I am the current holder of the Royall Chair at Harvard Law School (HLS). I inhabit a troubled brand. This chapter tells a story of a mark associated with it: a heraldic shield with three gold wheat sheaves on a field of blue (Figure 9.1). The vicissitudes of this mark, going on 300 years old, demonstrate how even a long-lived and much-valued brand can fall to the winds of reputational change; and how even a devastated brand can recover its lustre when those winds change course. Looking it all over, I am struck by the stubbornness of symbolic value as much as I am by its frailty in the face of political and moral contestation.

Figure 9.1 Royall family shield with crest.

For me, the story starts with my becoming eligible for a Chair, through sheer seniority, in 2006. I had come over from Stanford Law School in 2000, and there was a lot about my new local academic culture that escaped me. There are no monetary or other upsides of a Chair designation to the faculty member, and the only expectation it entails is the delivery of an inaugural “Chair lecture.” But still, getting so senior that you qualify for a Chair is not nothing. I noticed that a number of the Law School’s oldest Chairs were empty, and I called up Dean Elena Kagan (who served in this capacity from 2003 to 2010) with a simple request: “Give me an old one.” She took it under consideration, and that was the end of our conversation.

At the year-end faculty lunch where the new Chairs are announced, Dean Kagan announced that I was the new Royall Chair. A gasp went around the room. Why? I was completely in the dark.

Soon afterwards, I learned that I had a tiger by the tail. Daniel R. Coquillette, who was co-writing the unofficial history of the Law School together with Bruce A. Kimball,Footnote 1 graciously provided me with all his files on Isaac Royall, Jr., the donor of the Chair. His research assistant at the time, Elizabeth Kamali – now a tenured colleague on the faculty – helped me figure out the old documents.

What I learned from these files astonished me. This donor had come with his father and family to New England from Antigua in 1737, where they had owned multiple sugar plantations and held dozens of human beings in bondage. They traded in sugar and slaves as part of the Triangle Trade. In 1734 alone, Isaac Royall, Sr. sold 121 human beings.Footnote 2 After a drought and an earthquake, followed by a panic over a slave uprising and its severe repression, the family left Antigua for New England, settling in Medford, a town very close to Cambridge. They brought a large number of enslaved persons to their large Medford estate and proceeded to farm the land and live like the 1 percent of their era. Their large slaveholding was unusual in New England: essentially, they pared down the sugar plantation model of slaveholding and transposed it onto the more household-based New England slave/indentured-labor landscape.

When Isaac Royall, Sr. died in 1739, Isaac Royall, Jr. stepped into his father’s life. Today we can tour the grand Georgian home he and his family inhabited on the banks of the Medford River; it is now run as the Royall House and Slave Quarters and curated to enable a deep comparison of the lifeways of the white Royalls and the people they held as slave labor (Figure 9.2). The site includes the large and well-preserved and probably only surviving slave quarters in New England. The Royall House and Slave Quarters Board commissioned Alexandra Chan to do an archaeological study of the latter, which yielded considerable information unattainable from the written record.Footnote 3

Figure 9.2 Royall House and Slave Quarters.

Isaac Royall, Jr. fled to London at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, and wrote his final will there.Footnote 4 It had two provisions that continue to provoke interest. In one, he made a grant to Harvard College to establish a “Professor of Laws … or … Professor of Physick & Anatomy” (what we would call medicine) (Item 12, Codicil Item 5). This is the Chair I now hold. And secondly, he provided for a single one of his enslaved human beings, Belinda, the option of freedom or becoming the personal property of his daughter, and stipulated (as the law of Massachusetts then required) that if she chose her freedom, she would not become a charge upon the town of Medford (Item 5). This implied that his estate would provide her with maintenance, if needed, to prevent her from becoming so needy that the town would be obliged under the Poor Law to support her, but the will made no explicit provision for her support.

Isaac Royall, Jr. had no income of which we are aware that was not directly or indirectly derived from slave labor. In light of this whole story, it’s no exaggeration to say that the commencement of legal education at Harvard was enabled by the large-scale exploitation of black slaves. Symbolically, the link from that money to HLS was my Chair.

For my 2006 Chair lecture, I stood beneath the Robert Feke portrait of Isaac Royall, Jr., his wife, their daughter, his sister, and his wife’s sister in the Treasure Room in Langdell Library (Figure 9.3)Footnote 5 – now named for a donor, the Caspersen Room – and told his story as best as I could figure it out. I published the lecture soon afterwards in the Harvard BlackLetter Law Journal.Footnote 6 What Coquillette and Kamali did was an amazing act of scholarly generosity: Coquillette let me scoop him on his own research, and Kamali helped him do it.

Figure 9.3 Robert Feke, “Isaac Royall and Family.”

As Coquillette and Kimball explain in the first volume of their history of HLS, On the Battlefield of Merit: Harvard Law School, the First Century, the Royall Chair did not automatically lead to the establishment of the Law School. Rather, the original idea was that the Royall Professor would give a lecture series on law to students in the College. This embodied a new theory of legal education: not apprenticeship in a lawyer’s office but the study of legal science equivalent to philosophy and theology as knowledge systems fit for instruction to undergraduates. But when they finally got underway in 1815, the endowment barely yielded enough to pay Isaac Parker, Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, for part-time work at Harvard. Throughout his service, his primary responsibilities were as a judge. A two-stage, lurching process led to the establishment of a viable Law School. Stage one, beginning in 1817, added a tuition-funded professor, Ashael Stearns, and inaugurated the Law School proper.Footnote 7 Yet stability and growth were out of reach for this tiny, overburdened faculty; it was not until 1829, when Nathan Dane and Joseph Story orchestrated the Dane Professorship with a significant endowment – and Story as its first occupant – that the Law School faculty could grow to three professors with a comprehensive curriculum and a stable business model.Footnote 8 Coquillette and Kimball exaggerate by quite a bit when they designate Isaac Royall, Jr. as the “founder” of Harvard Law School.Footnote 9 By their own account, that role went to Parker, Story, and Dane. But the Royall Chair was the spark that started Harvard out in its commitment to legal education. It remains the Law School’s oldest Chair. That is my Chair. What does it mean? A lot of different things, it turns out.

Isaac Royall, Jr.

In his final will, Isaac Royall, Jr. directed that the vicinity of his house in Medford be called Royall Ville “always” and that anyone who inherited this entailed estate must take Royall as his last name (Items 21 and 22). He was a man obsessed with promoting and celebrating himself as a brand, specifically as the patriarchal, slaveholding, faux-aristocratic social capital of which he was the human embodiment.

His marks were many. The Feke portrait of him as paterfamilias, the John Singleton Copley portrait of his daughters festooned with luxury clothes and toys, the paired Copley portraits of Isaac, Jr. and his wife,Footnote 10 and the Royall House and Slave Quarters themselves: all survive to us as marks of his brand. But the most literal sign of his identity is the heraldic shield that he and his father adopted as their family crest.

A brief introduction to British heraldry is in order. In British usage, a shield or “coat of arms” is granted by the Crown – and by the Crown only – as a mark of honor and for the exclusive use of the grantee, who may be a knight or aristocrat, an individual who has accomplished something the Crown wishes to reward, a unit of government, or an institution. When granted to a human being, and as befits its character as a mark of royal or aristocratic status, it’s heritable. It is explicitly honorific, and when used by non-royal individuals along the line of descent, it signifies aristocratic status, notable achievement, or royal favor belonging to the original grantee.

These marks frequently take the shape of a martial shield in reference to the idea that in the British tradition, which vastly predominated in colonial New England, the very first such arms were actual shields carried by aristocratic or knightly warriors into actual battle, and are called coats of arms because warriors would wear heraldic devices on coats worn over their armor. It’s called heraldry because, in premodern usage, heralds combed the countryside for family births and deaths and granted shields. The entire system involves an elaborate history and detailed technical know-how. Each coat of arms is a state-sponsored, state-designed, state-bestowed mark, deliberately held scarce to the point of being unique, intended to enhance the status – the brand – of its bearer.

