Anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery, also known as Bland–White–Garland syndrome, constitutes 0.5% of CHDs.Reference Wolf, Vercruysse and SuysWolf1 The treatment of this anomaly is establishing a dual coronary artery system with either surgical reimplantation of the left coronary artery into the left sinus valsalva or creation of an intrapulmonary artery baffle (Takeuchi procedure).Reference Turley, Szarnicki and Flachsbart2,Reference Takeuchi, Imamura and Katsumoto3 This newly created coronary artery system is prone to stenosis or total occlusion after surgery. These complications lead to significant myocardial ischaemia, infarction, and heart failure. Recently, transcatheter intervention options are now being considered due to the high risk of reoperation. But expected somatic growth and concern about the long-term outcome of stents limit their use in the children.

Herein, we present the procedural technique in an infant with anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery who had coronary stent implantation to relieve post-surgical left main coronary artery obstruction.

Case

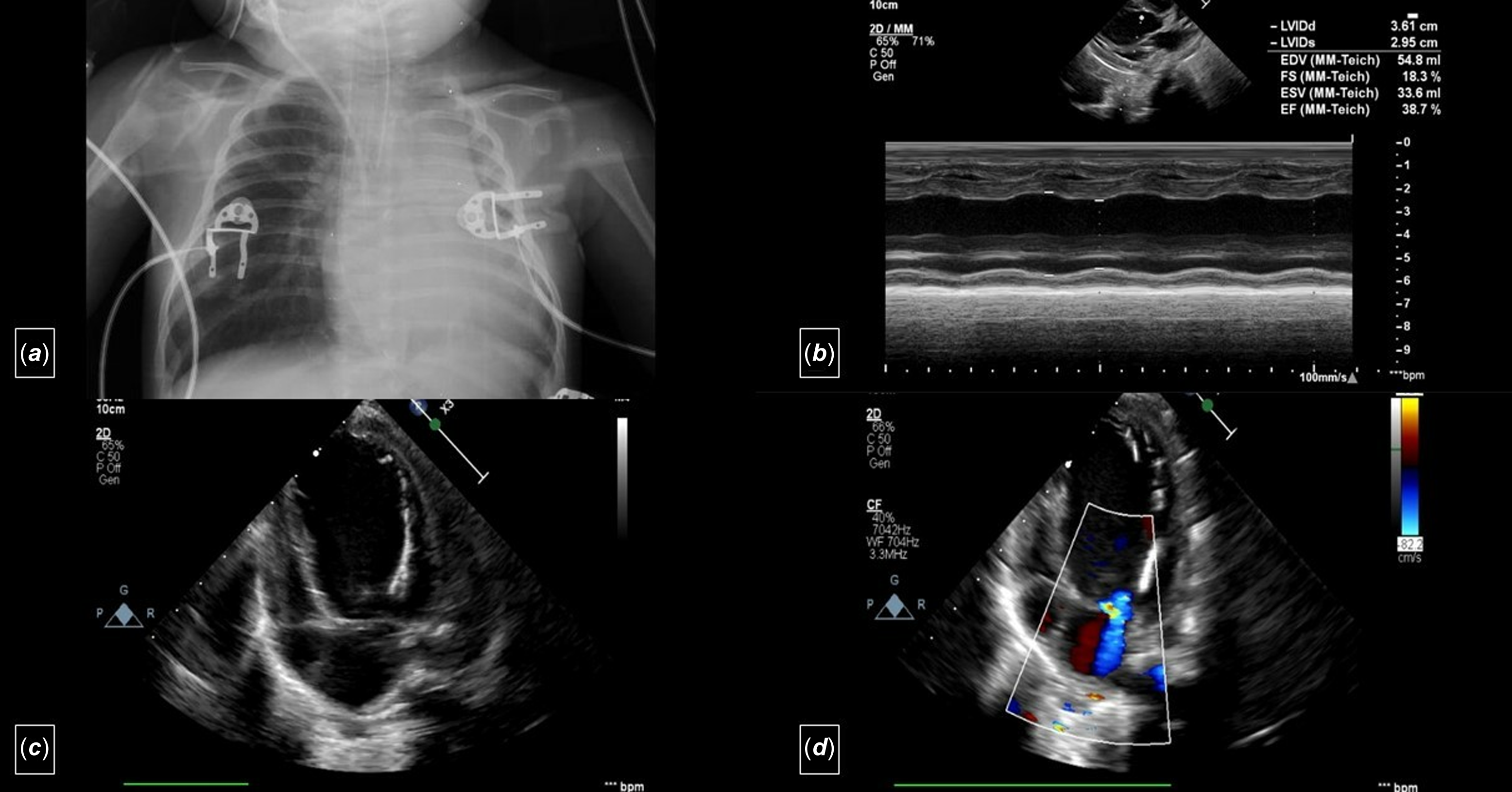

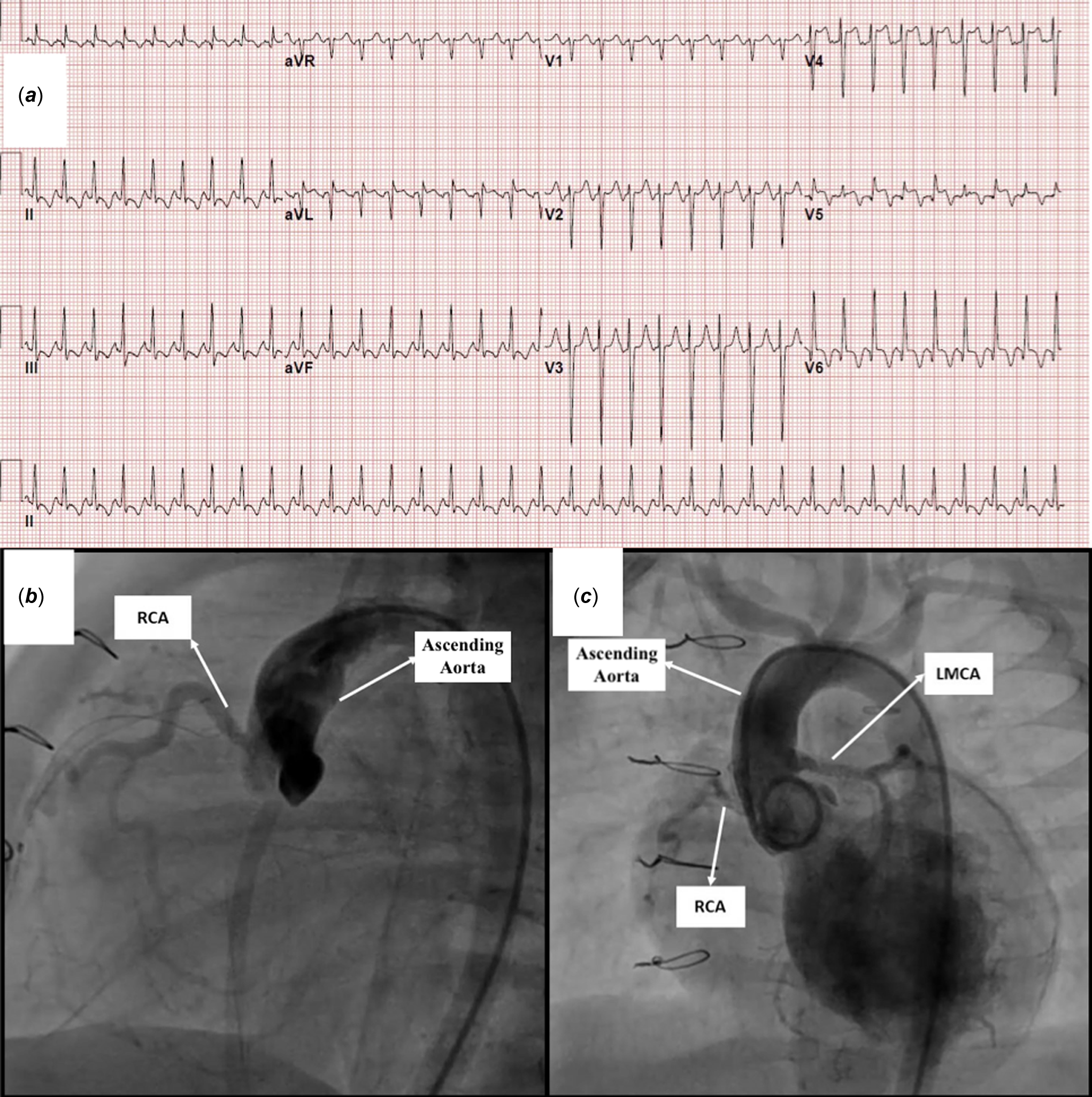

A two-month-old, 4.5 kg weight girl diagnosed with anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery and severe congestive heart failure was referred for surgery. Echocardiography revealed dilation of the left ventricle, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction ( 38%), a moderate degree of mitral regurgitation, and endocardial fibroelastosis (grade 2) (Figure 1). The electrocardiography showed pathological Q waves in the lateral lead (notable in aVL) (Figure 2a). Cardiac catheterisation demonstrated the anomalous origin of the left coronary artery.

