In 2007, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching published its influential study of legal education, Educating Lawyers.Footnote 1 In stressing that the formation of professional identity and purpose is central to the development of law students into lawyers,Footnote 2 Educating Lawyers introduced new language to the legal academy – but not a new mission. For generations, law schools have proclaimed the goal of graduating well-rounded and well-grounded new lawyers who have made good progress toward their socialization in the legal profession.Footnote 3 The problem that Educating Lawyers perceived was the failure of law schools to pursue the professional formation dimension of their educational work with anything like the intentionality and drive for excellence they exhibit when helping students to think like a lawyer.Footnote 4 Professional formation was left much to chance. It was the hoped-for consequence of the student’s travails in the bramble bush that is American legal education.Footnote 5

An all-important ingredient – purposefulness – has been missing. This book details how law schools can provide it, and we begin in this chapter with a framework to help faculty and staff bring that purposefulness to their support of professional formation. We introduce some ways to think about law students, their law school, and American legal education that we hope faculty and staff will find invigorating. There is no call to abandon prevailing approaches to the cognitive and skills dimensions of a law student’s education that Educating Lawyers labeled the first and second apprenticeships, respectively.Footnote 6 But when it comes to professional identity formation, the third apprenticeship, a shift in perspective will reveal opportunities with time, talent, space, and experiences. It can leave faculty and staff with a justified sense of optimism that effective support of professional identity formation is within reach.

2.1 How to Think about Professional Identity Formation

2.1.1 Choose a Workable Conception of Professional Identity

Purposefulness means being intentional about the right things, about focusing on the appropriate goals. Purposefulness about the formation of professional identity starts with a clear idea about what professional identity entails.

Educators in medical schools employ a definition that translates well to law: professional identity is “a representation of self, achieved in stages over time, during which the characteristics, values, and norms of the medical [or legal] profession are internalized, resulting in an individual thinking, acting, and feeling like a physician [or lawyer].”Footnote 7 For legal education, we recommended in Chapter 1 viewing professional identity as the student’s accepted and internalized

Ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence at the major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need;

a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client;

a client-centered, problem-solving approach and good judgment that ground the student’s responsibility and service to the client; and

This formulation of a lawyer’s professional identity rests on propositions rooted in the legal profession’s social contract and in a lawyer’s own self-interest in professional success: the expectation of excellence in the service provided to others and the necessity of the lawyer’s ongoing capacity to provide it. It is a general definition that references without specification “major competencies” that will require elaboration, and we will touch on what that means for the work of a law school in Section 2.1.3 and explore the issue extensively in Chapters 3 and 4. But at the outset, note how this conception of professional identity avoids distracting debates over subjective valuesFootnote 8 while inviting recognition of attributes like self-direction, leadership-of-self, and commitment to improvement that are as indispensable to a lawyer’s professional identity as they are critical to a law student’s success in school and in the employment marketplace. It is a unifying and workable definition in the law school setting.

As we noted in Chapter 1, this formulation also is a statement of four goals – the PD&F goals – for students to pursue. If any of the four PD&F goals has support among faculty, staff, or administrators at a particular law school, that school is poised to move forward in a purposeful fashion. As we discuss in Chapter 5, a key initial step is to assess the school’s local conditions to gauge faculty, staff, and administrator interest in these goals. With interest identified, a “coalition of the willing” can be formed to pursue a number of recommended steps to purposefully strengthen the school’s support of student progress toward the goals.

2.1.2 See the Formation of Professional Identity as Principally a Process of Socialization

A purposeful effort to support the formation of professional identity needs not only a workable conception of professional identity but also a solid sense of what formation means. Medical educators envision identity formation as principally a process of socializationFootnote 9 – an understanding that should resonate with lawyers and law professors. The professional-to-be begins as an outsider to the professional community and its ways, values, and norms. Through experiences over time, the individual gradually becomes more and more an insider, “moving from a stance of observer on the outside or periphery of the practice through graduated stages toward becoming a skilled participant at the center of the action.”Footnote 10 The process continues throughout one’s careerFootnote 11 and features “a series of identity transformations that occur primarily during periods of transition”Footnote 12 marked by anxiety, stress, and risk for the developing professional.Footnote 13 Educational theorists call the learning that occurs in this process of socialization “contextually situated”Footnote 14 – the product of the developing lawyer’s social interactions and activities in environments authentic to the legal profession’s culture and enriched by coaching, mentoring, modeling, reflection, and other supportive strategies.Footnote 15

The periods of transition that students experience stand out as important focal points for purposeful formation support – a principle we will explore more extensively in Chapter 4.Footnote 16 Law schools can identify the important transitions their students experience and tailor strategies to better support students through them. A good picture of the transition periods and their effect on competencies also can reveal developmental experiences that are missing and should be provided.Footnote 17

2.1.3 Recognize the Components of Professional Identity Formation and the Interrelationship between Them – and the Significance of Competencies

Newcomers to purposeful work in support of the professional identity formation of law students will encounter new topics and terms, and even different language to refer to the same concept. Legal educators come to the formation project from different starting points and with different understandings, expectations, and aspirations. There are many on-ramps to the work of supporting the student’s formation of professional identity.

