The Lincoln Lunatic Asylum, opened in 1820, was England's first purpose-built hospital for the treatment of the mentally ill. In 1885 it was renamed the Lawn Hospital for the Insane. It was famous for preventing physical restraint and isolation while providing a sympathetic environment for its patients.

Dr Mary Barkas was the medical superintendent at The Lawn from 1927 to 1932. At a time when women were largely dismissed in English psychiatry, Barkas, originally from New Zealand, had a career of some distinction. She had won the Gaskell Medal, was the first woman to work at the Bethlem Hospital, trained as a psychoanalyst with Otto Rank and was one of the medical officers appointed when the Maudsley Hospital opened in 1924, working closely with William Dawson.

Her career blighted by the recurrent problem of women not being able to get permanent positions in London County Council (LCC) hospitals, Barkas resigned from the Maudsley in frustration and took the position at The Lawn in 1928. Such private hospitals, depending on charity, donations and bequests, existed in an uneasy limbo until the National Health Service was established. The situation at The Lawn can be traced by its annual reports. In 1928, there were 60 patients under care, 13 of 29 admissions were voluntary boarders, with 12 in residence on December 31. There were six deaths, including two from the influenza epidemic. In 1930, there were 43 admissions, the average resident number was 65 and, for the first time, voluntary patients exceeded those who were legally detained. The financial situation, now a ‘serious problem’, could not be ignored: it was difficult to provide a service at less than £4.4 s per patient per week and the governors appealed for more funds.

Her enthusiasm notwithstanding, Barkas found it a struggle to increase patient numbers. By 1931, admissions included 22 voluntary boarders and 10 certified patients. The recovery rate was 66.6% and there were five deaths from natural causes. Work was hampered by lack of funds and a special appeal was made to supplement them. However, 38 enquiries did not lead to admission because the charitable resources were insufficient. The following year, the hospital was only half occupied and the governors faced ruin. Barkas offered to reduce her salary, but the governors refused to accept this.

Barkas became dejected by the problems. A bad loss occurred when a patient threw herself from a second-storey window. In 1932, when her father Fred became ill, she returned to New Zealand. The following year, Fred having died, she advised the governors of her resignation and remained in New Zealand. Disillusioned and depressed, Barkas was never to practise psychiatry again. She died in 1959, her obituary in the BMJ written by William Dawson.

The story of private psychiatric hospitals that struggled during the Depression, hanging on until the establishment of the NHS, is mostly unwritten. Mary Barkas is also a largely forgotten figure who deserves wider recognition.

Robert M. Kaplan's book Mary Barkas: A Life Unfulfilled is currently in press.

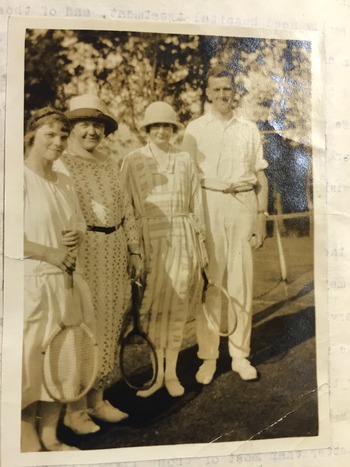

Fig: The Maudsley Tennis Team: Mary Barkas is second from the left, William Dawson on the right (Copyright © Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.