7.1 The Visible Story

Agra is the north-Indian city famous for the Taj Mahal. But beyond the beautiful structure of the Taj lie swathes of ‘unstructured’ markets of a particular item that Agra is more famous for in the local context – shoes. Agra is the most important centre of (leather) footwear manufacturing in India, and has remained so for centuries. The city produces for about 55 per cent of the Indian domestic markets and 22 per cent of total footwear exports from India (Hashim, Murthy, and Roy Reference Hashim, Murthy and Roy2010). Around 40 per cent of the city’s 1.7 million people are directly or indirectly involved with the footwear industry. The National Sample Survey Office (a government organization that collects large-scale sample surveys in India) reveals that Agra fares second in the share of population that is self-employed.Footnote 1 A good reason for this is the massive footwear cluster it has had historically.Footnote 2

While there are huge export houses and medium-scale businesses, an overwhelming majority of work takes place in households, with traditional artisans making shoes by hand. These shoemaker artisans (also called dastakaar), who work in their homes with their family members making shoes by hand and selling their produce the next day in the wholesale market, employ a significant part of the city’s population. By some estimates, more than two-thirds of manufacturing units are located in household artisan-dominated communities (Knorringa Reference Knorringa1999b). According to some estimates, around ‘50,000–60,000 production workers, employed in around 4,000–5,000 mostly informal small-scale manufacturing units would produce approximately 300,000 pairs of shoes’ (Knorringa Reference Knorringa, Pedersen, Sverrisson and van Dijk1994: 311), although these have significantly increased in last two decades.

The wholesale market in Agra is called Hing ki Mandi. It is a huge, bustling bazaar with hundreds of trading shops and small factory units where artisans come in the evenings with carts and rickshaws laden with shoes to sell. These wholesale shops are run and maintained by traders. Every day, the bazaar comes alive in the evening, with hundreds of shoemakers and traders busy haggling, negotiating, and finalizing prices, and in parallel are sights of loading, unloading, and hundreds of people chatting away. In a matter of a few hours, transaction worth millions of rupees will have taken place in one of the most congested markets one can witness.

A closer look reveals something interesting. Traders buy the footwear but do not make the payment upfront. They purchase shoes on credit. This credit is passed on to a wholesaler in another city, or a retailer. The retailer further buys the shoes on credit. Only when the retailer has made some sale, and received cash from customers, will he fulfil his debt to the trader. And only when all the traders in this supply chain have been paid, will the shoemaker receive his payment. Typically, traders ask three months’ credit from the shoemakers.

Businesses around the world run on trade credit. That is not new. But there remain two issues that encourage me to pry into this market further. Firstly, how do traders offer credible commitments to the shoemakers, namely why do shoemakers trust the traders’ promise. Secondly, trade credit is offered by shoemakers whose cost of liquidity is very high. They need cash today to buy raw materials for making tomorrow’s shoes. How do they access capital for themselves today if the trader pays in three months?

The fieldwork (both participant observation and unstructured interviews) for the study took place between December 2012 and January 2013 and during April–August 2013. I sat in two of the traders’ establishments during the day for several weeks, in order to observe how the trade works. This way, without divulging specific financial knowledge, they explained the trade business. My initial understanding of the market emerged through interviews with six traders. These traders took extensive time to explain the functioning of the shoe market, its structure, dynamics, and history. Two of the traders had worked in the market for more than four decades and all of them were second- or third-generation traders. With each trader I had around four to five sessions lasting on an average between one and two hours.

During my stay in the footwear cluster, I met 27 traders, 45 shoemakers, and 4 intermediaries. The meetings with shoemakers were in larger groups, while the meetings with traders and intermediaries were one-on-one. My observations in the footwear cluster were rather consistent over the months. I validated my impressions by repeated conversations with different actors. This validation was further achieved by few unstructured interviews I conducted with those outside the market (with a banker, an industrialist manufacturing footwear packaging, three journalists in local newspapers of which one was a veteran), but with deep knowledge about the market and its actors. During off-days (Mondays), I had the chance to visit shoemakers at their homes and chat with them informally. This intimate setting allowed me to collect richer narratives. Many of these conversations took place with several shoemakers sitting together at one house. I had three of those collective sessions, each lasting about an hour. In these private settings the coherence of my impressions was underscored.

Finally, I met with the leader of the association of shoemakers, where shoemakers informally convene to discuss their business. He explained to me in greater detail the government’s and banks’ disengagement with the artisans/shoemakers and often lack of understanding and support at the public level. Questions of caste and politics became important in this conversation. In 2011, the association of shoe traders produced a list of 446 shoemakers in the market that year, which was made available to me. Through one trader and one intermediary (aadhatiya), who had several decades of experience in the market, I compiled the discount rates of these traders to get a sense of overall market discount rate. The responses from the two respondents yielded small deviations so qualitative conclusions could be drawn with confidence. With the help of that list I could determine the average discount rate of 312 traders, since not all of those in the list were prominent.

