A thousand burning kisses from your own Winnie.

Thousands of millions of hot, burning, love saturated kisses on all the usual places!

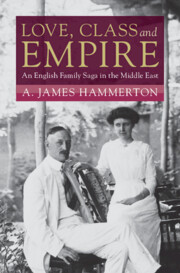

These ‘burning kisses’, sent between a wife in England and her husband in Persia and Iraq in 1914 and 1921, point to the love story at the heart of this book.Footnote 1 Despite their long-term separation and her lone mothering, the mutual passion between Winifred Wilson and her husband, Edgar, hints at the nature of the marriage. Expatriate employment and separation were conditions of married life for thousands of Britons at the height of empire. Status, occupation, and wealth influenced whether couples and families lived together abroad, made regular short visits to each other, or endured long years apart for the sake of the children being educated ‘at home’ in Britain. The English couple whose story is told in this book experienced all these degrees of separation and togetherness, but during their long periods apart they generated a huge archive of letters, which allow us to shine a light on the intimate details of their lives both in the Middle East and England. The letters reveal the details of social and business life, financial hardship and frustrated sexual desire. Such intimate stories are rarely told in conventional histories of imperialism and of British overseas enterprise, yet they belong equally with and illuminate more conventional accounts of imperialism.

The love story is at the centre of the book, but it is an intimate microhistory played out within the rich macrohistory context of an overseas empire and British commercial and strategic enterprise. From the 1880s to the 1930s, the two families behind the couple, the Coopers and Wilsons, lived large parts of their lives, together or apart, in Persia (later Iran), Mesopotamia (later Iraq) and Georgia, then part of Imperial Russia. None of these sites comprised any part of the formal British Empire, but all were a part of a economic and geopolitical power contest. Persia, especially, was central to the British strategic interest of controlling trade, transport and communications with British India. Britain was in frequent conflict with an ambitious Imperial Russia, in what was known as the ‘Great Game’, although at times, as in a 1907 agreement, the influence of the two great powers in Persia came much closer to shared control, something closer to formal empire but effectively part of an ‘informal empire’ for both countries.

‘Other Ranks’ as Agents of Empire

The book’s settings, in various localities in and around the Middle East, were sites where industries vital to British interests, such as shipping, telegraphy and associated trade, could flourish. The historiography of the British Empire has, however, paid the region little more than passing attention, focused largely on its role as a conduit to the real action in British India and the Persian Gulf. One scholar observed that historians of imperialism ‘have tended to ignore the area, or to see its constituent units as parts of another whole – the Gulf as part of the wider history of British India, Egypt as part of the scramble for Africa – or to subsume it under some generalized notion of “the periphery”’.Footnote 2 The book’s main focal points, Persia and Mesopotamia, were subject to varying degrees of British control or interference, qualifying loosely for what has controversially been labelled Britain’s ‘informal empire’, where business interests could be pursued without major obstruction and political influence could protect British strategic interests on the routes to India.

The concept of informal empire has preoccupied imperial historians ever since Gallagher and Robinson published their 1953 article, ‘The Imperialism of Free Trade’, challenging the notion of empire as a system, exclusively, of the direct political rule of colonial possessions. At its broadest, informal empire could encompass a variety of relationships and territories, from manipulation of puppet leaders and flagrant or subtle political influence to benign British support of trading privileges with sovereign states.Footnote 3 Historians’ attention to informal empire recently has focused, in particular, on Latin America, notably Argentina, which enjoyed one of the most intense economic relationships with Britain from the late nineteenth century; indeed, Deborah Cohen described Argentina as ‘the jewel in the crown of Britain’s “informal empire”’.Footnote 4 It was, undoubtedly, a special case; before 1914, it was one of the ten richest countries in the world, accounting for huge proportions of British trade and capital investment, and, after the United States, hosting the second largest British expatriate population outside the formal Empire.Footnote 5

Analysis of informal empire has mostly centred around the politics and economics of trade and investment. To this, we can add an interest in the overseas Britons – individuals and families – engaged in overseas enterprise as long- and short-term residents in formal and informal empire locations, variously labelled expatriates, itinerants and service sojourners – the nomenclature remains unsettled.Footnote 6 Lambert and Lester coined the term ‘careering’ to represent the varied roles of itinerants across different imperial sites, motivated variously by profit, religion or a sense of duty – to which we might add a sense of adventure.Footnote 7 This reflects earlier interest shown in families, those engaged in India especially.Footnote 8 Elizabeth Buettner’s Empire Families pioneered research from private papers on the families of ‘British Indians’, exploring the distinct forms of family life, and family separation, shaped by an itinerant, often multigenerational, lifestyle of ‘permanent impermanence’.Footnote 9

