 2020). In December 2020, the Swedish government modified its policy and recommended face coverings on public transport for people born in 2004 or earlier, and only on working weekdays between 7:00 and 9:00 and from 16:00 to 18:00.

The incoherence of public health recommendations must be understood against the backdrop of inconsistencies in the scientific discourse throughout the pandemic. Policy recommendations tend to draw heavily on systematic reviews of scientific literature, which summarize and draw conclusions based on the current state of the art. However, many of the systematic reviews on face coverings in the context of Covid-19 reached contradictory conclusions despite being broadly based on the same body of evidence. While Reference Greenhalgh and HowardGreenhalgh and Howard (2020), for instance, reached a conclusion that strongly supported the use of face masks, Reference Brainard, Jones, Lake, Hooper and HunterBrainard et al. (2020) concluded that ‘evidence is not sufficiently strong to support widespread use of facemasks as a protective measure against COVID-19’. As Reference GreenhalghGreenhalgh (2020a) has pointed out in a blog piece on the website of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, the difference between these and other conflicting views seems to arise not from what the evidence is but from what it means. She emphasizes five areas of contestation in the face-masking controversy which underpin the structural and material incoherence evident in institutional narratives:

Is the absence of a definitive randomised controlled trial, along with the hypothetical possibility of harm (for example from risk compensation) a good reason to hold back from changing policy? …

Should we take account of stories reported in the lay press, such as those of single individuals apparently responsible for infecting dozens and even hundreds of others at rallies, prayer meetings or choir practices? …

Should we extrapolate from laboratory experiments on the filtration capacity of different fabrics to estimate what is likely to happen when people wear them in real life? …

Should we use anecdotal reports of some people wearing their masks ‘wrongly’ or intermittently to justify not recommending them to everyone? …

Should we take account of the possibility that promoting masks for the lay public may lead to a shortage of precious personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare workers? … .

Linked to this discussion is also a debate about how to use the precautionary principle in the context of face masks. The standard approach, which has been defended by some, suggests caution in the uptake of innovations with known benefits but uncertain or unmeasurable downsides, as in the case of the implementation of new pharmaceutical treatments (Reference Martin, Hanna and DingwallMartin et al. 2020a). At the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, for instance, John Ioannidis – a specialist in epidemiology, population health and biomedical data science at the Stanford School of Medicine – called attempts to impose what he saw as ‘draconian political decisions’ such as mandating the use of face coverings in the absence of evidence ‘a fiasco in the making’ (Reference CayleyCayley 2020). Reference GreenhalghGreenhalgh (2020b), by contrast, has suggested a supplementary approach that advocates precaution in the case of non-intervention when serious harm is already happening and a proposed intervention may reduce that harm. It is worth noting that a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of public health measures to reduce the incidence of Covid-19 – specifically, handwashing, face masking and social distancing – published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) on 18 November (Reference Talic, Shah and WildTalic et al. 2021) reported that face masking led to ‘a 53% reduction in covid-19 incidence’, but concluded that ‘more high level evidence is required to provide unequivocal support for the effectiveness of the universal use of face masks’. Well over a year after the mandate on wearing face masks in public was imposed and then lifted in many countries, the evidence from randomized controlled trials was still not conclusive. The jury remains out on this particular issue at the time of writing, and the controversies and contradictions continue to plague public policy.

More broadly, these conceptual inconsistencies also relate to different understandings of what counts as evidence in a public health context. Evidence-based medicine (EBM) has partly grown out of scepticism about the value of mechanistic reasoning as the foundation for clinical decision making. While the key characteristic of clinical decision making prior to the emergence of EBM was reliance on knowledge of mechanisms in the human body to make predictions about the outcomes of interventions, EBM reasoning relies on treatment recommendations distilled from experimental studies of interventions, for which no mechanistic justification may be known (Reference AndersenAndersen 2012). This partly explains why some EBM proponents (including health authorities like the WHO) can live with inconsistencies between mask recommendations and their mechanical justifications, although these inconsistencies might be very confusing for people less familiar with the fundamental presuppositions of the relevant scientific paradigm. In public health, however, interventions are most often developed and tested pragmatically and locally. Natural experiments are highly valued and evidence is drawn from a whole range of different sources, including individual experiences of interventions in local settings and basic science research (Reference GreenhalghGreenhalgh 2020b). In the context of the pandemic, we have experienced a clash between these different paradigms of evidence, which in turn has led to incoherence and confusion about the conclusions to be drawn from the scientific evidence. We have also been exposed to the limits of applied science in general in the context of a raging pandemic that does not allow enough time for conflicting scientific studies to be replicated and fine-tuned. As David Kriebel, Professor of Epidemiology at the University of Massachusetts-Lowell, argues, ‘science is self-correcting, given enough time. But currently there is not enough time for science to self-correct when it’s being used to craft public health policy’. His advice is that rather than ‘clamoring for scientific studies to back up mandates on mask use’, we should seek more transparency in public health messaging and share the uncertainty with the public – tell people honestly: ‘Mask use is our best judgment right now, and we will tell you if we get more evidence’ (quoted in Reference SoucheraySoucheray 2020).

