Introduction

Sponsorship landscape and market evolution

Scholars and practitioners have lately shown increased interest in sponsorship because of its capacity to penetrate advertising saturation and enhance consumer–brand connections. Sponsorship transpires when a corporation allocates resources anticipating financial gains via affiliation with events, persons, or organizations (Meenaghan, Reference Meenaghan2013). In 2023, the worldwide sports sponsorship industry was valued at USD 97.35 billion and is anticipated to almost quadruple, reaching USD 190 billion by 2030, with an annual growth rate of 8.68% (Gough, Reference Gough2024). The rapid increase in sponsorship spending has heightened the significance of sponsorship activation – how efficiently sponsors get value from their investments. Sponsorship has historically supplemented conventional methods like advertising, public relations, and hospitality; nevertheless, an increasing share now encompasses digital, mobile, and internet-based platforms (Meenaghan, Reference Meenaghan2013; Ratten, Reference Ratten2024, Reference Ratten2010).

Sponsorship has a twofold purpose: it serves both as a strategic marketing instrument for sponsoring companies and as an essential cash source for sports organizations (Cornwell & Kwon, Reference Cornwell and Kwon2019). Sponsors must deliberately engage relationships to guarantee return on investment (ROI), which should be assessed not just via sales but also in terms of brand equity and awareness (Mastromartino & Naraine, Reference Mastromartino and Naraine2022). This transition has heightened interest in novel activation techniques, especially digital platforms, which provide more precise audience interaction.

Social media as a sponsorship activation mechanism: evidence from Paris 2024

Social media has emerged as the preeminent platform for sponsorship activation, including 98% of all activation channels in the United States (Odell, Reference Odell2017). Platforms like Facebook, Twitter (X), Instagram, and YouTube provide interactive engagement via likes, shares, comments, and live exchanges, rendering them potent instruments for augmenting fan loyalty and sponsor awareness (Hazari, Reference Hazari2018; Meng, Stavros & Westberg, Reference Meng, Stavros and Westberg2015). Social media enables real-time techniques, such as live streaming, live-tweeting, augmented reality, and chatbot engagements, to enhance fan experiences (Enoch, Reference Enoch2020).

Mega athletic events powerfully illustrate this shift. The Olympic Games, probably the largest global multi-sport event, provide an ideal context for analyzing sponsorship activation due to their unmatched reach and cultural importance (Florek, Breitbarth & Conejo, Reference Florek, Breitbarth and Conejo2008). Social media has significantly transformed Olympic consumption, transitioning audiences from passive observation to active participation (Voorveld, Van Noort, Muntinga & Bronner, Reference Voorveld, Van Noort, Muntinga and Bronner2018).

The Paris 2024 Olympics, characterized as the ‘Most Social Olympic Games to Date’, were a pivotal moment. The International Olympic Committee has shifted from its traditionally restricted media strategy, allowing athletes and staff to disseminate sponsor-related information across various channels, thereby personalizing the Games and enhancing viral involvement. The outcomes were significant: in the first week of Paris 2024, @Olympics accounts achieved 34.16 million interactions, representing a 354% increase from Tokyo 2020, and acquired 2.7 million new followers – a 285% rise compared to Tokyo (Vernon, Reference Vernon2024). Paris 2024 exemplifies the intersection of sponsorship, internet platforms, and consumer engagement in the contemporary sports economy.

Research gap and study objectives

Despite increasing academic interest in sponsorship and digital media, there is a paucity of research investigating the direct impact of consumers’ social media use on their involvement with sponsors. Previous research has mostly focused on sponsorship outcomes, including attitudes toward sponsoring companies and purchase intentions (Koronios, Ntasis & Dimitropoulos, Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2022), or on the utilization of social media by athletes and brands during events (Agrawal, Gupta & Yousaf, Reference Agrawal, Gupta and Yousaf2018). However, the viewpoint of consumers – especially the distinction between heavy and light social media users – remains little examined. This limited attention to digital mediation reflects a significant gap in the literature. While prior studies have assessed sponsorship outcomes and consumer attitudes, few have empirically examined how social media usage functions as a mediating mechanism that connects sponsorship antecedents to engagement outcomes. This research addresses this void by presenting the first empirically tested framework that positions social media usage as a mediator in the sponsorship process during mega-events such as the Olympics.

This study introduces the first empirical framework that integrates social media usage as a mediating variable between key sponsorship antecedents and engagement outcomes within the setting of a mega-sporting event – the Paris 2024 Olympic Games. By doing so, it addresses a critical gap in the literature on digital sponsorship strategy in large-scale events. This research examines how social media use influences the link between essential sponsorship antecedents (e.g., sport participation, event attachment, sponsor sincerity, sponsor-event congruence) and consumer engagement with sponsors. This study enhances sponsorship theory and practice by pursuing three objectives:

i. To evaluate the impact of sport sponsorship antecedents on consumer interaction with sponsors.

ii. To investigate the impact of consumers’ social media use on engagement levels, contrasting heavy users with non-heavy users.

iii. To provide theoretical and practical insights that may assist researchers, sponsors, and sports organizations.

To accomplish these objectives, we present a cohesive conceptual framework that synthesizes literature on sponsorship, sporting events, and social media, underpinned by 14 hypotheses. This research enhances the comprehension of sponsorship effectiveness in mega-events like the Olympics by including social media use as a mediating variable.

Theoretical background

Social media serve as a significant venue for sponsorship investment and activation, functioning as effective channels for brand-consumer interaction. Social media offer various channels that enable real-time communication and engagement between consumers and brands. Compared to traditional media, the unique characteristics of social media, including constant availability and the immediacy of interactions among engaged and empowered consumers, necessitate an alternative monitoring and measurement framework to address these dynamics (Meenaghan, Reference Meenaghan2013). Given the ongoing and dynamic discourse regarding measurement and metrics in social media, it is pertinent to analyze the current state of sponsorship research within this field at this stage of its evolution. The recent Paris 2024 Olympic Games served as a focused demonstration of social media utilization among spectators, sponsors, athletes, and the event itself.

Social media have consistently served as a critical element for marketing researchers in elucidating audience behavior. Research indicates that men and women engage with social media for distinct motivations. Women primarily utilized social media for interpersonal interaction, whereas men were more inclined to seek information through these platforms. Furthermore, in comparison to social media users, nonusers exhibited lower economic stability, diminished social support, and restricted technology skills (Tang & Cooper, Reference Tang and Cooper2017).

