Background

Hurricane Dorian made landfall on the island of Abaco in the Bahamas as a Category 5 storm with wind speeds greater than 185 miles per hour on September 1, 2019. Reference Avila, Stewart and Berg1 The storm then spent 48 hours over the island of Grand Bahama, moving at 1 mile per hour, and inflicted damage reported to cost over USD 3.4 billion. Reference Avila, Stewart and Berg1,2 Over 70 people were confirmed dead, and more than 200 reported missing. Reference Avila, Stewart and Berg1,2 The destruction left 29 500 people homeless. 2 The Rand Memorial Hospital (RMH), the only government-funded acute care hospital on the island of Grand Bahama, suffered significant flooding damage and subsequent mold overgrowth to roughly 80% of its infrastructure. Following the hurricane, RMH received assistance from the international community through various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and partnerships with private healthcare systems on the island to provide additional sites for patient care, including a field hospital. 2

On March 15, 2020, the first COVID-19 patient was diagnosed in the Bahamas. 3 The ensuing pandemic created a significant challenge to a healthcare system still recovering from the worst storm in its history. With RMH under renovation, isolating, testing, and housing these cases were problematic. Healthcare workers were managing care in disaster conditions for 6 months prior to the start of the COVID-19 crisis. Thus, preparing for and managing patients in a pandemic further strained healthcare workers already near the point of breaking.

Within the last 10 years, multiple global disasters have been studied with a focus on the mental health and resilience of those charged with responding in times of crisis. Studies on residents of the United States Gulf region have found that cumulative disasters can influence physical and mental health. Reference Lowe, McGrath and Young4–Reference Hugelius, Adolfsson and Örtenwall6 In 2019, a systemic review of the literature found that depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) were the most studied outcomes in medical responders. Reference Naushad, Bierens and Nishan7 The investigators noted that lack of social support and communication, maladaptive coping, and lack of training were significant risk factors for developing adverse psychological outcomes across all types of disasters. Reference Naushad, Bierens and Nishan7 Burnout, PTSD, and compassion fatigue have been studied in healthcare workers in various settings. Reference Naushad, Bierens and Nishan7–Reference Epstein, Haizlip and Liaschenko10 The COVID-19 pandemic has seen a surge in research on the mental health status of medical providers due to multiple challenges, such as limited personal protective equipment (PPE), overcrowding of emergency rooms, and intensive care units (ICUs), as well as wards with critical cases, and staffing shortages. Reference Rabow, Huang and White-Hammond9,Reference Jafari, Ebadi and Khankeh11–Reference Gustavsson, Juth and Schreeb16

Systemic problems within healthcare systems that impact patient care can be morally challenging for healthcare providers. Moral Distress (MD), a concept initially described in nurses in 1984, is defined as “the inability of a moral agent to act according to his or her core values and perceived obligations due to internal and external constraints.” Reference Jameton17 Current studies have looked at MD effects on the mental health of disaster responders and most recently, healthcare providers during the pandemic in various disciplines, to determine interventions to improve mental resilience. Reference Gustavsson, Arnberg and Juth8,Reference Gustavsson, Juth and Schreeb16,Reference Spilg, Rushton and Phillips18,Reference Fagerdahl, Torbjörnsson and Gustavsson19 Unresolved MD can create a struggle within the individual that can wear away at personal ethics, leading to burnout and mental distress. Reference Gustavsson, Arnberg and Juth8 This can have long-term consequences for organizations due to increased sick leave and turnover rates of staff. Reference Gustavsson, Arnberg and Juth8 Understanding the concept of MD can assist healthcare leaders in creating stronger organizational cultures that can mitigate its impact. Reference Epstein, Haizlip and Liaschenko10,Reference Hertelendy, Gutberg and Mitchell20 Emergency medical professionals work in a high-stress, high-stakes environment due to the critical presentation of the population they serve. The added burden of multiple disasters can further exacerbate mental distress in this healthcare population. The Accident and Emergency (A&E) physicians, nurses, and Emergency Medical Services (EMS) staff at RMH had a unique experience of providing care during the aftermath of Hurricane Dorian and again, 6 months later through the COVID-19 pandemic. During this time, they also experienced negatively impactful events such as loss of property and loved ones. The primary objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of Moral Distress in Accident and Emergency (A&E) physicians, nurses, and EMS staff at RMH after responding to consecutive disasters. Secondary objectives include determining the impact of Hurricane Dorian & COVID-19 on MD in this population and its associated sociodemographic factors. Determining the prevalence of MD in this population can lead to the development of policies that support healthcare workers’ well-being and enhance the capacity of the healthcare system to respond to consecutive disasters.