Figure 1. a. Telecardiography shows cardiomegaly. b: M-mode echocardiography (transthoracic echocardiogram) from a parasternal long-axis view showing dilatation of the left ventricle and decreased cardiac function. c: Apical four-chamber view (transthoracic echocardiogram) showing dilatation of the left ventricle and endocardial fibroelastosis (grade 2). d: Apical four-chamber view (transthoracic echocardiogram) showing the moderate degree of mitral regurgitation.

Figure 2. a. Electrocardiography showing pathological deep Q waves in the lateral lead (notable in aVL). b: Aortic root angiogram demonstrated almost total occlusion of the left main coronary artery ostium at the anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery reimplantation site and retrograde filling from the right coronary artery. c: Post-intervention angiography showed reestablished flow to both the circumflex and the left anterior descending artery arteries.

The patient underwent left main coronary artery reimplantation in the ascending aorta above the sinotubular junction. Antegrade filling of the coronary arteries was observed in the echocardiography within the first 14 postoperative days. She was haemodynamically stable during this period. Whenever the patient was tried to be weaned from the mechanical ventilator, her haemodynamics deteriorated. At that time, echocardiography showed that the left main coronary artery was filled with the retrograde flow. Also, newly emerged ST-T changes were observed in the electrocardiography. In addition, serum troponin levels, which regressed to near normal on the 13th postoperative day, started to rise again on the 15th postoperative day.