There are staples of purposeful formation work, however, and it pays to locate them conceptually and appreciate the interrelationship between them. Here is a way of mapping them within the professional identity framework. The definition of professional identity that we recommend begins with a first foundational goal that calls on each student to develop toward excellence at all the major competencies of the profession. What are the major competencies of the profession to which this first PD&F goal alludes? How do those competencies relate to the other three foundational PD&F goals? And how do the PD&F goals relate to one another?

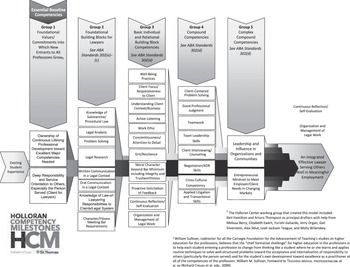

Figure 2 depicts the interrelationships among the four goals and all the other major competencies needed to be successful in the practice of law. Developed by a working group of the Holloran Center for Ethical Leadership in the Professions at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis, Minnesota, the model in Figure 2 includes all the competencies clients and legal employers need that were summarized in Chapter 1 and its Appendix, reorganized here into a progression of building blocks.

Figure 2 How the competencies that legal employers and client want build on each other

Figure 2’s Group 1 competencies make clear that new entrants into the legal profession (and, indeed, into all the professions) must internalize the first two foundational PD&F goals. Ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence at the major competencies and a deep responsibility and service orientation to others are essential to the developing professional’s progress toward achieving all the remaining particularized competencies in Groups 2 through 5. They are the heart of “being” a lawyer.

The Group 2 competencies include cognitive skills that legal education traditionally has prioritized and practical skills that law schools have emphasized increasingly in recent decades. These correspond to the first and second apprenticeships identified in Educating LawyersFootnote 18 and might be rendered colloquially as the skills that go into “thinking” and “doing” like a lawyer. Group 3 introduces to the picture a number of basic individual and relational building-block competencies, starting with the foundational PD&F competency (and goal) of well-being practices. Group 4 recognizes “compound competencies” that apply and build upon the foregoing. One such compound competency is client-centered problem solving – our third foundational PD&F competency (and goal). Group 5 acknowledges that there are yet more, and more complex, compound competencies that involve application of the foregoing competencies in settings and contexts that raise special challenges. The reader can see in Groups 1 through 5 that one or another of these diverse competencies might be of special interest to particular faculty, staff, or administrators at one’s own law school. As we have said, there are many on-ramps into the work of fostering the formation of each student’s professional identity.

No generally agreed-upon catalogue of all the competencies that one might locate in Figure 2 exists, and the law school has choices to make in creating the list of competencies that it will make the focus of its work in helping its students. Some competencies might be included because clients and legal employers affirm them as important to a lawyer’s success in the practice of law (as demonstrated, for instance, by the data reflected in Figure 1 in Chapter 1). Other competencies may be included because they appear in law school accreditation standards, requirements for admission to the bar, or applicable codes of ethics and professionalism.Footnote 19 Competencies also might merit inclusion because the faculty and staff believe the legal profession’s social contract calls for them, even if neither regulation nor the marketplace has so spoken. From the standpoint of ensuring purposefulness, the actual choices that the law school makes here matter less than the reasons for them. Let those reasons be clear and honest and open and accountable to the interests of all concerned, including students and external stakeholders who entrust law schools with the responsibility for legal education.

When the law school is identifying competencies, there likely will be references made to so-called hard skills and soft skills. Shorthand has its place, but a caution about its use here is in order. Labeling competencies as “hard” or “soft” involves neither science nor art, and the use of such labels can lead to unconscious indirection and the introduction of unspoken new considerations. Do the adjectives “hard” and “soft” suggest something about the comparative worth of the skill? If so, by what measures and according to whose values? Do the adjectives mean something about comparative rigor? If so, rigor on what axis, and with what relevancy to someone’s development as a lawyer? Do they refer to comparative amenability to teaching? If so, by what calculation, upon what assumptions about what it means to teach, and again with what relevancy? Using and giving weight to the labels “hard” and “soft,” without uncovering the premises and connotations that the adjectives might be masking, only makes purposefulness harder to attain. Better to steer clear of the adjectives and get to the real points instead.