Methods

Study Design

This is a descriptive, exploratory, cross-sectional observational study that utilized a 3-part survey through REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA), a secure web application for building and managing online surveys. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health (MOH) (Protocol# MROS/161122/QQC). Approval was also given by the combined committee of the Public Hospitals Authority (PHA) and the University of the West Indies (UWI) (PHA/31/1-B-2) in the Bahamas, as well as the Internal Review Board (IRB) of the Beth Israel Deaconess Center (BIDMC) (Protocol#2023P000011). Before beginning the survey, informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Study Population

The inclusion criteria for the study population were physicians and nurses in the A&E Department of RMH, and EMS staff who provided care during, and in the aftermath of Hurricane Dorian as well as the COVID-19 pandemic from September 2019 to March 2023, and consented to complete the survey. Healthcare personnel who did not work through Hurricane Dorian and the COVID-19 pandemic and did not consent or did not complete the survey, were excluded.

Procedure

The survey was emailed to the study population on March 15, 2023, and was re-sent 2 weeks later to non-responders. This was a 3-part survey. The first section collected baseline sociodemographic factors, the second section asked questions regarding their experience with Hurricane Dorian and COVID-19, and the final section consisted of a modified Moral Distress scale for healthcare professionals. The Measure of Moral Distress for Health Care Professionals (MMD-HP), a 27-item scale used by health professionals in adult and pediatric critical, acute, or long-term acute care settings, was revised to 18 questions for this study to reflect the cultural and situational experiences of the study population, using a 5-point Likert scale to rate the severity level of distress. Reference Epstein, Whitehead and Prompahakul13 Once the survey was complete, the data collected was stored in REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA), a secure encrypted data management program.

Data Analysis

Each of the 18 questions in the Moral Distress Scale (MDS) was rated on the Likert scale (0 – Q4) to reflect distress severity levels: none, very mild, mild, and moderate, as well as severe. The scores for each question were summed to reflect the overall moral distress score for each participant, which had a possible range from 0 to 72, with higher scores being associated with more severe distress. Reference Epstein, Whitehead and Prompahakul13 To describe this quantitative summation of moral distress in a clinically meaningful way, the total score was broken down into 4 categories: very mild (0 – 18), mild (19 – 35), moderate (36 – 53), and severe (54 – 72). The MDS questions included 4 categories: Ethical challenges, Lack of Resources, Pressure from External Forces, and Staffing challenges to determine the aspects of patient care the participants found challenging.

Negative experiences from Hurricane Dorian were a composite factor that comprised the following 3 experiences: worked in the A&E in the immediate period that Hurricane Dorian struck, lost property due to Hurricane Dorian, and lost a loved one due to Hurricane Dorian. Negative experiences from COVID-19 were a composite factor that comprised the following 3 experiences: infected with the COVID-19 virus, quarantined due to contact with the COVID-19 virus, and losing a loved one due to the COVID-19 virus. One participant was excluded from this composite due to not working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Negative experiences from both Hurricane Dorian and COVID-19 were a composite factor that comprised all 6 experiences.