Interest in overseas Britons has stimulated a deeper engagement with life writing, the ‘case study’ and biography as a means of illuminating wider themes in imperial history. It was deployed with particular effect as ‘a powerful way of narrating the past’ in Lambert and Lester’s collection on transimperial networks, although most of the lives examined there and elsewhere until recently were those of elite figures.Footnote 10 This was given added momentum with the British World movement in imperial and migration history, aided often by oral history methods.Footnote 11 The life writing in this book is drawn from the conventional sources of diaries, autobiography and correspondence, together with a later interview. Its focus moves from mobile individuals to family against the background of telegraphy and shipping in the Middle East.

In their research on mobile families, historians have sharpened the gender focus to explore not just how they lived, but also the role of families and women in the larger imperial project, especially in the eighteenth century. Emma Rothschild used a ‘new kind of microhistory’ in her history of the eighteenth-century Johnstone family, ‘minor figures in the public events of the times’, to inform the larger imperial scenes of ‘macrohistorical inquiry’.Footnote 12 Margot Finn’s work on propertied white women’s ‘strategic use of female emotion and sociability’ in the context of the East India Company’s operations, explores ways in which women promoted their families’ ‘wealth status and power even as they nurtured Company children’.Footnote 13

The focus on gender and family in imperial settings is now echoed in research on the informal empire. Deborah Cohen’s work on ‘Love and Money in the Informal Empire’ points the way in her focus on the vital role played by women and family priorities among elite British business expatriates in Argentina. In these overseas merchant families, women’s prominent role in economic activity, compared to their counterparts at home, was matched by the greater priority given to family welfare and relationships over business expansion and national, or imperial, loyalties. Family harmony, before nation and British identity, seemed to be the operating principle.Footnote 14

This book treads parallel conceptual ground to that of Cohen on expatriate populations of the informal empire, but with differences, the most obvious being its setting in the Middle East. Historians’ attempts to bring together work on overseas Britons have rarely included the small but important numbers of relatively transient expatriates east of Egypt. Robert Bickers acknowledged that for his collection, Settlers and Expatriates: Britons over the Seas, he experienced particular difficulty in finding a Middle Eastern case study, such expatriates being deemed to lie ‘beyond the pale of scholarship’.Footnote 15 A second difference is that this book focuses not on elite entrepreneurs and owners of capital but on second-order employees of large business organisations, clerks and administrators who were central to business success, but who met with considerable prosperity and expectations of comfortable settlement ‘back home’, making for a unique story of social mobility. The individuals at the heart of the story came from humble backgrounds, particularly of the upwardly aspiring lower middle class and working-class, dubbed the ‘other ranks of Empire’ by Bickers.Footnote 16 The book explores how they lived in far-flung outposts and how they contributed to commercial and quasi-imperial business operations. It seeks to explore their delicate management of work and family abroad, alongside the blossoming and endurance of love and separation under expatriate conditions. To borrow Emma Rothschild’s term, the book is a further chapter in the ‘inner life of empires’.Footnote 17

The book is also an exploration of the inner lives of expatriates in the process of social mobility. Recently, Peter Mandler reflected on the study of social mobility in Britain, noting its domination by sociologists, who emphasised quantifiable questions such as the relation between education and mobility, while vacating the historical terrain. By contrast, he suggests that historians, with their tools of microanalysis, are best suited to open up the ‘“black box” of motivations and behaviours that may underpin social mobility’. Love, class and empire is, in this sense, a microhistory of expatriate social mobility.Footnote 18