Among competencies, the capacity for self-direction (sometimes addressed as self-directed learning, self-regulated learning, self-awareness, or leadership-of-self) occupies a crucial place because so much else turns on it.Footnote 20 The professional’s ability to pursue and maintain excellence depends on it, as does one’s ability to serve others responsibly and to provide leadership. Before serving and leading others, one must first be able to serve and lead oneself.Footnote 21 Research indicates that many law students are at relatively early stages of development with respect to self-directionFootnote 22 – making it all the more deserving of the law school’s attention. Faculty may not use the term self-direction, but they have the concept in mind when they contrast the unfocused, struggling student with the successful one who has command of law school’s challenges. Advisors in academic success programs have the concept in mind daily in their work, as do career services counselors when they report that students who take insufficient personal ownership of their job searches face greater difficulty obtaining meaningful employment upon graduation. A law school that prioritizes student success will not overlook self-direction and associated capacities like resourcefulness, resilience, and critical reflexivity.Footnote 23 The school also will recognize that faculty and staff across the enterprise can contribute to and profit from the school’s efforts to support development of these competencies.

An important final point about competencies: to say that a law school can improve its support of student professional identity formation by focusing more explicitly and purposefully on competencies is not the same thing as saying the school must adopt “competency-based learning” as its educational model. Under the competency-based learning model, a student progresses through a course of study by demonstrating proficiency at increasing staged levels of designated competencies – and not, as progress is structured under the traditional educational model of law schools, by accumulating credit hours that reflect time spent on various subjects.Footnote 24 As Chapter 3 explains, medical education has adopted the competency-based model and trends in American education suggest it is taking hold widely. The American Bar Association recently introduced accreditation standards that move law schools in that direction but, in application, stop short of full adoption of the model. For our purposes, it suffices to note that every school can profit by bringing purposefulness to its support of professional identity formation. Successful initiatives can be launched within either model and adapted easily for use in the other.

2.2 How to Think – And Not Think – About Supporting Professional Identity Formation

It is human to make assumptions that frame issues in ways that misdirect us or obscure possibilities. Four framing assumptions, reflecting familiar understandings about legal education, can distort a law school’s thinking about how to support professional formation. Examining them will bring to the fore new ways of thinking that better serve purposeful and effective efforts.

2.2.1 Think First and Foremost of the Student’s Socialization and Formation Experiences: What Law Faculty Do Is Important, but Only One of Many Means to the End

When law professors are asked how their school might be more purposeful in supporting professional formation, their thoughts likely turn immediately to things professors do (and might do differently) in their roles as teachers. There are right times and places for engaging in this reasonable way of thinking, but not at the outset.

This is a more important point than its simplicity might suggest. What law professors do is only a means to the relevant end here – the student’s personal development of a professional identity. Analysis that begins with means rather than ends runs the risk of missing the mark. Framing from the faculty perspective, rather than from the student’s socialization journey and what it entails, can exclude a world of possibilities from the picture.

Many factors that influence a student’s formation of professional identity lie beyond what the law school customarily contemplates legal education to encompass. When it comes to a student’s education in legal doctrine and the cognitive competencies of lawyering, the faculty’s role is dominant, with staff within the school and individuals and organizations outside the school playing smaller parts, if any. The formation of professional identity, on the other hand, is a socialization process affected by numerous other experiences that have much less to do directly with the professors. Consider student experiences in seeking and obtaining summer and postgraduation employment, or during internships or part-time employment, or in extracurricular activities. Those influential experiences happen at a time during the student’s law school years preceding professional employment, but not a time that the faculty customarily considers its immediate responsibility. They occur in a space that the student frequents during the law school years preceding professional employment, but not a space over which the faculty customarily assumes active jurisdiction. They occur in the proximity of people who influence the experience, but they are people other than the student’s professors – among them, career counselors, interviewing employers, moot court judges, lawyers in a student’s summer workplace or externship placement, attorneys invited to participate in brown bag lunches, formal and informal mentors, and peers on their own professional socialization journey.

Starting from the law faculty perspective constricts legal education’s palette, obscuring experiences, time, space, and talent that legal education has within its reach to better support the student’s formation of professional identity. It also brings vying priorities and interests to the fore before the potential benefits to student professional identity formation have been fully explored.

2.2.2 Think about Taking Responsibility and Asserting Leadership: What Law Schools Can Do Is Not Limited to “Teaching” by the Faculty

Law professors contemplating what their school can do to better help students in their formation of professional identity likely will presuppose that the answers involve some form of transmission of knowledge by the faculty to students. After all, isn’t that what teaching is, and isn’t teaching what a law school does?