In the special language of heraldry, the verbal description of the Royall family shield (its “blazon”) is “azure three garbs 2 and 1 or,”Footnote 11 that is, three wheat sheaves with one centered for a top row and two more below it in a second row, in gold on a background of azure. Surprisingly, we know a lot about how it was used by the Royall family. It appears on silver vessels given to churches attended by Isaac Royall, Jr. and his family, on a tomb erected in Dorchester to memorialize the grandfather and father, on bottles, bookplates, and wax sealsFootnote 12 – and that’s just what remains after more than 300 years! Isaac Royall, Jr. and his father clearly engaged in an extravaganza display of the shield.

Correspondence with a Windsor Herald in the British College of Arms confirms that the Royall arms “appear to be those of the medieval Earls of Chester.”Footnote 13 In heraldic lingo, this means that the Royall family shield was assumed or assumptive, and not invented but pirated (more heraldry-speak) from arms authentically borne by an ancient aristocratic family.Footnote 14 That is to say, the Royall shield is not only fake but also stolen.

There is certainly nothing aristocratic about the Royall family. The grandfather, William Ryall, and another man emigrated to New England in 1629 as indentured servants to work as “coopers and cleavors of tymber.”Footnote 15 He first settled in Salem, and gave his name to a section of the newly settled town: “Ryal Side.”Footnote 16 Once free, he moved to Maine,Footnote 17 where according to some sources he gave his name to a river along which he owned land.Footnote 18 He died in North Yarmouth, Maine.Footnote 19 The name is recorded as Ryall, Ryal, and Rial before it was converted to the more pretentious Royal and Royall.Footnote 20 At the apex of the family’s prosperity, they were agricultural magnates and traders, including active participation in the slave trade. At the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford you can still see the wooden statue that Isaac Royall, Jr. placed in the center of his formal garden. It is of Mercury, the god of trade, an emblem I take as a warrant to claim that Isaac Royall, Jr. was himself not the least bit ashamed of his commercial success, and that he, at least, felt he had no nobility to lose.

Charles Knowles Bolton, one of the primary sources on American heraldic practices, traces the Royall shield back to the grandfather.Footnote 21 This is unlikely. The above-mentioned bookplate is surely attributable to Isaac Royall, Sr. and corresponds with a large library, twelve times larger than that of any other Boston household inventoried in the decade of his death.Footnote 22 The church silver dates to Isaac Royall, Jr.’s time, and Chan excavated the bottles decorated with the device from the Medford home, first owned by Isaac Royall, Sr. This is not an ancestral mark: father and son used it to dignify new money.

What would it have meant to the contemporaries of the Royall father and son that they lavishly displayed the shield? There was never a College of Arms in any of the North American British colonies. The Constitution includes clauses barring ranks of nobility,Footnote 23 and the founders rejected the idea of establishing a national College of Arms.Footnote 24 Heraldry bore a strong anti-republican stigma. But it was permitted, tolerated, and in widespread use. Very seldom did colonial arms-bearers show authentic arms. Far more often they assumed arms to which they had no home-country right.

Indeed, what made heraldry controversial in the revolutionary period and early republic was any claim that it should be made authentic by the establishment of an American College of Arms. The following story is indicative. On July 4, 1776, the same day that the Declaration of Independence was issued, the new nation’s leadership authorized the creation of a national seal.Footnote 25 A state seal would symbolize the country’s full independence and its equality with other seal-bearing states of the world. As a mark, a state seal is far from the heraldic shield of an aristocratic or merely rich family. The state seal is given to the control of an authorized officer, who must apply it to certain official documents for them to be valid; it played an important role in international diplomacy, particularly in the recognition of states by other states as formal co-equals. The US could adopt a state seal without implying anything about establishing a College of Arms issuing family shields in America.

But in 1788, William Barton, who had already contributed the eagle to the design of the Great Seal of the United States (which was not finally promulgated until 1782),Footnote 26 wrote to George Washington urging the establishment of state-authenticated heraldry:

I have endeavoured, in my little tract, to obviate the prejudice which might arise in some minds, against Heraldry, as it may be supposed to favor the introduction of an improper distinction of ranks. The plan has, I am sure, no such tendency; but it is founded on principles consonant to the purest spirit of Republicanism and our newly proposed Fœderal Constitution. I am conscious of no intention to facilitate the setting up of any thing like an order of Nobility, in this my native Land[.]Footnote 27

Washington himself made prolific use of ancestral arms, probably brought to America by his great-grandfather, and cared enough about their authenticity to obtain ratification from the College of Arms in 1791.Footnote 28 But setting up a College of Arms in the United States was a bridge too far. He gently rejected Barton’s argument that heraldry could harmonize with life in a republic of juridical equals. Washington’s diplomatically stated response declares that he was chary of introducing official heraldry not because he deprecated it, but solely because the political moment was too inflamed to risk even an innocent move that could enable the opponents to denounce “the proposed general government … [as] pregnant with the seeds of distinction, discrimination, oligarchy and despotism[.]”Footnote 29

Thus authentic arms were extremely rare and highly prized, but derived from a remote and contested sovereign; assumed coats of arms were ubiquitous and unregulated; and heraldry signified social rank, even aristocratic family origins, in a society committed both to social hierarchy and to legal equality for white men. In these circumstances, what would people make of a shield like the Royalls’? Much later, heraldry and genealogy aficionados earnestly heaped contempt on assumed arms.Footnote 30 But these strenuous efforts all have an antiquarian feel to them: it would be a mistake to read them back onto the colonial cultural milieu. At the time the Royall family was brandishing its shield, the distant past that these later strivers were trying to preserve was the common present. Rules and rolls separating authentic wheat from assumed chaff would have been unnecessary where the very few who had authentic arms would have been known to do so. Isaac Royall, Jr.’s use of his faux-ancestral shield could have indicated some fondness for the aristocratic hierarchy of the homeland or sympathy with colonial officialdom; but its ersatz origins could equally have signaled disrespect for colonial pretensions to aristocratic status. With his flight at the outbreak of the Revolution, it might have been used as part of the case against his loyalty to the new government – but it would not do to take that line of thought too far. According to the American Heraldry Society, thirty-five signatories of the Declaration of Independence, including John Hancock and Benjamin Franklin, were armigerous;Footnote 31 even John Quincy Adams bore assumed arms.Footnote 32

Fittingly, perhaps, the very issue of revolutionary fervor for a government dedicated to freedom and equality – to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and to the proposition that all men are created equal – had a direct, personal impact on Isaac Royall, Jr., in the form of a precipitous fall from political grace. The revolutionaries’ rapid victory in the Battles of Concord and Lexington on April 19, 1775, switched out the governing powers in eastern Massachusetts overnight. Isaac Royall, Jr. had gone to Boston three days earlier, separating himself from the patriot-controlled countryside and lodging in an urban, armed camp controlled, at King George’s command, by General Gage.Footnote 33 Did his travelling to Boston at that moment suggest loyalty to the Crown (the thinking would run: “Royall was with the Royalists so he must be one”) or was he on an anxious mission to repair bridges to the British after his bold refusal of the oath to become a Mandamus Councilor as part of George III’s plan for repression of the colonists?Footnote 34 Close reading of his political engagements before this crisis suggests that he preferred a mediating role between the increasingly alienated extremes;Footnote 35 on April 19, 1775, the space for such political ambivalence shrank to the vanishing point. Even if his trip to Boston were entirely innocent of political intentions, it could not now be unmarked by political signification. But the polarization of the semiotic field and the emptiness of his sign produce an ambiguity that will probably never be resolved.

Nor did his subsequent actions bestow a clear meaning on his travel to, and his subsequent flight from, Boston. Within days of the opening of the Revolutionary War, he fled in the general evacuation of loyalist civilians from Boston, landing in Halifax. About a year later, he proceeded to London.Footnote 36 When seeking to ingratiate himself with the British aristocracy and to obtain a share of the monetary support being doled out to loyalists forced into exile by the Revolution, he represented himself as “one of the unfortunate persons who from the dreadful tempest of the times in the Massachusetts Bay was obliged to leave that country and finally take refuge in this[.]”Footnote 37 But when seeking to ingratiate himself with Massachusetts elites he explained his trip from Medford to Boston as the first stage of a voyage to Antigua to settle some financial matters, his trip to Halifax as an effort to gain a safe harbor whence to complete his trip to Antigua, and his decision to shift to London instead as a concession to his desperate family, who had already settled there. How else could he see his grandchildren, he pathetically asked.Footnote 38 In the former letter, he denounced the “Colonists” as “deluded” and unable to see that their “true interest” lay in “their duty to their Mother Country and to the best of Kings”; in the second letter he professed loyalty to the new Commonwealth. If in controversies over his character centuries later Isaac Royall, Jr. has been subject to radically divergent interpretation – the dizzying oscillation that this chapter traces – it is perhaps safe to say that it began in his own acts of self-branding.