Sports media, especially in the context of mega-events, represents a significant field of study due to its distinctive influence on the formation of public opinions and behaviors (Billings & Hardin, Reference Billings and Hardin2013). Researchers suggested that sport mega-events often promote a societal image. The audience’s experience with sport mega-events extends beyond the context of the Games, influencing and being influenced by their comprehension of identities and the prevailing values within a society (Tang & Cooper, Reference Tang and Cooper2017). Hutchins and Rowe (Reference Hutchins and Rowe2012) emphasized that evolving audience behavior during sports events has fundamentally transformed the understanding of these events, highlighting the necessity for increased academic focus on changes in audience sports consumption patterns. Understanding the reasons and mechanisms behind social media usage during major sporting events is essential for identifying its impact on the relationship with sports media, shaping individual opinions and behaviors, and influencing the effectiveness of sponsorships (Raney & Bryant, Reference Raney and Bryant2009). The influence of social media within the sports industry is significant. Previous studies have investigated the motivations for consumer engagement in sport (Koronios & Dimitropoulos, Reference Koronios and Dimitropoulos2020) and fan responses to different types of social media posts (Anagnostopoulos, Parganas, Chadwick & Fenton, Reference Anagnostopoulos, Parganas, Chadwick and Fenton2018), including posts related to sponsors (Weimar, Holthoff & Biscaia, Reference Weimar, Holthoff and Biscaia2020). Researchers have identified the enthusiasm social media users exhibit for their preferred sports brands, the conversational networks they establish, and the specific times during the day and week when users are most engaged (Naraine, Bakhsh & Wanless, Reference Naraine, Bakhsh and Wanless2022). These advances have been significant as they allow marketers to assess the relevance of social media campaigns to their audiences and to enhance engagement with those campaigns in what Watanabe, Shapiro and Drayer (Reference Watanabe, Shapiro and Drayer2021) termed a ‘like economy’.

Sport involvement

Involvement refers to the degree to which an individual views a particular item or activity as important, meaningful, and engaging in their lifestyle (O’Cass, Reference O’Cass2000). Sports involvement is characterized as an unobservable state of motivation, arousal, or interest that arises during the observation of a game or engagement in sport-related activities. This state influences behaviors including information searching, processing, and decision-making (Trivedi, Soni & Kishore, Reference Trivedi, Soni and Kishore2020). The concept of sports involvement is essential for analyzing the behaviors and attitudes of sports fans. It is pivotal to the success of sports events, enhances sponsorship outcomes (Meenaghan, Reference Meenaghan2013), improves perceptions of corporate image, and boosts game attendance (Koronios et al., Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2022). Moreover, elevated levels of sports participation correlate significantly with heightened customer brand engagement, as demonstrated by improved awareness, recognition, and recall (Koronios, Ntasis & Dimitropoulos, Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2024). This association is linked to increased enjoyment of events (Bojanic & Warnick, Reference Bojanic and Warnick2011). From a Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT) perspective, sport involvement reflects purposeful media use, where individuals seek emotional, informational, and identity-based gratifications through their interaction with sport (Osokin, Reference Osokin2019). Simultaneously, Relationship Marketing Theory frames this involvement as a foundation for trust-building, whereby the personal importance placed on sport increases the likelihood of forming durable relationships with sponsoring brands that align with the spectator’s values (Abeza, O’Reilly & Reid, Reference Abeza, O’Reilly and Reid2013). Engagement in sports markedly affects consumers’ purchase intentions regarding sponsors’ products (Bachleda, Fakhar & Elouazzani, Reference Bachleda, Fakhar and Elouazzani2015). Empirical studies indicate that involvement serves as a mediator in the relationship between online user-generated content and brand perceptions. The significant effects highlight the role of sports involvement as a crucial factor in sports marketing research. The motivational foundation of sport involvement can also be explained through Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which posits that individuals are driven to act when their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are fulfilled. Spectators with high sport involvement often choose to follow sports freely (autonomy), feel knowledgeable and capable in understanding events (competence), and connect with a like-minded community (relatedness) (Bernhart, Wilcox, McKeever, Ehlers & O’Neill, Reference Bernhart, Wilcox, McKeever, Ehlers and O’Neill2025). These psychological drivers may deepen their connection with the sport and, by extension, increase their openness to sponsor messaging embedded in the sport environment. Building upon the information provided earlier, the following research hypothesis is formulated:

H1: Spectators’ involvement with sport is expected to affect their engagement with sponsors

