Introduction

It is widely alleged by practitioners (e.g., Gleeson, Reference Gleeson2017; Maurer, Reference Maurer2010) and academics (e.g., Beer & Nohria, Reference Beer and Nohria2000; De Keyser, Guiette, & Vandenbemp, Reference De Keyser, Guiette and Vandenbemp2019; Gilley, Dixon, & Gilley, Reference Gilley, Dixon and Gilley2008) that most organizational changes fail, with figures of 60–90% often cited. However, the ‘evidence’ for such claims is often either negligible (e.g., citing other authors who make the assertion) or not provided. Similarly, the failure rate of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) is claimed to be somewhere between 50 and 90% and here again there is little documentation for such numbers (e.g., Christiansen, Alton, Rising, & Waldeck, Reference Christiansen, Alton, Rising and Waldeck2011; Dauber, Reference Dauber2012; Dorling, Reference Dorling2017; Jacobs, van Witteloostuijn, & Christe-Zeyse, Reference Jacobs, van Witteloostuijn and Christe-Zeyse2013; Spoor & Chu, Reference Spoor and Chu2018). To be fair, the claims are usually made in the introduction to academic articles whose contents focus on discrete factors that are antecedents of success or failure in M&A, such as integration processes (Christiansen et al., Reference Christiansen, Alton, Rising and Waldeck2011), identity (Jacobs, van Witteloostuijn, & Christe-Zeyse, Reference Jacobs, van Witteloostuijn and Christe-Zeyse2013; Spoor & Chu, Reference Spoor and Chu2018), organizational culture (Dauber, Reference Dauber2012) and psychological capital (Dorling, Reference Dorling2017).

Definitions of failure, in and of organizations, vary significantly across authors and disciplines, such as strategy (Muehlfeld, Sahib, & van Witteloostuijn, Reference Muehlfeld, Sahib and van Witteloostuijn2012), entrepreneurship (Singh, Corner, & Pavlovich, Reference Singh, Corner and Pavlovich2007), management and organizational behaviour (De Keyser, Guiette, & Vandenbemp, Reference De Keyser, Guiette and Vandenbemp2019; Walsh, Pazzaglia, & Ergene, Reference Walsh, Pazzaglia and Ergene2019). This also penetrates the debate on what constitutes success/failure in M&A, and how it is evaluated and measured. Does one judge the outcomes of M&A in objective terms of financial gains or losses (Craninckx & Huyghebaert, Reference Craninckx and Huyghebaert2011), and, more dramatically, in terms of bankruptcies and liquidations? Or does one use subjective evaluations from self-report surveys or interviews (the bulk of academic research), on matters as diverse as the emotional impact on employees (Bansal, Reference Bansal2017; Vuori, Vuori, & Huy, Reference Vuori, Vuori and Huy2018), organizational justice (Kaltiainen, Lipponen, & Holtz, Reference Kaltiainen, Lipponen and Holtz2017; Soenen, Melkonian, & Ambrose, Reference Soenen, Melkonian and Ambrose2017), talent retention (Marks & Vansteenkiste, Reference Marks and Vansteenkiste2008; Zhang, Ahammad, Tarba, Cooper, Glaister, & Wang, Reference Zhang, Ahammad, Tarba, Cooper, Glaister and Wang2015) and commitment or resistance to change (Dorling, Reference Dorling2017; Kavanagh & Ashkanasy, Reference Kavanagh and Ashkanasy2006; Soenen, Melkonian, & Ambrose, Reference Soenen, Melkonian and Ambrose2017)? Staff perceptions of success and failure in contexts of organizational change depend on who you asked, when you asked them, what you asked, how much they knew and what the personal consequences were for them and others (Hughes, Reference Hughes2011; Smollan & Morrison, Reference Smollan and Morrison2019). Leaders' attributions of the success/failure of organizational change in general (Buchanan & Dawson, Reference Buchanan and Dawson2007), and of M&A in particular (Vaara, Reference Vaara2002; Vaara, Junni, Sarala, Ehrnrooth, & Koveshnikov, Reference Vaara, Junni, Sarala, Ehrnrooth and Koveshnikov2014), are often subject to personal agendas and self-serving biases that may conflict with those of other internal stakeholders.

The motivation for the current study was to investigate staff perceptions of the success or failure of an acquisition and the subsequent merging of systems and operations. Given that most scholarly research in M&A appears to be focused on large enterprises, the current study contributes to the literature by exploring accounts of the acquisitions of two small companies by a relatively larger one and how successful they have been from the perspective of staff at various levels in all three companies. It also answers the calls by Buchanan and Dawson (Reference Buchanan and Dawson2007: 669) for ‘polyvocal narratives of organizational change’, by Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy, and Vaara (Reference Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy and Vaara2017) to conduct research that explicates how post-M&A processes, involving both practice integration and socio-cultural integration, unfold over time, and by Vaara (Reference Vaara2002) to examine how success and failure in M&A is socially constructed.

Antecedents of Success and Failure in M&A

Before conducting a review of the antecedents of success or failure in M&A, it is necessary to acknowledge that there are in some ways significant differences between a merger and an acquisition. Many studies refer to both but focus on one, and without explicitly identifying the differences, particularly with regards to the consequences for staff. A merger is generally considered to be a blending of the resources of two partners to enhance the strategic capabilities of each (Muehlfeld, Sahib, & van Witteloostuijn, Reference Muehlfeld, Sahib and van Witteloostuijn2012), and where the new organization will embrace, if not equal ownership, control and contribution, an implicit or explicit agreement among the parties that the needs of both will be attended to. In an acquisition, control over decision-making tends to vest in the acquirer (Cuypers, Cuypers, & Martin, Reference Cuypers, Cuypers and Martin2017), although some autonomy may be granted to the target company (Castro-Casal, Neira-Fontela, & Alvarez-Perez, Reference Castro-Casal, Neira-Fontela and Alvarez-Perez2013; Graebner et al., Reference Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy and Vaara2017).

The processes of integration in both cases may produce negative material and psychological consequences (Cuypers et al., Reference Cuypers, Cuypers and Martin2017; van Knippenberg, van Knippenberg, Monden, & de Lima, Reference van Knippenberg, van Knippenberg, Monden and de Lima2002; Vuori, Vuori, & Huy, Reference Vuori, Vuori and Huy2018), particularly for those who worked for the target company in an acquisition or the smaller or weaker sibling in a merger (Drori, Wrzesniewski, & Ellis, Reference Drori, Wrzesniewski and Ellis2011; Graebner et al., Reference Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy and Vaara2017; Joseph, Reference Joseph2014; Sung, Woehler, Grosser, Floyd, & Labianca, Reference Sung, Woehler, Grosser, Floyd and Labianca2017). Surprisingly, however, after a merger of two universities initiated by a national government, staff surveyed in each tended to believe that those from the other organization dominated (van Vuuren, Beelen, & de Jong, Reference van Vuuren, Beelen and de Jong2010). In an acquisition, where some aspects of the two organizations are ‘merged’ or consolidated, despite (perhaps) the declarations of the acquirer, and the hopes of the target's owners and staff, managers of the bigger sibling tend to have more authority and other forms of power, with potentially deleterious consequences for those previously in the smaller one, including alienation (Bansal, Reference Bansal2017), negative emotions (Vuori, Vuori, & Huy, Reference Vuori, Vuori and Huy2018), conflict (Cohen, Birkin, Cohen, Garfield, & Webb, Reference Cohen, Birkin, Cohen, Garfield and Webb2006; Vaara, Sarala, Stahl, & Björkman, Reference Vaara, Sarala, Stahl and Björkman2012) and exits (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Ahammad, Tarba, Cooper, Glaister and Wang2015). For integration to be successful the retention of key staff members is an important factor, as they hold and can share highly relevant knowledge (Castro-Casal, Neira-Fontela, & Alvarez-Perez, Reference Castro-Casal, Neira-Fontela and Alvarez-Perez2013; Han, Jo, & Kang, Reference Han, Jo and Kang2018).

