Refine search

Actions for selected content:

9 results

Chapter 12 - The Vision of Judgment and the Visions of ‘Author’

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Byron

- Published online:

- 02 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 16 November 2023, pp 193-208

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 36 - Monarchy, Royalty, and Arts Patronage

- from Part V - British Sociocultural, Religious, and Political Life

-

-

- Book:

- Benjamin Britten in Context

- Published online:

- 31 March 2022

- Print publication:

- 21 April 2022, pp 319-326

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Francesco Petrarch, Poet beyond the City

-

- Book:

- The City of Poetry

- Published online:

- 03 December 2020

- Print publication:

- 17 December 2020, pp 112-155

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Dante Alighieri, Poet without a City

-

- Book:

- The City of Poetry

- Published online:

- 03 December 2020

- Print publication:

- 17 December 2020, pp 63-111

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The City of Poetry

- Published online:

- 03 December 2020

- Print publication:

- 17 December 2020, pp 1-21

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Albertino Mussato, Poet of the City

-

- Book:

- The City of Poetry

- Published online:

- 03 December 2020

- Print publication:

- 17 December 2020, pp 22-62

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

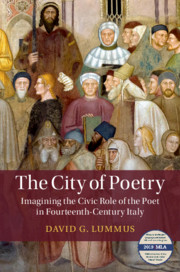

The City of Poetry

- Imagining the Civic Role of the Poet in Fourteenth-Century Italy

-

- Published online:

- 03 December 2020

- Print publication:

- 17 December 2020

Part VI - Chaucer Traditions

-

- Book:

- Geoffrey Chaucer in Context

- Published online:

- 24 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 11 July 2019, pp 401-444

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 48 - The First Chaucerians

- from Part VI - Chaucer Traditions

-

-

- Book:

- Geoffrey Chaucer in Context

- Published online:

- 24 June 2019

- Print publication:

- 11 July 2019, pp 403-409

-

- Chapter

- Export citation