4.1 Introduction

United States (US) Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia famously distilled the essence of standing to a four-word inquiry: ‘What’s it to you?’Footnote 1 The law of standing provides standards for evaluating who is a proper party to bring a case to the courts. Standing is a gate-keeping mechanism that seeks to avoid opening the floodgates of litigation and subjecting the courts to frivolous claims. So, in asking, ‘What’s it to you?’ the court is seeking to confirm that only proper parties are permitted to bring claims to help optimise the use of valuable and limited judicial resources.

Standing is jurisdiction-specific. In some jurisdictions, such as the US, a party will not have standing without meeting the requirements of a three-part test. The constitutional origin for this test is the ‘cases or controversies’ language in Article III, Section 2 of the US Constitution. The three-part test evaluates whether (1) the plaintiff has sustained an ‘actual or imminent’ injury that is ‘concrete and particularized’; (2) the plaintiff’s injury is ‘fairly traceable’ to the action or inaction of the defendant; and (3) a favourable decision by the court is likely to redress the plaintiff’s claim.Footnote 2 Unlike the restrictive standing requirements in US and other common law jurisdictions around the world, ‘universal standing’ is the norm in many other jurisdictions, which permits all interested parties to file claims challenging laws that are the alleged sources of their concerns. In some jurisdictions, environmental claims have more relaxed standing requirements than other types of civil claims. There are many other procedural grounds on which the claims may be dismissed, and many ways in which the claims may fail to meet their burdens of proof at trial. Therefore, more permissive standing in climate litigation is important to offer opportunities for meritorious claims to proceed in the courts. The courts are an indispensable last resort in climate litigation in jurisdictions that are plagued by inadequate or non-existent legislative or executive action on climate change matters.

The Urgenda case is a positive step forward in addressing standing in climate litigation.Footnote 3 The standing barrier has precluded many plaintiffs from seeking accountability in the courts from governmental or private sector actors that contribute to climate change.Footnote 4 Yet, in Urgenda, the Court concluded that the Urgenda Foundation had standing to file a collective action claim under the Dutch Civil Code. The Supreme Court noted that the interests of residents of the Netherlands in relation to climate change are sufficiently identical and can be ‘bundled’ to secure protection in a collective action suit. Moreover, the State had not disputed standing in that the claim concerned the protection of the interests of the inhabitants of the Netherlands from dangerous climate change. The State did object to Urgenda’s asserted standing on behalf of people outside the Netherlands and on behalf of future generations. The Dutch government and the Court’s willingness to allow plaintiffs to have standing to bring meritorious climate litigation claims in the courts is a standard towards which the world should aspire in future climate litigation. Ideally, the standard should also include standing on behalf of future generations in climate litigation claims.

Standing is a significant and widely litigated issue in climate litigation around the world and that trend will continue, especially in common law jurisdictions, as the number of these cases continues to rise dramatically.Footnote 5 Strict standing barriers need to be reduced in many jurisdictions around the world to promote broader access to the courts in climate litigation because of the urgency of the climate emergency and the difficulty of asserting individualised harm in climate litigation. There are two primary obstacles for plaintiffs seeking to secure standing in climate litigation. Under US law, one obstacle is the principle that ‘injury to all is injury to none’,Footnote 6 which means that because of the widespread nature of climate change impacts, it is difficult for plaintiffs to allege that the harm that they suffer is sufficiently ‘concrete and particularized’Footnote 7 to satisfy the injury element of standing. Another obstacle that is common to plaintiffs in many jurisdictions is causation – the challenge to attribute climate change impacts to the action or inaction of government and private sector defendants. In recent years, climate attribution science has advanced considerably and will help diminish this obstacle,Footnote 8 though it remains a challenge for many climate litigation plaintiffs.

This chapter reviews cases in several jurisdictions to reveal how courts have addressed standing in climate litigation to date. Section 2 addresses case studies of standing in climate litigation in the US, New Zealand, the European Union (EU), EU Member States, the Philippines, India, and Australia. It reveals how standing has been a barrier to climate litigation in the US, New Zealand, the EU, and the Philippines, whereas standing barriers either do not exist or exist to a lesser degree in several European Member States, India, and Australia. Section 3 identifies emerging best practices to offer recommendations on how future climate litigation claims may avoid dismissal on standing grounds.

4.2 Case Law Developments – State of Affairs

This section describes significant climate litigation cases in several jurisdictions to highlight the range of approaches that courts and tribunals have taken in considering standing in climate litigation. The review of these cases reveals a gap of inconsistent treatment of parties’ ability to seek redress for climate litigation claims. Given the urgency of the climate crisis, and because it is unlikely that there will be frivolous cases seeking to raise ambition in addressing climate change or dealing with its consequences, a more liberalised standard for standing in climate litigation is needed to the maximum extent permissible within the constraints of domestic jurisprudence on standing.

There is a broad spectrum of approaches to standing across jurisdictions. The US represents the most restrictive approach to standing, which requires the constitutional minimum of injury, causation, and redressability to be met for a party to be eligible to proceed with a claim. The US approach to standing is arguably the most stringent, formal, and complex in the world. At the other end of the spectrum are jurisdictions like the European Member States discussed in this section that have adopted a liberal approach in granting standing to climate litigation plaintiffs. A middle category in this range of approaches to standing is reflected in jurisdictions like Australia that allow a lower standing threshold when cases are filed under certain statutes as compared to the higher standing threshold for common law claims. The diversity of approaches along this spectrum is explored in this section.

4.2.1 United States

The approach to standing by US courts is the most restrictive, and it therefore falls at one end of the spectrum. Climate litigation in the US has proceeded against federal and state governmental entities and private sector companies. Climate litigation in the US traces its origins to the landmark case Massachusetts v EPA.Footnote 9 In this case, the US Supreme Court concluded that the state of Massachusetts had standing to seek to compel the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from new motor vehicles, even when the agency had decided not to do so in the exercise of its administrative discretion. The state of Massachusetts brought its claim on behalf of its citizens to seek a remedy for the loss of coastal land in the state due to sea level rise, which is caused by global climate change. This ‘special solicitude’ of the state to bring claims on behalf of its citizens was a significant component of the Court’s analysis in granting standing in the case.Footnote 10

The Court concluded that this alleged injury was both ‘actual’ and ‘imminent’ because it was occurring and was likely to continue to occur. It was also ‘concrete and particularized’ and not abstract or conjectural because it involved scientifically demonstrable loss of land in the state. The second element, causation, was easily established because the defendant, the EPA, conceded it. The final element, redressability, also was satisfied. The Court concluded that although EPA regulations addressing carbon dioxide emissions from new motor vehicles would not stop the loss of coastal land in Massachusetts from sea level rise, it would help slow the rate of loss of that land ever so slightly, which the Court deemed sufficient to meet the redressability standard.Footnote 11

Since Massachusetts v EPA, climate litigation plaintiffs in the US have been plagued by standing barriers in cases against both governmental and private sector defendants. For example, in Native Village of Kivalina v ExxonMobil Corp., the plaintiffs were a traditional Inupiat village of approximately 400 residents living on a remote Arctic strip of land severely compromised by sea level rise and coastal erosion.Footnote 12 The community filed a suit against twenty-three of the leading multinational oil and gas companies, seeking damages for their contribution to global climate change, which, in turn, accelerated the demise of this Native village. The US Circuit Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed the District Court’s dismissal of the case, holding that the plaintiffs lacked standing to bring the claim and that the Court lacked jurisdiction to hear the case due to the political question doctrine.Footnote 13 The Court concluded that the plaintiffs failed on the causation element of standing because they could not show plausible traceability from the defendants’ actions to their injuries.Footnote 14 The Ninth Circuit did not apply Massachusetts v EPA to recognise the unique capacity of the federally recognised Native Village as a quasi-sovereign entity that could benefit from the ‘special solicitude’ reasoning. The Court also highlighted concerns around causation (as related to standing), although perhaps that would not have been the case if the village had the benefit of the more advanced climate attribution science that supports climate litigation today.Footnote 15