The use of the term ‘expatriate’ throughout the book is deliberate, and best captures the Cooper-Wilsons’ temporary and intermittent work-based mobility. In current usage in migration scholarship, the term has become contentious and racialised. At its crudest, the expatriate has come to represent privileged white mobility, mostly but not exclusively for employment. Conversely, migrants, or immigrants, represent the rest, particularly mass non-white involuntary labour migration.Footnote 19 For the period covered here, in imperial history discourse the opposing terminology is mainly between expatriates and settlers. Crudely again, expatriates, invariably white, moved for expressly temporary work purposes with no intention and usually no opportunity for permanent settlement, while settlers intended to make a permanent home, usually with the advantages of colonisation. On close scrutiny, the distinctions easily break down; for example, expatriates in some informal empire locations such as Argentina often became multigenerational settlers.Footnote 20 This was an option neither desired nor available to our expatriates in Middle Eastern countries. Nor did they label themselves expatriates, a term which never occurs in their writings. They could, though, enjoy a relatively privileged lifestyle away from home, and carry an expatriate and cosmopolitan identity long after their return home.

Two men launch our story: Edgar Wilson, and his eventual father-in-law William Cooper. Both were despatched to Persia, not engaged in government administration but in industries central to British strategic interests. Their employment marked the crucial difference between imperial administration and imperial business.Footnote 21 William Cooper enjoyed a long career in a telegraph company in Persia and Georgia, and Edgar Wilson, who would marry Cooper’s daughter, Winifred, was employed by the Lynch shipping company, agents for the Euphrates and Tigris Steamship Company, plying its trade on the Mesopotamian rivers and in Persia the Karun River, a Persian Gulf tributary. In these ways, Cooper and Wilson were, indirectly, ‘agents of imperialism’, contributing to the smooth running of global communications and trade and, eventually oil exploration. Their narrative, a microhistory of social advancement, expatriation, love and family relations, is inseparable from the macrohistory of empire and of social life in Britain. Each informs the other. Equally telling is the story of Cooper’s daughter, Winifred, born an expatriate in Odessa and living initially in Georgia on the Black Sea, later to enjoy the advantages of middle-class residence in Persia. Winifred’s experience illustrates a narrative of female self-improvement which contrasts with the apparent male monopoly on expatriate social mobility. Seizing the greater freedoms available to young girls in foreign postings, she enjoyed a unique education, employment opportunities and responsibilities, developing maturity and self-assurance. Her experiences fitted her well for an unusually equal marriage and for community leadership following her eventual resettlement in suburban St Albans. Men’s upward mobility launched the story, but it was played out equally by expatriate women like Winifred.

Our love story’s overseas location takes us to sites of imperial business which employed thousands of Britons eager for work. Their employment, and its impact on social mobility at home, forms a central theme of the book. It is no surprise that Cooper and Wilson enjoyed mostly successful careers. Expatriate employment, in the formal Empire or beyond, could be lucrative. Much senior overseas activity was undertaken by British elites from elite backgrounds, elite schools, and elite social circles. The propertied families who served the East India Company from the eighteenth century, for example, maintained their fortunes through sustained company loyalty and shrewd kinship patronage and networking.Footnote 22 These elite men of the Empire were mostly born into privilege and power and exercised it at home as well as abroad. But when Cooper and Wilson first travelled overseas, they enjoyed no such privilege. Both came from poorer backgrounds that in Britain rarely afforded the kinds of opportunities and advancement they enjoyed away from home. The history of imperialism, of migration and of global capitalism is full of examples of how overseas employment could work as an engine of social mobility, as it did for Cooper and Wilson. The adage to ‘seek your fortune overseas’ had concrete meaning when Britain was at the peak of her global power. Voluntary migration had always carried a promise of self-improvement and prosperity, but expatriate employment in imperial territories and beyond offered different rewards.

The capacity of global mobility to stimulate social mobility offered benefits to the British across the class structure. The expansion of service in empire bureaucracies was itself a channel for social advancement. The Indian Civil Service, for example, provided employment opportunities for successive generations of financially strapped middle-class and lower middle-class aspirants, offering incomes and retirement pensions, and for some, status, usually well above equivalent positions at home.Footnote 23 Not all ‘servants of the Empire’ made great fortunes, or even rose in the British class hierarchy, but the promise of advancement, elusive at home, remained powerful for aspiring expatriates. Thousands of working-class and lower middle-class men, and to a lesser degree women, found work across the wider world, in armies, navies and police, in railway work, road building, shipping and telegraph construction, health care and in the supporting bureaucracies. Only a few of these enjoyed stellar advancement. Many were serially itinerant, moving from chance to chance, regarded often as the white trash dregs of British global power.Footnote 24 But their employment contributed powerfully to the British economy and labour market, with family remittances boosting domestic prosperity.

