Introduction

This article documents socio-cultural and environmental changes to a body of southern Italian folkloric texts – as used in practice over the last three decades – in order to provide insight into the dynamics of contemporary life in southern Italy and the changing relationship between people and the land documented in existing research (e.g. Bevilacqua Reference Bevilacqua1998 and Reference Bevilacqua2002; Quaranta et al. Reference Quaranta, Salvia, Salvati, De Paola, Coluzzi, Imbrenda and Simoniello2020). Changes in society are reflected in the language used in everyday life. In Italian, for example, expressions such as comunità virtuale (‘virtual community’) and video virale (‘viral video’) no longer require any explanation, suggesting broad social and cultural shifts. Such shifts can also be reflected in ‘verbal folklore’ which refers to structured information passed down in words, including proverbs, sayings, stories, prayers, formulae, recipes, and other texts that are preserved, practised, propagated, and may be modified over time. The compound term ‘folklore’ stands for the ‘lore’ of the ‘people’, as intended by William John Thoms who coined the term (Boyer Reference Boyer1997), ‘lore’ referring to common knowledge of a traditional nature where the word ‘traditional’ is understood to refer to the folkloric item being repeated and consequently propagated over a period of time (Bronner Reference Bronner2016, 15).

As observed in the case of rituals (Clemente and Mugnaini Reference Clemente and Mugnaini2001, 116), if we consider folklore in the context of the point in time in which it is repeated, we can begin to understand folklore as a historical process. Thus, folkloric texts can be used as historical points of reference (see also Teti Reference Teti, Teti and Plastino1990, 21–22 and 235). They often also refer to objects or events tied to a specific point in time. For example, the southern Italian folkloric texts of the Cento Croci (‘One Hundred Crosses’) have been traced back to the time of the First Crusade (Luciani Reference Luciani2017). However, folklore is not static. Like ‘lived religion’ and ‘tradition’ (Orsi Reference Orsi and Hall1997, 7–8), it is always ‘invented’ in the sense of being dynamic, subject to change and to multiple influences (Hobsbawm and Ranger Reference Hobsbawm and Ranger1983, 1–7). As Eric Hobsbawm (Reference Hobsbawm and Ranger1983, 2) states, ‘“Custom” cannot afford to be invariant, because even in “traditional” societies life is not so’. Consequently, folklore as an expression of a fundamental social process must also change in practice.

In southern Italy, significant social, cultural, and environmental shifts have occurred especially over the last three decades. Rural demographics and landscapes have undergone observable transformations (Bevilacqua Reference Bevilacqua1998 and Reference Bevilacqua2002; Barbera Reference Barbera and Agnoletti2013; Ricca and Guagliardi Reference Ricca and Guagliardi2015; Rizzo Reference Rizzo2016; Quaranta et al. Reference Quaranta, Salvia, Salvati, De Paola, Coluzzi, Imbrenda and Simoniello2020). Coastal urbanisation, change in land use, migration from the country to the city, influx of foreign labour to fill the resulting vacuum in agriculture (Corrado and D'Agostino Reference Corrado, D'Agostino, Kordel, Weidinger and Jelen2018, 281–82), the restructuring of agriculture to give the most control to the largest companies in the sector (D'Onofrio Reference D'Onofrio2020, 54–60), and technological advancement as part of the modern living environment have impacted landscapes and lifestyles. Consequently, bearing in mind Hobsbawm and Ranger's concept of ‘the invention of tradition’, this study demonstrates that as southern Italian landscapes and lifestyles have changed, so has the corresponding verbal folklore adapted, and that an analysis of folkloric texts provides important clues about the daily life and outlook of southern Italians.

My approach is also informed by Alessandro Portelli's finding concerning perceived errors in transmission of oral narratives (Portelli Reference Portelli and Bermani2001, 61–2 and Reference Portelli, Perks and Thomson2016, 52–4). Portelli demonstrates that deviations from the expected narrative are not errors, but modifications which reflect the changing knowledge and perceptions of the times (e.g. Portelli Reference Portelli, Perks and Thomson2016, 54). Additionally, fundamental human needs also impact the choice of folklore that people pass down. For example, perceived shortages (e.g. water, food, shelter, etc.), within a specific regional, cultural, or environmental context, lead to an emphasis on the verbal folklore that addresses the object of those shortages (e.g. Luciani Reference Luciani, Cox, Hamilton, McLardy, Pettman and Stewart2015 and Reference Luciani2017). There is, therefore, a correlation between changes in verbal folklore and changes in society and the environment, which this article traces by examining modifications to southern Italian folkloric texts over the last three decades.

The data examined here comprises folkloric texts as repeated in the everyday lives of southern Italians – including sayings, proverbs, prayers, textual charms, stories, home remedies, and traditional recipes collected from the 1990s onwards. Although my verbal folklore collection includes texts from various southern Italian regions, such as Sicily, Calabria, Apulia, and Campania, this article focuses on material from the southern Italian region of Calabria. My corpus started as a community folklore preservation project and evolved to include a record of variations over time. My informants, comprising approximately 80 southern Italians, aged between 18 and 85 years at the time of collection, include relatives, friends, and acquaintances (both first- and second-hand) with varied backgrounds, professions, and levels of education. A rigorous approach to the collection, clarification, and contextualisation of data is fundamental to this study. This approach minimised errors by reading the transcription back to the informant(s) and querying the informant(s) concerning the meaning and intent carried by the folkloric text in question. Details were considered crucial, especially elaboration on elements which were ambiguous or not obvious in the text. Thus, iterative consultation with informant(s) was pivotal to the process.