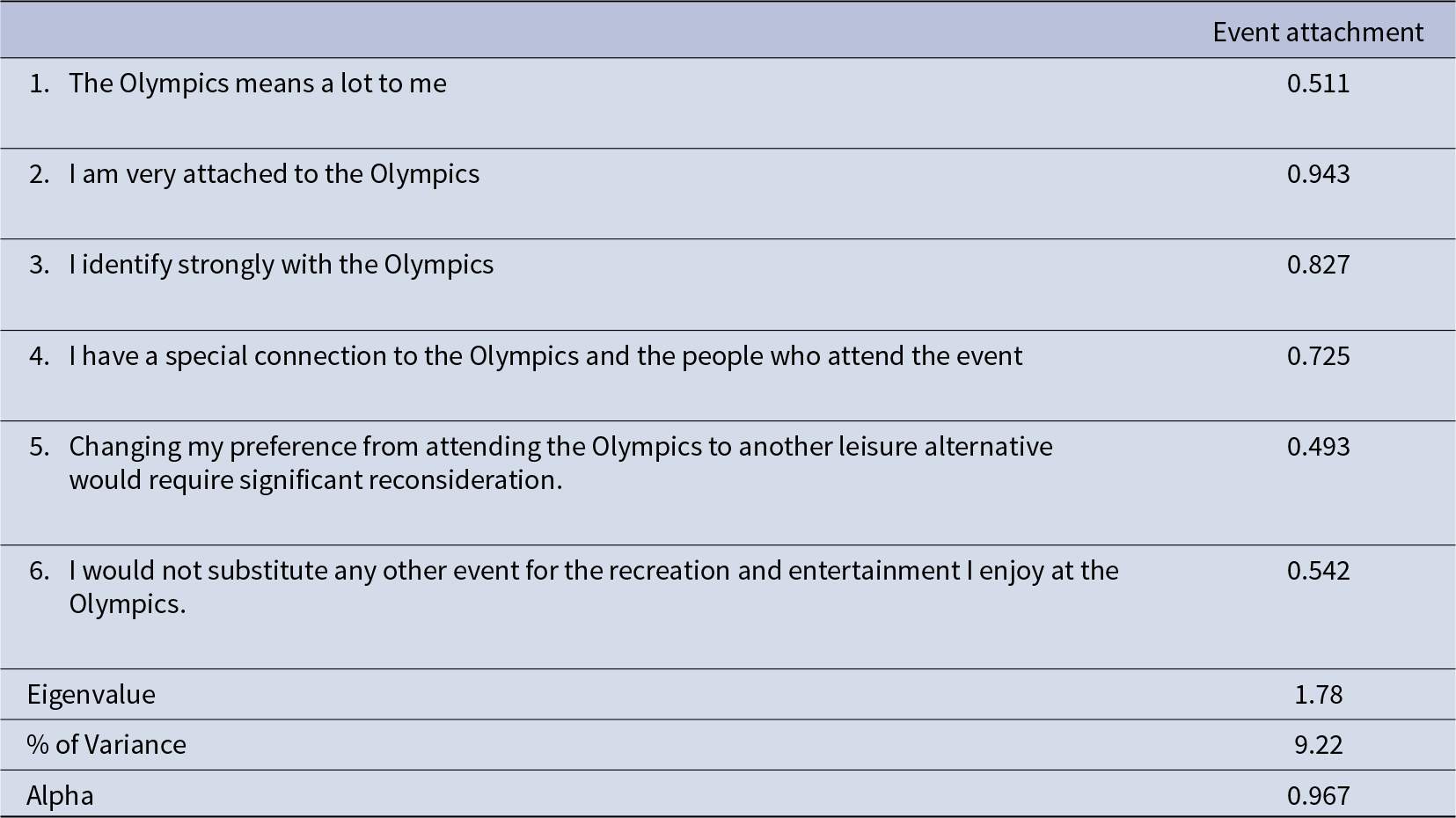

Event attachment

Attachment in marketing literature is defined as the human inclination to form bonds, develop attachments, or seek a strong emotional connection (Moharana, Roy & Saxena, Reference Moharana, Roy and Saxena2023). This state is characterized by intrinsic motivation, wherein the physical and psychological attributes of the entity hold significance for the consumer (Dwyer, Mudrick, Greenhalgh, LeCrom & Drayer, Reference Dwyer, Mudrick, Greenhalgh, LeCrom and Drayer2015). From an SDT perspective, event attachment reflects the fulfillment of psychological needs such as relatedness and belonging. This helps explain why spectators who feel emotionally connected to an event may be more receptive to sponsor messaging embedded in that experience (Bernhart et al., Reference Bernhart, Wilcox, McKeever, Ehlers and O’Neill2025). This aspect is relationship-based and indicates the psychological attachment of consumers to an entity, such as an event (Ouyang, Gursoy & Sharma, Reference Ouyang, Gursoy and Sharma2017). The relationship involves both cognitive and affective dimensions between the object and the individual, alongside positive emotions and experiences associated with the object (Okayasu, Oh & Morais, Reference Okayasu, Oh and Morais2020). Moreover, emotion plays a crucial role in the attachment process, with event spectators experiencing heightened emotions. Event attachment refers to the inclination of participants to engage with an event, influenced by factors such as its atmosphere, overall appearance, and the demographics of the attendees (Okayasu et al., Reference Okayasu, Oh and Morais2020).

Research demonstrates that spectators of events can develop attachments to event-specific items, including apparel, symbols, and rituals, which serve as means of self-expression (Scheinbaum, Lacey & Drumwright, Reference Scheinbaum, Lacey and Drumwright2019). Consumers of a sporting event may develop an attachment to the event through a sense of allegiance to the specific sporting activity, including the team or fellow spectators (Funk & James, Reference Funk and James2006). Research in sports marketing indicates that attachment to sports clubs, teams, and events leads to favorable behaviors (Ouyang et al., Reference Ouyang, Gursoy and Sharma2017). Event spectators who exhibit a significant level of interest and have positive experiences cultivate a sense of affiliation, allegiance, and attachment. Attachment to events may enable individuals to express their self-identities. Attachment to events facilitates the development of vivid memories linked to the event, thereby enhancing motivation to engage in event-related activities, including interactions with sponsors (Sung et al., Reference Sung, Kang, Moon, Choi, You and Choi2021).

SDT also offers a useful lens for understanding emotional attachment to events. Mega-events like the Olympics are immersive experiences that allow spectators to form emotional bonds through social participation, symbolic rituals, and national pride (Bernhart et al., Reference Bernhart, Wilcox, McKeever, Ehlers and O’Neill2025). These experiences satisfy relatedness and identity needs, reinforcing internal motivation and creating meaningful memories. As spectators internalize the emotional significance of the event, their attachment may translate into a stronger receptivity to associated sponsors and brands. Drawing from the preceding context, the following research hypothesis is postulated:

H2: Spectators’ attachment to the event is expected to affect their engagement with sponsors

Subjective event knowledge

Consumer knowledge significantly influences consumer behavior, including information processing and information search (Cervi & Brei, Reference Cervi and Brei2022). It denotes the pre-existing knowledge or information retained in a consumer’s memory that substantially impacts information search, evaluation, memory, and decision-making (Hochstein, Bolander, Christenson, Pratt & Reynolds, Reference Hochstein, Bolander, Christenson, Pratt and Reynolds2021). This reflects an individual’s feelings, beliefs, or confidence regarding their knowledge, commonly referred to as self-perceived knowledge (Cervi & Brei, Reference Cervi and Brei2022). Previous literature identifies three types of knowledge: objective knowledge, subjective knowledge, and usage experience. These types are positively correlated yet conceptually distinct (Flynn & Goldsmith, Reference Flynn and Goldsmith1999). Objective knowledge constitutes the factual information retained in an individual’s memory, whereas subjective knowledge pertains to consumers’ perceptions of their own knowledge (Flynn & Goldsmith, Reference Flynn and Goldsmith1999). Subjective knowledge refers to consumers’ perceptions of their understanding regarding a product, brand, or purchasing decision, in contrast to objective knowledge. Consumer awareness of subjective knowledge significantly impacts information processing, knowledge-sharing intentions, and related consumption behaviors more directly than other knowledge forms (Moharana et al., Reference Moharana, Roy and Saxena2023). Self-concept and image are predominantly shaped by individuals’ perceptions and feelings regarding themselves (Hochstein et al., Reference Hochstein, Bolander, Christenson, Pratt and Reynolds2021), rather than by objective facts and knowledge retained in memory. This aligns with SDT, where perceived competence (as reflected in self-assessed knowledge) enhances spectators’ intrinsic motivation to engage with event-related content (Bernhart et al., Reference Bernhart, Wilcox, McKeever, Ehlers and O’Neill2025). In sponsorship contexts, this suggests that individuals with higher subjective knowledge may feel more confident and autonomous in interpreting sponsor messages and forming brand-related judgments. This research emphasizes the significance of subjective event knowledge over objective event knowledge, given the established connection between subjective knowledge and consumer decision-making.

As consumers move from passive interactions to active decision-making in their consumer journey, they integrate their existing knowledge with new information about the specific product or brand. The integration of existing knowledge with newly developed information results in subjective knowledge that may lack precision, comprehensiveness, and depth (Hochstein et al., Reference Hochstein, Bolander, Christenson, Pratt and Reynolds2021). Subjective knowledge of event sponsorships encompasses the understanding developed through an individual’s prior knowledge and experiences related to an event and its sponsors. Given the preceding information, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Spectators’ subjective event knowledge is expected to affect their engagement with sponsors

Brand familiarity

Brand familiarity denotes a consumer’s direct personal experiences, such as being a customer of the brand, as well as indirect experiences, including exposure to brand advertising (Marti-Parreno et al., Reference Martí-Parreño, Bermejo-Berros and Aldás-Manzano2017). According to Park and Stoel (Reference Park and Stoel2017), brand familiarity is characterized as a unidimensional construct that is associated with the duration of time allocated to processing information regarding the brand, regardless of the nature or content of the processing. Ha and Perks (Reference Ha and Perks2005) define familiarity as the aggregation of product-related experiences acquired by a consumer. This term functions as a broad concept, related to but separate from other significant constructs, including consumer expertise, prior knowledge, and belief strength. Familiarity is regarded as a necessary, albeit insufficient, condition for the development of expertise and the successful execution of product-related tasks.