Framing the law school’s capacities that way defines legal education and the law school’s appropriate functions too narrowly. Teaching as it is customarily envisioned – the transmission of expert knowledge by a professor who imparts doctrinal wisdom and hones student skills in analysis and synthesis – figures enormously. But the education of the American lawyer involves more. Other kinds of experiences are formative for the developing lawyer and thus, in a real and meaningful sense, an integral part of the legal education. The challenge for law schools is twofold: to see legal education in those broader terms and to recognize that society expects law schools to take responsibility for legal education in those broader terms. The social contract will hold law schools responsible for the pre-professional-employment period of a lawyer’s development in all its facets.

How do we know? Because law schools already are being held accountable for the outcomes of that developmental period, whether they realize it or not. Today, those outcomes are measured by successful admission to the bar and success in obtaining employment – and the accreditation regime, the rankings and reputational environment, and the admissions marketplace all impose accountability for them. Trends in higher education suggest the future will judge schools by an expanding array of alumni success measures. It is no answer to competitively disadvantageous outcomes that the law school conveys expert knowledge well. Law schools increasingly will be pressed to leave no professional development stone unturned.

Accepting this responsibility means embracing a leadership challenge. The question is not so much what additional expert knowledge the law faculty can convey, but rather what the school as a whole can do to maximize the formative potential of the pre-professional-employment period – what diverse talents, techniques, and resources it can muster and deploy. A purposeful effort will depend on three key steps.

First, it is necessary to be frank about the period for which the law school bears responsibility. The traditional “conveying of expert knowledge” way of thinking marks the start of this period at law school matriculation and its end at graduation, with the summers after the first and second years of law school characterized as “breaks.” Law schools now acknowledge, at least implicitly, that the period of their responsibility extends further because they explicitly treat their field of competition and marketplace accountability as extending further. The period really begins not with matriculation but with increasingly intensive recruitment and admissions processes that initiate the student’s professional socialization. The period ends not at graduation but with the passing of the bar examination and the securing of a job – activities that law schools support with expanded postgraduation services. And those summers are not “breaks” that punctuate the period but months designated for real-world experiences that schools promote and facilitate, and even create and subsidize, because they are central to development.

The second step is to draw into view the diverse formative experiences that occur (or could occur) in that pre-professional-employment period, together with the varied times, spaces, and talents associated with those experiences. These represent the assets that can be committed to supporting students in the formation of their professional identity. By inventorying the experiences carefully, and associating each experience with one or more of the competencies that the school sees as integral to its working conception of professional identity, the school can see with clarity the student’s development opportunities and the functions they serve. The first job interview, for instance, might be regarded as a critical developmental moment for a student’s self-direction and self-awareness competencies. A summer internship, on the other hand, might be the platform for developing a student’s responsiveness and teamwork skills.

A richer picture of the pre-professional-employment period allows the law school to move to the third step – the formulation of purposeful strategies to fortify each formation experience and to unite them all in a coherent, staged, sequenced, and supported whole that maximizes the benefits for students. It may be helpful to see this as a project with two dimensions. On a more general level, relationships and collaborations need to be forged among the many people and organizations that afford students formation experiences. Lines of communication between these parties need to be opened. Ways of coordinating, enhancing, reinforcing, and leveraging their varied efforts need to be imagined and implemented. These things will not occur unless the law school takes the lead in spearheading them. On the finer level of specific strategies and actions, appraisals of the value and potential of each formation experience need to be conducted. What pedagogies can be introduced around each experience – before, during, and after it – to maximize its benefit? Who among the many, from the school’s faculty and staff to stakeholders and participants outside the school, are best situated to help the student maximize that experience, and in what way may they help? What formative assessment opportunities are presented by the experience? What developmental milestones, or assessments that might later be bundled into a summative assessment, might be involved?

2.2.3 Think about Curating and Coaching: Teaching Is Not Limited to the Transmission of Expert Knowledge

The stereotypical law professor is a “sage on the stage” who teaches students to “think like a lawyer” by mixing masterful Socratic dialogue with wisdom and expert knowledge. Today’s law professors know that the stereotype does not exhaust the pedagogic possibilities, and they should move beyond it when considering how to best support professional identity formation. Faculty who supervise students in clinical and practicum settings demonstrate the value of a “guide on the side” approach to teaching. That approach deserves the fullest exploration when supporting students in the formation of their professional identity (or, in the words of Carnegie’s Educating Lawyers, their third apprenticeship of professional identity and sense of purpose). Framing teaching in more traditional “knowledge transmission” terms limits the options and averts our eyes from the student’s experience.