Many external and internal factors have been attributed to the success or failures of both M&A. With respect to external factors, political agendas, ecological issues (including epidemics and pandemics), economic decline and superior competition can lead to the failure of merged organizations. According to Graebner et al. (Reference Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy and Vaara2017), post-merger integration includes strategic integration (the combination of resources), socio-cultural integration (national and organizational culture, identity, trust and justice) and processes of learning through experience. Strategic decisions strongly contribute to how successful an M&A is and depend on a competent analysis of the external macro and industry environments and of the internal environments of the parties to the M&A (Christiansen et al., Reference Christiansen, Alton, Rising and Waldeck2011; Muehlfeld, Sahib, & van Witteloostuijn, Reference Muehlfeld, Sahib and van Witteloostuijn2012). Although termed strategic by some authors, many of the decisions on post-merger integration are about tactics, policies, procedures and operational practices. Literature on socio-cultural integration attests to the importance of several key human factors and the complex interplay between them. Given that this study concerns perceptions of the processes and outcomes of acquisitions, the next section focuses on these (and other) socio-cultural factors.

Socio-cultural Factors in Post-acquisition Integration

Organizational culture

Many failures of both mergers and acquisitions have been attributed to clashes between the organizational cultures, and the inability of corporate leadership to understand cultural differences, predict the outcomes or take steps to mitigate the negative elements and forge a new, constructive identity that engages most of the actors (Marks & Mirvis, Reference Marks and Mirvis2011; Marks & Vansteenkiste, Reference Marks and Vansteenkiste2008). Organizational culture is a combination of values, assumptions, practices and artefacts that infuse organizational life (Schein, Reference Schein1990). Problems of cultural change occur not only at the psychological level (Friedman, Carmeli, Tischler, & Shimizu, Reference Friedman, Carmeli, Tischler and Shimizu2016; Smollan & Sayers, Reference Smollan and Sayers2009; Tarba, Ahammad, Junni, Peter Stokes, & Morag, Reference Tarba, Ahammad, Junni, Peter Stokes and Morag2019), but also in the formation of new strategies (Cuypers et al., Reference Cuypers, Cuypers and Martin2017) and in the practical aspects of restructuring and integrating policies and systems (Stahl & Voigt, Reference Stahl and Voigt2008; Tarba et al., Reference Tarba, Ahammad, Junni, Peter Stokes and Morag2019). Problems surface in large-scale M&A, where integration is complex and organizational cultures have more diffuse elements, such as in the acquisition of Compaq by Hewlett Packard (Forster, Reference Forster2006), the AOL/Time Warner merger, ‘in what is usually described as the worst merger of all time’ (McGrath, Reference McGrath2015) and Daimler's acquisition of Chrysler (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Carmeli, Tischler and Shimizu2016). However, there is no reason why this cannot be a problem in small-scale M&A where issues of power may also surface (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Birkin, Cohen, Garfield and Webb2006). Differences within organizational cultures can be exacerbated by differences in national cultures, particularly in cross-border M&A (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Carmeli, Tischler and Shimizu2016; Gill, Reference Gill2012; Marks & Mirvis, Reference Marks and Mirvis2011; Melkonian, Monin, & Noordehaven, Reference Melkonian, Monin and Noordehaven2011; Vaara et al., Reference Vaara, Junni, Sarala, Ehrnrooth and Koveshnikov2014). In contrast, Tarba et al. (Reference Tarba, Ahammad, Junni, Peter Stokes and Morag2019) point out that cultural differences may also be complementary and can have positive outcomes if rigid mindsets give way to insight and openness to change, and long-established practices (in either/any of the partners) are subjected to negotiation and reflection. A turbulent merger of two public sector agencies by Barratt-Pugh and Bahn (Reference Barratt-Pugh and Bahn2015) revealed that there were positive and negative perceptions of the new cultural values, stated and practised, partly influenced by the nature of organizational leadership and the management style of the individual supervisor.

Identity

Organizational culture has an implicit (and sometimes explicit) relationship to identity, and, according to Ashforth, Rogers, and Corley (Reference Ashforth, Rogers and Corley2011), identity needs to be studied across and between different levels – individual, social and organizational. Literature on M&A often refers to organizational identity, the extent to which employees feel aligned to their employer, and how this may be shaken by the M&A integration processes and outcomes (Edwards, Lipponen, Edwards, & Hakonen, Reference Edwards, Lipponen, Edwards and Hakonen2017; Graebner et al., Reference Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy and Vaara2017; Sung et al., Reference Sung, Woehler, Grosser, Floyd and Labianca2017). Aspects of identity, such as the name of the organization, uniforms, signage and other artefacts, are considered symbolic and important by some (Schein, Reference Schein1990), and when they change in M&A, identity may be undermined (Joseph, Reference Joseph2014; Rodríguez-Sánchez, Ortiz-de Urbina-Criado, & Mora-Valentín, Reference Rodríguez-Sánchez, Ortiz-de Urbina-Criado and Mora-Valentín2019; Tarba et al., Reference Tarba, Ahammad, Junni, Peter Stokes and Morag2019), or, over time, possibly strengthened. Clark, Gioia, Ketchen, and Thomas (Reference Clark, Gioia, Ketchen and Thomas2010) note the emergence of a transitional identity in analysing the merger of previous industry rivals. Although the spur to merge was partly a perceived threat to the survival of each partner, it took good leadership and communication to eventually create a new culture, a new identity and a stronger financial base.

Other forms of identity are also challenged in M&A contexts. For example, social identity, the sense of communality with a defined group (based on demographics, occupations/professions, departments and other factors), influences the cognitive, affective and behavioural responses to M&A (Kroon & Noordehaven, Reference Kroon and Noordehaven2018; Spoor & Chu, Reference Spoor and Chu2018; Sung et al., Reference Sung, Woehler, Grosser, Floyd and Labianca2017). ‘Us’ and ‘them’ factions and fractures can derail attempts at integration, particularly when differences in status, power and rewards are manifested (Joseph, Reference Joseph2014). Personal identity, a sense of ‘who I am’, and role identity (e.g., leader identity, Xing and Liu, Reference Xing and Liu2016) are also subject to re-evaluation and reconstruction (Ashforth, Rogers, & Corley, Reference Ashforth, Rogers and Corley2011) but have been less studied in M&A contexts, particularly when roles are diminished or disestablished. Mergers can be very stressful, particularly when downsizing occurs (Fugate, Kinicki, & Scheck, Reference Fugate, Kinicki and Scheck2002), and injustice is anticipated or experienced (Melkonian, Monin, & Noordehaven, Reference Melkonian, Monin and Noordehaven2011).

Organizational justice

How fairly people believe they are treated influences their perceptions of the success of an organizational change. Colquitt (Reference Colquitt2001) has separated justice into four dimensions: distributive justice refers to outcomes, procedural justice is concerned with processes, including styles of decision-making and the representation of affected parties, interpersonal justice relates to the sensitivity and dignity with which people are treated and informational justice relates to the fullness, accuracy and timing of how issues are communicated.

