The 2015 Paris Agreement aims to hold the increase in global average temperature to below 1.5–2° C relative to pre-industrial levels through national pledges to voluntarily reduce carbon emissions. As of 2021, 181 of 195 signatory states have submitted “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Early assessments of NDCs document substantial cross-country heterogeneity in the ambition and relative burden-sharing of mitigation commitments;Footnote 1 however, few studies attempt to explain this variation.Footnote 2 We explore leaders’ incentives to set climate commitments and subsequently make costly efforts toward implementing those commitments.

Leaders’ decisions to make climate commitments and ultimately see them through are undoubtedly complex. Consider the NDC of the United Kingdom, which in December 2020 committed the country to reducing economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions by at least 68 percent by 2030, compared to 1990 levels.Footnote 3 This commitment was made by then–Prime Minister and member of the Conservative Party Boris Johnson, who claimed that “the UK will be home to pioneering businesses, new technologies and green innovation as we make progress to net zero emissions, laying the foundations for decades of economic growth in a way that creates thousands of jobs.”Footnote 4 Indeed, Johnson’s ambition was a watershed moment for the world, as the UK became the first major economy to pass a net zero emissions law.Footnote 5

However, less than three years later, incumbent Tory Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced he would push back the cutoff for selling new petrol and diesel cars and the phasing-out of gas boilers, key policy considerations in meeting the net zero target.Footnote 6 Sunak’s rollback was scrutinized as an attempt to relieve voters of anticipated costs of the green transition in the run-up to the country’s next election. The Labour Party was perceived as the greener party, and liable to implement the costly policies to which the Conservatives had initially committed the country.Footnote 7 Sunak had hoped to position the Conservatives to consumers as a cheaper, albeit less green, alternative to a potential Labour government. Of course, in the July 2024 election, issues other than climate change dominated the electoral landscape; the Conservatives’ ability to make the issue salient on the margin proved insufficient, and Labour won despite the perceived costliness of its carbon reduction policies.

We present a formal model probing the domestic motivations behind the setting of climate targets. Two parties, Green and Brown, compete for political office. They vary in their marginal costs of implementing mitigation policy: the Green party faces lower costs than the Brown party and is willing to commit to more expansive climate reforms ex ante. As the incumbent, one of these parties sets a national climate commitment; the party that wins the election then determines whether they want to implement domestic policy to meet that target. Voters support either the Green or the Brown party given the downstream mitigation measures induced by the nation’s pledge. At the end of the game, nations imperfectly observe each leader’s mitigation efforts and assess whether targets were met in a “global stocktake”; leaders deemed to have underdelivered relative to their national commitments are “shamed.”

Our model is consistent with three central features of the Paris Agreement’s structure. First is the notion that Paris seeks to recenter domestic politics in the implementation of international climate goals.Footnote 8 Leaders choose their own commitments rather than accepting the terms of legally binding reduction targets, as with the Kyoto Protocol,Footnote 9 which makes understanding the domestic political considerations surrounding the setting of commitments paramount. Second is the idea that leaders first determine NDCs and then must enact policies designed to fulfill that commitment. In the model, the incumbent party sets a commitment and then costly effort into mitigation strategies to meet the target is exerted in the future. Third is that these goals are not enforced formally; climate laggards incur only reputational costs, known as “naming and shaming,” for failing to meet their targets.Footnote 10 We consider how the domestic electoral competition between political parties entices leaders to set different commitments in the shadow of possible international shaming.

Our analysis uncovers two relevant mechanisms through which domestic politics affect climate commitments. First, leaders may tie the hands of the opposition party and pick commitments to bring downstream policy measures closer to their preferred outcomes. Even apart from electoral considerations, leaders may care about implementing climate goals on pure policy grounds. Leaders have policy preferences over possible levels of effort and can tailor their pledges to ensure that their preferred policies are implemented in the future. In particular, when elections are relatively insensitive to climate policy, the Green party can tie the hands of the Brown party after the election with an ambitious target. That is, the Green party can design their pledge in order to force the Brown party to enact policy closer to the Green party’s policy preference.

A second set of incentives relates to the value of office-holding. If winning elections is leaders’ dominant consideration, then they set commitments in order to maximize their electoral prospects based on the anticipated costs to voters of downstream mitigation measures. The Green party faces an electoral disadvantage relative to the Brown party in this regard because the Green party would ex ante prefer a more ambitious mitigation strategy than the median voter. The Brown party can leverage this advantage by counterintuitively embracing a lofty climate commitment. If the cost of being shamed is high enough, the Green party will try to fulfill more ambitious pledges, while the Brown party will not. The Brown party chooses an ambitious target, knowing it would not comply and would be shamed. However, the Green party would be willing to make costly mitigation efforts to meet the goal, and this makes the Green party electorally unattractive to the median voter. Interestingly, while the commitment itself is uniform across national parties, voters’ expectations about each party’s likelihood of meeting it are different, which generates electoral incentives for anti-environmental parties to exploit Paris’s structure.Footnote 11 Ambitious climate commitments can therefore be leveraged to maximize electoral prospects based on how those commitments chart future national implementation measures and their subsequent costliness for voters.

By unpacking these mechanisms, our theoretical analysis explains how variation in observed climate commitments and subsequent policy outcomes arises. Given the Paris Agreement’s structure, one country’s commitment has no direct effect on the commitments of other countries. There is no reciprocity baked into the agreement’s terms. Moreover, there is no international infrastructure to render these pledges “credible.” Hence, heterogeneity in pledges, and in efforts to implement these pledges, is driven by variation in politics within nations. Our model points to changes in domestic fundamentals—like variation in the median voter’s willingness to pay for climate policies, public support for climate policy as an electoral issue, parties’ valuation of holding office, and parties’ valuations of climate policy, among other parameters—which point to different incentives that may drive leaders to implement more or less ambitious climate commitments. It is these domestic forces that also ultimately guide the extent to which leaders see these commitments through.

We contribute broadly to the literature on the domestic and international political economy of climate agreements. Much of the recent work in climate politics focuses on public opinion.Footnote 12 Experimental work consistently finds that support for climate policy among both citizens and politicians is highly contingent on the expected costs.Footnote 13 Scholars have sought to identify consumers’ willingness to pay for particular climate policiesFootnote 14 and whether there exist broad “climate coalitions” in favor of climate-friendly policies.Footnote 15 We complement this work in two ways. First, we provide a theoretical rationale for leaders’ politically optimal climate policies in the shadow of domestic support, which helps explain the intensity of mitigation policy that should be expected in equilibrium. Second, we demonstrate how leaders internalize voters’ anticipated costs of implementing climate policy in setting their NDCs ex ante and how these costs may be leveraged for electoral gain.

Theoretically, our model fits squarely within the “two-level games” tradition of modeling international cooperation.Footnote 16 We characterize the effects of elections on the incentives to commit to international treaties.Footnote 17 Battaglini and Harstad demonstrate leaders’ electoral incentives to sign “weak treaties” in which leaders overcommit but may underdeliver on their environmental promises.Footnote 18 Köke and Lange also consider the ratification of international environmental agreements from a domestic perspective and investigate the role of uncertain ratification on the depth of commitments.Footnote 19 Dai also finds that governments exhibit greater compliance with international treaties when pro-compliance domestic groups have more electoral leverage and informational capacity, using the case of the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution.Footnote 20 Also, as is common in two-level games, we highlight how the preferences of domestic actors may serve as an endogenous veto constraint on the ability to implement international commitments,Footnote 21 here reflected in the voters’ willingness to pay for mitigation measures.

Previous approaches to modeling the Paris Agreement have interrogated the effects of its novel institutional features on the prospects for climate cooperation. For example, Harstad presents a dynamic bargaining model that documents the conditions under which the Paris Agreement yields more ambitious climate commitments than the Kyoto Protocol.Footnote 22 Other models capture how Paris’s role in disseminating information affects the scope for ambitious contributions.Footnote 23 While we are not the first to try a formal model of climate change cooperation, ours is the first to provide a domestically microfounded story of the implementation of the Paris Agreement that goes beyond global collective-action concerns.Footnote 24

The Paris Climate Accord has no inherent means of sanctioning noncompliance, and, as we shall see, reputational costs will play a sizable role in determining equilibrium commitments. We therefore contribute to the literature interrogating the efficacy of naming and shaming.Footnote 25 Problems like information transmissionFootnote 26 or issue politicizationFootnote 27 may stymie naming and shaming and thus weaken compliance, while strategies such as issue linkageFootnote 28 may enhance reputational incentives to comply. Despite potential shortcomings, recent studies of policy elites demonstrate that policymakers view naming and shaming as an adequate, and even preferable to other means of sustaining cooperation.Footnote 29

How naming and shaming “works” is central to cooperation under Paris and therefore highly relevant in our study. While we follow the human rights literature and think about shaming coming from international actors in a reduced-form way,Footnote 30 empirical studies have also sought to tease out domestic microfoundations for compliance. Tingley and Tomz find that shaming by other countries increases support for climate commitments.Footnote 31 Other experimental work also demonstrates the presence of shaming costs for leaders who fail to live up to their promises.Footnote 32

Finally, we complement a burgeoning empirical literature on the effects of the Paris Agreement and the determinants of NDCs. Tørstad and Wiborg use a conjoint experiment to demonstrate that the likelihood of compliance is a strong determinant of general public support for climate agreements.Footnote 33 In general, empirical evidence suggests that the quality of national political institutions explains most variability in “credible” climate commitments.Footnote 34 Wealthier countries pledge to undertake greater emission reductions with higher costs,Footnote 35 and more democratic countries and countries more vulnerable to climate change have been associated with more ambitious commitments.Footnote 36 However, given the complexity in setting policy to meet mitigation targets, some scholars have argued that it is difficult to know whether Paris targets are empirically comparable between countries.Footnote 37 Hence we provide a theoretical treatment of NDCs and the domestic political forces that shape them.