Through my fieldwork I discovered that the problem of informal trade credit is solved with the help of an institutional artefact, the parchi, which literally translates into a paper-slip. When shoes are sold, the trader takes out a parchi, which bears his name, the amount due and the payable date, and hands it over to the shoemaker. The parchi is signed by the trader, and the understanding is that when his parchi is brought to the trader on the mentioned date (which is usually three months later), the trader will pay the said amount. He will pay his debt obligation to whoever brings him the parchi on the due date. Every trader makes such a promise. With sufficient trust in the market (which I discuss below), this aims to solve the problem of credible commitments.

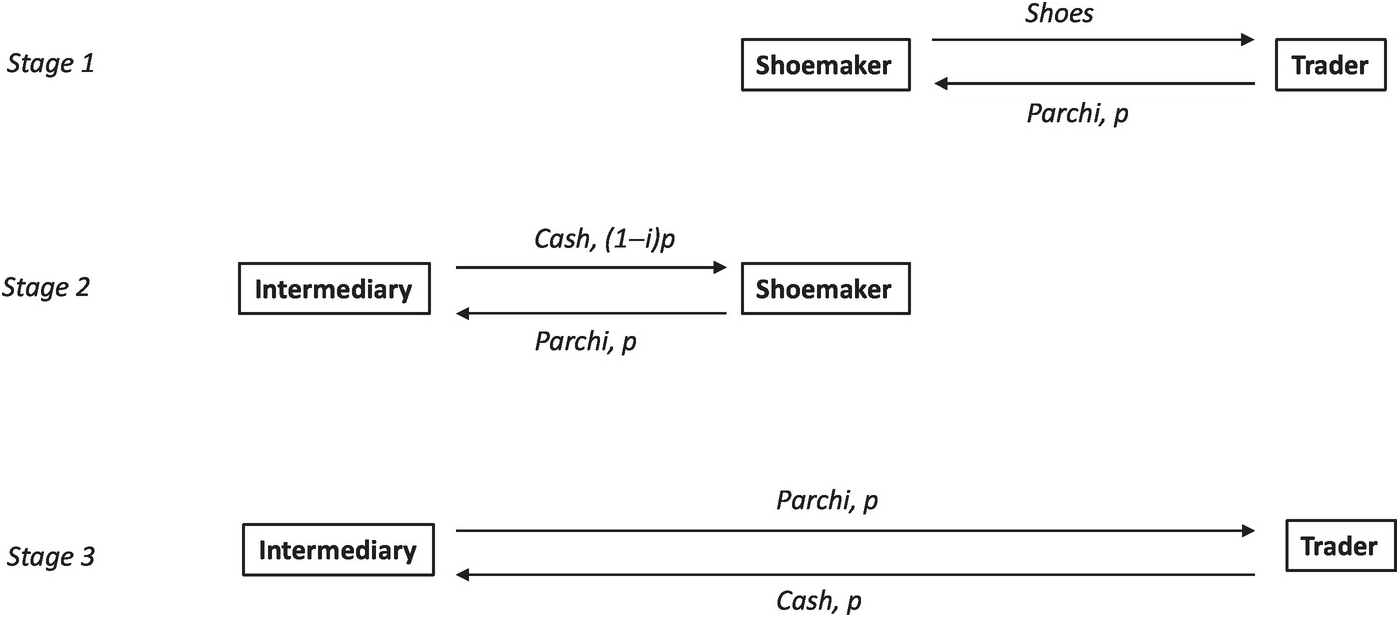

How does the parchi solve the problem of liquidity? This is done because parchis assume the status of a promissory note, a negotiable instrument, informally within the market. Informal intermediaries have evolved in the market, known as aadhatiyas. They buy the parchis at a discount. On the due date, they go to the trader whose parchi they had purchased and claim the amount. They earn the discount, the shoemaker gets his liquidity and the trader gets his credit. This structure is illustrated in Figure 7.1. In many cases, the parchis act as currency as well, when shoemakers can buy raw materials in the market through a parchi – again at a discount.

Figure 7.1. Transfer of credit in Agra footwear industry. p denotes value of parchi and i is the discount rate of the parchi that aadhatiya (intermediary) charges the shoemaker.

One may wonder, what is the discount rate? It depends only on the creditworthiness of the trader. If a trader is known to delay his payments or renege on his parchi promise, his discount rate would be high. For those with high trust ratings, discount rates are lower. And since shoemakers want to sell the shoes to a trader with low discount rates, they will go to the most trustworthy ones. This means, if a trader wants to attract good shoemakers, he better be trustworthy, and have a record of payment in time.

My primary survey revealed that the mean monthly discount rate is 1.41 per cent, ranging from 0.75 per cent to 3 per cent. This annual interest rate of about 17 per cent is almost 5 per cent points higher than the bank’s interest rate. But people don’t go to the bank. Even in moments of disputes, the local association of shoe traders arbitrates. These are community elders who have also been successful shoe businessmen. They will draw from their own experience, integrity, and knowledge of the market participants.