Reflections of events and of changing conditions in southern Italian verbal folklore

Some of the most significant changes to our living environment are the product of technological advancement. This process has engendered major social and cultural shifts, especially via the introduction of ‘virtual’ communities and a variety of electronic devices (Miller Reference Miller2011; Magaudda Reference Magaudda2014a, 59 and Reference Magaudda2014b, 430–32; Aroldi Reference Aroldi2015, 4 and 6–7). According to ISTAT (Italian National Institute of Statistics 2019, 226250), information and communication technologies have become widespread throughout Italy, with 73.7 per cent of Italian households accessing the internet, especially via smartphones (89.2 per cent). A study conducted in 2017 (Zucco et al. Reference Zucco, Lavano, Anfosso, Bianco, Pileggi and Pavia2018, 132–4), in the Calabrian geographical area of Catanzaro, found that, among a sample of 1,355 parents of public school students, 96.9 per cent of respondents use the internet, with 84.9 per cent of parents using social media, especially Facebook (98.7 per cent).

Social media also impacts verbal folklore. Alongside the opportunity to reach a wider and more diverse audience, as in the case of advertising using the mass media (see Mieder and Mieder Reference Mieder and Mieder1977), posts have to fit with a predefined structure which revolves around a simplified and graphical presentation (Nicolescu Reference Nicolescu2016, 62–8). Thus, on Facebook, folkloric texts such as proverbs, maxims, stories, jokes, and traditional recipes are more effectively shared in simple, standard language and in combination with visual aids such as pictures (for example, see Figure 1). However, traditional recipes tend to be presented using different ingredients, procedures, and tools based on what is currently available on the market (e.g. the change from ricotta to custard and from dowels made of canna, Arundo donax, to stainless steel dowels for the Sicilian cannoli), while jokes and stories are often abbreviated in order to focus on a perceived main point assumed to be understandable to a larger audience.

Figure 1. An example of modified folkloric text presented with fan art shared on Facebook by several southern Italians – aged between 20 and 70 years – during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020. The Italian sentence reads: ‘So long as there is coffee there is hope. Good morning’. This is derived from the Italian proverb Finché c’è vita c’è speranza (‘So long as there is life there is hope’).

The Calabrian story I called Maria, Giuseppe e l'asinello (‘Mary, Joseph, and the little donkey’) provides a good illustration of such phenomena. This is the story from which the Calabrian saying Il mondo non l'ha accontentato neppure il Signore (‘The world couldn't even be pleased by the Lord’) originated.

According to two of my Calabrian informants – both middle-aged males who recounted the story respectively in standard Italian and in dialect during the 1990s – this story comprises five main scenes: 1) Mary on the donkey, Joseph on foot, and bystanders deriding them because the donkey was not being used by the elder of the two; 2) Joseph on the donkey, Mary on foot, and bystanders deriding them because the donkey was not being used by the woman; 3) Both Mary and Joseph leading the donkey on foot with bystanders deriding them for not putting the donkey to good use; 4) Both Mary and Joseph on the donkey with bystanders deriding them for overloading the ‘little’ donkey; 5) Both Mary and Joseph carrying the donkey on their shoulders with bystanders deriding them for overburdening themselves, and then the bystanders becoming overwhelmed with mirth when the donkey falls to the ground and dies from its injuries.

My Calabrian informants explained that the moral of this story was ‘You cannot please everyone’. However, in 2018, this story appeared on Facebook with the heading La gente avrà sempre qualcosa da dire (‘People will always have something to say’). This heading was followed by a comic strip which illustrated only the first four scenes from the story without any contextualisation. Furthermore, in the post, there was no indication of who exactly was being illustrated, although associations could still be made with Mary and Joseph based on the costumes used in the comic strip.

Upon inquiry about the source and the content of the post, two young southern Italian females who shared it pointed out that it was derived from a recently published book; that the protagonists were a man and a younger woman who represented all those who worried about what people say; and that the moral of the story was simply: ‘Do what you want to do’ – implying that the man and the woman in the comic strip were not, and suggesting a shift of emphasis from an awareness of others to a more solipsistic outlook. Moreover, a clear connection can be made between the Calabrian version of the story and the non-religious fable often titled The miller, his son, and the donkey of which there are many eastern and European versions (Uther Reference Uther2004). Thus, we can trace the evolution of the story from a non-religious fable to an explicitly Christian story (or possibly vice versa) and, finally, based on the version published on Facebook, an abbreviated and more general version that could be interpreted as being religious or non-religious, depending on who was associated with the young woman and the older man.

This cultural dilution is not only to be observed in the context of mass communication technology, but can also be found at a local level, where specific cultural references can be readily understood. Local-level changes to folkloric texts also demonstrate a general decline in reliance on ‘tradition’, in the sense of how things used to be done or perceived, due to changes in the people's immediate living environment. To illustrate this, in the 1990s, two elderly couples from the Calabrian town of Stefanaconi told me a popular story, in dialect, concerning a man who was travelling on foot to the festival of the Madonna of Monserrato, in the inland Calabrian town of Vallelonga. Along the way, the man was asked by three different people to obtain for them a flageolet (a type of flute), using the specific word from each of the people's dialects. In 2005, 2008 and, again, in 2017, I heard the same story recounted by three different Calabrian informants – all males over the age of 40 – during social gatherings in coastal areas within the same province. However, each time, not only was the story reduced and recounted in standard Italian, but the flageolets were also replaced with different instruments and the story was stripped of locally specific information. The popular festival in honour of the Madonna of Monserrato became just ‘a festival’ and the varied dialect references to the flageolets – which were once locally produced – were replaced by references to other musical instruments, such as the ‘whistle’ and the ‘harmonica’. This replacement, together with the loss of dialect vocabulary for flageolets, followed the decline in the manufacturing and sale of those instruments at local festivals. Thus, the reduction in the availability of particular items leads to the disappearance of those references from the corresponding folkloric texts, with profound changes in the meaning and utility of those texts.