The debate about the use of masks in schools has added a new layer of complexity to the epistemic controversies that characterize scientific enquiry. From merely being a debate involving different public health opinions and divergent understandings of what counts as evidence in a public health setting, the various arguments now draw on several other forms of expertise and have become a source from which evidence of material incoherence may be drawn. The answer to whether face masks should be recommended in the school setting largely depends on how the question is framed and which experts are called upon to answer it. Researchers in educational and behavioural science, for instance, have emphasized how wearing masks can affect the ability to communicate and interpret the expressions of teachers and other students and thereby negatively impacts learning and social bonding in the school setting (Reference SpitzerSpitzer 2020). Some scholars have also claimed that the use of face masks can trigger anxiety and fear among children and even harm their cognitive development (Deoini 2021).

Indeed, public recommendations regarding the use of face masks in schools have been even more confused than the general advice on their use in other settings. In the UK, the prime minister Boris Johnson stated in August 2020 that the idea of school children wearing face masks in classrooms is ‘clearly nonsensical’: ‘You can’t teach with face coverings and you can’t expect people to learn with face coverings’ (Reference DevlinDevlin 2020). Yet, in one of the many U-turns that have characterized public policy during the pandemic, he ‘bowed to pressure’ a few hours later and changed the guidance ‘after scores of headteachers broke ranks to urge their use, backed by [the] Labour [Party] and trade unions’ (Reference Elgot and HallidayElgot and Halliday 2020). In March 2021, the Department for Education updated its advice on face coverings following the spread of new, more transmissible variants of the virus. The guidance was now for ‘pupils and students in year 7 and above’ and their teachers to ‘wear face coverings indoors, including classrooms, where social distancing cannot be maintained’ (Department of Education 2021). By July 2021, the legal requirement to wear a mask was removed in England, except in hospitals and care homes. In November of the same year, Boris Johnson – the head of the same government that still mandated the use of face masks in healthcare settings – was severely criticized and forced to apologize when he was seen walking without a mask in the corridor in Hexham Hospital, Northumberland (Press Association 2021). Such U-turns and frequent changes in policy have been used as evidence of structural incoherence by the so-called ‘Us for them’ movement, an anti-mask, grassroots schools campaign backed by thousands of parents and pupils. An open letter to the UK Education Secretary, published on their site, asks for evidence to support the change in policy and points out:Footnote 4

Last Summer, the Government said masks in classrooms were unnecessary. The Prime Minister described it as ‘nonsensical’ and said that ‘you can’t teach with face coverings and you can’t expect people to learn with face coverings’. Your own department’s August guidance said that they ‘can have a negative impact on learning and teaching and so their use in the classroom should be avoided’.

Numerous other challenges to the guidance on wearing face masks in schools rely on pointing out aspects of the structural and/or material incoherence of institutional narratives, within and across different countries. The following two comments on an article published in The Telegraph on 26 August 2020 under the title ‘We will have a generation of scarred children’ demonstrate the challenge to both types of incoherence – structural and material:

@AJ Boyle

Face masks send out a message that there’s danger, therefore by logic it’s not safe for schools to open.

The teachers that don’t want to work now have a point.

You can’t have it both ways Boris, it’s either one or the other.

@Marvin Taylor

My kids went back to school here in Norway back in May, then a few weeks later had their summer holidays. Now they are back again and things are almost back to normal.

Not once did they have to wear face masks.

The article itself is interestingly attributed by the newspaper to its readers, rather than to The Telegraph,Footnote 5 alerting us to the role played by the media in amplifying and sanctioning particular arguments for or against public policies and the values that underpin them.