7.2 The Invisible Infrastructure in the Story

Surely, this complex and delicate institution could not exist without an appropriate, advanced, and elaborate infrastructure of norms and knowledge. An institutionalized sharing of resources between the community members is essentially the idea behind commons (Madison, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Madison, Frischmann and Strandburg2010: 841). This governance method itself is a kind of knowledge that is driven by formal and informal rules and norms. It becomes important to examine what holds informal markets in such high state of trust that without the means of any legally structured contract or property rights regime, market participants are able to engage with each other and constantly negotiate their positions with respect to market institutions? How do they know what rules, infrastructures, and artefacts (for instance, interest rates) are in place and when and how is it changing? How do they create and simultaneously use this knowledge? If this knowledge is a resource, how is it governed and arranged? Is the absence of any anxiety on the part of market actors in the uncertain environment they operate, any indication of some form of culture that prevails in this market? How is the knowledge and culture shared, consumed, and absorbed?

Through the example of Agra’s footwear cluster case, I observe the invisible socio-cultural infrastructure,Footnote 3 which helps me theorize on the instruments of classifications and interpretations done through a shared knowledge resource.

7.2.1 The Nature of Product

The shared knowledge of creditworthiness is the crucial resource that is used by market participants to allocate credits and discount rates. This creditworthiness – and consequently the discount rates on parchis of each trader – is the product in question. It is produced and consumed simultaneously as knowledge commons by an intricate network of knowledge-sharing mechanisms like gossip, rumour, and everyday interactions. Presence of this close-knit network – both physically as well as psychologically – allows a great deal of flexibility in the markets, at the same time arresting an otherwise expected uncertainty in a decentralized credit. The product is produced by physical presence in the market, by chatting away with hundreds of people every day, by closely observing the traders and their public (even private) dealings. Since creditworthiness cannot be directly observed by looking at traders’ bank account details (anyway most of the trade happens in cash), market participants must rely on a range of other variables that act as useful proxies for the product.

For instance, knowledge of trader’s financial health, his social relationships, his record of past promises, his reputation in the market, his ongoing trade deals, and so on become important. But also important are floating knowledge details on traders’ exposures to high debt, business health, their future contracts, inventory size, downsizing processes, purchase of a new machinery, sale of their plot of land, and family marriages (girl’s marriage as increasing liability and boy’s marriage as enhancing asset provided the bride comes from a rich family). News of, say, cancelling of a large order or important meeting abroad or participating in a trade fair will also become crucial. Factors that affect a trader’s financial health are embedded in their day-to-day functioning both within and outside the market. It depends on their linkages and relational associations that they may have. Therefore, knowledge about a trader’s personal life and that of his debtors and creditors becomes paramount to keep an eye on his financial health. This type of information sharing also means that rumours could be risky. Hence, market participants have to be extremely cautious about anything they do in the public domain, lest a fake news is spread.

Further, since every action of the market participants (particularly the traders) is being observed, they do not want to be caught engaging in what would otherwise be morally repugnant. Whatever the market participants do must have a cultural sanction, because moral judgements carry strong bearing on one’s character, and consequently one’s creditworthiness. For instance, market may not take kindly to a trader who is known to have, say, thrown his old parents out of the house. Scholars have shown extensively how morality and markets have often intersected on cultural junctions (Fourcade and Healy Reference Fourcade and Healy2007). The various mental models and even social artefacts of culture become useful components of the social infrastructure on which knowledge commons breed. It deters them from engaging in activities which are socially undesirable. And since what is socially undesirable keeps changing with times, this knowledge is also dynamic in nature.

And extraction of this knowledge is possible by self-presence and absorption of tacit knowledge (Polanyi Reference Polanyi1966) through ‘being’ in the market and network. The close-knit community ensures near-to-perfect information symmetry. There is very low likelihood of misinterpretation because the tacit knowledge for market participants here locates within existing mental models that are formed over time. And as the knowledge is produced, it is quickly shared by participants, through word-of-mouth. As soon as the news of discount rates spiking up reaches one person, almost everyone gets to know about it. The more the word spreads, the more certainty this knowledge assumes. In consuming this knowledge, people produce it. This means, unlike a physical resource (Klamer Reference Klamer2017), this knowledge commons is anti-rival. When the knowledge commons on creditworthiness is produced, it enhances its value and often transforms its applicability as and when more and more people use it. As Hess and Ostrom (Reference Hess and Ostrom2005) illustrate the concept of contribution to a shared resource, I see the market participants in Agra’s footwear cluster do the same – they have the right to change the content of the resource, and add or remove knowledge attributes that yield various layers of the knowledge about creditworthiness. The interesting thing is that the change in the shared knowledge resource of creditworthiness can be triggered by anyone. Everyone safeguards the shared resource collectively.

This information readily hovers in the market within the participants but will be extremely difficult for an outsider to collect. Incremental elements of the knowledge will be worthless for someone who does not have the cumulative knowledge endowment. Consequently, non-market actors, from outside, usually would not have any bearing or the right to change the knowledge commons. Such an exclusion is seen simply in the shared knowledge of community networks, group (caste, as shown later) loyalty, and continuous interaction between the market participants, and not the outsiders.