In line with Engagement Theory, familiarity reduces cognitive resistance and increases the ease with which individuals interact with brand messages, facilitating deeper affective and behavioral engagement (Schönberner & Woratschek, Reference Schönberner and Woratschek2023). Relationship Marketing Theory also supports this, suggesting that brand familiarity enhances trust formation and increases the likelihood of long-term sponsor-consumer relationships (Abeza et al., Reference Abeza, O’Reilly and Reid2013). Research on brand familiarity within the realm of online consumer behavior is limited. Menon and Kahn (Reference Menon and Kahn2002) propose that when customers find online encounters enjoyable, they are more inclined to interact further, demonstrating a positive association with brand familiarity. Moreover, brand familiarity has been shown to diminish the need for information retrieval; Morrin and Ratneshwar (Reference Morrin and Ratneshwar2000) discovered that consumers allocate less time to purchasing for known brands than for new ones. Consumer relationships with recognized brands are often more robust and enduring than those with new brands (Koronios, Ntasis & Dimitropoulos, Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2023). In sports sponsorship, a significant degree of viewers’ brand familiarity with a sponsoring entity may more successfully improve consumers’ attitudes toward and knowledge of the brand than simple sponsorship exposure (Walraven, Koning & van Bottenburg, Reference Walraven, Koning and van Bottenburg2012). The level of brand familiarity may substantially affect customer interaction with sponsors. Building upon the information provided earlier, the following hypothesis is posited:

H4: Spectators’ familiarity with the sponsoring brand is expected to affect their engagement with sponsors

Sincerity

Perceived sponsor sincerity refers to consumers’ evaluation of the altruistic intentions underlying a sponsorship (Speed & Thompson, Reference Speed and Thompson2000). The formation of positive attitudes toward a sponsor is influenced by the consumer’s attribution of sponsorship motives, particularly when the sponsor is perceived as sincere (Becker-Olsen & Hill, Reference Becker-Olsen and Hill2006). Consumers frequently classify a company’s sponsorship motives as either public-serving, which provides advantages to individuals external to the firm, or firm-serving, which mainly benefits the firm itself (Becker-Olsen & Hill, Reference Becker-Olsen and Hill2006). When a firm is viewed as having public-serving motives, consumers are more inclined to trust the firm’s genuine interest in supporting the sponsored property, thereby maintaining a favorable image of the firm. The perceived sincerity enhances positive consumer attitudes toward the firm. Within the framework of Relationship Marketing Theory, sincerity fosters trust and strengthens the emotional bond between consumers and brands (Abeza et al., Reference Abeza, O’Reilly and Reid2013). Sincere sponsorship is perceived as value-driven rather than profit-driven, leading to greater consumer identification with the sponsor and deeper engagement over time. Conversely, when consumers perceive sponsorship as a profit-driven strategy, they may develop skepticism regarding the firm’s altruistic motives, resulting in less favorable impressions (Kang & Matsuoka, Reference Kang and Matsuoka2022). Previous studies indicate that a strong perception of sincerity enhances favorable attitudes toward the sponsor (Koronios et al., Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2023). Drawing from the preceding context, the following research hypothesis is postulated:

H5: Spectators’ anticipated degree of sponsors’ sincerity is expected to affect their engagement with sponsors

Ubiquity of the sponsor

The sponsorship of multiple sports properties by a firm may negatively impact the perceived sincerity of the firm due to the perception of profit-driven motives. The potential effect can be analyzed using covariation theory, which suggests that individuals derive causal inferences from accumulated information across three dimensions: consensus, consistency, and distinctiveness (Kelley, Reference Kelley1967). Distinctiveness, a key factor in determining the causes of actions, pertains to the consistency of an actor’s behavior across various entities (Way, Conway, Shockley & Lineberry, Reference Way, Conway, Shockley and Lineberry2021). High distinctiveness arises when an actor interacts with one entity in a manner that differs from interactions with other entities. The interaction’s cause is ascribed to the entity itself, indicating that the actor possesses a genuine concern for the entity (Pöyry, Pelkonen, Naumanen & Laaksonen, Reference Pöyry, Pelkonen, Naumanen and Laaksonen2019).

In contrast, low distinctiveness, characterized by an actor interacting with multiple entities in a similar fashion, indicates that the cause is inherent to the actor. Individuals attribute self-interested motives to the actor, inferring that the actor’s nature is the fundamental cause of the interactions (Kang & Matsuoka, Reference Kang and Matsuoka2022). In the context of sponsorship, high distinctiveness indicates that a firm sponsors only one sports property, which suggests reduced ubiquity. In these scenarios, consumers may associate the sponsorship with intrinsic qualities of the property, viewing the sponsor’s intentions as genuinely supportive or oriented toward public service. This perception cultivates positive attitudes toward the sponsor. From a Relationship Marketing lens, ubiquity may increase brand recall and facilitate stronger associations across different touchpoints (Abeza et al., Reference Abeza, O’Reilly and Reid2013). However, Attribution Theory reminds us that excessive visibility may dilute perceived authenticity, as consumers begin to question the sincerity of sponsor motives if exposure feels overly commercialized or insincere (Popp, Sattler, Pierce & Shreffler, Reference Popp, Sattler, Pierce and Shreffler2022). Conversely, low distinctiveness, characterized by a firm sponsoring numerous sports properties (high ubiquity), prompts consumers to deduce that the sponsor’s motives are primarily profit-driven rather than reflective of the unique attributes of the properties. Consequently, the perceived sincerity of the sponsor is reduced, resulting in less favorable consumer attitudes toward the sponsor. Building upon the analysis presented earlier, the following hypothesis is posited:

H6: Spectators’ anticipated degree of sponsors’ ubiquity is expected to affect their engagement with sponsors

Congruence

Congruence denotes the extent of similarity between two objects or activities (Henderson, Mazodier & Sundar, Reference Henderson, Mazodier and Sundar2019). The congruity principle posits that information that is congruent is more readily recalled and favored compared to incongruent information. Congruence can strengthen associative links, increase memory activation, and improve the accessibility of attitudes. Congruence between a brand and a property, often termed fit, similarity, relatedness, linkage, or matchup, is a crucial element in both industry and academic sponsorship research (Gálvez-Ruiz, Lara-Bocanegra, García-Fernández & Núñez-Sánchez, Reference Gálvez-Ruiz, Lara-Bocanegra, García-Fernández and Núñez-Sánchez2025; Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Mazodier and Sundar2019). Gwinner and Bennett (Reference Gwinner and Bennett2008) classify fit into two categories: functional fit, in which the sponsoring brand’s product is utilized in the events of the sponsored property (e.g., Coca-Cola’s sponsorship of the Paris 2024 Olympics), and image-based fit, where the brand and the property exhibit similar images (e.g., Omega’s sponsorship of the Paris 2024 Olympics). Furthermore, fit encompasses brands and properties that align in values, missions, or target demographics (Becker-Olsen & Hill, Reference Becker-Olsen and Hill2006). Congruence enhances cognitive consistency as consumers evaluate information regarding a brand’s actions (Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Mazodier and Sundar2019). This cognitive harmony is well grounded in Cognitive Consistency Theory, which suggests that when brand and event identities align, spectators are more likely to accept and internalize sponsorship messages (Aguiló-Lemoine, Rejón-Guardia & García-Sastre, Reference Aguiló-Lemoine, Rejón-Guardia and García-Sastre2020). Engagement Theory further proposes that this alignment promotes narrative immersion, increasing spectators’ emotional investment in both the event and the sponsor (Schönberner & Woratschek, Reference Schönberner and Woratschek2023).