Inside and outside the formal Empire, the individual lives of Bickers’ ‘other ranks’ of global business have slowly begun to make their appearance in historical writing. Imperial history has long since moved on from preoccupation with the powerful heroes of the Empire, the Curzons, the Gordons, the Livingstones, those warranting the imposing memorial statues which now occasionally find renewed recognition in acts of popular demolition. Those in the lower status of trade and associated occupations are less well represented.Footnote 25 Some recent work on ‘Empire marginals’ and others points the way towards a history of the lesser known, often an exercise in biography. One of the most telling examples is Robert Bickers’ account of a British Shanghai policeman between the wars, Empire Made Me: An Englishman Adrift in Shanghai.

Bickers’ Englishman was Maurice Tinkler, son of a mostly unsuccessful ironmonger. Enlisting to fight in 1915 at 17, lying about his age, he had worked as a clerk in the Vickers shipyard at Barrow-in-Furness. Facing no better future than further white-collar work by 1918, he enlisted in the municipal police force in the British administrative enclave in Shanghai – a quasi-imperial concession alongside others run by the French and Americans – joining a host of other marginals from working and lower middle-class backgrounds. He experienced a turbulent but profitable career in Shanghai, ending dramatically at the end of a Japanese sword during a skirmish in 1939. His policing role had facilitated an aggressive form of empire fulfilment through his ability to dominate and brutalise indigenous Chinese men and protect white women from imagined sexual threats. His career was hardly conventional or inspiring, but Bickers agrees with Tinkler’s self-assessment that ‘Empire made me’ in ways that would have been beyond reach for him in Britain.Footnote 26

David Dorward’s account of Arthur London offers a quite different kind of expatriate success narrative. London came from a solid middle-class family in Croydon. The Londons were devout Roman Catholics, reduced to ‘bourgeois penury’ by the premature death of Arthur’s wine-merchant father. Two of his sisters became nuns, and a third one a governess in Greece. Arthur supported his mother by working as a clerk for a butter exporter until he seized an opportunity in 1903, aged twenty two, to work for a commercial firm in Southern Nigeria, again as a clerk but at a much higher salary than he could expect in Britain. It was the beginning of a flourishing career, involving a change of employer to Swanzy and Company, an international trading company on the Gold Coast (Ghana). He eventually became their Chief Agent and, on a visit to England in 1906, married Edith Moore, from an established Croydon middle-class family who considered themselves a ‘cut above’ Arthur’s family. This ‘love match’, producing two children, followed a well-established pattern of expatriate marriages, with Arthur and his wife enduring long periods of separation while he worked in Africa and she raised the children at home. By 1917, when he was offered a permanent position in the company’s London office, he was able to buy a property in Hastings and look forward to a comfortable retirement. Tragically, his rise to prosperity was terminated, prematurely, by his illness and early death in 1920, aged 39, during a holiday tour with Edith on her first visit to Africa.Footnote 27

Tinkler’s and London’s experiences offer a glimpse into the diversity of ways that overseas postings could bring rewarding employment prospects for those ‘other ranks’ struggling to find such rewards at home. Each left England from seemingly dead-end clerical jobs, hinting at how expatriate work could stimulate superior prospects for the lower middle class. For much of the nineteenth century, male white-collar workers had been well-known for their low incomes, limited futures and low status. Aspiring to the status of the prosperous middle class, they frequently earned less than skilled manual workers. Their pretensions to middle-class gentility were easily detected and cruelly lampooned, most famously in George and Weedon Grossmith’s The Diary of a Nobody, through the figure of Mr Pooter, the hapless bank clerk, dedicated to comfortable suburban domesticity, yet the butt of jokes at home as well as at the bank. Similar caricatures appeared in the popular fiction of writers like H. G. Wells, George Gissing, Arnold Bennett and E. M. Forster, although each at times could celebrate the same men for their morality, energy and self-reliance.Footnote 28