All of this means that the knowledge structure of creditworthiness is built on a range of shared knowledge pillars. Put together, the entire volume of knowledge commons is shared and used by market participants every moment while they are in action. The value of this resource is dependent on the value of the entire socio-cultural infrastructure that makes the shared resource valuable (Madison, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Madison, Frischmann and Strandburg2010: 689; Frischmann Reference Frischmann2012). But such an infrastructure itself relies on various technological features that enable governing the knowledge commons.

7.2.2 Enabling Technology

The shared understanding of various items mentioned above forms the inventory of socio-technical imaginary that enables the knowledge resource to be shared and utilized in the market. A valuable platform in this context – to establish credible commitments – is the high level of information symmetry in the market. Almost every market participant knows every other participant, and news of non-payment (or delayed payment) spreads fast. If a trader reneges on his payment, this is quickly known in the entire market (even to stakeholders outside), through informal channels of information dissemination in the form of discussions, gossip, chats, rumours, and informal gatherings. The market is very cohesive and close-knit; relational and trust-based conversations are invoked in everyday transactions. This builds a fertile environment of reliable tacit knowledge (Goyal and Heine Reference Goyal and Heine2021). Such tacit knowledge develops as knowledge is inherently created by those who use it. Its amorphous form also makes the exercise of putting the contract onto paper meaningless. Those within the market cannot escape it anyway, and those outside cannot acquire it easily.

The group cohesion becomes stronger because of the Indian caste system (explained in the next section). Most traders come from the Punjabi community, while artisans and workers are either Muslims or belong to the backward castes (Jatavs). If one looks at their dwelling pattern, traders reside in certain premium locations in Agra (like Jaipur House), and hence they meet often during local social gatherings. They have conjugal alliances and are members of the same city clubs. The artisans live in ghettos and after work they get together for local drinks and food. They share stories, rumours, and build and disseminate information. Idiosyncratic knowledge develops from within the community and dynamically alters itself through these gatherings. The convergence in interpretation has brought about the tacit knowledge structures, shared by the community and which are characteristic features of the marketplace experience. If the news of a trader not paying his dues or having a contract cancelled is revealed to one of them, in short time almost every shoemaker will know about it. The market allows everyone to keep a keen eye on the worth of the traders. Hence, if a trader issues parchis higher than their estimated worth, artisans receive the alert instantly through gossip and street rumours.

This allows us to see the physicality of space through an analytical aperture. The fact that the market is physically a cohesive space (note more than 3–4 km2), coupled with the interwoven habitats in the localities participants live, makes the shared resource produced and consumed easily. Participants benefit from the tacit knowledge by simply being physically located around each other. A videoconferencing or remote access to information is of no use. The physicality of the shared infrastructure is the reason market participants are able to draw the resource much better than a bank or another financial intermediary located outside. Cultural resources are distributed spatially, and cultural experiences are linked with accessibility and proximity (Cohen Reference Cohen2007). Since the social infrastructure is culturally embedded (Frischmann Reference Frischmann2012: 256), this part of knowledge commons governance – as visible in Agra’s case – must be recognized.

The shared resource relies on a certain type of social infrastructure in order to cultivate itself and grow.Footnote 4 Formal markets have written laws that enable, inter alia, shared goods to be reproduced and utilized. Laws often act as normative coordinating points around which people converge their behavior through a shared understanding of the law (McAdams Reference McAdams2015). In the absence of written formal laws, people discover or invent normative private orders, which may or may not be as efficient as a formal legal order. Nevertheless, absence of formal order does not mean transactions will take place in an institutional vacuum. New normative orders will develop. The informal footwear cluster in Agra does the same. Shared resources draw from an inventory of social infrastructures constructed on the edifices of shared understanding of caste, familiarity, hierarchy, group-loyalty, conjugal alliances, social embeddedness, gossip, conversations, cohabitation, informal rules, norms, beliefs, and many such aspects. These attributes construct, consume, and coordinate the shared pool of knowledge as common good. They allow interdependencies that go far beyond just the agreement on price; they share a variety of expectations, which is possible through the tools offered by the social infrastructure in place (Kuchař and Dekker Reference Kuchař and Dekker2017).

All of this social infrastructure – in addition to various other artefacts that I discuss below – exists in the form of a knowledge commons. It acts as a cohesive social glue that is manufactured in the everyday interactions and community characteristics. Agra’s footwear cluster not only produces shoes but also jointly produces the infrastructure that makes shoe production possible. It is able to do so through a sense of coherence manifested in the beliefs, ritualistic negotiations, observance of reciprocity, formal rules and shared knowledge about the product, and various other characteristics of the knowledge resources. North’s imagination of structuring interactions comes to mind (North Reference North1990). The social infrastructure is indeed the key resource which ensures that the shared good is a common resource, and that it is produced and consumed – and in consuming, further produced.

7.3 Plugging the Story in a Framework

Elinor Ostrom has offered theoretical beacons that can shed light on the designs of institutions which govern the commons (Reference Ostrom1990, Reference Ostrom2005). Her extensive work across the world (for instance, lobsters in Maine, high meadows in Switzerland, forests in Sri Lanka, fisheries in Alanya, Turkey, and water in Nepal) helped her design a framework that can potentially explain the commons governance at a general level. The framework – known as Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework – offers a very effective toolkit to understand community managed resources.