Such modifications to verbal folklore due to changes in people's living environment also occur in relation to the geographical location of the people concerned. For instance, while earthquakes are common in Italy, they do not occur everywhere. It is not surprising, therefore, that folkloric texts concerning earthquakes are found where earthquakes occur and are generally not maintained in places where earthquakes do not occur. Furthermore, such texts are modified in practice according to what is present in the people's immediate living environment. To illustrate this point, in seismically active environments located near the sea or a river and especially where the patron saint is Saint Peter the Apostle, the fisherman, folkloric texts mention Saint Peter in connection with storms, flash floods, seaquakes and earthquakes. Conversely, in similar environments that are not seismically active, Saint Peter is mentioned only in relation to storms and floods (e.g. Sordi Reference Sordi1997, 89). Thus, in the 1990s, in San Pietro di Vibo Marina, along the Tyrrhenian Coast of Calabria – where people have constant reminders of natural disasters which have also modified the landscape (see Figures 2–3) – a retired couple, caretakers of the local church dedicated to Saint Peter, introduced me to an old prayer which had migrated from dialect to standard Italian as follows:

Figure 2. The island of Stromboli, a back-arc volcano which is still active (see Sartori Reference Sartori2003), as seen from the Tyrrhenian Coast of Calabria, within the province of Vibo Valentia. Photograph by the author (19 December 2005).

Figure 3. A section of the Calabrian Tyrrhenian Coast with the Port of Vibo Marina, the town of Bivona, and the village of San Pietro of Vibo Marina only four kilometres away from the port, where the landscape has been altered by natural processes which are often disastrous. In this case, part of the Apennine mountainside slumps towards the coast as per the process described by Piero Bevilacqua (Reference Bevilacqua1998, 32). Photograph by the author (18 December 2005).

Three younger informants – from a Calabrian town whose patron saint was not Saint Peter – subsequently reduced this prayer to the last two lines only, suggesting a loss of religious specificity. However, despite this loss, the maintenance of the last two lines also suggests a long-lasting impact of recurring natural disasters within the geographical environment in question (see also Teti Reference Teti, Bertolaso, Boschi, Guidoboni and Valensise2008).Footnote 2 Furthermore, according to my original informants, this prayer was derived from a rather long hymn in which Saint Peter was invoked on a variety of issues. In fact, in Ardore Marina, on the Ionian Coast of Calabria, Luigi Schirripa (Reference Schirripa2000, 253–54) reports a longer version of the prayer above, as follows:

The shorter version – also reported by Schirripa in dialect (Reference Schirripa2000, 279) – drops the last two lines because war, plague, famine, and drought had not recently occurred in Calabria. This demonstrates a relationship between events and verbal folklore, in which verbal folklore changes for very practical reasons in response to contemporaneous events. In fact, the recent COVID-19 pandemic and its association with the plague as contagious disease has seen the reintroduction of older references to the plague drawn from older folkloric texts. This revival has been conspicuously apparent on Facebook, where folkloric texts often appear in posts. A popular example, in this context, was an old Sicilian prayer in which the Virgin Mary is invoked against the plague – widely shared on Facebook following its publication on ragusanews.com (08 March 2020).

The relationship between verbal folklore and what people experience in their living environment becomes particularly evident in light of the maintenance, propagation, and modification of a body of folkloric texts which mention Saint Barbara against thunder and lightning. In the 1990s, two female informants, both over the age of 50 and from the Calabrian province of Vibo Valentia, recited this particular prayer derived from hymns narrating events in the life of Saint Barbara (compare Meli Reference Meli2000, 135–6; Tassone Reference Tassone2012, 81–2):

This prayer can be described as a textual charm because it is meant to dispel the fear of thunder and lightning following Saint Barbara's example. In this version in dialect, the fear of thunder and lightning is emphasised by the line nta nu chianu sula stacìa (‘[she] was on a plain all on her own’). Nu chianu (‘a plain’), in the sense of an open field, is one of the most dangerous outdoor locations with respect to lightning strikes, thus emphasising the faith and courage of Saint Barbara. However, in autumn 2005, the same informants, who had relocated from the countryside to a coastal town, while reciting the charm indoors, replaced the expression nta nu chianu (‘on a plain’) with nta na cammara or, in standard Italian, in una camera (‘in a room’). This replacement illustrates the impact that people's location has on the verbal folklore they pass down. It also reflects the modern tendency of southern Italians to lead a more sheltered urban life away from direct contact with the land (Bevilacqua Reference Bevilacqua1998, 31–5; Rizzo Reference Rizzo2016, 236–40). This tendency became especially evident when my informants, while reciting the charm outdoors, dropped the line in question completely. Furthermore, in 2019, another female informant over the age of 50 but from the Apulian city of Taranto, recited the following version, in standard Italian:

In this version, which according to my informant was originally in dialect from the Sicilian city of Messina (see also Tassone Reference Tassone2012, 82), Saint Barbara's location is completely left out. The omission of the saint's location (i.e. on a rock in an open field used for grazing), as presented in earlier versions of the charm and hymns (e.g. Tassone Reference Tassone2012, 81–2), seems to indicate that the outdoor setting has lost relevance, which, once again, is suggestive of the modern tendency to lead a more sheltered urban life and, by extension, of a loss of contact with some aspects of the outdoors.