Mockery of the lower middle class exercised a powerful sway in late-Victorian culture and after, although the targets could fight back. Correspondents from lower middle-class backgrounds were quick to protest and celebrate the dignity of their domestic culture, their hard work and their defence of family values, all of which involved degrees of domestic partnership and companionate marriage between husband and wife. Significantly, too, lower middle-class families were among the pioneers of the striking limitation of family size which set in during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, itself a suggestion of spousal negotiation and partnership. Easy generalisation is complicated by the sheer diversity of what passed for the lower middle class. There were differences in occupation, from clerks and schoolteachers to shopkeepers and commercial travellers; differences of culture, behaviour and speech, as in the working-class, between degrees of the ‘rough’ and ‘respectable’; and differences of educational and cultural attainment, accent, religious denomination and degrees of religious attachment. Career advancement, at least through slow incremental promotion at home, was an expectation for many, but upward mobility for some coexisted with downward mobility and constant insecurity for others. Those who boasted of their superior ‘refinement and culture’ had an eye on distinguishing themselves from their less accomplished neighbours, but they might also have the confidence to seek the uncertain prospects and risks of career opportunities overseas.Footnote 29

One of our two male expatriates in this book, Edgar Wilson, fits the classic mould of lower middle-class struggle and insecurity alongside material ambition. The youngest son of rural schoolteachers, with sparse family funding for extended education, he spent over a decade from age 14 ‘swotting’ in unpromising clerical jobs before moving to the Persian Gulf in 1902 as a junior shipping clerk. His subsequent advancement owed much to the schoolteachers’ family culture of attachment to the pursuit of knowledge, a boon for Edgar shared with his two older brothers, one of whom became a renowned architect and designer. The earnest scholarly atmosphere at home was reinforced by the family’s devout Anglicanism and commitment to a Christian ethos of hard work and duty. For Edgar, despite material hardship, these were the foundations of confidence in his respectability and talent, with little sign of the servile deference so often regarded as a lower middle-class trademark. As imperial and overseas enterprise demanded an increasing and diverse workforce, the more assertive and confident among the lower middle class, like Edgar, were well-placed to satisfy the needs.

Our other expatriate, William Cooper, could lay no claim to white-collar or any other lower middle-class background. He grew up among the poorest streets of working-class Bermondsey on London’s south bank. His father was a rope-maker and his mother, sometimes, a laundress. Career prospects for Bermondsey street boys were not promising. But a working-class drive for self-improvement and preservation of hard-won respectability could nurture ambition. William’s elementary school years were reinforced by regular attendance, and his role as a choirboy, at the local Anglican Church. Working as a telegram delivery boy from the age of thirteen in 1881, he navigated the perils of that occupation for young boys and was judged to be one of the more deserving among his peers in 1885, when he was selected to be sent to telegraph stations on the Persian Gulf as a junior telegraph clerk. This was, perhaps his only stage of genuine lower middle-class status, albeit on foreign soil, before career elevation followed. Again, religious attachment, respectability and a strong work ethic were powerful drivers of social and cultural mobility. These were the qualities that fitted the aspiring upwardly mobile for lucrative expatriate careers.

The lives of these two men enable us to follow the origins and development of global telegraph communications, from India through Persia and Georgia to Britain, and the role of British river commerce in the Middle East during years of momentous change, commercial expansion, and wartime disruption. The more general history of these developments is well known.Footnote 30 It forms a setting for the lives of two expatriate families, and the insights they offer into unexplored aspects of British overseas industry and commerce. We encounter daily life and work habits on remote stations on the Persian Gulf; family life amid a small multicultural community on the Georgian Black Sea coast; a young expatriate girl’s growing up in three countries; social life and courtship among expatriates in Tehran, and life among diplomatic elites and Anglican missionaries in Baghdad after the First World War.

These experiences of physical mobility contributed to the process of social mobility, where we witness the gradual transformation of the identities of our key actors. In imperial history, much is made now of how imperial ‘careerists’ helped to transform but were transformed themselves by the colonised spaces they occupied. Lambert and Lester saw the ‘formulation and reformulation of identities’ in the biographies of imperial careerists as they moved across different imperial spaces and engaged with different indigenous peoples.Footnote 31 Similar processes of identity transformation can be seen here, although Persian and Arab societies, not subject to official colonial rule and heavily segregated, offered less opportunity to engage with local populations apart from business and staff dealings, a further contrast with other informal empire sites such as Argentina. But even exposure to the worlds of local diplomatic and business expatriates would exercise powerful influences on the identities of the Coopers and Wilsons. We shall see how, for William and Edgar, the story of their later lives brings into focus two contrasting models of their masculinity and expatriate identity, one driven by wanderlust, the other by dreams of suburban domesticity, each forged in their experience of managerial life in foreign lands. In this sense, the book offers a testing ground for Robert Bickers’ observation that men’s (and women’s?) expatriate life could spoil them for life in Britain. ‘They’d moved on and moved up, and a return to the certainties of British life and society would have cramped men who had lived well in China.’Footnote 32