On the postoperative 23rd day, diagnostic cardiac catheterisation was performed. Aortic root angiogram demonstrated almost total occlusion of the left main coronary artery ostium and retrograde filling from the right coronary artery (Figure 2b, Supplementary Video 1). The AR1 catheter (Cordis Europe, Johnson & Johnson Medical N.V., USA) was advanced retrogradely through the descending aorta with the help of 0.035 hydrophilic guidewire and placed into the coronary ostium. A 0.014” intermediate support straight tip guidewire was then used to cross the lesion and advanced into the left anterior descending artery (Supplementary Video 1). The 4 Fr femoral artery sheath was exchanged for a 4/5 Fr Glidesheath Slender introducer (Terumo Medical Corporation, NJ, USA), and 5F Cordis Vista Brite Tip JR 4 guiding catheter (Cordis Europe, Johnson&Johnson Medical N.V., USA) was advanced over the guidewire up to the left main coronary artery ostium. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty was performed using a The Mini Trek RX 1.5x12 mm non-compliant balloon. The procedure was repeated using a Simpass Plus 2 x 12 mm balloon(Supplementary Video 1). Coronary angiography revealed successful recanalisation despite ongoing mild stenosis in the proximal left main coronary artery (Supplementary Video 1). Stent implantation was decided to relieve stenosis constantly because of the high mortality and morbidity related to the repeated surgical procedure. Another 0.014” extra support coronary guidewire was placed into the distal the left anterior descending artery. The Alvimedica Commander 2.5x9 mm bare-metal stent was deployed in the left main coronary artery proximal to its bifurcation (Supplementary Video 1). Post-intervention angiography showed reestablished flow to the circumflex and the left anterior descending artery (Figure 2c, Supplementary Video 1). Heparin infusion (20 IU/kg/h) was administered for 24 hours. Thromboprophylaxis was initiated with aspirin (5 mg/kg/day) and clopidogrel (1 mg/ kg/day) on the next day.