Thus, the examples analysed so far demonstrate a tendency to maintain folkloric texts which are still relevant to the people concerned while modifying them according to what is applicable in the contemporary context. This tendency emerges as a consequence of a broader pattern of migration towards the coast, which depopulates inland rural areas while urbanising coastal rural areas (Rizzo Reference Rizzo2016). The depopulation of inland rural areas on the part of southern Italians suggests a growing distance from the land as evidenced by increasing foreign labour in agriculture (Nicolosi, Cambareri and Strazzulla Reference Nicolosi, Cambareri and Strazzulla2009, 6; Corrado and D'Agostino Reference Corrado, D'Agostino, Kordel, Weidinger and Jelen2018, 281). In fact, some modifications to folkloric texts indicate the southern Italian tendency to lead a more sheltered urban life as well as disappearing connections with some aspects of the natural environment.

Losing touch with the natural environment: impact on perspective

Disappearing connections with some aspects of the outdoors can be evidenced by the transformation of southern Italian folkloric narrations set in the outdoors, particularly those concerning unusual occurrences, such as people struck by lightning in open fields, the apparition of faces on tree trunks, ghost sightings at particular outdoor locations, and treasures buried in the countryside.

In current versions of these stories, the outdoor settings tend to be portrayed in an almost idealised manner with a focus on the natural beauty, comfort and ease one is presumed to feel in such places. This romanticised version of the natural world suggests a lack of direct experience and a loss of familiarity with its more dangerous and uncomfortable aspects, as corroborated by the loss of detailed descriptions of the natural settings in these particular texts.

For example, the Strait of Messina is often described as picturesque and ‘unique’, a fascinating realm of the ‘Fata Morgana’ (Morgan the Fay), associated with the legend of Scylla and Charybdis and the miracle of the fifteenth-century Calabrian saint, Saint Francis of Paola (e.g. Mazzeo Reference Mazzeo2007). In reality, the Strait of Messina is a rather dangerous part of the Mediterranean. Aside from being of high seismic activity, it hosts strong tidal currents which create a unique marine ecosystem (Spanò Reference Spanò1998). In addition to this, near the Calabrian town of Scilla (Scylla), there is a natural and dangerous whirlpool; and, in looking at Sicily from Calabria and vice versa, one can often observe the so-called ‘Fata Morgana’, a dynamic mirage due to a thermal inversion whereby ‘castles’ and land forms appear in a narrow band just above the horizon (Mirisola Reference Mirisola2016).

The hazards caused by such phenomena were well known to fishermen from Pizzo Calabro who, in the 1990s, often sang hymns to Saint Francis of Paola, patron of seafarers, asking for the saint's assistance while narrating his miracles against the perils that occur at sea (Meli Reference Meli2000, 156). Although Pizzo Calabro is not on the Strait of Messina, it is a maritime town of seafarers who would have had to brave the perils of the strait. Moreover, up to 1963, Pizzo Calabro hosted fixed tuna-fishing plants connected with the local Convent of the Minim Friars, Saint Francis of Paola (Meli Reference Meli2000, 154–5). However, in 2013, during the annual Festa della Gente di Mare (Festival of Seafarers), involving both Calabrian and Sicilian coastal towns and parishes (i.e. Vibo Marina, Tropea, Pizzo Calabro, Francavilla Angitola, Benincasa di Vietri sul Mare, and Milazzo) and including different groups of people – such as priests, representatives of the Minim friars, the seafarers’ committee, the coastguard, the harbour office, and many pilgrims of different backgrounds – the focal point was just a particular version of the folkloric story entitled La traversata dello stretto sul mantello (‘The crossing of the strait on the cloak’) which can be translated as follows.

Saint Francis and his fellow friars stopped on the Tyrrhenian Coast of Calabria on their way to Sicily. Needing to cross the Strait of Messina, he asked a number of seafarers for passage while openly admitting that he and his fellow friars had no money. ‘Here, with no money, you cannot sail’, replied the seafarers. In response, Saint Francis spread his cloak upon the Tyrrhenian Sea of Calabria and, stepping onto it, raised one end with his walking stick and set sail. Thus, he took himself and his fellow friars safely across the strait to Sicily.

This version of the story makes no mention of the natural harshness and hazards of the strait as described in earlier versions and in the hymns derived from the story (compare Meli Reference Meli2000, 156). The omission of such key aspects of the natural environment reflects a shift of focus away from its natural harshness and the dangers involved in crossing the strait. This shift can be explained by the fact that the majority of the people crossing the strait today do so in the comfort of ferries and other modern vessels. Furthermore, the closure of local tuna-fishing plants, due to modern vessels equipped to hunt and catch tuna before it reaches the coast (Esposito Reference Esposito2020), has contributed to succeeding generations migrating out of the corresponding primary industry and into secondary and tertiary industries.

Similar transformations of folkloric texts pertaining to farming and cultivation also demonstrate a shift of outlook due to modern lifestyles increasingly removed from the natural world.