Paris and Climate Commitments

The Paris Agreement seeks to overcome the global collective-action problem by encouraging voluntary emissions-reduction commitments enforced through reputational sanctions. Article 4.2 of the Agreement requires that “each Party shall prepare, communicate and maintain successive nationally determined contributions that it intends to achieve.”Footnote 38 Rather than delegate authority to an international body that imposes top-down, legally binding targets as in other international climate governance frameworks like the Kyoto Protocol, nations asymmetrically consider their own incentives and abilities to abate.Footnote 39 As negotiated, such an institutional design is maximally “flexible,”Footnote 40 albeit very “shallow.”Footnote 41 Taking these institutional attributes as exogenous, we consider the domestic political incentives to make commitments within such an agreement. Importantly for our story, these initial commitments serve as endogenous reference points: climate pledges, while chosen strategically, may redefine the scope of desirable policies that leaders implement in the future.Footnote 42

The Paris Agreement does not explicitly identify any enforcement mechanism to ensure that NDCs are implemented. Article 7.14 establishes the system of pledge-and-review in which nations reconvene for a “global stocktake” to assess progress toward NDCs and inform future measures.Footnote 43 Articles 13, 14, and 15 outline the “enhanced transparency framework” and information-dissemination process intended to serve as compliance mechanisms. The first global stocktake occurred in 2023, and they are set to be held every five years thereafter. As part of the process, countries submit reports on their performance (a noisy signal of their effort to meet their pledges). The stocktake itself does not serve to “name and shame” individual countries,Footnote 44 but it does generate a report laying the groundwork for assessments of policy goals by other nations and public actors like NGOs and activists, to pressure leaders into adopting more ambitious commitments.Footnote 45 This process thus provides a platform to facilitate international shaming, deemed effective by policymaking elites.Footnote 46

Given the long time horizon between submission of NDCs and subsequent evaluations of progress, enforcement of the agreement is informal, and if costs of noncompliance are incurred they are levied in the future, not when nations initially set their targets. Leaders who set their nation’s commitments need not be in power when it comes time to “name and shame” those who did not follow through on their commitments.

Since pledges are not legally binding and enforcement is uncertain, leaders vary in their ultimate willingness to comply with their nation’s target. We stipulate that leaders pay a “shaming cost” if judged to have failed to fulfill their commitment. This cost is larger if leaders anticipate greater reputational sanction for breaching their commitment, and larger expectations of shaming costs can entice leaders to fulfill larger commitments. However, in a world with imperfect monitoring,Footnote 47 the precision with which the international community can verify national emissions reductions also affects leaders’ incentives to comply with the target. As we will demonstrate, downstream mitigation efforts are dependent on the interaction between these international factors and domestic policy preferences.

Model Setup

We model a multistage policy process in which nations gather at a multilateral summit to pledge emissions reductions and subsequently enact policies to meet those targets. There are

![]() $n$

countries indexed by

$n$

countries indexed by

![]() $i = 1, \ldots ,n$

. We will focus on the decision making of a representative nation that is governed by one of two governments,

$i = 1, \ldots ,n$

. We will focus on the decision making of a representative nation that is governed by one of two governments,

![]() $g \in \left\{ {{\rm{G}},{\rm{\;\;B}}} \right\}$

(and omit the subscript

$g \in \left\{ {{\rm{G}},{\rm{\;\;B}}} \right\}$

(and omit the subscript

![]() $i$

where it is not confusing). Governments vary in their marginal costs of implementing emissions reductions,

$i$

where it is not confusing). Governments vary in their marginal costs of implementing emissions reductions,

![]() ${\lambda _{\rm{g}}}$

. A “Green” government G faces lower marginal costs than a “Brown” government B, so

${\lambda _{\rm{g}}}$

. A “Green” government G faces lower marginal costs than a “Brown” government B, so

![]() ${\lambda _{\rm{G}}} \lt {\lambda _{\rm{B}}}$

. The nation also includes a median voter M, such that

${\lambda _{\rm{G}}} \lt {\lambda _{\rm{B}}}$

. The nation also includes a median voter M, such that

![]() ${\lambda _{\rm{G}}} \lt {\lambda _{\rm{M}}} \lt {\lambda _{\rm{B}}}$

.

${\lambda _{\rm{G}}} \lt {\lambda _{\rm{M}}} \lt {\lambda _{\rm{B}}}$

.

Each country initially sets a target,

![]() $y \in {\mathbb{R}_ + }$

, which is analogous to their NDC in the Paris framework. This is the overall reduction in carbon emissions to be achieved by the nation by the end of the pledge-and-review period. After setting their targets, nations implement mitigation strategies and other policy measures designed to meet their targets,

$y \in {\mathbb{R}_ + }$

, which is analogous to their NDC in the Paris framework. This is the overall reduction in carbon emissions to be achieved by the nation by the end of the pledge-and-review period. After setting their targets, nations implement mitigation strategies and other policy measures designed to meet their targets,

![]() $a \in {\mathbb{R}_ + }$

. We endow actors of our representative nation with the following utility function over policy:

$a \in {\mathbb{R}_ + }$

. We endow actors of our representative nation with the following utility function over policy:

where

![]() $A = \mathop \sum \nolimits_i {a_i}$

is global emissions reductions. We suppress dependence on

$A = \mathop \sum \nolimits_i {a_i}$

is global emissions reductions. We suppress dependence on

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() ${\lambda _g}$

where it is not confusing, writing

${\lambda _g}$

where it is not confusing, writing

![]() ${u_g}\left( a \right)$

.

${u_g}\left( a \right)$

.

All nations benefit when others enact policies to reduce emissions, so utility is increasing in the mitigation efforts of other countries, but mitigation is costly at home. Pursuing more ambitious reductions has increasing marginal costs, as reflected by the quadratic term, with

![]() ${\lambda _g}$

parameterizing the magnitude of these marginal costs. In what follows, it will be convenient to denote the reduction target that maximizes this function as actor

${\lambda _g}$

parameterizing the magnitude of these marginal costs. In what follows, it will be convenient to denote the reduction target that maximizes this function as actor

![]() $g$

’s “ideal point,”

$g$

’s “ideal point,”

![]() ${\tilde a_g} = {1 \over {{\lambda _g}}}$

.

${\tilde a_g} = {1 \over {{\lambda _g}}}$

.

After nations set their targets but prior to the implementation of mitigation policy, there is an election in our representative nation. We place the election in between these two points of the game in order to study the electoral incentives to enact different commitments, which, as we shall see, will indirectly affect the choices of mitigation policy as well. The election is determined by the median voter M, who incurs costs to adjust to mitigation strategies such that

![]() ${\lambda _{\rm{G}}} \lt {\lambda _{\rm{M}}} \lt {\lambda _{\rm{B}}}$

. That is, the median voter wants greater emissions reductions than the Brown government, but does not share the ambition of the Green government. To construct examples, we let

${\lambda _{\rm{G}}} \lt {\lambda _{\rm{M}}} \lt {\lambda _{\rm{B}}}$

. That is, the median voter wants greater emissions reductions than the Brown government, but does not share the ambition of the Green government. To construct examples, we let

![]() ${\lambda _{\rm{M}}} = {{{\lambda _{\rm{B}}} + {\lambda _{\rm{G}}}} \over 2}$

. The median voter is prospective, and votes for the Green government if and only if the payoff from electing the Green government exceeds that from electing the Brown government. In addition to observing the pledge

${\lambda _{\rm{M}}} = {{{\lambda _{\rm{B}}} + {\lambda _{\rm{G}}}} \over 2}$

. The median voter is prospective, and votes for the Green government if and only if the payoff from electing the Green government exceeds that from electing the Brown government. In addition to observing the pledge

![]() $y$

, the median voter observes valence shocks

$y$

, the median voter observes valence shocks

![]() ${\mu _{\rm{G}}}$

and

${\mu _{\rm{G}}}$

and

![]() ${\mu _{\rm{B}}}$

, which represent the value of both parties on all other electorally salient dimensions beyond mitigation policy. Let

${\mu _{\rm{B}}}$

, which represent the value of both parties on all other electorally salient dimensions beyond mitigation policy. Let

![]() $\mu = {\mu _{\rm{B}}} - {\mu _{\rm{G}}}$

, such that

$\mu = {\mu _{\rm{B}}} - {\mu _{\rm{G}}}$

, such that

![]() $\mu \sim F\left( \cdot \right)$

, with associated density

$\mu \sim F\left( \cdot \right)$

, with associated density

![]() $F{\rm{'}}\left( \cdot \right)$

. Thus the median voter prefers the Green government if and only if

$F{\rm{'}}\left( \cdot \right)$

. Thus the median voter prefers the Green government if and only if

so

![]() $G$

’s probability of election is

$G$

’s probability of election is

![]() $F\left( {{u_{\rm{M}}}\left( {{a_{\rm{G}}}} \right) - {u_{\rm{M}}}\left( {{a_{\rm{B}}}} \right)} \right)$

.

$F\left( {{u_{\rm{M}}}\left( {{a_{\rm{G}}}} \right) - {u_{\rm{M}}}\left( {{a_{\rm{B}}}} \right)} \right)$

.

