Introduction

Leading authorities in psychiatry, and medicine more generally, now agree that available evidence justifies the inclusion of a grief disorder in the DSM and ICD. Despite agreement that prolonged, intense, disabling grief constitutes a mental disorder, there is a lack of agreement on the name of the disorder and on the criteria that clinicians should use to assess it. The new disorder, and comprehensive evidence in support of it, were originally introduced in a proposal for prolonged grief disorder (PGD). Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Asian and Goodkin1 Following this proposal for PGD and its presentation to the DSM-5 subwork group, an alternative proposal for complicated grief appeared in a review article. Reference Shear, Simon, Wall, Zisook, Neimeyer and Duanet2 The proposal for complicated grief was absent of any evidence that it accurately diagnosed the underlying grief disorder. Resolution of the conflict between these two proposals will remove any obstacles to consensus on criteria that has impeded progress in diagnosis and treatment of the many individuals who suffer from pathological grief. Here we provide a rationale and evidence in support of PGD, as opposed to complicated grief, as the criterion standard for disordered grief.

Background

In 1999, we published a preliminary report in the BJPsych Reference Prigerson, Shear, Jacobs, Reynolds, Maciejewski and Davidson3 that tested consensus criteria for disordered grief. A National Institutes for Health/National Institute of Mental Health-funded field trial, the Yale Bereavement Study (YBS), then followed to refine and test those criteria. That study produced a proposal and diagnostic criteria for PGD, Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Asian and Goodkin1 defined as a genuine disorder of grief, characterised by intense, unrelenting grief-specific symptoms of loss such as yearning and physical or emotional suffering caused by the wanted, but unfulfilled, reunion with the deceased. This empirical study, published in 2009, Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Asian and Goodkin1 demonstrated that PGD met well-established criteria required for the validation of a new mental disorder. Reference Feighner, Robins, Guze, Woodruff, Winokur and Munoz4

Following the 2009 publication, which demonstrated the validity of the PGD proposal, Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Asian and Goodkin1 we made our case for PGD as a new diagnostic category directly to members of the DSM and ICD work groups. Both took the proposal for PGD seriously and have taken steps to introduce it into their diagnostic classification systems. The DSM expanded criteria for PGD to include unexamined elements of complicated grief, and renamed the disorder persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD). The ICD simplified the validated PGD criteria by reducing the number of symptoms to be considered for a diagnosis but retained its name, PGD. A recent analysis comparing these criteria demonstrated that PGD criteria, the DSM's more elaborate PCBD criteria and the ICD's simpler PGD criteria, but not complicated grief criteria, are all substantively the same and have strong diagnostic properties. Reference Maciejewski, Maercker, Boelen and Prigerson5

Evaluation of the evidence regarding complicated grief as a mental disorder

To date, there is no evidence that complicated grief criteria, despite its obvious overlap and similarities with PGD, accurately identify individuals with a distinct mental disorder. Recently, we found that complicated grief had moderate agreement with PGD and PCBD. We identified 30% of our YBS community sample as having complicated grief as opposed to 10–15% for PGD and/or PCBD, that it produced more false positives (63%) than true positives (37%) with respect to our criterion standard, and, unlike PGD and PCBD, complicated grief had no predictive validity with respect to future mental disorder, functional impairment or diminished quality of life. Reference Maciejewski, Maercker, Boelen and Prigerson5 Thus, complicated grief proved to be the unsubstantiated proposal in that it, unlike the other formulations, it did not meet accepted criteria Reference Feighner, Robins, Guze, Woodruff, Winokur and Munoz4 for defining a mental disorder.

The assertion that complicated grief is not a mental disorder is at odds with the main conclusion of another recent report. Cozza et al Reference Cozza, Fisher, Maura, Zhou, Ortiz and Skritskaya6 compared PCBD, PGD and complicated grief criteria and concluded that the complicated grief criteria are superior to those for PCBD and PGD. We disagree with this conclusion, and given rates of overdiagnosis and flaws with the study design employed by Cozza et al, we draw the opposite conclusion. Concerns with the Cozza et al methodology and conclusions are detailed below.

The complicated grief criteria are, in our opinion, too easily satisfied. Not only is the number of symptoms to meet the complicated grief criteria too few – just one ‘category B’ and two ‘category C’ symptoms – but also the threshold required in Cozza et al for each symptom is too low – only ‘moderate’ (severity ⩾ 3 on a five-point Likert scale). This would mean, for example, that a bereaved individual with moderate yearning for the deceased and two additional symptoms such as moderate ‘reluctance to pursue interests since the loss …’ and moderate ‘difficulty with positive reminiscing about the deceased’ would meet complicated grief criteria for pathological grief. As mentioned above, in a recent World Psychiatry report, Reference Maciejewski, Maercker, Boelen and Prigerson5 we found that the positive complicated grief test rate in our YBS community sample was 30% when we apply our standard symptom threshold of ‘quite a bit’ (severity ⩾ 4 on a five-point Likert scale) for each symptom. If we use Cozza et al's ‘moderate’ symptom threshold, then the positive complicated grief test rate in our YBS sample is 62%. Reference Prigerson and Maciejewski7 A diagnostic test that identifies a majority of individuals in an ordinary, community-based, bereaved sample as having pathological grief contradicts the notion that most grief reactions are normal.