This calamitous bouleversement was family-wide. Isaac Royall, Jr. and his sons-in-law Sir William Pepperell and George Erving were named in the Banishment Act of 1778; the latter two were also named in the Conspirator’s Act of 1779 and thereby lost all their Massachusetts holdings; the Massachusetts property of Isaac Royall, Jr. was seized under the Absentee Act of 1779 and was returned to his estate only near the end of the century.Footnote 39 These seizures included personal as well as real property. And having left Massachusetts after April 19, 1775 and “join[ed] the enemy,” they were all subject to the Test Act of 1778, proscribing their return.Footnote 40 The only reason that their exile was not spent in complete destitution was the continued enjoyment of their West Indian holdings and any assets they had managed to extract from North America prior to restrictions being imposed by the loyalty acts.Footnote 41

From its very first day, the Revolutionary War and its eventual turning-upside-down of political control crashed the Royall brand. Two subsequent stories, one involving his bequest to Belinda, the other involving his bequest to Harvard College, show how temporary this nadir was.

Belinda Sutton

After Isaac Royall, Jr. died in 1781, Belinda took her freedom and triggered his estate’s legal duty to support her if she were in need.Footnote 42 Starting only two years later, she filed six petitions – in 1783, 1785, 1787, 1788, 1790, and 1793Footnote 43 – with the Massachusetts Legislature, sitting as the General Court, seeking that support. Belinda signed all these petitions with “her mark,” an X, a reliable indicator that she was illiterate and could not have written them herself. In response to the first petition, the General Court ordered that fifteen pounds, twelve shillings be paid to her annually from the Commonwealth Treasury.Footnote 44 The fair copy of this “resolve” was signed by John Hancock and Sam Adams.Footnote 45 The next two petitions complained that payments had stopped after one annual cycle; Belinda’s petition of 1793 indicates that only one further payment had been made, in 1787; and in 1790 she sought payment from the estate of a promised ten shillings per week for life. In 1788 and 1793 she signed as Belinda Sutton; apparently she had married. The latter petition was witnessed by Priscilla Sutton: was this the infirm daughter Belinda mentioned in her first petition? In 1793, Belinda alleged that she had sought recourse to Isaac Royall’s son-in-law, Sir William Pepperell, and that he “made her some allowances, but now refuses to allow her any more[,]” causing her to seek once again the original “bounty.”

As the years go by, the petitions become increasingly desperate, speaking of her old age, inability to work, and poverty. And indeed, she would have been very old: she indicated in the first petition that she was seventy years old, so by the time of the last one she would have been about eighty-three. There is a crescendo of misery: Belinda spoke of “her distress and poverty” (1785); averred herself “thro’ age & infirmity unable to support herself” (1787); and complained that she was “perishing for the necessaries of life” (1790).

The nearly perfect failure of the Treasury to follow the 1783 order, despite dramatic signatory support from Hancock and Adams and continually renewed petitions from Belinda, has the earmarks of back-channel controversy: someone or some ones inside government was or were putting themselves in the way. Who was responsible for Belinda’s suffering?

The first petition blames Isaac Royall, Jr., the exploitation of slavery, and the hypocrisy of the revolutionary elite. It is an indictment of the man precisely for his role in enslaving human beings. The petition links his tyranny over Belinda to his affinity for British tyranny: Belinda denounces them both and shames the Legislature for seeking freedom for white colonists but not black slaves.Footnote 46 This was the first time – and, as far as I know the last time, until the Royall House and Slave Quarters leadership and then Coquillette took up the issue – that Isaac Royall, Jr. was in any way held to account as a slaveholder. This singeing document appealed to the wartimeFootnote 47 legislature of Massachusetts – a body of men who had staked all on independence from Britain – by praising them for their commitment to freedom and equality for all, and then shaming them for not extending succor to a victim of slavery and oppression much worse than anything they had suffered at the hands of Britain. It pointed the finger of hypocrisy directly at them, and gave them a handy exit from moral opprobrium: relieve Belinda’s need.

The petition begins with an idyllic account of Belinda’s birth and childhood on the African Gold Coast. It then tells of her seizure by white slave traders, of the misery she endured on what we call the Middle Passage, and of her shock when she arrived in America to find herself in a Babel of strange tongues and in slavery till death. Then she made her appeal for justice, which is worth quoting in full:

Fifty years her faithful hands have been compelled to ignoble servitude for the benefit of an ISAAC ROYALL, untill, as if Nations must be agitated, and the world convulsed for the preservation of that freedom which the Almighty Father intended for all the human Race, the present war was Commenced – The terror of men armed in the Cause of freedom, compelled her master to fly – and to breathe away his Life in a Land, where, Lawless domination sits enthroned – pouring bloody outrage and cruelty on all who dare to be free.

The face of your Petitioner, is now marked with the furrows of time, and her frame feebly bending under the oppression of years, while she, by the Laws of the Land, is denied the enjoyment of one morsel of that immense wealth, apart whereof hath been accumilated [sic] by her own industry, and the whole augmented by her servitude.

WHEREFORE, casting herself at the feet of your honours, as to a body of men, formed for the extirpation of vassalage, for the reward of Virtue, and the just return of honest industry – she prays, that such allowance may be made her out of the estate of Colonel Royall, as will prevent her and her more infirm daughter from misery in the greatest extreme, and scatter comfort over the short and downward path of their Lives – and she will ever Pray.

Boston 14th February 1783 the mark of Belinda

Note that when the petition names Isaac Royall in its first sentence, it shifts to a strikingly larger script, exaggerating the pun involved in his last name: even Isaac Royall’s name condemns him.

Roy E. Finkenbine tells the story of this petition’s publication by revolutionary-era critics of slavery.Footnote 48 Whoever wrote it – probably Prince Hall, a member of the politically and culturally active free black community of BostonFootnote 49 – intended, and got, an audience wider than the Massachusetts Legislature. Belinda’s first petition thus marks a second nadir for the Isaac Royall brand.

After wrangling with the records, I can explain how but not why Belinda was subjected to such prolonged deprivation of the support due to her. If Royall had not fled Medford, if his estate, once in probate, had remained under his executor’s control, and if Belinda, once freed, became (as she did) unable to support herself, the Poor Law overseer of Belinda’s town could have brought suit against the estate for emancipating Belinda without providing security. But Royall’s estate was under the control of the state, though it never escheated. Ironically, it was Royall’s fall from grace as an absentee that made it possible for as-yet unidentified forces in the colonial and then new Commonwealth government to choke off her support. Only when Isaac Royall was relieved of that opprobrium were funds returned to the control of his executor.

The story of this gradual re-rise of Isaac Royall is a law story.Footnote 50 On May 25, 1778, the Town of Medford placed Royall’s estate in probate, with Simon Tufts as agent.Footnote 51 The Selectmen based this move on the fact that “the said Isaac Royall voluntarily went to our enemies and is still absent from his habitation and without the State.”Footnote 52 Two years later, the Massachusetts Legislature adopted the Absentee Act. A letter from Tufts dated May 26, 1780 indicates that he and Willis Hall (to be distinguished from Prince Hall, the probable drafter of the first petition), already named executor under Royall’s will, petitioned together for release of the estate, but that “the Court … have … Hung it up”Footnote 53 – that is, opted for inaction with the result that the estate remained in state hands.

Royall died in 1781. Belinda’s first petition resulted in the 1783 General Court order on her behalf, which directed: “That their [sic] be paid out of the Treasury of this Commonwealth out of the rents and profits arising from the estate of the late Isaac Royall esq an absentee fifteen pounds twelve shillings p[er] annum[.]” The Absentee Act had moved the funds into the Commonwealth Treasury. The verso of the original order includes calculations of the recent income to the Treasury from Royall’s property. There were sufficient funds to pay Belinda her due.