Finally, as the pledge-and-review period ends, nations reconvene for a “global stocktake” that examines how successful countries were in implementing their targets. This amounts to determining the distance between

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $y$

. We assume that each

$y$

. We assume that each

![]() $a$

is imperfectly observed: the international community observes a noisy signal of the reduction measures

$a$

is imperfectly observed: the international community observes a noisy signal of the reduction measures

![]() $x = a + \varepsilon $

, where

$x = a + \varepsilon $

, where

![]() $\varepsilon \sim N\left( {0,{1 \over \beta }} \right)$

. If it is determined that country

$\varepsilon \sim N\left( {0,{1 \over \beta }} \right)$

. If it is determined that country

![]() $i$

failed to reach its target (that is,

$i$

failed to reach its target (that is,

![]() $x \lt y$

), then the governing party in country

$x \lt y$

), then the governing party in country

![]() $i$

is “shamed” and incurs a cost

$i$

is “shamed” and incurs a cost

![]() ${\sigma _g} \in {\mathbb{R}_ + }$

. Since these costs are party-specific, we allow the impact of shaming to vary across parties. Although not necessary for our results, we may anticipate that the Green party faces a larger cost for failing to follow through on its commitment than the Brown party. Thus, given a commitment

${\sigma _g} \in {\mathbb{R}_ + }$

. Since these costs are party-specific, we allow the impact of shaming to vary across parties. Although not necessary for our results, we may anticipate that the Green party faces a larger cost for failing to follow through on its commitment than the Brown party. Thus, given a commitment

![]() $y$

and effort level

$y$

and effort level

![]() $a$

, the ruling party is shamed with probability

$a$

, the ruling party is shamed with probability

![]() ${\rm{\Phi }}\left( {\sqrt \beta \left( {y - a} \right)} \right)$

, where

${\rm{\Phi }}\left( {\sqrt \beta \left( {y - a} \right)} \right)$

, where

![]() ${\rm{\Phi }}\left( \cdot \right)$

and

${\rm{\Phi }}\left( \cdot \right)$

and

![]() $\phi \left( \cdot \right)$

are the cumulative distribution and probability density functions for the standard normal, respectively. Observe that, while the shaming cost does not depend on the difference between

$\phi \left( \cdot \right)$

are the cumulative distribution and probability density functions for the standard normal, respectively. Observe that, while the shaming cost does not depend on the difference between

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $y$

, leaders have varying expectations about the probability they will be shamed as a function of how much effort they put into fulfilling the commitment.

$y$

, leaders have varying expectations about the probability they will be shamed as a function of how much effort they put into fulfilling the commitment.

While the framers of Paris had hoped that naming and shaming could originate from international and domestic sources,Footnote

48

our preferred interpretation is that the shaming cost is reputational and levied on noncompliant states by other nations. This is different from an endogenous cost levied on leaders by voters,Footnote

49

but this strategic dynamic is explored elsewhere in the literature.Footnote

50

An external source of shaming also comports with experimental evidence that individuals are more likely to support commitments if they know their leaders could be shamed.Footnote

51

Hence, the shaming cost

![]() ${\sigma _g}$

should be thought of as conceptually distinct from the median voter’s decision to retain or replace the incumbent party given the observed commitment (prior to implementation). We understand that there may be credibility or collective-action problems in terms of who does the shaming internationally,Footnote

52

but the probabilistic nature of shaming in our model captures these concerns in reduced form.

${\sigma _g}$

should be thought of as conceptually distinct from the median voter’s decision to retain or replace the incumbent party given the observed commitment (prior to implementation). We understand that there may be credibility or collective-action problems in terms of who does the shaming internationally,Footnote

52

but the probabilistic nature of shaming in our model captures these concerns in reduced form.

Finally, let

![]() $\rho \in \left\{ {0,1} \right\}$

denote whether the median voter elects the Green party (

$\rho \in \left\{ {0,1} \right\}$

denote whether the median voter elects the Green party (

![]() $\rho = 1$

) or the Brown party (

$\rho = 1$

) or the Brown party (

![]() $\rho = 0$

). Then the governments’ payoffs from making a commitment

$\rho = 0$

). Then the governments’ payoffs from making a commitment

![]() $y$

are

$y$

are

This demonstrates that, when choosing climate commitments, leaders care about mitigation policy outcomes, the ability to influence electoral outcomes through the behavior of the median voter, and winning elections. The party that wins the election enjoys benefit

![]() ${\rm{\Psi }} \gt 0$

. Notice also that only the party in power incurs the shaming cost

${\rm{\Psi }} \gt 0$

. Notice also that only the party in power incurs the shaming cost

![]() ${\sigma _g}$

if their mitigation efforts are judged to fall short of the nation’s climate commitment. We do not require that the median voter or the party out of power pay the shaming cost, although many of the main features of the equilibrium would be robust to this modification.

${\sigma _g}$

if their mitigation efforts are judged to fall short of the nation’s climate commitment. We do not require that the median voter or the party out of power pay the shaming cost, although many of the main features of the equilibrium would be robust to this modification.

The timing of the game is summarized as follows.

-

1. Governments commit to pledges

${y_g}$

.

${y_g}$

. -

2. The median voter observes their nation’s pledge

$y$

and votes to elect either the Green government G or the Brown government B.

$y$

and votes to elect either the Green government G or the Brown government B. -

3. The elected government implements mitigation policies

${a_g}$

.

${a_g}$

. -

4. Nations review global mitigation progress and observe

$x$

, shaming country

$x$

, shaming country

$i$

if

$i$

if

$x \lt y$

.

$x \lt y$

.

We analyze the subgame perfect equilibrium. The incumbent party chooses a climate commitment

![]() ${y_g} \in {\mathbb{R}_ + }$

. The median voter’s strategy is a mapping from the expected efforts given

${y_g} \in {\mathbb{R}_ + }$

. The median voter’s strategy is a mapping from the expected efforts given

![]() $y$

and the valence shock into a vote choice for G or B. Finally, the party that wins the election chooses effort

$y$

and the valence shock into a vote choice for G or B. Finally, the party that wins the election chooses effort

![]() ${a_g} \in {\mathbb{R}_ + }$

given their nation’s prior commitment.

${a_g} \in {\mathbb{R}_ + }$

given their nation’s prior commitment.

Analysis

We start with a general characterization of the subgame perfect equilibrium. Using backward induction we characterize each party’s mitigation efforts for each possible commitment, find how the efforts affect the voter’s electoral decision, and characterize the commitments that each party will make given how such commitments affect the election and subsequent mitigation efforts.

In equilibrium, a party’s climate pledge is influenced by a variety of factors, including the ability to tie the other party’s hands with respect to policy implementation as well as the ability to influence which party will win election. To isolate the properties of each of these mechanisms, we examine a series of limiting cases as the signals of mitigation efforts become precise (

![]() $\beta \to \infty $

).

$\beta \to \infty $

).

Optimal Mitigation Efforts

We first consider the emissions-reduction target pursued by government

![]() $g$

after the election. Government

$g$

after the election. Government

![]() $g$

’s expected utility is

$g$

’s expected utility is

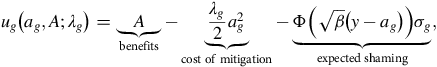

$${u_g}\left( {{a_g},A;{\lambda _g}} \right) = \underbrace A_{{\rm{benefits}}} - \underbrace {{{{\lambda _g}} \over 2}a_g^2}_{{\rm{cost}}\;{\rm{of}}\;{\rm{mitigation}}} - \underbrace {\Phi \left( {\sqrt \beta \left( {y - {a_g}} \right)} \right){\sigma _g}}_{{\rm{expected}}\;{\rm{shaming}}},$$

$${u_g}\left( {{a_g},A;{\lambda _g}} \right) = \underbrace A_{{\rm{benefits}}} - \underbrace {{{{\lambda _g}} \over 2}a_g^2}_{{\rm{cost}}\;{\rm{of}}\;{\rm{mitigation}}} - \underbrace {\Phi \left( {\sqrt \beta \left( {y - {a_g}} \right)} \right){\sigma _g}}_{{\rm{expected}}\;{\rm{shaming}}},$$

which, given the predetermined pledge

![]() $y$

, is the utility over mitigation commitments plus the probability of being shamed and incurring the cost

$y$

, is the utility over mitigation commitments plus the probability of being shamed and incurring the cost

![]() ${\sigma _g}$

for failing to meet the pledge. The optimal mitigation effort

${\sigma _g}$

for failing to meet the pledge. The optimal mitigation effort

![]() $a_{g}^{*}$

therefore solves the following first-order condition stated in Lemma 1.

$a_{g}^{*}$

therefore solves the following first-order condition stated in Lemma 1.

Lemma 1:

Given climate commitment

![]() $y$

, the government’s policy

$y$

, the government’s policy

![]() $a_g^*$

satisfies the first-order condition

$a_g^*$

satisfies the first-order condition

$${{d{u_g}\left( {{a_g},A;{\lambda _g}} \right)} \over {d{a_g}}} = 1 - {\lambda _g}a_g^{\rm{*}} + {\sigma _g}\sqrt \beta \phi \left( {\sqrt \beta \left( {y - a_g^{\rm{*}}} \right)} \right) = 0$$

$${{d{u_g}\left( {{a_g},A;{\lambda _g}} \right)} \over {d{a_g}}} = 1 - {\lambda _g}a_g^{\rm{*}} + {\sigma _g}\sqrt \beta \phi \left( {\sqrt \beta \left( {y - a_g^{\rm{*}}} \right)} \right) = 0$$

and the second-order condition

$${{{d^2}{u_g}\left( {{a_g},A;{\lambda _g}} \right)} \over {da_g^2}} = - {\lambda _g} + {\sigma _g}\beta \sqrt \beta \left( {y - a_g^{\rm{*}}} \right)\phi \left( {\sqrt \beta \left( {y - a_g^{\rm{*}}} \right)} \right) \lt 0.$$

$${{{d^2}{u_g}\left( {{a_g},A;{\lambda _g}} \right)} \over {da_g^2}} = - {\lambda _g} + {\sigma _g}\beta \sqrt \beta \left( {y - a_g^{\rm{*}}} \right)\phi \left( {\sqrt \beta \left( {y - a_g^{\rm{*}}} \right)} \right) \lt 0.$$

If the signal of effort

![]() $x$

is sufficiently noisy, there is a unique solution to the first-order condition: Equation (1). However, with precise signals, there might be two local maxima that satisfy the first-order condition, which can result in a discontinuity in the government’s optimal response. Given the technical rather than the substantive nature of this uniqueness discussion, we characterize these conditions at length in the online supplement (Lemmas A.1 and A.2).

$x$

is sufficiently noisy, there is a unique solution to the first-order condition: Equation (1). However, with precise signals, there might be two local maxima that satisfy the first-order condition, which can result in a discontinuity in the government’s optimal response. Given the technical rather than the substantive nature of this uniqueness discussion, we characterize these conditions at length in the online supplement (Lemmas A.1 and A.2).