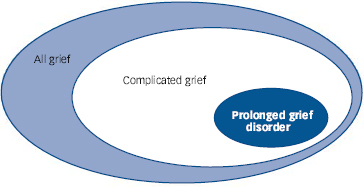

Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between all grief, complicated grief and PGD in the YBS sample based on Cozza et at's ‘moderate’ symptom threshold for diagnosis of complicated grief and our conventional ‘quite a bit’ symptom threshold for PGD. Bereavement is a common, ubiquitous life event. Institutionalisation of complicated grief criteria in the DSM would translate into many normal bereavement reactions being diagnosed as a form of mental illness. From a public health perspective, criteria that diagnose most reactions to a natural life event as a psychiatric disorder lack credibility.

Fig. 1 Relationships between all grief, complicated grief and prolonged grief disorder in the Yale Bereavement Study (YBS) sample.

All grief, 100% of all bereaved individuals in the YBS sample; complicated grief identified using Cozza et al symptom threshold, 62% of all bereaved individuals in the YBS sample; prolonged grief disorder using Prigerson et al symptom threshold, 12% of all bereaved individuals in the YBS sample.

The fatal flaw of Cozza et al's study disqualifying it from serious consideration can be summarised in two words: ‘spectrum bias’. Cozza et al removed nearly half (n = 797, 46%) of their total sample from their main analysis to focus only on extreme ‘cases’ (n = 260, 15% of total sample) and ‘controls’ (n = 675, 39% of total sample). Long ago, Ransohoff & Feinstein Reference Ransohoff and Feinstein8 described the problem of ‘spectrum bias’ associated with study designs that exclude the most difficult cases to diagnose in favour of the most obvious cases and controls. Diagnosticians have cautioned against such case–control designs Reference Lijmer, Mol, Heisterkamp, Bonsel, Prins and van der Meulen9 ever since because they overestimate the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic tests by omitting diagnostic errors from near-threshold cases. The value of a diagnostic formulation's ability to discriminate between cases and controls is not in identifying extremes, but rather in discerning the cases that lie in between these extreme groups of obviously normal and obviously pathological cases. Undoubtedly, Cozza et al's spectrum-biased design conceals many false-positive diagnostic tests for complicated grief in the large segment (46%) of their sample excluded from their main analysis. This critical information was neither reported in Cozza et al's study, nor provided to us by the authors after requests for these numbers (personal communication).

Beyond our fundamental concerns about the ease with which complicated grief criteria may be satisfied and Cozza et al's logic, design and analysis, there are some striking commonalities between their study and ours. Data from Cozza et al Reference Cozza, Fisher, Maura, Zhou, Ortiz and Skritskaya6 and our YBS Reference Maciejewski, Maercker, Boelen and Prigerson5 are consistent with three basic facts. First, PGD and PCBD, and not complicated grief, represent the same diagnostic entity. Second, the rate of diagnosis of complicated grief is two to three times greater than that of PGD and/or PCBD. Third, individuals who meet criteria for PGD (and/or PCBD) are a subset of those who meet criteria for complicated grief. This means that complicated grief (using a symptom severity threshold of ⩾4 on a five-point Likert scale) is composed of a substantial minority of individuals (~40%) who have PGD, i.e. a genuine disorder of grief, and a majority of individuals (~60%) who do not. This 60% is a group we consider misclassified (i.e. wrongly pathologised) by the complicated grief criteria.

Thus, evidence from two independent, federally funded community-based bereavement studies, including Cozza et al's own data, lead us to reject Cozza et al's assertion of complicated grief criteria's superiority. Cozza et al conclude that the DSM should modify its PCBD criteria to be more in line with theirs. However, this would mean basing DSM criteria on complicated grief criteria that have not been empirically validated, that overdiagnose/pathologise normal grief and that produce more false than true positives. In fact, the evidence converges in support of unifying behind PGD as the diagnostic standard for disordered grief.

Conclusions

The purpose of diagnostic criteria is to provide a uniform and agreed upon (i.e. standardised) method for determining which individuals are truly suffering from a legitimate disorder. Valid and reliable diagnoses are a prerequisite for determining appropriate treatment; they should not, however, be used as a device for identifying whom to treat. PGD, and the DSM and ICD versions of it, accurately and reliably diagnose bereaved individuals who experience significant psychological distress and dysfunction, avoid pathologising normal bereavement reactions and identify individuals for whom severe and debilitating grief is likely to endure without effective intervention. We believe that PGD criteria achieve these goals and would be an empirically supported and clinically useful addition to the DSM and ICD.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.