The data was exported and analyzed using the SPSS Statistical Analysis software package version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Continuous variables like age and Moral Distress Scale scores were assessed for normality using histograms and the Shapiro-Wilk test and expressed as mean and standard deviation. For categorical variables such as occupation, frequencies and percentages were calculated. Comparisons between parametric continuous variables were carried out with an independent t-test and 1-way analysis of variance, with significance set at P < 0.05. For inferential statistics, multivariate analysis and logistic regression were used to determine associations between sociodemographic factors and the occurrence of Moral Distress as well as the associations of Moral Distress and Hurricane Dorian and or COVID-19 experiences.

Results

Socio-Demographics

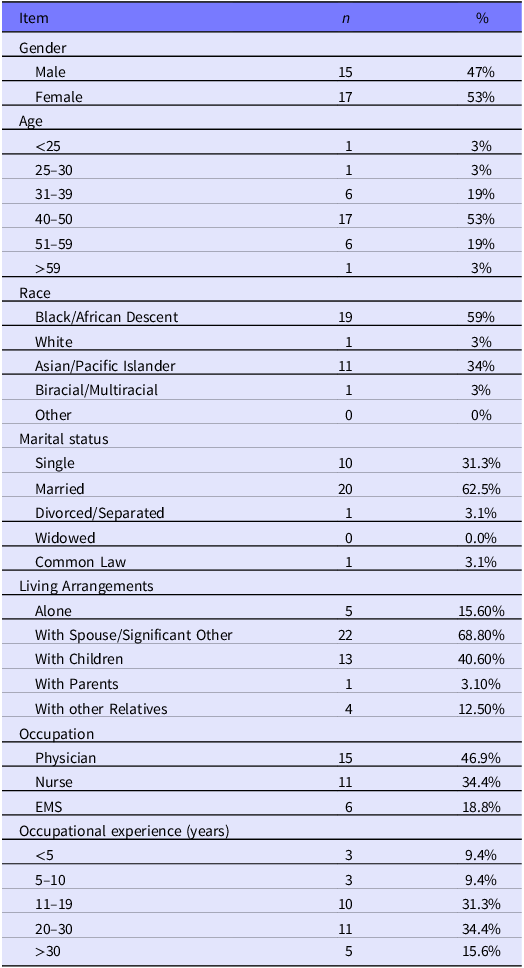

Fifty-seven (57) participants were emailed surveys and 33 responded (Response Rate = 57.9%). One (1) incomplete survey was excluded from data analysis (n = 32). Slightly more than 50% (53.1%, n = 17) of responders were female, between the ages of 40 to 50 years old (53.1%, n = 17), and of African/ Black descent (59.4%, n = 19). The study group was comprised of physicians (46.9%, n = 15), nurses (34.4%, n = 11), and EMS (18.8%, n = 6), with 34.4% (n = 11) having 20-30 years of work experience in their field (Table 1). Fifty-three percent (53.1%, n = 17) worked in the Accident and Emergency Department in the immediate aftermath of Dorian; 62.5% (n = 20) lost personal property and 9.4% (n = 3) lost a loved one during the storm. During the COVID-19 pandemic 53.1% (n = 17) became infected, 56.3% (n = 18) had to be quarantined due to close contact with a positive case, and 37.5% (n = 12) lost a loved one due to COVID-19. When asked about the types of psycho-social support utilized during this time, 90.6% (n = 29) of participants turned to family and friends. Paid leave was the second most used (18.8%, n = 6) method of psychological support.

Table 1. Participants Socio-demographics

Moral Distress Scores With Hurricane Dorian and Covid-19 Impact

Calculation of the participants’ MDS scores revealed that 15.6% (n = 5) had very mild Moral Distress, 40.6% (n = 13) had mild Moral Distress, another 40.6% (n = 13) had moderate Moral Distress, and 3.1% (n = 1) had severe Moral Distress (Table 2). Examination of MDS scores by profession showed that 60 % (n = 9) of physicians’ MDS scores were at least in the moderate range, 81.8% (n= 9) of nurses’ scores were at least in the mild range and 66.7% (n = 4) of EMS personnel were also in the mild range (Table 2). Seventy-five percent (75%, n = 6) of participants who worked in the A&E during the passage of Dorian had at least mild Moral Distress. More than 50% of those who worked immediately after the passage of the storm (58.8%, n = 10) had at least moderate Moral Distress and 50% (n = 3) of those that worked through both, had mild Moral Distress. In relation to COVID-19, 83.8% (n = 26/31) of participants who worked during the pandemic had mild or moderate Moral Distress.

