1.1 Overview

The fundamental institution of contemporary China is communist totalitarianism with Chinese characteristics. This institution differs fundamentally from non-communist totalitarian regimes, ancient Chinese systems. It also differs in many aspects from the Soviet Union. It originated in Soviet Russia and its deep roots in China are inseparable from the foundations of ancient Chinese institutions. How does this institution dictate the behavior of the contemporary Chinese government? How have China’s institutions and their basic features evolved to the shape that we observe today? In which direction will these institutions change in the future? Academic research in this area is generally weak and has many gaps. This book aims to strengthen academic research in this area and fill in those gaps. By doing so, I hope to establish a solid foundation for interpreting China’s historical and contemporary context, while offering insights that may assist in predicting potential future shifts. For those who care about China’s reforms, this provides the basis for recognizing where the country’s fundamental problems lie and for understanding how to reform its institutions.

In this book, totalitarianism refers to an extreme type of modern autocracy characterized by total control over society through a totalitarian party, which is categorically different from any political party (further explained in Chapter 8). A totalitarian party is a modern organization that applies modern methods of control and propaganda. The descriptive definition proposed by Friedrich and Brzezinski in Reference Friedrich and Brzezinski1956 is still a valid summary of the system. This definition identifies six fundamental, complementary components of the system: Ideology is at the core of the totalitarian party’s control of the populace; and the party monopolizes and relies on ideology, secret police, armed force, the media, and organizations (including businesses) throughout society and controls all resources through this channel (Friedrich and Brzezinski, Reference Friedrich and Brzezinski1956, p. 126).

The first totalitarian regime that fit the above definition emerged from the October Revolution in Russia in 1917. Since then, the world has seen totalitarian systems founded on various ideologies. However, the term “totalitarianism” was not coined until the 1920s. The value of a totalitarian ideology at the core of the system lies more in providing legitimacy, cohesion, and mobilization to the regime as a governing tool, rather than in its nominal expression, which has purposely been made misleading by the communists (see Chapters 8, 10, 11). In fact, its extreme autocratic nature determines that regardless of its nominal ideology, essential parts of its expressions will be grossly self-contradictory to the operation of that system. For example, for communist totalitarianism with a nominal ideology of Marxism, the fundamental ideology is the dictatorship of the proletariat and the party’s unquestionable ruling position (Leninism). These are not only the basic principles of the specific institutional arrangements of the totalitarian regime but also the basis of its legitimacy. However, the communist ideology of absolute egalitarianism and the Marxist ideology of human freedom with humanitarian connotations are in serious contradiction with the operation of the totalitarian system. Anyone who adheres to a given nominal ideology, yet disobeys the paramount leadership, will face severe punishment under the totalitarian system, regardless of their position. They may even face physical elimination, as was the case with figures like Bukharin and Trotsky of the Soviet Union and Liu Shaoqi and Zhao Ziyang of China, among others.

While the entry of communist totalitarianism into China was initiated and strongly supported by the Soviet Communist Party, it is indisputable that the establishment of a communist totalitarian system in China, at the cost of millions of lives, was a choice made by Chinese revolutionaries, not the Soviet Red Army. The question is, the end of the Chinese imperial system (dizhi 帝制)1 was brought about by a series of reforms and revolutions aimed at promoting constitutionalism,2 but why did China ultimately choose the opposite, totalitarianism? Moreover, a recent puzzle is why China is still stuck with totalitarianism after several decades of reform and opening-up and with private enterprise already dominating its economy.3 Why has the totalitarian system taken root in China so profoundly? A more fundamental and universal question is, why did human society give rise to a totalitarian system? Why did this system originate in Russia? What similarities exist between the institutional legacies of Russia and China? To answer these questions, this book proposes an analytical concept of institutional genes. “Institutional genes” in this book refer to those essential institutional components repeatedly present throughout history. In Chapter 2, we will discuss the definition and mechanisms of institutional genes in detail. Using this concept, we will analyze the emergence, evolution, and characteristics of contemporary China’s institutions from both a transnational and historical perspective. Additionally, we will explore the genesis of totalitarianism, particularly in Russia. The concept of institutional genes and its analytical framework are significantly inspired by institutional design (mechanism design) theory4 and the path-dependence theory of North in economics.

Between 1989 and 1992, totalitarian regimes in the Soviet Union and Central Eastern Europe collapsed. This series of historical events stimulated academic research on institutions and spurred significant developments in the field. Several scholars, such as North and Coase, received the Nobel Prize in Economics for their work related to institutions. Nonetheless, aside from Kornai’s work in 1992, most renowned political economy studies have not delved into the subject of totalitarianism, nor have they analyzed the transition from totalitarian to authoritarian regimes in those countries.5 This research gap in economics and political economics, in particular, has caused a lack of basic understanding of the regimes of China, the Soviet Union, and other former communist countries, making it difficult to anticipate or respond to political reversals in those countries. From an academic and policy perspective, this seems similar to the awkward situation economists faced in predicting and responding to the global financial crisis of 2008. However, the comprehensive consequences of a totalitarian superpower across the globe, from direct geopolitical, economic, and military impacts to the indirect influence on the institutions of other countries, far surpass the consequences of a financial crisis in terms of breadth and depth. The propositions discussed in this book, therefore, pertain to institutional evolution in general and are not limited to China, Russia, or countries experienced in totalitarian rule.

This book presents and develops the basic concept, or analytical framework, which I refer to as “institutional genes.” “Institutional genes” is a term I coined in this book. It refers to essential institutional elements that serve as the foundations for other institutional elements and often appear repeatedly in history. It is a methodological approach proposed for the in-depth analysis of major issues in institutional evolution. This book applies the institutional genes framework to organize historical evidence, using historical narratives to elucidate why the constitutional revolutions in Russia and China in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries faltered. It also examines the paradoxical outcome of these revolutions, which, rather than fostering constitutional principles, instead gave rise to totalitarian systems that contradicted them. Further, it sheds light on the crucial institutional changes that these two countries have undergone over the past century and their lasting influence not only on their own trajectories but also on the global political economy.

There are many conceptions of institutions. In this book, the discussion of institutions focuses on three fundamental elements: human rights, property rights, and political power. In connection with this focus, the Locke–Hayek thesis on the inseparability of human rights and property rights is reinterpreted in the context of the history and reality of totalitarianism (Chapters 2 and 3). The essence is that the property rights structure of any society is inseparable from the structure of political power in that society, as can be observed from the arguably most egalitarian distributional structure of Scandinavian regimes to the most unequal structures of communist regimes. Accordingly, the concept of property rights used in this book is based on the notion of ultimate control rights – a concept employed by Locke, Marx, Mises, Hayek, and Hart (residual rights, Hart, Reference Hart2017), and one that was widely accepted in academia and practice before the twentieth century. Chapter 3 explores the relationship and differences between this concept and the concept of a “bundle of rights” that has gained popularity since the twentieth century. Throughout the book, the origins of totalitarian systems are explored through historical narratives, emphasizing how the institutional genes of these regimes stemmed from a deep-rooted monopoly on property rights and power and the resulting social consensus that solidified these structures.

From the perspective of property rights and power structures, a totalitarian regime consolidates all property rights and power within society under the control of the totalitarian party, thereby subjecting all individuals’ human rights entirely to the party’s authority. In contrast, no dictator, government, party, or institution in any other autocratic system enjoys such comprehensive control over property rights and power. Furthermore, the nature of the totalitarian party dictates that it is not a political party in the conventional sense (as detailed in Chapter 8).