Perceptions of various forms of injustice have fuelled many failed attempts of M&A (Graebner et al., Reference Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy and Vaara2017). Justice judgements are not static; as events unfold the perceptions of actors change and impact on emotional reactions (Bansal, Reference Bansal2017), commitment to change (Melkonian, Monin, & Noordehaven, Reference Melkonian, Monin and Noordehaven2011), trust in top management (Kaltiainen, Lipponen, & Holtz, Reference Kaltiainen, Lipponen and Holtz2017) and turnover intentions (Sung et al., Reference Sung, Woehler, Grosser, Floyd and Labianca2017). Perceptions of injustice are more likely to occur among staff of the junior partner in M&A, as Melkonian, Monin, and Noordehaven (Reference Melkonian, Monin and Noordehaven2011) found in their study of the acquisition of KLM by Air France, but may alter over time.

Building trust through leadership and communication

Although trust, leadership and communication are separate constructs, there are cause–effect relationships between them in the M&A field. Perceptions of the role of leaders in M&A have been studied from the perspective of the leaders themselves and of followers. Kavanagh and Ashkanasy (Reference Kavanagh and Ashkanasy2006) found that lack of skill in change management and communication led to negative staff perceptions of the process, lack of trust in management and resistance to the merger. Similarly, Olsen and Solstad (Reference Olsen and Solstad2017) found that when mergers in three industry sectors produced a contrast in professional and managerial logics, the outcomes included perceptions of poor leadership of change, distrust in senior management by middle management. In contrast, Rodríguez-Sánchez, Ortiz-de Urbina-Criado, and Mora-Valentín (Reference Rodríguez-Sánchez, Ortiz-de Urbina-Criado and Mora-Valentín2019) believe that appropriate leadership skills and two-way communication contributed to positive perceptions of how the integration process had been handled, even when the target's name, logo and colours had been removed. In a study of major organizational changes, Holten, Hancock, and Bøllingtoft (Reference Holten, Hancock and Bøllingtoft2020) found that mergers were by far the most prevalent context, with their study unsurprisingly revealing that perceptions of good leadership resulted in more positive change outcomes.

Trust in management is built when followers believe that change leaders are acting with integrity, that they have articulated a clear set of values, demonstrate transparency and do what they promised (Simons, Reference Simons2002). These are elements of authentic leadership (Agote, Aramburu, & Lines, Reference Agote, Aramburu and Lines2016), which requires self-awareness and skills in building relationships and is undergirded by the leadership traits of confidence, optimism and resilience (Avolio & Gardner, Reference Avolio and Gardner2005). Gill's (Reference Gill2012) analysis of two contrasting leadership styles in international M&A (Renault–Nissan and Daimler–Chrysler–Mitsubishi) revealed her belief that the authentic leadership of chairperson Carlos Ghosn led to success in the first merger but was deemed to be missing in the executive responsible for the second merger (with Mitsubishi), which resulted in poor outcomes. Given Ghosn's recent fall from grace, his flight from Japan and his impending court case for alleged fraud, perceptions of his integrity are under intense scrutiny (Denyer, Reference Denyer2020; Tabuchi, Reference Tabuchi2019).

Leadership styles in M&A are key antecedents of success and failure (Barratt-Pugh & Bahn, Reference Barratt-Pugh and Bahn2015). In Xing and Liu's (Reference Xing and Liu2016: 2560) qualitative study of leaders in a range of acquirer and target firms, understanding and respect for organizational cultural differences and clear communication helped to gain the trust and support of followers, with one executive claiming, ‘We did not routinely impose our organizational culture and management style. Now looking back retrospectively, we are delighted to have taken such a strategic action’. The findings of interviews conducted by Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Ahammad, Tarba, Cooper, Glaister and Wang2015) are more ambivalent, with some leaders reporting that they used consultative styles but the majority claiming that authoritative and task-oriented approaches were more successful in the Chinese cultural context.

Summary of the literature and research questions

To summarize the literature on integration processes, although the key socio-cultural factors noted above (organizational culture, identity, justice, trust, leadership and communication), all influence the success of M&A, there are many intersecting relationships between them in the short, medium and long terms. It seems that 14 years after the Air France–KLM merger, staff dissatisfaction in the smaller but more profitable KLM continues to simmer and periodically explode (Nussbaum, Reference Nussbaum2018). In addition, although these micro-processes of M&A (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Carmeli, Tischler and Shimizu2016) play a key role, if the strategy is not appropriate, and/or adverse external factors become dominant, M&A will still fail.

A number of factors motivated the current study. The first is that little research appears to have been conducted on small-scale M&A and an issue worth studying is whether there are differences in the integration processes of smaller entities. The second is that despite the burgeoning field of M&A in New Zealand, a country with a high percentage of small- and medium-sized enterprises (Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment, New Zealand, 2019), few academic studies appear to have been conducted other than Joseph's (Reference Joseph2014) exploration of identity issues in a large-scale banking acquisition. The third factor was noted in the Introduction, the unsatisfactory treatment of definitions of failure in organizational change in general and M&A in particular. The research questions that drive this study are therefore:

- RQ1:

What are the criteria of successful change in the perceptions of managers and employees in an acquiring organization and its targets?

- RQ2:

To what extent do these managers and employees believe that the acquisition they experienced has been a success?

- RQ3:

What factors influence perceptions of success or failure in post-acquisition integration?

Method

The theoretical foundation

Concepts of what constitutes success and failure in M&A may be individually determined but are socially constructed. Vaara (Reference Vaara2002) argues that too few studies focus on the ways in which the success (or failure) of post-merger integration are discursively constructed and that managerial perspectives dominate, at the cost of other voices. In a later study, he and his colleagues demonstrate how attributions of the impact of culture (organizational and national) on M&A performance influence managers to attribute failure to cultural differences rather than to their own weaknesses and errors (Vaara et al., Reference Vaara, Junni, Sarala, Ehrnrooth and Koveshnikov2014). The perceptions of success of leaders of organizational change, and those who manage or implement aspects of the change, may be sustained by self-serving bias, even in the face of contradictory information and the critical judgements of others (Buchanan & Dawson, Reference Buchanan and Dawson2007).

Given the contested nature of how organizational change failure is defined and evaluated (Hughes, Reference Hughes2011; Smollan & Morrison, Reference Smollan and Morrison2019), a new study was initiated to investigate different managerial and staff perceptions of change in one context, M&A. Narratives of change from various perspectives provide access to the thoughts, feelings and behaviours of internal actors (Buchanan & Dawson, Reference Buchanan and Dawson2007), and the case study method is a suitable vehicle for exploring different perceptions of the same organizational events (Yin, Reference Yin2018).

The research site

An opportunity became available to conduct research in a company that had made 10 acquisitions in its history, and three in the 13 months preceding the commencement of this research study. The acquiring company (hereafter called Company A) has its head office in Auckland, on the North Island of New Zealand, with branches in various parts of the country, and provides a range of technology-based services to organizational clients. At a meeting with the CEO and a senior manager in late 2018, it was agreed that one of the acquired targets (Company T1) would provide a suitable site for a study of perceptions of organizational success from the perspective of managers and staff in Company A and Company T1. This was a very small company in the same broad field, acquired in 2014, with only a few employees, including the owner and his wife, and was based in Christchurch on the South Island. Given that Company A had previously relied on contractors to service clients on the South Island, the acquisition of Company T1 would allow it to substantially expand its geographic footprint and exercise more control over its customer relationships, service quality and financial position. The previous owner had been looking to sell the business and retire.