In sponsorship agreements, congruence evaluates the alignment between the sponsor and the sponsored entity. This congruence arises from the alignment between the pertinent characteristics of the sponsor and the attributes of the sponsored entity (Mishra, Roy & Bailey, Reference Mishra, Roy and Bailey2015). Therefore, a sponsoring firm that closely matches the characteristics of the sponsored entity can establish a robust association. This study posits that consumer responses and engagement will be enhanced by a strong alignment between the sponsoring firm and the sponsored club. Building upon the analysis presented earlier, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H7: Spectators’ anticipated degree of congruence between sponsor and sponsored event is expected to affect their engagement with sponsors

Social media usage

Social media have attracted significant attention from scholars and professionals because of their ubiquity and cultural influence. Consumers engage with social media at various stages of the consumption process, including information search, decision-making, word of mouth, and the acquisition, use, and disposal of products and services. Numerous definitions of social media engagement exist within the academic literature (Schivinski, Reference Schivinski2019). Mirbagheri and Najmi (Reference Mirbagheri and Najmi2019) characterized consumer engagement in a social media activation campaign as the total cognitive, affective, and behavioral energies that consumers invest in the campaign simultaneously and holistically. Cognitive engagement encompasses all mental activities related to consumers’ interest in and comprehension of a subject. Affective engagement is defined by the presence of excitement and pleasure associated with the object of engagement. Behavioral engagement encompasses active expressions, including sharing, learning, and endorsing behaviors (Dessart, Veloutsou & Morgan-Thomas, Reference Dessart, Veloutsou and Morgan-Thomas2015). Another perspective on social media engagement considers it as behavioral expressions toward a campaign that arise from motivational factors. The behavioral dimension of social media engagement concerning campaign-related activities, such as liking, commenting, posting, and sharing, has been utilized as an indicator of engagement (Schivinski, Reference Schivinski2019).

Social media usage has become a prevalent activity among Internet users (Dessart et al., Reference Dessart, Veloutsou and Morgan-Thomas2015), offering sports clubs and their sponsors an additional avenue for engaging with supporters and consumers. In this context, various sports organizations consistently interact with their supporters and followers via multiple social media platforms. Individuals use social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to obtain essential information, assist in decision-making and purchasing, engage with others, share information, and seek entertainment (Voorveld et al., Reference Voorveld, Van Noort, Muntinga and Bronner2018). From a UGT perspective, social media is not a passive medium but one actively used by individuals to satisfy emotional, informational, and relational needs during mega-events. It facilitates parasocial interaction, where fans develop imagined relationships with teams, athletes, or brands, thereby intensifying their emotional attachment and driving higher engagement levels with sponsoring brands (Osokin, Reference Osokin2019). In this context, various sports organizations consistently interact with their supporters and followers via multiple social media platforms. Building upon the analysis presented earlier, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H8–14: Spectators’ degree of social media usage mediates the relationships between spectators’ involvement with sport, attachment with the event, subjective event knowledge, brand familiarity, anticipated degree of sponsors’ sincerity and ubiquity, anticipated degree of sponsor-event congruence, and spectators’ engagement with sponsors.

Engagement with sponsors

Engagement constitutes a critical component of sport marketing and sponsorship. The relationship between consumers and brands is interactive and essential for the development of communities that brands aim to establish with consumers (Naraine et al., Reference Naraine, Bakhsh and Wanless2022). Engagement commences with a consumer’s activity or action, succeeded by a subprocess in which they share experiences, advocate for the brand, or interact with other consumers regarding the brand. The results of these activities produce enhanced consumer satisfaction, increased brand loyalty, and elevated trust and commitment, which contribute to future consumption behaviors (Dolan, Conduit, Fahy & Goodman, Reference Dolan, Conduit, Fahy and Goodman2015; Ratten, Reference Ratten2016).

The concept of sponsorship engagement with sponsors was defined by assessing respondents’ awareness of sponsors, their attitudes toward sponsors, and their intentions to purchase the sponsors’ products. The elements align with the three distinct levels of the hierarchy of effects model (Barry, Reference Barry2012). The attendees were asked to evaluate how the sponsorship of a specific event by a particular sponsor affects their awareness of the sponsor (cognitive level), their attitudes toward the sponsor (affective level), and their willingness to consider the sponsor’s product (conative level). This method facilitated a thorough assessment of sponsorship engagement across cognitive, affective, and conative dimensions.

These three dimensions align with Customer Engagement Theory, which emphasizes the importance of affective, cognitive, and behavioral engagement as indicators of brand-related relationship strength (Schönberner & Woratschek, Reference Schönberner and Woratschek2023). Additionally, SDT suggests that when spectators’ psychological needs for relatedness, competence, and autonomy are fulfilled during their interaction with sport content and sponsors, they are more likely to internalize sponsor messages and engage voluntarily (Bernhart et al., Reference Bernhart, Wilcox, McKeever, Ehlers and O’Neill2025). In digital environments, Parasocial Interaction Theory helps explain how fans develop perceived personal relationships with sponsors, athletes, or teams – despite the one-way nature of interaction – amplifying emotional investment and brand loyalty (Su, Guo, Wegner & Baker, Reference Su, Guo, Wegner and Baker2023).

Brand awareness is characterized as a mechanism that emphasizes the identification and cultivation of familiarity and recognition among a target audience regarding a specific brand (Foroudi, Jin, Gupta, Foroudi & Kitchen, Reference Foroudi, Jin, Gupta, Foroudi and Kitchen2018). Increased levels of awareness correlate positively with enhanced brand perception. Brand awareness increases the likelihood of consumer selection over brands with lower awareness (Foroudi et al., Reference Foroudi, Jin, Gupta, Foroudi and Kitchen2018). Koronios, Vrontis and Thrassou (Reference Koronios, Vrontis and Thrassou2021) define brand awareness as the degree to which a brand is recognized and remembered by consumers, indicating their familiarity with the brand. Brand recognition refers to the degree to which a consumer can identify a specific brand among a selection of brands within a specific group of goods.

The primary objective of sponsorship engagement is to foster a favorable consumer perception of a sponsor and/or its brand. Ajzen and Fishbein (Reference Ajzen and Fishbein1977) propose that an individual’s attitude toward engaging in a behavior is determined by their beliefs. This theoretical relationship between attitude and behavior has been further substantiated (Ajzen & Fishbein, Reference Ajzen and Fishbein1977). The theory of planned behavior posits that fostering a positive attitude toward an organization is crucial, as it directly affects consumer purchase intentions and, consequently, consumption behavior (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen2001). Previous research in sport sponsorship has focused on consumer attitudes toward corporate partners, their brands, events, and sponsorship as key areas of assessment (Koronios et al., Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2023).

From a sponsor’s perspective, consumer purchase intention serves as the most significant indicator of sponsorship effectiveness due to its influence on future sales (Crompton, Reference Crompton2004). The intent to purchase sponsors’ products serves as a key indicator for sports entities to validate their relationships with current sponsors and to negotiate future sponsorship agreements (Hong, Reference Hong2011). Meenaghan (Reference Meenaghan2013) posits that a fan’s response to sponsors progresses through several stages, beginning with awareness of the sponsors and culminating in the formation of purchase intentions and behaviors regarding their products. The awareness of sponsors among fans positively influences their attitudes toward the sponsors, which subsequently affects purchase intentions (Koronios et al., Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2024). Fans often purchase products from sponsors who support their team as a gesture of goodwill or to reciprocate the sponsor’s support for the team and/or event.

Model development

The current research introduces a novel framework that revolves around three key elements: (a) the antecedents of sport sponsorship (i.e., sport involvement, event attachment, subjective event knowledge, brand familiarity, sincerity of the sponsor, ubiquity of the sponsor, and sponsor-event congruence), (b) the mediator variable of consumers’ social media use, and (c) outcomes for the sponsor (i.e., engagement with sponsors). Based on the literature, the following model (Figure 1) and hypotheses are proposed.