With the world currently facing the threat of the totalitarian power of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), it is particularly important to revisit Mises’ warning at the end of the Second World War – that the free world’s multi-decades’ efforts to contain totalitarianism have all failed. Unfortunately, this warning has long been completely forgotten. The neglect of totalitarianism in academic and policy circles has allowed the CCP to receive unchallenged assistance from the West across various domains, fueling its meteoric rise not only in economic strength but also in the expansion of its propaganda, police, and military capabilities. Even today, recognizing the totalitarian nature of the CCP remains a significant challenge in the West. Under such favorable conditions, the collapse of the Former Soviet Union and Eastern European (FSU-EE) totalitarian bloc was followed by the unfortunate expansion of the Chinese totalitarian regime into a threatening superpower – a development that could not have occurred without the support of the United States and other democratic nations. Existing academic discussions on totalitarianism, while still valid, are largely based on decades-old literature. These discussions have often been confined to philosophy, intellectual history, or the historical records of Soviet Russia, with few efforts made to systematically study the comprehensive and fundamental mechanisms of totalitarianism within the context of the century-long rise of communist totalitarian regimes. Addressing these gaps, Chapters 6 to 8 of this book explore the origins of totalitarianism as both an ideology and a system, the reasons it emerged first in Russia, and the mechanisms through which it rises and operates.

Totalitarian regimes are characterized by the complete eradication of private property and total control over society through extreme violence. Such regimes emerged from a secular political-religious movement known as the World Proletarian Revolution. This movement, driven by the pursuit of egalitarianism and a form of secular messianism, relied on so-called class struggle, which was both highly seductive and inflammatory, fueled by hatred towards the so-called class enemies. However, this secular religious movement only succeeded in societies that possessed specific institutional genes – a highly monopolized structure of property and political power, along with a corresponding social consensus (Chapter 6). The communist totalitarian movement was first established in Russia because it had the necessary institutional genes to create such a regime. These genes included the autocratic Tsarist regime, the pervasive influence of Russian Orthodoxy, and the well-developed network of sophisticated secret (terrorist) political organizations (Chapter 7).

The Bolshevik Party, the world’s first communist totalitarian party, originated as a secretive political organization. Chapter 8 discusses the creation of this party and its transformation into a full-fledged totalitarian party, including the development of its operating mechanisms. The role and mechanisms of the institutional genes that facilitated the formation of the Leninist party in establishing and consolidating a totalitarian regime are analyzed. The creation of the Soviet regime involved the suppression of opposition through the dictatorship of the proletariat, the establishment of a Red Terror regime, the creation of comprehensive state ownership, and the formation of the Comintern (Communist International), the organization that spearheaded global communist totalitarian revolutions. The CCP and other communist parties around the world were established with the support of the Comintern, with their founding principles and operational mechanisms transplanted from the Communist Party of Soviet Union (CPSU). To this day, all the CCP’s fundamental principles remain derived from the CPSU. Additionally, Chapter 8 systematically analyzes the basic nature and operational mechanisms of totalitarian parties and how these evolved from the institutional genes of Tsarist Russia. This analysis is essential for understanding the nature of totalitarian parties in general, making this chapter crucial even for readers primarily concerned with China.

Chapters 4, 5, and 9 analyze the origins and evolution of the institutional genes of the Chinese imperial system and the mechanisms by which these genes impeded the development of constitutionalism within it. Chapters 10–13 explore how communist totalitarianism was transplanted into China by the Comintern, how China’s institutional genes facilitated the establishment of this totalitarian system, and how a Soviet-style communist regime was formed. The chapters also delve into the evolution of communist totalitarianism with Chinese characteristics – regional administered totalitarianism – during the Great Leap Forward (GLF) and the Cultural Revolution (CR) in the Mao era, and how this system supported economic development and reforms during the post-Mao era, ultimately preserving CCP rule while leading China into the trap of totalitarianism. From these discussions, it becomes clear that the so-called “middle-income trap” phenomenon observed since the late 2010s is merely a manifestation of the totalitarian trap, inherent in the nature of totalitarianism itself.

The final chapter briefly discusses the institutional transformations of the FSU-EE totalitarian bloc and Taiwan through the lens of institutional genes and explores the implications of these transformations for China’s future. The key feature that distinguishes the Chinese system from the FSU-EE totalitarian regimes – Regional Administered Decentralized Totalitarianism (RADT) – was instrumental in enabling China’s private enterprises to flourish under communist rule during economic reforms, becoming the primary engine of China’s economic growth and thereby sustaining the Chinese Communist regime. However, the sweeping reversal since the late 2010s suggests that the CCP may not be able to fully escape the fate of the CPSU. The fundamental institutions of communist totalitarianism remain unreformable and economic reforms appear destined to fail (Chapters 13 and 14). Furthermore, the peaceful abandonment of totalitarianism by the FSU-EE communist parties was driven not only by economic stagnation but also by immense social pressure and a growing social consciousness regarding human rights and humanitarian values. These pressures and social consensus are deeply rooted in the institutional genes of the FSU-EE countries (Chapter 14). In comparison, China has a much weaker social awareness of human rights and humanitarianism. Additionally, under CCP rule, the military has long been involved in politics and the CCP has deliberately institutionalized the grooming of princelings as successors (Chapter 14). These factors suggest that even in the face of prolonged economic stagnation, it may be more difficult for the CCP leadership to peacefully renounce totalitarianism than it was for their FSU-EE counterparts.

The key to understanding Taiwan’s democratic transformation lies in recognizing the pre-existing differences in institutional genes between Taiwan and mainland China, as well as the fundamental differences between authoritarian Kuomintang (KMT) rule and totalitarian CCP rule in suppressing the institutional genes necessary for constitutional democracy (Chapter 14). First, the short-lived rule of the Chinese imperial system in Taiwan ended as early as the late nineteenth century, leaving only a shallow influence of Chinese imperial institutional genes on the island. During the Taisho democracy era under Japanese rule, Taiwan began to develop the institutional genes of constitutionalism, including local elections and the assembly of political parties. Furthermore, the Comintern never reached Taiwan and the KMT was not a totalitarian party. Under KMT authoritarian rule, the institutional genes of democratic constitutionalism were suppressed but not eradicated; in fact, some were able to survive and even grow, albeit with difficulty. During the authoritarian period, when the Republic of China (ROC) Constitution was partially implemented, these institutional genes saw significant development through local elections, the rapid expansion of private enterprises, and the spread of civil society. This led to a growing social movement towards constitutional democracy. Taiwan’s institutional transformation was achieved precisely because the KMT authoritarian rulers yielded to and responded to this tremendous social pressure.

1.2 Institutional Divergence

China, Russia, and Japan, at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, each endeavored to promote the establishment of constitutional government. Japan succeeded while China and Russia failed. Since then, there has been an ongoing institutional divergence between these three powers that has had a major impact on the world.6 Japan was the first non-Western country to establish a constitutional government and became the first developed nation outside of Europe and North America (a thorough discussion of Japanese institutional changes, including its period of militarism, is beyond the subject of this book). After decades of endeavors towards a constitutional monarchy and republic, which ended their imperial systems, Russia and China, respectively, created and transplanted totalitarian institutions that ran counter to constitutionalism.

Since the end of the nineteenth century, for the first time in 2,000 years of Chinese history, the reform advocates who tried to change the Chinese institution called the traditional Chinese institution the “imperial system” (dizhi). This tradition has continued to this day among Chinese intellectuals who are critical of the institutions of the Chinese Empire. This book continues this tradition. The closest term in political science to dizhi, the Chinese imperial system, is an absolute monarchy. However, the powers in the Chinese imperial system were much more concentrated, such that there was no boundary between sovereignty and property rights and no judicial institution separate from the executives (Chapters 3 and 4 will explain further). These make the Chinese imperial system categorially different from the absolute monarchy in Western Europe. The Tsarist imperial system is more similar to the Chinese system than it is to the Western European absolute monarchy (see Chapter 7).