Climate litigation against the US federal government in Juliana v United StatesFootnote 16 has also attracted international attention. The youth plaintiffs’ litigation theory, known as ‘atmospheric trust litigation’, asserted an expansive reading of the common law public trust doctrine (to include federal government stewardship of the atmosphere) and the US Constitution (to recognise a right to a stable climate under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment). The plaintiffs in Juliana sought a comprehensive injunctive remedy in the case – a climate recovery plan – based on these ambitious common law and constitutional law theories. In denying the federal government’s motion to dismiss, Judge Ann Aiken’s landmark 2016 decision determined that the atmospheric trust dimensions of the youth plaintiffs’ arguments, and the rights-based arguments under the US Constitution, deserved to proceed to trial.Footnote 17

The Ninth Circuit ultimately dismissed the case in January 2020. Although the Court concluded that the plaintiffs met the injury and causation elements of standing, it held that the plaintiffs failed to meet the redressability element. The Court determined that the youth plaintiffs’ requested remedy to order the federal government to adopt ‘a comprehensive scheme to decrease fossil fuel emissions and combat climate change’ would exceed a federal court’s remedial authority and thus failed to meet the redressability element of standing.Footnote 18

4.2.2 New Zealand

New Zealand represents a slightly less restrictive approach to standing but one that still creates a barrier for bringing a climate case to trial. In New Zealand, climate litigation cases have only discussed standing in the context of public nuisance claims, which require a ‘special interest’ similar to Australia’s special interest requirement (discussed later): (1) the harm must be greater than that to the general public, and (2) the harm must also be particular, direct, and substantial.Footnote 19 The case of Smith v Fonterra Co-Operative Group Ltd illustrates this approach.Footnote 20

Smith, an Indigenous plaintiff who is the climate change spokesman for the Iwi Chairs’ Forum, sued several large New Zealand-based companies over their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. He asserted three tort-based causes of action – (1) public nuisance; (2) negligence; and (3) breach of an inchoate duty – and sought an injunction to require each defendant to reach zero net emissions by 2030. The plaintiff claimed to have interests in lands and other resources that have customary, cultural, historical, nutritional, and spiritual significance to him. In his public nuisance claim, he asserted that anthropogenic climate change will cause sea levels to rise, which will damage his family’s land and interfere with public health, safety, comfort, convenience, and peace.

Under New Zealand law, the Attorney General has standing to sue for an injunction to restrain a public nuisance. The Attorney General can act personally or by way of a relator action in which they act on relation of a private individual or local authority. An individual, meanwhile, can only bring a public nuisance action if they suffer some special damage that is appreciably more serious than that of the general public.Footnote 21 Special damage is considered particular, direct, and substantial, and more than merely consequential.Footnote 22 In this case, Smith chose not to invite the Attorney General to sue on his behalf and instead sued in his own right.

The court of first instance held that Smith’s harm was merely consequential and could not be directly traced to the defendants’ actions due to the long chain of traceability. The Court also held that Smith’s alleged damage was neither particular nor direct to him. Rather, it was a manifestation of the effects of climate change not only on him but also on very many others.Footnote 23

On appeal, Smith alleged that the special damage rule did not account for his interest in the land, as well as the tikanga Māori and his kaitiaki responsibilities, which he asserted were sufficient to set him apart from the general public.Footnote 24 In reevaluating Smith’s claims, the Court addressed the special damage rule, noting that there is no universally accepted formulation. Typically, there are two approaches. The first approach is that the ‘harm suffered by the individual must not only be appreciably different in degree but also different in kind from that shared by the general public’.Footnote 25 The second approach is that ‘all that matters is for the injury and inconvenience to be appreciably “more substantial, more direct and immediate” than that suffered by the general public without necessarily differing in its nature’.Footnote 26

Even when applying the second, more liberal approach to the special damage rule, the Court concluded that Smith lacked standing because he had not suffered any special damage greater than that of other members of the general public, given that many places throughout New Zealand are ‘sites of historical, nutritional, spiritual and cultural significance that are at risk or under threat’.Footnote 27 Smith asked the court to reconsider the special damages rule in its entirety, but the Court reiterated the justifications for the rule, including the prevention of a multiplicity of actions and the premise that the Attorney General is best suited to bring public nuisance claims in accordance with its constitutional role.Footnote 28 The Court ultimately did not decide whether the special damage rule should be abolished. The Court also rejected the ‘nuisance due to many’ argument, wherein defendants who are even partially responsible for damages are held legally accountable based on the extent of their contribution. In rejecting the argument, the Court observed that those principles apply only in cases where there is a ‘finite number of known contributors to the harm, all of whom were before the Court’.Footnote 29

4.2.3 European Union

While the European Court of Justice (ECJ) approach to standing is very specific, it reflects the restrictive approach adopted by the New Zealand courts – and has been subject to extensive criticism. The ECJ recently issued decisions in two significant climate cases that include important standing analysis: Carvalho v European Parliament (‘The People’s Climate Case’)Footnote 30 and Sabo v European Parliament.Footnote 31 The former challenged legislation that sets the EU’s overall climate change targets, whereas the latter challenged legislation that permits a specific measure – reliance on biomass – to meet those targets.

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) organises the EU and governs the laws of locus standi that citizens of Member States have before the ECJ.Footnote 32 TFEU Article 263(4) establishes what constitutes a ‘case or controversy’ before the ECJ in stating that ‘any natural or legal person may … institute proceedings against an act addressed to that person or which is of direct and individual concern to them, and against a regulatory act which is of direct concern to them and does not entail implementing measures’.Footnote 33

The ECJ is tasked with interpreting these standing requirements, and the definition of ‘direct’ and ‘individual’ concern has been developed in ECJ case law. The Plaumann test is the standard applied to evaluate the applicants’ eligibility to challenge the laws at issue. In Plaumann, the ECJ set a high bar to establish individual concern for natural or legal persons. The contested act must affect them ‘by reason of certain attributes that are peculiar to them or by reason of circumstances in which they are differentiated from all other persons, and by virtue of these factors distinguishes them individually just as in the case of the addressee’.Footnote 34 In seeking to meet the Plaumann test, the applicants in the two aforementioned climate cases argued that: (1) any violation of human rights is by its very nature unique or, in the alternative, (2) the test should be altered to take account of the reality of climate change.

In Sabo, a group of individuals and civil society organisations from Estonia, France, Ireland, Romania, Slovakia, and the US challenged a piece of EU legislation that allows the burning of forest biomass, which is considered a renewable energy source under the law. The applicants came from areas that have been particularly affected by logging.

The applicants sought annulment of EU legislation that was allegedly in breach of Article 191 of TFEU and the EU Charter. They argued that the accelerated forest loss and significant increases in forest logging and, consequently, in greenhouse gas emissions violated their right to respect for private and family life, right to education, rights of the child, right to property, health care, freedom to manifest religion, and right to respect for religious diversity. Even though some applicants were foresters or lived in forest areas, the court dismissed the plaintiffs’ claims at the admissibility stage because they failed to establish standing.

