Refine search

Actions for selected content:

13 results

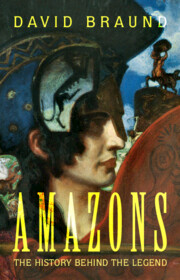

Amazons

- The History Behind the Legend

-

- Published online:

- 26 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 24 April 2025

Chapter 3 - Shades of Dido

-

- Book:

- Propertius and the Virgilian Sensibility

- Published online:

- 28 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 05 December 2024, pp 121-199

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Asian Goddesses and Bees

- from Part III - Anatolian and Aeolian Myth and Cult

-

- Book:

- Aeolic and Aeolians

- Published online:

- 21 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 317-343

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - Honey and Theogonies: The West Face of Sipylus

- from Part III - Anatolian and Aeolian Myth and Cult

-

- Book:

- Aeolic and Aeolians

- Published online:

- 21 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 450-481

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

22 - Curtius’ Alexander

- from Part III - The Historical and Biographical Tradition

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Alexander the Great

- Published online:

- 04 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024, pp 364-378

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Hiding What Must Be Hidden

-

- Book:

- Queering Medieval Latin Rhetoric

- Published online:

- 15 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 05 January 2023, pp 95-112

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 11 - Television and Mass Media

- from Part III - Media and Pop Culture

-

-

- Book:

- Don DeLillo In Context

- Published online:

- 19 May 2022

- Print publication:

- 02 June 2022, pp 109-116

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 13 - Sports

- from Part III - Media and Pop Culture

-

-

- Book:

- Don DeLillo In Context

- Published online:

- 19 May 2022

- Print publication:

- 02 June 2022, pp 126-135

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Alexander in Ancient Jewish Literature

-

-

- Book:

- A History of Alexander the Great in World Culture

- Published online:

- 13 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 03 February 2022, pp 109-142

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Invisible Women: Altered Female Bodies

-

- Book:

- Surgery and Selfhood in Early Modern England

- Published online:

- 11 February 2021

- Print publication:

- 18 February 2021, pp 35-55

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - The Imagined “Savage” Woman

-

- Book:

- Pulp Vietnam

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020, pp 98-132

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part I - Mapping Shakespeare’s World

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 1-66

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Geographical Myths

- from Part I - Mapping Shakespeare’s World

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 24-29

-

- Chapter

- Export citation