The study of the Chinese imperial system is highly relevant to its economic position in the international arena. This book argues that the most important reason for China’s decline and the limitations imposed on its catching up is its great institutional divergence. A century and a half ago, China, or the “Great Qing Empire,” had the largest economy in the world. Its economy was bigger than the sum of the second and third largest economies at that time. However, since the mid nineteenth century, China had rapidly declined. Riots, revolutions, and civil and foreign wars persisted. Concurrently, two constitutional reforms faltered, leading to the collapse of the Qing Empire and the Republican Revolution. However, the Republican Revolution also soon faltered. As a result, China became one of the world’s poorest countries, mired in conflict.

In 1949, backed by the Soviet Union, the CCP established the People’s Republic of China (PRC). At this point, China’s per capita gross domestic product (GDP) was a mere twentieth of the United States’ (calculation based on Maddison [Reference Maddison2003]). The nation remained in severe poverty for the subsequent three decades under the new regime. It was not until the post-Mao reform that China experienced more than three decades of sustained rapid development and became the world’s second largest economy. In 2018, China’s nominal per capita GDP was nearly one-sixth that of the United States, or 30 percent of the US figure measured by purchasing power parity (IMF, 2019).

If China develops to follow a similar trajectory to those of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, its GDP per capita will reach half that of the United States within the next twenty to thirty years, by which time China’s total GDP will exceed that of the United States and the European Union (EU) combined. It would be the biggest challenge not only to the global economy but also to global science, technology, politics, and even the military, similar to the expectations or fears about the rapidly developing Soviet Union during the 1960s and 1970s, even though the per capita GDP in the USSR never exceeded one-third that of the United States (Maddison, Reference Maddison2003). However, China’s basic institutions differ significantly from those of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. So, will China’s development trajectory follow that of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, or that of the Former Soviet Union or even the Qing Empire? What will happen if China cannot even maintain stability? The answer hinges on China’s institutions and how they will change.

Why did China and Russia, despite initial strides towards constitutional governance mirroring Japan, eventually veer in the opposite direction? Why, after the infiltration of totalitarianism into China, did the painstaking efforts of China’s intellectuals towards constitutionalism partially dissipate and partially shift the momentum in favor of totalitarianism? Why did the imported totalitarianism find a deeper foothold in China compared to that in Russia, its birthplace? Addressing these questions is essential to understanding contemporary China’s institutions and to anticipating China’s future trajectories.

Initiated in 1868, the Meiji Restoration represented a significant departure in institutional evolution. It laid the foundation for constitutional governance in Japan. Despite the major twists and turns of militarism, the Meiji Restoration and the subsequent constitutional democratic reforms introduced during the Taisho period laid the foundation for the final establishment of a democratic system in Japan after the Second World War. Conversely, both Tsarist Russia and Imperial China, following their respective military defeats by Meiji Japan, embarked on a series of constitutional reforms and revolutions aimed at establishing constitutional monarchies and republics. These tumultuous changes led to the collapse of both empires. However, rather than establishing constitutional rule, they rebounded to form the world’s first and largest totalitarian regimes, respectively. And it was in China that the seeds of totalitarianism took the deepest root.

Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905 sparked a revolution that led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy and the State Duma, the legislative body. Despite holding several sessions between 1905 and 1917 after general elections, the constitutional monarchy remained unstable, which paved the way for the Bolshevik Revolution. The Russian efforts towards constitutionalism started in 1814, at the end of the war against Napoleon. During that year, members of the Russian military elite found themselves galvanized by the example of the French Revolution and the desire for constitutional government in Russia was first kindled. This inspiration spurred decades of tireless work by the revolutionary pioneers, culminating in the establishment of a constitutional monarchy after the 1905 revolution and a republican provisional government in 1917. Although the century-long struggle for constitutionalism was fraught with turbulence and hardship, and the Provisional Government was weak and faltering, it was not exceptional compared to the tortuous journey towards constitutionalism in most countries around the world. What made Russia profoundly influential in human history was the Bolshevik coup of 1917 (interpreted as largely a collection of coincidences by many historians), which completely ended a century of efforts towards constitutional government in Russia and created the world’s first totalitarian system. Why did Russia have such difficulty achieving constitutionalism, yet later shift so easily to its opposite, totalitarianism?

By the time Soviet totalitarianism permeated China, the conditions there largely mirrored those of revolutionary Russia. Following its defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1895, China twice attempted to enact constitutional reforms akin to those in Japan, yet both attempts foundered. The drive for institutional reform was eventually transformed into a revolutionary call and, subsequently, the revolutionary objective pivoted from republicanism to its opposite direction, communism. After enduring several brutal setbacks, a new generation of Chinese revolutionaries embraced Bolshevik missionaries, the Comintern. They willingly adopted Soviet institutions and constructed a totalitarian system, which stood in stark contrast to the constitutional framework that their predecessors had originally aimed to establish. I refer to this significant shift as the “Great Institutional Divergence.”

Since its inception in Russia in 1917, totalitarianism has spread globally at an unprecedented rate, outpacing the expansion of any other ideology or institutional model in human history. By the 1970s, the world’s population under totalitarian regimes surpassed the combined membership of all Christian denominations, the world’s largest religion. Moreover, without exception, all countries that voluntarily embraced totalitarianism had been autocratic states with no prior experience of constitutional government. It is evident that this phenomenon cannot be solely attributed to the ascent of a single leader or the triumph of an armed insurrection.

However, research into the patterns in the emergence and evolution of totalitarian systems remains sparse. Many scholars specializing in institutional studies, including those focusing on authoritarian regimes, tend to disregard the distinct characteristics of totalitarian systems, such as those found in China and the Soviet Union, and their influence on other nations’ institutions that goes beyond geopolitics. Many China specialists tend to underestimate the Soviet Union’s foundational role in shaping contemporary China’s institutions. Additionally, numerous Soviet experts often overlook totalitarianism’s origins and its continuing impact on today’s Russia and the world.

1.3 China’s Institutional Evolution

The downfall of the imperial system in China heralded the advent of totalitarianism. A century ago, pioneers of constitutional reform and the Republican Revolution perceived constitutionalism as an inescapable route towards China’s advancement. Despite distinct approaches, both the Hundred Days’ Reform (戊戌变法) and the Xinhai (辛亥) Revolution shared the common goal of instituting constitutionalism and substituting China’s imperial institutions with successful models from developed countries. But these attempted institutional reforms and republican revolutions all failed.

The key question to be analyzed and discussed in this book is why China had difficulty establishing a constitutional system originating from the West (including learning from Japan) but ended up rapidly and firmly establishing a totalitarian system originating from the Soviet Union in a relatively short period. What were the institutional antecedents in China for such a development? Subsequently, China transformed Soviet totalitarianism into regionally administered totalitarianism (RADT), totalitarianism with Chinese characteristics, through the Great Leap Forward and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.7 Having been deeply rooted in society, RADT formed the institutional foundation for China’s post-Mao reform and made the Chinese communist regime more adaptable and sustainable. What were the institutional origins of RADT? What is the relationship between RADT and the major challenges confronting China today?