Isaac Royall, Jr.’s will was entered in probate in 1786, empowering Willis Hall to serve as his executor.Footnote 54 On February 28, 1787, Hall registered a list of Royall’s legacies and debts in the Suffolk County Probate Court. The debts included “for support of Belinda his aged Negro servant per annum for 3 years ₤30.”Footnote 55 This roughly corresponds with the Treasury’s then-unpaid support allowances for 1784, 1785, and 1786 (shaving off twelve shillings). Hall apparently had control of some assets, but in the 1790 petition Belinda (that is, probably, Willis Hall) indicated that “the Executor of [Isaac Royall’s] … will doubts whether he can pay the said sum without afurther [sic] interposition of the General Court[.]” So Hall took Belinda’s cause to the General Court: he witnessed and probably wrote the 1787 and 1793 petitions, and likely had at least a guiding hand in those of 1788 and 1789.

It is very possible that Willis Hall believed that, in petitioning for Belinda’s relief, he was pursuing his principal’s intentions. From a contemporary perspective, this is not entirely exonerating. Isaac Royall’s will bequeathed four enslaved human beings – “my Negro Boy Joseph & my Negro Girl Priscilla” to “my beloved Son in Law Sir William Pepperell Baronet” (Item 4) and “my Negro Girl Barsheba & her sister Nanny” to his daughter, Mary Erving (Items 5) – and Hall may have executed those instructions. Nor is it clear why both Royall and Hall were so committed to relatively favorable treatment of Belinda Sutton. But I think it is evident that, even after the abandonment of the fiercely political strategy embodied by the first petition, Mrs. Sutton was not without friends.

The stakes for Belinda of Isaac Royall, Jr.’s flight to London were therefore very high. Willis Hall was clearly dedicated to her support. If Royall had not fled, and had been able to appoint Hall his executor, Hall would have had not only the inclination but also the power to pay for her support. But because of Royall’s flight, his estate was locked up in the Commonwealth Treasury for most of her time as a free woman.

Two years after Isaac Royall, Jr. died in London, Britain and the United States concluded a peace. After independence, anti-loyalist confiscations continually lost ground, a process that indirectly improved Royall’s reputation. The Treaty of Paris (1783) nominally committed Congress to urge the states to restore property they had confiscated under their loyalty statutes.Footnote 56 David Edward Maas shows in detail the ever-so-gradual success of Massachusetts absentees in regaining legal capacity between 1784 and 1790: permissions to possess and inherit, to collect debts, and to return were gradually granted to the lucky few, with an equally gradual diminuendo of anti-loyalist vitriol and controversy.Footnote 57 Harvard started receiving land granted to it by Royall in 1795/96.Footnote 58 And in 1805, the General Court issued a resolve allowing Royall’s loyalist heirs to convey property that they inherited under his will.Footnote 59

Belinda’s 1788 and 1790 petitions designated the man she had denounced in her first petition as “the honorable Isaac Royall.” Her petitions were now in the hands of Willis Hall, not Prince Hall: she may have still felt intense scorn for her former owner, but expressing it was no longer an option. Between 1793, the year of Belinda’s last petition, and a 1799 petition filed by successors to Hall acting as executors of the Royall estate – thus roughly in the same period during which Harvard started taking possession of its Royall land bequests and well before his loyalist heirs were allowed to step into their inheritance – a settlement was reached securing support for Belinda and Priscilla Sutton.Footnote 60 The atmospherics as well as the institutional situation had changed dramatically. Royall’s new executors felt safe in offering an exonerating description of his 1775 flight from Boston. They depicted him not as a refugee or absentee, but as a loyal albeit hapless invalid, and made note that the estate had been returned to his executors. Isaac Royall had, it seems, gotten a posthumous moral get-out-of-jail-free card:

Humbly sheweth that the said Isaac Royall being in an infirm state of health was induced to leave this commonwealth in the year 1775 by the Earnest entreaties & solicitations of his friends & that he was for some time considered as an absentee & his Estate taken possession of by the Government, but upon consideration of the circumstances under which he went away the whole was afterwards restored, a sum of money however remained in the treasury of the commonwealth – intended to provide for the support of two family servants who were left behind & to prevent their becoming public incumbrances [sic]. As the last of said family servants is now dead your Petitioners pray that the Treasurer of the Commonwealth may be authorized and directed to settle & pay over the balance of said deposit remaining in his hands to your said petitioners for the benefit of the heirs of said Isaac Royall.Footnote 61

Belinda and Priscilla must be the two servants for whom these funds were reserved: there simply are no other candidates. That neither woman petitioned again after 1793 suggests that sufficient support payments had been made from the escrow set aside in the Commonwealth Treasury – or that both of them had died so soon after funds became available that no legal process could be brought on their behalf. I have not found any record of their deaths.

Isaac Royall, Jr.’s bequests to Harvard and other elite public interests in the new Commonwealth cemented his posthumous rehabilitation. In 1797, Hall petitioned the General Court seeking to recoup for Royall’s heirs funds which, he claimed, had been wrongfully appropriated from the estate. He supported his claim by emphasizing Royall’s “very large and liberal Donations … to the University at Cambridge, and to other Public and benevolent uses, in this Commonwealth.”Footnote 62 James Henry Stark, in his biography of Isaac Royall, Jr., in The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution, acknowledges that Isaac Royall, Jr.’s bequests to Harvard College and other public causes constituted an intentional and successful rehabilitation campaign.Footnote 63 The unpaid bequests also created important incentives for an array of Massachusetts elites to side with Hall and the Royall heirs. When those bequests were paid out, they reintegrated him, symbolically, into the elite symbolic landscape of Boston and Cambridge.

The capstone of Isaac Royall’s re-rise came in 1815 when Harvard accepted its bequest and established the Royall Chair. This decision had to be both the effect and the cause of a complete reversal of reputational fortunes. And it paid itself forward. Isaac Parker, the first occupant of the Royall Chair, gave an inaugural lecture in which he invited “future benefactors” to follow in Royall’s footsteps, and to fund not just a Chair but a school of law. They too could bask in the glow of the commitment to freedom and equality that motivated, Parker imagined, Royall’s original bequest:

[Law] should be a branch of liberal education in every country, but especially in those where freedom prevails and where every citizen has an equal interest in its preservation and improvement. Justice therefore ought to be done to the memory of Royall, whose prospective wisdom and judicious liberality provided the means of introducing into the university the study of law.Footnote 64

The university as reputation-launderer – (re)cycling virtue from its production of socially beneficial knowledge to its donor base and back again – here rears its immemorial head. There is nothing “neo” about it.

Isaac Royall, Jr. was back in the 1 percent. Not only that: surprise! He was a fount of the liberality that defined the new republic. Meanwhile, the voice denouncing Royall as a slaveholder, slave trader, and exploiter of slave labor had been silenced over the long course of Belinda’s miserable treatment – and perhaps by it. It now goes quiet for almost 200 years.

The Royall/HLS Shield

The next major merger of the Royall brand with that of HLS came in 1936, when Harvard University adopted the Royall coat of arms as the Law School’s mark (Figure 9.4). We are going to follow its rise and successive transformations up to 2016 when, in response to a Law School report concluding that the mark was so stigmatic that University leadership should “release us from” it, the Royall/HLS shield was disappeared.Footnote 65

Figure 9.4 Royall/HLS shield. HLS retired and removed this shield in March, 2016 (see Figure 9.13).

By 1936, a small near-hagiography of Isaac Royall, Jr. had come into print, provided by boosters of Medford and Harvard. An 1855 history of Medford by Charles Brooks picked up where the 1799 petition left off, regretting that Royall, a “timid” man,Footnote 66 was “frightened into Toryism”Footnote 67 by the outbreak of hostilities on April 19, 1775. “He was a Tory against his will,”Footnote 68 but only because “He wanted that unbending, hickory toughness which the times required.”Footnote 69 But much could be said on Royall’s behalf, including his bequest founding the Royall Chair.Footnote 70 “Happy would it be for the world, if at death every man could strike as well as he did the balance of this world’s accounts.”Footnote 71

Brooks acknowledged that Royall had been a slave owner, but it did not appear to weigh heavily against him: after all, “As a master he was kind to his slaves, charitable to the poor, and friendly to everybody.”Footnote 72 This assessment comes just pages after Brooks reports Royall’s instructions to Simon Tufts, by then his agent, on March 12, 1776, almost a year into his exile:

Please to sell the following negroes: Stephen and George: they each cost ₤60 sterling; and I would take ₤50, or even ₤15 apiece for them. Hagar cost ₤35 sterling, but will take ₤25. I gave for Mira ₤35, but will take ₤25. If Mr. Benjamin Hall will give the $100 for her which he offered, he may have her, it being a good place. As to Betsey, and her daughter Nancy, the former may tarry, or take her freedom; and Nancy you may put out to some good family by the year.Footnote 73

Perhaps it was kind to prefer a good place for Mira and a good family for Nancy. But the fire sale prices contemplated for Stephen and George suggest that they were old or disabled; they were being offloaded in all their vulnerability. Chan argues that the Royalls seldom separated mothers and daughters,Footnote 74 and we know that emancipating a slave without providing security for her support was against the law. Yet in his driving need for money, Isaac Royall, Jr. was blowing through multiple norms held even in a slave society. The sheer audacity of selling human beings because you can do it makes this letter, to us, a scandal; Brooks had no problem with it, or any of the lesser cruelties embedded in this episode.