Table 2. Mean Moral Distress scores associations with Occupation, Patient care challenges & working through Hurricane Dorian & the Covid-19 Pandemic

Seventy-two percent (71.9%, n = 23) of participants rated ethical challenges as at least “mildly distressing.” Fifty-three percent (53.1%, n = 17) of responders rated lack of resources as at least “moderately distressing.” Pressure from external forces was rated as at least “mildly distressing” by 81.2% (n = 26) of participants and staffing challenges were at least “moderately distressing” to 50% (n = 16) of participants (Table 2).

Further examination of patient care situations by profession showed 40% (n = 6) of physicians rated lack of resources “severely distressing,” while only 27% (n = 3) of nurses rated it as at least mildly distressing. Fifty percent (50%, n = 3) of EMS rated lack of resources as “mildly distressing.” Physicians (46.7%, n = 7) and EMS (66.7%, n = 4) rated ethical challenges as “mildly distressing,” while nurses were almost evenly split between ratings of “very mild” (36.4%, n = 4), “mild” (27.3%, n = 3), and “moderately distressing” (36.4%, n = 4). Fifty-three percent (53%, n = 8) of physicians and 36.6% (n = 4) of nurses found pressure from external forces “mildly distressing.” The 6 EMS participants found this patient care situation “very mildly” (33.3%, n = 2), “mildly” (33.3%, n = 2), and “moderately distressing” (33.3%, n = 2). Regarding staffing challenges, 63.6% (n = 7) of nurses gave a rating of “moderately distressing.” Staffing challenges were rated at mildly distressing by 46.7% (n = 7) of physicians and “very mildly” (33.3%, n = 2) and “mildly (33.3%, n = 2) distressing” by EMS (Table 2).

Those that worked during Hurricane Dorian found lack of resources “severely distressing” (37.5%, n = 3), and pressure from external sources (37.5%, n = 3), as well as staffing challenges (50%, n = 4) “moderately distressing.” Those that worked immediately after found all these situations “mildly distressing.” Fifty percent (50%, n = 3) of responders who worked at both times rated staffing challenges as “moderately distressing.” Staffing challenges were also rated at “moderately distressing” by 38.7% (n = 12) of those that worked during the pandemic. They also rated lack of resources as “mildly” (32.3%, n = 10) and “severely” (32.3%, n = 10) distressing (Table 2).