Of course, daily life for expatriates varied considerably from place to place, with local culture, climate, urban or rural settings, and the density of local and expatriate communities playing a part. For example, a Persian capital like Tehran in Edwardian years hosted a small, close-knit international community – mostly Europeans and Americans – with social life centred largely around the British legation and the American Presbyterian Church, and, except for political elites, traders and servants, culturally separate from the local Persian population. Young expatriates, for example, telegraph clerks, junior diplomats, and the unmarried daughters of senior officials could experience freedoms beyond those they might enjoy in Britain, not least having cheap and easy access to horse riding and tennis.Footnote 33 For young women especially, expatriate life could create the conditions for independence, with some work opportunities, for example in a telegraph office, while the frenetic pace of social life provided latitude for some unchaperoned activity. Here were generated the foundations of the Cooper–Wilson love story. A young expatriate-born woman, Winifred Cooper, partly educated in England, widely read and multilingual, brought her experience of independence to her courtship and love match with the much older Edgar Wilson, widowed with two young sons. The result was a more equal marriage than was the norm at the time, despite the expatriate imperatives of long separations that forced wives and mothers into periods of de facto single motherhood. Much of the book traces the evolution of this marriage and its later growth in England, including management of children and stepchildren, financial anxieties, extended family relations, religious commitments and heartfelt declarations of love and sexual desire during long periods of separation and celibacy.

The Archive

Our knowledge of the intimate details of family and business life explored in the book would not be possible without the existence of a comprehensive archive, lovingly preserved and organised by three generations of family members. The ‘Cooper and Wilson Papers’, housed in the Manuscripts Department of the British Library, consists of thirty-six volumes of family and business correspondence, diaries, a substantial memoir, lectures, essays, photographs, family trees and other ephemera. The papers extend from the 1850s to the 1980s, with the heaviest concentration on the years from the 1890s to the 1940s which are the focus of the book. Two women, Isobel Howden, the first daughter of Edgar and Winifred Wilson, and Anne Summers, British Library archivist, were instrumental in recognising the value of the papers and, in the 1980s, bringing them together into the current archive. After her mother’s death Isobel carefully collated the papers and sought their preservation, working closely with Anne. She had enjoyed frank conversations with her parents about their past over the years and was able to attach short explanatory notes and commentary where the material left unanswered questions, adding comments from her own memory. I was able to clarify some uncertainties during a recorded interview with her in 1999, four years before her death. She was pleased that her family’s story would finally be told, a vindication of her dedication to the archive’s preservation. There was little in the way of censorship, particularly of the many intimate letters between Edgar and Winifred, and with very few exceptions, their lengthy and frank later correspondence is complete. The business papers are less exhaustive and, in some cases, have been supplemented from other sources. Edgar Wilson’s twenty pages of close-typed recollection, titled by him an ‘Autobiography’ but actually a selective memoir ending abruptly in 1930, over two decades before his death, adds vital information and reflections; without it, many perplexing questions would be left hanging. For family genealogical information I have been heavily dependent on the wide range of census, births, deaths, marriages, and travel information, now gathered under the commercial enterprise of Ancestry.com.