When Charles Warren published a history of HLS in 1908, he lifted entire passages from Brooks’ account, including the “kind to his slaves” nostrum,Footnote 75 but he balked at including Royall’s letter to Tufts. In Warren’s eyes, Harvard’s reputational requirements – or maybe just space limitations – subjected Royall’s character as a slave owner to a deliberate forgetting.

All of that preceded the 1936 adoption of the Royall/HLS shield by a generation. We are about to trace the Royalls’ ersatz heraldry as it morphed into a modern logo with various forms of ever-deepening oblivion covering Isaac Royall, Jr.’s political and moral deficits.

The backdrop of this struggle is, again, British practice. When a royal or aristocratic family chartered and endowed a college at Oxford or Cambridge, the Crown would authorize a shield, adapted (“differenced” in heraldry-speak) from the granting family’s shield, for its exclusive use. The result was another official, state-sponsored system of marks representing the carrier’s royal charter or memorializing the aristocratic or institutional status of its founding donors.Footnote 76

Seven years after the founding of Harvard College, way back in 1641, its Overseers imitated this homeland practice by adopting a mark for the College. They authorized a “seal,” shaped like a shield and bearing the word VERITAS across the figures of three books (Figure 9.5).Footnote 77 The mark was not granted by Crown authorities in London or in the colony. Once again, assumed arms.

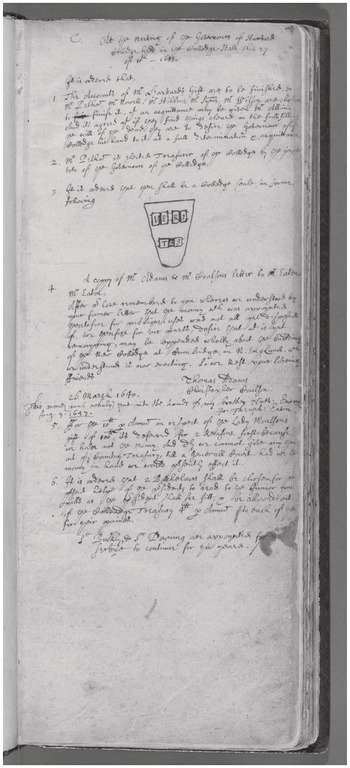

Figure 9.5 Original sketch of the Harvard seal. Harvard University. Corporation. College Book 1, 1639–1795. UAI 5.5 Box 1.

Though the motto and design have changed from time to time,Footnote 78 this shield-shaped seal had remained in intermittent use for almost 300 years when, in 1935/36, the University tercentenary loomed. Outgoing President Abbott Lawrence Lowell had bestowed arms on the first seven residential houses and he was gunning to carry on.Footnote 79 He strove for authenticity when he could get it, but when the British College of Heralds charged a heavy fee to authenticate a pirated coat for Dunster House, “President Lowell resolved that thereafter the University would proceed heraldically on its own.”Footnote 80 The new president, James B. Conant, who disliked Lowell’s pomp and circumstance, ceded to him the role of “President of the Day” of the tercentenary celebrations. Doubtless following Lowell’s cue, the director of the tercentenary celebrations decided that sub-units of the University should display heraldic shields in the upcoming celebrations. He commissioned Pierre de Chaignon La Rose, a member of the University’s Committee on Arms, Seal, and Diplomas and its expert on heraldry, to design banners for the College, the graduate schools, and seven residential houses to fly at the tercentenary celebrations.Footnote 81 In a later defense of his insignia, La Rose invoked the British practice of bestowing coat armor on Oxbridge colleges.Footnote 82

Not only did his suite of arms lack official authorization, they trenched on the exclusivity of the University’s almost 300-year-old seal. Resistance came from Samuel Eliot Morison, the Chair of the University’s Committee on Arms, Seal, and Diplomas, who had written in 1933 that the Harvard shield could be used by sub-units of Harvard with limited variation of the design, but that the seal was a legal mark for the exclusive use by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.Footnote 83 He was probably the moving force when, a year before the tercentenary celebrations, the Office of the Governing Boards issued a four-page pamphlet, The Arms of Harvard University: A Guide to Their Proper Use, asserting its exclusive right to the use of the seal:

Any member of the University or any group of graduates is at liberty, as are the University and its various departments, to make decorative use of the Harvard Arms. But no one, except the Governing Boards of the University, may use the official Seal; for a seal is not a decoration but a legal symbol of authentication.Footnote 84

The pamphlet instructed sub-units of Harvard that they could “combine the Arms with their own title” and advised them to seek advice from the Secretary to the Corporation (the term for the governing body made up of the President and Fellows) about how to draw up a design to surround it, such as an ivy garland or cartouche; however, it ruled out a circular inscription, which would make the overall design too similar to the seal. Commercial firms were instructed that they could use the arms as “a pleasant decoration on stationery (printed in black or red), on jewelry, book-ends, etc.,” but not on “clothing, arm-bands, ‘stickers,’ and the like.” “The Arms should always be treated with dignity[.]” For guidance, manufacturers using the arms were directed to the University Purchasing Agent. The pamphlet left it to be understood that the Office of Governing Boards would police uses inside the University and possibly even sue outsiders who exceeded the narrow permissions granted.Footnote 85 In a tentative and uncertain way, the Corporation was invoking common-law and equitable rights to exclusive use of its trademark.Footnote 86

La Rose’s design for the College’s shield adopted a design apparently ruled out in the pamphlet: it was “the present coat of the University, differenced, however, by the reintroduction of the chevron which for many years appeared on the Harvard seal.”Footnote 87 He went even further into conflict with the pamphlet’s proper-use guidelines in his design for the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, adding a “‘fess’ (horizontal stripe) between the books instead of a chevron.” La Rose defended these unauthorized innovations as “strictly in accord with heraldic precedents.”Footnote 88

For the Law School, La Rose’s choice was obvious: the Oxbridge analogy led directly to the Royall shield. Isaac Royall, Jr., if he could have lived to see this, would have been delighted. He was being analogized to an aristocratic British family – even a royal one – founding an Oxbridge College; and the Law School tout court, not merely its first professorship, was being credited to his gift. There was not the slightest acknowledgement of Belinda or the other human beings held in bondage.

But once again the mark was controversial – this time, simply in its status as a mark. La Rose brought on the controversy by seeking official University adoption of his arms. In June 1937, he petitioned the University’s Committee on Arms, Seal, and Diplomas to approve his designs: to make them official at least as far as the University went, and thus to elevate them closer to the status that their analogues occupied in the Oxbridge symbolic branding landscape.Footnote 89 Within days, the Committee forwarded La Rose’s petition to the Corporation, thereby placing the proposal in President Conant’s court.

The Corporation did not act on the proposal until early December,Footnote 90 and during this interval the Committee received a letter from the New England Historic Genealogical Society Committee on Heraldry attacking the La Rose designs in the name of heraldic purity. “[M]ost of the school arms” designed by La Rose were based on “false assumptions.” We know by now that “assumptions” is used here as a term of heraldic art, not as a reference to an unproven premise in a logical argument. “[I]t would be a mistake” for the University to “put itself in the position of sanctioning” them. The Royall arms came in for particular criticism:

…this Committee has no evidence that the New England family of Royall had a right to the coat. It should be remembered that the unauthorized assumption of arms became extremely fashionable in our colony at about the time that the local Royalls seem to have begun using the arms of the English family of that name. The parentage of William Royall of Dorchester, the progenitor of the family, who died in 1724, is unknown to this Committee.Footnote 91

The Royall name was dashed again, this time for pirating the authentic arms of an English family of the same name.