Moral Distress Score Associations

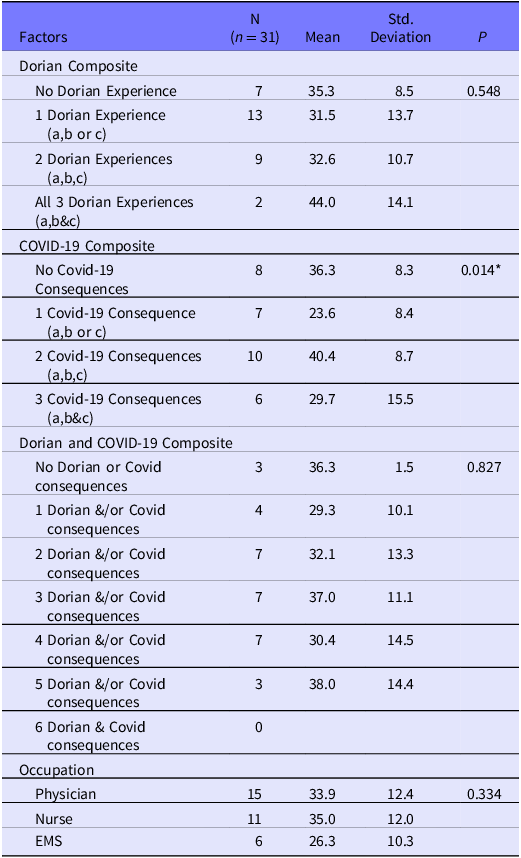

Participants with 2 negative experiences from COVID-19 were associated with statistically significant increases in MDS scores compared to participants with 1 negative experience from COVID-19 (40.4 vs. 23.6, P = 0.014) (Table 3). MDS scores tended to be higher but were not statistically significant for participants who were infected with the COVID-19 virus (34.8 vs. 30.7, P = 0.335), or quarantined due to contact with the COVID-19 virus (33.7 vs. 31.9, P = 0.679), but was lower for participants who lost loved ones due to the COVID-19 virus (28.3 vs. 35.7, P = 0.091).

Table 3. MDS scores across accumulated Hurricane Dorian & COVID-19 experiences

Dorian composite comprises: (a) worked during or both during and after Hurricane Dorian struck, (b) lost property due to Hurricane Dorian, (c) lost loved one due to Hurricane Dorian.

COVID composite comprises: (a) infected with COVID-19 virus, (b) quarantined due to contact with COVID-19 virus, (c) lost oved one due to COVID-19 virus.

There was only one participant who did not work during or after Hurricane Dorian. This participant was also the only participant who did not work during the COVID-19 pandemic. This participant was excluded from this analysis.

* Bonferroni post hoc group comparison showed statistically significant difference in means between participants who experienced 2 of 3 versus 1 of 3 COVID-19 situations, p = 0.014.

Participants who exercised > 6 times per week were found to have a statistically significant decrease in MDS score (12.50 SD 7.78, P = 0.02) (Table 4). Participants with psycho-social support from family and friends tended to have a lower mean MDS score of (32.5 vs. 36.7, P = 0.573), but did not reach statistical significance (Table 3). Responders who utilized: free communication of concerns with a supervisor (32 vs. 32.9, P = 0.917), a mental health professional (26 vs. 33.1, P = 0.568), Institution’s mental health and stress management seminars (30 vs. 33.1, P = 0.732), regularly scheduled facilitated focused employee discussion groups (26 vs. 33.1, P = 0.568), and department social events or team building exercises (30.5 vs. 33, P = 0.777) also tended towards non-statistically significant lower mean MDS scores. Those that utilized: peer support groups (40.7 vs. 32.1, P = 0.242), scheduled adjustments to allow for adequate rest (37.5 vs. 32.6, P = 0.581), and took paid leave (36.7 vs. 32.5, P = 0.573) tended to have non-statistical significantly higher mean MDS scores (Table 4).

Table 4. Mean Moral Distress Scores by Socio-demographics & Experiences

* Bonferroni post hoc group comparison did not show statistically significant difference comparing means.

^ Bonferroni post hoc group comparison showed statistically significant difference in means between participants who engaged in exercise >6 times per week compared to 2–3 times per week, p=0.046.

Factors related to individual experiences with Hurricane Dorian and COVID-19 were entered into the multiple regression models to examine independent associations with Moral Distress (Table 5). Losing a loved one due to Hurricane Dorian was found to have a non-statistically significant trend toward higher Moral Distress scores (B = 0.34 95% CI −1.23 to 28.75, P = 0.07). Losing a loved one due to COVID-19, however, was found to have a lower association with Moral Distress (B = − 0.42 95% CI −19.70 to − 0.88, P = 0.03).

Table 5. Multiple Regression for Moral Distress Scores

Factors related to individual experiences with Hurricane Dorian and COVID-19 were entered into the multiple regression to examine the individual association with Moral Distress. Assumptions of multiple linear regression analysis were met.