Because the potential pool of participants was low, an additional acquisition (Company T2) was added to the research study. This company, previously a direct competitor on the North Island, had more staff and was located in several towns and cities to the east and south of Auckland, where it also had a branch. Because it had been struggling financially, the owner and CEO had sold the company to Company A and exited the business and industry. For both target companies, the CEOs had negotiated the sale of the business, and although the staff of both had suspected that the businesses would eventually be sold, it had suddenly been announced at a meeting, followed (immediately for some and shortly thereafter for the others) by a meeting with the senior management team of the new owners. One of the first aspects of the takeovers was an announcement by the CEO of Company A that no redundancies were envisaged and that at the operational level not much would change.

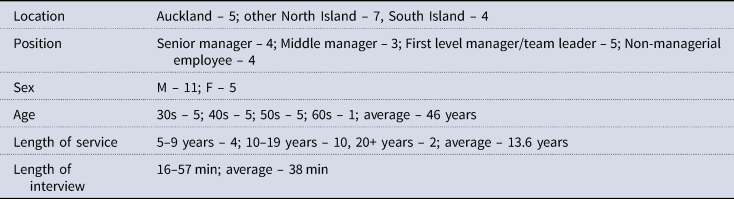

Participants and procedure

Semi-structured interviews were held from January to May 2019, face-to-face in the Auckland office and over telephone for other locations. Interviews were conducted with the CEO, and 15 other managers and employees, including the ex-owner of Company T1 (who had agreed to stay on for a brief transition period but who ended up staying for 4 years, finally retiring shortly after the interview). Some of the staff who had originally been in one of the three companies had subsequently voluntarily moved to another location and their understanding of the acquisition was partly derived from the initial location they had been working in, and partly from their subsequent experiences as aspects of the integration became more manifest. Participant details can be found in Table 1. The interviews were recorded, and transcriptions and a summary report of the research were sent to each participant.

Table 1. Participant details

Most participants were asked the same questions but there were variations depending on the roles and locations of the participants. They were asked how the processes and outcomes of the acquisition(s) had affected them and others (some of the head office staff were involved in both acquisitions), whether they had initially thought that the change would be successful and why, whether their perceptions has changed over time, whether they or others had resisted the change, what constituted a successful acquisition in general, whether they believed the acquisition(s) had been successful and on what grounds. They were also asked how well the process of communicating and integrating the acquisition had been managed and what might have been done better.

Data analysis

Analysis of the data went through several phases, using both thematic analysis and template analysis. Thematic analysis is a general approach to investigating qualitative data on social phenomena that involves the identification of themes, ‘some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set’ (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006: 82). Thematic analysis begins with a repeated reading of the material and is followed by the identification of initial codes, the searching for themes, reviewing and defining the themes, and possibly creating sub-themes. It has been used across a wide variety of disciplines, including psychology (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; Clarke & Braun, Reference Clarke and Braun2017), management (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2015) and organizational change (Andersen, Reference Andersen2018). Template analysis is a more structured form of thematic analysis, whereby a priori codes, emanating from the literature or the data, can be used to investigate the phenomena being researched, whereas balancing structure with flexibility in interpretation of the data (Brooks, McCluskey, Turley, & King, Reference Brooks, McCluskey, Turley and King2015; King, Reference King, Symon and Cassell2012; King & Brooks, Reference King and Brooks2017). Both thematic and template analysis allow for deductive and inductive elements (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, McCluskey, Turley and King2015). Nvivo 12, a computer-assisted qualitative analysis application, was used to facilitate the analysis process and to support the interpretive and reflexive thinking skills of the researchers (Eriksson & Kovalainen, Reference Eriksson and Kovalainen2008; Silverman, Reference Silverman2017). Nvivo made the administration, coding, cross-referencing and reporting of data more efficient.

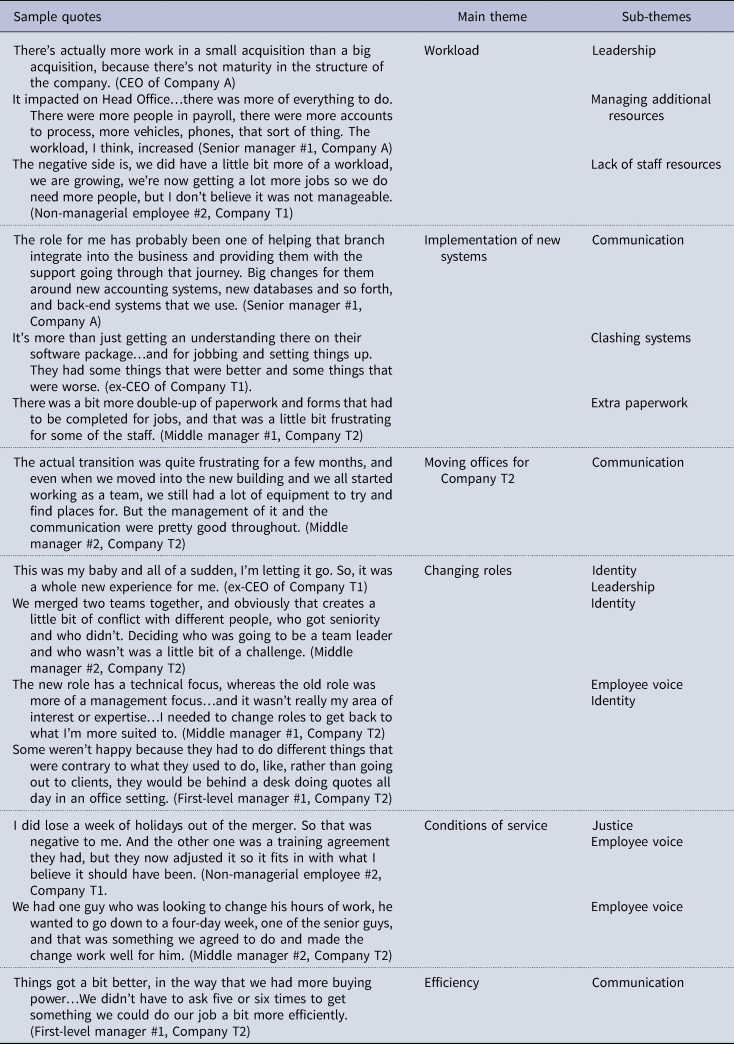

In the current study, the transcripts were read though several times by both researchers and tables were created that addressed the key interview questions, which became the codes. Thus, although still part of an interpretive approach, this phase was largely deductive. Five tables were created for these codes, relating to the Impact of the acquisition(s) on the participants and others (Table 2), Resistance to change/support for change (Table 3), Criteria of the success or failure of an acquisition in general (Table 4), the Success or failure of the acquisition by Company A of Company T1 and/or Company T2 (Table 5) and How well the process had been managed and what might have been done better (Table 6). Selected quotes from the transcripts that fitted the codes and the main themes within them were imported into the tables. For an example of the process, increased Workload was identified as one theme of the code, Impact on the participant and others (as part of the transition or the aftermath of the acquisition).

Given that much of the literature on M&A integration deals with constructs such as organizational culture, identity, organizational justice, trust, leadership and communication, it was expected that some of these (and others) might surface in the interviews. Therefore, the next phase of data analysis focused on the issues and constructs that emerged. The key constructs from the literature formed sub-themes of the data analysis, which also allowed for the infusion of a variety of issues narrated by the participants. For example, within the code of Impact on the participant and others (Table 2), and the theme of Workload, one sub-theme related to the key construct of Leadership and two related to practical aspects, such as managing extra resources at the head office level (Company A), and coping with business growth with a lack of staff resources at the local level (Company T1).