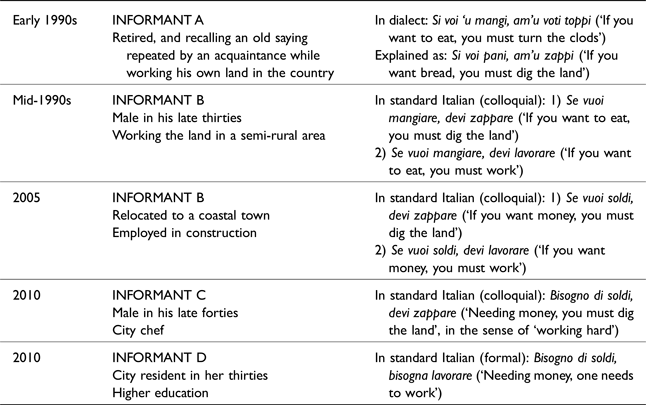

The table below illustrates a progression of changes to a Calabrian version of the standard Italian proverb Chi non lavora non mangia (‘He who does not work will not eat’) based on a line from the Second Letter of Paul to the Thessalonians (3:10): ‘Anyone unwilling to work should not eat’. This progression takes us from a concrete statement referencing the specifics of digging the land to a softer, more generic idea of work.

The changes to the saying above demonstrate two key shifts: from working the land to working in a general sense and from a general awareness of how to fulfil one's basic needs directly from the natural environment to a focus on the means by which those needs are met (i.e. money). Looking at the informants in order, informants A and B were involved in family farming, which has undergone significant transformations since the 1990s, especially due to the ageing of the family members who ran the farm, falling returns, and de-familiarisation of the farm itself (Corrado and D'Agostino Reference Corrado, D'Agostino, Kordel, Weidinger and Jelen2018, 274). However, informant A had been involved in wheat and flour production while informant B was involved in other forms of agriculture, which explains the modification to the saying from informant A's ‘If you want bread’ to informant B's ‘If you want to eat’. Furthermore, we see, once again, the migration of succeeding southern Italian generations out of the corresponding primary industry and into secondary and tertiary industries hosted in larger urban areas. Some of the mechanisms behind this migration are local in nature, as documented in existing research (D'Onofrio Reference D'Onofrio2020; Corrado and D'Agostino Reference Corrado, D'Agostino, Kordel, Weidinger and Jelen2018, 273–5). Succeeding generations with a high level of education tend to migrate away from rural areas, rejecting employment in agriculture ‘due to low wages, low skills, irregularity, long, hard working hours and [low] social status’ (Corrado and D'Agostino Reference Corrado, D'Agostino, Kordel, Weidinger and Jelen2018, 274).

Migration from the country to urban areas underlines the shift of emphasis from ‘ends’ (e.g. food, water, shelter, etc.) to ‘means’ (e.g. money, cars, mobile phones, etc.), which corresponds to a growing distance from the natural environment and is suggestive of increased commercial dependence. For example, in the 1990s, many Calabrian communities – both in coastal and inland areas within the provinces of Catanzaro, Vibo Valentia, and Reggio Calabria – still implemented a variety of traditional recipes using materials and ingredients collected from the natural environment. These community practices, based on knowledge carried by verbal folklore, included the making of different types of bread (e.g. bread made with corn flour, elderberry flowers, and levàtu, fresh yeast made with coarse wheat flour left to ferment in double the volume of warm water), tomato sauce, conserves (especially those made with an assortment of vegetables, olives, and non-cultivated mushrooms), wine, natural remedies for minor ailments along with a variety of natural soaps and disinfectants/sanitisers (e.g. based on lemon, home-made vinegar, and the juice from the leaves of aspraggine mascolina, Picris hieracioides). Thus, within the territory of the coastal town of Bivona, vineyard and olive-grove proprietors used to invite the locals for wine making and for the grape or olive harvest, sharing folkloric texts relating to these activities as well as making vinegar and natural soaps with low-grade olive oil and rosemary. On the opposite side of Calabria, in the inland town of Serra San Bruno, during the mushroom season, different groups of people used to meet to go to the woods to gather non-cultivated mushrooms. Along the way, the most experienced people of each group (e.g. secondary-school teachers, horticulturists, local guides, etc.) often shared folkloric texts pertaining to the following. 1) Finding one's way through the woods (e.g. In questa stagione il sole a mezzogiorno è a meridione, ‘In this season, the sun at midday is in the south’). 2) First-aid (e.g. Aspraggine appiccicosa da rotolare fra le palme e da spremere sulla ferita, ‘Sticky Picris to be rolled between your palms and squeezed on the wound’). 3) Identifying non-toxic mushrooms based on appearance, scent, texture, and location (e.g. Lontano dai funghi di Biancaneve, ‘Far from the mushrooms of Snow White’, i.e. mushrooms of the Amanita family). 4) Optimum ways for gathering, carrying, storing, and preparing the mushrooms collected (e.g. A fettine rosolate con erbe di bosco profumate, ‘In browned slices [i.e. in the frying pan] with fragrant herbs of the woods’). Ten years later, in the same Calabrian communities, such folkloric practices had declined, due especially to the migration of younger generations into secondary and tertiary industries of larger urban centres and the monopolisation of agro-food production by large corporations (D'Onofrio Reference D'Onofrio2020, 54–7), which contributed to the force of other processes driving the dependence on money. However, the practices in question based on folkloric texts and directly related to the natural environment illustrate the role of verbal folklore as a social mechanism, irrespective of background, whereby much of the information that it carries depends heavily on it being applied. When it can no longer be applied due to changes in both lifestyle and the environment, it is either modified to fit the new context or effectively forgotten, as we shall see in the next section.