In their appeal, the plaintiffs argued that the ‘individual concern’ requirement should be interpreted in view of the reality of the global climate crisis and that, in cases alleging human rights violations, direct access to the ECJ must be ensured, as long as there are no alternatives. The Court rejected this argument, reasoning that the claim that the acts at issue infringed fundamental rights was not sufficient to establish that the plaintiffs’ claims were admissible without rendering the requirements of TFEU Article 263(4) meaningless.Footnote 35 It relied on case law in which strict interpretation of Article 263(4) is consistent with the EU Charter, and with the right to an effective remedy under arts 6 and 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The Court upheld the Plaumann test and continued to bar natural or legal persons from contesting EU environmental law.

In The People’s Climate Case, ten families from Portugal, Germany, France, Italy, Romania, Kenya, Fiji, and the Saami Youth Association, Saminourra, filed a lawsuit against the European Council. The plaintiffs were children and their parents who worked in agriculture and tourism in the EU and abroad and who were increasingly affected by climate change impacts. They argued that three pieces of legislation designed to enable the EU to meet an overall emissions reduction target of 40 per cent compared with 1990 levels were insufficient to protect their lives, livelihoods, and human rights from the impacts of climate change.

The ECJ dismissed the case, holding that the plaintiffs’ claims were inadmissible. Given that the legislative acts at issue were not addressed to the plaintiffs, they had to prove that those acts were of direct and individual concern to them. They argued that they suffered from droughts, flooding, heat waves, sea level rise, and the disappearance of cold seasons. According to settled case law, natural or legal persons satisfy the condition of individual concern only when the plaintiffs are affected in a way that is ‘peculiar to them or by reason of circumstances in which they are differentiated from all other persons, and by virtue of these factors distinguishes them individually’.Footnote 36

The ECJ held that general claims will always concern some fundamental right of some particular applicant. The Court was concerned that allowing such claims to proceed would confer standing to almost any plaintiff. For an annulment action to be declared admissible, it is therefore not sufficient to simply claim that a legislative act infringes fundamental rights. By invoking their fundamental rights, the applicants tried to infer an individual concern from the mere infringement of those rights, on the ground that the effects of climate change are unique to and different for each individual. The Court disagreed with this approach, stating that the legislative acts at issue did not affect the applicants by reason of attributes which are peculiar to them or by reason of circumstances in which they are differentiated from all other persons.

4.2.4 European Union Member States

4.2.4.1 Netherlands

The Netherlands confers standing through a unique civil code provision that grants non-governmental organisations (NGOs) access to its courts.Footnote 37 In Urgenda, the District Court (2015, first instance) held that the Urgenda Foundation met all of the standing requirements to bring the claim, and that it could: a) act on its own behalf, representing the interests of both current and future generations of Dutch citizens; and b) partially rely on the impact of Dutch emissions abroad to establish its own standing, acknowledging the possibility for the Dutch NGO to act on behalf of the interests of persons not resident in the Netherlands: ‘Urgenda can partially base its claims on the fact that the Dutch emissions also have consequences for persons outside the Dutch national borders, since these claims are directed at such emissions.’Footnote 38 However, the Court did not directly address this point. Finding that Urgenda already established its standing on behalf of Dutch citizens, it concluded that ‘no decision needs to be made on whether Urgenda’s reduction claim can als[sic] be successful in so far as it also promotes the rights and interests of current and future generations from other countries’.Footnote 39 The District Court denied the standing of the individual claimants, on the basis that they did not have sufficient interests besides Urgenda’s interest.

The Court of Appeal confirmed the lower court’s decision that the Urgenda Foundation had established its own standing, acting on behalf of the current generation of Dutch nationals and individuals subject to the State’s jurisdiction.Footnote 40 This was because, in the Court’s view, ‘it is without a doubt plausible that the current generation of Dutch nationals, in particular but not limited to the younger individuals in this group, will have to deal with the adverse effects of climate change in their lifetime if global emissions of greenhouse gases are not adequately reduced’.Footnote 41

4.2.4.2 Germany

The Neubauer case concerned a challenge by a group of German youth of the Federal Climate Protection Act. The claimants argued that the target in the Act to reduce GHG emissions by 55 per cent by 2030 from 1990 levels was insufficient to limit global warming to 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels, in line with the Paris Agreement – and therefore violated their human rights.Footnote 42

The claimants included eight German individuals, including some minors who were residents of Germany. They were joined by fifteen individual claimants living in Bangladesh and Nepal. The Constitutional Court recognised the standing of the foreign plaintiffs, finding: ‘The complainants living in Bangladesh and Nepal also have standing in this respect because it cannot be ruled out from the outset that the fundamental rights of the Basic Law also oblige the German state to protect them against the impacts of global climate change.’Footnote 43 However, while the Constitutional Court found a breach of fundamental rights in relation to the resident plaintiffs, the Court established that there could not be a breach of fundamental rights in the case of the non-residents. In the Court’s view, the reduction target of 55 per cent was not itself unconstitutional. However, the Court found that (1) Germany’s emissions must stay within ‘its’ carbon budget; and that (2) its carbon budget would be almost exhausted by 2030 on the basis of the 55 per cent target. The Court therefore found that Germany would need to take very drastic reduction measures after 2030 to stay within its carbon budget, and that these measures would necessarily entail severe restrictions on the fundamental freedoms of the youth plaintiffs (who are residents of Germany). On this basis, the Court established that certain provisions of the Act were incompatible with fundamental freedoms, as they failed to adequately specify emission reductions beyond 2030.

It was therefore because the breach stemmed from the restrictive measures that would be needed to drastically reduce Germany’s GHG emissions (as opposed to the impacts of climate change) that the Court was able to conclude that the complainants living in Bangladesh and Nepal would not be affected in their own freedom (as they would not be subject to such measures).Footnote 44 Accordingly, the Court concluded that ‘no violation of a duty of protection arising from fundamental rights is ascertainable vis-à-vis the complainants who live in Bangladesh and Nepal’.Footnote 45 The Court also noted that the task of fulfilling the duties of protection arising from fundamental rights involves a combination of both climate mitigation and adaptation measures. The judges concluded that Germany would not be able to provide this level of protection through adaptation abroad.Footnote 46

4.2.4.3 Belgium

Under Belgian law, there is a requirement that plaintiffs have a personal and direct interest in the claim. In the case of Klimaatzaak – which was modelled on the Urgenda case – the District Court held (which was confirmed by the Court of Appeal) that both the individual plaintiffs and the NGO satisfied this requirement:

… the diplomatic consensus based on the most authoritative climate science leaves no room for doubt that a real threat of dangerous climate change exists. This threat poses a serious risk to current and future generations living in Belgium and elsewhere that their daily lives will be profoundly disrupted. In this case, the plaintiffs intend to hold the Belgian public authorities partly responsible for the present and future adverse consequences of climate change on their daily lives. In so doing, each of them has a direct and personal interest in the liability action they have brought.Footnote 47

The District Court and Court of Appeal also recognised the standing of the NGO Klimaatzaak to bring the claim, which included rights-based arguments, noting that ‘environmental organisations are given a privileged status by the Aarhus Convention’.Footnote 48

4.2.4.4 France

A court in France issued a decision that also confirmed that Urgenda-like analysis on standing in climate litigation is possible at the national level in European Member States. The Conseil d’Etat, France’s highest administrative court, delivered a powerful decision in Commune de Grande Synthe I regarding France’s obligation to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. The decision could inspire other courts across Europe to review more climate litigation cases.