Figure 1. The proposed model.

Methodology

This study primarily utilized the Strategic Sport Sponsorship Scale developed by Koronios et al. (Reference Koronios, Vrontis and Thrassou2021), with additional variables and items incorporated to assess social media usage, subjective event knowledge, and sponsors’ ubiquity. The research employed a questionnaire that retained six variables from the original scale – sport involvement, event attachment, brand familiarity, sincerity of the sponsor, sponsor-event congruence, and engagement with sponsors – and introduced three new variables: social media usage, subjective event knowledge, and sponsors’ ubiquity. The social media usage variable drew on Tang and Cooper’s (Reference Tang and Cooper2018) research, the subjective event knowledge was based on Moharana et al.’s (Reference Moharana, Roy and Saxena2023) study, and the ubiquity variable came from Petrovici, Shan, Gorton and Ford (Reference Petrovici, Shan, Gorton and Ford2014) findings. To validate the content of the three newly added variables, a panel of experts and a field test were utilized. The survey instrument was revised according to expert feedback, retaining items that were deemed valid by at least 75% of the experts. The questionnaire underwent a back-translation process from English to Greek, facilitated by a panel of experts. All responses were measured on a five-point Likert scale, which ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Sample and data collection

The current study used a quantitative technique to achieve its objectives. Questionnaires were collected from Greek spectators of the Paris 2024 Olympics. The data for this investigation were obtained using an online survey administered on the Limesurvey platform, with the support of a reputable website that actively promoted participation from the target audience. The study was completed only by spectators who confirmed having watched at least one hour of the Olympic Games. In this research, the concern of missing data did not arise, because it was a prerequisite to answer each question before accessing the next one. It is crucial to emphasize that the use of online data collection was chosen due to its cost-effectiveness and ability to gather a larger sample size over a wide geographical area (Newman, Bavik, Mount & Shao, Reference Newman, Bavik, Mount and Shao2020). Furthermore, it was hypothesized that those who engaged with social media platforms and used the Internet would exhibit a higher propensity to participate in an online survey. In order to ensure quality control, the researchers implemented measures to prevent duplicate entries, such as tracking IP addresses and monitoring time spent completing the survey. This study used a questionnaire collecting strategy that has resemblance to prior online research conducted by Koronios et al. (Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2022). A total of 7,412 questionnaires were successfully completed and analyzed using SPSS and AMOS.

Results

Construct validity of questionnaire

To assess the data’s readiness for analysis, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was employed, and sampling adequacy was verified via the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test. A Varimax rotation was conducted to evaluate the questionnaire’s factorial validity. The selection process for the factorial structure was based on the impact and significance of variables and eigenvalues, requiring that eigenvalues be greater than 1 and factor loadings exceed 0.6 (Tables 1 to 9). Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was then performed to confirm the reliability and validity of the variables. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to test the hypothesized relationships within the model. The adequacy and parsimony of the model were judged by various fit indices, including the chi-square statistic with degrees of freedom, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Normed Fit Index (NFI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), following the standards set by Kline (Reference Kline2023). The AMOS software was used for CFA and SEM analyses, while the SPSS software was employed for EFA tasks. A CFA was also performed to investigate the dimensionality of engagement with the social media usage scale, noting a significant correlation with sponsor engagement (r = 0.718). Preliminary exploratory data analysis, which included assessments of skewness, kurtosis, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, indicated that all variables deviated from normal distribution. Multivariate kurtosis, as indicated by Mardia’s coefficient, was recorded at 17.25 with a normalized estimate of 6.91. Given these findings and the data’s ordinal nature, the Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-square statistic was applied. This analysis confirmed a suitable fit for the five-parameter model, evidenced by χ 2 = 27.35, p < .01; NNFI = .980; CFI = .970; SRMR = .035; RMSEA = .070

Table 1. Exploratory factor analysis for sport involvement scale

Sample descriptive statistics

The total number of participants in the study was 9,415, with 42% (n = 3,954) identified as ‘heavy users’ of social media and 58% (n = 5,461) as ‘non-heavy users’ (Zhong, Huang & Liu, Reference Zhong, Huang and Liu2020). Within the ‘non-heavy user’ category, males accounted for 64.15% (n = 3,498) and females for 35.85% (n = 1,963). Among the ‘heavy users’, there were 66.25% male participants (n = 2,617) and 33.75% female participants (n = 1,337). The age distribution showed that the predominant age group among ‘non-heavy users’ was 26–35 years, representing 31.83% (n = 1,738) of that group, followed by those aged 46–55, who made up 35.16% (n = 1,920). Conversely, ‘heavy users’ presented a relatively even age distribution, with 37.65% (n = 1,489) in the 26–35 age bracket and 26.42% (n = 1,043) in the 46–55 age bracket. Regarding educational attainment, ‘non-heavy users’ featured a higher percentage of high school graduates at 24.61% (n = 1,344) compared to 20.94% (n = 828) among ‘heavy users’. However, ‘heavy users’ included a greater proportion of postgraduate degree holders at 46.13% (n = 1,823), while ‘non-heavy users’ had 41.75% (n = 2,280) with such qualifications. Marital status showed that 48.76% of ‘non-heavy users’ (n = 2,663) were married, compared to 45.28% of ‘heavy users’ (n = 1,791) who were married.

EFA and CFA results

CFA revealed that all scales were well-adapted, as presented in Tables 1 through 9. An EFA confirmed that the KMO index for most scales was above 0.85, reflecting excellent sampling adequacy. The explained variance by the factors varied between 72.5% and 86.8% for the nine scales. During the CFA, all scales displayed strong fit indices: Normed χ 2 values stayed below 2, RMSEA values were less than 0.08, and both NFI and CFI exceeded the benchmarks of 0.95 and 0.90, respectively. Moreover, the scales showed significant inter-correlations, with values ranging from 0.441 to 0.937, highlighting substantial interrelationships.

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis for event attachment use scale

Table 3. Exploratory factor analysis for subjective event knowledge scale

Table 4. Exploratory factor analysis for brand familiarity scale

Table 5. Exploratory factor analysis for sponsor sincerity scale

Table 6. Exploratory factor analysis for ubiquity of the sponsor scale

Table 7. Exploratory factor analysis for congruence scale

Table 8. Exploratory factor analysis for social media usage scale

Table 9. Exploratory factor analysis for engagement with sponsors scale

SEM results

A SEM analysis was performed to assess hypotheses H1–H14, as presented in Table 10. In the findings, ‘R’ denotes a rejected hypothesis, while ‘S’ indicates a supported one. The analysis yielded the following insights: Spectators’ sport involvement significantly impacts their engagement with sponsors, with a significant coefficient of b = 0.827 (p < .001), affirming hypothesis H1 (S). Spectators’ engagement with sponsors is positively influenced by their attachment to the event, with a coefficient of b = 0.568 (p < .005), endorsing hypothesis H2 (S). Spectators’ subjective knowledge about the event significantly correlates with their engagement with sponsors, evidenced by a coefficient of b = 0.795 (p < .001), supporting hypothesis H3 (S). Spectators’ familiarity with the sponsoring brand impacts their engagement with sponsors, marked by a significant coefficient of b = 0.441 (p < .005), backing hypothesis H4 (S). The sincerity of the sponsor significantly contributes to engagement with sponsors, with a coefficient of b = 0.629 (p < .001), confirming hypothesis H5 (S). The anticipated ubiquity of the sponsor significantly drives spectators’ engagement with sponsors, shown by a coefficient of b = 0.572 (p < .005), validating hypothesis H6 (S). The anticipated congruence between sponsors and the event significantly affects spectators’ engagement with sponsors, with a coefficient of b = 0.898 (p < .001), supporting hypothesis H7 (S).