Parties weigh the marginal costs of effort against their global marginal benefits and the possibility of being shamed and, in general, will set their effort close to their ideal point

![]() ${\tilde a_g}$

or close to the pledge

${\tilde a_g}$

or close to the pledge

![]() $y$

. Leaders will choose the former if the commitment is low enough that an effort close to their ideal point is enough to avoid being shamed, or if the commitment is so high that they prefer to accept that they are likely to be shamed. By contrast, if the commitment is not too high relative to the ideal point, then governments will make an effort closer to the target, to lower the probability of being shamed.

$y$

. Leaders will choose the former if the commitment is low enough that an effort close to their ideal point is enough to avoid being shamed, or if the commitment is so high that they prefer to accept that they are likely to be shamed. By contrast, if the commitment is not too high relative to the ideal point, then governments will make an effort closer to the target, to lower the probability of being shamed.

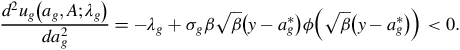

Figure 1 plots the optimal efforts of each party and the likelihood of being shamed as a function of the climate commitment

![]() $y$

. The left panel plots G’s optimal effort in green (solid line) and B’s optimal effort in brown (dashed line). Optimal efforts are non-monotonic in the commitment

$y$

. The left panel plots G’s optimal effort in green (solid line) and B’s optimal effort in brown (dashed line). Optimal efforts are non-monotonic in the commitment

![]() $y$

. If

$y$

. If

![]() $y$

is not too large, parties may find it in their interest to comply with the target as a means of avoiding shame. However, this incentive dissipates if

$y$

is not too large, parties may find it in their interest to comply with the target as a means of avoiding shame. However, this incentive dissipates if

![]() $y$

is set too ambitiously; as the costs of the effort to avoid being shamed grow, parties resign themselves to being shamed and pull back the effort to close to their ideal point. The Green party makes a greater effort than the Brown party in equilibrium because their marginal costs of effort are smaller, and making a greater effort means that G will be shamed with a smaller probability than B, as illustrated in the right panel.

$y$

is set too ambitiously; as the costs of the effort to avoid being shamed grow, parties resign themselves to being shamed and pull back the effort to close to their ideal point. The Green party makes a greater effort than the Brown party in equilibrium because their marginal costs of effort are smaller, and making a greater effort means that G will be shamed with a smaller probability than B, as illustrated in the right panel.

Figure 1. Efforts and the likelihood of shaming as a function of commitments (

![]() ${\lambda _G} = 1,{\rm{\;\;}}{\lambda _B} = 2,{\rm{\;\;}}\beta = 4,{\rm{\;\;}}{\sigma _G} = {\sigma _B} = 1$

)

${\lambda _G} = 1,{\rm{\;\;}}{\lambda _B} = 2,{\rm{\;\;}}\beta = 4,{\rm{\;\;}}{\sigma _G} = {\sigma _B} = 1$

)

Leaders’ incentives to comply ex post with international mitigation targets thus depend on how ambitiously the commitment was set relative to the ideal level and the chances that they could be shamed for noncompliance. Of course, the government in power when commitments were set need not be the government tasked with implementing policy to meet those commitments: this depends on how voters perceive the costs of future mitigation policies and the extent to which these policy concerns affect the electoral outcome.

Voting Behavior

We now consider the behavior of the median voter. When choosing whether to elect the Green government or the Brown government, M anticipates the mitigation efforts each party will make and how costly these policies will be for her. Empirical work has found that voters’ willingness to support mitigation policy is highly sensitive to the costs of those policies,Footnote

53

and the median voter’s electoral decision reflects this sensitivity. Moreover, we acknowledge that the salience of climate policy may be low to voters—although it is increasing over timeFootnote

54

—so the median voter also evaluates the two possible governments along other electorally relevant considerations, captured by the valence terms

![]() ${\mu _g}$

. Quite simply, M votes for the Green government over the Brown government when

${\mu _g}$

. Quite simply, M votes for the Green government over the Brown government when

Climate commitments affect voting outcomes through the expected cost to the median voter of the effort needed to fulfill those commitments. For any

![]() $y$

, parties implement their optimal

$y$

, parties implement their optimal

![]() $a_g^{\rm{*}}$

after the election, which the voter can anticipate. This means that, in the model, the voter observes the commitment prior to the election, and forms an expectation of the policies each party would implement should they come to office. This is not the same as punishing a party who failed to meet their commitment. Instead, the voter adjudicates the relative costliness of G and B’s expected policies against other electorally salient issues. Straightforwardly, as the Green government proposes more and more ambitious commitments relative to the Brown government, the median voter’s expected cost of voting for the Green government increases, which makes the Green party less attractive electorally. We call the difference in M’s policy utility from G versus B’s equilibrium efforts their “bias” toward the Green party, denoted

$a_g^{\rm{*}}$

after the election, which the voter can anticipate. This means that, in the model, the voter observes the commitment prior to the election, and forms an expectation of the policies each party would implement should they come to office. This is not the same as punishing a party who failed to meet their commitment. Instead, the voter adjudicates the relative costliness of G and B’s expected policies against other electorally salient issues. Straightforwardly, as the Green government proposes more and more ambitious commitments relative to the Brown government, the median voter’s expected cost of voting for the Green government increases, which makes the Green party less attractive electorally. We call the difference in M’s policy utility from G versus B’s equilibrium efforts their “bias” toward the Green party, denoted

![]() ${\rm{\Delta }}$

; the Green party is therefore elected with probability

${\rm{\Delta }}$

; the Green party is therefore elected with probability

![]() $F\left( {\rm{\Delta }} \right)$

.

$F\left( {\rm{\Delta }} \right)$

.

Optimal Climate Commitments

We now turn to the optimal pledges that different governments would set. Leaders care about the policy returns from committing to a pledge

![]() $y$

, and about holding office. These concerns in turn affect the median voter’s willingness to re-elect incumbents based on the prospective mitigation policies to be chosen after the election. The choice of climate commitment affects party G’s payoff as follows.

$y$

, and about holding office. These concerns in turn affect the median voter’s willingness to re-elect incumbents based on the prospective mitigation policies to be chosen after the election. The choice of climate commitment affects party G’s payoff as follows.

With probability

![]() $F\left( {\rm{\Delta }} \right)$

, G wins the election, gets office benefits

$F\left( {\rm{\Delta }} \right)$

, G wins the election, gets office benefits

![]() ${\rm{\Psi }}$

, and implements effort

${\rm{\Psi }}$

, and implements effort

![]() $a_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}$

, knowing that with probability

$a_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}$

, knowing that with probability

![]() ${\rm{\Phi }}\left( {\sqrt \beta \left( {y - a_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}} \right)} \right)$

they will be shamed. However, with probability

${\rm{\Phi }}\left( {\sqrt \beta \left( {y - a_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}} \right)} \right)$

they will be shamed. However, with probability

![]() $1 - F\left( {\rm{\Delta }} \right)$

, party B wins the election and G receives the policy payoff associated with B’s equilibrium effort.

$1 - F\left( {\rm{\Delta }} \right)$

, party B wins the election and G receives the policy payoff associated with B’s equilibrium effort.

Likewise, party B’s payoff is

We write

![]() $y_g^{\rm{*}}$

for the optimal climate commitment party

$y_g^{\rm{*}}$

for the optimal climate commitment party

![]() $g$

chooses, maximizing their payoff,

$g$

chooses, maximizing their payoff,

Given our backward induction analysis, we can now straightforwardly summarize the preceding discussion of optimal effort, voting decisions, and selection of climate commitments.

Proposition 1:

In subgame perfect equilibria, party

![]() $G$

selects

$G$

selects

![]() $y_G^*$

and implements effort

$y_G^*$

and implements effort

![]() $a_G^*$

if elected; party

$a_G^*$

if elected; party

![]() $B$

selects

$B$

selects

![]() $y_B^*$

and implements effort

$y_B^*$

and implements effort

![]() $a_B^*$

if elected. The median voter votes for

$a_B^*$

if elected. The median voter votes for

![]() $G$

if and only if

$G$

if and only if

![]() $\mu \le \Delta \left( {a_G^*,a_B^*;y} \right)$

; and

$\mu \le \Delta \left( {a_G^*,a_B^*;y} \right)$

; and

![]() $G$

is elected with probability

$G$

is elected with probability

![]() $F\left( {\Delta \left( {a_G^*,a_B^*;y} \right)} \right)$

.

$F\left( {\Delta \left( {a_G^*,a_B^*;y} \right)} \right)$

.

A party’s choice of the commitment

![]() $y$

shapes downstream mitigation efforts after the election through several channels. Climate commitments can thus be useful in policy terms because parties may be able to tie the hands of their competitors through their choice of pledge. Moreover, because pledges affect effort levels, they affect who wins the election. This latter factor is encapsulated in the commitment’s effect on

$y$

shapes downstream mitigation efforts after the election through several channels. Climate commitments can thus be useful in policy terms because parties may be able to tie the hands of their competitors through their choice of pledge. Moreover, because pledges affect effort levels, they affect who wins the election. This latter factor is encapsulated in the commitment’s effect on

![]() ${\rm{\Delta }}$

, the net electoral value of G relative to B. In such a general setting, it is difficult to isolate the substantive impact of these competing policy and office incentives. As the online supplement explores, party payoffs may look very different depending on which incentives dominate. To isolate the influence of each factor on climate commitments, we look at a series of limiting cases. These limiting cases also help demonstrate how variation in primitives isolates different concerns governments have in choosing their climate commitments, and thus ultimately drives variation in observed outcomes.

${\rm{\Delta }}$

, the net electoral value of G relative to B. In such a general setting, it is difficult to isolate the substantive impact of these competing policy and office incentives. As the online supplement explores, party payoffs may look very different depending on which incentives dominate. To isolate the influence of each factor on climate commitments, we look at a series of limiting cases. These limiting cases also help demonstrate how variation in primitives isolates different concerns governments have in choosing their climate commitments, and thus ultimately drives variation in observed outcomes.