Findings

Impact on the participants and others

It was reassuring to all staff in the target companies that no jobs would be lost, rather, that extra opportunities would likely arise, and that not much would change in the ways in which they did their jobs. It is not surprising that those affected by an organizational change consider how it has impacted on their own jobs, but many employees, including leaders at various levels, do observe, and may be concerned about the impact on others (see Table 2). Firstly, workload increased for some in the acquirer (Company A) and the targets (Company T1 and Company T2), as they needed to navigate their way through the transition process and the adoption of Company A's systems of job orders, health and safety, accounts and IT. Company A staff therefore needed to provide extra training. This produced an element of frustration for many staff, particularly for those in the newly acquired businesses who believed that some of their systems were superior, a point acknowledged by Company A management. In one of the locations of Company T2, their staff and that of Company A, a former competitor in that part of the North Island region, had to move to new offices, causing considerable inconvenience in the transition phase. The allocation of roles in a revised structure was particularly evident in this unit and the Auckland-based operations office. Target staff were pleased that Company A had considerably more financial resources, which would add to the efficiency and growth of their own operations.

Table 2. Impact of the acquisition on the participants and others

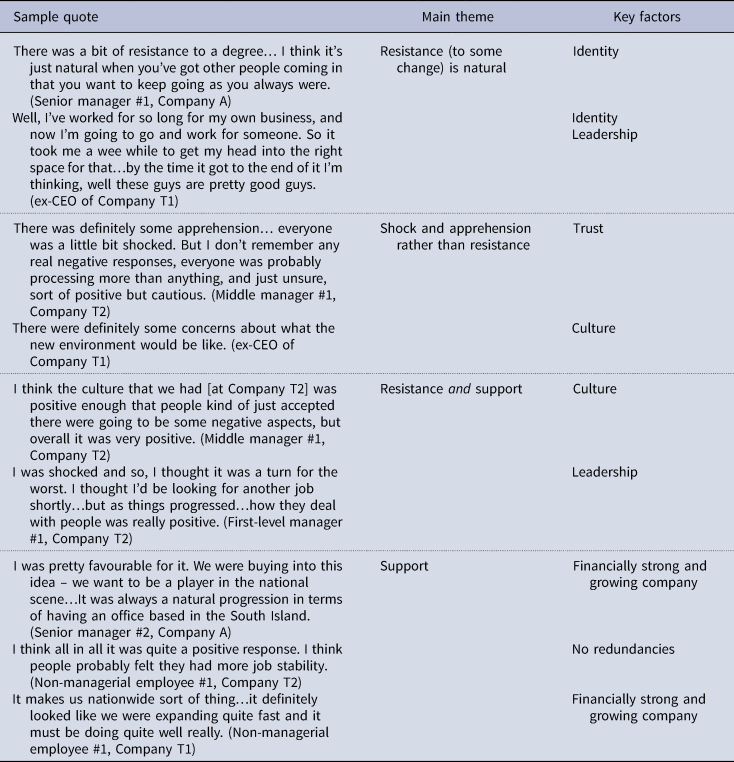

Resistance to change/support for change

Despite being initially stunned by the sudden communication of the acquisitions, and the considerable anxiety as to the potential consequences it engendered, the swift revelation that there would be no redundancies and few changes to people's jobs, mitigated many people's concerns in Company T1 and Company T2. Most staff in the target companies had not resisted the takeover as such, but only some aspects that they found frustrating as systems were integrated. In time, most of the anxiety and frustration abated as the new systems and practices were operationalized. Initial encounters with the Company A leadership team, and the organizational culture they explicitly outlined were generally very positively perceived. The prospect of a stronger financial foundation also elicited support (Table 3).

Table 3. Resistance to change/support for change

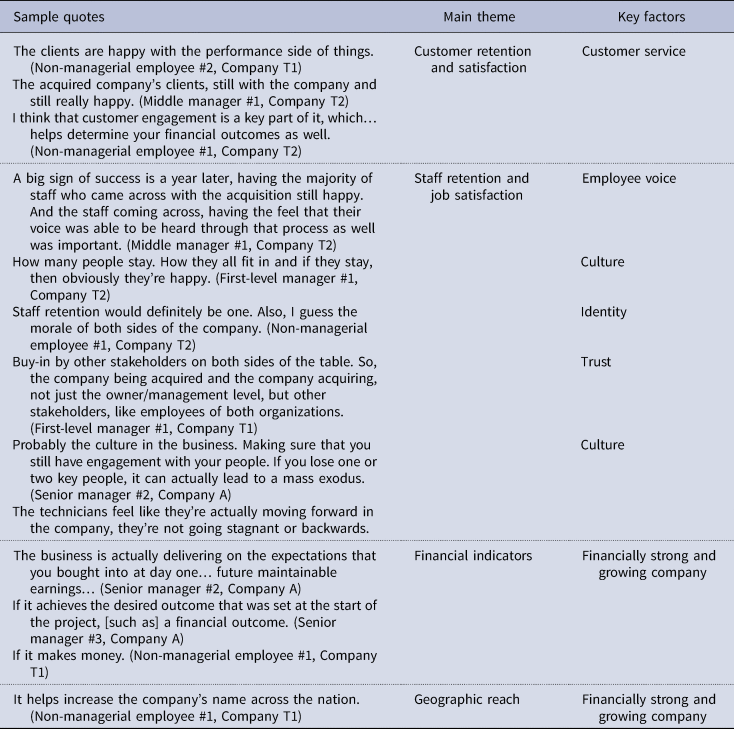

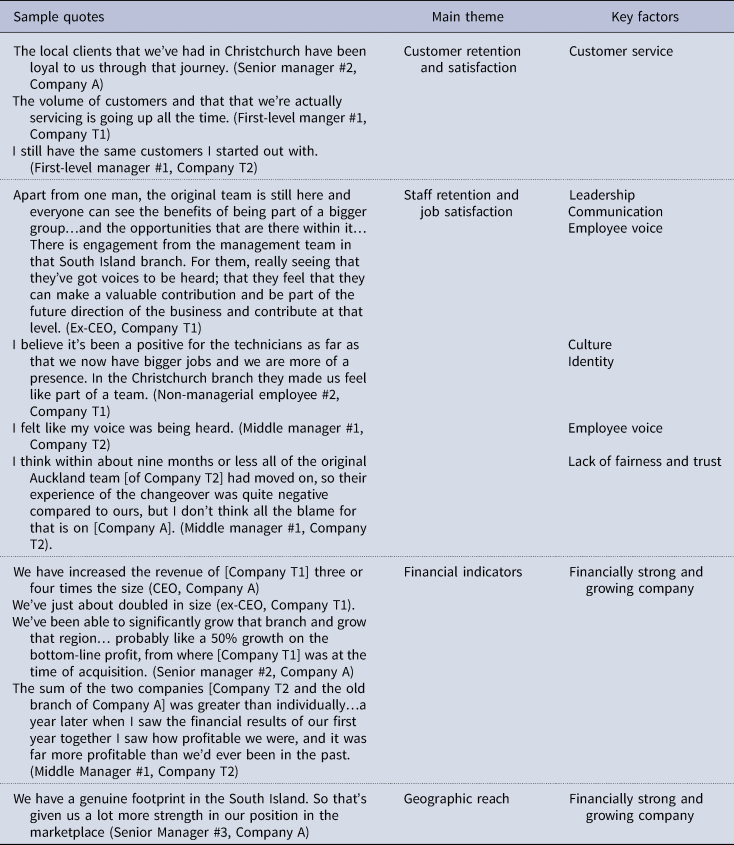

Indicators of the success or failure of an acquisition

Managers and staff from Company A and those from the acquired companies were first asked to identify their criteria of success of an acquisition in general (see Table 4), then for the application to their own experience in the enlarged Company A (Table 5). The retention and satisfaction of customers and staff, and a stronger financial foundation were the most common features of hypothetical considerations and practical applications. Some responses were more abstract, such as the reference to the achievement of objectives. The prime goal of Company A was to expand its geographic scope by acquisitions, and thereby enhance its financial strength, and the hopes of most staff focused on job retention, job satisfaction and career growth. Most participants believed that these objectives had been achieved.

