Book contents

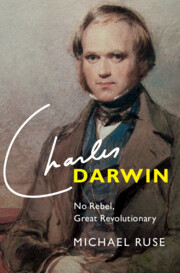

- Charles Darwin

- Frontispiece

- Charles Darwin

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Beginnings

- 2 Charles Robert Darwin

- 3 The Origin of Species

- 4 Evolution in the Nineteenth Century

- 5 Evolution in the Twentieth Century

- 6 Normal Science

- 7 Philosophy

- 8 Religion

- 9 Literature

- 10 Social Issues

- Epilogue

- References

- Index

1 - Beginnings

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 December 2024

- Charles Darwin

- Frontispiece

- Charles Darwin

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Beginnings

- 2 Charles Robert Darwin

- 3 The Origin of Species

- 4 Evolution in the Nineteenth Century

- 5 Evolution in the Twentieth Century

- 6 Normal Science

- 7 Philosophy

- 8 Religion

- 9 Literature

- 10 Social Issues

- Epilogue

- References

- Index

Summary

Since the Greeks, our world has been understood in terms of one of two root metaphors – the world as an organism (“organicism”) and the world as a machine (“mechanism”). With the coming of evolutionary ideas in the eighteenth century, we see that there are interpretations in terms of both metaphors.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Charles DarwinNo Rebel, Great Revolutionary, pp. 4 - 19Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2024