In the end, the Corporation gave a very limited sanction for the use of the designs: “the Corporation, while having no objection to the use for decorative purposes on the occasions of ceremony or festivity of the blazons proposed for the several departments or faculties, do not approve their use for other purposes.”Footnote 92 The idea that the graduate faculties and residential houses should have official marks of their own would have given them equal status, as far as heraldry goes, with the University itself. But the University and its seal had already occupied this field, and the Corporation had no wish to share it. To this day, degrees are not granted until approved by the Corporation, and diplomas throughout the University bear the University seal; the La Rose shields are not allowed to authenticate – or even to adorn – these critical documents.Footnote 93

By the time the Royall shield next became the object of campus controversy, its origins in heraldry and the controversies belonging to its heraldic dignity (or lack thereof) had been forgotten; over the latter half of the twentieth century, the semiotic register in which it signified shifted from the language of heraldry to that of commercial trademarks.

From New Corne to Corporate Trademark

My colleague Charles Donahue fills in the next stage in the re-re-re-signification of the Royall brand: this time, he argues, as an effort to erase Isaac Royall and rewrite the shield quite completely. Donahue reports that early in his deanship, HLS Dean Erwin Griswold (served 1946 to 1967) had the shield inscribed on the pediment of a beautiful bookcase that had been permanently installed in the Treasure Room (now the Caspersen Room)Footnote 94 (Figure 9.6). The inscription originates in Chaucer’s poem The Parliament of Fowls:

As Donahue reports, this was a favorite source for the English jurist Sir Edward Coke, to whom it signified the ever-renewing traditionalism of English common law: “To the Reader mine Advice is, that in Reading of these or any new Reports, he neglect not in any Case the Reading of the old Books of Years reported in former Ages, for assuredly out of the old Fields must spring and grow the new Corn[.]”Footnote 96 And for that reason, in turn, it was a favorite motto for Griswold, who borrowed from it for the title of his memoir, Ould Fields, New Corne: The Personal Memoirs of a Twentieth Century Lawyer.Footnote 97 There is no sign in Griswold’s papers, housed in Langdell Library, that he knew or cared that Isaac Royall, Jr. had been a major slaveholder and trader;Footnote 98 rather, Donahue suggests that Griswold probably thought it would be good to have less of Isaac Royall because of his doubtful loyalty to the American cause. And so he rewrote the shield in the key of Coke, as a symbol of the ever-stable, ever-renewing fount of human wisdom that is the common law.

Figure 9.6 Bookcase in the Caspersen Room with the Royall/HLS shield.

This was a normatively rich, highly self-congratulatory gloss on the shield. Senior colleagues have told me that, to them, this was what the shield meant. It anchored, in their minds, high ideals for the proximate relationship between law and justice. For them, the association with the Royall family, much less with its slaveholding and slave-trading practices, was not even forgotten: it was simply and completely unknown.

Fast-forward to the postwar Law School, when the shield began to appear on a few “old school ties” (Figures 9.7 and 9.8). In an eerie echo of the bottles then still buried in the slave quarters’ yard at Isaac Royall’s house in Medford, HLS Professor Archibald Cox had it embossed on a wine bottle (Figures 9.9 and 9.10). The 2016 HLS report recommending the shield’s removal observes that its use expanded dramatically in the mid-1990s.Footnote 99 This is when it appeared carved in wood as a presiding emblem high behind the bench in Ames Courtroom, and replaced the University seal behind the introductory matter to Ames Competition videos.Footnote 100 It began to appear everywhere: on letterhead, mats laid down to protect people from slipping when entering buildings on rainy days, webpages, syllabi, infinite varieties of Law School swag offered for purchase at the Coop or given away at conferences, retreats, fundraisers, alumni gatherings, graduation celebrations, et cetera.

Figure 9.7 Advertisement.

Figure 9.8 Wm. Chelsea LTD, Scarsdale, NY, “Harvard Law School Silk Necktie.”

Figure 9.9 Glass bottle with Royall family shield. Theresa Kelliher for the Royall House and Slave Quarters.

Figure 9.10 Heitz Wine Cellars, St. Helena, CA, “Wine bottle belonging to Archibald Cox.”

In cultural use, it was becoming a logo, the equivalent of the Nike swoosh or the (football) Patriots’ helmeted avenger. All of this was in flagrant violation of the restrictions set by the Corporation in 1936, of course, but who cared? It was also quite out of tune with Griswold’s lofty ambitions for the resignified shield, but who needed anything so heavy? Let a thousand shields bloom!

The dean under whom this efflorescence took place, Robert C. Clark (served 1989 to 2003), still speaks of developing the School’s “brand,” especially to distinguish it from Yale Law School. HLS was vastly larger, more international, more global, more connected to its sister professional schools:Footnote 101 a city to Yale’s club. The “university as brand” – complete with a charismatic mark – had arrived at HLS. Clark, who remembered enjoying the mentorship of Griswold during his deanship, has repeatedly told me that he saw the shield through the “ould fields, new corne” lens, which had effectively erased its Royall origins. Nor did he associate the Royall Chair, which he selected for himself when he became dean, with the shield, or with slavery. During this period, I can find no inkling in the Law School’s branding landscape of a taint on the shield or its family of origin. As late as 2005, the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice celebrated its grand opening brandishing the three-garbs shield (Figure 9.11). For the time being, the shield was everywhere and presumed to be benign; the Chair was the dean’s because the dean had it; and the original donor who linked them was forgotten.

Figure 9.11 Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice Grand Opening Celebration web page.

Meanwhile, three miles away from the Law School, the institution founded to preserve Isaac Royall’s actual home was shaking itself to its foundations to take seriously Royall’s legacy as a slave owner and slave trader.

From the Elegant Royalls to the Royall House and Slave Quarters

In 1906, the Royall house in Medford faced demolition to make way for suburban homes. The Daughters of the American Revolution – made up exclusively of proven female descendants of patriot fighters in the Revolutionary War – bought the property and entrusted its care to a newly established nonprofit, the Royall House Association.Footnote 102 To them, the value of the house would have been its association with George Washington, who is said to have interrogated two British soldiers there, and with General John Stark, who encamped there.Footnote 103 They curated the site in the spirit of colonial-revival nostalgia. As Chan reveals, the Royall House Association sponsored re-enactments of high tea out on the lawn, complete with white gentlemen and ladies in elaborate colonial garb and servants in blackface (Figure 9.12).Footnote 104

Figure 9.12 Tea ceremony at the Royall House.

Almost simultaneously, a similarly Tory interpretation of Isaac Royall, Jr. was underway in the form of a hagiography of the loyalists (such are the reversals wrought by time). In 1907, James Henry Stark published his massive The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution, a thoroughgoing, family-by-family account of the victimization of the loyalists by the revolutionary elites, both during and after the Revolutionary War. He included detailed and highly favorable accounts of Isaac Royall, Jr. and his sons-in-law Sir William Pepperell and George Erving as well as his brother-in-law Henry Vassall.Footnote 105 Isaac Royall’s colonial politics and flight to London were reinterpreted yet again: he and his family finally found voice as the darlings of pro-loyalist reactionaries.