Table 10. Final (best) SEM model

S = Supported, R = Rejected, SE = Standard Error, NNFI = .980; CFI = .970; SRMR = .035; RMSEA = .070.

Moreover, social media usage serves as a mediator in the effect of various factors on spectators’ engagement with sponsors. The level of spectators’ involvement in sports, when mediated by their use of social media, significantly impacts their engagement with sponsors, evidenced by a coefficient of b = 0.931 (p < .001), supporting hypothesis H8 (S). The extent of spectators’ attachment to the event, mediated by their social media usage, considerably influences their engagement with sponsors, as shown by a coefficient of b = 0.759 (p < .001), backing hypothesis H9 (S). Spectators’ subjective understanding of the event, mediated by their use of social media, significantly impacts their engagement with sponsors, with a coefficient of b = 0.837 (p < .001), affirming hypothesis H10 (S). Spectators’ awareness of the sponsoring brand, mediated by social media usage, significantly affects their engagement with sponsors, supported by a coefficient of b = 0.627 (p < .001), confirming hypothesis H11 (S). The perceived sincerity of the sponsor, when mediated by the spectators’ social media usage, significantly enhances their engagement with sponsors, with a coefficient of b = 0.631 (p < .001), validating hypothesis H12 (S). The anticipated ubiquity of the sponsor, mediated by spectators’ use of social media, considerably affects their engagement with sponsors, supported by a coefficient of b = 0.859 (p < .001), supporting hypothesis H13 (S). The expected congruence between the sponsor and the event, mediated by the spectators’ social media usage, significantly impacts their engagement with sponsors, indicated by a coefficient of b = 0.937 (p < .001), endorsing hypothesis H14 (S). These results highlight that engagement with sponsors is influenced not just directly by specific factors but also through intermediaries like social media usage, underscoring the growing impact of digital platforms on shaping consumer behavior in sports sponsorships.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to ascertain the impact of sponsorship on the Olympics spectators’ engagement with sponsors, as well as to ascertain if spectators’ social media consumption mediates such a relationship. Before exploring the findings in depth, it is crucial to highlight the importance of this endeavor in connecting sport sponsorship with spectators’ social media consumption. This study indicates that audiences have adopted and incorporated the ‘social platform’ into their consumption of sport mega-events. This is evidenced by their engagement with popular social media sites (e.g., Facebook, YouTube), posting about the Olympics, and actively interacting with sponsors. The research indicates that the integration of social media platforms influences spectators’ engagement with sponsors, highlighting a significant relationship between social media usage and sponsorship outcomes. The research identified several factors that significantly predicted spectators’ engagement with sponsors during the Paris 2024 Games. Spectators’ engagement with sports, their attachment to the Olympics, subjective knowledge of the event, familiarity with sponsoring brands, perceived sincerity and ubiquity of sponsors, and the congruence between sponsors and the event significantly influenced spectators’ awareness, attitudes, and purchase intentions regarding sponsors’ goods and services.

The research indicates that Olympics viewing on social media was assessed based on media use routines, including the duration of time spent watching sports news and events across television, online platforms, and mobile devices. Viewers of the Social Olympics were individuals already familiar with digital platforms for consuming sports and general media content. The findings demonstrate that audiences intentionally utilized social media to obtain information, engage with family and friends, foster a sense of connection, and experience social interaction during the Paris 2024 Games. The results indicate that social media significantly influences the structural constraints associated with traditional sports production and distribution, particularly in relation to sponsorship outcomes. Beyond confirming the strength of these pathways, this study introduces a significant theoretical advancement by positioning social media usage as a mediating construct in the sponsorship process. This finding redefines the role of digital platforms within sponsorship theory – not merely as channels of activation, but as structural amplifiers that shape how antecedents (such as sport involvement and sponsor-event congruence) convert into engagement outcomes. Prior frameworks (e.g., Cornwell & Kwon, Reference Cornwell and Kwon2019; Meenaghan, Reference Meenaghan2013) conceptualized activation as a post-sponsorship task; our model extends these by showing that digital engagement behaviors interact with and magnify sponsorship inputs during the sponsorship experience itself.

Moreover, while our empirical setting focuses on the Olympic Games, the constructs within the model – social media usage, sponsor sincerity, and brand familiarity – are applicable across different levels of sport. Thus, this framework offers a generalizable lens for league or team sponsorships, particularly where social media is actively leveraged throughout the season to sustain engagement. Brands can employ similar diagnostic models to evaluate how digital behaviors mediate between sponsorship strategies and consumer outcomes in varied sponsorship contexts, offering both tactical and strategic insights for sustained brand–consumer relationships. Sports organizations and practitioners should utilize social networking sites not only as platforms for information distribution and cross-promotion (Tang & Cooper, Reference Tang and Cooper2017) but also to enhance the effectiveness of sponsorship agreements.

This study provides several significant advances in theory and methodology. This involves creating and verifying a suitable conceptual framework that accurately captures the essential elements of the sponsorship package. The suggested solution offers sport managers and company executives detailed diagnostics at the item level, which may enhance their daily sponsorship plans and tactics. An important contribution of this research is its ability to establish a connection between a metric of sport sponsorship and spectators’ social media usage. In conclusion, research demonstrates that sport sponsorship is widely recognized as having a significant influence on spectators’ engagement with sponsors. This discovery offers a helpful perspective on how executives perceive the efficacy of sponsorship efforts as a significant and sustainable goal. Furthermore, this research is the inaugural investigation of such a correlation within the context of sport mega-events, such as the Olympics. The study results provide valuable and perceptive contributions to the limited body of literature on the significance of spectators’ social media usage and its effect on their awareness of, attitudes toward, and purchase behavior regarding sponsors’ goods and services.

Theoretical implications

The field of academic research on behavioral patterns in sport sponsorship has evolved rapidly (Koronios et al., Reference Koronios, Vrontis and Thrassou2021) and has seen significant growth over the past decade (e.g., Koronios et al., Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2022). There remains an opportunity to further academic discussions on sponsorship and social media. This study contributes significantly to the literature on sports sponsorship, social media, and spectator engagement, addressing the limited existing research on the effectiveness of social media communications in this context (Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, Soni and Kishore2020). Given the evolving nature of sport sponsorship, it is crucial to clarify misconceptions regarding the actual impact of factors like spectators’ social media engagement during major sporting events, including the Olympics.

This research enhances our understanding by investigating the mediating effect of social media use on the relationship between seven antecedent factors and spectator engagement with sponsors. This study integrates the degree of spectators’ social media use as a mediator, providing a nuanced perspective on how digital platforms can enhance or modify the influence of factors such as sport involvement, event attachment, subjective event knowledge, brand familiarity, sponsor sincerity, sponsor ubiquity, and sponsor-event congruence. The incorporation of social media metrics offers a modern perspective for evaluating sponsorship engagement dynamics, moving beyond conventional methods to highlight the essential influence of digital interaction on sponsor relationships.