The Court determined that an individual plaintiff’s claim, which was filed by the Mayor of the municipality in this case, was inadmissible despite his current residence in an area experiencing climate change impacts. The Conseil d’Etat concluded, however, that the municipality of Grande Synthe had the right to challenge the government’s tacit refusal, as its standing resulted from the impact of its ‘direct and certain’ exposure to climate change, and more particularly, sea level rise. The Conseil d’Etat also granted intervention requests in this case from the Paris and Grenoble municipalities due to their ‘very strong’ exposure to climate-related risks.

Commune de Grande Synthe I is a landmark precedent for climate litigation in France and follows the European pathway that was opened in Urgenda. The Conseil d’Etat’s ruling may convince the ECJ to take a less restrictive position on standing in climate litigation. A recent challenge by Paris, Brussels, and Madrid against a Commission regulation on nitrogen oxide emissions has been recently admitted by the General Court and is on appeal before the ECJ as of this writing. This case may be the ECJ’s opportunity to adopt reasoning similar to the Conseil d’Etat’s in Commune de Grande Synthe I.Footnote 49

4.2.5 Philippines

The Philippines is widely regarded for its groundbreaking public interest environmental litigation. Generally speaking, the Philippines falls on the more liberal end of the standing ‘spectrum’.

Championed by the noted lawyer and environmentalist Antonio Oposa, this trendsetting jurisprudence traces its roots to the relaxed standing requirements established in the Minors Oposa case in 1993.Footnote 50 This case was filed as a taxpayers’ class action to compel the Secretary of the Department of Natural Resources to cancel existing timber licensing agreements (TLAs) and refrain from approving new applications. The plaintiffs included Oposa, his children, other children and their parents, and unnamed children of the future. They alleged that all citizens of the Philippines are ‘entitled to the full benefit, use and enjoyment of the country’s virgin tropical forests’Footnote 51 and that they enjoy a constitutional right to a healthful and balanced ecology under Section 16, Article II of the Philippines Constitution.Footnote 52 The plaintiffs asserted that continued authorisation of TLA holders to deforest the Philippines would cause irreparable injury to the plaintiffs, especially the minors and their successors who may never see, benefit from, and enjoy the country’s virgin tropical forests.Footnote 53

The Supreme Court of the Philippines concluded that the plaintiffs had standing to bring the class action. It determined that ‘[t]he subject matter of the complaint is of common and general interest not just to several, but to all citizens of the Philippines. Consequently, since the parties are so numerous, it becomes impracticable, if not totally impossible, to bring all of them before the court’.Footnote 54 The Supreme Court also concluded that the parents, on behalf of the children, correctly asserted that the children represented their generation as well as generations yet unborn.Footnote 55

In the wake of the landmark decision in Minors Oposa, courts in the Philippines have issued several decisions that have been highly protective of environmental resources on behalf of current and future generations. Notwithstanding this leadership in the Philippines court system on public interest environmental litigation, plaintiffs in climate litigation in the Philippines have encountered standing obstacles in recent decisions.

In Segovia v Climate Change Commission,Footnote 56 for example, the plaintiffs sought issuance of writs of kalikasan and continuing mandamus. The writ of kalikasan allows persons filing to do so on behalf of inhabitants prejudiced by alleged environmental damage, whereas mandamus is only available to persons directly aggrieved by the unlawful act or omission.

The plaintiffs represented multiple classes of people, including the car-less, the children of the Philippines, the children of the future, and car owners who would rather not have cars if public transportation were ‘safe, convenient, accessible, or reliable’. The plaintiffs sought to compel the implementation of several environmental laws and an administrative order known as the ‘Road Sharing Principle’, which includes a provision calling for the reformation of transportation and collective favouritism of non-motorised locomotion. The plaintiffs alleged multiple violations including violation of the atmospheric trust provided by the Constitution and failure to implement the Road Sharing Principle mandated by EO 774 and the Climate Change Act. Although the government argued that the plaintiffs violated the hierarchy of courts when they filed their complaint, the Court held that kalikasan is available to persons whose life, health, or property are at risk and allows for circumvention of the typical hierarchy requirements. Therefore, the Court had jurisdiction over the case, and had to determine if the standing requirements were met.

The Court ultimately concluded that the plaintiffs lacked standing on the writ of kalikasan because their allegations amounted to nothing more than ‘repeated invocation of the constitutional right to health and to a balanced and healthful ecology’ and failed to establish ‘a causal link or reasonable connection to the actual or threatened violation of the constitutional right to a balanced and healthful ecology of the magnitude … required of petitions of this nature’.Footnote 57 The Court also dismissed the petition for a writ of mandamus on standing grounds because the plaintiffs failed to prove direct or personal injury.

4.2.6 India

Other jurisdictions in the Global South take a similarly liberal approach to standing. India, for instance, like the Philippines, has a rich history of groundbreaking public interest environmental litigation, which is just starting to serve as a foundation for climate litigation claims in the country. The courts in India analyse standing for public interest litigation with a different lens than traditional private litigation claims. The landmark case on this point, SP Gupta v Union of India,Footnote 58 contains famous language justifying the reasoning for adopting a lower threshold for standing in public interest cases:

This question is of immense importance in a country like India where access to justice being restricted by social and economic constraints, it is necessary to democratise judicial remedies, remove technical barriers against easy accessibility to Justice and promote public interest litigation so that the large masses of people belonging to the deprived and exploited sections of humanity may be able to realise and enjoy the socio-economic rights granted to them and these rights may become meaningful for them instead of remaining mere empty hopes.Footnote 59

Because of this relaxed standard for standing in public interest litigation, plaintiffs in climate cases in India have found particular success with constitutional arguments alleging the right to a clean and healthy environment.Footnote 60

4.2.7 Australia

Australia’s standing jurisprudence makes it a favourable jurisdiction for climate litigation that fits somewhere between the restrictive and liberal jurisdictions discussed so far. Unlike the US where Article III standing requirements (injury, causation, and redressability) always apply to plaintiffs, Australian courts apply narrower common law requirements and broader ‘open standing’ requirements, and their application depends on what statute is at issue. Litigants in Australia enjoy a lower standing threshold when cases are filed under certain statutes as compared to the higher standing threshold for common law claims.

Two statutes that enable lower standing thresholds in Australia are the Environment Protection Act of 1970 (EP Act) and the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act (EPA Act). To secure standing under these statutes, plaintiffs must demonstrate only that their ‘interests are affected by the decision’. These ‘interests’ can include intellectual, emotional, or aesthetic concerns.

By contrast, common law standing (which is controlling in the absence of any relevant statute) in Australia requires that the plaintiff demonstrate a ‘special’ interest by offering proof of some advantage or disadvantage that the plaintiff will incur as a result of the action. The special interest must be more than an intellectual or aesthetic concern and must set the plaintiff apart from other members of the general public.

Two climate cases in Australia effectively illustrate the lower standing thresholds under the aforementioned statutes: Dual Gas Pty Ltd and Ors v Environment Protection AuthorityFootnote 61 and Haughton v Minister for Planning and Macquarie Generation; Haughton v Minister for Planning and TRUenergy Pty Ltd.Footnote 62 In Dual Gas, Australia’s EPA issued a work approval for a power station development, to which three NGOs and an individual, Martin Shield, objected. The tribunal held that three of the four plaintiffs, including Shield, had standing.Footnote 63 It evaluated the plaintiffs’ standing pursuant to a broader definition set forth in the EP Act and the Victorian Courts and Tribunals Act (VCAT Act). Section 33B (1) of the EP Act confers standing to any person whose ‘interests are affected by the decision’ to approve or deny a work proposal. The VCAT Act defines ‘interest’ as an interest of any kind, not limited to ‘proprietary, economic, or financial’ and further allows a person to apply to the tribunal whether their interest is ‘directly or indirectly affected by the decision and whether or not any other person’s interests are also affected by the decision’.Footnote 64

The Tribunal considered three factors to determine if each of the plaintiffs had standing: (1) the nature of the particular project proposal under consideration; (2) the materiality of the project’s potential environmental impact; and (3) the involvement of the plaintiff in the project approval process. The power station’s environmental impact was global in nature as it would increase Victoria’s emission profile by 2.9 per cent by emitting 4.2 million tons of GHGs per year.