My journey to the expatriate worlds of the Coopers and Wilsons began during a more general research project on the history of the lower middle class in Victorian and Edwardian England. While seeking biographical stories to expand our knowledge of the Mr Pooters, or ‘black-coated workers’, of the English world, a chance meeting with the archivist, Anne Summers, brought about a sharp change of direction. Anne had recently completed archiving the Cooper–Wilson papers and recognised that Edgar Wilson was a perfect fit for my search. A few days with the archive in the Library’s Manuscript Room pointed to quite different research prospects and transformed my history of the lower middle class. Edgar Wilson’s early life did indeed shine a detailed light on the lives of lower middle-class men struggling to get ahead, but it was in company with contrasting insights into William Cooper’s surprising rise from his working-class origins. More important were their complex stories of class mobility and class relations in expatriate settings. Most surprising were intimate insights into a passionate expatriate marriage thanks to several years of letters, with implications for our understanding of middle-class marital sexuality and attitudes to birth control. Expatriate social mobility seemed never to be straightforward, with evidence of painful class tensions, when social and occupational elevation could bring with it resentment and anxiety. Edgar Wilson, at the height of his career, a general manager and company director, could still rage from Baghdad against his upper-class colleagues in London: ‘the other directors are very well-to-do & don’t care a dam (sic) what happens apparently, as long as they are making money, no matter how’.Footnote 34 Social mobility abroad came with its own complications.

This brief account of the archive does scant justice to my first encounter with it as I pored over the weighty bound volumes. Initially, my narrow focus on Edgar Wilson, his class background, career and first marriage directed me to his memoir, but that soon led on to his letters to his second wife, her family background, and the complex career of her father in the world of telegraphy. These lives of initially ‘ordinary’ people were exceptionally well recorded. Their stories transported me to the intriguing and varying worlds of Edwardian expatriates: the small Georgian multicultural outpost of ‘Sukhum Kaleh’ (now Sokhumi) on the Black Sea; a succession of isolated coastal stations on the Persian Gulf; close-knit European communities alongside the diplomats of Tehran; and the life of shipping agents in remote Persian Ahwaz on the Karun river, where Edgar Wilson encountered the early stages of oil exploration and he and his wife and daughters survived grave risks during the First World War. A large volume of photographs helped to enhance the written impressions of the intriguing and varying worlds of Edwardian expatriates, along with ephemera such as passports, employment contracts, accounts of stored household belongings and even Second World War air raid warden medals. When I met Isobel Howden for an interview at her home in Bury St Edmunds, she prepared a table with her mother’s wedding dress and presents, jewellery and more photographs. Gradually, a picture of the lives of these two expatriate families and their connections came into focus. My earlier research on the English lower middle class soon gave way to something between a social history of expatriate social mobility and a life history of the Coopers and Wilsons. To paraphrase Emma Rothschild’s summary of her Inner Life of Empires, this book is about a family’s outer lives, their travels, employment, conflicts, wills, births and deaths, but also about their inner lives, their responses to local and world affairs, their loving and intimacies, their spirituality and their joys and anxieties through war and peace.Footnote 35

The book begins logically with the early life and white-collar career struggles of Edgar Wilson (Chapter 1), followed by a chapter on William Cooper’s international telegraphy career (Chapter 2). These set the stage for Chapter 3, on the education and courtship of William’s daughter, Winifred Cooper, the eventual wife of Edgar, based largely on her own diary and correspondence. The heart of the book lies in Chapters 4 and 5, based overwhelmingly on Winifred’s diary and spousal correspondence, used to explore her marriage with Edgar and their lives during extended separations and periodic reunions in Iran, Iraq and England, from First World War struggles to the mid-1920s. Chapters 6 and 7 take us to the retirements and later lives of Edgar and Winifred, as well as William and his wife Alice, mostly ‘back home’ in England. Winifred created for herself a life with her two daughters and two stepsons in the town of St Albans, where she became a prominent community leader. The later lives of the two men in her life, Edgar and William, highlight their different attitudes to travel and to life after employment: William’s fateful travel enthusiasm in contrast to Edgar’s contentment with the suburban settlement he had achieved through his overseas labours.

The book draws together two unlikely thematic bedfellows: on one hand, the ‘big picture’ history of the business of empire, trade and communications, on the other, a social history of the private and inner worlds of family, domesticity, love, sexuality and religious attachment. The opportunities for social mobility in overseas business settings link the two. The worlds of Middle East shipping and telegraphy, of British activities in Tehran and Baghdad and of ‘Great Game’ political competition with Russia are seen here, uniquely, through the lens of Britons on the move, geographically and socially. Similarly, the expatriate experience offers novel insights into major themes of social history, such as class, marital relations, sexuality and gender. The lives of Edgar, Winifred, William and their contemporaries open a rare window into the process of expatriate social mobility, an experience which affected the lives of thousands of ordinary British men and women at the height of empire and after.