‘We will have a generation of scarred children’ – Telegraph readers on face masks in schools

Telegraph readers have had their say on face masks in schools

– Headline from a Telegraph article

Those for whom a mainstream broadsheet such as The Telegraph represents a credible and trustworthy source of information and sober views – in other words, for whom the paper possesses a high level of characterological coherence – will conclude from such coverage that there is a genuine ground swell against the use of face masks in schools, that many parents have real and rational concerns about the dangers associated with them, and will be encouraged to rethink their own take on the issue if it is at odds with this coverage. What is at work in such instances is part of a process of narrative accrual, an important dimension of how narratives evolve and gain adherence over time (Reference BrunerBruner 1991; Reference BakerBaker 2006). Narrative accrual means that repeated exposure to a set of related narratives and their underlying values gradually shapes our outlook on life, and ultimately the transcendental values that inform our judgements and are at the heart of the logic of good reasons, to which we turn next.

3.2 Transcendental Values, Narrative Accrual and Narrative Identification

While some of those who have argued against the use of face masks have expressed their concerns in measured language and explained them with reference to scientific evidence, or lack of it, others have acted in ways that are strongly confrontational, and often violent towards others. From the unmasked protestors in Trafalgar Square who carried signs with slogans such as ‘masks are muzzles’ and ‘Covid is a hoax’ (Reference PhiliposePhilipose 2020, in The Indian Express), to those who stood outside the Sephora Beverley Hills Beauty Store chanting ‘No More Masks’ and holding pieces of paper with messages such as ‘Sephora Supports Communism’ or shouting ‘Sephora is agent of Chinese government’ (Reference WittnerWittner 2021), behaviour that would normally be seen as bizarre and restricted to a small fringe seems to have become the order of the day during the Covid-19 crisis. The logic of good reasons and the concept of transcendental values allow us to understand some but not all such responses to face masking, for as Reference McClureMcClure (2009:205) explains, the problem with the concept of fidelity is that ‘belief in a story is accounted for by the fact that it’s already believed without ever having to explain why it’s believed in the first instance’. In what follows, we draw on Reference BrunerBruner (1991) and Reference McClureMcClure (2009) where necessary to address this weakness in Fisher’s model and make sense of some of the beliefs and behaviour that appear resistant to explanation in terms of the narrative paradigm alone.

Reference FisherFisher (1987:114) acknowledges that human beings are not identical and do not share the same values, that ‘[w]hether through perversity, divine inspiration, or genetic programming’, people make different choices and these choices ‘will not be bound by ideal or “perfect” value systems – except of their own making’. The idea that values are of people’s own making leaves the issue of how we come to embrace certain values rather than others rather vague. And while the narrative paradigm suggests that different values that inform the choices we make are a product of the narratives we come to believe in, Fisher does not directly explain why we come to believe in specific narratives rather than others, beyond stating that ‘the production and practice of good reasons’, which is informed by the narratives we subscribe to, ‘is ruled by matters of history, biography, culture, and character’ (Reference FisherFisher 1985b:75).

The concept of narrative accrual (Reference BrunerBruner 1991) can shed some light on the process by which certain values come to be ratified through the accrual of a network of related narratives to which we are repeatedly exposed over time. As we have seen in the previous section, the media – including social media – constitute an important site through which particular types of narrative accrue and come to impact the values of those exposed to them over time. Other such sites include the family, circle of friends, the educational system, professional groups, the film and videogaming industry and religious institutions, among others. Narrative accrual validates certain values and invalidates others over an individual’s lifetime, with networks of related narratives ultimately combining to form a tradition or (sub)culture whose members share a similar outlook on life. The (transcendental) values we acquire through this process become so ingrained that questioning them threatens our very sense of identity and ability to make sense of the world.

Alongside narrative accrual, there is also our basic human need to feel part of a community with a shared outlook on life. Reference McClureMcClure (2009:204) thus suggests that ‘many widely accepted narratives that defy both probability and fidelity’ can only be understood by appeal to the concept of identification. Fisher does draw on this concept in developing his model, but as Reference StroudStroud (2016) explains, he ‘casts identification as an outcome when a reader encounters a narrative that is judged to be high in narrative probability and narrative fidelity’. Stroud sees this as a strength of the narrative paradigm, but Reference McClureMcClure (2009:198) convincingly argues that it restricts ‘processes of identification to the normative criteria of the rational-world’, ‘unnecessarily limits our understanding of the rhetoricality of narrative’ (Reference McClureMcClure 2009:191) and hence underestimates ‘the irrational resources of identification, those “puzzlements and ambiguities,” those “enthymemic elements,” and those “partially ‘unconscious’ factors” that are at work in the everyday narratives by which we live’ (Reference McClureMcClure 2009:199). We follow McClure in treating identification not as an outcome of a successful test of probability and narrative fidelity, but rather as part of the definition of good reasons, acknowledging, with him (Reference McClureMcClure 2009:202), that ‘[w]hat changes by reconceptualizing identification in the narrative paradigm, is what counts as “good reasons.” And what counts as good reasons is identification’.