What Dr. Robert Sternszus has said for medical education holds for law: “[T]he role of professional education should be to guide and support learners in the process of identity formation, rather than ensuring that learners understand medical [or legal] professionalism and demonstrate professional behaviors.”Footnote 25 Students need experiences as active participants in situations that signal the profession’s shared values, beliefs, and behaviors. They need encouragement to make the process of their identity formation their own and to reflect on the process as it unfolds. They need assistance in comprehending what they are going through.Footnote 26

This calls for teachers who can curate and coach. By curating, we mean staging the experiences and environments that will promote professional identity development, connecting them conceptually to one another in an intelligently sequenced fashion, and guiding students through them with a framework that helps the students understand their own development through the process.Footnote 27 With curating, students will experience their pre-professional-employment third apprenticeship much like a well-crafted interactive exhibit that purposefully raises and reinforces themes and meanings.Footnote 28 Coaching takes the guide on the side philosophy to the personal level, meeting students where they actually happen to be and providing assistance tailored to support the next step and capitalize on its developmental potential. As Dr. Yvonne Steinert explains:

Coaching is the thread that runs through the entire apprenticeship experience and involves helping individuals while they attempt to learn or perform a task. It includes directing learner attention, providing ongoing suggestions and feedback, structuring tasks and activities, and providing additional challenges or problems. Coaches explain activities in terms of the learners’ understanding and background knowledge, and they provide additional directions about how, when, and why to proceed; they also identify errors, misconceptions, or faulty reasoning in learners’ thinking and help to correct them. In situated learning environments, advice and guidance help students … to maximize use of their own cognitive resources and knowledge, an important component in becoming a professional.Footnote 29

Consider the implications when teaching includes curating and coaching. Curating makes the third apprenticeship coherent and knowable; faculty and staff can share an understanding of professional identity formation and the school’s strategy for its promotion. They then can see new possibilities for their own supportive participation in the effort. A contracts professor might turn to team-based exercises not just to spice up the teaching of doctrine and analysis but also to afford interactions that introduce the importance of collaboration when serving clients and the value to one’s own development of lifelong learning through engagement with other professionals. A professor might treat a seminar discussion of contemporary policy challenges as an occasion to coach on the role that lawyers play as thought leaders in their communities. Career services counselors might take their meetings with students about job searches as coaching interactions about the fundamentals of self-direction, self-awareness, and leadership-of-self.

The centrality of curating and coaching also points the way to doing assessment right in the professional identity formation area. Everyone who coaches or observes a student in a curated experience is positioned to offer potentially valuable feedback and information. Observers inside and outside the law school can provide formative assessments to benefit students in their development along one or another competency. Those assessments can form the basis for reflection and coaching, and they can be pooled and considered collectively to mark a student’s progress against milestones that reflect the stages of development envisioned for the competency.Footnote 30

In Chapter 4, we will have much more to say about student experiences that mark major transitions in a student’s development, the importance of coaching and how to deliver it in the law school environment, and how to approach assessments of professional development and formation goals.

2.2.4 Think Enterprise Wide: Professional Identity Formation Support Already Occurs throughout the Law School and Can Serve – Rather Than Detract from – Established Goals and Priorities

When law professors contemplate their school’s academic mission, they typically envision faculty as the educators and the school’s administration and staff in supporting roles. That view can be limiting when it comes to supporting professional identity formation. Formation is a socialization process; students develop through interactions and activities in contexts associated with the profession and its culture.Footnote 31 Because students have professional formation experiences throughout the law school, the school’s opportunities to support students in their formation run across the enterprise. No one who works at the law school lacks a potential role. Everyone can at least speak to and endorse the significance of professional identity formation in the same way that they do the values of thinking like a lawyer, doing like a lawyer, and striving for excellence. Most everyone can do more than that.

The idea that formation support is an enterprise-wide, “whole house” endeavor has significant implications. Formation-support work already is going on throughout the law school. Faculty do it when they lead critical inquiry in a traditional class, coach students about client counseling, teach ethics and professional responsibility classes that do not stop with the law of lawyering, require reflection exercises associated with externships, or advise students on law-reform projects in law school institutes or centers. Adjunct faculty members do it when they model how professionals strive to grow continually, achieve excellence, and serve others. When career-services counselors introduce students to the professional environments they might inhabit and coach them on how to gain entry to those worlds, they are supporting professional formation. Formation support also takes place in academic or student affairs (e.g., counseling and advising), academic support (e.g., time and stress management), and the admissions and financial aid offices (e.g., financial well-being programs).

The fact that formation work already is being done, and by so many, attests to its compatibility with a law school’s mission, priorities, and people. It also signals opportunities. By thinking enterprise wide, the law school will realize that improving its support of professional formation need not mean major new investments, redistributions of resources, or reordering of priorities. It is much more about working smarter – drawing on all of the school’s existing talents and resources (and tapping more outside, as alumni, practitioners, judges, government officials, the organized bar, and professional affiliation groups desire to see more attention paid to the values of professional formation and want to participate). Moreover, many features of a purposeful formation program are likely to be best practices for the pursuit of other law school goals and thus offer additional advantages to faculty and staff as well as students.