Socioeconomic change and the utility of verbal folklore in tracing forgotten knowledge

Changes to folkloric texts relating to the natural environment not only reflect the tendency to lead a more sheltered urban life, but can also be connected with material changes within the natural environment in question. In exploring this connection, we can examine changes to folkloric texts related to some socioeconomic shifts. In this context, the most concrete examples revolve around material changes in Italy, especially changes in landscape (Agnoletti Reference Agnoletti2013; Ricca and Guagliardi Reference Ricca and Guagliardi2015).

On the Tyrrhenian side of Calabria – within the territory of Vibo Valentia, Pizzo Calabro, Longobardi, Vibo Marina, and Bivona – the availability of land for agricultural purposes is steadily shrinking as metropolitan and residential development encroaches on what was once productive farmland (Costa et al. Reference Costa, Sturiale, Passarelli, Salamone, Camarda and Grassini2001, 295–8; Ietto, Salvo and Cantasano Reference Ietto, Salvo and Cantasano2014, 340–2). Although laws for the conservation of rural landscapes are now in place (Agnoletti Reference Agnoletti2013, 4), burgeoning urbanisation, in Calabria and elsewhere in Italy, has brought about a significant loss of polyculture, terraced farming, and the region's once extraordinary biodiversity (Barbera Reference Barbera and Agnoletti2013, 490). As a consequence, aside from the fact that many non-cultivated plants have become rare (e.g. Teti Reference Teti2002, 178), the space for agriculture is shrinking and along with it the range of agricultural practices. Crops which require more space either for management or viability can no longer fit in the smaller areas available for farming. In fact, the geographical area in question has been classified as presenting ‘Rural areas with development problems’ (Agnoletti Reference Agnoletti2013, 18). All this is most typically exemplified by a shift away from the production of wheat (INEA [Innovation and Networks Executive Agency] 2013, 5).

Folkloric texts reflect these changes and those relating to wheat production tend to be replaced by less specific variations of the same. For example, in the 1990s, some of my older informants, in this geographical area, recalled the practice carried by verbal folklore as follows: Quandu passan'i groi è tempu ‘i siminar'u ranu (‘When migrating cranes fly past, it is time to sow wheat’). By 2005, the informants I was interviewing from the same location were now working smaller parcels of land for which wheat production is not viable. These later informants replaced the proverb above with the following: Per San Leonardu simina chè tardu (‘By Saint Leonard's [6 November], it is late to sow’). Not only is this latter proverb not based on the observation of nature, but it is also quite general and could apply to the sowing of a number of plants other than wheat (e.g. Brassica rapa, broccoli, etc.). If my informants no longer feel compelled to produce wheat, the former proverb no longer holds relevance for them and consequently it is dropped.

By contrast, the increased focus on olive production encouraged by the Olive Regional Plan aimed at supporting investment in the corresponding industry (Nicolosi, Cambareri and Strazzulla Reference Nicolosi, Cambareri and Strazzulla2009, 5; INEA 2013, 5) has motivated the same informants to cultivate olive trees, which makes the sayings and traditions specific to olive tree cultivation and many olive preparation recipes hold greater relevance. Thus, a proverb I was first introduced to in the late 1990s, in standard Italian, Per Santa Reparata ogni oliva è olivata (‘By Saint Reparata's [8 October] every olive has grown to its full size’), has been carried unchanged or sometimes modified as Ottobre a poca strada ha ogni oliva olivata (‘October on its way means every olive has grown to its full size’), to further aid memory recall as explained by my informants, because this proverb is relevant to the people concerned (as a reminder to prepare for harvesting olives). However, even folkloric texts which have kept their relevance are not immune to the impact of other material developments, such as the changes in landscape and those brought about by technological progress. The shift away from wheat production and the introduction of more efficient ways to harvest olives have opened up the time slot spanning October and November for the pruning of olive trees. The pruning used to be carried out in January because, during October and November, in addition to the harvesting of olives, there was a greater compulsion to prepare the land for sowing wheat. Thus, the old saying still repeated in the 1990s, in dialect, A jennaru puta paru (‘In January, prune everything’, suggesting the presence of a variety of plants) is now modified, in standard Italian, as follows: Si può anche potare dopo le feste di Natale (‘The pruning can also be done after the Christmas season’) – to which my informants who cultivate olive trees often add that it is better for olive trees to be pruned in autumn (i.e. November). Thus folkloric texts illustrate how cultural shifts tend to be driven by physical changes in the people's living environment, including landscape.

Modifications to folkloric texts reflecting changes in landscape and vegetation also denote a loss of specific knowledge concerning raw materials that gradually lose relevance and become increasingly unfamiliar. This loss is especially evident with respect to particular non-cultivated plants. Although information relating to such plants can now be easily accessed via the internet, in practice, many people are no longer able to identify those plants because they lack important physical, sensorial experience revolving around the plants in question. In fact, it has been observed that physicality is an important part of the way people identify with cultural elements (Magaudda Reference Magaudda2014b, 433). Despite the fact that the internet can provide descriptions of an object, including visual aids such as pictures, only when people can experience a sensorial connection with objects, via all of their senses – the sense of touch being the most powerful and that of smell the most faithful in terms of memory (O'Donohue Reference O'Donohue1997, 95 and 102) – are they able to construct meanings and memories as part of their culture. Consequently, verbal folklore that does not depend heavily on physical, sensorial experience (i.e. on objects in the real world), such as humorous or moral folkloric texts (Nicolescu Reference Nicolescu2016, 62–7), can be propagated effectively even online because its benefits rest on a psychological level. Conversely, folkloric texts pertaining to objects in the natural world are propagated less effectively because they require commonly held points of reference within the people's living environment. These points of reference depend heavily on the physical, sensorial experience of the objects in question because language alone is inadequate to carry the necessary detail.