There have been three dominant views on political reform in academic and policymaking circles about China’s more than forty years of reform. The first view holds that China’s national conditions or institutions are unique and that a democratic constitutional system is not suitable for China. The second holds that constitutional democracy is the ultimate objective of reform but a phase of neo-authoritarianism is needed as a transitional stage to develop the economy as a foundation for democracy.8 The third view rejects the above two perspectives and argues that China can, should, and indeed must implement reforms leading toward constitutional democracy.

China’s exceptionalism also often manifests in the form of the so-called “China model.” Does China’s uniqueness allow it to bypass the regularities universally observed by other nations? Can China’s economy sustain stable and continuous growth in the absence of constitutional democracy? These fundamental inquiries are what this book endeavors to tackle. Each of the three perspectives above relates to a series of basic social science questions: What are the main characteristics of China’s fundamental institutions? Why are these characteristics the way they are? How did they originate and evolve? Why did communist regimes emerge in Russia and China? Furthermore, what hurdles will China face as it transitions towards democracy?

Another prevalent view in academic and policy circles contends that economic development is an essential precursor to establishing constitutional democracy. This perspective argues that China requires a phase of neo-authoritarianism to address basic subsistence needs and foster a modern middle class before transitioning to constitutional democracy. However, as historical evidence abundantly demonstrates, in countries like Britain and the United States, the establishment of a constitutional democracy preceded an Industrial Revolution and economic development.

Philosopher Bertrand Russell concluded at the close of the Second World War that,

Ever since [Rousseau’s] time, those who considered themselves reformers have been divided into two groups, those who followed him and those who followed Locke. Sometimes they cooperated, and many individuals saw no incompatibility. But gradually the incompatibility has become increasingly evident. At the present time, Hitler is an outcome of Rousseau; Roosevelt and Churchill, of Locke.

John Locke was a trailblazer in modern constitutionalism and played a vital role in drafting the documents of England’s Glorious Revolution. His perspectives on human rights significantly influenced the US Constitution, the constitutions of all democracies, and the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. A century after Locke, French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau proposed that individual rights should be limited, or even nullified, for societal benefit and the so-called “general will.” He also maintained that private property rights are a source of inequality. Rousseau’s theory was put into practice during the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror led by the Jacobins and inspired Gracchus Babeuf, who created the first communist movement with the aim of seizing power and wealth through violence to achieve absolute equality under the rule of a clandestine organization. The concepts and movements of Rousseau and Babeuf were further developed by Marx and Lenin, laying the foundation for totalitarianism.

Locke’s philosophy was never popular among Chinese and Russian intellectuals. Instead, thinking derived from Rousseau and Babeuf, and later developed by Marx and Lenin, prevailed among Russian intelligentsia and Chinese revolutionaries. To understand the origins of totalitarianism, a critical question arises: Why did Russian intelligentsia and Chinese revolutionaries embrace the ideas of Rousseau, Marx, and Lenin while rejecting Locke’s?

1.4 The Institutional Regime in Contemporary China: An Outline

The nature of contemporary China’s fundamental institution is a subject of ongoing debate. In this book, I characterize it as Regionally Administered Totalitarianism (RADT), as previously mentioned, a concept that I expound upon in Chapters 12 and 13, along with an analysis of the regime’s evolution. Essentially, it began with the total Sovietization of China in the early 1950s.

The foundation of the classic model of totalitarianism that China adopted from the Soviet Union was the Chinese Communist Party, formerly known as China’s “Bolshevik” party. This entity initially received substantial support from the Soviets. The CCP’s authority was absolute, with the party maintaining comprehensive control over the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government, the armed forces, propaganda machinery and media, all resources, as well as all state and non-state organizations and enterprises. There was no separation between the party and the government. The party directly appointed all departmental officials and regional administration leaders at every level. Regional governments lacked autonomy, let alone sovereignty, and local party-state officials were appointed by their superiors within the CCP. In these aspects, China’s institutional regime mirrored the classic totalitarian model established in the Soviet Union.

In the RADT system, local party-state agencies are delegated with administrative and economic functions, as well as the bulk of resources, under the totalitarian premise of centralized appointment and political and ideological control. This institutional change from classic totalitarianism to RADT began in 1958 with the implementation of the Great Leap Forward and was solidified during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976).

RADT was the institutional foundation of the post-Mao reform. In the initial three decades of reform, with the aim of preserving the regime, the party’s societal control passively slackened as private businesses flourished in downstream manufacturing and the service industry. Simultaneously, a limited degree of pluralism began to take shape. The emergence of private property ownership, community organizations, and limited ideological diversity, along with expansion of the media, gradually diluted the party’s dominance in socioeconomic matters and ideological discourse. This period witnessed a partial transition towards authoritarianism, more specifically, regionally decentralized authoritarianism (RDA),9 albeit this shift was transitory in nature. Since the second decade of the twenty-first century, despite many of China’s elites eagerly anticipating reforms towards constitutionalism, China’s system has instead reverted to totalitarianism, that is to say, RADT. It is important to note, however, that history’s so-called repetitions only recreate certain fundamental features in new circumstances, not every detail. Today’s return of RADT in China is no exception.

Constitutionalism as an ideology made its way into China decades before the establishment of the first communist totalitarian regime in Russia. When the Russian Bolsheviks created the CCP, most of its founding members had a very limited understanding of communist ideology (as detailed in Chapter 10). But why did communist totalitarianism gain a foothold in China instead of constitutionalism? Why did totalitarianism not maintain its classic form in China, as it did in other communist countries, but rather evolved into RADT? Why has RADT become so deeply entrenched and difficult to remove in China? The answers to these questions can be found by examining the characteristics of China’s institutional genes and the necessary institutional genes that underpin totalitarianism.

The institutions of Imperial China represent the most enduring and meticulously organized autocratic systems in global history. The long-term stable structure of the Chinese imperial system is directly related to its unique institutional genes. Some of the basic components of these institutional genes originated in the Warring States period before the establishment of the empire. During the early phase of the unified empire under the Qin and Han dynasties (from 221 bce to 220 ce), imperial institutions began taking shape. In the long process of the collapse of the imperial system and subsequent reunification, the institutional genes of China’s imperial system were significantly improved during the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties (from 581 to 1279). In the following millennium, these improved institutional genes became highly stable. During the process of dynastic changes, they continuously replicated and evolved. After the Mongols and Manchus overthrew the Song and Ming dynasties, they abandoned their own ruling methods and adopted Han Chinese imperial institutions (see Chapters 4 and 5).

Institutional genes and the incentive-compatibility issue of the key players in institutional changes10 largely determined the fate of various reforms and revolutions in modern Chinese history. The half-century-long endeavor towards democracy and constitutionalism, from constitutional reform to the Republican Revolution, ended in failure. By contrast, the process of establishing totalitarianism in China was very rapid and firm. After the collapse of the Chinese Empire, some institutional genes from the imperial period continued to self-replicate in new forms within the totalitarian system until today (see Chapters 9–12). The crux of comprehension lies in recognizing the parallels between the institutional genes of China’s inherent imperial system and those of the imported totalitarian regime.

