Alexandra Pitman (pictured) is an MRC Research Fellow in the Department of Mental Health Sciences, University College London, where she is investigating the impact of suicide bereavement. David Osborn, is a Senior Lecturer in community psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology in the Department of Mental Health Sciences, University College London, and is an honorary consultant psychiatrist.

Analysis of World Mental Health Survey data by Bruffaerts et al in this issue describes healthcare use by individuals who are suicidal in 21 countries. Reference Bruffaerts, Demyttenaere, Hwang, Chiu, Sampson and Kessler1 Only 39% of the respondents who were suicidal had sought treatment of any type in the previous year. This low rate ranged from 17% in low-income countries to 56% in high-income countries, and is alarming given the association between self-harm and completed suicide. Reference Owens, Horrocks and House2 Yet the leading reason for not seeking help was not stigma or structural/financial constraints, but low perceived need, with 58% of those respondents endorsing the statement ‘The problem went away by itself, and I did not really need help’. Reference Bruffaerts, Demyttenaere, Hwang, Chiu, Sampson and Kessler1 The second most common barrier (ranked first in high-income countries) was respondents’ attitudes, identified as the low perceived efficacy of treatments, the desire to handle the problem alone and (in only 7%) stigma. Structural barriers, for example lack of access to treatment, ranked third overall.

These findings develop our understanding of help-seeking in suicidal crises, challenging the conventional wisdom that stigma and structural/financial constraints are the major barriers to accessing mental healthcare. Although the household residents sampled probably underrepresent those with more intense suicidality, the majority who had felt suicidal did not believe that services offered tangible benefits. If such attitudes constitute a genuine obstacle to the delivery of suicide prevention interventions, each nation must rethink its suicide strategy. Rather than pushing evidence-based interventions blindly, we must determine what individuals who are suicidal would find helpful and actually seek out.

Perceptions of the need for care among people who are suicidal

Bruffaerts et al warn that low perceived need for care, as well as attitudinal barriers, cause delays in treatment and the risk of clinical deterioration. However, delays in accessing healthcare increase the risk of progressive suicidality only if effective treatments are available. We should challenge three key assumptions in suicide prevention: that demand is the same as clinically determined need; that healthcare services provide the most appropriate setting for managing medically determined need; Reference Abel-Smith and Abel-Smith3 and that available interventions are effective for all clinical subgroups. There are many possible reasons for low perceived need, including an individual’s strong sense of self-efficacy and a containing social network. Indeed, self-care and informal care manage a key proportion of healthcare need in all societies. Yet given the high personal, societal and political cost of completed suicide, policy-makers and practitioners are certain to feel uneasy about the extent of care being provided outside mainstream auditable services.

Low perceived need is alarming when it arises from previous contact with uncaring practitioners, experiences of ineffective interventions or perceptions of services being ineffective. Systematic reviews indicate that people who self-harm report negative experiences when using clinical services, including stigmatising attitudes. Reference Taylor, Hawton, Fortune and Kapur4 Evaluations of interventions to reduce the repetition of self-harm have developed minimally a decade on from the initial Cochrane review. Reference Hawton, Townsend, Arensman, Gunnell, Hazell and House5 Generalisability of interventions is questionable, with most studies confined to secondary care, specific clinical subgroups Reference Pitman6 and high-income countries. Reference Patel, Araya, Chatterjee, Chisholm, Cohen and de Silva7 Looking beyond the dominance of Western healthcare models many of these interventions would be impossible to implement on any large scale in low- and middle-income countries, Reference Diekstra8 and consequently are not supplied.

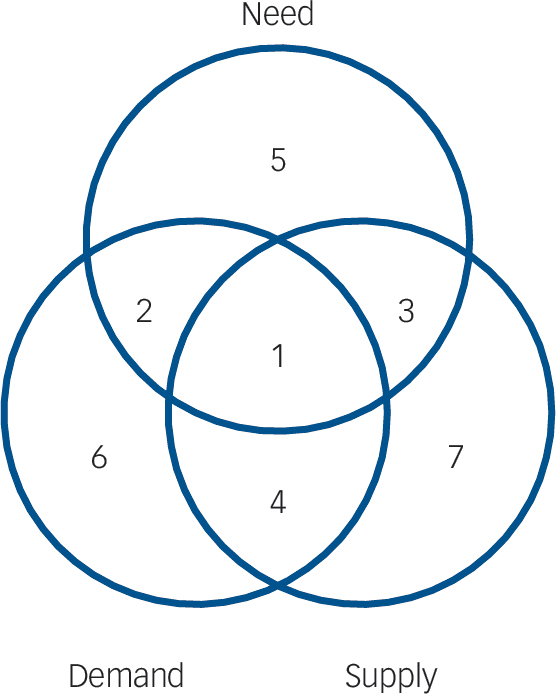

Bruffaerts et al Reference Bruffaerts, Demyttenaere, Hwang, Chiu, Sampson and Kessler1 feel they have identified a high level of unmet need (with negative connotations ascribed to attitudinal barriers), however the relationship between need, supply and demand represented inFig. 1 suggests an alternative interpretation: a low level of demand for formal healthcare (with positive connotations of self-efficacy). Patient satisfaction exerts a powerful force where consumers use their right to exit the mainstream healthcare market in favour of competing services, Reference Klein10 and is increasingly evaluated as part of service planning. What we learn about patient choice in this survey is that self-help, primary care and alternative practitioners are key competitors to secondary care, the very setting in which the evidence base is most developed. This is particularly marked in low- and middle-income countries where, for reasons of cost, cultural appropriateness, and feasibility, evaluations of informal care and alternative practitioners have yet to be conducted. Given that absence of evidence is not evidence for ineffectiveness, and that many consumers express a

