Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- 5 Hogarth Engraving

- 6 Lithograph

- 7 Morse Telegraph

- 8 Singer Sewing Machine

- 9 Uncle Tom's Cabin

- 10 Corset

- 11 A.G. Bell Telephone

- 12 Light Bulb

- 13 Oscar Wilde Portrait

- 14 Kodak Camera

- 15 Kinetoscope

- 16 Deerstalker Hat

- 17 Paper Print

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- About The Contributors

10 - Corset

from The Age of invention

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- 5 Hogarth Engraving

- 6 Lithograph

- 7 Morse Telegraph

- 8 Singer Sewing Machine

- 9 Uncle Tom's Cabin

- 10 Corset

- 11 A.G. Bell Telephone

- 12 Light Bulb

- 13 Oscar Wilde Portrait

- 14 Kodak Camera

- 15 Kinetoscope

- 16 Deerstalker Hat

- 17 Paper Print

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- About The Contributors

Summary

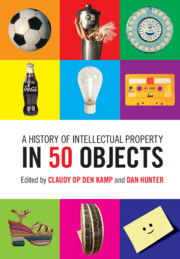

TWO CENTURIES AGO, women and girls throughout the United States reached for one piece of technology first thing in the morning, and kept it with them all day long—the corset. Although men had worn corsets in earlierperiods, the corset's purpose by the mid-19th century was to create the public shape of the female body. It emphasized (or depending on the whims of fashion, deemphasized), bust, waist, and hips in ways intended to accentuate differences between male and female. Today, the corset still fascinates, an emblem of fem-ininity that appears on fashion runways, the concert stage (famously worn by pop star Madonna), and in blockbuster movies (THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW, GONE WITH THE WIND). Less visible are the ways the corset as an object of intellectual property has exposed the masculine assumptions in our understanding of technology, patents, and law.

When we think of technology, we think of machines, not underwear. This understanding of technology is the product of the Industrial Revolution. The development of factories separated mass-produced technologies from home-made technologies. As women's work remained home based, “technology” became something made, and better understood, by men. The results of that gendering have been profound, reflected in the gender gap in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) participation, and the wage gap between men and women in industrialized nations, as women's work outside the home was less valued.

Patent laws drafted and interpreted in the 19th century helped reinforce the masculinity of technology, invention, and inventors by the legal definition of “invention.” To this day, an innovative, collapsible playpen made by a carpenter or in a factory can be patent-protected; a baby quilt made in a novel design, stitched lovingly at home, cannot. In the golden age of invention, the famous inventors were men, like Samuel Morse, Thomas Edison, and Alexander Graham Bell, all patent-holders. By one count, women obtained fewer than 100 patents in the United States before 1860, and while the number of female patentees increased significantly after the Civil War (1861-1865), less than one percent of late 19th-century patents were granted to women.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects , pp. 88 - 95Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019