Two of the plaintiffs, Environment Victoria (EV) and Shield, were heavily involved in the Dual Gas approval process, while a third plaintiff, Doctors for the Environment Australia (DEA), consisted of members who lived and worked in the Latrobe Valley and would be directly affected by the power station’s presence. The Tribunal also considered the government’s recognition of EV and its wide community constituency, along with Shield’s scientific expertise and the DEA’s participation in international climate change matters through its parent organisation, in its determination of the plaintiffs’ interest in the case. On the other hand, the fourth plaintiff, Locals into Victoria’s Environment (LIVE), submitted an affidavit that referenced only the author’s personal feelings towards the project. The Tribunal held that LIVE’s consistent involvement in opposition to brown coal in general was not enough of an interest to establish standing for this particular case.

The Tribunal provided extensive support for its conclusions. It first noted that the person seeking to establish standing must demonstrate a material connection with the subject matter of the decision under review, that is, a genuine interest. This may arise from a genuinely held and articulated intellectual or aesthetic concern in the particular subject matter of the decision, as opposed to a broader environmental concern generally.Footnote 65 Standing under the VCAT Act is wide but not unlimited. Some meaning must be attached to the words ‘a person whose interests are affected’. Despite the apparent breadth of s 5 of the VCAT Act, Parliament must have intended that rights of review do not accrue to any person.Footnote 66 It is necessary to consider the context of the relevant enabling Act. This requires consideration of the ‘subject, scope and purposes’ of the legislation under which the decision in question was made, and the nature of the reviewable decision itself.Footnote 67

In Haughton, pursuant to the EPA Act, the Minister declared two coal-fired power station project proposals, Bayswater and Mt. Piper, to be ‘critical infrastructure projects’ necessary to meet the electricity needs in New South Wales.Footnote 68 Plaintiff Haughton challenged the declaration and the plan approvals on the grounds that: (1) the Minister erroneously approved the power stations on the basis that they were critical infrastructure projects; (2) the Minister had not fully considered the principles of ecologically sustainable development; and (3) the Minister had not considered the impact of the projects on climate change, which was required of him based on his duty to protect the public interest.

The Court granted standing to Haughton pursuant to the ‘open standing’ requirements of s 123 of the EPA Act, which recognises the right of any person to bring proceedings whether or not any right of that person has been infringed.Footnote 69 The Court also determined that even if it erred in granting open standing to Haughton, he has ‘general (common) law’ standing considering his commitment to being an ‘environmental activist’, his involvement in the approval process via his membership of a small NGO, and his home address location in the floodplain, which will suffer at the hands of the deleterious effects of climate change, exacerbated by the Minister’s approval of coal-fired power plants.Footnote 70 In recognising Haughton’s common law standing, the Court relied on Onus v AlcoaFootnote 71 and North Coast Environmental CouncilFootnote 72 to determine that Haughton had a special interest in anthropogenic effects of climate change beyond that of the interest of a member of the general public.Footnote 73 In essence, standing involves the identification of a legal entity entitled to invoke the jurisdiction of a court.Footnote 74 The open standing provisions found in s 123 of the EPA Act or in s 80(1)(c) of the Trade Practices Act (Cth) embrace the common foundation that the right of any person to bring proceedings arises whether or not any right of that person has been or may have been infringed.Footnote 75

The Dual Gas and Houghton cases reveal Australia’s sliding scale approach to standing in climate litigation by relaxing the standing threshold for plaintiffs pursuing claims relating to climate change impacts of certain projects. Standing for this class of litigants who can demonstrate that their interests are adversely affected by such projects is broad but with safeguards that make it less than universal standing for all potential plaintiffs.

4.3 Emerging Best Practice

There are several principles that constitute emerging best practices for standing in climate litigation. The underlying theme is that existing rules already permit for the granting of standing to climate litigation plaintiffs in most cases, based on the direct, personal, or special interest such plaintiffs have in the issue at stake in the case. This is illustrated by the approach of the courts in several cases to date, including Urgenda, Neubauer, and Klimaatzaak. In other cases, increased liberalisation of standing requirements should be undertaken to ensure that these important claims may be considered as widely as possible in courts around the world. Whether a decision to grant standing is perceived as resulting from a liberal approach or as flowing from a textual interpretation of existing rules, what matters most is that such a decision grants access to justice to those who seek to defend the rule of law.

There are several subparts to what emerging best practices on standing in climate litigation might entail. First, there may be an opportunity in some jurisdictions to create climate litigation exceptions. For example, scholars have argued for a climate litigation exception to the Plaumann test in the EU. The concern with applying this strict test for standing in climate litigation claims is that due to the global nature of the climate problem, an anomalous reality occurs in seeking to establish individual and direct harm: ‘the more serious the harm, the more people affected, the less chance for individual concern – a quite paradoxical outcome’.Footnote 76 Scholars in the US have similarly recognised the anomaly of ‘injury to all should not mean injury to none’ in climate litigation.Footnote 77

In contrast with these suggested approaches, Sabo and The People’s Climate Case represent an unfortunate impediment to much-needed liberalisation of standing requirements to address climate change in the courts. First, the ECJ bypassed an opportunity in these cases to recognise an exception to the Plaumann test in the climate litigation context. Second, the Plaumann test also should be modified for climate litigation claims because it is inconsistent with the EU’s obligation under the Aarhus Convention. Article 9(3) of the Aarhus Convention states that ‘members of the public [must] have access to administrative or judicial procedures to challenge acts and omissions by private persons and public authorities which contravene provisions of its national law relating to the environment’. Moreover, in its 2011 and 2017 reports, the Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee already held that the Plaumann criteria were ‘too strict to meet the criteria of the Convention’ because ‘persons cannot be individually concerned if the decision or regulation takes effect by virtue of an objective legal or factual situation’. Nevertheless, the ECJ did not grant an exception.Footnote 78

Recent developments in climate litigation jurisprudence from European Member States represent emerging best practice in establishing a more liberal standing in climate litigation. There are several dimensions of emerging best practice from these cases.

