Refine search

Actions for selected content:

58 results

Chapter 4 - “All the Logic I think Proper to Employ”

-

-

- Book:

- Hume's <i>A Treatise of Human Nature</i>

- Published online:

- 05 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 64-78

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

-

- Book:

- Hume's <i>A Treatise of Human Nature</i>

- Published online:

- 05 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 1-10

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - Hume’s Geography of Feeling in A Treatise of Human Nature

-

-

- Book:

- Hume's <i>A Treatise of Human Nature</i>

- Published online:

- 05 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 170-190

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - How to Read Book 2 of the Treatise

-

-

- Book:

- Hume's <i>A Treatise of Human Nature</i>

- Published online:

- 05 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 134-151

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Experimental Philosophy, Blind Submission, and Hume’s Other “Sceptical Principles”

-

-

- Book:

- Hume's <i>A Treatise of Human Nature</i>

- Published online:

- 05 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 116-133

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature

- A Critical Guide

-

- Published online:

- 05 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026

3 - Possession and Enslavement through the Holy Spirit

-

- Book:

- God, Slavery, and Early Christianity

- Published online:

- 19 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 October 2025, pp 131-165

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- The Law and Politics of International Legitimacy

- Published online:

- 14 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 24 July 2025, pp 488-491

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Ascetic Experience

-

- Book:

- Ways of Living Religion

- Published online:

- 07 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 March 2024, pp 14-55

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique

-

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023

4 - First Movement

-

- Book:

- Berlioz: <i>Symphonie Fantastique</i>

- Published online:

- 30 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 48-63

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

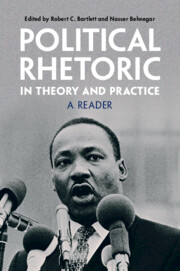

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Political Rhetoric in Theory and Practice

- Published online:

- 02 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 16 November 2023, pp 1-8

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The Modes of Persuasion: Ethos, Pathos, Logos (Character, Passion, Argument)

- from Part I - What is Rhetoric?

-

- Book:

- Political Rhetoric in Theory and Practice

- Published online:

- 02 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 16 November 2023, pp 103-143

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Political Rhetoric in Theory and Practice

- A Reader

-

- Published online:

- 02 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 16 November 2023

28 - Evagrius of Pontus on Λύπη: Distress and Cognition between Philosophy, Medicine, and Monasticism

-

-

- Book:

- The Intellectual World of Late Antique Christianity

- Published online:

- 05 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 530-547

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - “The tears stand in my eyes”

- from Part I - Johnson’s Criticism and the Forms of Feeling

-

- Book:

- The Literary Criticism of Samuel Johnson

- Published online:

- 07 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 September 2023, pp 34-52

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - In the Spirit of Plato

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Plutarch

- Published online:

- 29 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 13 July 2023, pp 79-100

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Hume and Smith

-

- Book:

- Modern Moral Philosophy

- Published online:

- 10 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp 201-236

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Coda

-

- Book:

- Sympathy in Early Modern Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 27 April 2023

- Print publication:

- 13 April 2023, pp 253-266

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Sympathy in Early Modern Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 27 April 2023

- Print publication:

- 13 April 2023, pp 1-34

-

- Chapter

- Export citation