Much-softened revisions of these apologies reappeared sixty years later, once again reworking Isaac Royall’s reputation to serve the reputational needs of contemporary institutions, this time HLS and the Royall House Association. In a 1967 history of HLS, Arthur E. Sutherland styled the Revolutionary War a “civil war”; construed Royall’s Anglican and Anglophile alliances to his credit; and reflected that the Feke portrait, then hanging in the entrance hall to Langdell Library, and the Royall Chair offered fitting reminders that, even at stressful moments in history like Sutherland’s present – 1967 was plenty tumultuous politically in the US – “generous impulses could survive even ingratitude, disappointment, and disillusion.”Footnote 106 Like many historical accounts produced in mid-century America, Sutherland reconfigured Royall’s enslaved human beings as “Negro ‘servants’” and is otherwise silent on the subject.Footnote 107

And just a few years later, in 1974, Gladys N. Hoover, a member of the Royall House Association,Footnote 108 published The Elegant Royalls of Colonial New England as her contribution to the upcoming national bicentennial. Explicitly following Brooks, she defended Royall as a timid mediator.Footnote 109 Juxtaposing him with Paul Revere the patriot and Sir William Pepperell the true loyalist, she urged: “Honor to the consciences of all three!”Footnote 110 But she did not think that the family’s slavery legacy needed excuse. Of their years in Antigua, she noted the island’s “equable and delightful climate” and optimal conditions for agriculture: “Conditions for growing sugar cane were perfect there and black slave labor was abundantly available.”Footnote 111

The turning point came in 1988, when Peter Gittleman, a freshly minted Master of Arts in Preservation Studies from Boston University, toured the house. The site included the Georgian mansion house built by Isaac Royall, Sr. and, only thirty-five feet away, the highly conspicuous slave quarters. The tour guide dwelt on Isaac Royall’s wealth and de luxe way of life, making no mention of the enslaved people so manifestly connected to the site. As Gittleman later related, “my jaw dropped.” He joined the Board and formed an alliance with Julia Royall, an eighth-generation collateral descendent of Isaac Royall already on the Board, and together they mounted a long, careful campaign to convert the Royall House to the Royall House and Slave Quarters.Footnote 112

It was slow work. Clearly there was significant opposition within the Board. In 1999, it commissioned Chan to do her archaeological explorations, specifically to enrich knowledge about the lives of those enslaved at the site. She conducted digs over three seasons and published the results as her dissertation in 2003.Footnote 113 The Board held a Planning Retreat in June 2005 and began to revise the mission statement and to redirect the Association.Footnote 114 The following December, the Board announced “A New Vision for a New Age”:

…we have adopted a new mission statement:

The Royall House Association explores the meanings of freedom and independence before, during and since the American Revolution, in the context of a household of wealthy Loyalists and enslaved Africans.

In charting this course, we recognize that many people will have strong emotional and philosophical reactions. Some may feel we are devaluing what has been the primary narrative thread, playing to political correctness. Others may feel that an organization that has been run and supported primarily by white people has no legitimacy to tell the story of enslaved blacks. Still others may feel it is a story that is too painful or embarrassing, that it would not appeal to visitors simply looking for a pleasant journey into the past. We do not underestimate the task before us. It will be difficult and, at times, unpleasant. It will require a different sort of organization than we have been. We would be sorry to lose some friends and supporters but trust that people who share our passion for the educational potential of this place will replace them. But these are all reasons to work harder, not to avoid the challenge.Footnote 115

A majority of the Board was moving forward even if it meant that some members and donors, strongly opposed to the new direction, resigned or closed their checkbooks. The reformers changed the site’s name and embarked on its top-to-bottom reinterpretation.

Meanwhile, on an entirely separate path, HLS was also moving toward a reckoning. In September 2000, Professor David B. Wilkins inaugurated a semi-annual Celebration of Black Alumni, welcoming hundreds of graduates back to campus for programs held under a huge white tent in Holmes Field. The lunchtime speaker – Coquillette, who was at the time preparing his history of the Law School, together with Kimball – was asked to share his research on the history of black students at HLS. The audience expected a retelling of a familiar story, from George Lewis Ruffin to Charles Hamilton Houston to Reginald Lewis, and that’s what they got, but with a surprise. Coquillette distributed a “Black History Quiz” made up to look like a Law School examination, with images of important figures in the Law School’s history. The first question – essentially, “Who is this person?” – was about a collection of three images: Isaac Royall, Jr. (taken from the Feke portrait), the Slave Quarters in Medford, and a group of enslaved black workers toiling in a sugarcane field. Spectacularly, no one could identify these images or how they were associated. Coquillette then dropped an Isaac-Royall bombshell: these were Isaac Royall, Jr., the donor of the first Chair in law at Harvard; his slave quarters in Medford; and enslaved laborers in Antiguan sugarcane fields.Footnote 116 Coquillette proceeded to publish a short “banner” article in the Law School’s alumni magazine titled “A History of Blacks at Harvard Law School.” In sixty-seven words, he published, for the first time, the bare-bones story of Isaac Royall, Jr., his Chair bequest, and his slaveholding.Footnote 117

Chan’s and Coquillette’s researches were simultaneous but independent.Footnote 118 Gathering the fruits of their work, I gave my 2006 lecture to the gathered law faculty: the title was “Our Isaac Royall Legacy.”Footnote 119 Then, in 2015, Coquillette and Kimball published On the Battlefield of Merit, complete with their full account of the legacy of the Chair – and, subsequently, Harvard Law School itself – in enslaved labor.Footnote 120

In Medford and at HLS, the stigma of slavery that Belinda had affixed to Isaac Royall’s name was back.

Engagement v. Repudiation

Knowledge that Isaac Royall, Jr. was tied to HLS through the Royall Chair and that he was a slaveholder and slave trader, called many to offer some kind of moral and/or political response. Two approaches emerged: clean hands, which required repudiation or distancing of some kind, and engagement, which could never be conclusive or fully perfect. The Royall House and Slave Quarters had chosen engagement. What would HLS do?

In 2003, when Elena Kagan stepped into the HLS deanship, she did not select the Royall Chair, which was available to her because Dean Clark had vacated it and the office simultaneously. Instead, she took the newly endowed Charles Hamilton Houston Chair. That Chair, funded by an anonymous gift, was named for a black HLS graduate who had played a leading role in fostering a cadre of black civil rights lawyers,Footnote 121 who is sometimes dubbed “the man who killed Jim Crow,”Footnote 122 and who mentored Thurgood Marshall, the Justice for whom Kagan had clerked.Footnote 123 This made a lot of sense: Coquillette had affixed the slavery stigma to the Royall Chair in his Celebrating Black Alumni lecture three years before, a fact of which Kagan had to be fully aware. Why go there? And the Houston Chair was brand-fresh; it’s very possible that Kagan had even been involved in its creation. Quoted in Harvard Law Today, the School’s in-house outlet for carefully groomed news about itself, she proudly pointed to the lineage from Houston to Justice Marshall to herself.Footnote 124 It was a deft, elite, civil-rights- and self-affirming branding strategy.

Seven years later, however, when rumors flew that President Obama was going to nominate Kagan for a post on the US Supreme Court, a group of left-of-center law faculty of color attacked her decanal faculty-hiring record for being a diversity desert.Footnote 125 They basically accused her of talking the talk but not walking the walk. In response, nominee Kagan’s supporters offered a Royall-themed talking point: the Royall Chair was by “tradition” the Dean’s Chair, and yet Kagan had “declined” it when she became dean in 2003 precisely because of its slavery taint, taking instead the Charles Hamilton Houston Chair, symbolically the Royall Chair’s new virtual opposite.

The tradition/taint/decline/instead narrative became a small but persistent element of Kagan’s vicarious campaign for confirmation as Supreme Court Justice, debuting on May 12, 2010. HLS Professor Randall Kennedy offered support for Kagan’s nomination with praise for her pride in being the first Charles Hamilton Houston Chair, but made no reference to her declining the Royall Chair.Footnote 126 His version was fully supported by Kagan’s own public statement quoted in Harvard Law Today.Footnote 127 The full story complete with the taint of the Royall Chair, the tradition that it was the Dean’s Chair, and Kagan’s refusal to take it, first emerged in a post by HLS Professor Charles J. Ogletree, Jr., which claimed that all the Law School deans had held the tainted Chair.Footnote 128 HLS clinical faculty member Ronald Sullivan made the more modest claim that the Chair was merely traditionally the dean’s.Footnote 129 And from there the narrative jumped to position papers supporting Kagan’s nomination that national political groups submitted to the Judiciary Committee.Footnote 130 Sullivan repeated it at Kagan’s confirmation hearing.Footnote 131 And thence it entered the bloodstream of journalistic copy-and-paste, in articles written without any effort to fact-check the dubious elements of the story.Footnote 132

After much searching, I have found no instance of Kagan relating the tradition/taint/decline/instead narrative; nor have I been able to find any press or other coverage of it before 2010. In addition, I have two further bits of evidence that Kagan was probably not deeply invested in repudiating Isaac Royall, Jr., and his Chair. Leaving the Chair empty was an option, but in 2003 she gave it to David Herwitz, a very distinguished, very senior tax and accounting specialist. I doubt that a supreme strategist – which Dean Kagan assuredly was – would have placed what she understood to be an institutional reputational liability on the shoulders of a faculty member with zero track record in social-justice mud wrestling. And then, when Herwitz retired, she gave it to me, when I was in the most bad-girl phase of my career. Armed with the Royall Chair, I could have done the institution a lot of damage. She seems not to have fully grokked the potential for virtue-signaling repudiation that Coquillette’s revelations enabled.