1.5 The Institutional Genes of Regionally Administered Totalitarianism

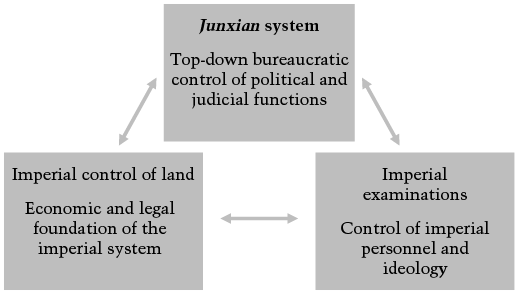

The governance structure under the RADT in contemporary China constitutes an institutional trinity: a tripartite blend of fundamental institutional elements that underpin China’s entire political and economic framework. Figure 1.1 delineates these institutional elements and their interconnections. The central box at the top represents the party-state bureaucracy, which lacks separation between executive and judicial functions. On the lower left, we see the party-state’s control over property rights and law, manifested in state ownership of all the land, a state-dominated financial sector, and a monopoly over the economy’s commanding heights. Lastly, on the lower right, we find the CCP’s control over official personnel and ideology. This power structure ensures the party’s absolute societal control, upholding stability by securing political, economic, and personnel support for the totalitarian system. Chapters 3–5 and 10–12 delve deeper into what makes this structure qualify as an institutional gene of contemporary China’s regime and they trace its evolution.

Figure 1.1 The power structure of regionally administered totalitarianism (RADT).

In the RADT regime, local governments hold complete administrative and economic functions under the premise that all local party officials are appointed from above and that political and personnel matters are highly centralized. The absence of specific centralized directives or planning instructions to localities in terms of specific administrative and economic management is a fundamental difference between RADT and classical totalitarianism. Figure 1.2 encapsulates the salient attributes of the central–local governance framework and power distribution under RADT. To underscore the decentralization of administrative and economic authority, Figure 1.2 only illustrates the functional arrangement at the central and county governance levels. Although similar configurations exist at intermediate levels, they are omitted for brevity. As shown in Figure 1.2, grassroots local party-state authorities possess nearly all the fundamental functions akin to those of the central authorities. Additionally, local party-state authorities take the lead in overseeing the comprehensive management of these functions. The section will delve into the pivotal role the RADT system played in China’s economic reform. More importantly, Chapters 4, 5, and 9–12 will analyze the genesis, evolution, and continuity of this system throughout China’s imperial period as well as during the CCP’s revolutionary and governing periods.

Figure 1.2 Institutional genes of the regional governance structure under RADT.

China’s distinct RADT system came into being via the partial deconstruction of Soviet-style institutions during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. Chapter 12 scrutinizes why, after the comprehensive transplantation of totalitarianism from the Soviet Union, China’s “continuous revolution” transformed into the RADT system.

1.5.1 Origins of the Institutional Genes of the RADT System

The institutions of contemporary China are inextricably linked to those of the former empire. To comprehend the genesis of the institutional genes underpinning China’s contemporary system (as depicted in Figures 1.1 and 1.2), we need to examine the institutional genes of China’s imperial system (Figures 1.3 and 1.4). A comparison of Figures 1.1 and 1.3 reveals striking resemblances between the institutional genes underpinning the power structures of both the imperial era and the present day. Subsequent chapters of this book will delve into the specific parallels between the institutional genes of ancient and modern China, the factors contributing to these similarities, and the mechanism facilitating their transmission.

Figure 1.3 The trinity of institutional genes comprising the governance structure of China’s imperial system.

Figure 1.4 Institutional genes of China’s junxian bureaucracy since the era of the Sui and Tang dynasties.

At the center part of imperial China’s trinity of institutional power, as depicted in Figure 1.3, was the bureaucratic system established under the Qin dynasty (221–206 bce), known as the junxian 郡县 (prefecture-county) system.11 The judiciary was always an intrinsic part of the bureaucracy. In this top-down bureaucracy, bureaucrats appointed by the emperor replaced the aristocrats’ rule over local areas during the Zhou dynasty. The judiciary was also inherently embedded within the bureaucracy. The primary threat to imperial authority was the potential rise of a new nobility from within the imperial system itself. Since the aristocracy that might arise within the imperial system was the greatest potential threat to challenge imperial power, the empire had to prevent that from happening whenever possible. The imperial land system,12 as shown in the lower left box in Figure 1.3, instituted since the Qin dynasty, served to eradicate the aristocracy.

However, the amalgamation of imperial land control and bureaucratic systems proved insufficient to prevent the emergence of a hereditary, de facto nobility, who often intended to be independent of the emperor. The imperial examination system, formally established during the Sui and Tang dynasties (with an earlier version introduced during the Han dynasty, though it was not fully institutionalized), as shown in the bottom right box of Figure 1.3, served as a critical personnel strategy that disrupted the intergenerational transmission of power among senior officials. It was an instrument of personnel control that safeguarded the emperor’s absolute authority over the bureaucracy. Simultaneously, it also served as a tool for ideological control, ensuring that all individuals entering the bureaucracy were properly indoctrinated with loyalty to the monarch. Upon the consolidation and refinement of this institutional trinity during the Song dynasty (960–1279), the emperor’s and the imperial court’s powers were effectively solidified. This robust institution of imperial rule remained unchallenged by any internally emerging powers for the subsequent millennium.

Establishing effective rule at the local level is a critical priority for any empire. Figure 1.4 illustrates the structure of local control within the Chinese imperial system, delineating the institutional genes of the junxian system. By juxtaposing Figures 1.2 and 1.4, the remarkable similarity between the junxian system and today’s RADT becomes readily apparent. Chapter 12 examines how China’s institutional genes have localized the foreign totalitarian institutional genes, which has led to the formation of China’s contemporary institutional genes.

Figure 1.4 depicts the core functions of the imperial court, which were divided among Six Ministries that were responsible respectively for personnel, finance, examinations and rites, the military, judiciary (mostly penal affairs), and public construction. Each was headed by a minister appointed by the imperial court. At the local level, the expansive empire was administrated by prefectural and county authorities, or by provincial, prefectural, and county authorities, each of whom was under officials directly appointed by the imperial court. Faced with the trade-off between ensuring absolute imperial rule and the effectiveness of that rule, along with the logistical limitations in terms of communication and transportation, the empire delegated all administrative functions to officials at varying levels of local governments while maintaining strict control over the officials themselves. Each level, from the imperial court to the county, housed offices for imperial personnel, finance, examinations and rites, the military, judiciary, and public construction. These offices mirrored the functions of the Six Ministries, with a magistrate overseeing these functions at the county level. The functional structures at intermediary levels followed the same pattern, although they are not depicted in the diagram.

The institutional genes depicted in Figures 1.1 to 1.4 evolved and were refined during 2,000 years of the empire, tenaciously self-replicating at the core of the imperial system. Whether it was a dynastic change due to a peasant uprising or a dynasty ruled by invading foreign powers, these institutional genes continued to be replicated. Even after the collapse of the imperial system, these institutional genes continued to dominate the path of China’s institutional evolution through the choices of reformers and revolutionary elites.

1.6 Institutional Genes: From the Imperial System to Communist Totalitarianism

Communist totalitarianism is not native to China; it is, in fact, an imported system. Those who oppose the adoption of constitutionalism and democracy in China assert that these are foreign institutions and thus they are unsuited for China, predicting their inevitable failure. However, totalitarianism is also foreign to China. Why, then, is it deemed “suitable for China”? Furthermore, why has totalitarianism rooted itself so deeply in Chinese society? These issues are addressed in Chapters 4, 5, and 9–12.