To illustrate this, in the Calabrian province of Vibo Valentia, the difference between wild pears and cultivated pears was once common knowledge, as evidenced by the following abbreviated proverb, in dialect: A'grappidaru non po’ fari pira, faci agrappidi (‘A wild pear tree cannot produce common pears, it produces wild pears’). In the second half of the 1990s, several male and female informants from the same province initially described the agrappidaru (‘wild pear tree’, literally ‘tree of small sour pears’), in standard Italian, as a pianta selvatica (‘wild plant’) and, more recently, as un albero che faceva fiori (‘a tree that would flower’, i.e. in the past tense), making no mention of wild pears. Aside from the fact that, by the late 1990s, wild pear trees were scarce, standard Italian does not possess the terminology necessary to distinguish the wild pear from the cultivated pear. Thus, the shift towards the simplified diction of standard Italian (e.g. pero selvatico, ‘wild pear tree’) conflates the terminology and consequently confuses the user as to the meaning of the term. This linguistic decay in meaning results in a saying that does not make much sense in standard Italian (Il pero selvatico non può fare pere, ‘A wild pear tree cannot produce pears’). Consequently, by the late 1990s, the same informants replaced the word agrappidaru with perzicara (‘peach tree’), modifying the proverb in question as follows: A perzicara non po’ fari pira, easily translated into standard Italian as Il pesco non può fare pere (‘A peach tree cannot produce pears’). What we can see here is the replacement of an unfamiliar plant with a familiar one. However, during this process, the intention of the older version of the proverb (that to produce sweeter pears, a wild pear tree needs grafting) is lost. The older proverb comes to be replaced by a proverb which carries much the same meaning as the English saying ‘You cannot get blood from a stone’. This example of linguistic decay is rather revealing of one of the processes by which culture changes.

The lack of physical, sensorial experience of specific wild plants also impacts medically relevant folkloric texts. For instance, in the 1990s in the Calabrian town of Vibo Marina, a group of vendors and their customers often repeated the folkloric sayings Ciquita pel diabete (‘Crepis for diabetes’ – i.e. Crepis vesicaria, to be distinguished from the Crepis lacera which is toxic) and Aspraina femminina: erba brutta, ma buona (‘Picris echioides: ugly but beneficial herb’). By 2006, these sayings had been modified respectively as Cicoria pel diabete (‘Chicory for diabetes’ – where chicory is not as bitter as the Crepis vesicaria and not as effective for diabetes) and Radicchina: erba brutta, ma buona (‘Small radicchio: ugly but beneficial herb’). This reflected the fact that wild plants such as Crepis vesicaria and Picris echioides, were no longer available at local markets or at the greengrocer's. This suggests that suppliers of local produce, including primary producers, may have also lost touch with particular wild plants. Part of the problem in this case is that big supermarket chains now dictate what is produced, where it is produced, who produces it, and at what price (D'Onofrio Reference D'Onofrio2020, 56). This control, in turn, impacts the verbal folklore that addresses the people's dietary needs, as also evidenced by the simplification of traditional vegetable dishes which, in the past, included a variety of non-cultivated plants (Guarrera and Savo Reference Guarrera and Savo2016, 212).

Despite these changes, there are cases where folkloric texts retain important medical knowledge. These cases often include home remedies. However, home remedies which depend on the use of specific wild plants tend to be dropped when either the plant itself can no longer be found or when the knowledge necessary to identify the plant has been lost – usually due to a lack of familiarity that results from either the plant becoming rarer or having fallen into disuse when better alternatives are available (for example over-the-counter medicines such as anti-inflammatories and analgesics). For instance, the use of wild verbena (verbena officinalis), employed in the past as an anti-inflammatory and also considered suitable for treating eye problems (e.g. inflammation, ruptured blood vessels, and so on), was transmitted by Sicilian and Calabrian textual charms (for some examples, see Lombardi Satriani Reference Lombardi Satriani1995, 252–3; Castelli Reference Castelli and Cusumano2010, 62–3).

In the Calabrian version reported by Schirripa (Reference Schirripa2000, 256), wild verbena is mentioned by its Calabrian dialect name, bibbia (derived from bibbiana, literally, ‘of the bible’ because, in Roman times, verbena was used by priests, see Castiglioni and Mariotti Reference Castiglioni and Mariotti1980, 1569). However, in Schirripa (Reference Schirripa2000, 256), a footnote defines bibbia as ‘wild plant’ – without including the name of the plant. This suggests that neither the informant nor the collector of the charm were able to identify the plant in question. None of my Calabrian informants were able to identify this plant either.

This lack of familiarity with particular wild plants reflected in verbal folklore is taken to further extremes in a contemporary Sicilian version of the charms in question, reported by Macrina Maffei (Reference Maffei2021, 242). In this Sicilian version, both wild verbena and wild fennel, which was also mentioned in the older versions of the charms, are replaced by pampini i petrusinu (‘leaves of parsley’). Moreover, these are used neither to make eye compresses nor decoctions, as suggested in older versions (e.g. Castelli Reference Castelli and Cusumano2010, 62–3), but used strictly in a symbolic way. Thus, in 2013, one of my younger informants in the Sicilian province of Messina – who was familiar with this particular charm passed down by her grandmother – described this modified version as a ‘superstition’ she did not practise.