3.2.1 The Logic of Good Reasons, Narrative Accrual and Identification: Public Safety and Structural Racism

A strong cultural association between thugs, gangsters and face coverings has been gradually ratified in Anglophone and European societies through the accrual of a whole range of narratives to which we are repeatedly exposed through various sites and media. This cultural association has been evident in the context of the current pandemic, for instance when concerns are raised with respect to whether the use of face masks for medical purposes might pose a threat to public safety. A New York based lawyer, Kevin O’Brien, posed the question in a blog post titled ‘Are coronavirus policies aiding criminal activity?’ (Reference O’BrienO’Brien 2020). His answer points to the structural and material incoherence that exists between anti-masking laws still in force in several American states and pro-mask regulations in the context of Covid-19. While acknowledging that anti-masking laws have exacerbated social injustices, as in cases where they have been used ‘to arrest masked Antifa members for the act of wearing a mask, even where they have not committed any violent acts’, O’Brien also claims that these laws ‘aid law enforcement in numerous ways’. He backs this claim by referring to criminological studies demonstrating that anonymity is ‘commonly linked to deviant behavior’ and goes on to argue:

But the result of these Coronavirus compliant policy changes appears to be immediate, and dramatic – with the vast majority of people wearing masks, it is extremely difficult for law enforcement to identify who is inciting the violence, particularly when they are not members of the local community. I might be able to recognize my neighbor in a mask and a hood, but could I identify a stranger? Without this method of tying a specific individual to a specific act, elected officials and others seem to be more prone to speculate as to who is behind the violence and people seem more likely to commit crime.

Whatever you think of current recommendations and mandates regarding masks to combat Coronavirus, it seems these decisions are making it easier for some individuals to anonymously break the law – increasing the risk for communities that public health policies are designed to protect.

Newspaper headlines linking face masks to criminal activities also contribute to the steady accrual and hence resonance of this narrative. An article in The Telegraph published on 21 March 2021 and entitled ‘Gang members wearing coronavirus medical masks to disguise themselves’ (Reference LoweLowe 2020) reinforces the narrative of medical masks being used by people with criminal intentions to evade police detection. The article quotes a charity officer who works with high-risk offenders across the southeast of England arguing that face masks might be used to support anti-social behaviour: ‘There could be some level of disorder in terms of anti-social behaviour. Just today in Wood Green, a young offender came up to me wearing a protective mask and offered me some marijuana’.

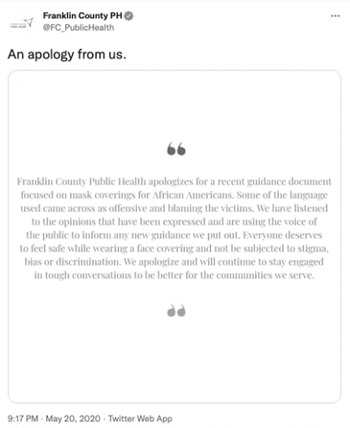

This link between criminal activity and masking is particularly associated with citizens who are (perceived to be) of non-Western origin – those who are classed in nationalistic narratives as ‘non-indigenous’. In April 2020, the Franklin County Public Health Board in Ohio released a document addressed to ‘communities of colour’ about wearing face masks that they were later forced to withdraw (Franklin County Public Health 2020). The document advised black Americans to avoid using face coverings made of ‘fabrics that elicit deeply held stereotypes’: ‘It is not recommended to wear a scarf just simply tied around the head as this can indicate unsavoury behaviour, although not intended’. The Franklin County Public Health later tweeted an apology and admitted the guidance ‘came across as offensive and blaming the victims’ (Figure 3.2).Footnote 6 Still, well intentioned or otherwise, such statements can impact the values of all who come across them, but particularly those to whom they are addressed and who are singled out in this narrative as a source of concern for the community and hence as positioned outside it. Importantly, they restrict the ability of such addressees to identify with the larger community and see its welfare as coherent with their own, and to view the advice given by its institutions as ‘represent[ing] accurate assertions about social reality and thereby constitut[ing] good reasons for belief or action’ (Reference FisherFisher 1987:105).