Let us pursue the point by reflecting more on the individuals who work in the law school and their varied perspectives, starting with common ground. All who work in the law school have reason to favor purposeful support of professional identity formation because it completes a holistic, professionally and morally satisfying picture of lawyer development and the school’s role in that development. The school increases the probability of student success when it attends more purposefully to student competencies that are fundamental to success – such as self-awareness, leadership-of-self, self-directed learning and development, emotional intelligence, and the effective navigation of professional environments. Student success, an unqualified good, is essential to institutional success – including healthy enrollment, reputation, alumni support, and philanthropic culture. Just ask any school that has suffered misfortunes on key measures of student success in passing the bar or securing meaningful employment.

At the level of individual self-interest, faculty and staff face differing circumstances and juggle different sets of priorities under different resource conditions. All, in their own stations and situations, can find advantage in purposeful support of identity formation.

Career Services and Academic Success Professionals. Law school colleagues working in the career services area have much to gain by implementing professional identity formation initiatives in their work with students. Student success in obtaining meaningful employment is a sine qua non of success in career services, and professionals in the area believe that student “ownership” of the search for employment is a critical ingredient. What is ownership but the exercise of fundamental competencies such as self-awareness, leadership-of-self, and self-directed learning and development, along with growing cultural competency and emotional intelligence?Footnote 32 Even a rudimentary career-services office engages in coaching and counseling directed at these competencies, and some now do professional identity formation work in earnest to better position students in the competitive marketplace and contribute to their wellness and capacity for self-care in a stressful profession.Footnote 33 Professional identity formation work in career services also can strengthen and leverage relationships with the bench and the bar and align the office with the legal profession’s trajectory toward competency-based professional development and evaluation.Footnote 34

Colleagues working in the academic success area can also perceive advantages in PD&F goals. Strong bar-passage outcomes are an established goal, and competencies such as student self-directedness, resourcefulness, resilience, and self-care figure in a successful journey to licensure.Footnote 35 Initiatives to help develop those competencies are well adapted to the coaching-rich environments typically found in academic success and career-services programs. Purposeful professional identity formation work seems destined for recognition in both areas as a best practice. Such work – especially when endorsed by faculty and administration colleagues – also signals that professionals in these areas are integral and valued co-educators in the law school’s program of legal education, enhancing their effectiveness and professional satisfaction.

Clinical Professors, Professors of Practice, Professors of Legal Research and Writing, and Externship Directors. Legal educators in clinics, practical skills courses, legal research and writing courses, and in-class components of externship programs see advantage in supporting professional identity formation. They have been doing it, if not in name, for some time now. Their educational objectives often include competencies such as teamwork and collaboration, client counseling, active listening, communication in varied contexts, giving and receiving feedback, and the management of ethical and moral tensions – building blocks of emotional intelligence, leadership, and the effective navigation of professional environments. These legal educators use guide on the side pedagogies, including coaching, feedback, and reflection. Best practices in the experiential learning and practical skills realms already feature ingredients fundamental to a program of purposeful support for professional identity formation.

Professors Teaching Doctrinal Courses. Professor Jerry Organ has depicted the situation in which professors who teach traditional doctrinal courses likely find themselves:

Some faculty members may be inclined to move forward under the professional identity flag, but may feel like they need some help because it is a different conception of their responsibilities as professors than how they have traditionally seen themselves. … They may see themselves more as being engaged in “knowledge transfer” and in helping students develop critical thinking skills – the hallmarks of “first apprenticeship” teaching. But they may also appreciate that the role of the lawyer as professional is distinctive and that students would benefit from having thought more about what it means to be a lawyer while they are gaining knowledge and sharpening their analytical skills.

These faculty members may require a little more direction. … They may need help to identity one or two concepts they could integrate into their classes without too much disruption. … They may need examples. … But with the right support, they likely will be willing to put more effort into adding professional identity formation in to their conception of their responsibilities as professors.Footnote 36

Professors may be congenial to more purposeful formation support but uncertain of what it would entail in their own work and hence unready to proceed themselves. They need to be introduced to the possibilities and hear from peers who have positive experiences to share. One of the coauthors, Professor Bilionis, has incorporated purposeful support of professional identity formation into a basic first-semester, first-year course, and the results have been gratifying. It is a constitutional law class, and students are asked to concentrate on teamwork, collaboration, and the giving and receiving of feedback – all in service of a learning outcome directed to the student’s ability to “participate as a member of a professional community whose members work individually and together to continuously improve their capacities to serve clients and society.”Footnote 37 While developing professional identity formation competencies, students support one another in their learning of doctrine and sharpening of analytical and critical capacities. They report that the method helps their learning, increases their confidence, and leads them to a greater appreciation of diverse viewpoints in the law. For the professor, introducing formation support explicitly establishes the student-professor relationship on broader, more satisfying ground. Empathy, trust, and support enter the picture, at no cost to analytical rigor and the transfer of knowledge. Bringing that more inclusive framework to life in the classroom invigorates the learning environment.Footnote 38

Some professors teaching traditional subjects may conclude that their own time and talents are best focused exclusively on the cognitive and doctrinal objectives of their course. They will still have reason to support enterprise-wide efforts toward student professional identity formation, for they benefit from their students’ and institution’s gains. They can endorse the efforts of others and validate them for students – a practice that enthusiasts of professional formation work sometimes call “cross-selling.”