If knowledge is a common resource in question in Agra’s footwear cluster as I show above, perhaps the IAD framework may illuminate my case as well. Just as Ostrom thought of tangible resources like lobsters or fish, one can think of intangible resources, like knowledge. But the two products are not the same, exactly. For starters, lobster fisheries are rival resources and may get depleted by overfishing (for argument’s sake). Knowledge, on the other hand, would not; on the contrary, it will grow with more consumption. In that it will be anti-rival. Further, the lobsters occur naturally and are truly exogenous. Knowledge, on the other hand, is produced by the consumers themselves, displaying an interplay between them (as well as the rules which emerge out of the manner in which community produces and consumes the resource). One may say that the knowledge, in many cases may not be cumulative as in lobsters because of the heterogeneity of the product or service at hand. In that sense, it could be a specific kind of situational knowledge that must be appropriate for the stock of knowledge to ‘grow’ meaningfully. Regardless of this – and I need more space to dwell on this question – the IAD framework must be appropriately tweaked to incorporate a new type of resource: the knowledge commons.

This tweaking must absorb such social infrastructure which becomes the bedrock for informal markets to emerge and persist over time. This has been done creatively in Madison, Frischmann, and Strandburg (Reference Madison, Frischmann and Strandburg2010), which I draw on. The authors examine patent pools, open source software, Wikipedia, Associated Press, medieval guilds, and modern research universities to show how Ostrom’s framework can be suitably modified to capture knowledge as a commonly held good. I attempt to locate the case of Agra’s footwear cluster in the same modified-IAD framework.

Two modifications of the IAD framework encourage me to use that framing. Firstly, in the modified framework, the resource characteristics (biophysical features), community attributes and rules-in-use continuously co-evolve, rather than existing as three separate exogenous variables. In other words, the independence and exogeneity of the three variables is suspended. In the context of knowledge commons prevalent in informal markets like Agra’s footwear cluster, as I show, I observe that the three variables co-produce each other. They are also continuously fed from the patterns of interaction, as is the provided for in the modified IAD framework. Secondly, the distinction between patterns of interaction and the outcome is collapsed. The patterns of interaction in market resting on social and cultural infrastructure are itself the outcome which will be used as one of the inputs in manufacturing and consuming the resource.

We have discussed the resource characteristics in the preceding section. It is also clear why patterns of interaction would be the outcome itself, feeding back into the resource creation and usage – it is through gossip and endless chats and conversations that the knowledge resource of creditworthiness gets created, and it is through the community attributes that the conversations take place the way they do, under the rules which are drawn based on community networking in the first place. This knowledge about the creditworthiness is interrelated and dependent on the patterns in which informal contract and property rights are recognized, and which explain who can sell and be part of the transactional frame. I shall now examine the community attributes and the rules-in-use to help theorize the idea of governing knowledge commons, particularly in cases of informal clusters that are hinged on some shared knowledge to sustain and evolve, and in doing so, help locate the suitability of the modified-IAD framework for examining our case.

7.3.1 Community Attributes Folded in Culture and History

Hess and Ostrom (Reference Hess and Ostrom2005) propose that for any self-organized commons to be successful, in addition to collective action and self-governance, what is really needed is social capital. These again form part of the social infrastructure. This means, then, that knowledge commons may have a strong cultural construct. Evolution of any marketplace relying on informal social norms will exhibit development of social infrastructure over time, which in turn ought to explain the community attributes. These attributes become part of the functional identity through which the resource gets produced and disseminated. Knowledge remains nested in the social relationships. It is therefore culturally constructed.

Cultural constructions take time to build. Hence, understanding the evolution of the market through history offers a useful starting point to appreciate the social infrastructure in place, which enables the patterns of interaction to feed back into the resource, community, and rules. As Hall and Jones (Reference Hall and Jones1999) have shown, historical design of social infrastructure is crucial to understand economic performance in the long run. I show that through history, caste dynamics and their skillsets become necessary community attributes, and this in turn evolves the market and its interactive patterns in the way they are manifested today.

Hindus are generally divided into several castes, vertically and roughly segregated on the basis of occupation. Work on dead animal’s hides or leather is considered polluting and forbidden to upper castes (Khare Reference Khare1984). Hence, historically, leather goods could be made mostly by Muslims and a particular lower caste called the chamars (also called as Jatavs). Only those born as chamars could ‘occupy the status of shoemaker without breaking caste rules’ (Lynch Reference Lynch, Singer and Cohn1969). Agra has had a huge Jatav population (as well as Muslims) historically,Footnote 5 and during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Agra was the capital of Mughal dynasty, which was a great connoisseur of art, craftsmanship, and embroidery – as well as leather footwear. Availability of skilled labour and high demand from the elites led Agra to assume importance in leather footwear making. Later, the British brought in English designers and enhanced the skillsets of the artisans in Agra, which was the capital of one of their provinces for a good part of the nineteenth century. At around 1900, in fact, the first central shoe market was set up in Hing ki Mandi, which facilitated the trade significantly by allowing wholesale traders to sit at one place where both manufacturers and other merchants could come directly (Knorringa Reference Knorringa1999b). My interviews with local elders reveal there was no parchi system at that time since the market never needed any. But more interestingly, I learn that the artisans would occupy specific localities and work used to happen in clusters of neighbourhoods. This is something we still see today. And as discussed in the preceding section, the physicality of the presence of participants together generates a cohesiveness which enables sharing the knowledge resource.