A prevailing explanation for the revolutions in twentieth-century China centers around the country’s profound nationalism. This explanation indeed captures some truth, as Chinese nationalism, whether overt or covert, played a pivotal role in the Republican Revolution and the May Fourth Movement, which laid the groundwork for the CCP. However, it is worth noting that Russia was the largest foreign occupier of Chinese territory by the end of the nineteenth century, a fact that was well known to the Chinese. Additionally, during the Russo-Japanese War, the Qing Empire supported Japan’s endeavors to expel Russian forces from China. If one applies the nationalism perspective literally, the Russian-inspired revolution should have faced strong opposition from nationalist revolutionaries during the post-May Fourth nationalist upsurge. Curiously, China’s radical revolutionaries, including prominent figures like Sun Yat-sen, Wang Jingwei, Liao Zhongkai, and influential participants in the May Fourth Movement like Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao, avidly embraced the Russian Bolsheviks’ revolutionary ideas immediately upon being exposed to them. Why? Regardless of the strategic choices made by individual revolutionary leaders, the revolutionary fervor of the participating, fervently nationalistic masses was not only a factor that these figures could seldom generate on their own but also one that could not be overlooked. This book delves into this inquiry by examining the institutional genes of the traditional Chinese imperial system and the totalitarian system through the lens of incentive-compatible institutional evolution.

The Hundred Days’ Reform of 1898, which aimed at establishing a constitutional monarchy, was the first attempt in China’s 2,000-year history to challenge the imperial system. Liang Qichao, a leading advocate of this reform, once said there had only been rebellions, not revolutions in Chinese history. By revolution, he meant replacing autocracy with constitutional government; by rebellion, he meant a change of dynasty that kept the same institutions in place. Any institutional change that curtails royal authority is inevitably incompatible with the interests of those in power. Thus, such successful changes necessitate the involvement of external forces beyond the monarchy’s control. Royal authorities would never willingly endorse a peaceful transition to constitutional monarchy without significant external pressure, which is strong enough and has its own power base. However, two millennia of imperial rule in China eradicated the nobility and other significant independent sources of power, and the remaining sectors of influence outside direct royal control were kept minor and feeble.13 The institutional genes of the imperial system, with its highly monopolized control over land rights, predetermined that a constitutional monarchy would be an institutionally incompatible change.

Indeed, the Hundred Days’ Reform and subsequent Late Qing Reforms were merely expedient attempts at self-preservation by the imperial court. According to the principle of incentive-compatibility, once the threat to survival was removed, the imperial authorities would employ every resource at their disposal to resist restrictions and undermine constitutionalism. Consequently, the incentive-incompatible institutional reforms introduced to China during this period all failed in succession. Eventually, many of the reformers who had initially supported a constitutional monarchy regarded the imperial court’s reforms as merely in name only, and they turned to support the revolution aimed at overthrowing the empire. The Republican Revolution of 1911 ended the longest-lasting imperial system in human history, but it failed to establish a stable constitutional alternative. The most devastating force to destabilize the Republic was Sun Yat-sen himself, the leader of the Republican Revolution. He initiated a “Second Revolution” and personally dismantled the fragile constitutional system that had just been established. Chapter 9 will delve into the pivotal role the imperial institutional genes played in many ostensibly random historical events.

A series of failed constitutional reforms and the Republican Revolution paved the way for the emergence of totalitarianism in China. Shortly after the Bolsheviks established a totalitarian regime in Russia, they created an international arm, the Comintern, which established a branch in China, the CCP. This marked the historical beginning of totalitarianism in China. When the Comintern was seeking to promote global revolution, China was considered a peripheral target. But the Comintern’s efforts in all of their main target countries ultimately failed. Although the transition to constitutionalism is rarely seamless anywhere in the world, it is exceptionally uncommon for a country to willingly choose and successfully implement totalitarianism. What made China special that the CCP, with the support of the Comintern, developed so rapidly, eventually seized power, implemented the Soviet system, and further established totalitarianism with Chinese characteristics? The answer to this historical anomaly, explored in subsequent chapters, lies in the close relationship between the institutional genes of totalitarianism and those of the Chinese Empire. On the other hand, the institutional genes of the Chinese imperial system and those necessary for a constitutional system are not only far apart but also are in conflict with each other.

1.6.1 The Genesis of Totalitarianism in Soviet Russia

Russian Bolshevism was the world’s inaugural totalitarian system. Despite Marx’s assertion that a proletarian revolution could only emerge in the most developed capitalist economies, not in a backward place like Russia or China, the Bolsheviks claimed to be Marxist and labeled their revolution as proletarian. Why then was Russia the birthplace of totalitarianism? This question is directly related to an understanding of the emergence of totalitarianism in China and the future of China. The explanation in this book focuses on how the institutional genes of Tsarist Russia contributed to the creation of the Soviet totalitarian system.

Some authors describe the establishment of Soviet power by the Bolsheviks as a collection of coincidental events or the emergence of Soviet totalitarianism in Russia as the result of conspiracy, cunning, and brutal violence. Each narrative reflects important aspects of history. However, such large-scale implementation of violence requires many people to execute it voluntarily, even creatively and fanatically. The incitement, fanaticism, organization, and brutality of the Bolsheviks required a highly intense incentive mechanism.14 So, history cannot be accounted for purely because of a gang of conspirators’ atrocities. These same traits characterized the strain of Bolshevism that later arose in China with the support of the Comintern. The tragedies of China’s Land Reform movement, Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries, Anti-Rightist Campaign, and Great Leap Forward, followed by the Cultural Revolution, all demonstrate the enthusiastic and active involvement of millions of zealous followers, guided and motivated by totalitarian leaders. The revolution spearheaded by the CCP generated incentives potent enough to unite the entire nation, despite Sun Yat-sen’s description of the Chinese people as being as disjointed as “a sheet of loose sand.” So, what incited this unity? The emotional resonance and organizational discipline of the party cannot be solely ascribed to coincidence. If it was not purely accidental, what was the underlying mechanism?

Chapters 7 and 8 analyze the emergence of three institutional genes in the Tsarist period which led to the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union: the secret political terrorist organizations of late Tsarist Russia, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the institutions of imperial rule under the tsars. From the outset, the Bolsheviks were markedly different from other Marxist parties in their organizational principles and methods, which were inherited from the secretive terrorist political organizations prevalent in Russian society. When Lenin founded the Bolshevik wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP) in 1903, its foundational principles closely mirrored those of the Narodnaya Volya, or People’s Will, a prominent political terrorist organization of that era. Lenin’s brother, who was executed following a botched assassination attempt on the Tsar, was a local leader of the Narodnaya Volya and several of the early Bolshevik leaders had strong connections with the organization. Even leading figures of the international communist movement at that time, such as Karl Kautsky and Rosa Luxembourg, criticized Lenin’s Bolsheviks as a terrorist organization and asserted that the Soviet regime would bring a reign of terror.15

However, the totalitarian party vastly outstripped the secret political terrorist organizations in capability. The biggest difference lies in its systematic, highly appealing ideology, extremely strong incitement, and extensive, religious-like ability of mobilization that permeated society. The roots of this extraordinary mobilizing capacity can be traced back over a thousand years through the history of Christianity and the Church (see Chapter 6).

In his later years, Engels wrote about the origins of communism and socialism in early Christianity (Engels, Reference Engels1895). Kautsky also explored the origins of communist thought in the Bible, pinpointing the medieval Reformation as the genesis of the earliest communist movements. Characterized by extreme zealotry and brutality, these movements – some carried out on a significant scale – were a characteristic feature of the Reformation in certain regions of Europe (Kautsky, Reference Kautsky1897, pp. 12–17). They were evident in several towns and cities across Central and Western Europe, and sometimes in established short-lived communist societies, such as the Hussites in Bohemia and the Münster Commune in Germany. Many other aspects of Marxist thought, including the idea of historical inevitability, the downfall of the old world and the rise of a new one, belief in a savior and redemption, and martyrdom, have their roots deeply embedded in Christianity (see Chapter 6). In many ways, the international communist movement led by Marx and Engels resembled a second Reformation but with historical inevitability, communism, Marxism, and Das Kapital replacing God, Heaven, Jesus, and the Bible. Chapter 6, based on historical evidence from Europe, explains the Christian origins of a secular religion, that is to say, communist totalitarianism. It also explains how this institutional gene made communist totalitarianism the most influential ideology and institution at one point. This is the intellectual starting point for understanding fanatic communist movements in Russia and China.