Limiting Case: Precise Shaming

We now present a special case of our model in which the uncertainty around shaming vanishes,

![]() $\beta \to \infty $

, meaning leaders know with certainty whether they will be shamed. Optimal efforts are fairly simple in this case: the election winner will either comply with the target or implement their ideal effort level. If the target

$\beta \to \infty $

, meaning leaders know with certainty whether they will be shamed. Optimal efforts are fairly simple in this case: the election winner will either comply with the target or implement their ideal effort level. If the target

![]() $y$

is low enough, leaders can implement their ideal point and avoid shaming. Increasing the ambition of the climate commitment (

$y$

is low enough, leaders can implement their ideal point and avoid shaming. Increasing the ambition of the climate commitment (

![]() $y \gt {\tilde a_g}$

) means leaders face a trade-off between implementing the target versus implementing their ideal point and incurring the costs of being shamed. If a party complies with the pre-existing target, their payoff is

$y \gt {\tilde a_g}$

) means leaders face a trade-off between implementing the target versus implementing their ideal point and incurring the costs of being shamed. If a party complies with the pre-existing target, their payoff is

![]() ${y_g} - {{{\lambda _g}} \over 2}y_g^2$

, where the first term corresponds to the benefits of implementing the target and the quadratic term represents the costs. Alternatively, the party might implement its ideal point and get shamed, for a payoff of

${y_g} - {{{\lambda _g}} \over 2}y_g^2$

, where the first term corresponds to the benefits of implementing the target and the quadratic term represents the costs. Alternatively, the party might implement its ideal point and get shamed, for a payoff of

![]() ${\tilde a_g} - {{{\lambda _g}} \over 2}\tilde a_g^2 - {\sigma _g}$

. Hence, whenever

${\tilde a_g} - {{{\lambda _g}} \over 2}\tilde a_g^2 - {\sigma _g}$

. Hence, whenever

![]() $y \le {\hat y_g} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\lambda _g}{\sigma _g}} } \over {{\lambda _g}}}$

, leaders prefer to comply with the target instead of implementing their ideal point and getting shamed. If the pledge is set too ambitiously,

$y \le {\hat y_g} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\lambda _g}{\sigma _g}} } \over {{\lambda _g}}}$

, leaders prefer to comply with the target instead of implementing their ideal point and getting shamed. If the pledge is set too ambitiously,

![]() $y \gt {\hat y_g}$

, then leaders will revert to implementing their ideal level of effort, knowing they will be shamed. Thus:

$y \gt {\hat y_g}$

, then leaders will revert to implementing their ideal level of effort, knowing they will be shamed. Thus:

Corollary 1:

Let

![]() $\beta \to \infty $

. Government

$\beta \to \infty $

. Government

![]() $g$

pursues the mitigation effort

$g$

pursues the mitigation effort

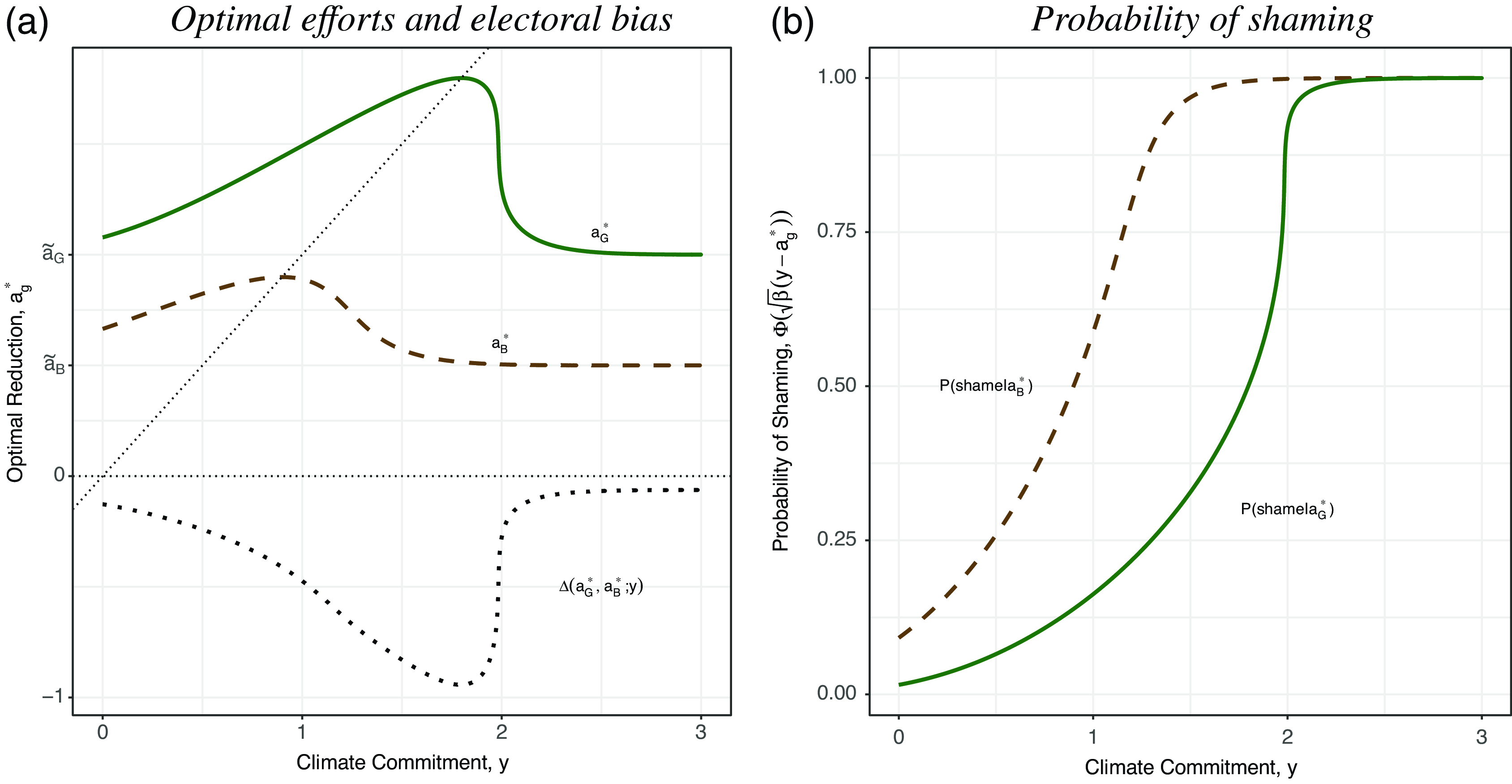

$$a_g^{\rm{*}}\left( y \right) = \Bigg\lbrace {\matrix{ {{{\tilde a}_g}} \hfill {{\,{if}}y \lt {{\tilde a}_g}} \hfill \cr y \hfill {{\,{if}}{{\tilde a}_g} \le y \le {{\hat y}_g}} \hfill \cr {{{\tilde a}_g}} \hfill {{\,{if}}y \gt {{\hat y}_g}.} \hfill \cr } }.$$

$$a_g^{\rm{*}}\left( y \right) = \Bigg\lbrace {\matrix{ {{{\tilde a}_g}} \hfill {{\,{if}}y \lt {{\tilde a}_g}} \hfill \cr y \hfill {{\,{if}}{{\tilde a}_g} \le y \le {{\hat y}_g}} \hfill \cr {{{\tilde a}_g}} \hfill {{\,{if}}y \gt {{\hat y}_g}.} \hfill \cr } }.$$

This tells us the downstream policies each party will implement if elected, given pledge

![]() $y$

. We now turn to thinking about the incentives parties face when choosing the commitments themselves. Parties might pick a commitment in order to tie the hands of an opposition party to implement a policy they like. Alternatively, a party might pick a commitment to gain an electoral advantage. We examine each of these mechanisms, using the precise shaming technology.

$y$

. We now turn to thinking about the incentives parties face when choosing the commitments themselves. Parties might pick a commitment in order to tie the hands of an opposition party to implement a policy they like. Alternatively, a party might pick a commitment to gain an electoral advantage. We examine each of these mechanisms, using the precise shaming technology.

Tying Hands

Suppose first that parties choose climate commitments solely for their policy value. To isolate this mechanism, we assume that holding office is irrelevant,

![]() ${\rm{\Psi }} \to 0$

, and that elections are not sensitive to climate policy,

${\rm{\Psi }} \to 0$

, and that elections are not sensitive to climate policy,

![]() $F{\rm{'}} \to 0$

. Setting a commitment is valuable insofar as it ties politicians’ hands when enacting future mitigation efforts. Since climate commitments serve as endogenous reference points, they define the scope of policies that could be implemented in the future. Thus, choosing a commitment has value if incumbents can ensure that potential electoral opposition will not deviate from climate policies they like. Parties set commitments to affect the implementation of effort

$F{\rm{'}} \to 0$

. Setting a commitment is valuable insofar as it ties politicians’ hands when enacting future mitigation efforts. Since climate commitments serve as endogenous reference points, they define the scope of policies that could be implemented in the future. Thus, choosing a commitment has value if incumbents can ensure that potential electoral opposition will not deviate from climate policies they like. Parties set commitments to affect the implementation of effort

![]() $a_g^{\rm{*}}$

after the election.

$a_g^{\rm{*}}$

after the election.

Tying hands is particularly important for G, who sets a commitment

![]() $y$

that forces B to increase its climate investments over what they would be without that commitment. Ideally, G would like B to implement G’s ideal point, which relies on the possibility that B could be sufficiently shamed for failing to follow through on this policy. If the shaming effect

$y$

that forces B to increase its climate investments over what they would be without that commitment. Ideally, G would like B to implement G’s ideal point, which relies on the possibility that B could be sufficiently shamed for failing to follow through on this policy. If the shaming effect

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

is insufficient for G to force B to implement G’s ideal point, then G sets the target to the largest policy that B would be willing to fulfill, should B come to power after the election.