Figure 3.2 Franklin County Public Health Board apology

Black citizens, in turn, have reportedly been hesitant to wear a mask in public because of the racist fears it evokes. A black physician in Boston raises the issue of how the act of making face masks mandatory in public might affect people of colour in a blog post titled ‘Wearing a face mask helps protect me against Covid-19, but not against racism’ (Reference FelixFelix 2020):

As a physician, I favor things that will help reduce the transmission of coronavirus infections. But as a Black man, I wondered how this order will affect people who look like me. I wondered if this order went into effect with any understanding of the fear and anxiety it could inflict on people of color.

That might sound irrational to some. But it resonates with many Black people, who are far too familiar with having to interact with law enforcement for appearing ‘suspicious’ and in many instances having to fear for their life during these interactions.

Felix details how, being not only black but also 6 feet two inches tall, his ‘decision-making’ process had to be quite complex: ‘[it] went as far as limiting how often I went out after dark, knowing that some people will see a masked Black man as a threat’. Such cultural stereotypes and the racist anxieties they evoke are deeply embedded in a larger narrative of white supremacy that has accrued over many centuries, a narrative that assigns inferior status to numerous communities who are repeatedly cast as a source of threat to the nation proper. Reference ZineZine (2020) thus argues that ‘the concept of white privilege can be related to how COVID-19 mask-wearing is seen differently when worn on racialized bodies’. While masked black faces are associated with criminality, masked Asian faces are seen as an emblem of the crisis itself. ‘Instead of representing a good citizen helping to stop the spread of a possible contagion, a protective mask transforms Asian bodies into the source of contagion’. Zine further points to the structural incoherence of the French mandate to wear masks which has not been accompanied by a lifting of the ban on women wearing a niqab, citing the French researcher Fatima Khemilat’s comment on the irony of this situation:

If you are Muslim and you hide your face for religious reasons, you are liable to a fine and a citizenship course where you will be taught what it is to be a good citizen … But if you are a non-Muslim citizen in the pandemic, you are encouraged and forced as a ‘good citizen’ to adopt ‘barrier gestures’ to protect the national community.

A similar irony – or structural incoherence in Fisher’s terms – has pervaded the discourse of European leaders. In 2018, well before the outbreak of the pandemic, Boris Johnson stated that as a Member of Parliament he felt ‘fully entitled’ to see the faces of his constituents, describing women who wore the niqab as looking like letterboxes and bank robbers.Footnote 7 And yet, as noted in an article titled ‘Veiled racism: how the law change on Covid-19 face coverings makes Muslim women feel’, published in The Independent on 26 June (Reference BegumBegum 2020),

[f]rom 15 June 2020, Boris Johnson – the same politician who caused a wave of anti-Muslim sentiment with his column in 2018 – has made it mandatory that all people in England wear face coverings on public transport. As well as encouraging them in other places it is hard to social distance like shops or supermarkets. The government even issued guidelines on how to make your own face covering at home.

These and similar inconsistencies in policies and statements by political leaders serve to amplify racist fears and anxieties among those who are exposed to them and undercut the possibility of identification with the larger community among those cast as threatening to the nation’s way of life and security. Black, Asian and Muslim members of these societies who do not comply with mandatory measures such as wearing face masks in public areas, or who do so under duress and without believing that applying these measures is genuinely in their interest, are not ‘irrational’. Their behaviour is informed by considerations that are narratively – if not scientifically – rational and that reflect their own lived experience, both prior to and during the pandemic. Ultimately, as Reference MarcusMarcus (2020) argues, ‘combatting racism is inextricable from public health’, as indeed are so many social issues such as poverty, unemployment, trust in political and social institutions, and much else.

3.2.2 Good Reasons, Precarious Manhood and Homophobia

Identification, as Reference McClureMcClure (2009:202) argues, constitutes good reasons for action and belief in and of itself. The examples of racism against black, Asian and Muslim people discussed above suggest that those at the receiving end of racism will find it difficult to identify with the larger community and trust its institutions. Similarly, narratives of masculinity and homophobia may serve to pressurize those socialized into them to act in ways that are consistent with the values they promote and that have been reinforced during the crisis by high-profile personalities, as we detail below. In other words, they pressurize them to behave in ways that are ratified by the group with which they identify.