First, these cases confirm that the ‘injury to all is injury to none’ principle should not apply as a barrier to standing for climate litigation claims. For example, in Neubauer, the Court reached the following conclusion regarding the standing of the youth plaintiffs: ‘The complainants are individually affected in their own freedom. They are themselves capable of experiencing the measures necessary to reduce CO2 emissions after 2030. The fact that the restrictions will affect virtually everyone then living in Germany does not exclude the complainants from being individually affected.’Footnote 79 Similarly, in Klimaatzaak, there is a requirement under Belgian law that plaintiffs have a personal and direct interest in the claim. In this case, the first instance court concluded (which was confirmed on appeal) that both the individual plaintiffs and the NGO satisfy this requirement. The first instance court noted that ‘[t]he fact that other Belgian citizens may also suffer their own damage [from the adverse consequences of climate change], in whole or in part comparable to that of the plaintiffs as individuals, is not sufficient to reclassify the personal interest of each of them as a general interest’.Footnote 80 The Czech court in Klimatická used similar reasoning in establishing the standing of the individual applicants, noting that the individuals ‘must have been directly deprived of [their] rights by the interference’.Footnote 81 Since climate change, despite being a global issue with many victims, has ‘local adverse manifestations’, the Court concluded that citing its wide-ranging effects and pointing to the multitude of victims of those effects ‘does not in itself preclude a direct impairment of the rights of the applicants, who belong to that group’.Footnote 82

Outside of Europe, in Future Generations v Ministry of the Environment and Others, the Colombian Supreme Court determined the standing of the plaintiffs according to four criteria: a) there is a connection between the impairment of the collective and the individual rights; b) the plaintiff is the one directly affected; c) the impairment of the fundamental right must be proven, not hypothetical; and d) the judicial order must re-establish the individual guarantees, and not the collective ones. Twenty-five youth plaintiffs filed a tutela, a constitutional claim used to enforce the protection of fundamental human rights. The Supreme Court held that the youth plaintiffs had standing because their enjoyment of their fundamental rights was ‘substantially linked and determined by the environment and the ecosystem’.Footnote 83

Second, the fact that the most serious climate-related harms will occur in the future has also not prevented European courts from finding that individual and NGO plaintiffs have standing in climate change cases. For example, in Urgenda, the Dutch Supreme Court made some important conclusions regarding the ‘threshold test’ for the State’s obligations under ECHR, which may be useful for establishing standing in other cases:

… the Court of Appeal concluded, quite understandably, in para. 45 that there was ‘a real threat of dangerous climate change, resulting in the serious risk that the current generation of citizens will be confronted with loss of life and/or a disruption of family life’. The Court of Appeal also held, in para. 37, that it was ‘clearly plausible that the current generation of Dutch nationals, in particular but not limited to the younger individuals in this group, will have to deal with the adverse effects of climate change in their lifetime if global emissions of greenhouse gases are not adequately reduced’.Footnote 84

With respect to the State’s obligations to protect the right to life under Article 2 of the ECHR, the Court concluded: ‘The term “immediate” does not refer to imminence in the sense that the risk must materialise within a short period of time, but rather that the risk in question is directly threatening the persons involved. The protection of Article 2 ECHR also regards risks that may only materialise in the longer term.’Footnote 85 Similarly, in Neubauer, the Court made important conclusions regarding the rights of youth plaintiffs to seek recourse for climate harms that would not fully manifest until later in their lifetimes:

As things currently stand, global warming caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions is largely irreversible […]. It cannot be ruled out from the outset that the complainants will see climate change advancing to such a degree in their own lifetimes that their rights protected under Article 2(2) first sentence GG and Article 14(1) GG will be impaired ([…]). The possibility of a violation of the Constitution cannot be negated here by arguing that a risk of future harm does not represent a current harm and therefore does not amount to a violation of fundamental rights. Even provisions that only begin posing significant risks to fundamental rights over the course of their subsequent implementation can fall into conflict with the Basic Law […] This is certainly the case where a course of events, once embarked upon, can no longer be corrected […] The complainants are not asserting the rights of unborn persons or even of entire future generations, neither of whom enjoy subjective fundamental rights […]. Rather, the complainants are invoking their own fundamental rights.Footnote 86

Third, the special interests of youth and future generations have been recognised in these cases to support standing.Footnote 87 The jurisprudence is less clear on whether claims can be brought on behalf of unborn future generations; however, there is now extensive research on the adverse climate impacts that young people alive today will face.Footnote 88

Fourth, it is emerging best practice to enable lower standing thresholds in the context of public interest litigation like climate litigation. India and France have embraced this approach and Australia has applied a version of it in authorising relaxed standing when plaintiffs bring claims under certain environmental statutes. The urgency of the climate crisis and the legislative gridlock in many countries on climate change regulation require that the courts be as available as possible to dispense justice related to climate change issues. Reducing standing barriers is an important step toward achieving this objective.

Other measures to lower standing thresholds include the argument in the Philippines that standing is a procedural requirement that the court can waive in the exercise of its discretion. Allowing courts to waive standing in meritorious climate cases can promote enhanced access to the courts. Another strategy is the tutela in Colombia, which the youth plaintiffs in Future Generations v Ministry of the Environment and Others used to secure standing in a case compelling the Colombian government to ensure zero deforestation and granting legal personhood to the Colombian Amazon.Footnote 89

A jurisdiction that can benefit from this emerging best practice of selective waiver of standing requirements in climate litigation is New Zealand. The special damage rule in public nuisance litigation for climate change issues in New Zealand has prevented meritorious claims from proceeding on standing grounds. A relaxed version of this rule in climate litigation, or waiver of this requirement altogether for climate cases, would be a better approach for New Zealand to adopt in future public nuisance cases for climate change claims so that meritorious cases may proceed to trial to address the climate crisis.

Related to the issue of the special context of standing in climate litigation, the ‘vocational nexus’ theory is one mechanism that can help broaden who is a proper plaintiff in these cases. The Dual Gas and Houghton cases in Australia helped underscore that one’s profession and demonstrated interest and engagement on climate issues can support standing, even though this argument was rejected in the landmark US decision in Lujan v Defenders of Wildlife. Similarly, in Notre Affaire à Tous, the Paris Administrative Court afforded more relaxed standing to environmental NGOs.

Another important dimension of the emerging best practice in this area is to recognise who is bringing the claim and what population is the target of the requested protections. Courts should provide special consideration for sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities who bring climate litigation on behalf of their citizens. This approach was embraced in the ‘special solicitude’ principle in Massachusetts v EPA, but was not applied in the Kivalina case. Standing should also recognise the unique vulnerability of certain populations that may be seeking redress in these cases such as Indigenous communities or youth plaintiffs. The field of climate justice has emerged on the strength of their advocacy and the law of standing needs to catch up in many jurisdictions to enable these vulnerable populations to be considered proper parties to bring these claims. Deserving plaintiffs such as the Indigenous communities in Kivalina (US) and Smith (NZ) and the youth plaintiffs in Juliana (US), Pandey (India), and the People’s Climate Case (EU) had their claims dismissed on standing grounds.

4.4 Replicability

This section provides some reflections on the replicability or otherwise of the emerging best practice discussed earlier.

Some strategic considerations for the near term are important to consider. First, European climate plaintiffs are more likely to succeed by bringing their climate claims in national courts rather than to the ECJ, as evidenced by the outcomes in the Urgenda (Netherlands) and Grande Synthe (France) decisions as compared to The People’s Climate Case (EU). Second, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment ReportFootnote 90 released in August 2021 also should help lower barriers for climate litigation plaintiffs by providing broader scientific foundations for injuries as well as enhanced support for attributing those injuries to GHG contributions from government and private sector action and inaction.

Recent developments around the world on rights of nature also offer promise. Efforts to protect non-human entities (i.e. wildlife and natural resources) from climate impacts may be enhanced by application of mechanisms such as legal personhood and rights of nature protections. Legal personhood protections would confer standing directly to these entities who would then be represented by human guardians in court. Two examples of success on these theories are the Colombia Supreme Court’s assignment of legal personhood in 2018 to the Colombian Amazon to curb deforestation as a primary driver of climate change in a youth climate caseFootnote 91 and the Ecuador Constitutional Court’s decision in 2021 upholding rights of nature protections for Los Cedros Protected Forest.Footnote 92 Two other jurisdictions have not yet succeeded in these efforts. The first example is an effort in Australia to confer rights of nature or legal personhood protections to the Great Barrier Reef as leverage to protect it from continued decimation from ocean acidification and ocean warming.Footnote 93 In the second example, the Belgian court in Klimaatzaak concluded that ‘trees are “not subjects of rights”’ in Belgium and therefore lacked standing to bring a claim.Footnote 94 This case may, however, leave a door open in cases where nature enjoys legal personhood protections in a given jurisdiction.