The India–Pakistan partition, which took place in 1947, uprooted around 30 million people on both sides, in one of the largest displacements in recent human history (Bharadwaj, Khwaja, and Mian Reference Bharadwaj, Khwaja and Mian2008). A good part of Agra’s Muslim footwear merchants migrated to Pakistan, leading to a decline in the shoe industry in the city (Knorringa Reference Knorringa1999b). At the same time, the city saw a huge influx of Punjabi migrants from the other side of the border.

Punjabis, usually Hindus or Sikhs, however, do not observe the strict forms of caste-based segregation. Consequently, they have no qualms working with leather. They observed the market flooded with skilled craftsmen and quickly became their commissioning agents. Slowly, trust began to develop between Punjabi merchants and Jatav shoemakers. This trust and close-knit cohesiveness built knowledge structures about each other, tacitly produced, enriched, and shared between the parties. Migration led to various community interactions that led to the emergence of new forms of trade. Punjabis were migrant communities, and remaining closely knit was a social necessity. Old records of their settlements in Agra don’t exist, but urban patterns of their dwelling show homogenous, affluent, gated communities in which Punjabis, Baniyas, and other upper castes live together. In the same way, Jatav artisans live in poor ghettos of the society. Sticking with each other, and working in the same cluster, trading communities gather idiosyncratic knowledge by virtue of their presence in the market. This physicality was indeed crucial to build the initial level of trust.

This trust, slowly enabled credit to emerge in the market. Punjabis began purchasing shoes from Jatav artisans on credit. They would sell them off in markets outside Agra, give the shoemakers their due and keep the rest for themselves. The only difficulty was remaining penny-less for the first round of the cycle. Once the second round began, the chain of credit was triggered. This led to the emergence of early signs of parchi system in the industry.

Perhaps another factor led to the creation of this institution, and that is, the caste system itself. Note that Punjabis occupy a much higher status in India compared to lower castes. Jatavs, at the bottom, could easily have been subdued by the higher cultural and feudal status of Punjabis. Punjabis could have garnered various forms of caste-based subservience from lower caste people and ‘used’ Jatav artisans. Bremen (Reference Bremen1974) observes the caste-based societies in India and identifies that both patronage and exploitation often coexist in such places. Indeed, records suggest that the pre-partition relations between Muslim distributors and Jatav producers were ‘smooth’ and amicable (Lynch Reference Lynch, Singer and Cohn1969: 36). The former would purchase shoes in cash and also give favourable loans to Jatavs. All this changed when Punjabis replaced Muslims after the partition. Punjabis’ approach was much harsher and more antagonistic towards Jatav artisans (Knorringa Reference Knorringa1999b). Using their institutional power of caste, Punjabis, over time, expanded the markets through credit.

Be that as it may, creation of the institution of parchi was hinged on the community attributes which enabled certain type of characteristics for the resource to emerge. Physicality and the caste-system are two useful takeaways. The community attributes are very clear in terms of their identity, in terms of castes that occupationally segregate them. Such types of community attributes therefore can be seen to give rise to certain form of knowledge sharing to happen automatically. When knowledge is used as a resource, the governance of that shared knowledge evolves around the same community attributes which helped trigger its production. The consumers, producers, and coordinators of the knowledge are the community, through their own characteristic features that developed historically.Footnote 6 We can observe this in the way participants discriminate prices, discount rates, and, most importantly, switch between traders. The shared infrastructure allows for an extremely low level of loyalty between artisans, traders, and intermediaries, but at the same time, a very high level of loyalty within the market as a whole. The social infrastructure in this case was historically as well as culturally constructed. Such a construction crystallizes the community (cultural) attributes which also enables certain rules to evolve. And it is the combination of the community and the rules that effectively utilizes the resource in question.

7.3.2 Salient Features and Rules

Market in Agra and, more specifically, the trade credit institution in the market, as we have seen, was not a purely natural or a purely artificial construction. It was born in the cultural intercourse that happened as a result of friction between different communities engaging with each other. And the community engagement led to peculiar and complex rules to emerge in the market. In fact, Karl Polanyi (Reference Polanyi1944) has remarked how trade is an external affair between different communities rather than the same tribe. The story of Punjabi–Jatav interactions triggering a new layer of trade explains this vividly. Trading with strangers would have required new intellectual and legal infrastructures and new tools, which are indeed visible today. It also encapsulates the general order of how things work in the market with respect to trade credit, and centralizes the importance of trust, reciprocity, and various forms of monitoring and sanctions, as illustrated in Dietz, Ostrom, and Stern (Reference Dietz, Ostrom and Stern2003). This now needs to be understood in an extensive form, that is, what these rules are used for and how they achieve the purpose.