Associate Deans. Associate deans with academic affairs or student affairs portfolios (we can treat them here as combined for simplicity’s sake) should perceive advantage in the law school’s purposeful support of professional identity formation. Their charge is to deliver a sound, competitively well-positioned program of legal education that prepares students for their futures, enriches their formative opportunities, secures their success in bar passage and employment, attends to their wellness, and meets obligations and expectations set by constituencies of consequence (including accreditors; licensing authorities; and, except for independent stand-alone schools, university leadership). The law school’s collective, purposeful support of professional identity formation contributes directly to meeting that charge.

The benefits to students, faculty, and staff we have noted bear positively on the associate dean’s agenda and can be consolidated into terms conducive to the associate dean’s perspective. Law schools have a “hidden curriculum” – acts of omission and commission within the school that can signal meanings different from, and even at odds with, the school’s formal representations. American legal education’s traditional emphasis on critical thinking and analysis, combined with relatively slight attention to matters of professional identity formation, has produced a hidden curriculum that privileges cognitive prowess to an extreme and to the detriment of other essential professional attributes.Footnote 39 A purposeful, enterprise-wide formation support program counteracts that hidden curriculum, placing the three apprenticeships on par with one another and increasing the effectiveness of formation-oriented initiatives already underway. Adding to those initiatives in purposeful ways can better equip students to be engaged and capable learners, job seekers, and successful takers of the bar examination. It also helps them develop resilience and resourcefulness, valuable attributes for managing professional life. Students can make more for themselves of law school and the opportunities and resources it offers.

There are additional benefits for the associate dean that are less apparent to faculty, students, and fellow administrators. When the law school establishes purposeful support of professional identity formation as a component of its educational program, it opens for use a new array of concepts, competencies, and pedagogies that can help rationalize management of the curriculum and the allocation of resources. Purposeful support of professional identity formation leads to more detailed attention to professional competencies, putting the school on a path of alignment with competency-based education, the model that accreditors and university leaders increasingly favor.

The Dean of the Law School. The foregoing advantages of purposeful support of professional identity will weigh no less favorably to the dean, who should see positive, student-centered educational reform as an answer to a long-lingering challenge. The dean also may well appreciate the flexibility that such an initiative affords. Significant progress can be achieved within the framework of the traditional law school and its political economy, efficiently and with no meaningful disturbance. Should the school adopt a competency-based model, in whole or in part, its formation efforts will translate easily.

Thinking more broadly, the dean may recognize that reform here places the school, as an institution, on securer footing for the present and future. How so? A program of purposeful formation puts to fuller and more efficient use resources already possessed by the school internally and within its reach externally. It posits that faculty and staff members are collaborators and that effective professional identity formation work is an enterprise-wide affair – thereby setting a stage where cooperation, communication, and coordination across the enterprise can be practiced constructively. It also provides a basis for integrating external stakeholders more rationally in the law school’s mission. Consciously coordinated work on common ground is bound to strengthen relations that are vital to the school’s success now and in years to come.

The dean also should perceive advantageous implications for the school’s mission and identity. Embracing professional identity formation does not contest the importance of the first or second apprenticeships of legal education; it honors them with a galvanizing third apprenticeship. It does not question in any way the school’s commitment to and investment in research; no meaningful redistribution of resources is involved, and the move has been made in medical education without adverse incident. What initiative here offers, when all is said and done, is unthreatening innovation that strengthens legal education’s claim to authenticity. The American law school’s mission rests on the importance to civil society of law and its practice, and the conviction that law must be the subject of disciplined academic study and effective professional training. A law school applying its best efforts to pursue that mission would adopt purposeful support of professional identity formation as a clear improvement over the status quo ante.

2.3 How to Advance the Law School’s Own Professional Development

To successfully bring purposefulness to its support of students, the law school needs to be purposeful about its own development. Here are some recommendations.