Masculinity and homophobia have impacted responses to face masking during the Covid-19 crisis in various ways. Narratives that cast heterosexual men as strong, hardened, no-nonsense members of the ‘real’ community and gay men as effeminate, feeble and repulsive have been accruing in all societies around the world for centuries. Many men, in all cultures, are socialized to varying degrees into thinking that manhood is a highly desirable character trait and tend to associate it with physical strength and fearlessness. This ‘performative masculinity’, as Reference Abad-SantosAbad-Santos (2020) calls it, rests on ‘a narrow vision of manhood that ignores other tropes like self-sacrifice and being a protector’, but it has proved very powerful during the pandemic. As The New York Times acknowledges,Footnote 8 ‘the best public health practices have collided with several of the social demands men in many cultures are pressured to follow to assert their masculinity: displaying strength instead of weakness, showing a willingness to take risks, hiding their fear, appearing to be in control’. And indeed, numerous polls have shown that many more men than women refuse to wear face masks, most notably in the USA, urging commentators like Reference Abad-SantosAbad-Santos (2020) to ask in disbelief:

Fellas, is it gayFootnote 9 to not die of a virus that turns your lungs into soggy shells of their former selves, drowning you from the inside out? Is wearing a mask to avoid death part of the feminization of America? Is it too emasculating to wear a mask to protect the others around you? Does staying alive make you feel weak?

Persistent socialization into the dominant narrative of masculinity means not only that manhood is understood as ‘innate’, something a ‘real’ man is born with, but also that it is ‘simultaneously precarious and in need of defending’, leading those who value masculinity to ‘overperform’ their manhood and ‘police its lack in others’ (Reference McBeeMcBee 2019). Refusing to wear face masks and ridiculing others who do provided an opportunity for many to demonstrate their manhood during the crisis, encouraged by high-profile male personalities engaged in their own overperformance of manhood. In October 2020, for instance, The New York Times reported that Joe Biden posted a picture of himself on Twitter wearing a mask, in response to which ‘Tomi Lahren, a conservative commentator and Fox Nation host’ declared that Biden ‘might as well carry a purse with that mask’.Footnote 10 Some evangelists in the USA called men who chose to wear face masks ‘“losers,” “pansies” and “no balls”’ (Reference HarsinHarsin 2020:1065). The Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro is reported in the leading broadsheet Folha de São Paulo to have ‘baited presidential staff who were using protective masks, claiming such equipment was “coisa de viado” (a homophobic slur that roughly translates as “for fairies”)’ (Reference PhillipsPhillips 2020). The same broadsheet reported that despite the alarming spread of the virus in Brazil at the time, ‘Bolsonaro insisted on greeting visitors with a handshake and shunned masks’. This brand of ‘toxic white masculinity’, as Harsin describes it, was ‘showcased in some popular COVID-19 responses (Trump, Bolsonaro and Orban, most spectacularly)’, and can be ‘described as “toxic” or “fragile”’ because it is ‘threatened by anything associated with perceived femininity; it is further associated with physical strength, sexual conquest, a lack of any emotions signifying vulnerability (except for aggressive ones), domination, control and violence’ (Reference HarsinHarsin 2020:1063).

In an article in Scientific American, Reference WillinghamWillingham (2020) called masks ‘condoms of the face’, comparing men’s resistance to wearing masks to their refusal to use condoms during the HIV pandemic. Willingham explains this resistance in terms of a ‘white masculine ideology’ associated with adventure, risk and violence, whose ‘high priest’ is Donald Trump. By refusing to wear masks, men who have been socialized to think of themselves in these terms ‘expect that their masculine ideology group will accept them, respect them and not reject them’. The editor of the conservative religious journal First Things, R. R. Reno, defended the rejection of face masks in terms that confirm Willingham’s analysis: in one out of a series of tweets (that were later erased) he insisted that ‘[t]he mask culture is fear driven. Masks + cowardice. It’s a regime dominated by fear of infection and fear of causing of infection. Both are species of cowardice’ (quoted in Reference KristianKristian 2020). In a subsequent tweet, Reno challenged his audience to declare themselves fearless or cowardly. ‘There are those who are terrified, and those who are not. Where do you stand?’. Like the Young Earth Creationists McClure uses to exemplify how narrative identification works, many men continue to invest in white masculine ideology because ‘rejecting it has the implication of undermining the larger narrative(s) of which it is a part and rejecting the larger community to which they belong” (Reference McClureMcClure 2009:207).