Just as the Roman Empire’s greatest contribution to Christianity was its establishment as the state religion, the Bolsheviks’ primary contribution to the communist movement was the creation of a secular totalitarian caesaropapism founded on Marxist ideology. Regarding ideology and mobilization, the institutional genes for totalitarianism in Russia originated from the branch of Christianity dominant in Tsarist Russia: Russian Orthodoxy, which had permeated the population of the land long before the existence of the Russian Empire. Whether by design or inadvertently, the Bolsheviks appropriated the Orthodox Church’s well-established mechanisms of propaganda, organization, and punishment to mobilize, appeal to, and govern for centuries. Through these inherited characteristics of the Orthodox Church, the Bolsheviks infiltrated and exerted control over Russian society, from ideology to organization and power structures. While it may be coincidental that Stalin received a formal education at an Orthodox seminary, the Bolsheviks’ successful emulation of the Orthodox Church was more than mere happenstance. In this political religion,16 Marxism-Leninism’s classics supplanted the Bible, revolutionary martyrs displaced Christian martyrs, and communist society emerged as the new heaven. Mirroring the methods of the apostles in disseminating the news of Jesus Christ, the Bolsheviks established a cult of personality around their leader, elevating him to the status of a saint and savior. Revolutionary heroes and martyrs were canonized, their exploits commemorated, and temples erected in their honor. The religious custom of mass rituals was replicated, while penance to God was transformed into penance to the party. Liu Shaoqi coined the corresponding phrase “criticism and self-criticism” for use in China, a country devoid of a comparable religious tradition, in his 1939 book How to Be a Good Communist. Under Stalin’s regime in the Soviet Union, classic Marxist works served as the Old Testament, while Stalin’s History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): Short Course (Stalin, Reference Stalin1975), supplemented by Lenin’s work on Bolshevism, constituted the New Testament. Mao Zedong adopted this blueprint, converting volumes of rehashed history into China’s uncontested “classics” and presenting himself as the “Great Savior of the Chinese People.”

Upon seizing power, the Bolsheviks soon dominated every facet of Russian society by controlling the government and all resources. The institutional genes for totalitarianism, in terms of practical control, originated from the Tsarist Empire. These include the Tsar and his court’s monopoly over political, economic, military, and judicial powers, the highly monopolized power structure of the system, control over the Church, and the social consensus (legitimacy) supporting the monopolization of power through violence. On this basis, the Bolsheviks developed a totalitarian system with a total monopoly of power and property rights that was unprecedented in human history, controlling all aspects of society wholly and comprehensively.

Marxist theory, echoing the Christian theme of salvation, posits that the international communist revolution can only triumph once everyone in the world achieves liberation.

1.6.2 The Rise of Communist Totalitarianism in China

The Comintern sent representatives to China soon after its creation but its delegates discovered that China was 500 years behind the advanced economies. According to Marxism-Leninism, such backwardness could only be peripheral to the Comintern’s operations. Yet, paradoxically, China emerged as the Comintern’s most significant success, if not its only success. As elucidated in Chapters 8–10, China’s institutional genes bore a striking resemblance to those that engendered Bolshevism, whereas they were distinctively different from those in the West. Of the three institutional genes that gave rise to Soviet totalitarianism, two similar ones were present in China: the imperial system and a tradition of secret societies. The monopolization of power, stringent controls, and the overall institutional stability of China’s imperial system were more pronounced than those of Tsarist Russia. Furthermore, China’s secret societies, such as the White Lotus Sect, the Green Gang, the Heaven and Earth Society, the Triads, and the Brotherhood Society, had a more extended history and were potentially more organizationally sophisticated than their Russian counterparts. This shared lineage of institutional genes facilitated the creation of a Bolshevik system in China and the launch of incentive-compatible communist totalitarian movements there.

However, one institutional gene that was crucial in the genesis of totalitarianism was absent in China: an Eastern Orthodox tradition. The emperors had curtailed the influx of Christianity and other Western ideologies into China. There was no widespread belief or consensus regarding a monotheistic God, God’s Truth, or a Savior, nor did any Church hold a national authoritative position. This absence limited the potential for generating totalitarian ideas in the vein of Marxism and Leninism and made it challenging to manifest such an ideology in the form of totalitarian institutions capable of penetrating and controlling society. Therefore, creating a totalitarian system in China necessitated direct involvement from an external force, such as the Comintern, to cultivate and support various aspects, including promoting beliefs, unifying thoughts, launching propaganda, and establishing organizations.

The largest insurrection in China’s late imperial period, the Taiping Rebellion, which spanned from 1850 to 1864, borrowed elements of Christianity. Certain Christian tenets were utilized to legitimize the uprising and proved highly effective in mobilizing the masses. However, Western missionaries and Western powers refused to support the Rebellion when they discerned that it was Christian only in name. In subsequent years, both Sun Yat-sen and Mao Zedong took Hong Xiuquan, the Rebellion’s leader, as a role model. Unlike the Taiping Rebellion, the Comintern directly introduced a new ideology into China, erected novel institutions, and actively endeavored to modify China’s institutional genes. As Mao Zedong declared, “The salvoes of the October Revolution brought us Marxism-Leninism.”

In 1920, the Comintern dispatched representatives to establish its branch in China. From the official establishment of the CCP in 1921 until the Comintern’s dissolution in 1943, the CCP functioned as a branch of the Comintern and identified itself as Bolshevik. All major decisions of the CCP had to be approved by the Comintern, which provided financial and material resources and selected the party’s top leaders. In 1931, under the Comintern’s guidance, the CCP founded the Chinese Soviet Republic, China’s first rudimentary totalitarian regime. From 1931, when Mao Zedong joined the CCP leadership, to 1938, when he ascended to the party’s highest-ranking leadership, he leaned heavily on the Comintern for recognition, direct support, and supervision. The party’s Yan’an Rectification Campaign in 1942 was a Stalinist purge with Chinese characteristics, after which Mao Zedong was elevated as the unchallenged leader who had full control over the CCP. From then on, the CCP became an independent Bolshevik party with a blend of institutional genes from both Imperial China and the Soviet Union, hence constituting a new and unique Chinese institutional gene.

After the Second World War, the CCP, with assistance from the Soviet Union, emerged victorious from the Chinese Civil War and subsequently established total control over China. From 1949 onwards, with the party serving as the linchpin of the regime, Soviet totalitarianism was comprehensively transplanted into China, encompassing diverse domains such as the economy, politics, law, military, education, and scientific research, among others. Even the inaugural constitution of the PRC was formulated under pressure from Stalin and with the assistance of Soviet experts; Stalin personally reviewed the final draft.

In places where totalitarian systems have developed, they often demonstrate significant strength in their early stages. Totalitarian parties employ methods such as incitement, violence, and coercion to generate extraordinarily potent incentives that result in the formation of the “masses.” These masses are manipulated into becoming formidable forces that dismantle the “old world” and construct a “new world” that paradoxically subjugates them in the end. Consequently, totalitarian parties seem to possess the capacity to establish systems that fundamentally contradict the incentives of the majority of individuals in society.

Unlike the establishment of totalitarian regimes, stable and long-term incentive-compatible systems that have emerged in human history have evolved slowly. This evolution is the process of synthesizing a large number of competitive, seemingly random short-term changes or events. In such an institutional evolutionary process, leaders and participants on all sides of the competition are mostly focused on short-term, local goals. For a conventional political party, including the early Social-Democratic parties within the communist movement, long-term objectives that were not incentive-compatible were unfeasible due to their lack of appeal for electoral support.

