Refine search

Actions for selected content:

56 results

Chapter 26 - Intentional Objects in Later Neoplatonism

- from Part V - Metaphysics

-

- Book:

- The Ladder of the Sciences in Late Antique Platonism

- Published online:

- 08 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 350-359

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Imagining Antifascism

-

-

- Book:

- Antifascism(s) in Latin America and the Caribbean

- Published online:

- 21 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 August 2025, pp 184-207

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Igneous Rocks

-

- Book:

- Atlas of Minerals and Igneous and Metamorphic Rocks in Thin-Section

- Published online:

- 05 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 May 2025, pp 157-292

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Metamorphic Rocks

-

- Book:

- Atlas of Minerals and Igneous and Metamorphic Rocks in Thin-Section

- Published online:

- 05 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 29 May 2025, pp 293-390

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - In Praise of the City

-

- Book:

- The Idea of the City in Late Antiquity

- Published online:

- 30 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2025, pp 33-73

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

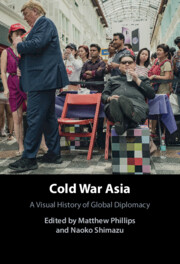

Cold War Asia

- A Visual History of Global Diplomacy

-

- Published online:

- 30 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 February 2025

Image and Anti-Image Covariance Matrices from a Correlation Matrix that may be Singular

-

- Journal:

- Psychometrika / Volume 41 / Issue 3 / September 1976

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2025, pp. 295-300

-

- Article

- Export citation

3 - Where Did Bonaventure Get His Divisions?

- from Part I - Background and Context of the Itinerarium

-

- Book:

- Bonaventure's 'Journey of the Soul into God'

- Published online:

- 23 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 November 2024, pp 96-142

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - There Is Only One World

- from Part III - Intellect

-

- Book:

- Plotinus on the Contemplation of the Intelligible World

- Published online:

- 03 September 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 294-318

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Isolating Time

-

- Book:

- Migration at the End of Empire

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 83-130

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Images of international thinkers

-

- Journal:

- Review of International Studies / Volume 50 / Issue 6 / November 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 May 2024, pp. 1088-1107

- Print publication:

- November 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Dutch moral foundations stimulus database: An adaptation and validation of moral vignettes and sociomoral images in a Dutch sample

-

- Journal:

- Judgment and Decision Making / Volume 19 / 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 April 2024, e10

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Introduction

- from Part I - Mondial Messiaen

-

-

- Book:

- Messiaen in Context

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023, pp 3-9

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

26 - Reconsidering the Tholos Image in the Eusebian Canon Tables: Symbols, Space, and Books in the Late Antique Christian Imagination

-

-

- Book:

- The Intellectual World of Late Antique Christianity

- Published online:

- 05 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 484-515

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 11 - Social Media, Self-Harm, and Suicide

- from Section 2 - Social Media and Mental Health

-

-

- Book:

- Social Media and Mental Health

- Published online:

- 11 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 12 October 2023, pp 109-118

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - The Prose Project

- from Part II - The Literary Works

-

-

- Book:

- W. G. Sebald in Context

- Published online:

- 24 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 07 September 2023, pp 85-92

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Images of depression in Charles Baudelaire: clinical understanding in the context of poetry and social history

-

- Journal:

- BJPsych Bulletin / Volume 48 / Issue 1 / February 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 December 2022, pp. 33-37

- Print publication:

- February 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

13 - Photography and Ethnography

- from Part III - Visual Cultures

-

- Book:

- Decolonizing African Knowledge

- Published online:

- 23 June 2022

- Print publication:

- 14 July 2022, pp 414-450

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - The Visual Turn

-

- Book:

- History and Identity

- Published online:

- 04 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 20 January 2022, pp 203-234

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Theoria and Its Objects

-

- Book:

- Searching for the Divine in Plato and Aristotle

- Published online:

- 09 December 2021

- Print publication:

- 16 December 2021, pp 118-153

-

- Chapter

- Export citation