Left ventricular ejection fraction increased to 44% on echocardiography performed six weeks after stent implantation. Cardiac catheterisation performed two months after stent implantation showed no in-stent or coronary restenosis. The patient was discharged on day 52 after stent implantation. After six months of follow-up, ejection fraction was increased to 55% in echocardiography, and no ischaemia findings were observed in the electrocardiography. The patient is now 3 years old and weighs 13 kg, and her cardiac functions are normal.

Discussion

The definitive treatment of this anomaly is creating two separate coronary vascular systems filling antegradely from the aorta. The direct reimplantation method is the treatment of choice with low complication and mortality rates and favourable good long-term results. Reference Lange, Vogt and Hörer4 In the postoperative period, partial or total occlusions rarely may occur, especially in the anastomosis region. However, the high risk of reoperation led to the idea of implanting a stent in the left main coronary artery. With these, the data about percutaneous coronary stent angioplasty in infants are limited in the current literature. Limitations of this procedure include vascular complications, technical challenges, acute thrombotic stent occlusion, restenosis, and unknown long-term follow-up results. Reference Lezo, Pan and Herrerade5,Reference Bratincsák, Salkini and El-Said6 In this case report, we aimed to share our experience of dealing with restenosis after anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery repair.

Vascular complications are the main possible concerns about the mid-term results of the procedure. Reference Odemis, Haydin and Guzeltas7 For this reason, to prevent permanent arterial damage, we elaborate to use the smallest diameter introducer sheaths. Similar to our case, Gender et al. reported that performing percutaneous interventions in small children using the GlideSheath Slender is safe and effective. Reference Gendera, Eicken and Ewert8 It allows the reduction of outer sheath diameter by one French, which creates a major difference in this patient group.

Another problem is restenosis due to neointimal proliferation within the stent. Bratincsák et al. reported that a stent diameter of more than 2.5 mm seems to be associated with a significantly longer short- to mid-term survival free from reintervention as preferred in our case. Reference Bratincsák, Salkini and El-Said6 During the long-term follow-up, if there is no narrowing within the 2.5 mm stent in the left main coronary artery, the left main coronary artery z score will still be around zero when the patient is about 30 kg. Reference Dallaire and Dahdah9 This estimate suggests that it may give us a chance that the coronary artery can be followed for about ten years without intervention.

The optimal prophylaxis for the prevention of stent thrombosis in infants is not known. Dual antiplatelet agent therapy (aspirin and a platelet P2Y12 receptor blocker) seems the most reasonable strategy. Reference Brilakis, Patel and Banerjee10 Nearly all reported patients were treated, at least initially, with a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel. Reference Bratincsák, Salkini and El-Said6 In light of the literature, we elected to treat our patient with dual antiplatelet therapy.

Conclusion

The definitive and permanent treatment for anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery disease is surgical correction. Percutaneous coronary intervention is a feasible option in infants who develop coronary artery obstruction after surgical reimplantation for anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery if the risk of reoperation was believed to be unacceptably high. This option is a temporary solution that can save the patient time before the second surgery.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951124026544.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in this case were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1975 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents.