Refine search

Actions for selected content:

100 results

10 - Irregular War and Warfare

- from Part II - The Traditional Security Agenda

-

- Book:

- Understanding International Security

- Published online:

- 11 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 October 2025, pp 191-209

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Circulating Violence: Guerre contre-révolutionnaire as the Intellectual Foundation of Modern Torture

-

- Journal:

- Comparative Studies in Society and History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 October 2025, pp. 1-27

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

11 - 2012–2014

-

- Book:

- Choosing Defeat

- Published online:

- 07 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2025, pp 327-357

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - 2010–2011

-

- Book:

- Choosing Defeat

- Published online:

- 07 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2025, pp 258-296

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - 2009

-

- Book:

- Choosing Defeat

- Published online:

- 07 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2025, pp 227-257

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - 2007–2008

-

- Book:

- Choosing Defeat

- Published online:

- 07 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2025, pp 161-196

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

16 - Why Did We Lose?

-

- Book:

- Choosing Defeat

- Published online:

- 07 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 October 2025, pp 467-495

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Counterinsurgency

-

- Book:

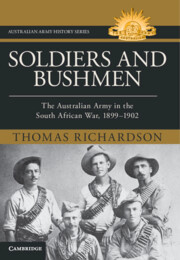

- Soldiers and Bushmen

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 147-172

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Soldiers and Bushmen

- The Australian Army in South Africa, 1899–1902

-

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025

9 - Coups and Communism in Guatemala

-

-

- Book:

- Coups d'État in Cold War Latin America, 1964–1982

- Published online:

- 24 April 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 May 2025, pp 197-214

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Civilian Harm and Military Legitimacy: Evidence from the Battle of Mosul

-

- Journal:

- International Organization / Volume 79 / Issue 2 / Spring 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 July 2025, pp. 332-357

- Print publication:

- Spring 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 18 - The Work of War

- from Part V - Labor

-

-

- Book:

- Latinx Literature in Transition, 1848–1992

- Published online:

- 10 April 2025

- Print publication:

- 17 April 2025, pp 315-332

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Purifying Istanbul: The Greek Revolution, Population Surveillance, and Non-Muslim Religious Authorities in the Early Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Empire

-

- Journal:

- Comparative Studies in Society and History / Volume 67 / Issue 2 / April 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 January 2025, pp. 281-302

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

1 - Weaponizing Displacement in Civil Wars

-

- Book:

- Guilt by Location

- Published online:

- 12 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 1-25

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Depopulation in Syria

-

- Book:

- Guilt by Location

- Published online:

- 12 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 204-237

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - A Sorting Theory of Strategic Displacement

-

- Book:

- Guilt by Location

- Published online:

- 12 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 51-87

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Comparative Evidence of the Sorting Logic

-

- Book:

- Guilt by Location

- Published online:

- 12 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 165-203

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Guilt by Location

- Forced Displacement and Population Sorting in Civil Wars

-

- Published online:

- 12 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024

7 - The Vietnam War and the Regional Context

- from Part I - The Late Vietnam War

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Vietnam War

- Published online:

- 02 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 28 November 2024, pp 163-188

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Conundrum of Pacification

- from Part I - Battlefields

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Vietnam War

- Published online:

- 02 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 28 November 2024, pp 117-132

-

- Chapter

- Export citation