The Netherlands, as reflected in Urgenda, and other jurisdictions around the world recognise universal standing for associations to bring public interest class actions. While universal standing is a plaintiff-friendly standard for climate litigation and a valuable tool to enhance access to the courts for climate litigation plaintiffs, it may not be the right approach in all jurisdictions that seek to apply standing requirements to safeguard judicial economy and separation of powers.

Proponents of strict standing barriers advance the common argument that such requirements avoid ‘opening the floodgates of litigation’. This argument is more of a perceived than real concern in climate litigation. Even more so than many other forms of litigation, climate litigation is a costly, complex, and time-consuming undertaking for plaintiffs that is not pursued on the basis of whims. In addition to these ‘self-restraint’ barriers that will naturally limit the number of these cases, jurisdictions typically have safeguards in place in their procedural rules to punish frivolous litigation. Finally, even if causation requirements are relaxed for purposes of standing analysis, causation will remain a daunting barrier for climate litigation plaintiffs at trial. Given these three constraints on potential climate litigants, it is unlikely that relaxed standing requirements would overwhelm judicial systems around the world.

A more relevant issue regarding the role of strict standing requirements as a gate-keeping mechanism is the concern over allowing ‘generalized grievances’ to proceed in the court system. The courts have a specific role in promoting justice – they resolve disputes between parties. There is a danger that relaxed standing requirements could transform the courts into a secondary legislative body to address generalised concerns about the government’s policies, which should be taken up directly with the political branches and not addressed in the courts. Climate litigation, however, is not pursued as an end in itself to displace the proper and primary role of political branches in implementing climate governance policy. Rather, it is merely a first step to promote awareness of the need to enhance climate regulation and an opportunity to develop jurisprudence that can better protect litigants from climate change impacts. The ultimate goal of these efforts is to goad future legislative action, not to seek to regulate climate change one case at a time.

Two jurisdictions that require the most reform to enable enhanced standing in climate litigation are the US and the EU. The US maintains that the Article III requirements of injury, causation, and redressability must be met as a constitutional minimum standard in determining who are proper parties in cases or controversies. The EU requires application of the strict Plaumann test in determining who is a proper party to challenge the laws of the EU. In both instances, the existing approaches to standing in these countries have had a chilling effect on plaintiffs seeking to bring climate litigation claims in cases like Juliana in the US and the People’s Climate Case in the EU.

4.5 Conclusion

Standing has been and will remain a controversial feature in climate litigation in the near future in many jurisdictions around the world. While standing upholds important principles of promoting judicial economy, avoiding generalised grievances, and maintaining separation of powers, there is a need to enhance climate litigation plaintiffs’ access to the courts to seek redress of their climate regulation concerns. There are many procedural and substantive bases on which climate litigation claims may fail. Allowing more liberalised standing in these cases merely affords these potentially meritorious claims a better opportunity to be heard.

Easing standing burdens in climate litigation can be guided by the following core principles: (1) climate litigation exceptions to standing requirements may be appropriate in some jurisdictions, building on the approach of reducing standing hurdles for public interest litigation in some jurisdictions; (2) sovereign or quasi-sovereign entities bringing climate litigation claims should have enhanced access to the courts to be able to protect their citizens from climate impacts as in Massachusetts v EPA (US) and Grande Synthe (France); (3) the needs of uniquely vulnerable populations such as Indigenous communities and youth plaintiffs should be considered in evaluating standing thresholds, perhaps similar to international law’s consideration of the ‘special needs of developing nations’; (4) climate plaintiffs should be able to secure standing based on their professional and circumstantial relationships to climate change concerns as in Dual Gas (Australia); and (5) non-human plaintiffs may be able to gain standing in their own right in climate litigation through mechanisms such as legal personhood and rights of nature.

5.1 Introduction

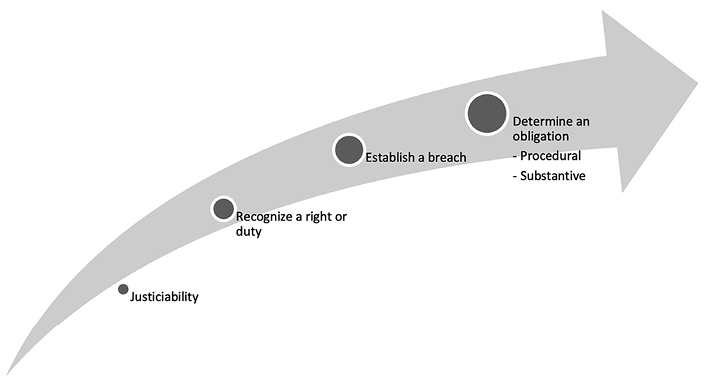

Admissibility could be broadly defined as the group of conditions that render a lawsuit or petition worthy of being reviewed by a judicial or quasi-judicial body, either at the national or international level. Admissibility requirements vary according to jurisdiction and type of legal action but generally relate to procedural requirements. The conflation of the term ‘admissibility’ with similar ones such as ‘jurisdiction’ and ‘standing’ tends to be common. However, some tribunals (including arbitral tribunals) and academics make a distinction by which:

jurisdiction pertains to the ability or power of a […] tribunal to hear a claim, whereas admissibility relates to the characteristics of a particular claim. Accordingly, a tribunal would have to decide, as a primary issue, whether it has jurisdiction, before determining whether a particular claim is admissible. It thus follows that, once a tribunal has upheld a jurisdictional objection, it would dismiss the case and consequently not decide upon objections to admissibility.Footnote 1

Therefore, if jurisdiction reflects a court’s power to adjudicate a dispute, then admissibility pertains to the terms permitting a court to exercise (or decline to exercise) its legal powers. The authorisation to decide whether to adjudicate a dispute which falls under a court’s jurisdiction may be explicitly stated in the court’s constitutive instruments or implicitly derived from them.Footnote 2 Some international legal instruments will also explicitly spell out criteria for admissibility and stress whether the claim before the court constitutes an abuse of legal process or whether it is well founded.Footnote 3 In that sense, courts often find themselves in a position to manage what cases they should or should not dismiss, considering their permanent cautious approach not to arrogate other branches of power’s functions and potentially opening the floodgates to complex climate cases that might be better dealt with in the law-making sphere.Footnote 4

The issue of admissibility is highly relevant to climate litigation because it represents one of the first procedural hurdles for plaintiffs seeking climate-related relief. Accordingly, if the case is dismissed at such an early stage of the legal process, then alleged victims of climate change will, at worst, be left without proper access to justice and, at best, be deprived of discussing the merits of their case. For this reason, broadly speaking, a good emerging practice across different jurisdictions is to balance procedural rigour and consideration of applicants’ particular circumstances in the context of the climate crisis. This chapter focuses mainly on admissibility issues before international and regional human rights courts and bodies, such as the requirement to exhaust domestic remedies, because the legal discussion is more noticeable in those spheres. Additionally, very few national-level cases have addressed the issue of admissibility in detail.