And I think that’s to her credit. This story can help us see one of the dangers of the repudiation route: the way in which it tempts those on it to craft Manichean good-and-evil patterns out of more complex and ambiguous human material.

It starts back in 2000, right in Coquillette’s quiz lecture. His Royall narrative contains two exaggerations, both of which can be reduced to more accurate size using his, and Kimball’s, own work on the Royall Chair! In 2000, it was not enough for Coquillette that the Royall Chair was the first Chair in law at Harvard; instead, Royall’s “bequest established the Harvard Law School.” And it was not enough that the Royall Chair “was the most senior endowed chair in the Law School”; rather, it was also “traditionally occupied by the Dean.”Footnote 133 The latter exaggeration is probably the origin of the link to tradition found in the pro-Kagan campaigners’ tradition/taint/decline/instead narrative. Turns out, sadly for the narrative, that it isn’t true. Nor did the Royall bequest establish the Law School. Here is what happened instead.

As we have seen, the Royall Chair, first established in 1815, and first occupied by Isaac Parker in 1816, was initially a part of Harvard College. The Law School did not open until 1817.Footnote 134 In expanding from a single professorship to a School, the University launched on an experiment in legal education as a university-based professional education for postgraduates. As Coquillette and Kimball reveal, the School’s original business model – an inadequately funded Royall Chair held by Parker and dedicated to undergraduate lectures, when he could be spared from his duties as Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, plus a tuition-funded professor, Ashael Stearns, with responsibility for everything necessary for the construction of a Law School – was profoundly unstable.Footnote 135 The Royall Chair did not establish the School, though Parker, its first holder, tirelessly campaigned for it.Footnote 136

And second, it was the Dane Chair, not the Royall Chair, that traditionally, in the School’s first seventy-five-odd years, belonged to the dean. The Law School enterprise did not become viable until Joseph Story took a second endowed chair, the Dane Professorship, on carefully negotiated terms that made him the leader of the new School.Footnote 137 When Story died in 1845, Simon Greenleaf relinquished the Royall Chair to assume both leadership and the Dane Professorship.Footnote 138 The place was known as the “Dane Law College,”Footnote 139 and rightly so: Nathan Dane’s endowment gift enabled the establishment of a full-fledged, sustainable School. He later made the loan that structured co-financing by himself and the College to create Dane Hall, the School’s first freestanding building.Footnote 140 He contributed a major impetus to Story’s career as treatise-writer par excellence.Footnote 141 And he was an anti-Royall in the sense that he consistently played a role in anti-slavery politics. He had drafted the Northwest Ordinance in 1787, which abolished slavery in the new territory; and participated in the secessionist Hartford Conference in 1814.Footnote 142 If a new twenty-first-century dean wanted to signal commitment to civil rights by taking a Chair traditionally associated with the leadership of the School – the Dane Chair, specifically – he or she might have to revive this forgotten, anti-slavery piece of HLS history.

In 1846, the Corporation issued new rules interrupting the Dane leadership tradition. They required that the senior professor would be considered the “head” of the School; that the Dane and Royall professors had joint responsibility for the course of instruction; and that the faculty “equally and jointly ha[d] the charge and oversight of the students.”Footnote 143 In this arrangement, there was a “head” of the School but no dean, and both the Royall and Dane Chairs were subordinates with defined responsibilities.

In 1870, President Eliot erased this teamwork division of labor when he inaugurated the office of dean and persuaded Christopher Columbus Langdell to fill itFootnote 144 – as the Dane Chair.Footnote 145 The President wanted, and got, a strong dean with the power to make big changes and answerability to him rather than to a disorganized passel of colleague-subordinates.Footnote 146 The Dane Chair was back on top, and for the first time it was the Chair of a dean.

But Langdell proceeded to break the revived link between the Dane Chair and the leadership role by holding onto the former when he resigned from the latter in 1895.Footnote 147 Between Langdell and Robert C. Clark there were nineteen deanships, but only two were Royall Professors. Joseph Henry Beale took the Royall Chair in 1913,Footnote 148 and served as dean in 1929/30; Edmund Morris Morgan occupied the Royall Chair from 1938 to 1950,Footnote 149 and served as acting dean in 1936/37 and from 1942 to 1945.Footnote 150 In neither case was there any relationship between their holding the Chair and serving as dean. Clark provided the first reason to think of the Royall Chair as the dean’s Chair when he assumed it upon becoming Dean in 1989 and relinquished it when he returned to the faculty in 2003. There is a rumor, which I have heard several times but cannot substantiate, that Clark took the Royall Chair from its prior occupant because he thought that, as dean, he was privileged to hold it. The rumor, to be sure, supports the traditionally-the-dean’s-chair line but only as an urban legend: it can’t be true. Vern Countryman, the Royall Chair right before Clark, retired in 1987,Footnote 151 leaving the Chair vacant until Clark selected it two years later. Clark informed me – and I believe him – that when he left the deanship, he gave up the Royall Chair not to make way for the new dean but because he had cultivated the gift of the Austin Wakeman Scott Chair in part by promising the donor that he would be its first occupant.Footnote 152

Thus the Royall Chair was not traditionally the dean’s chair. Originally, the Dane Chair belonged to the head of the School; in the late nineteenth and through the twentieth centuries, no chair was associated with the deanship. Clark’s one-off stint as both Royall Chair and dean provided the hook for an invented tradition that, like most invented traditions, is a pastiche of truth and fiction.

I think there is a lesson here about the dangers of moral repudiation as a branding exercise. On the repudiation path, Royall, the Royall Chair, and their relationship to the School had to be aggrandized in order to more effectively convey a shocking taint and to deflect all the light in the room onto the virtue of the repudiator. This happened when Coquillette first introduced the HLS community to Isaac Royall, Jr., at the Celebrating Black Alumni event, and again when nominee Kagan’s supporters embellished her careful decisions and messages about her Chair in an effort to make of them a good-against-evil story. Yet the Isaac Royall precedent is bad enough without exaggeration.

Much later, when the press began to add that Dean Martha Minow (served 2009−17) had also declined the Royall Chair, “traditionally reserved for the dean,”Footnote 153 the story made even less sense. She would have had to take it away from me to bestow it on herself (which she never suggested doing) and, by then, why would she? The taint was public knowledge and I was doing my sorry best to keep it alive by distributing the published version of my Chair lecture and taking tours for various HLS constituencies to the Royall House and Slave Quarters. Moreover, Minow’s path was engagement, not repudiation. She hosted welcome-to-HLS dinners for 1L sections in the Caspersen Room so that she could point to the Feke portrait and invoke the Isaac Royall slavery legacy as an object lesson in the chasm that can separate law and justice.Footnote 154 She was acknowledging the hard work of moral sorting. The opposite of repudiation.

The momentum to repudiation would not begin its rush until 2015.

“Royall Must Fall” and the Demands

During the academic year 2015/16, HLS was the scene of multiple student movements focused especially on racial injustice in the world and at the School. Students mounted sustained and multi-front protests against their legal education and called for change. They re-re-re-re-signified the Isaac Royall/HLS shield to focus directly and exclusively on the fact that it memorialized the donor of the first Chair in law at Harvard who was a slaveholder. Isaac Royall, Jr.’s brand took a nosedive; the dean convened a special committee to make a recommendation about the shield; the committee recommended elimination of the Royall/HLS shield; and the Corporation acceded to that advice. The shield came down all over the School and throughout its many productions (Figure 9.13).

Figure 9.13 Removing the shield from Ames Courtroom.

I was involved in the protests, in consulting with some of the protesters, in faculty discussion of the School’s response to the protesters, and on the special committee empaneled to consider what to do about the shield. I was also personally denounced as a racist by one of the protesters, in part for benefiting from the Royall Chair. Every step of the way was intensely controversial. It will be even more than usually impossible for me to be objective about what it all meant. But I’ll try to write it so that those who disagree with my interpretation of it, and those who chose for themselves very different roles in it, can see it in retrospect as a story not only about social good and evil, or political wisdom and folly, but also about a brand and its mark.