Discussion

Most of the participants had mild-moderate Moral Distress scores. Physicians had moderate MD, while nurses and EMS workers had mild MD. This finding differs from previous studies in which MD intensity was higher in nurses due to the belief that physicians had decision-making control over patients and less direct contact. Reference Epstein, Whitehead and Prompahakul13,Reference Whitehead, Herbertson and Hamric22 Physicians in the Bahamas have longer and more direct patient interactions than in some other systems, as they are required to perform most bedside procedures such as foley catheter insertion, intravenous cannula insertion, blood collection, and wound care, which are often performed by other staff like phlebotomists or Emergency Room technicians in many settings. Reference Epstein, Whitehead and Prompahakul13,Reference Whitehead, Herbertson and Hamric22,Reference Hamric and Blackhall23 Physicians’ scores may also be elevated due to their rating of lack of resources as “severely distressing,” a finding also seen in the 2019 Epstein et al. study.

Most of the participants that worked immediately after the passing of Hurricane Dorian had moderate MD. In contrast, those that worked during the storm or at both times had mild MD. A study of healthcare workers that worked during Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 found that persons who were inside the hospital experienced a protective “bubble” that isolated them from the external events of the storm, which led them to be able to block out negative thoughts. Reference Hugelius, Adolfsson and Örtenwall6 This phenomenon may have occurred with participants that worked in the hospital during Hurricane Dorian. Crisis situations require a heightened focus on the immediate tasks at hand and lead to increased teamwork among hospital staff. The shared goal of managing the disaster can create a supportive environment and provide a sense of protection within the team. Participants that were outside the hospital during the storm, but worked immediately after, were more exposed to the destruction, and had a higher potential to suffer alone, through personal traumatic events that may have been left unresolved prior to reporting to duty, such as property damage, and loss. This group also struggled with the consequences of the aftermath of the storm such as resource shortages, limited clinical space, increased patient load, and a prolonged recovery phase which may have made their MD worse.

Many who worked during the COVID-19 pandemic had mild-moderate MD. Participants may have developed a level of moral resilience over time as this study occurred 3 years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and healthcare workers had adapted during this time. Reference Kreh, Brancaleoni and Magalini24 Moral resilience is defined as the ability to sustain or restore one’s integrity in the face of moral challenges and has been shown to occur with support from employers and coworkers. Reference Spilg, Rushton and Phillips18,Reference Rushton25,Reference Rushton26 More than 50% of the responders thought the lack of resources and staffing challenges were moderately distressing. This finding is in line with a study on MD in Swedish healthcare workers that found lack of resources created great moral stress for staff. Reference Gustavsson, Juth and Schreeb16 In 2023, Gustavsson et al. included staff in lack of resources. This study separated staffing challenges and included limited staffing numbers and competency levels in this category. More than 50% of the nurses rated staffing challenges as moderately distressing; however, physicians found staffing challenges to be mildly distressing. In December 2022, it was reported that the public healthcare system in Grand Bahama lost 19 nurses in 2021 and 14 in 2022 through resignations. Reference Thompson-Evariste27 Prior to 2019, the rate of nursing loss from resignation was less than 10 per year, and prolonged working hours to cover staffing deficits were noted to be a cause. Reference Thompson-Evariste27 The aftermath of Dorian and the pandemic appears to be an impetus in the nursing resignation rate doubling 2 years later. There are over 200 nurses currently in the system on Grand Bahama to support a population of under 48 000. Reference Gibson28 In contrast, 2 physicians in the A&E resigned before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nearly 50% of the physicians found the lack of resources severely distressing, while nurses were even across severity levels of MD. In developing the measure of Moral Distress for healthcare professions in 2019, Epstein et al. found that “lack of resources” was rated as 1 of the top 5 causes of MD in physicians in their study. Reference Epstein, Whitehead and Prompahakul13 In the aftermath of Dorian, the A&E department at RMH was severely impacted with limited bed space due to the destruction of the rest of the hospital, and experienced extreme overcrowding that persisted, and worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic also introduced challenges of supplying PPE to hospital staff due to supply-chain shortages and shipping delays. This made evaluating and managing patients difficult for physicians, which may have led to their rating of lack of resources as “severely distressing” All professionals thought ethical challenges and pressure from external forces were mildly distressing. Gustavsson et al.’s 2023 study also noted that moral dilemmas were not the main cause of MD, but lack of resources was. Reference Gustavsson, Juth and Schreeb16 Most participants were between 40 – 50 years old with 20 – 30 years of work experience, and therefore had years of dealing with ethical challenges before the pandemic, which may have provided some level of moral resilience compared to previous studies. Reference Gustavsson, Juth and Arnberg15