Fig. 1 Venn diagram showing how need, demand and supply overlap in relation to suicide prevention interventions. Adapted from Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Raftery, Mant, Stevens, Raftery and Mant9

Examples of interventions in each numbered area: (1) provision of evidence-based and culturally acceptable interventions to reduce suicide risk; (2) service gaps for provision of evidence-based and culturally acceptable interventions to reduce suicide risk; (3) suicide means-restriction policies; media blackouts on reporting suicides; (4) psychosocial interventions that increase risk by reinforcing self-harming behaviour; (5) evidence-based but culturally unacceptable interventions for individuals who are suicidal; evidence-based interventions for people who are suicidal who prefer to handle the problem alone; (6) internet-acquired benzodiazepines to palliate suicidal distress; (7) non-utilisation of ineffective psychosocial interventions.

preference for managing suicidal crises outside healthcare settings, we need to understand the nature of help that people who are suicidal value. If mainstream services for people with suicidal behaviour are not attractive to their target market, resources may need to be shifted into other settings.

Suicide prevention is a public health priority for the World Health Organization, which recommends improving access to health and social services. For most disease areas health policies will fail if the target populations do not utilise designated services. However, there are three reasons why suicide requires a different approach to other public health problems. First, as the responses to this survey suggest, notions of clinical need may differ in the case of suicidality. Second, suicidality is not a distinct diagnosis but a behaviour with diverse underlying aetiologies, and one blanket intervention is unlikely to be effective for all. Reference Pitman6 This lies in contrast to strong evidence of effectiveness in treating specific mental health diagnoses. Reference Patel, Araya, Chatterjee, Chisholm, Cohen and de Silva7 Third, the evidence base for suicide prevention programmes remains poor, apart from restricting access to lethal methods and training primary care physicians to evaluate suicide risk. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas11 Policy-makers must decide whether to use marketing principles (and scarce resources) to attract people who are suicidal into existing services, or invest in culturally appropriate interventions in more acceptable settings. Bruffaerts et al’s findings suggest the latter may be a more promising way of meeting suicide prevention targets, especially in a global context.

Taking a country-by-country approach

Cross-cultural variations in suicidal behaviour are not well-understood, particularly given the underresourcing of suicide research in low- and middle-income countries. Reference Jacob, Sharan, Mirza, Garrido-Cumbrera, Seedat and Mari12 As Bruffaerts et al discuss, cultural factors are involved throughout the help-seeking pathway. Reference Bruffaerts, Demyttenaere, Hwang, Chiu, Sampson and Kessler1 The studies they cite describe the impact of stigma and cultural distrust on service utilisation for individuals who are suicidal within different ethnic groups, suggesting there might be some overlap in the barriers to treatment their survey defines. The majority of this literature relates to Black and minority ethnic groups in higher-income countries, with questionable applicability to communities in low- and middle-income countries. Nevertheless, their data clearly show that stigma associated with suicidal behaviour is a disincentive to seeking care in all countries surveyed, adding to the evidence for stigma associated with mental disorders. Reference Angermeyer and Dietrich13 The myriad cultural differences within and between nations suggest that instead of a global ‘one size fits all’ solution to suicidal behaviour, a very different policy approach would need to be taken within each country.

The first step is to expand the quantitative and qualitative evidence base on the views of consumers, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. This would determine cultural influences on help-seeking preferences, and the value consumers place on primary care, traditional healers and the informal sector. Bruffaerts et al highlight primary care and non-mental healthcare providers as key entry points for suicidal people, but they are also care delivery points. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas11 The current Western focus on secondary care interventions Reference Hawton, Townsend, Arensman, Gunnell, Hazell and House5 should shift towards gatekeeper training programmes for primary care practitioners, religious leaders and traditional healers. Reference Goldston, Molock, Whitbeck, Murakami, Zayas and Nagayama Hall14 Consumer surveys would yield suggestions for acceptable care that could then be evaluated. Settings might include schools for provision of psychoeducation, primary care or community centres for delivering a range of psychotherapeutic approaches, and the home for use of manualised self-help packages.

Using cost-effectiveness data on a specified range of acceptable interventions, each country should then identify its national strategy. This set of interventions would cater for each key subculture and clinical subgroup, and include services outside mainstream healthcare. Substantial resource and feasibility implications are obviously involved in establishing individualised national suicide policy based on evidence of acceptability and effectiveness. This may require the use of innovative research designs, wider outcome measures, Reference Pitman6,Reference Goldston, Molock, Whitbeck, Murakami, Zayas and Nagayama Hall14 and international research collaborations.

Conclusion

Bruffaerts et al’s international survey of people who are suicidal suggests that policy-makers need to address an apparent rejection of mainstream services. Yet without knowing which interventions actually work, or how cultural values and differences influence acceptability in different settings, adhering to traditional specialist mental health models may prove unsuccessful. Cultural competence is as important at the macro-level (research design and policy-making) as at the micro-level (individual patient–practitioner interactions). Future research should deliver an international evidence base on the preferences of individuals who are suicidal, and evaluate tailored interventions for each clinical subgroup in a range of settings. Policy-makers will then have a more realistic chance of matching supply to need and demand in the marketing of suicide prevention services.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.