Julia Marcus, an epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School, argues in an article in The Atlantic that public health authorities should acknowledge and address such values rather than condemning them. ‘Acknowledging what people dislike about a public-health strategy enables a connection with them rather than alienating them further’, she suggests (Reference MarcusMarcus 2020). Like Reference WillinghamWillingham (2020), she compares men’s refusal to wear face masks with their reluctance to wear condoms during the HIV pandemic. Just as companies began to make condoms that not only protect people but also address their need for pleasure and intimacy, she argues, governments should now ‘support businesses in developing masks that are not only effective, but … that make them feel stylish, cool, and – yes – even manly’ (Reference MarcusMarcus 2020). This is sound advice, as far as it goes, and following it could make wearing masks more palatable for some of those who regard them as ‘unmanly’, though it arguably also runs the risk of giving more credence and legitimacy to toxic masculinity. More importantly, unlike condoms, masks are worn in public and hence exacerbate the need for ‘precarious manhood’ to be asserted. The implications of wearing them or otherwise are further complicated by their association with specific political positions, leading a public health professor at Morgan State University in the USA to comment that ‘[w]e’re seeing politics and science literally clashing’. The BBC news report that quotes him agrees (Reference McKelveyMcKelvey 2020):

The wearing of masks has become a catalyst for political conflict, an arena where scientific evidence is often viewed through a partisan lens. Most Democrats support the wearing of masks, according to a poll conducted by researchers at the Pew Research Center.

Most Republicans do not.

Writing some two months later (in August of the same year), Reference Abad-SantosAbad-Santos (2020) reports that sports companies like Nike and Under Armor are already ‘making masks that superheroes might don’, including some that are curved like shark fins and one, by GQ, that makes its wearer look like he’s ‘in Mortal Kombat’. Abad-Santos points to a further complication that undermines the value of attempts to appeal to masculine imagery in order to encourage more men to wear masks. ‘For men concerned with masculinity, the appeal here is that these masks not only look cool but allow you to do masculine things like run faster, lift heavier, and be stronger’. This means that manufacturers use porous material ‘which is designed to be breathable and in fact breaks up larger particles, allowing them to hang around in the air longer’, and making people wear these masks is possibly worse than them not wearing masks at all (according to Abad-Santos). Any advice on how to address resistance to face masks must therefore consider a wide range of factors that have arguably made the Covid-19 crisis more challenging to public health policy makers than most pandemics humanity has faced in the past.

3.3 Beyond Precariousness: Personal Freedom vs Social Responsibility

Perhaps the most fundamental value commitment underpinning the debates about face coverings is the notion of individual freedom. Controversies around different understandings of this transcendental value, as well as how it relates to social responsibility, have dominated much of the current debate, implicitly or explicitly. Anti-mask protests have occurred in many countries in response to mask mandates, some claiming that such mandates ‘sacrifice individual liberty to a collectivist notion of a “greater good”’ (Reference BluntBlunt 2020). The conception of ‘freedom as non-interference’ that inspires these protests has also elicited support from prominent figures on the political right in the UK and America: Peter Hitchens of the Daily Mail, for instance, referred to face coverings as ‘muzzles’ (Reference HitchinsHitchins 2020) while Michael Savage, a prominent radio talk host, called masks ‘a sign of submission’ (Reference WalkerWalker 2020).

Similar ‘us’ vs ‘them’ dichotomies have been implicitly evoked to argue that the use of face masks might be acceptable for certain populations but is at odds with the values of freedom underpinning Anglophone and European societies. Having denounced face masks as ‘muzzles’, Peter Hitchins went on to declare that their mandatory use marked

the final closing down of centuries of human liberty and the transformation of one of the freest countries on Earth [the UK] into a regimented, conformist society, under perpetual surveillance, in which a subservient people scurries about beneath the stern gaze of authority.