Table 4. Indicators of the success or failure of an acquisition in general

Table 5. Indicators of the success of the acquisitions

Managing the process of the acquisition

In answer to the questions, ‘How well was the process managed?’ and ‘What could have been done better?’, participants from the leadership team at Company A believed they had created a constructive organizational culture over years, had acted with integrity in the two acquisitions (and those that preceded and followed them), and that they had in mind the needs of staff in the acquired company. The CEO of Company A was critical of change management in large-scale M&A, asserting that, ‘Integration is a journey, and I think what big business does so wrong, multi-nationals, of acquisition, they roll in like a steam train and change everything’. He acknowledged that change took time in M&A processes and that a slower pace would lead to much better results. Staff in Company T1 (including its ex-CEO who remained for 4 years as the South Island regional manager), were mostly content with the way Company A had handled the communication of the acquisition and the changes that had flowed from the integration. Staff in Company T1 trusted their own manager, the ex-CEO, whereas those in Company T2 were, perhaps surprisingly, generally not unhappy with the sudden announcement of the news. The confidential nature of M&A, the competitive nature of their industry and the need to lessen possible uncertainty and the attendant anxiety, were widely accepted as valid reasons. Nevertheless, there were some aspects of the initial process that some found trying, for example training sessions on new systems before staff in the target companies could process the major change that had just been communicated (Table 6).

Table 6. How well the process was managed and what might have been done better

Socio-cultural factors in post-acquisition integration processes

In the second phase of data analysis, participants' comments were sought that contributed to a deeper understanding of the processes and outcomes of an acquisition, specifically organizational culture, identity, organizational justice, trust, leadership and communication – and other issues that emerged from the interviews. These constructs are indicated in the tables as sub-themes.

Organizational culture was mostly an issue that was raised by senior leadership team members in Company A. They were proud of the culture that had been created in the original company and sought to infuse it, without disturbing the social equilibrium, into the acquired companies. The key elements of the culture, identified by the CEO were a focus on customers, service quality and employee engagement: ‘The clients follow the people, and if we engage the people and really integrate them into our culture well in our organisation, then we've got a really great, successful outcome’. Regarding the pre-acquisition phase, he noted the importance of cultural alignment and maintained that this was one reason for the successful outcomes of the takeover of Company T1. The initial meetings with staff in Companies T1 and T2 had a strong focus on not only the culture of Company A but also the strengths of the acquired company. Another senior leader paid tribute to the staff of Company T1 and particularly its ex-CEO and current manager of the South Island branch:

A lot of those guys are setting the tone as well in the organization, in terms of the culture, which is really good. And what we want is to hear from those guys is the standards that they work to, standards of behaviour, conduct, and those kinds of things. I think [the ex-CEO] has set a really good imprint in those guys. (Senior manager #2, Company A)

Views in the acquired companies were also positive about cultural integration and also indicate allayed concerns about various forms of identity. For one person, it was social identity:

I guess probably my major concern when we had the acquisition was what the culture was like, being a bigger company. You were always worried that you were just going to be a number and there wasn't going to be much team atmosphere…We were a pretty tight-knit group at Company A2 for a long time. But no, I think they made a bit of an effort to try and get everyone involved and integrated. (Middle manager #2, Company T2)

The ex-CEO of Company T1, which had borne his name for many years, and which was therefore an element of his personal and organizational identity, was wistful about the change of the name to Company A but was nevertheless happy that, ‘We sort of just transitioned and really, all of the team in Christchurch, we put on different shirts with a different name on it, and it was just business as usual’.

Communication and good leadership were key elements of the formation of trust between Company A and the two acquired companies. The tone was set at the initial meetings between the leadership team of Company A and the target companies. Senior Manager #2 of Company A noted that, with regular communication during the integration, ‘There's a build-up of trust that happens over time if you go through that journey’. The use of newsletters celebrating the acquisition of the two companies and featuring stories about them, helped to cement relationships and foster a common organizational identity. The same manager noted it was important that, ‘For them, really seeing that they've got voices to be heard, that they feel that they can make a valuable contribution and be part of the future direction of the business and contribute at that level’. This echoed a statement by Middle manager #1, Company T2, ‘My voice was heard’.

It was interesting, as noted earlier, that there was little dissatisfaction about fairness issues when the CEOs of Company T1 and Company T2 had suddenly announced the acquisitions of their companies, followed very shortly by the appearance of the leadership team of Company A. Organizational justice for staff in these companies was more about distributive justice, regarding issues of pay, training, leave and the use of resources, most of which appeared to have been satisfactorily resolved within a few months.