Participants who suffered from multiple negative experiences from COVID-19 had higher MD scores. These people had experienced a combination of being infected with the virus, requiring quarantine due to contact with a positive case, and/ or losing a loved one. These were also considered stressors in previous Covid -19 studies. Reference Kreh, Brancaleoni and Magalini24,Reference Dai, Hu and Xiong29 The concern for their safety and that of their loved ones may have contributed to higher Moral Distress scores in the study group. Reference Kreh, Brancaleoni and Magalini24 However, the loss of a loved one due to COVID-19 alone was associated with lower scores. The type of death, prior end-of-life actions, and the relationship with the deceased have already been described as impacting the level of grief experienced. Reference Rabow, Huang and White-Hammond9 It is possible that the death of a loved one from COVID-19 may have strengthened the study group’s resolve to combat the pandemic, leading to lower MD scores. Previous studies of grief and psychological stressors in healthcare workers during the pandemic identified self-isolation from friends and relatives for fear of infecting them as a contributory factor. Reference Rabow, Huang and White-Hammond9,Reference Kreh, Brancaleoni and Magalini24,Reference Ansari30,Reference Eftekhar, Naserbakht and Bernstein31 In those studies, when death of a loved one occurred, they were unable to mourn properly and may have experienced what Rabow et al. described as “disenfranchised grief,” which occurs when one cannot openly acknowledge or publicly mourn their loss due to shame or guilt of causing the illness, or not being present when they died, and therefore, grieve alone. Reference Rabow, Huang and White-Hammond9 In our study, the participants had support from family and friends, and only quarantined when they had contact with a positive case, or isolated when tested positive. It is possible that this support was used after the death of a loved one and may have lessened the MD experience.

Conversely, those who lost a loved one during Hurricane Dorian had higher MD scores. It is well known that unexpected death is linked to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder. Reference Atwoli, Stein and King32 These deaths occurred suddenly, with no time to mentally prepare for the loss, thus increasing trauma to those left behind. Reference Hugelius, Adolfsson and Örtenwall6,Reference Gesi, Carmassi and Cerveri33,Reference Kristensen, Weisaeth and Bereavement34 This group includes those who’s loved one went missing and was not found dead, so they may also suffer from the stress and grief of “ambiguous loss,” which differs from confirmed death due to the lack of closure the loved one’s experience. Reference Boss and Yeats35 The survey asked about losing a loved one but did not specify only death. There are currently still over 200 persons missing after Hurricane Dorian, some of whom are likely relatives of healthcare workers.

Daily exercise decreases MD significantly and improves moral resilience when used as a part of self-care regimens. Reference Rabow, Huang and White-Hammond9,Reference Rushton, Christine Westphal and Campbell36 Family and friends were the most utilized means of support, aligning with previous studies. Reference Gustavsson, Arnberg and Juth8,Reference Gustavsson, Juth and Schreeb16 Support tools that required a level of self-reflection and discussion were associated with decreased scores of MD. Reference Gustavsson, Juth and Arnberg15 Those who took time off, however, had increased MD scores. These people may have needed time off due to their increased levels of distress. While time off may improve employee well-being by giving the individual time to regroup and recharge, MD may end up unchanged or worsen upon return if the patient care challenges which prompted the time off remained unchanged. Gustavsson et al., in 2023 noted that moral stress could not be improved unless the underlying factors were addressed, which require adequate peer support, and effective leadership. Reference Gustavsson, Juth and Schreeb16 Due to the differences in how individuals handle and process stressful situations, psycho-social interventions may also need to be tailored to individual needs to ensure beneficial outcomes. Reference Eftekhar, Naserbakht and Bernstein31

