Refine search

Actions for selected content:

14 results

Chapter 19 - Romanticism and the Sublime

- from Part III - In the Name of Time

-

-

- Book:

- Michael Field in Context

- Published online:

- 03 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 25 September 2025, pp 172-180

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - “How Can You Talk with a Person If They Always Say the Same Thing?”

- from Part I - Species, Lyric, and Onomatopoeia

-

- Book:

- Biopolitics and Animal Species in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Science

- Published online:

- 11 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 01 February 2024, pp 24-45

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 23 - Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967) and Edmund Blunden (1896–1974)

- from Part III - Poets

-

-

- Book:

- A History of World War One Poetry

- Published online:

- 18 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 12 January 2023, pp 379-391

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Ecphrastic Questions: Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Michael Field

-

- Book:

- Conversing in Verse

- Published online:

- 21 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 110-135

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Dialogue and the Idyll: Tennyson and Landor

-

- Book:

- Conversing in Verse

- Published online:

- 21 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 22-54

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 11 - Byron, Keats and the Time of Romanticism

- from Part II - Contemporaries

-

-

- Book:

- Byron Among the English Poets

- Published online:

- 22 July 2021

- Print publication:

- 29 July 2021, pp 188-202

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Physic and Metaphysics

- from Part II - Professionalisation

-

-

- Book:

- Literature and Medicine

- Published online:

- 04 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 24 June 2021, pp 97-118

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Only Connect

- from Part II - Psyche and Soma

-

-

- Book:

- Literature and Medicine

- Published online:

- 03 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 24 June 2021, pp 161-186

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

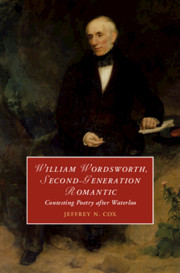

William Wordsworth, Second-Generation Romantic

- Contesting Poetry after Waterloo

-

- Published online:

- 10 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 20 May 2021

Chapter 5 - Late “Late Wordsworth”

-

- Book:

- William Wordsworth, Second-Generation Romantic

- Published online:

- 10 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 20 May 2021, pp 157-199

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - “This Potter-Don-Juan”

-

- Book:

- William Wordsworth, Second-Generation Romantic

- Published online:

- 10 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 20 May 2021, pp 110-128

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- William Wordsworth, Second-Generation Romantic

- Published online:

- 10 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 20 May 2021, pp 1-33

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - As With Your Shadow I With These Did Play, 1817–1900

-

- Book:

- The Afterlife of Shakespeare's Sonnets

- Published online:

- 16 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 29 August 2019, pp 135-190

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 15 - Plath and Art

- from Part III - Cultural Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- Sylvia Plath in Context

- Published online:

- 03 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 22 August 2019, pp 157-166

-

- Chapter

- Export citation