But a totalitarian party is an ideologically dominated, tightly controlled organization with iron discipline (internal factions are banned). The tight top-down organization and iron discipline of these parties enable them to promote highly seductive and inflammatory ideologies that conceal the truth and achieve their ultimate goal of eliminating competitors and gaining total control over society through a step-by-step plan. Ideology provides legitimacy for their totalitarian goals and step-by-step implementation is their strategy. Chapters 8 and 10–13 use historical evidence to analyze how the Bolsheviks and CCP decomposed their incentive-incompatible grand goals into multiple, often contradictory, short-term incentive-compatible goals, which were systematically and violently achieved through a divide-and-conquer approach.

Violence is an inherent component of totalitarianism. However, the resources available for violence are intimately tied to the totalitarian regime’s mobilization capacity. The violent upheaval of revolution, through which totalitarian systems are forged and refined, relies upon the mass mobilization of a substantial societal elite and working class, rallying them to the revolutionary cause.17 In China, the CCP effectively garnered mass support by leveraging China’s institutional genes to transform interim objectives into revolutionary acts or campaigns that aligned with the short-term incentives of a large populace. For example, it promised democratic freedoms to the elite and made commitments to secure land and property rights for the poor rural population. However, the CCP reneged on all of these promises, backed by coercive forces, within just a few years (see Chapter 11). Furthermore, these CCP actions were like a repetition to those of the Bolsheviks (see Chapter 8).

By strategically designing a mechanism for continuous revolution, inherently incentive-incompatible objectives can be decomposed into a series of short-term, seemingly incentive-compatible stages. This was the approach adopted by the Bolsheviks and the CCP extended this strategy to its extreme, with each stage of the revolution meticulously pre-planned. Ideology, proclaimed as “theory” by the party, provided a semblance of legitimacy for frequently self-contradictory initiatives such as the Land Reform movement and agricultural collectivization. In some instances, campaigns that served the established and long-term objectives were launched in response to specific events. One such instance was the Anti-Rightist Campaign, which was initiated in response to the “episodes” of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and Khrushchev’s secret speech to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Crucially, each short-term, incentive-compatible step in the process weakened or eradicated a segment of the political or social forces resisting revolution, including those within the party itself, thereby nudging the party closer to its incentive-incompatible totalitarian objectives.

The overwhelming majority of individuals, including many within the ranks of the CCP elite and leadership circles, would likely not have opted for totalitarianism had they been aware of its true characteristics in advance. With each stride towards complete totalitarianism, the system’s long-term incentive-incompatibility became more apparent to a greater number of people. The reason why a totalitarian system can still be established and solidified under such conditions is that the elimination of resistance and the establishment of totalitarian tyranny are advanced in a phased strategy. Every step along this trajectory involves the deployment of totalitarian organizations and collectives against individuals. At each stage, the party designs revolutions or movements that align with the short-term incentives to mobilize as many people as possible, aiming to gradually suppress or even eliminate dissenting individuals or groups in a piecemeal manner. At every juncture, the party harnesses sufficiently potent resources, reinforced by violence, to suppress or eradicate the targets of revolution specific to that stage. Individuals, recognizing their insignificance and helplessness in the face of this violent system, either surrender or even participate in the purging of others, thus becoming complicit in perpetuating the system. As this process repeats, the system amasses enough power to suppress any dissent towards the leader. Faced with a choice between obedience or purges under the threat of severe penalties, people generally opt for obedience, even if it entails participating in the purging of others. This forms the equilibrium of the totalitarian system under the tyrannical incentive-compatibility condition.

Although China’s imperial system was, arguably, the most centralized imperial system in human history, the modern totalitarian system is still far more centralized. In a totalitarian system, all means of production are owned by the state. The party, organized and controlled from the top down, uses ideology, personnel, and the armed forces as the basic means to take complete control of the government, the nation’s politics, economy, judiciary, ideology, armed forces, and every corner of society. In terms of the economy, along with thousands of Soviet experts and numerous Soviet-assisted development projects in the 1950s, the comprehensive operation of a Soviet-style totalitarian system also entered China. In this central planning system, the central ministries ruled the entire economy from the top down, a system that Mao described as a “vertically aligned dictatorship” (tiaotiao zhuanzheng 条条专政).

1.6.3 Institutional Genes: Regionally Administered Totalitarianism

While the personal role of Mao was important in transforming the totalitarian system in China from a classical one to one with Chinese characteristics, a much more important factor was China’s institutional genes. The most direct part of that was the local power pattern in the liberated areas before the CCP seized national power. And that in itself was a sort of extension of the institutional genes of the imperial junxian system. Before the CCP fully controlled China, the liberated areas were governed similarly to the imperial junxian system. Political and personnel matters were highly centralized, yet the regions maintained substantial self-rule in the administrative and economic spheres. The process of establishing a totalitarian system was a process of transforming China’s institutional genes with external totalitarian institutional genes. However, the “vertically aligned dictatorship” model of Soviet-style totalitarianism, introduced wholesale into China in 1950, proved to be significantly incentive-incompatible with the local power base of the CCP. Both the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, launched in 1958 and 1966, respectively, were attempts to discard this Soviet model and forge a totalitarian system that delegated more authority to regional administrations. Given that the transition towards RADT involved the reinvigoration of the imperial institutional genes inherited from the imperial era, there was a certain degree of truth to Mao’s self-proclamation in 1958 as a blend of Karl Marx and Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China.

The launch of the Great Leap Forward as a round of institutional changes first and foremost enhanced the paramount leader’s political powers, while simultaneously undermining or eliminating the already weak checks and balances that existed within the party and government. The powers of the central ministries were drastically curtailed and swathes of executive functions and resources were delegated to local governments. Newly empowered local governments were motivated to compete in loyalty to the leader, with regional competition supplanting central planning. Local governments were encouraged to experiment with new systems and strategies to expedite development towards communist totalitarianism (officially referred to as the transition to communism). Official propaganda declared that China should endeavor to be the first within the international communist movement to enter communism. The People’s Commune system was an invention of local governments during experimentation, while local competition was the mechanism for the rapid promotion of this system nationwide. In the process of dismantling Soviet-style totalitarianism and instituting RADT, however, the Great Leap Forward and the People’s Commune movement devastated the economy and sparked a famine on an unprecedented scale.

The Cultural Revolution, inaugurated in 1966 and spanning a decade, marked Mao’s second major attempt to advance the RADT system. Facilitated by a system that encouraged regional experimentation, the CR ignited a surge of Red Guards, Revolutionary Rebels, and Power-Seizing Movements nationwide. These forces, driven by personality cults and fueled by the mandate for perpetual revolution, wrought profound changes to China’s political landscape. Officials deemed inadequately loyal were brought down. All powers related to politics, personnel management, and ideology were concentrated in the hands of Mao and his associates. Central ministries and commissions were largely incapacitated and several were permanently dismantled. The administrative and economic responsibilities of the central government devolved almost completely to local authorities on a scale even surpassing that observed during the Great Leap Forward. By the early 1970s, China had morphed into an RADT economy characterized by multiple self-sustaining economies at various levels. The provinces and municipalities primarily functioned through self-sufficiency. The central party-state authority had to rely on local entities to implement its directives, thus transforming the so-called central planning into a task of coordination among local economies. Mao called this a “horizontally coordinated dictatorship” (kuaikuai zhuanzheng 块块专政).