Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Maps

- Introduction

- 1 A bed of his own blood: Nombuyiselo Ntlane

- 2 This country is my home: Azam Khan

- 3 On patrol in the dark city: Ntombi Theys

- 4 Johannesburg hustle: Lucas Machel

- 5 Don't. Expose. Yourself: Papi Thetele

- 6 The big man of Hosaena: Estifanos Worku Abeto

- 7 Do we owe them just because they helped us?

- 8 Love in the time of xenophobia: Chichi Ngozi

- 9 This land is our land: Lufuno Gogoro

- 10 Alien: Esther Khumalo*

- 11 One day is one day: Alphonse Nahimana*

- 12 I won't abandon Jeppe: Charalabos (Harry) Koulaxizis

- 13 The induna: Manyathela Mvelase

- Timeline

- Glossary

- Selected place names

- Contributors

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 May 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Maps

- Introduction

- 1 A bed of his own blood: Nombuyiselo Ntlane

- 2 This country is my home: Azam Khan

- 3 On patrol in the dark city: Ntombi Theys

- 4 Johannesburg hustle: Lucas Machel

- 5 Don't. Expose. Yourself: Papi Thetele

- 6 The big man of Hosaena: Estifanos Worku Abeto

- 7 Do we owe them just because they helped us?

- 8 Love in the time of xenophobia: Chichi Ngozi

- 9 This land is our land: Lufuno Gogoro

- 10 Alien: Esther Khumalo*

- 11 One day is one day: Alphonse Nahimana*

- 12 I won't abandon Jeppe: Charalabos (Harry) Koulaxizis

- 13 The induna: Manyathela Mvelase

- Timeline

- Glossary

- Selected place names

- Contributors

Summary

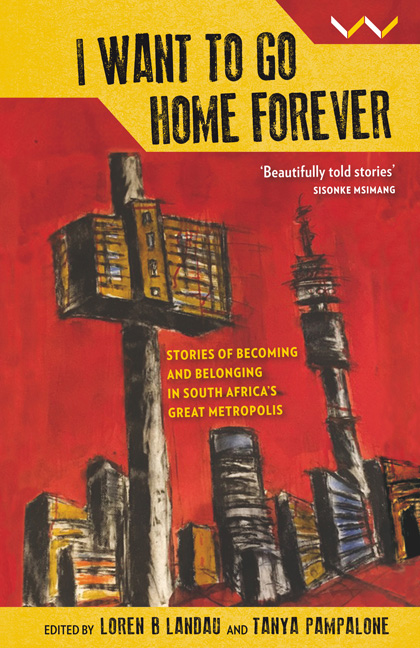

It has been a bit more than two decades since apartheid gave way to democracy and the buildings that house the Constitutional Court look worn. The expressions boldly inscribed on the walls in South Africa's 11 official languages – words pledging, among other constitutional commitments, that the country ‘belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity’ – are fading under the fierce Highveld sun. Some letters are missing, likely pried from their surface to sell as scrap metal alongside many of the city's manhole covers.

In its former life, the court was an imposing military fort and prison where apartheid's antagonists were detained and tortured. Now, from its hilltop perch in the heart of Johannesburg, Constitution Hill overlooks a place of promise: the noisy, dynamic, sometimes dangerous downtown centre of Hillbrow, an unwitting symbol of South Africa's transformation. Once a gateway for European immigrants, today the neighbourhood is home to migrants from the country's nine provinces and the continent's almost countless countries. People converge on the streets at all hours – an exception in a city where many residents lock themselves behind metal gates, electrified fences and razor wire-topped walls before the sun sets. It is a place feared by many, wealthy or poor, white or black. It has become a metonym for all the dangers many believe immigrants import into the country: drugs, violence, prostitution, degradation, lawlessness, corruption. But it is also where tomato sellers and labourers share the streets with students, children and hustlers trying to feed their families and their aspirations.

Just 50 kilometres to the north is Pretoria, apartheid's former political nerve centre. It too is being transformed by people from across the country and the continent. Whether in the inner city, Sunnyside, or the townships of Soshanguve or Mamelodi, South African migrants live and work side by side with long-term residents and new, international arrivals. Together Pretoria, Johannesburg and the municipalities surrounding them make up the Gauteng City Region, a mega-city positioning itself as the economic pulse of Africa, abounding with promise and opportunity.

For authorities, the arrival of immigrants and migrants often threatens their hopes for a prosperous, orderly ‘world class African city’ – the marketing tagline once adopted by the City of Johannesburg.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- I Want to Go Home ForeverStories of Becoming and Belonging in South Africa's Great Metropolis, pp. 1 - 17Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2018