Refine search

Actions for selected content:

82 results

Embedded Glottograms in the Images of the Gods in Ancient Central Mexico

-

- Journal:

- Ancient Mesoamerica , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 October 2025, pp. 1-22

-

- Article

- Export citation

18 - Glass

- from Part II - Artefacts and Evidence

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Late Antique Art and Archaeology

- Published online:

- 04 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 July 2025, pp 349-359

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

16 - Wall Painting

- from Part II - Artefacts and Evidence

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Late Antique Art and Archaeology

- Published online:

- 04 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 July 2025, pp 300-319

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

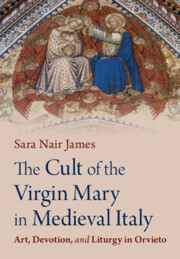

The Cult of the Virgin Mary in Medieval Italy

- Art, Devotion, and Liturgy in Orvieto

-

- Published online:

- 24 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 24 July 2025

Los cautivos tempranos de Oxpemul: Nuevas interpretaciones

-

- Journal:

- Latin American Antiquity / Volume 36 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 26 February 2025, pp. 222-238

- Print publication:

- March 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Forging Literary Connections

- from Part I - Protest

-

- Book:

- Vivisection and Late-Victorian Literary Culture

- Published online:

- 30 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 February 2025, pp 23-48

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Visualizing Christ's Miracles in Late Byzantium

- Art, Theology, and Court Culture

-

- Published online:

- 09 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 June 2024

Chapter 7 - Le Corbusier’s Impassive Partition Monument

-

- Book:

- Modernism and the Idea of India

- Published online:

- 02 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2025, pp 159-180

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Making Children Subjects of Empire

- from Part II - Themes in the Making of Hegemony

-

- Book:

- Religion and the Making of Roman Africa

- Published online:

- 24 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 November 2024, pp 229-269

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

HERCULES SLAYING CACUS IN THE HYPOGEUM OF THE VIA DINO COMPAGNI, ROME

-

- Journal:

- Greece & Rome / Volume 71 / Issue 2 / October 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 October 2024, pp. 264-286

- Print publication:

- October 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

3 - Christ’s Miracles

-

- Book:

- Visualizing Christ's Miracles in Late Byzantium

- Published online:

- 09 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 June 2024, pp 47-144

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 11 - Golden Locks Among the Greeks, or the Hair Secrets of the Beautiful Apollo

-

-

- Book:

- The Names of the Gods in Ancient Mediterranean Religions

- Published online:

- 23 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 March 2024, pp 207-230

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - The Sword and the Patera

-

-

- Book:

- The Names of the Gods in Ancient Mediterranean Religions

- Published online:

- 23 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 March 2024, pp 129-156

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Drunken Mountains: Analysis of the Bennett and Ponce Monoliths of Tiwanaku (AD 500–1100) from a Multispecies Perspective

-

- Journal:

- Latin American Antiquity / Volume 36 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 February 2024, pp. 181-201

- Print publication:

- March 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - The Magic Flute in 1791

- from Part I - Conception and Context

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to <i>The Magic Flute</i>

- Published online:

- 24 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 02 November 2023, pp 61-82

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

28 - Appealing to the Imagination

- from Part V - The Imagined Order of the Constitution

-

- Book:

- The Story of Constitutions

- Published online:

- 19 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 02 November 2023, pp 322-339

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

17 - Dissemination of Biblical Narratives, Motifs, and Figures through Early Christian Inscriptions and Homilies

-

-

- Book:

- The Intellectual World of Late Antique Christianity

- Published online:

- 05 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 303-327

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Maiores di pietra. L'immagine della famiglia nei monumenti sepolcrali della Regio X

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Roman Archaeology / Volume 36 / Issue 2 / December 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 October 2023, pp. 300-331

- Print publication:

- December 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

COMMEMORATING CANTILUPE: THE ICONOGRAPHY OF ENGLAND’S SECOND ST THOMAS

-

- Journal:

- The Antiquaries Journal / Volume 103 / October 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 October 2023, pp. 292-314

- Print publication:

- October 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation