Introduction

Over the past few decades, the study of clientelism has been one of the fastest-growing areas of research in comparative politics (Kitschelt and Wilkinson, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Hicken, Reference Hicken2011; Hicken and Nathan, Reference Hicken and Nathan2020). Using a newly collected, cross-national, party-level data set, we revisit the issue of classifying clientelism. This classification is an important step before exploring the causes and consequences of clientelistic practices across states. Although the micro perspective of clientelism (using experiments and surveys) is highly useful in illuminating the relationship between brokers and voters (Gans-Morse et al., Reference Gans-Morse, Mazzuca and Nichter2014; Nichter, Reference Nichter2008; Stokes, Reference Stokes2005; Stokes et al., Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013), data limitations may prevent scholars from measuring and comparing patron–client relationships across multiple political parties globally over a long-time span. In contrast, the macro perspective that takes the country as the unit of analysis has primarily used country-level data (Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Lo Bue and Sen2022; Lundstedt and Edgell, Reference Lundstedt and Edgell2022; Van Ham and Lindberg, 2015). Despite the benefits of cross-national studies, the analytical scope does not allow us to explore the specific features of clientelistic practices across political parties in each country. This paper bridges these two perspectives by classifying clientelism at the party-level using a global, time-series, cross-sectional, data set.

Recent studies of patron–client relationships have begun to explore how different types of clientelism operate, pointing to dissimilar patterns of clientelistic linkages between politicians and voters (Nichter, Reference Nichter2018; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020; Hicken and Nathan, Reference Hicken and Nathan2020). With these issues in mind, we explore the Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-Party) data set (Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasoglu, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken, Laebens, Medzihorsky, Neundorf, Reuter, Lovell, Weghorst, Wiesehomeier, Wright, Alizada, Bederke, Gastaldi, Grahn, Hindle, Ilchenko, Römer, Wilson, Pemstein and Seim2022), a comprehensive party-level database that records parties’ mobilizational and organizational practices, to map patterns of clientelism.

Specifically, our principal component analysis confirms that clientelism can be classified into (1) a long-term, iterative relationship between parties, brokers, and voters based primarily on strong, organizational networks and state resources and (2) short-term, one-shot interactions between those actors relying primarily on non-state resources and weak organizational ties. The identified patterns of clientelism concur with a recent development of clientelism conceptualization, namely, ‘relational clientelism’ and ‘single-shot (electoral) clientelism’(Nichter, Reference Nichter2018; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020).Footnote 1 Yıldırım and Kitschelt (Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020) used a cross-sectional data set (2008/2009) of clientelism with a smaller number of countries (66 states) from the Democratic Accountability and Linkages Project (DALP). Our analysis includes a much larger number of states (165 countries) over a longer period of time (1970–2019) to find a clearer presence of these two types of clientelism.

To demonstrate the theoretical and empirical validity of our clientelism measures, we apply the composite indices of these two variants of clientelism to analyze the causes of clientelism. We suggest that setting the unit of analysis at the party-level is crucial to understand the rise and decline of distinct patterns of clientelism, because different parties are characterized by dissimilar mobilization strategies within each country. Our application is two-fold.

First, we analyze the effects of economic development on clientelism – one of the traditional topics in research on the macro-level causes of clientelism (Keefer, Reference Keefer2007; Kitschelt and Kselman, Reference Kitschelt and Kselman2013; Stokes et al., Reference Stokes, Dunning, Nazareno and Brusco2013; Van Ham and Lindberg, Reference Van Ham and Lindberg2015; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020). Our analysis reveals that the effects of economic development on clientelism differ depending on the type of clientelism. Relational clientelism, which evolves with strong organizations, tends to persist even in developed economies. In contrast, single-shot clientelism, which prospers with inter-party competition with dispersed, loosely organized networks, has a curvilinear relationship with economic development.

Second, to show the utility of party-level measures of clientelism, we also examine empirically how clientelistic practices change depending on the incumbency status, the tenure lengths of incumbents, and the degree of political centralization. Specifically, our findings indicate that the incumbency advantages tend to be salient in relational clientelism, and the gap between incumbent and opposition parties shrinks when governing parties stay in power for a shorter time and countries are politically decentralized.

This paper contributes to the literature on clientelism. First, we identify empirically the two types of clientelism that scholars have pointed to by using comprehensive panel data on both incumbent and opposition parties. Second, using this comprehensive data set, this study models the inverted U-shaped relationship between economic development and clientelism, which has long been regarded as one of the most important issues in clientelistic exchange. The U-shaped hypothesis has been suggested in the literature, but few scholars have directly modeled and empirically examined this relationship (Kitschelt and Kselman, Reference Kitschelt and Kselman2013). This study fills this gap by drawing a more nuanced picture of the relationship between the two. Third, we tested when the incumbency status is correlated with a specific type of clientelistic exchanges. In so doing, we suggest that ruling and opposition parties develop different forms of clientelism under dissimilar conditions.

Varieties of clientelism

The past decades have seen a preponderance of pertinent studies on clientelism (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2000; Stokes, Reference Stokes2005; Kitschelt and Wilkinson, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007). According to Hicken (Reference Hicken2011), clientelism is defined as the relationship in which an actor in a superior political, economic, and/or social position (the patron) grants various favors to another actor in a subordinate position (the client) in exchange for the client’s political support (i.e., vote).

Recent research suggests that clientelist practices can be classified into several patterns: Depending on the nature of the relationships between votes and favors, clientelism defined above may work differently (Kramon, Reference Kramon2016; Mares and Young, Reference Mares and Young2019; Hicken and Nathan, Reference Hicken and Nathan2020). Specifically, we focus on a pertinent element of clientelistic exchanges – the nature of iterations – to identify varieties of clientelism.Footnote 2 Clientelism may differ also in the capability of patrons to monitor their clients. Scholars have highlighted the role of monitoring and enforcement in clientelistic exchanges (Stokes, Reference Stokes2005; Nichter, Reference Nichter2008). Indeed, monitoring mechanisms are observed in some cases where secret voting does not either exist (Mares, Reference Mares2015; Kuo and Teorell, Reference Kuo and Teorell2017), is compromised (Rueda, Reference Rueda2017), or violated (Corstange, Reference Corstange2016; Frye et al., Reference Frye, John Reuter and Szakonyi2019). Nevertheless, it recently became clear that, in most cases, the mechanisms are generally much weaker than previously believed (Hicken and Nathan, Reference Hicken and Nathan2020).

It is thus crucial to explore if both patrons and clients can expect their relationships to be iterative. In the face of electoral competition, if political parties succeed in dominating the state apparatus and resources, they can also incorporate existing social groups and thus develop extensive organizational infrastructures (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022). Using these assets, public benefits are effectively distributed (Higashijima, Reference Higashijima2022). By controlling state resources, political parties can claim their credit and nurture mutual expectations about their long-term exchanges (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022).

We can locate clientelistic linkages across a wide spectrum. At one extreme, we find clientelistic relationships in which interactions between patrons and clients are expected to continue over the long run; at the other extreme, we find a type of clientelism in which iterations between the two are much weaker. The former type of clientelism is often based on long-term relationships, which are generated through dense party organizations, centralized government institutions, the presence of rich state resources, and/or employment and job security in the public sector and large private companies. Scholars conceptualize this type of clientelism as ‘relational clientelism’ (Nichter, Reference Nichter2018), which involves repeated exchanges through sustained networks that involve (mainly) exchanges of state resources (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022; Berenschot and Aspinall, Reference Berenschot and Aspinall2020; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020).

In relational clientelism, political parties consolidate electoral support by incorporating voters and brokers (e.g., bureaucrats, full-time party staff, managers or employers of state-run or private companies, and key actors of social and informal organizations) into long-term relationships of benefit-vote exchanges. The benefits are primarily drawn from public resources and range from daily necessities and constituency services to small projects, employment in the public and private sectors, various welfare program benefits, and preferential treatment in licensing and public procurement. To create and sustain long-term iterative relationships, parties need to establish a firm grip on the state apparatus and public resources and control the flow of material benefits, so that voters come to believe that voting for (or failing to vote for) a party is likely to be rewarded (punished) (Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020).

In relational clientelism, brokers mediate between parties and voters. Brokers, who are often drawn from existing social organizations, are organized into a hierarchy of party organizations. Their daily contact with clients through well-coordinated, hierarchical networks enables parties to claim credit for the benefits of repeated transactions without relying on monitoring mechanisms (Hicken and Nathan, Reference Hicken and Nathan2020).

This type of clientelism has been widely observed in the former Communist Bloc countries of Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia (Mares and Young, Reference Mares and Young2019; Reuter, Reference Reuter2017; Higashijima, Reference Higashijima2022) as well as in dominant party states that have appeared in Latin America, Asia, and Africa (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2006; Washida, Reference Washida2019; Weiss, Reference Weiss2020a). For instance, public employees, such as bureaucrats, teachers, and doctors in the post-Soviet states, are strongly captured by the practices of relational clientelism, which is orchestrated by dominant parties, such as United Russia and Kazakhstan’s Nur-Otan. Under iterative relationships between politicians and these citizens employed in public sectors, the citizens were forced to vote for ruling parties despite their middle-income status in exchange of various tangible benefits, including long-term job security and multiple announcements of salary increases and bonuses (Rosenfeld, Reference Rosenfeld2020; Higashijima, Reference Higashijima2022).

As a recent comparative study of Southeast Asian countries (Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia) by Aspinall et al. (Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022) shows, whether parties succeed in establishing a firm grip on public resources and state apparatus during the regime-building period is the key to the successful development of distributive machinery for iterative relationships with brokers and voters. The long-term dominance creates virtuous cycles of advantages and allows incumbent parties to establish credible clientelistic exchanges without relying on monitoring and enforcement mechanisms at the individual level. For example, without intensive monitoring and hijacking welfare programs for partisan benefits, incumbent parties can systematically exclude opposition parties from public resources particularly in unitary systems or highly centralized federations, such as Malaysia (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022; Washida, Reference Washida2019), although elected regional governments help opposition parties to gradually erode incumbent dominance (e.g., Weiss, Reference Weiss2020b).

In contrast, the latter type of clientelism can be conceptualized as ‘single-shot clientelism’ or ‘electoral clientelism,’ wherein organizational ties linking patrons, brokers, and clients are weak and the access to public resources is often limited and intermittent. Consequently, the time horizon for the relationship between them tends to be short (Novaes, Reference Novaes2017; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020; Hicken et al., Reference Hicken, Aspinall, Weiss Meredith and Burhanuddin2022). This type of clientelism involves only one-off, pre-electoral exchanges mainly through money and consumer goods with weak organizations, ad hoc personal networks, and non-state, often individual resources.

In single-shot clientelism or electoral clientelism, loosely connected brokers (e.g., family members and relatives, business associates, paid community residents, and criminal groups) are mobilized in an ad hoc manner only during election campaigns (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022; Berenschot and Aspinall, Reference Berenschot and Aspinall2020; Hicken et al., Reference Hicken, Aspinall, Weiss Meredith and Burhanuddin2022; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020). Brokers are not necessarily embedded in hierarchical organizations in the same manner as well-institutionalized parties. Thus, they are mobilized mainly during election campaigns carried out by individual candidates. Candidates raise their campaign funds by themselves and distribute cash, food, consumer goods, and other relatively small-scale benefits to voters during electoral campaigning. Therefore, single-shot clientelism cannot adequately ensure credible exchange between votes and benefits (Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020).

These seemingly ineffective mobilization strategies may persist because voters expect politicians to distribute money for voters’ benefits and candidates feel obliged to deliver benefits to compete with other rival candidates who may also deliver benefits to garner votes (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022). Comparativists point to possible mechanisms, such as the roles of goods provisions by candidates as costly signals of their credibility and competence as viable legislators (Muñoz, Reference Muñoz2018; Kramon, Reference Kramon2016). Because of the absence of organized parties and brokers and the lack of information about parties and candidates, unwarranted distribution of cash, food, and consumer goods becomes an appealing strategy (Muñoz, Reference Muñoz2018).

Consistent with this observation, single-shot (electoral) clientelism has been widely observed in various cases in Southeast Asia, including in the Philippines, in post-Suharto Indonesia, and in democratic spells in Thailand. It has been observed also in Latin America, such as in Peru, Guatemala, and Colombia; and in sub-Saharan Africa, such as Benin, Ghana, and Kenya (Aspinall and Berenschot, Reference Aspinall and Berenschot.2019; Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022; Hicken et al., Reference Hicken, Aspinall, Weiss Meredith and Burhanuddin2022; Muñoz, Reference Muñoz2018; Kramon, Reference Kramon2016).

For instance, because parties in Indonesia (except Golkar) could not get access to state resources during the Suharto regime, parties in the post-democratization era cannot help relying on individual candidates’ informal campaign teams and their private resources to distribute goods. Without stable access to state resources, parties fail to incorporate existing social organizations and therefore cannot develop long-term relationships with brokers and voters. Although capturing local governments and their public resources by local political dynasties enables some parties to build relatively iterative relationships at local levels in decentralized systems (as the case of the Philippines), such practices tend to remain at specific localities (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022).

Classifying clientelism

Building on the above-mentioned conceptualizations of relational and single-shot clientelism (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022; Berenschot and Aspinall, Reference Berenschot and Aspinall2020; Hicken and Nathan, Reference Hicken and Nathan2020; Hicken et al., Reference Hicken, Aspinall, Weiss Meredith and Burhanuddin2022; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020; Nichter, Reference Nichter2018), we identify and operationalize these two types of clientelism by employing party-level panel data. We then compare our estimation results with existing indices (from V-Dem and DALP) (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton, Pemstein, Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Tzelgov, Uberti, Ting Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2022; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2013). We suggest that the V-Dem data do not allow us to capture the two types of clientelism, whereas the DALP data, which focus more on types of goods provisions, is cross-sectional with limited country coverage.

A principal component analysis of clientelism

To empirically identify relational and single-shot clientelism, we conducted a principal component analysis of the V-Party data. Given that parties often become a center of relationships between patrons, brokers, and clients, it is useful to set political parties as the unit of analysis.Footnote 3 Understanding the differences within each country helps us to explore how the inter-party differences emerge and decline and how national variables, including economic development, condition the differences of clientelist mobilization (Kitschelt and Wilkinson, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Kitschelt and Kselman, Reference Kitschelt and Kselman2013; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020). To the best of our knowledge, the V-Party data set is the most extensive party-level panel data that comprehensively measures the organizations, identities, election campaigning methods, and policy platforms of 1,955 political parties in 169 countries from 1970 to 2019. Specifically, we use the following six items from the V-Party data set (Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasoglu, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken, Laebens, Medzihorsky, Neundorf, Reuter, Lovell, Weghorst, Wiesehomeier, Wright, Alizada, Bederke, Gastaldi, Grahn, Hindle, Ilchenko, Römer, Wilson, Pemstein and Seim2022).

The first two items capture to what extent a political party relies on clientelist strategies to gather political support in the first place. Specifically, the V-Party measures a party’s identity in respective issues based on ‘the positions that a party expressed before the election through official communication, e.g., election manifesto, press releases, official speeches and media interviews’ (Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasoglu, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken, Laebens, Medzihorsky, Neundorf, Reuter, Lovell, Weghorst, Wiesehomeier, Wright, Alizada, Bederke, Gastaldi, Grahn, Hindle, Ilchenko, Römer, Wilson, Pemstein and Seim2022, p.26). Drawing from the identity variables, the first item measures to what extent a political party depends on clientelistic exchange when mobilizing supporters (v2paclient).Footnote 4 Because the first item measures only the party position in clientelist interactions, we also include the second item, which evaluates the salience of clientelist mobilization. It measures how outstanding clientelistic exchange is as a tool in mobilizing supporters for a political party (v2pasalie_11).Footnote 5

Although these two items are useful in capturing how important clientelistic practices are for political parties, they do not necessarily differentiate (1) what channels and networks they employ (i.e., organizational strengths) and (2) what sources they primarily use for clientelistic exchanges (i.e., sources of funding). To consider the first dimension, two items relate to the effectiveness of party machines that form iterative relationships.

As discussed above, relational clientelism relies on coordinated party machinery for structuring the flow of resources and organizing distributive networks. Single-shot (electoral) clientelism lacks a comparable organizational foundation and resorts to informal, ad hoc individual networks. To measure the strength of mass party organizations, we include items that evaluate whether parties have permanent party offices (v2palocoff) and staff in local communities (v2paactcom).Footnote 6 In relational clientelism, party offices and staff serve as coordinated brokers who constantly mediate the iterative exchanges between parties and voters by connecting with existing, prominent, social organizations. Well-developed party organizations financed by public resources also provide the infrastructure for iterative interaction. In contrast, parties without such organizational infrastructures rely on individual candidates’ personal, ad hoc networks to cultivate votes. Therefore, they fail to sustain constant exchanges.

Sources of funding are the second dimension that influences the nature of iterations. Therefore, two other items represent the funding sources of election campaigning. Again, the relational type of clientelism enables patrons to enjoy access to state resources, whereas the single-shot type usually lacks such state resources and relies more on individual candidates to raise campaign funds by themselves (Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020; Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022). We thus employed two variables on the sources of campaign funds: the informal use of state resources as an incumbent partyFootnote 7 and the funds of individual candidates (v2pafunds_5 and v2pafunds_7).Footnote 8 It is worth noting that state resources here are not necessarily limited to those of the central government. The data imply that opposition parties often receive state resources, for example, by controlling governorships in state governments (Lucardi, Reference Lucardi2016; Weiss, Reference Weiss2020b).Footnote 9 , Footnote 10

Using these variables, we conducted an unrotated principal component analysis.

The results are presented in Table 1, and the factor loading plot appears in Figure 1.Footnote 11 The analysis identifies two major components, which we can interpret as relational and single-shot types of clientelism. The substantive image implied by the results fits well with the conceptualizations presented above. The factor loading in the first component is all positive and sufficiently high except for the sixth item (fundraising by individual candidates). In contrast, parties ranked higher in the second component tended to lack robust party machinery (e.g., local offices and party staff and activists) and therefore relied heavily on individual candidates’ efforts to raise funds rather than to depend on state expenditures.

Table 1 Results of principal component analysis

N = 6228. Bold numbers > |0.4|.

Figure 1. Factor loading plot.

The first axis explains 38.7% of the variance, and the second axis explains 27.9% of the variance. This means that more than two-thirds of the total variance is explained by these two components, and both appear nearly equally important in explaining variation. We decided on the number of dimensions by referring to both eigenvalues (shown in Table 1) and a scree plot (online Appendix B.1). Based on the estimation results, we created predicted values of relational and single-shot clientelism by computing principal component scores. The indicators are re-scaled so that the minimum and the maximum are set to zero and one, respectively.

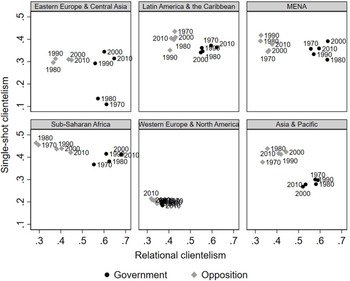

Both dimensions are extracted as independent indicators (given the nature of principal component analysis) and each party has varying values of the two types of clientelism. To draw a substantive picture of these indicators, Figure 2 illustrates the means (weighted by seat shares) of the two clientelism indicators, differentiated by government status (leading government parties or opposition parties), regions (V-Demś e_regionpol_6C), and time periods (each decade).

Figure 2. Factor loading plots.

As expected, developed countries in Western Europe and North America have lower values of the two clientelism indicators. In the Asia-Pacific region, government parties rely more on relational clientelism, whereas opposition parties depend more on single-shot clientelism. In Latin American, MENA, and Sub-Saharan African countries, government parties tend to have features of both relational and single-shot clientelism, whereas opposition parties more clearly develop only single-shot clientelism. Figure 2 also illustrates time trends. For example, in Sub-Saharan Africa, opposition parties gradually nurtured relational clientelism, and government parties expanded the use of single-shot clientelism over time.

Appendices C.1 and C.2 (online) list 50 parties with high principal component scores of relational and single-shot clientelism, respectively. Although we include all the parties in the principal component analysis, the lists restrict the sample to parties that experienced more than three elections to ensure the results fit well with our intuition. Interestingly, parties that ranked higher in the lists generally resonate with prominent cases referred to in the existing studies of clientelism. For example, online Appendix C.1 (relational clientelism) includes typical cases taken up by the studies of authoritarian dominant parties and relational clientelism (e.g., Higashijima, Reference Higashijima2022; Magaloni, Reference Magaloni2006; Reuter, Reference Reuter2017; Washida, Reference Washida2019), such as PDGE (Equatorial Guinea), PRI (Mexico), Colorado Party (Paraguay), PJ (Argentina), ZANU-PF (Zimbabwe), RPP/UMP (Djibouti), CCM (Tanzania/Zanzibar), KMT (Taiwan), UMNO (Malaysia), Golkar (Indonesia particularly under Suharto), Nur-Otan (Kazakhstan), UR (Russia), and the Communist Party (Soviet Union).Footnote 12

Similarly, typical cases discussed in research on single-shot clientelism appear in online Appendix C.2. They include parties in Thailand (NDP, PKS, PCT, NAP, PP, TCP), the Philippines (PNP, LDP, KMB, Lakas-CMD, PLP), East Malaysia (PBS), Guatemala (PID, UNE, PR, PAN, FRG, UCN, MLN), Brazil (minor parties, such as PPB and PTB), and Benin (UDNS, MADEP, PSD, RB).Footnote 13 In stark contrast to relational clientelism (online Appendix C.1), multiple parties are listed from the same countries in the case of single-shot clientelism (online Appendix C.2). The number of cases winning or retaining office within the total number of contested elections is much lower than those of higher-ranked countries in relational clientelism (online Appendix C.1). This implies that single-shot clientelism may be more easily formed. Cementing electoral support via single-shot clientelism may also be more difficult than through relational clientelism. Our analysis of classification and data explorations enable us to draw a comprehensive, accurate map of varieties of clientelism by delving into variation in the two types of clientelism across political parties on the globe. One important question then is: Do the results of our classification differ from those of other existing data sets? The next subsection addresses this question.

Comparisons with existing indicators of clientelism

Here we compare our measurement strategy with two prominent country- and party-level indices proposed by previous research, namely the Varieties of Democracy project (V-Dem, Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton, Pemstein, Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Tzelgov, Uberti, Ting Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2022) and the DALP (Kitschelt and Kselman, Reference Kitschelt and Kselman2013; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020). Through a comparison with these indicators, we highlighted the differences and strengths of our approach. Table 2 summarizes the main features of each project, such as country and temporal coverage, types of clientelism, and levels of aggregation.

Table 2 Main features of the three projects on clientelism measurement

V-Dem data set

A stream of empirical studies has analyzed cross-national variance in the prominence of clientelistic mobilization (Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Lo Bue and Sen2022; Lundstedt and Edgell, Reference Lundstedt and Edgell2022; Van Ham and Lindberg, Reference Van Ham and Lindberg2015). In particular, a series of indicators developed by the V-Dem project has contributed to renewed interest in clientelism.Footnote 14 The V-Dem provides four indicators related to clientelism: (1) the degree of vote buying (v2elvotbuy)Footnote 15 , (2) the extent to which excludable goods (private and club goods) and public goods make up a share of the budget (v2dlencmps),Footnote 16 (3) an assessment of whether the linkage strategies of major parties are clientelistic or policy/programmatic (v2psprlnks),Footnote 17 and (4) a composite index of these three items created using a Bayesian factor analysis model (v2xnp_client).Footnote 18

An advantage of using the V-Dem data is its extensive coverage of not only the number of countries (175) but also of time (from 1789 to 2021). However, the V-Dem indices suffer several drawbacks. First, although these indicators are based upon a broad definition of clientelism (e.g., Hicken, Reference Hicken2011), they do not necessarily correspond to the classifications elaborated by the recent studies (i.e., relational and single-shot types of clientelism). As individual indicators on clientelism in the V-Dem data set are drawn from different theoretical perspectives, it is unclear to what extent they overlap or capture mutually distinct aspects of different types of clientelism.

Moreover, macro-level indices, such as the V-Dem data, do not allow us to compare political parties. In the V-Dem expert survey, experts are asked to evaluate national-level averages of clientelistic practices. In other words, each coder evaluates a specific country-year data point by referring to multiple parties within the country. This aggregation process masks important differences among political parties within countries, even though the V-Dem adjusts inter-coder differences in evaluation criteria and coder reliability. In this regard, a party-level data set, such as the V-Party, helps scholars directly analyze inter-party differences within countries.

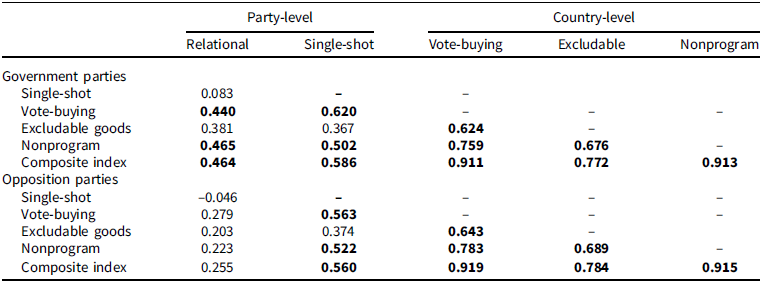

To compare our indicators with the V-Dem indicators, Table 3 presents simple bi-variate correlations between our relational and single-shot indicators and four V-Dem indicators related to clientelism. To simplify our interpretation, three V-Dem indicators were reversed so that higher values represent the relative saliency of respective clientelism measures. We set the unit of analysis as party and then merged the V-Dem indicators with the party-level V-Party data. In calculating the correlations, we broadly divided the sample into government parties (including coalition partners) and opposition parties (including unaffiliated parties).Footnote 19

Table 3 Correlations between V-Party-based indicators and V-Dem indicators

N = 2,699 (government parties), N = 3,278 (opposition parties). Bold numbers > |0.4|.

The table indicates that, although the V-Dem measures of clientelism are associated with both relational and single-shot clientelism, the V-Dem indicators have slightly higher correlations with single-shot clientelism. In addition, these V-Dem indicators are more positively correlated with the two types of clientelism in the sample of government parties than with those of the opposition parties. Because it is inevitable to flatten within-country variation in the aggregating process, we had to keep in mind what may be missed when using these indicators. Moreover, high correlations among the V-Dem individual indicators suggest that they are likely to overlap conceptually and thus they may not be suitable to distinguish between the two dissimilar types of clientelism.Footnote 20

DALP data set

In contrast to the country-level indicators, party-level measurements enable us to conduct fine-grained analyses. By setting the unit of analysis at the party level, we were able to analyze clientelism as a mobilization strategy of parties. The aforementioned DALP database provides an extensive party-level data set, which covers 506 parties from 88 countries in 2008/2009 (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt2013). It primarily features four aspects of information regarding political parties: (a) local and municipal-level party organizations, (b) exchange mechanisms, (c) monitoring and enforcement, and (d) party policy positions.

To explore the types of clientelism, Kitschelt and his colleagues (Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020) conducted a principal component analysis focusing on the types of benefits delivered in clientelistic exchange. Specifically, they used the items of (b1) consumer good provision,Footnote 21 (b2) preferential public benefits,Footnote 22 (b3) employment opportunities,Footnote 23 (b4) government contracts,Footnote 24 and (b5) regulatory proceedings.Footnote 25

Restricting the sample to less developed countries (362 parties in 66 countries), Yıldırım and Kitschelt (Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020) argued that clientelistic exchanges can be classified into relational and single-shot modes. The results of their analyses indicated that electorally and organizationally robust incumbent parties are more likely to develop relational clientelism, whereas organizationally weak opposition parties tend to resort to single-shot clientelism in the developing world.

Their work is an important first step in the study of party-level clientelism. In particular, the DALP data set is the only cross-national, party-level data set that enable us to identify specific types of goods that patrons offer to clients. However, there are still issues to be addressed by further research. In addition to the problem of a limited geographic scope (88 countries),Footnote 26 the first issue is that the time coverage of the DALP data is limited to a single data point (2008 or 2009). In general, analyses of cross-sectional data are likely to encounter omitted variable biases, because it is difficult to control for country- and time-specific confounders. We do not know yet whether their findings apply when we use panel data covering a wide range of countries and time periods.

The second problem is the validity of the two-dimensional conceptualization using DALP. Although their classification based on the type of goods is theoretically reasonable, these five items are, in fact, highly correlated. Therefore, we need to be careful in validating the two-dimensional measurements of clientelism. For example, standard criteria in selecting the number of dimensions of a principal component analysis using the DALP data set, such as eigenvalues or a scree plot, indicate that a single dimension is sufficient to explain the variance (online Appendices B.2 and B.3).

We replicated the principal component analysis (both with and without rotation) using the DALP data set (excluding developed countries, following Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020). We found that the first dimension explains most of the variance (79%), whereas the second dimension explains only a marginal variance (9%). The eigenvalue of the first dimension is 3.93, whereas that of the second dimension is less than 0.5, falling short of the standard cut-point (1.0). The results are similar when we use all 88 countries included in the data (see online Appendices B.2 and B.3). Based on these two dimensions, Yıldırım and Kitschelt (Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020) created indicators of relational clientelism (means of b2, b3, b4, and b5) and single-shot clientelism (b1).Footnote 27 However, the correlation between these two indicators is extremely high (greater than 0.8). Their measure of relational clientelism is highly correlated with our measures of relational and single-shot clientelism, and the same holds for their measure of single-shot clientelism.Footnote 28 This indicates that their measurements do not necessarily capture well the varieties of clientelism.

Our principal component analysis of the V-Party data is highly useful in addressing the issues that DALP encounters. The broad country and time coverage of our data set is useful for scholars, who want to extend the analytical scopes of cross-national party-level research of clientelism while increasing measurement accuracy and employing multi-level, panel data estimators. Our measures of clientelism do not directly capture various practices of goods exchange but well capture the organizational aspects of clientelistic linkages in addition to the presence of clientelistic practices.

Recent research strongly suggests that, not merely focusing on what goods patrons try to distribute, it is also important to look at how these goods are distributed via organizations and types of resources (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022; Berenschot and Aspinall, Reference Berenschot and Aspinall2020; Hicken and Nathan, Reference Hicken and Nathan2020). For example, welfare programs can be implemented as programmatic public goods provision as a contingent reward mediated by a well-organized party machinery (as in Malaysia); they could be also deployed as particularistic private goods ‘morselized’ (or apportioned) by local political families (as in the Philippines) (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022). Given that these insights have not yet been well captured on cross-national data, it would still be a value added to use the V-Party data to define clientelism based on what the recent literature suggests.

We hope our indicators of relational and single-shot clientelism contribute to refining the comparative analysis of clientelism in future research. As a preliminary step to validate our indicators of party-level clientelism, the next section explores determinants of divergent patterns of clientelism by focusing primarily on the differences between governing and opposition parties.

Applications of the new clientelism measures

In this section, we examine economic development – one of the most prominent structural factors that have attracted continuous attention by comparativists, to the development of clientelism. Moreover, because ruling parties are in a better position to exploit state resources, we analyze whether government (opposition) parties are more likely to employ relational (single-shot) clientelism (Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020). The multi-level analysis of the V-Party data provides an unusual opportunity to explore how incumbent/opposition parties adopt divergent strategies of clientelistic mobilization, depending on the different levels of economic development. Note that we examine relevant associations between the key variables, and not causality. Using the most comprehensive party-level data of clientelism, we assess empirically at which levels of economic development and under which conditions strong clientelistic practices may emerge.

Economic prosperity

Conventional wisdom suggests that the relationship between clientelism and economic development is an inverted U-shape due to competing effects (Kitschelt and Kselman, Reference Kitschelt and Kselman2013; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020). At the lowest level of economic development, parties cannot gain access to both public and private resources (Kitschelt and Wilkinson, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007). Therefore, clientelism does not become salient in the least developed countries. As the economy develops, economic resources in society and state expand, providing political parties with rich sources of funding to mobilize electorates. This in turn heightens people’s expectations of the distributive capacities of political parties.

At the same time, economic development also lowers the effectiveness of clientelistic mobilization by increasing the economic autonomy of voters. Voters are less induced by economic incentives when they become more affluent, educated, and urbanized (Kitschelt and Wilkinson, Reference Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Weitz-Shapiro, Reference Weitz-Shapiro2014). Economic development also enables poor voters to escape from the ‘poverty trap’ imposed by ruling parties.

Together, the relationship between economic prosperity and clientelism leads to an inverted U curve: practices of clientelism tend to be less observed in the poorest and richest countries and they become most salient in middle-income countries. Despite limited evidence for this curvilinear relationship (Kitschelt and Kselman, Reference Kitschelt and Kselman2013), it is still uncertain under what conditions economic development promotes what types of clientelism.

We argue that these competing effects of economic development operate differently depending on the type of clientelism. Specifically, the positive effect (i.e., increasing resources for political parties) is expected to be stronger for relational clientelism because parties with institutional infrastructures can effectively translate the increased amount of resources into electoral support while mitigating the negative effect of economic development on the efficiency of clientelism (i.e., decreasing marginal return of electoral support from voters). For example, in relational clientelism, parties can extend the quid pro quo relationship to welfare programs, public and private employment, and other crucial benefits to entrench brokers and voters in iterative relationships (Frye et al., Reference Frye, John Reuter and Szakonyi2019; Mares and Young, Reference Mares and Young2019). In contrast, the negative effect of economic development may be more salient for single-shot clientelism, which lacks the organizational infrastructure to entrench affluent voters.

Hypothesis 1a: The prominence of relational clientelism is positively associated with economic development.

Hypothesis 1b: The prominence of single-shot clientelism is strongest in middle-income countries and becomes weaker in poorer and richer countries (inverse U-shaped relationship).

Conditional incumbency advantages

We also examined whether the prominence of clientelism may change depending on whether parties are in office or in opposition. As reviewed earlier, we can think of mechanisms to sustain iterative exchanges in relational clientelism. Although this type of clientelism is more effective than single-shot clientelism, parties need to develop a well-coordinated party machinery and establish a firm grip on bureaucracy, budgetary resources, and substantial parts of the economy. Given the higher costs of investing in such organizational infrastructures, ruling parties are in a better position to develop relational clientelism than opposition parties, which often lack resources and opportunities (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022; Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020).

In contrast, single-shot (electoral) clientelism relies on loose and ad hoc networks of brokers employed by individual candidates (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022; Hicken et al., Reference Hicken, Aspinall, Weiss Meredith and Burhanuddin2022). Although the major resources employed in this type of clientelism, such as cash handouts and the provision of consumer goods, often lack long-standing interactions, single-shot clientelism does not require parties to invest in developing well-coordinated organizations. Therefore, even opposition parties can enjoy equivalent opportunities for utilizing single-shot clientelism without investing in organizational infrastructure as long as they have access to informal networks or private resources of their own (Yıldırım and Kitschelt, Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020). Government parties without a sufficient capacity to develop effective relational clientelism may also have incentives to use this type of clientelistic mobilization.

Hypothesis 2a: The gap between government and opposition parties is more salient in relational clientelism than in single-shot clientelism.

Moreover, as implied in the previous subsection, the effects of economic development on clientelism may differ not only according to the types of clientelism but also the parties’ incumbency status. For example, although relational clientelism may thrive even at higher levels of economic development, economic development narrows the incumbency advantage by making it difficult to sustain control over the economy and by providing opposition parties with diverse financial sources for clientelistic purposes. It is thus expected that:

Hypothesis 2b: The government-opposition gap in relational clientelism tends to be narrower in developed economies.

Regarding conditional effects on single-shot clientelism, Yıldırım and Kitschelt (Reference Yıldırım and Kitschelt2020) suggest that government parties are better at cultivating relational clientelism, whereas opposition parties are more likely to focus on single-shot clientelism. However, because of relatively low costs in developing single-shot clientelism, government parties may also find it useful to develop single-shot clientelism when necessary. Therefore, we expect no significant gap between government and opposition parties in single-shot clientelism across different levels of economic development.

Furthermore, although government parties enjoy an advantageous position in developing relational clientelism, the incumbency advantage may depend also on the lengths of tenure and the types of clientelism. Newly inaugurated government parties need some electoral terms to establish a firm grip on state apparatus, learn how to direct the flow of state resources, and develop organizational infrastructures (Bolleyer and Ruth, Reference Bolleyer and Ruth2018) and networks of brokers, who share the long-standing expectations about clientelistic exchanges. In contrast, it does not take a long period of time to employ single-shot clientelism, which requires private resources and ad hoc networks. Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2c: How long ruling parties have been in power is positively associated with the strength of relational clientelism but not with the strength of single-shot clientelism.

Various institutional factors are likely to mediate the effect of economic development and incumbency status. Among others, federal structures may condition the development of clientelistic exchanges. The existence of elected, autonomous, regional governments allows various actors to gain access to public resources. This makes it difficult for government parties to establish incumbency advantages in cultivating relational clientelism, while enabling opposition parties to develop relational clientelism by capturing local public resources by winning the governorship of regional governments. Even under the dominance of ruling parties, opposition parties build their own clientelistic networks by employing budgetary resources of sub-national governments, as illustrated by the cases of Mexico and Malaysia (Lucardi, Reference Lucardi2016; Weiss, Reference Weiss2020b). Decentralized political systems further expand the opportunities for (both incumbent and opposition) parties and individual politicians hankering for materialistic benefits to which local governments are entitled, as demonstrated by the Philippines (Aspinall et al., Reference Aspinall, Weiss, Hicken and Hutchcroft2022). These discussions lead to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: The government-opposition gap in relational clientelism tends to be narrower in decentralized political systems.

Variables and estimator

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a multi-level panel data analysis. We used the party-level data merged with a series of country-level variables. The main clientelism variables consisted of 6,186 party-election years of 1,894 parties in 167 countries from 1970 to 2019. The number of observations in the following analysis is slightly smaller due to the limited availability of explanatory variables.Footnote 29 The dependent variables are the re-scaled indicators of relational and single-shot clientelism, drawn from the principal component analysis in the previous section.

To test the effects of economic development on clientelism (H1a and H1b), the main explanatory variables are lagged GDP per capita (e_gdppc times 1000 from V-Dem) in log and its squared term. To assess the relationship between the type of clientelism and the incumbency advantage (H2a and H2b), we included the variable of incumbency status with a three-point scale (2 for the leading government parties, 1 for coalition and affiliated parties, and 0 for opposition parties), based on the government status variable (v2pagovsup) of the V-Party. Moreover, to explore whether the effect of economic development is conditioned by government status (H2b), we added interaction terms between the incumbency-status variable and the economic development variable (including its squared term). When calculating the tenure lengths of incumbent governments (H2c), we calculated the number of consecutive elections, in which parties sustained the leading government status since the first year of the data (1970). Because there is a limited number of parties that survived more than five elections, the values higher than four were coded as five.

To assess H3, we used the dummy variable of decentralized system using the regional government index (v2xel_regelec) of V-Dem, which assesses the existence of elected regional governments and their autonomy.Footnote 30 Because the distribution of this index is polarized into the lower and higher values, we created a dummy variable, which counts one for the highest quarter of the V-Dem data (in preceding years).

In addition to these variables, we included some important control variables that are likely to affect both the degree of clientelism and the explanatory variables, such as lagged economic growth rate (annual growth of e_gdppc from V-Dem) and year- and region-fixed effects. We employed a three-level multilevel estimator (hierarchical linear model) to account for the nested structure of the data, i.e., election years nested in the party and then country levels. The multilevel model of the party-level panel data provides the best opportunity to explore how ruling and opposition parties develop divergent types of clientelistic mobilization depending on the levels of economic development.Footnote 31

Results and Discussion

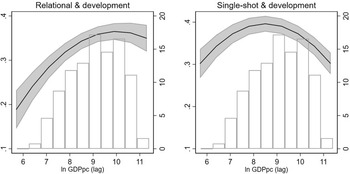

Figure 3 presents the results for relational clientelism and single-shot clientelism. The left panel of the figure shows the results for relational clientelism, and the right panel represents those for single-shot clientelism. The panels show how predicted values of each type of clientelism change depending on levels of economic development (H1a and H1b).

The left panel shows a positive association between relational clientelism and economic development (as expected in H1a). The prominence of relational clientelism reaches its peak when GDP per capita is approximately 30,000 USD and starts diminishing thereafter. In contrast, the right panel indicates that the relationship between single-shot clientelism and economic development follows a clear inverse U-shaped form (as expected in H1b).Footnote 32 Its peak comes much earlier (approximately 5,000 USD) and quickly diminishes thereafter. These contrasting findings may suggest a way to interpret the mixed results of previous studies on why economic development suppresses clientelism in some countries but not in others. As discussed earlier, relational clientelism can thrive even in developed economies by entrenching bureaucrats, brokers, employers of public sectors, and the middle-class voters who depend on the government distribution. In contrast, single-shot clientelism lacks such institutional infrastructures and thus fails to control loosely connected brokers and increasingly affluent voters.

We also suggested that the relationships between clientelism and economic development may differ according to whether parties are incumbent (H2a and H2b). Figure 4 shows how the curvilinear relationships change depending on incumbency status (the straight line represents the incumbent and the dashed line the opposition, respectively).

In line with H2a, the gap between government and opposition parties is larger in relational clientelism than in single-shot clientelism: in the case of single-shot clientelism, the confidence intervals are overlapped (right panel), whereas they rarely overlap in the case of relational clientelism (left panel). Ruling parties enjoy a more advantageous position in establishing relational clientelism. However, the gap in relational clientelism between governing and opposition parties becomes narrower as economic developments advance by constraining incumbency advantages and empowering opposition parties.

Figure 5 shows how the strengths of clientelism change according to the tenure lengths of incumbents (H2c). As expected, incumbents who stay in power longer tend to have higher levels of relational clientelism (left panel). In contrast, how long incumbents stay in office is not positively associated with the development of single-shot clientelism. Rather, the correlation is slightly negative although the change seems not to be statistically significant. The overall results offer strong evidence supporting Hypothesis 2c.

Lastly, Figure 6 investigates how the relationship between economic development and clientelism may change according to political (de)centralization. For relational clientelism, incumbents tend to have clear advantages across a wide range of economic development levels under centralized political systems (upper left panel). Ruling parties have larger scores of relational clientelism than opposition parties in low- and middle-income countries. The difference becomes statistically indistinguishable from zero only in very rich countries. If a country is politically decentralized, the difference between ruling and opposition parties becomes statistically insignificant except for middle-income countries (upper right panel). These results are in line with Hypothesis 3: ruling parties have stronger advantages in cultivating relational clientelism vis-a-vis opposition parties under centralized political systems; opposition parties can engage in relational clientelism if countries adopt decentralized political systems. In contrast, political (de)centralization does not make a significant difference in the degree of single-shot clientelism between governing and opposition parties. Given that single-shot clientelism is orthogonal to the allocation of state resources, the results are consistent with our theoretical expectations.

Conclusion

This paper elucidated factors behind clientelism from a party-level perspective. We used newly collected party-level data (V-Party) and conducted a principal component analysis to capture two types of clientelism – relational and single-shot (electoral) types of clientelism.

We then conducted a preliminary analysis of the causes of clientelism. Our analysis found that the conventional wisdom of the curvilinear relationship between clientelism and economic development can be applied only to single-shot clientelism. Our findings contribute to the reconciliation of the mixed results of the effect of economic development on clientelism and answer why clientelism remains intact in some developed countries.

Our analysis also demonstrated that we may need to differentiate political parties according to their incumbency status. The new measures of clientelism are highly useful for this purpose. Our results showed that ruling parties have greater advantages in cultivating relational clientelism and such incumbency advantages tend to be strengthened as they stay in power longer. We also showed that such incumbency advantages may also be curtailed if political systems are highly decentralized.

This paper is an important first step in improving the measurement of clientelism and understanding the correlates of clientelism according to multi-level, cross-sectional, time-series perspectives. However, there are likely other relevant factors that nurture these types of clientelism, such as electoral systems, state capacity, and the amount and type of financial resources of political parties. Furthermore, additional cross-national analysis may be needed to illuminate the mechanisms operating behind the correlations identified in this study. Incorporating the types of goods in our measurements will help better understand the causes and consequences of clientelism.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000309

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by JSPS grants-in-aid (Grant Numbers 19KK0337 and 21H00678). We deeply appreciate Allen Hicken, Matthew Charles Wilson, and the three anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments and feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.