This research explores the essential influence of spectators’ social media usage on their engagement with sponsoring firms, building on the need to investigate the precursors of such engagement (Kumar & Kumar, Reference Kumar and Kumar2019). This study examines the mediating role of social media usage in the context of sponsorship. Previous research has established both direct and indirect (Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, Soni and Kishore2020) relationships between social media usage and behavioral outcomes. The findings indicate that social media usage acts as a significant mediator among seven antecedent factors – sport involvement, event attachment, subjective event knowledge, brand familiarity, sponsor sincerity, sponsor ubiquity, and sponsor-event congruence – and consumer engagement with sponsors. This mediation highlights the role of social media usage in influencing and shaping the impact of these factors on consumer engagement with sponsoring firms. The mediating role of social media usage is strongly supported by multiple theoretical frameworks in media, marketing, and sponsorship literature. Sponsorship Theory traditionally explains consumer responses as a function of sponsor–event fit and exposure; this study expands that view by demonstrating that social media serves as an active, mediating mechanism that shapes how antecedents like brand familiarity, event attachment, and sincerity influence awareness, attitudes, and behavioral engagement (Koronios et al., Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2023). From a UGT perspective, spectators utilize social platforms to fulfill psychological and social needs – such as entertainment, identity expression, and social interaction – which in turn guide how they interpret and engage with sponsorship content (Osokin, Reference Osokin2019). Relationship Marketing theory further contextualizes this process by highlighting how digital engagement fosters sustained brand–consumer relationships based on trust, emotional resonance, and loyalty (Abeza et al., Reference Abeza, O’Reilly and Reid2013). Moreover, spectators often engage in parasocial interactions with athletes, teams, and even sponsor brands through social media, forming one-sided yet psychologically meaningful connections that enhance sponsor salience. Finally, the study aligns with Engagement Theory, which emphasizes interactivity, emotional investment, and co-creation as pathways to deeper consumer involvement (Schönberner & Woratschek, Reference Schönberner and Woratschek2023). By synthesizing these frameworks, the research positions social media not merely as a promotional channel but as a psychologically and strategically embedded layer within the sponsorship ecosystem. This study analyses the mediation role, offering a nuanced understanding of how digital interactions can strategically influence consumer relationships with sponsors, highlighting the intricate interdependencies within digital sponsorship ecosystems.

Practical implications

Social media communications significantly influence contemporary marketing practices. The emergence of Web 2.0 has led to digitization impacting the roles of various stakeholders within the sporting ecosystem, such as fans, league marketers, players, broadcasters, sponsors, and governing authorities. Social media communications significantly influence sports sponsorship and spectator engagement with sponsors. This insight is crucial for professionals in sports marketing. The sport sponsorship market has demonstrated growth and suggests potential for further expansion (Naraine et al., Reference Naraine, Bakhsh and Wanless2022). The study’s findings offer valuable insights and guidelines for event marketers and managers in developing strategies that strengthen spectators’ attachment to the event, potentially resulting in increased engagement with sponsors.

Based on the understanding of subjective knowledge as defined in existing literature, it is crucial for event managers to actively focus on enhancing spectators’ subjective knowledge about the event. According to the findings, this plays a critical role in shaping consumer behavior and decision-making processes. Therefore, by fostering deeper, more accurate subjective knowledge, event managers can significantly boost spectators’ engagement with sponsors, enriching the overall experience and effectiveness of sponsorships. This strategic focus not only enhances the perceived value of the event but also strengthens sponsor relationships with consumers, leading to more successful event outcomes.

Our findings from the moderation analysis offer important insights for event and sponsor brand managers in designing sponsorship communications and targeting potential consumers. Social media usage notably improves spectators’ engagement with sponsors by positively mediating the relationships between the identified antecedent factors and the proposed dependent variable, engagement with sponsors. In contemporary society, fans utilize online communities of leagues to assert their presence among peers. Marketers can capitalize on this by identifying innovative strategies to enhance engagement. This can be accomplished through online competitions, the development of games on social media platforms, soliciting posts and videos from fans, and enhancing content to expand audience reach. Competitions may result in fans receiving rewards such as stadium tickets and opportunities to meet their favorite players. This engagement is significant as the study has demonstrated a stronger indirect relationship between spectators’ social media usage and their engagement with sponsors.

Limitations and further research

This study contributes theoretically to the existing body of knowledge in sport sponsorship literature and provides important management insights. This study presents several specific limitations that warrant acknowledgement. This study offers significant insights into the utilization of social media for sport mega-events; however, the results must be interpreted contextually and with caution. The cross-sectional design of this research precludes any claims of causal inferences. This study utilized self-reported behavior data collected through a nonprobability online survey targeting viewers of the 2024 Paris Olympics in Greece. The respondents, recruited through a prominent sports website, exhibited a bias toward younger demographics with comparatively higher education levels (Tang & Cooper, Reference Tang and Cooper2017), which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader population. A promising avenue for future research involves analyzing the proposed conceptual framework within a sponsorship agreement in a particular sport, such as basketball, and juxtaposing the results with existing data.

The results may have been affected by the limited duration of the sponsorship arrangement, which coincided with the Olympics. Previous research indicates that the duration of a sponsorship significantly affects its effectiveness, producing either positive or negative outcomes (Koronios et al., Reference Koronios, Ntasis and Dimitropoulos2023). Therefore, examining the effects over an extended duration would be beneficial.

A further limitation relates to the methodological techniques employed in this study. Despite the implementation of measures to reduce the impact of the demand effect and social desirability bias, various variables may continue to influence the reliability of the results reported in this research. Tan and Papasolomou (Reference Tan and Papasolomou2023) indicate that social desirability bias can influence the accuracy of surveys employing multiple items to assess a specific construct. Furthermore, survey respondents frequently provide politically favorable answers, resulting in dubious associations and relationships among variables (Koronios & Dimitropoulos, Reference Koronios and Dimitropoulos2020). The design of the questionnaire, its self-administration, and the correlational nature of the data in this study may have influenced the outcomes. Moreover, participants’ exposure to the sponsor’s advertisements, labels, and trademarks may influence the research findings. This offers a valuable opportunity for further investigation focused on assessing the impact of this specific bias in sponsored research. A further limitation pertains to the cultural specificity of the dataset. This study draws exclusively from Greek spectators of the Paris 2024 Olympics, which may limit the generalizability of the findings across broader international contexts. Since sponsorship perceptions, digital behaviors, and brand engagement often vary by country and cultural norms, cross-national or comparative studies could uncover important differences in sponsorship dynamics.

A further limitation pertains to the cultural specificity of the dataset. This study draws exclusively from Greek spectators of the Paris 2024 Olympics, which may limit the generalizability of the findings across broader international contexts. Since sponsorship perceptions, digital behaviors, and brand engagement often vary by country and cultural norms, cross-national or comparative studies could uncover important differences in sponsorship dynamics. Additionally, while the current research applies robust cross-sectional methods, future studies could benefit from adopting a longitudinal design to track evolving engagement over time or an experimental approach to isolate the causal effects of specific sponsorship stimuli. These methods would strengthen theoretical contributions and provide further validation of the mediating role of social media. The findings of this research may significantly assist future scholars in the area of sport sponsorship in addressing these biases when analyzing fan engagement patterns.