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

is insufficient for G to force B to implement G’s ideal point, then G sets the target to the largest policy that B would be willing to fulfill, should B come to power after the election.

Formally, we define

![]() $\hat \sigma = {{{{({\lambda _{\rm{B}}} - {\lambda _{\rm{G}}})}^2}} \over {2\lambda _{\rm{G}}^2{\lambda _{\rm{B}}}}}$

as the smallest shaming cost such that B would be willing to adhere to a climate commitment at G’s ideal point (that is,

$\hat \sigma = {{{{({\lambda _{\rm{B}}} - {\lambda _{\rm{G}}})}^2}} \over {2\lambda _{\rm{G}}^2{\lambda _{\rm{B}}}}}$

as the smallest shaming cost such that B would be willing to adhere to a climate commitment at G’s ideal point (that is,

![]() ${u_{\rm{B}}}\left( {{{\tilde a}_{\rm{G}}}} \right) = {u_{\rm{B}}}\left( {{{\tilde a}_{\rm{B}}}} \right) - \hat \sigma $

). For large costs of shaming, in particular

${u_{\rm{B}}}\left( {{{\tilde a}_{\rm{G}}}} \right) = {u_{\rm{B}}}\left( {{{\tilde a}_{\rm{B}}}} \right) - \hat \sigma $

). For large costs of shaming, in particular

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \ge \hat \sigma $

, G can fully tie B’s hands and force it to implement G’s ideal point by choosing

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \ge \hat \sigma $

, G can fully tie B’s hands and force it to implement G’s ideal point by choosing

![]() $y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}} = {\tilde a_{\rm{G}}}$

. This ensures that effort will be set at G’s ideal point, regardless of who wins the election. However, if shaming costs are lower (

$y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}} = {\tilde a_{\rm{G}}}$

. This ensures that effort will be set at G’s ideal point, regardless of who wins the election. However, if shaming costs are lower (

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \lt \hat \sigma $

), G cannot induce B to exert effort at G’s ideal point

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \lt \hat \sigma $

), G cannot induce B to exert effort at G’s ideal point

![]() ${\tilde a_{\rm{G}}}$

; B would rather be shamed than implement such ambitious climate reforms. Instead, G ties B’s hands to the greatest extent possible by setting

${\tilde a_{\rm{G}}}$

; B would rather be shamed than implement such ambitious climate reforms. Instead, G ties B’s hands to the greatest extent possible by setting

![]() $y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}} = {\hat y_{\rm{B}}} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\lambda _{\rm{B}}}{\sigma _{\rm{B}}}} } \over {{\lambda _{\rm{B}}}}}$

. This pledge is the greatest

$y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}} = {\hat y_{\rm{B}}} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\lambda _{\rm{B}}}{\sigma _{\rm{B}}}} } \over {{\lambda _{\rm{B}}}}}$

. This pledge is the greatest

![]() $y$

that B would be willing to comply with, making B indifferent between (a) exerting effort at the pledge

$y$

that B would be willing to comply with, making B indifferent between (a) exerting effort at the pledge

![]() $y$

and avoiding shaming, and (b) implementing its ideal point

$y$

and avoiding shaming, and (b) implementing its ideal point

![]() ${\tilde a_{\rm{B}}}$

and incurring the shaming cost

${\tilde a_{\rm{B}}}$

and incurring the shaming cost

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

.

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

.

By contrast, B cannot tie G’s hands at all because G ideally prefers to exert more effort than B. The best B can do is to set a target at no more than its ideal point; this allows B to remain in compliance with the agreement should

![]() $B$

win the election. If G wins the election, G would implement its own ideal point. Thus:

$B$

win the election. If G wins the election, G would implement its own ideal point. Thus:

Proposition 2:

Let

![]() $\beta \to \infty $

,

$\beta \to \infty $

,

![]() $\Psi \to 0$

, and

$\Psi \to 0$

, and

![]() $F' \to 0$

.

$F' \to 0$

.

![]() $G$

’s optimal commitment is

$G$

’s optimal commitment is

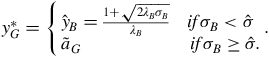

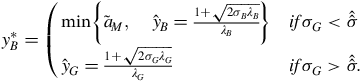

$$y_G^{\rm{*}} = \Bigg\lbrace{\matrix{ {{{\hat y}_B} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\lambda _B}{\sigma _B}} } \over {{\lambda _B}}}} \hfill & {{\\{if}}{\sigma _B} \lt \hat \sigma } \hfill \cr {{{\tilde a}_G}} \hfill & {{\,{if}}{\sigma _B} \ge \hat \sigma .} \hfill \cr } } .$$

$$y_G^{\rm{*}} = \Bigg\lbrace{\matrix{ {{{\hat y}_B} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\lambda _B}{\sigma _B}} } \over {{\lambda _B}}}} \hfill & {{\\{if}}{\sigma _B} \lt \hat \sigma } \hfill \cr {{{\tilde a}_G}} \hfill & {{\,{if}}{\sigma _B} \ge \hat \sigma .} \hfill \cr } } .$$

![]() $B$

’s optimal commitment is any

$B$

’s optimal commitment is any

Figure 2 illustrates the optimal climate commitments as a function of the shaming cost

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

. The solid green and dot-dashed brown lines plot the two parties’ optimal commitment. If parties care about only the policy value of climate commitments, then the Green party can use climate pledges to drag the Brown party’s effort on climate change as close to Green’s ideal point as possible. Ideally, each party would like to implement their own ideal point,

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

. The solid green and dot-dashed brown lines plot the two parties’ optimal commitment. If parties care about only the policy value of climate commitments, then the Green party can use climate pledges to drag the Brown party’s effort on climate change as close to Green’s ideal point as possible. Ideally, each party would like to implement their own ideal point,

![]() ${y_g} = {\tilde a_g}$

, fully tying the hands of the other party. However, if

${y_g} = {\tilde a_g}$

, fully tying the hands of the other party. However, if

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

is too small, G cannot completely tie B’s hands; instead, G sets

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

is too small, G cannot completely tie B’s hands; instead, G sets

![]() $y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}$

such that B invests the most effort it would be willing to without being shamed. This is seen on the left-hand side of the figure as G’s increasing optimal target when

$y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}$

such that B invests the most effort it would be willing to without being shamed. This is seen on the left-hand side of the figure as G’s increasing optimal target when

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \le \hat \sigma $

. B, who cannot tie G’s hands, simply sets the most ambitious commitment that allows the implementation of its ideal point.

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \le \hat \sigma $

. B, who cannot tie G’s hands, simply sets the most ambitious commitment that allows the implementation of its ideal point.

Figure 2. Climate commitments with hands-tying incentives

Winning Office

We now examine how parties can use climate commitments to help them remain in elected office. To model these electoral incentives, we let the value of office-holding grow large enough that winning office becomes the dominant incentive for parties,

![]() ${\rm{\Psi }} \to \infty $

. The choice of pledge then depends on maximizing the probability of winning the election; recall that the median voter votes for G with probability

${\rm{\Psi }} \to \infty $

. The choice of pledge then depends on maximizing the probability of winning the election; recall that the median voter votes for G with probability

![]() $F\left( {{\rm{\Delta }}\left( {a_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}},a_{\rm{B}}^{\rm{*}};y} \right)} \right)$

, where

$F\left( {{\rm{\Delta }}\left( {a_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}},a_{\rm{B}}^{\rm{*}};y} \right)} \right)$

, where

![]() ${\rm{\Delta }}\left( {a_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}},a_{\rm{B}}^{\rm{*}};y} \right) = {u_{\rm{M}}}\left( {a_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}} \right) - {u_{\rm{M}}}\left( {a_{\rm{B}}^{\rm{*}}} \right)$

is the voter’s “bias” toward the Green party. The intuition is fairly simple: the Green party wants to maximize this bias, while the Brown party seeks to minimize it. At each party’s baseline—that is, the scenario in which they would commit to their ideal points—the Brown party has an electoral edge over the Green party,

${\rm{\Delta }}\left( {a_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}},a_{\rm{B}}^{\rm{*}};y} \right) = {u_{\rm{M}}}\left( {a_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}} \right) - {u_{\rm{M}}}\left( {a_{\rm{B}}^{\rm{*}}} \right)$

is the voter’s “bias” toward the Green party. The intuition is fairly simple: the Green party wants to maximize this bias, while the Brown party seeks to minimize it. At each party’s baseline—that is, the scenario in which they would commit to their ideal points—the Brown party has an electoral edge over the Green party,

![]() ${\rm{\Delta }}\left( {{{\tilde a}_{\rm{G}}},{{\tilde a}_{\rm{B}}};y} \right) \lt 0$

, because Brown would impose fewer costs on the voter with its target.Footnote

55

In the online supplement, we provide a more technical explanation of this bias and discuss how it changes as a function of possible commitments given a sufficiently large shaming cost

${\rm{\Delta }}\left( {{{\tilde a}_{\rm{G}}},{{\tilde a}_{\rm{B}}};y} \right) \lt 0$

, because Brown would impose fewer costs on the voter with its target.Footnote

55

In the online supplement, we provide a more technical explanation of this bias and discuss how it changes as a function of possible commitments given a sufficiently large shaming cost

![]() ${\sigma _g}$

.

${\sigma _g}$

.

If parties care primarily about holding office, then G pledges a commitment that maximizes the electoral bias, while B wants to minimize it. For the Green party, the best-case scenario occurs if the commitment motivates both parties to make the same effort downstream, taking Brown’s electoral edge to zero. If shaming costs are large enough, such that the Brown party would abide by pledges above its ideal point, Green commits to its own ideal point

![]() $y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}} = {\tilde a_{\rm{G}}}$

. This is the largest commitment that Green would prefer and, if Brown complies with it too, nullifies the electoral bias. However, if

$y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}} = {\tilde a_{\rm{G}}}$

. This is the largest commitment that Green would prefer and, if Brown complies with it too, nullifies the electoral bias. However, if

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

is small, then the Green party chooses the largest commitment that the Brown party would follow, thus minimizing but not entirely removing Brown’s electoral advantage. By contrast, to maximize its electoral prospects, the Brown party wants to pick a commitment that exacerbates the costs imposed on the voter should the Green party win the election. This makes the Brown party look even more electorally attractive in comparison.