In a blog post on the Architects for Social Housing website, entitled ‘The science and law of refusing to wear masks: texts and arguments in support of civil disobedience’, Reference ElmerElmer (2020) considers the general use of face masks in Asian countries against the backdrop of the ‘arsenal of surveillance tools’ available to the governments of China, Hong Kong, South Korea and Taiwan to track and monitor their populations. As part of this arsenal, he lists the mass surveillance of mobile phone, rail, credit card and flight data, including the use of ‘facial recognition algorithms to identify commuters who aren’t wearing a mask or who aren’t wearing one properly’, among many other such intrusive practices. These technologies of surveillance, he argues, are now being advocated for use in the West and must be confronted through civil disobedience if necessary. Elmer supports his claim by quoting an article published in the influential Foreign Affairs by Nicholas Wright, a UK medical doctor and neuroscientist, in which he (Wright) insists that ‘Western democracies must rise to meet the need for “democratic surveillance” to protect their own populations’, that ‘they must be unafraid in trying to sharpen their powers of surveillance for public health purposes’, and that ‘there is nothing oxymoronic about the idea of “democratic surveillance”’ (Reference WrightN. Wright 2020). Elmer then rebuts Wright’s argument by recalling the words of Giorgio Agamben, the well-known Italian philosopher who criticized the Italian government’s use of the coronavirus as a warrant for implementing a permanent state of emergency (Reference AgambenAgamben 2021:48):

A norm which affirms that we must renounce the good to save the good is as false and contradictory as that which, in order to protect freedom, imposes the renunciation of freedom.

Some have linked this debate about face masks and protecting vs renouncing freedom to the distinction between negative and positive liberty, freedom from vs freedom to. This distinction, which underpins two opposing sets of transcendental values – both narratively rational and both providing good reasons for their adherents – goes back to Kant, who distinguished between freedom understood in negative terms as an absence of constraints, and freedom understood in positive terms as the possibility of auto-commencement (self-beginning, or Selbstanfang), in the sense of acting and taking control of one’s life. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains, ‘While negative liberty is usually attributed to individual agents, positive liberty is sometimes attributed to collectivities, or to individuals considered primarily as members of given collectivities’.Footnote 11 An appeal to positive liberty would sanction state intervention where required, whereas an appeal to negative liberty would favour placing strong restrictions on state intervention. In political philosophy, the classical liberal tradition, represented by philosophers such as Spencer and Mill, is seen as defending a negative concept of political freedom, while theorists critical of this tradition, such as Rousseau and Marx, are associated with a positive concept of political freedom. Reference MunroeMunroe (2020) implicitly sides with the latter view when in a commentary in The Herald he draws on this distinction to demonstrate how the debate about face masks brings the two understandings of freedom into conflict:

Requiring individuals to wear a face mask under penalty of fines does deprive them of a negative liberty, but it strengthens a greater liberty which can only be protected through coordinated public action, it creates conditions by which we can all safely access social services and businesses.

For Agamben, however, the freedom renounced through wearing face coverings goes beyond the negative definition of absence of constraints. Agamben sees the mandate of covering the face as a threat to the very condition of politics and the positive freedom of humans as political beings. While animals do not acknowledge their exposure or consider it a problem, as ‘they simply dwell in it without caring about it’, human beings ‘want to recognise themselves and to be recognised, they want to appropriate their own image, seeking in it their own truth’ (Reference AgambenAgamben 2020). The face, according to Agamben, is ‘the place of politics’, it is what reveals true investment in an argument and translates pieces of information into statements: ‘If individuals only had to communicate information on this or that thing, there would never be proper politics, but only an exchange of messages’ (Reference AgambenAgamben 2021:87). Based on this notion of politics, he concludes that ‘a country that decides to give up its own face, to cover the faces of its citizens with masks everywhere is, then, a country that has erased all political dimensions from itself’ (Reference AgambenAgamben 2021:87).

Ultimately, as Christos Lynteris – a medical anthropologist at the University of St Andrews in Scotland – notes, the reasons for failing or openly refusing to wear a mask are many and complex (Reference GoodmanGoodman 2020). In addition to the values and logics already discussed in this chapter, there are young people who are convinced that Covid-19 is an old people’s disease and cannot or is highly unlikely to affect them, leading them to treat it as a common cold or the flu; there are others for whom ‘refusal to wear a mask has become a visual symbol of being a free-thinker and nonconformist’ (Lynteris, in Reference GoodmanGoodman 2020); and there are others still who think masks are for Asians, not ‘us’, and are ‘a tool of communist control’ (Lynteris, in Reference GoodmanGoodman 2020). Whatever the beliefs that these individuals and communities entertain about wearing face masks, they are as rational to them as any piece of evidence-based scientific advice. They are strongly held because they are informed by narratives and values that have been acquired and reinforced through ongoing processes of socialization, by the need to identify with a particular community and by their own lived experience. The latter directly impacts the extent to which narratives about the benefits of wearing a mask and other health-related information may or may not resonate with particular publics such as the black community.