2.3.1 Support the Law School’s Own Professional Development

A lot has happened in and to American legal education in recent years. Economics and technology have begun to appreciably reshape the demand for legal services and the legal profession that provides them.Footnote 40 A major economic recession and a pandemic have made it significantly harder for students to obtain meaningful employment, and the law school’s responsibility for the success of its graduates in the employment market has heightened. Law school enrollments have declined. Competency-based education has knocked on the door in the company of accreditation reform. Distance learning has arrived.

In the matter of the third apprenticeship and professional identity formation, much has occurred as well. When we talk today about professional formation, we talk differently from how we did when Educating Lawyers was a fresh read. Research and thinking about how to support law students in the formation of professional identity have advanced. Medical education, meanwhile, has taken professional identity support to new frontiers, expanding the range of considerations and possibilities. New ideas, theories, themes, and vocabulary continue to enter the discussion.

To absorb it all requires claims on the law school’s adaptability and capacities. The best advice to law schools is to follow the same advice they would give to a similarly situated developing lawyer: tend consciously and resourcefully to your developmental needs. Faculty and staff need to come up to speed before they can move ahead efficiently and effectively, and a plan to make that happen should be devised.Footnote 41 No school needs to reinvent the wheel. A network of educators who focus on professional formation is available to help, with the Holloran Center at the University of St. Thomas School of Law serving to grow, nurture, and support that network. The Association of American Law Schools and the National Association for Law Placement now offer programming on professional identity formation, following the lead of several organizations serving sectors and affinity groups within legal education.

2.3.2 Be Purposeful in Project Management

Institutions rarely have latitude to wait on change until every angle is worked out. Bringing purposefulness to a law school’s support of professional formation will be its own case of stage development, with many specifications of a full-fledged program to be determined later.

The law school’s project management competencies will be pressed here. The goal is a curated program that spans the pre-professional-employment period of a student’s development; the challenge is to divide its creation into manageable projects that the school can sequence appropriately and with timely support. Some projects will stand out for fast-track work because they concern inevitable components of a solid program and represent low-hanging fruit from a resource standpoint. Enriching the career services environment to include coaching and support on self-direction, self-awareness, and leadership-of-self falls into this category. The same may be said for remodeling the school’s orientation program to introduce experiences for first-year students that highlight professional identity formation as fundamental to their legal education. Revamping how the school communicates its vision of legal education – formally and in the hidden curriculum – to ensure that the third apprenticeship holds an importance equivalent to the first and second might be another early item.

A second group of projects will merit early action because an immediate leveraging opportunity presents itself. The requirement to comply with new accreditation standards, for instance, makes now the right time to establish learning outcomes linked to professional identity formation at both the law school program level and the course-specific level.

A third set of projects will feature a pace that varies with increments. These are initiatives that are advisable to begin because they are critical to the goal but involve matters about which we have much to learn – and thus warrant an iterative development process or treatment as representative experimental pilot programs.Footnote 42 Efforts to inventory the influential periods of transition that students experience, learn what makes them so, and map them to competencies might fall into this category. Devising stage development rubrics for those competencies and fashioning a comprehensive assessment model deserve similar recognition.

2.3.3 Nurture Relationships and Collaborations

A fully realized third apprenticeship would span the pre-professional-employment period of a student’s development as a lawyer, curating experiences inside and outside the law school, enriched by coaching, reflection, and other pedagogies. Students would interact with a broad array of professionals who, in addition to aligning the environment with the legal profession, serve as role models, mentors, coaches, and providers of feedback. If the competency-based education model is adopted, formative assessments from those participants would culminate in summative assessments of the student’s progress against competency milestones rooted in well-conceived models of stage development. As best it can with the significantly more limited resources that it enjoys, legal education will have created its counterpart to medical education’s apprenticeship of professional identity formation.

Meaningful progress toward that vision could be enough to bring about a true transformation of legal education. Pursuing that vision necessitates that the law school stretch another set of its core professional competencies – its ability to form fruitful relationships, collaborations, and teams, and to work across differences. Old hierarchies within the law school can be relaxed without fear in favor of an enterprise-wide commitment to student success that unites faculty and staff in teamwork. Old distinctions between the law school and the legal profession, between the so-called ivory tower and the so-called real world, can be transcended in favor of a vision of student development that takes place in a supportive pre-professional-employment environment where diverse stakeholders are partners in the profession. These things can happen, but only if they are pursued with conscious purpose.

2.3.4 Understand Lessons Learned from Medical Education

Earlier discussion in this chapter emphasized that a law school can improve its support of each student’s professional identity formation and realize the benefits listed in Chapter 1 in a gradual step-by-step approach without going “all in” on competency-based education. This gradual step-by-step approach nonetheless can benefit from the lessons learned in medical education’s move toward competency-based education starting in 1999, fifteen years before the ABA changed the accreditation requirements for law schools to require learning outcomes and program assessment. In the next chapter, we explore what we can learn from medical education’s experience.