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

is small, then the Green party chooses the largest commitment that the Brown party would follow, thus minimizing but not entirely removing Brown’s electoral advantage. By contrast, to maximize its electoral prospects, the Brown party wants to pick a commitment that exacerbates the costs imposed on the voter should the Green party win the election. This makes the Brown party look even more electorally attractive in comparison.

The next proposition specifies the optimal commitments for office-seeking parties for all possible shaming costs. For ease of exposition we focus on the special case where both parties face the same shaming cost,

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} = {\sigma _{\rm{G}}} = \sigma $

. In the online supplement, Proposition A.1 relaxes this assumption and finds largely identical behavior.

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} = {\sigma _{\rm{G}}} = \sigma $

. In the online supplement, Proposition A.1 relaxes this assumption and finds largely identical behavior.

Proposition 3:

Let

![]() $\beta \to \infty $

,

$\beta \to \infty $

,

![]() $\Psi \to \infty $

,

$\Psi \to \infty $

,

![]() $F' \gt 0$

and

$F' \gt 0$

and

![]() ${\sigma _B} = {\sigma _G} = \sigma $

. There exist thresholds

${\sigma _B} = {\sigma _G} = \sigma $

. There exist thresholds

![]() $\bar \sigma $

,

$\bar \sigma $

,

![]() $\hat \sigma $

, and

$\hat \sigma $

, and

![]() $\hat \sigma $

such that

$\hat \sigma $

such that

![]() $G$

’s optimal climate commitment is

$G$

’s optimal climate commitment is

$$y_G^{\rm{*}} = \left( {\matrix{ {y \le {{\tilde a}_B} \, or \, y \in \left( {{{\hat y}_B},{{\tilde a}_G}} \right]} \hfill & {if{\sigma _B} \lt \bar \sigma } \hfill \cr {{{\hat y}_B} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\sigma _B}{\lambda _B}} } \over {{\lambda _B}}}} \hfill & {if\bar \sigma \le {\sigma _B} \le \hat \sigma } \hfill \cr {{{\tilde a}_G}} \hfill & {if{\sigma _B} \gt \hat \sigma .} \hfill \cr } } \right.$$

$$y_G^{\rm{*}} = \left( {\matrix{ {y \le {{\tilde a}_B} \, or \, y \in \left( {{{\hat y}_B},{{\tilde a}_G}} \right]} \hfill & {if{\sigma _B} \lt \bar \sigma } \hfill \cr {{{\hat y}_B} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\sigma _B}{\lambda _B}} } \over {{\lambda _B}}}} \hfill & {if\bar \sigma \le {\sigma _B} \le \hat \sigma } \hfill \cr {{{\tilde a}_G}} \hfill & {if{\sigma _B} \gt \hat \sigma .} \hfill \cr } } \right.$$

![]() $B$

’s optimal commitment is

$B$

’s optimal commitment is

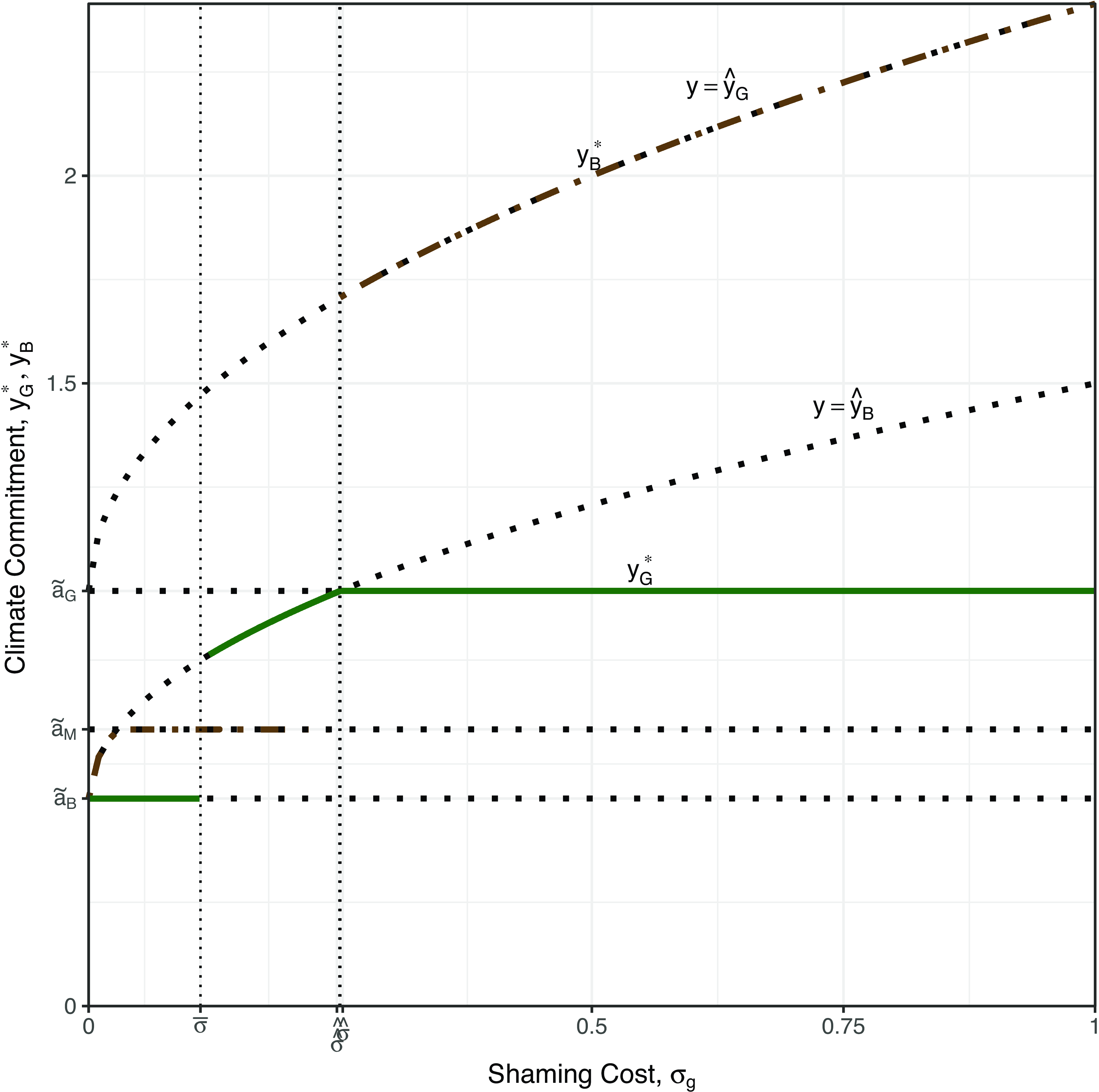

$$y_B^{\rm{*}} = \left( {\matrix{ {{\rm{min}}\left\{ {{{\tilde a}_M},{\rm{\;\;\;\;}}{{\hat y}_B} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\sigma _B}{\lambda _B}} } \over {{\lambda _B}}}} \right\}} \hfill & {if{\sigma _G} \lt \hat \sigma } \hfill \cr {{{\hat y}_G} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\sigma _G}{\lambda _G}} } \over {{\lambda _G}}}} \hfill & {if{\sigma _G} \gt\hat \sigma .} \hfill \cr} } \right.$$

$$y_B^{\rm{*}} = \left( {\matrix{ {{\rm{min}}\left\{ {{{\tilde a}_M},{\rm{\;\;\;\;}}{{\hat y}_B} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\sigma _B}{\lambda _B}} } \over {{\lambda _B}}}} \right\}} \hfill & {if{\sigma _G} \lt \hat \sigma } \hfill \cr {{{\hat y}_G} = {{1 + \sqrt {2{\sigma _G}{\lambda _G}} } \over {{\lambda _G}}}} \hfill & {if{\sigma _G} \gt\hat \sigma .} \hfill \cr} } \right.$$