As of May 2021, the climate litigation databases from the Grantham Institute at the London School of Economics and the Sabin Center at Columbia University reported 1,841 ongoing or concluded climate change litigation cases from around the world.Footnote 5 Of these, 1,387 were filed before courts in the United States (US), while the remaining 454 were filed before courts in thirty-nine other countries and thirteen international or regional courts and tribunals (including the courts of the European Union).Footnote 6 About 20 per cent of all the cases (369) reached an outcome, of which 58 per cent (215) were favourable to climate change action, 32 per cent (118) had unfavourable outcomes, and 10 per cent (36) had no discernible likely impact on climate policy.Footnote 7 We can infer from this empirical evidence that at least 68 per cent of settled cases (favourable and no discernible likely impact outcomes) were not precluded by admissibility barriers because they were decided on the merits. Admissibility may have been a factor in the remaining 32 per cent of cases. However, this hypothesis cannot be empirically assessed due to unavailable specific data. Despite this, it is clear from the available evidence that most courts and tribunals worldwide permit cases to proceed to the merits stage of litigation, where substantial aspects are discussed instead of stalling and rejecting the case altogether based on admissibility grounds.Footnote 8

From the point of view of attaining proactive and protective climate action, this trend suggests that, overall, judges are not interpreting procedural admissibility aspects of a legal case as an immediate barrier but rather are adopting a flexible approach to admissibility. Therefore, emerging best practices in the context of admissibility requirements in climate litigation reflect a careful balancing between a rigorous understanding of procedural rules with a sensitivity to the issues at stake in the climate emergency and an understanding of the role of the judiciary in clarifying existing laws that could further climate ambition and protection.

5.2 State of Affairs

Despite the empirical evidence showing that most climate litigation cases succeeded at the admissibility stage, earlier and recent cases have raised important questions about admissibility requirements. These questions, which could play an influential role in the cross-fertilisation of interpretive norms, have been highlighted mainly by international judicial and quasi-judicial bodies specialised in international human rights law. In these cases, the main hurdle has been some established concerns of admissibility requirements, namely the failure of applicants to exhaust domestic remedies, the failure to establish how the alleged facts would characterise a violation of rights, and the failure to clarify the victim’s status. This section will, therefore, explore some of these points in case law.

However, before delving directly into the minutiae of case law, it is important to recall some general aspects of admissibility requirements at the international level, which, to some extent, are also present in many domestic jurisdictions. Comparing the number of cases in the three regional human rights systems, it is conspicuously evident that the European human rights system fares better than its African and Inter-American counterparts regarding the number of petitions admitted and eventually resolved.Footnote 9 This is, however, the result of barriers to access to formal institutionalised justice at the domestic level in Africa and Latin America, mainly due to racial and socioeconomic inequalities, lack of information on the scope of their rights, language barriers, cumbersome lawyer costs and court fees, excessive formalism, procedural delays, and geographical location of tribunals.Footnote 10 After these structural barriers are factored in, admissibility in the regional human rights systems also shows some numeric disparities. In 2014, the European system declared 97 per cent of petitions to be inadmissible; the Inter-American system declared 8 per cent inadmissible; and in the African system, 27 per cent of the cases under consideration were declared inadmissible.Footnote 11 This overview demonstrates that a case’s likelihood of overcoming admissibility barriers will depend on the regional human rights system in which it is adjudicated.

In all international human rights bodies, admissibility is determined through a set of criteria that must be fulfilled cumulatively.Footnote 12 The admissibility criteria applied by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) include criteria related to ratione personae,Footnote 13 loci,Footnote 14 materiae,Footnote 15 and temporis;Footnote 16 characterisations of the claim; exhaustion of domestic remedies; and non-duplication of procedures.Footnote 17 Admissibility criteria for the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) are enumerated in Articles 34–35 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). They are concerned with jurisdictional matters (compatibility of the application or a complaint with the provisions of the ECHR ratione materiae, personae, temporis, and loci), procedural matters (six-month rule and exhaustion of domestic remedies), requirements concerned with the substantive elements of the complaint (manifestly ill-founded and no significant disadvantage criteria), and hybrid criteria that consist both of procedural and substantive elements (requirement of non-repetition and prohibition of the abuse of the right of application), or procedural and jurisdictional criteria (prohibition of anonymous applications).Footnote 18

A notable and early example of how admissibility manifests as a relevant issue in climate litigation can be found in the pioneering petition filed by several Inuit Peoples of the Arctic against the United States before the IACHR in 2005.Footnote 19 In this petition, the Inuit requested the IACHR to recommend that the United States adopt mandatory measures to limit its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, consider the impacts of GHG emissions on the Arctic in environmental impact assessments, establish and implement a plan to protect Inuit culture and resources, and provide assistance necessary for Inuit to adapt to the impacts of climate change that cannot be avoided.

Applicants addressed a potential dismissal of their claim based on admissibility requirements in their petition. They stressed that Article 31.1 of the IACHR’s rules of procedure specifies that the IACHR, to admit the case, ‘shall verify whether the remedies of the domestic legal system have been pursued and exhausted in accordance with the generally recognised principles of international law’.Footnote 20 They also cited the exemptions to the general rule of admissibility, namely that the exhaustion requirement shall not apply when the domestic legislation of the State concerned does not afford due process of law for the protection of the right or rights that have allegedly been violated.Footnote 21 In that vein, the applicants argued that in the US, there are no remedies suitable to address the infringement of their rights, and therefore, the requirement that domestic remedies be exhausted does not apply in their case, meaning consequently that the petition is admissible under the IACHR’s rules of procedure.Footnote 22

A year later, the Assistant Executive Secretary of the IACHR answered the applicants in a letter stating that after having completed the study outlined in Article 26 of the IACHR’s Rules of Procedure, the IACHR determined that it would not be possible to process the petition because the information it contains ‘does not satisfy the requirements set forth in those Rules and the other applicable instruments’.Footnote 23 Specifically, the information provided did not ‘enable the IACHR to determine whether the alleged facts would tend to characterise a violation of rights protected by the American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man’.Footnote 24

Article 26 of the IACHR’s Rules of Procedure concerns the initial review of a petition by the Executive Secretariat of the Commission, who shall be responsible for the study and initial processing of petitions lodged before the Commission that fulfil all the requirements. According to the Executive Secretariat, which served as the first filter of a petition, the applicants did not fulfil the requirements and thus declared it unadmitted.

More recently, on October 12, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) found the communication submitted by sixteen children inadmissible for failure to exhaust domestic remedies under Article 7 (e) of the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This case began in September 2019, when sixteen children from different countries filed a claim alleging that Argentina, Brazil, France, Germany, and Turkey violated their rights under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child because they had not been ambitious enough in reducing their GHG emissions. Specifically, the claimants argued that the countries had failed to take necessary preventive and precautionary measures to respect, protect, and fulfil the claimants’ rights to life, health, and culture, as guaranteed by the Convention.Footnote 25 As a general remark, the CRC recalled that authors must use all judicial or administrative avenues that may offer them a reasonable prospect of redress and that domestic remedies need not be exhausted if they objectively have no prospect of success. For example, in cases where, under applicable domestic laws, the claim would inevitably be dismissed or where established jurisprudence of the highest domestic tribunals would preclude a positive result. However, the CRC noted that mere doubts or assumptions about the success or effectiveness of remedies do not absolve the authors from exhausting them.Footnote 26

In light of this, the CRC found the petitions inadmissible because the authors did not attempt to exhaust all domestic remedies that were reasonably effective and available to them to challenge the alleged violation of their rights under the Convention and that they did not sufficiently substantiate their arguments on the exception under Article 7 (e) of the Optional Protocol that the application of the remedies is unlikely to bring effective relief.Footnote 27