All this is indicative of the following: 1) that folklore is a key source of historical knowledge; 2) that what are perceived as ‘superstitions’ today may be decayed folkloric texts – modified from more practical texts – relating to objects or phenomena which are no longer familiar. Consequently, ‘superstitions’ can be taken as a starting point in the search for folkloric texts which carry key, practical information in connection with the real world (medicine, health, the use of specific plants and their parts, etc.). In this context, folklore has become an important source of information concerning wild species which have both medicinal and culinary uses with reference to nutrition, ethnobotany, ethnomedicine, and food sciences (Pieroni et al. Reference Pieroni, Nebel, Santoro and Heinrich2005; Tagarelli, Tagarelli and Piro Reference Tagarelli, Tagarelli and Piro2010; Krippner et al. Reference Krippner, Budden, Gallante and Bova2011; Guarrera and Savo Reference Guarrera and Savo2016). A key aspect to preserving this folklore is rigorous recording with a focus on precisely identifying important elements that are vulnerable to loss and the introduction of references to fixed standards such as botanical names.

In the search for key verbal folklore, however, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms of change. As the preceding examples show, broad socioeconomic changes, such as the move from subsistence farming to cash crops and monoculture, have not only contributed to the change in landscape, but also to an increased unfamiliarity with particular wild plants. Such changes are consequently reflected in the evolution of verbal folklore, where what is useful is retained while the redundant and obsolete are discarded. However, during this process, we can also observe a trade-off between specific knowledge with more immediate benefits and older knowledge which, although relevant to the individual, may have a less immediate benefit or may cost more to maintain and propagate. Understanding these processes can be used to identify surviving environmental and cultural settings where key folklore can be found. This practice could, in turn, expose information relevant to the programme of regional development suggested by Piero Bevilacqua (Reference Bevilacqua1998, 42–3); focusing on piatti tipici (‘traditional dishes’) and plants which were once common in Calabria forming the basis for various folkloric traditions also relating to nutrition, health, and diet (for example the tradition of le tredici cose di Natale, ‘the thirteen things of Christmas’).Footnote 3

Conclusion

This article has demonstrated how modifications to verbal folklore in contemporary Italy reflect and are driven by changes in the people's living environment, thus allowing a deeper understanding of socio-cultural and environmental shifts. In the last 30 years, the verbal folklore that can be transmitted online (such as humorous or moral folkloric texts) has been rendered more generic in order to fit with a wider variety of cultural perspectives. This cultural dilution is not necessarily limited to mass communication, but can also occur in local settings as exemplified by the story of the flageolets.

Within the southern Italian context, changing living conditions have led to changes in verbal folklore which reflect a growing distance between people and the natural world, particularly the land. Some important traditions carried by verbal folklore have lost relevance, not because they lacked viability or because they are not applicable in the modern context, but because of material changes in the people's living environment, such as changes in landscape resulting not only from natural causes, but also from a loss of poly-culture, depopulation of inland rural areas, urbanisation of coastal rural areas, and change in land use which, in turn, are also reflected in verbal folklore. Such changes also drive modifications to folkloric texts reflecting a shift of focus from ends (food, water, etc.) to means (money, mobile phones, etc.) and thus denoting an increased commercial dependence. This shift of focus is also driven by changes in the people's living environment (e.g. technology) which, ultimately, lead to a loss of useful knowledge in folkloric texts relating to the natural environment.

The loss of knowledge in such folkloric texts occurs because those texts depend heavily on points of reference in the real world. When access to those points of reference (e.g. access to wild verbena and other non-cultivated plants) is lost, the dependent practical knowledge deteriorates and, subsequently, is lost or forgotten due to an absence of sensorial experience revolving around those points of reference. Without sensorial experience the knowledge carried by the verbal folklore in question is neither visceral nor emotionally impacting because life and the experience we gain from living is driven by the connection between what we perceive and what we feel. Consequently, the focus of the folkloric text which carried that knowledge shifts to alternative topics of perceived relevance (e.g. from wild pears to peaches or from a concrete to a symbolic level).

Understanding these processes is fundamental in the search for key community knowledge carried by verbal folklore because it orients us in how changes in the cultural landscape reflect changes in the social and environmental landscapes. Consequently, folklore can become one of the tools we use in the recovery of important knowledge applicable in the contemporary context. It can help us understand how a sense of regional identity can be maintained and how historical communal knowledge – in danger of being lost due to changes in living conditions – might be redeployed in the present.

Acknowledgements

This article would not have been possible without the significant folkloric texts including invaluable information provided by each of my informants, and without the excellent suggestions, advice, and editing by Dr Francesco Ricatti, Dr Beatrice Trefalt, and Timothy Casey. My most grateful thanks also go to Modern Italy's reviewers for their constructive comments, helpful suggestions, and key observations that guided me in the process of improving the present article.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Notes on contributor

Liberata Luciani has taught Italian Studies for more than 15 years at Monash University (Melbourne, Australia) where she is currently engaged in a part-time PhD by publication in Italian Studies/Cultural Anthropology with an emphasis on southern Italian folklore, history and society. Her publications relating to this research include: ‘In Memory of Overcoming the Enemy: The Southern Italian Folk Tradition of the “One Hundred Crosses”’. Folklore 128 (June 2017): 133–56; ‘Remembering the Practicalities of Meeting Human Needs: A Southern Italian Folk Tradition with Roots in Ancient “Magic” Practices’, in Ancient Cultures at Monash University, edited by J. Cox, C. Hamilton, K. McLardy, A. Pettman and D. Stewart, 3–10. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2015; and ‘Borrowed, Not Fabricated: The Valley of “Gesufà” in the Sicilian Prayer “U Vebbu”’. Folklore 124 (December 2013): 270–88.