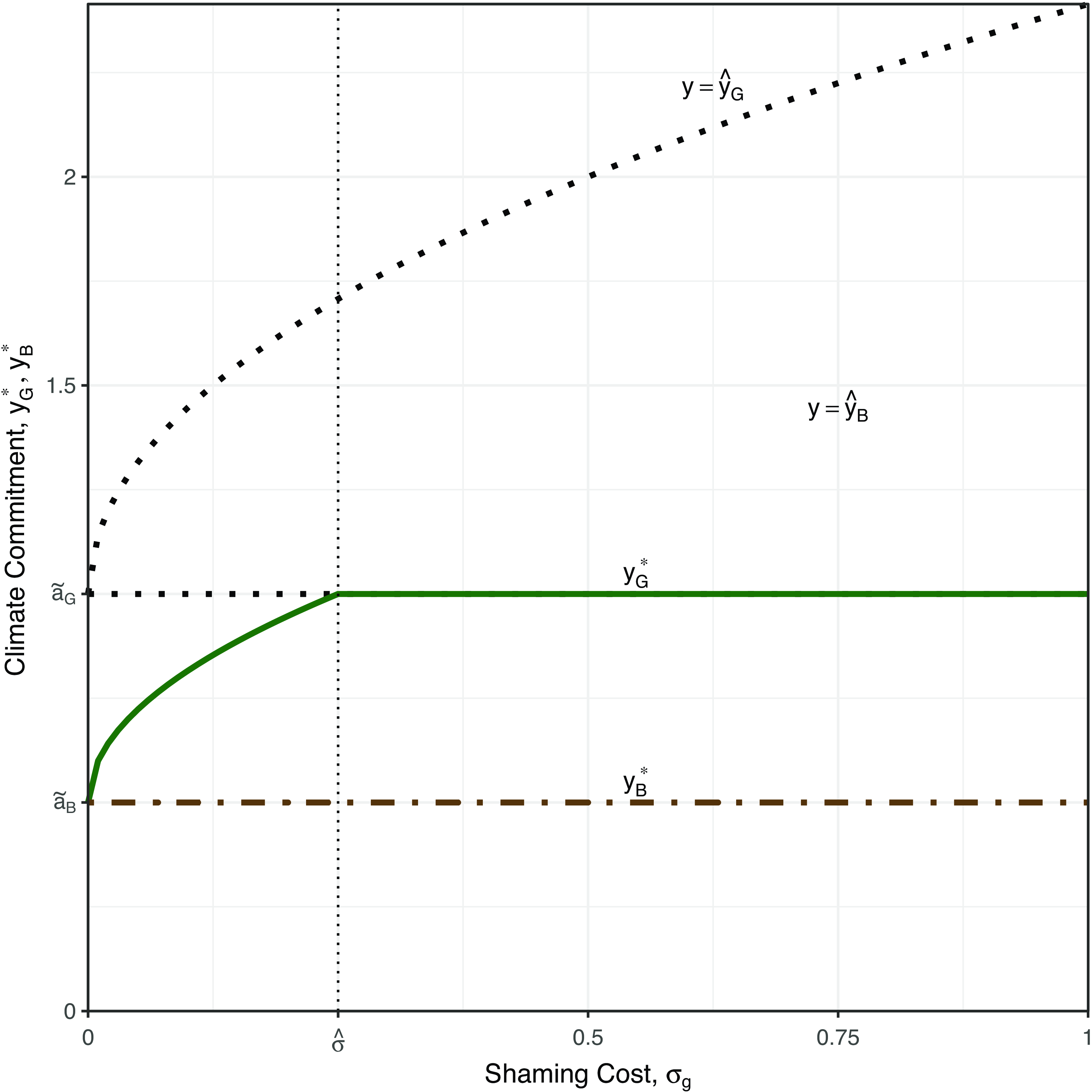

Figure 3 plots the optimal climate commitments given shaming costs

![]() ${\sigma _g}$

, as characterized in Proposition 3. First suppose that shaming costs are large (

${\sigma _g}$

, as characterized in Proposition 3. First suppose that shaming costs are large (

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \ge \hat \sigma $

). By setting the commitment

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \ge \hat \sigma $

). By setting the commitment

![]() $y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}$

at its ideal point, Green can remove any electoral bias in favor of the Brown party and simultaneously commit itself and the Brown party to its ideal point. This is clearly the best-case scenario for the Green party, illustrated as the flat solid-green line on the right-hand side of Figure 3. However, it requires that B’s shaming cost

$y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}$

at its ideal point, Green can remove any electoral bias in favor of the Brown party and simultaneously commit itself and the Brown party to its ideal point. This is clearly the best-case scenario for the Green party, illustrated as the flat solid-green line on the right-hand side of Figure 3. However, it requires that B’s shaming cost

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

is large enough that B would follow through on this commitment.

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

is large enough that B would follow through on this commitment.

Figure 3. Climate commitments and shaming costs for office-seeking parties

As B’s shaming cost falls below the level sufficient to enforce G’s ideal point (

![]() $\bar \sigma \le {\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \le \hat \sigma $

), then G’s optimal commitment becomes less ambitious. G sets

$\bar \sigma \le {\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \le \hat \sigma $

), then G’s optimal commitment becomes less ambitious. G sets

![]() $y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}$

to the highest downstream effort that commits B to compliance with the target, though it is less ambitious than G’s ideal point. This is shown by the curved solid-green segment on the line

$y_{\rm{G}}^{\rm{*}}$

to the highest downstream effort that commits B to compliance with the target, though it is less ambitious than G’s ideal point. This is shown by the curved solid-green segment on the line

![]() $y = {\hat y_{\rm{B}}}$

in the figure. Such a commitment is partially beneficial for G in both policy and electoral terms: the target ties B’s hands to implement a policy closer to G’s ideal point and (as seen in Figure A.2 in the online supplement) partially reduces B’s electoral edge. If B’s shaming costs are even smaller (

$y = {\hat y_{\rm{B}}}$

in the figure. Such a commitment is partially beneficial for G in both policy and electoral terms: the target ties B’s hands to implement a policy closer to G’s ideal point and (as seen in Figure A.2 in the online supplement) partially reduces B’s electoral edge. If B’s shaming costs are even smaller (

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \le \bar \sigma $

), then from an electoral perspective G can do no better than set the commitment to B’s ideal point, which is the flat solid-green line on the left-hand side of the figure. In summary, as shaming costs increase, the Green party can leverage the possibility of being shamed to enforce a more ambitious commitment (although never above its ideal point) while also reducing any electoral bias in B’s favor.

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}} \le \bar \sigma $

), then from an electoral perspective G can do no better than set the commitment to B’s ideal point, which is the flat solid-green line on the left-hand side of the figure. In summary, as shaming costs increase, the Green party can leverage the possibility of being shamed to enforce a more ambitious commitment (although never above its ideal point) while also reducing any electoral bias in B’s favor.

Turning to B’s optimal commitments, the Brown party has an electoral advantage because, ex ante, it would impose lower costs on the median voter to implement downstream climate policies than the Green party would. To retain this edge, the optimal strategy for B entails setting a commitment that would maximally exploit G’s willingness to implement climate reforms by imposing large costs on the median voter if the commitment were to be fulfilled after the election. That is, the Green party is willing to commit to more ambitious pledges, and the Brown party can exploit this by setting a lofty target they do not intend to implement themselves but the Green party would. Counterintuitively, this furthers B’s electoral prospects. The intuition for this result is that, despite being costly for the median voter, the Green party would follow through on the commitment. In particular, if the Green party’s shaming costs are large enough (

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{G}}} \gt \hat \sigma $

), the optimal commitment would be

${\sigma _{\rm{G}}} \gt \hat \sigma $

), the optimal commitment would be

![]() $y_{\rm{B}}^{\rm{*}} = {\hat y_{\rm{G}}}$

, which makes the Green party indifferent between following through and being shamed. This is the curved dot-dashed brown segment on the line

$y_{\rm{B}}^{\rm{*}} = {\hat y_{\rm{G}}}$

, which makes the Green party indifferent between following through and being shamed. This is the curved dot-dashed brown segment on the line

![]() $y = {\hat y_{\rm{G}}}$

in the figure. Obviously, this is not a target that the Brown party would fulfill themselves if elected, but it is B’s optimal strategy because the shaming cost

$y = {\hat y_{\rm{G}}}$

in the figure. Obviously, this is not a target that the Brown party would fulfill themselves if elected, but it is B’s optimal strategy because the shaming cost

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

is small relative to the value of holding office.

${\sigma _{\rm{B}}}$

is small relative to the value of holding office.

Finally, if the Green party’s shaming cost takes moderate values, the Brown party cannot fully exploit the Green party’s willingness to abide by a lofty target. Instead, B’s optimal strategy involves a commitment that zeroes in on the preferences of the median voter. Indeed, if

![]() ${\sigma _{\rm{G}}}$

is moderate, the Brown party commits itself exactly to the median voter’s ideal point

${\sigma _{\rm{G}}}$

is moderate, the Brown party commits itself exactly to the median voter’s ideal point

![]() $y_{\rm{B}}^{\rm{*}} = {\tilde a_{\rm{M}}}$

; this is an electorally popular strategy because the Brown party would offer the policy most preferred by the voter, while the Green party would ultimately implement its own ideal effort, which would be costlier to the voter. This is seen by the flat dot-dashed brown line toward the left of Figure 5. But if the shaming costs are insufficient to motivate the Brown party to implement the median voter’s preferred policies, B picks a target to partially tie its own hands, moving as close as it credibly can toward

$y_{\rm{B}}^{\rm{*}} = {\tilde a_{\rm{M}}}$

; this is an electorally popular strategy because the Brown party would offer the policy most preferred by the voter, while the Green party would ultimately implement its own ideal effort, which would be costlier to the voter. This is seen by the flat dot-dashed brown line toward the left of Figure 5. But if the shaming costs are insufficient to motivate the Brown party to implement the median voter’s preferred policies, B picks a target to partially tie its own hands, moving as close as it credibly can toward

![]() ${\tilde a_{\rm{M}}}$

, seen by the increasing dot-dashed brown line on the left of the figure. In summary, at low-to-moderate shaming costs, the Brown party will increase its commitment by moving toward the preferences of the median voter. However, when shaming costs are high enough, Brown has a dominant electoral strategy to commit to a pledge that it will paradoxically never implement but the Green party will; and despite the downstream shaming, this enhances Brown’s electoral odds.

${\tilde a_{\rm{M}}}$

, seen by the increasing dot-dashed brown line on the left of the figure. In summary, at low-to-moderate shaming costs, the Brown party will increase its commitment by moving toward the preferences of the median voter. However, when shaming costs are high enough, Brown has a dominant electoral strategy to commit to a pledge that it will paradoxically never implement but the Green party will; and despite the downstream shaming, this enhances Brown’s electoral odds.

Propositions 2 and 3 demonstrate that commitments are always weakly increasing in the cost of being shamed,

![]() ${\sigma _g}$

. As internationally imposed shaming costs for failing to meet national targets increase, leaders are willing to make greater efforts to meet such targets and therefore avoid being shamed. Note that this intuition does not rely on the parties being shamed at the same level, or shaming costs being uniform by party. For example, if the Brown party paid scant attention to their international reputation, then the Green party could do little to tie the Brown party’s hands. By contrast, the counterintuitive result that the Brown party can set a lofty climate target that it does not intend to meet and yet still increase its electoral odds is further strengthened if the Green party faces higher shaming costs. Indeed, the Brown party would choose targets of increasing ambition, which the Green party would comply with to avoid being shamed.

${\sigma _g}$