The real aim for which rules-in-use are to be conceptualized here include continued production of shared knowledge, reducing transaction costs to access and use it and ensuring the accuracy of the knowledge resource. Production and dissemination of the knowledge commons happens through continuous engagement of the communities amongst each other, manifested in their daily interactions, gossips, rumours, and being part of the market. The continuous engagement helps screen accurate from inaccurate knowledge. Since any new piece of knowledge goes through the test of confirmations, with dialogical testing, it will die out soon unless it can be validated and re-validated through the market participants in their regular conversational use. When the knowledge may pertain to an actor in the market, he is incentivized to arrest spread of any untrue knowledge. Beliefs aside, an untrue knowledge, without being continuously tested and legitimized, soon dies out. In addition, caste-based loyalty enforces the spread of rumours, news and other such material information that then gets carried far and wide and takes the shape of a templatized form of discount rates.

The rules-in-use, therefore, underscore respecting promises of parchi, which acts as a promissory note, credit rationing, dispute resolution, and imposing multilateral punishment strategy. Perhaps the most important is the idea of keeping promises. When a trader issues a parchi, his reneging is sure to attract penalty and this disciplines the market to observe the promise. It is such a strict rule that the market has practically no sympathy for any delayed payment, no matter the reason behind the delay. The day of the payment witnesses massive exchange of cash between traders because they have no qualms in borrowing money to pay off their dues on the payment date. In one of my interviews it was revealed that on the day of the payment, even if a dog comes to the trader with his parchi stuck in its mouth, the trader will take the parchi and shove the money in its mouth.

Actors make their own networks, operate within, and rely on their own caste and community networks for accessing the knowledge commons, and reusing it to share with others. Punjabis do it amongst themselves, Jatavs in their own community and so do the intermediaries. And since all of them talk to each other, there is hardly any difference or arbitrage in the knowledge commons. The caste networks bring them closer – they all share stories, rumours, gossip, and build information within their respective groups. This also puts one group against the other. The usual narrative among the traders is that the shoemakers are a lazy lot and they spend their money in gambling and drinking. The other group laments how traders exploit them, squeezing them off any surplus. This makes each of these groups loyal to each other.

The rules-in-use have also evolved on the manner in which trading on some parchi will exhibit credit rationing. This means that discount rates do not keep on rising with increasing risk. Beyond a point, people simply stop dealing with the trader, instead of selling shoes on credit with high interest. Stieglitz and Weiss (Reference Stiglitz and Weiss1981) in their seminal work showed that it will often make sense for the banks to ration credit and not keep on raising interest rates indefinitely, because through this, they avoid adverse selection problems. Something similar happens in the market here. The reputational impacts are strong and any reneging on the parchi payment will bring down the credibility of the trader massively. If this happens more than once, his parchi may simply not run in the market and will lose all value, thereby forcing him out of the credit business. In fact, one can see the traders frantically trying to arrange cash a day before the parchi-payment date, so that none of their creditors have a reason to return. In financial terms, one can see an interesting credit rationing happening in the market.

These rules often guide the manner in which dispute resolution in the market takes place. Cases of bankruptcies are dealt with informal dispute settlement, organized by local associations of traders. These bodies are headed by veterans of the trade who mediate and order how much the creditors need to be paid, assessing the leftover worth of the bankrupt trader. The settlements are not done with documentary evidences but exploit the existing local knowledge about the matter. People know the story and lying is not possible by and to a market participant. Judgements of association members are usually adhered to, and State’s judiciary and courts are seldom invoked. This is also possible because many of the unwritten norms are followed with great adherence. For instance, Mondays are no-working days. Payment days are always the 5th, 10th, 15th, 20th, 25th, and 30th of each month (or the next day if the payment date is a holiday/Monday). These rules are not wavered from, and this keeps everything around them also in a strict normative order.

Running away with a huge credit on your head is very rare. This is because the market runs through family units and those players have relational ties, hence arriving at such an end-game (exit) situation is not very likely. Cheating traders’ sons, sons-in-law, and other relatives still continuing in the market may have to suffer the repercussions. The threat of foregone earnings, not just for yourself, but for your near-ones arrests such cheating tendencies.

More interesting is the multilateral punishment strategy. News of nonpayment spreads like wildfire and discount rates spike up instantly. Regardless of who is cheated, once such a trader is discovered by market participants, almost everyone stops going to the trader. This creates a huge cost to the trader and he would not likely try to dupe anyone. If shoemakers stop coming to him, he will have to rebuild his reputation, which will not only take a long time, but no one will sell the shoes to him on credit. Since this news will become public in the market, arranging for cash to regain the trust in the market could be very difficult. And so the threat of future losses disincentivizes the trader from engaging in any dishonest act. This threat of sanction is similar to Greif’s (Reference Greif2006) conception of multilateral punishment.

7.3.3 The Story Cast in the Modified-IAD Framework

One should now be able to connect Agra’s story to the the modified-IAD framework. Informal markets are rugged petri dishes to observe knowledge commons embedded in a social infrastructure. In other words, we can make considerable sense of how informal markets are collectively governed if we observe their social infrastructure and the knowledge commons associated with it. These infrastructural elements, as we saw, are embedded in the history, society, and culture of the place, in which many aspects of knowledge commons are created by some shared goods, manifested in friendships, gossip, and caste-based structures. And having arrived at this point, I can now swiftly slide some of the routine observations about the social infrastructure that enables knowledge commons governance in the modified-IAD framework.