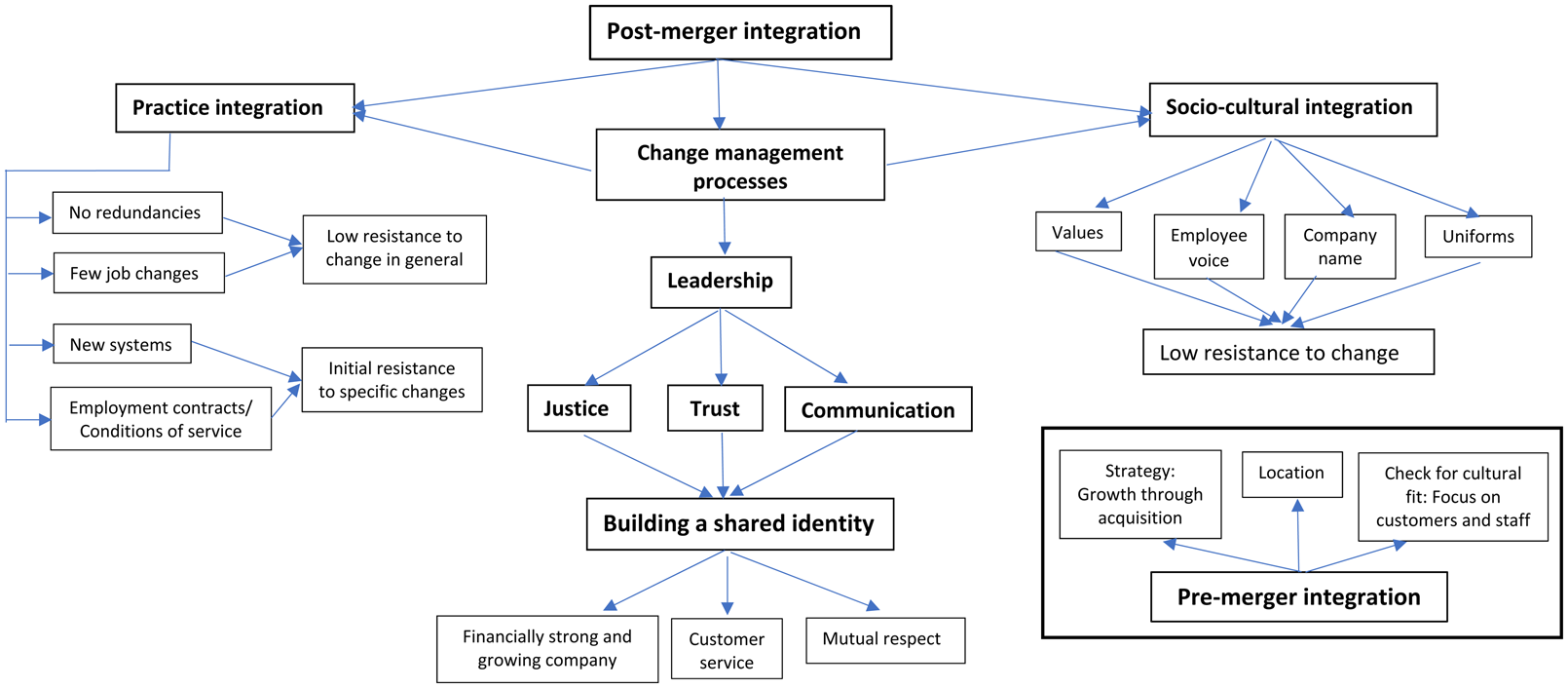

Figure 1 is a thematic map that was developed to graphically depict the relationships between the various constructs unpacked in the literature review and key aspects presented in the findings. It emerged both from the Nvivo analysis of the data and the combined analyses of the researchers. Pre-merger integration processes are included in the bottom-right corner to indicate the context of the study. Post-merger integration processes are separated into practice integration and socio-cultural integration. The former relates to changes in roles, tasks and systems, and how these elements contributed to support for change or resistance to it, whereas the latter refers to embedding values and cultural symbols (such as uniforms and company name) and how these led mostly to low resistance to change and decent levels of support. Linking the two forms of integration are the change management processes, based on good leadership, established through practices leading to perceptions of fairness, effective communication and foundations of trust. These in turn, led to a shared identity in the enlarged company, one of financial fitness, customer service and mutual respect.

Figure 1. Thematic map of findings.

Discussion

The findings reveal that the two acquisitions by Company A were considered successes by all participants, but with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Their hypothetical criteria of an acquisition, which largely concerned customer retention, financial strength and staff retention and engagement, were matched by the perceived outcomes. The initial reservations of some of those in the acquired companies, based mostly on the anxiety derived from uncertainty, soon diminished. Uncertainty about one's employment status has bedeviled many organizational changes, particularly when redundancies occur in the M&A field (Melkonian, Monin, & Noordehaven, Reference Melkonian, Monin and Noordehaven2011; Sung et al., Reference Sung, Woehler, Grosser, Floyd and Labianca2017) and leads to considerable stress for both its victims and survivors (Fugate, Kinicki, & Scheck, Reference Fugate, Kinicki and Scheck2002). The immediate reassurance by Company A leaders that no downsizing would occur came as a relief to those in the target companies, but lack of clarity about roles in Company T2, was an issue for some staff, particularly because it had previously been a competitor. Although negative emotions did arise, particularly frustration with the integration of systems, they did not ultimately lead to negative outcomes, in contrast with the many negative emotions of M&A detailed by Vuori, Vuori, and Huy (Reference Vuori, Vuori and Huy2018) or the alienation noted by Bansal (Reference Bansal2017).

Many sources of M&A failure have been attributed to incompatible organizational cultures (e.g., Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Carmeli, Tischler and Shimizu2016; Kavanagh and Ashkanasy, Reference Kavanagh and Ashkanasy2006; Marks and Mirvis, Reference Marks and Mirvis2011; Stahl and Voigt, Reference Stahl and Voigt2008; Tarba et al., Reference Tarba, Ahammad, Junni, Peter Stokes and Morag2019). In the current study, the CEO had indicated that cultural alignment was researched before acquisition decisions were made and integrating cultures would be a priority afterwards. The expressed desire by Company A leadership to retain and engage the staff of the acquired companies helped to assuage feelings of alienation. Allowing some existing practices of Company T1 and Company T2 to continue in the integration phase strengthened the cultural foundations of the merged companies. Cultural artefacts (Joseph, Reference Joseph2014; Schein, Reference Schein1990), such as the name of the company, uniforms and signage have strong emotional connotations (Kroon & Noordehaven, Reference Kroon and Noordehaven2018; Tarba et al., Reference Tarba, Ahammad, Junni, Peter Stokes and Morag2019), but it was noticeable that the ex-CEO of Company T1 quickly adapted himself to the new situation and continued long after as the South Island branch manager, contrary to his own stated intentions of early retirement and the expectations of others.

Identity is often threatened during M&A when the acquirer or the senior partner in a merger exerts more control (Drori, Wrzesniewski, & Ellis, Reference Drori, Wrzesniewski and Ellis2011). Organizational identity, a collective sense of who we are as an entity (Ashforth, Rogers, & Corley, Reference Ashforth, Rogers and Corley2011), is usually a more intense concern for the target staff. This can lead to a fragmentation of organizational identity into competing social identities – ‘us and them’ (Stahl & Voigt, Reference Stahl and Voigt2008). Those who previously had power in an older regime, will probably resent its loss when significant change take place and this is a particularly likely occurrence in M&A for junior partners (van Knippenberg et al., Reference van Knippenberg, van Knippenberg, Monden and de Lima2002; van Vuuren, Beelen, & de Jong, Reference van Vuuren, Beelen and de Jong2010) or those in acquired companies, who believe they have been marginalized. There was little evidence of this in the current study and even the ex-CEO of Company T1 graciously accepted his new role. A comment by one participant (Middle manager #1, Company T2) that his views had been heard, and treated with respect, conveyed not only a sense of a new organizational identity but also one of role (leader) identity (Xing & Liu, Reference Xing and Liu2016) and an intimation of procedural and interpersonal justice.

Of the four forms of organizational justice conceptualized by Colquitt (Reference Colquitt2001), staff of the acquired companies in the current study indicated that the outcomes, with some minor exceptions were considered fair (distributive justice); processes of inclusion in decision-making of the acquisitions (a facet of procedural justice) were not used, but, in the context of a take-over, were not believed to be necessary; information about post-merger processes and outcomes was immediately given (informational justice); and throughout the period of consolidation, participants uniformly believed they were treated with respect and consideration (interpersonal justice). Previous studies of M&A have shown how relevant perceived fairness is to the success of integration (e.g., Bansal, Reference Bansal2017; Kaltiainen, Lipponen, & Holtz, Reference Kaltiainen, Lipponen and Holtz2017; Melkonian, Monin, & Noordehaven, Reference Melkonian, Monin and Noordehaven2011).