Limitations

This study had a small sample size of individuals at 1 institution with a response rate of 58%. As an exploratory study, this population was selected because of their experiences with emergency response to a catastrophic natural disaster and a pandemic within only a few months. Demographically, the study population was diverse; however, most of the physicians in the department responded to the survey, but a lower response rate among nursing and EMS staff may make the generalizability of results to other settings challenging as other studies had higher nursing representation. Reference Epstein, Whitehead and Prompahakul13,Reference Whitehead, Herbertson and Hamric22 There may be inherent biases present, being an observational study using an emailed questionnaire. Subjects may have felt uncomfortable reporting drinking and smoking practices truthfully, even though participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. There is also a possibility of self-selection bias, in that those most likely to suffer from moral distress were more likely to complete the survey, as seen in the higher number of physician responses. Those more likely to suffer from MD would also be the most likely to have left the healthcare system within the last 3 years and would not have been available to participate in the study. Conversely, some may have rated their distress intensity lower so as not to be found to have MD. The study was conducted 3 years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the time elapsed from the aftermath of Hurricane Dorian and the pandemic’s start may have impacted recall bias and allowed time for introspection, thus influencing moral distress intensity. Reference Hugelius, Adolfsson and Örtenwall6 However, with continued emergency department overcrowding and staffing shortages, responders were likely to still experience some level of MD.

Conclusion

The Emergency medical staff at the RMH who participated in this research reported having mild-moderate MD. This is one of the first studies to look at the impact of consecutive disasters on MD in emergency medical providers in the Bahamas and gives insight into stressors that affect staff well-being. Experiences with Hurricane Dorian and the following COVID-19 pandemic were shown to have a significant impact on MD. These experiences also influenced the intensity of MD that people perceived around issues that affected patient care, such as lack of resources, staffing challenges, and pressure from external forces. Family and friends were the primary support for responders, and psycho-social support services that allowed for communication and introspection reduced MD in this group. Healthcare administrators should consider the following recommendations to lessen the burden of MD in future disaster response:

-

1) Leadership should provide clear and timely communication regarding the disaster to limit misinformation and reduce anxiety from uncertainty.

-

2) Provide regularly scheduled debriefing sessions that encourage medical professionals to openly express their concerns and frustrations.

-

3) Provide a stigma free environment to encourage providers to seek Mental Health support.

-

4) Foster a community of teamwork to ensure collaboration and mutual respect amongst all levels of staff, ensuring support during crises.

-

5) Involve medical providers in the development of clear guidelines for resource allocation during crises to ensure a sense of fairness and consideration.

-

6) Regularly review, update and train on the institution’s emergency policies to ensure staff know their roles and how to respond, thereby decreasing staff anxiety and frustration.

This study adds to the literature on moral distress in Emergency physicians. Future studies are needed to determine the psycho-social services that best support this population to improve moral resilience, long-term mental health outcomes among emergency medical staff from consecutive disasters, as well as healthcare system factors such as resource allocation, and staffing policies, plus communication strategies to determine areas where support for their emergency medical providers can be improved for future disaster responses.

Authors’ contribution

Latoya E. Storr: Investigator and lead author; Attila J. Hertelendy: Research advisor and editor; Alexander Hart: Research advisor and editor; Lenard Cheng: Statistical analysis; Fadi Issa: Advisor and editor; Todd Benham: Subject matter advisor; Gregory Ciottone: Principal investigator.

Competing interests

None.