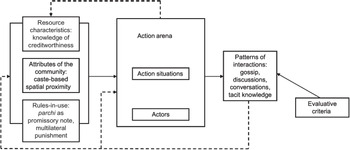

Figure 7.2 illustrates the foundational features of the modified-IAD as it would appear for an informal market like Agra’s footwear cluster. The creditworthiness as the crucial knowledge resource will be a shared, anti-rival resource which is governed like commons. Caste-based loyalty and spatial proximity are crucial community attributes that enable the production, coordination, and consumption of the resource, and corresponding institutional structures have all evolved historically. The rules-in-use are evident in adopting parchis as promissory notes, along with the threat of multilateral punishment strategy (with credit rationing and dispute resolution methods that are not reflected in the figure). Each of these variables – resource, community, and rules – co-produces the other. The knowledge resource exists because the community necessitates its sharing, and that happens through the rules-in-use, which in turn, are by-products of the community’s governance of knowledge commons. The range of interactions, gossip, and knowledge-building exercise which feeds directly into the resource-community-rules collection, themselves act as the outcomes on which the market thrives.

Figure 7.2. The footwear cluster, as located in the GKC framework (Frischmann, Madison, and Strandburg Reference Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014: 19)

Note that looking at the social infrastructure and knowledge commons governance architecture as proposed in the model allows us to understand why this institution of parchi has remained immutable over time. A more formal approach could have enhanced the economic scale of this credit, which would have attracted banks to offer higher credits on lower interest rates. They could have pooled in the risks associated with parchis and offered much better and more voluminous credit instruments. But over several decades, the design of this institution has remained unaltered.

This is because the very social infrastructure that makes knowledge commons governance possible is not easy to formalize. Banks, for instance, simply lack knowledge about the community and are incapable of following their rules. The cost of knowledge for any formal, third party is very high. Knowledge about creditworthiness of the traders is a tacit knowledge embedded within the social infrastructure and known to market actors instantly; securing the information for anyone outside is difficult, including banks. The knowledge of group members, their identity, financial exposure, credit history, social capital, and social embeddedness as valuable repository of the knowledge resource comes easily through the patterns of interaction of the community, which is both the user and producer of the resource. Scaling it up by any formal body will break down these necessary ingredients which make the resource and its use. And should such an effort be considered, it will require an exhaustive understanding of the market to develop some design principles.

7.4 Conclusion

That markets are cultural is not a remarkably new idea. They emerge and evolve within cultural infrastructures. Both Michael Polanyi (Reference Polanyi1958) and Karl Polanyi (Reference Polanyi1944) had argued how economic dynamics are part of larger socially embedded attitudes – a sentiment shared by Karl Popper as well who celebrated open societies to build and share scientific knowledge (Reference Popper1945). The social background is the necessary institutional framework that allows certain types of economic performance and disables the others. Schumpeter was of the view, for instance, that capitalism requires unrestrained democratic space to flourish (Reference Schumpeter1976). Bardhan (Reference Bardhan1989) reminds us of Carl Menger’s (Reference Menger and Nock1883) distinction between organic and pragmatic institutions, where the former are a result of individual pursuits, undersigned, while the latter emerge from conscious contractual design. Both these institutional frameworks inspire heavily, the type of market-based activities that will emerge in time to come. Economic sociology has constructed valuable ideas to explain this as well (Smelser and Swedberg Reference Smelser and Swedberg2010).

It is in this larger context of resuscitating the link between markets and culture that the chapter locates itself. And the necessary theoretical link is offered by the knowledge commons. By looking at the centuries’ old footwear cluster in Agra, and locating its institutional framework in the theory of knowledge commons, the chapter not only empirically tests the theory and surfaces the importance of socio-cultural infrastructure but also advances a conceptual apparatus to understand informal markets from a knowledge commons perspective. If (1) Strandburg, Frischmann, and Madison (Reference Strandburg, Frischmann and Madison2017: 10) suggest that knowledge commons is an ‘institutionalized governance of sharing and, in many cases, creation of … intellectual and cultural resources’ and (2) informal markets are constructed on cultural edifices as I show in this chapter, then it is not difficult to expect knowledge commons framework manifested in a large number of informal market behaviors around the world. And that is why, the generality of the idea cannot be overstated. A vast majority of markets in developing countries operate through knowledge commons, created, and shared on the basis of social, legal, and intellectual infrastructures.

This also calls for a renewed interest not just in informal markets, but also the knowledge commons project. Indeed, if one uses the lens of institutional change to focus on existing informal clusters, one is welcomed by a fascinating array of actors ingeniously producing and consuming knowledge resources to build and rebuild these markets. Knowledge commons are often the building blocks on which foundations of informal spaces are built. And informal spaces employ a majority of the populations in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. Understanding their structure is, therefore, understanding more than half the world.