Trust in Company A management was built through good leadership and effective communication. Participants in Company T1, in particular, who continued their largely unchanged jobs under the management of their ex-CEO, indicated how trust in him over many years led to anticipatory trust in the leadership of Company A. It seemed that authentic leadership styles, based on integrity and transparency, together with what appeared to be the engaging and inclusive culture of Company A, contributed to commitment to the enlarged company. Although the CEO of Company T2 had immediately exited the company, participants from its various locations spoke of trust in Company A's leadership, both in terms of effective management and commitment to staff retention and job satisfaction. Authentic leadership (Gill, Reference Gill2012) and appropriate forms and styles of communication (Kavanagh & Ashkanasy, Reference Kavanagh and Ashkanasy2006; Rodríguez-Sánchez, Ortiz-de Urbina-Criado, & Mora-Valentín, Reference Rodríguez-Sánchez, Ortiz-de Urbina-Criado and Mora-Valentín2019) contribute to building trust in M&A processes. Allowing considerable autonomy to acquired companies, considered by some to be the opposite of integration (see Graebner et al., Reference Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy and Vaara2017), may help to minimize the impact of the differences in organizational cultures in M&A (Tarba et al., Reference Tarba, Ahammad, Junni, Peter Stokes and Morag2019). In the current study, granting a measure of autonomy to the acquired companies, outside of IT-based systems (including accounting, HRM and client orders), enhanced two-way trust. Going even further was allowing the continued use of some techniques preferred by Company T2, which were later used by Company A as they were judged superior, a concept neatly captured by Cuypers et al. (Reference Cuypers, Cuypers and Martin2017) in their article aptly titled, When the target may know better. Granting autonomy also helps to retain staff, and aid in integration, findings reported elsewhere (Castro-Casal, Neira-Fontela, & Alvarez-Perez, Reference Castro-Casal, Neira-Fontela and Alvarez-Perez2013; Graebner et al., Reference Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy and Vaara2017).

Although it is not unexpected that leaders of organizational change frame the outcomes in glowing terms (Buchanan & Dawson, Reference Buchanan and Dawson2007), partly to burnish their own self-esteem and role identities (Xing & Liu, Reference Xing and Liu2016), the many voices presented in the current study reinforce the views of the senior leadership team of the acquirer, Company A, that these two acquisitions had been successful.

Limitations and Further Research Directions

The current study has shown how a variety of inter-locking factors led to positive perceptions of managers and employees of the processes and outcomes of two acquisitions. There are naturally several limitations which lead to the need for more research. First, although the current study has provided some rich insights, the specific contexts of the acquisitions leave a number of questions unanswered. Context is always relevant in empirical studies of M&A (Graebner et al., Reference Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy and Vaara2017). For example, many studies of M&A refer to large-scale mergers (e.g., Forster, Reference Forster2006; Gill, Reference Gill2012; Melkonian et al., Reference Melkonian, Monin and Noordehaven2011) and an aspect not satisfactorily explored is the micro-processes of small-scale M&A. Company T1 had only a few employees when it was acquired and was in one location. Although Company T2 had more staff and was in several locations, it was still a small company. In small organizations, communication is easier, the nature of sub-cultures is less apparent and leadership is more visible than in the multi-layered hierarchies of large companies. Research into the effects of company size, both of the acquirers and targets, would help close this gap. In the context of the current study, the relatively small number of participants also indicates that a wider range of responses may have been forthcoming if Company A had granted access to staff in the other acquired companies, even though they too were limited in number.

Second, the current study was a retrospective review of processes (4 years after the acquisition of Company T1 and 2 years after that of Company T2), but with current outcomes also considered relevant. M&A integration is best researched longitudinally (e.g., Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Lipponen, Edwards and Hakonen2017; Fugate, Kinicki, & Scheck, Reference Fugate, Kinicki and Scheck2002; Soenen, Melkonian, & Ambrose, Reference Soenen, Melkonian and Ambrose2017), as it depicts, inter alia, trajectories of identity, trust in leaders and emotional engagement. For instance, Joseph (Reference Joseph2014) found that markers of successful integration in a bank acquisition, such as cohesion, communication and social identity, improved over a period of 7 months. It would have been interesting had that study been extended to the period when the acquired company's name, colours and other cultural artefacts (Schein, Reference Schein1990) had finally been extinguished. Over time, new factors become relevant, promises are kept or broken (Simons, Reference Simons2002), expectations are not met or exceeded, and new factors impinge on old memories, such as more acquisitions, new strategies, changing leaders and emerging cultures and identities.

Third, the outcomes of the acquisitions were mostly benign – geographic expansion for the acquirer and better resources and job security for the targets – where the roles of the latter were not significantly changed. It might have been different had there been redundancies, a frequent outcome of M&A and one with stressful consequences (Fugate, Kinicki, & Scheck, Reference Fugate, Kinicki and Scheck2002). Further studies could therefore unpack how leadership skills produce trust and organizational identity when negative outcomes are anticipated or experienced.

Fourth, there were no explicit questions for participants about some of the constructs in this paper (e.g., organizational culture, identity and organizational justice). Had these issues been raised, a wider range of responses would have been forthcoming.

Implications for Practice

Although the focus of this paper is on post-merger integration, owners and managers need to be aware of the range of well-documented issues on pre-merger integration, for example, assessing cultural fit before a merger/acquisition is finalized (Tarba et al., Reference Tarba, Ahammad, Junni, Peter Stokes and Morag2019) and understanding how M&A affects identity (Graebner et al., Reference Graebner, Heimeriks, Huy and Vaara2017). During the post-merger integration phase, if managers act as fairly as circumstances allow (Kaltiainen, Lipponen, & Holtz, Reference Kaltiainen, Lipponen and Holtz2017) and communicate effectively with staff (Rodríguez-Sánchez, Ortiz-de Urbina-Criado, & Mora-Valentín, Reference Rodríguez-Sánchez, Ortiz-de Urbina-Criado and Mora-Valentín2019), trust will grow (Joseph, Reference Joseph2014).

The results of the current study point to the importance of these factors in creating a successful organization after the merger. That the acquiring company retained most of the staff and customers of the two acquired companies is testimony to the skill and integrity with which they planned and executed the mergers. Managers in acquired companies also have very important roles to play, often remaining the conduits through which much communication is channelled, as Marks and Vansteenkiste (Reference Marks and Vansteenkiste2008) found in their study. Although they may not be initially happy with post-merger changes (in common with those in the acquiring company), they need to be appropriately made aware of the need for their support.

Conclusions

This study has contributed to the literature on post-merger integration in M&A in particular, and on change management more generally, by exploring the perceptions of managers and employees in the acquiring and target companies. One study of successful acquisitions obviously cannot ‘disprove’ the allegations that most M&A fail (Christiansen et al., Reference Christiansen, Alton, Rising and Waldeck2011; Jacobs, van Witteloostuijn, & Christe-Zeyse, Reference Jacobs, van Witteloostuijn and Christe-Zeyse2013), as do other forms of change management, an issue disputed by Hughes (Reference Hughes2011) and Smollan and Morrison (Reference Smollan and Morrison2019). It does reveal, however, that good leadership, communication and fairness builds trust in M&A and helps to create a stronger organization where staff retention and motivation are high and financial outcomes are positive. From theoretical and practical perspectives, leaders of M&A who pay attention to both practice integration and socio-cultural integration, are able to reduce initial resistance to change and to later increase employee commitment to an organization with a shared identity.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Dr. Roy K. Smollan is a Senior Lecturer in Management at the Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand. His research interests lie in the fields of organizational change, organizational culture, organizational justice, emotions at work, stress, trust, leadership and office space. He has been published in a variety of journals in organizational change, organizational behaviour, human resource management and employment relations.

Chris Griffiths is a senior manager in a large New Zealand organization and has had over 25 years' experience in managerial roles in various organizations across the manufacturing and service sectors. He has an MBA and is a PhD candidate at the Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand. His research interests are in aspects of inclusion within an organization.