Breast-feeding practices have improved in the last decades in most of Latin America( Reference Lutter 1 – Reference Lutter, Chaparro and Grummer-Strawn 3 ). Exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) under 6 months of age has increased greatly in Brazil, Colombia and Peru. However in other countries, such as Mexico and the Dominican Republic, prevalence of EBF under 6 months of age has decreased( Reference Lutter, Chaparro and Grummer-Strawn 3 , Reference Gutierrez, Rivera-Dommarco and Shamah-Levy 4 ). Despite improvements, only in five of nineteen Latin American countries with nationally representative data on trends in EBF over a 10–20 year period do >50 % of mothers exclusively breast-fed babies under 6 months of age( Reference Lutter 1 ). Table 1 depicts rates of EBF under 6 months from Latin America including Tijuana.

Table 1 Rate of exclusive breast-feeding under 6 months in some regions of Latin America

In the last decades, changes in breast-feeding prevalence in Latin America have shown less improvement in population subgroups whose children are most at risk for mortality and increased morbidity from not being breast-fed, such as poorly educated women with little access to health care( Reference Chaparro and Lutter 5 , Reference Lutter, Chaparro and Grummer-Strawn 6 ). In Mexico, EBF under 6 months deteriorated among the poor (33·5 % to 16·6 %), rural (32·7 % to 18·5 %) and indigenous (46 % to 27·5 %) populations from 1999 to 2012( Reference González de Cossío, Escobar-Zaragoza and González-Castell 7 , Reference González de Cosío, Escobar-Zaragoza and González-Castell 8 ).

Breast-feeding rates in Mexico are one of the lowest of Latin America with 14·4 % of EBF under 6 months of age( Reference Lutter 1 ). Particularly in North Mexico, there is a lower prevalence of EBF under 6 months of age (10·6 %) than the national average in 2012( Reference Gutierrez, Rivera-Dommarco and Shamah-Levy 4 , Reference Olaiz-Fernández, Rivera-Dommarco and Shamah-Levy 9 ). There are no data with EBF rates in Tijuana from national surveys, but studies conducted locally have found lower breast-feeding rates than in the rest of the country( Reference Leyva-Pacheco, Bacardi-Gascon and Jimenez-Cruz 10 ). In a study( Reference Leyva-Pacheco, Bacardi-Gascon and Jimenez-Cruz 10 ) carried out at public hospitals, no woman reported exclusively breast-feeding her 3- or 6-month-old baby at the time of interview. Only 2·2 % of all women (with 3-, 6- and 12-month-old babies) indicated having exclusively breast-fed their babies for 90 to 180 d. Further, 82 % of mothers stopped breast-feeding altogether before their babies reached 4 months of age.

Breast-feeding rates reflect sociodemographic discrepancies. In the analysis of inequalities in breast-feeding, Cattaneo( Reference Cattaneo 11 ) identified three phases of breast-feeding prevalence: (i) an initial one with high prevalence and duration of breast-feeding across all population groups (stage 1); (ii) a transformation phase with prevalence and duration falling first among the urban elite, then among the urban and rural poor (stages 2–5); and (iii) a third phase of resurgence, in a sort of inverse pattern (stages 6–8). According to this scheme, Mexico would be between stages 4 and 6 because Mexico( Reference González de Cossío, Escobar-Zaragoza and González-Castell 7 – Reference Olaiz-Fernández, Rivera-Dommarco and Shamah-Levy 9 ) traditionally had significantly higher breast-feeding rates in rural (EBF under 6 months of age 32·7 % v. 14·8 % urban), indigenous (46·0 % v. 17·5 % non-indigenous) and low socio-economic (33·5 % v. 14·7 % high socio-economic) populations (1999) but that has been changing and breast-feeding has decreased to 18·5 % in rural areas, 27·5 % in indigenous and 16·6 % in low-income populations (2012). Mexico seems to be in the latter stages of the transformation phase where breast-feeding rates are decreasing among the rural poor and the third phase (resurgence) is emerging with the ‘sort of inverse pattern’ when breast-feeding rates increase first among the urban elite because there has been an increase in women with higher v. lower education (21·8 % v. 12·8 % in 2012).

In developing countries breast-feeding is higher in families with lower income, whereas it is lower in wealthier ones( Reference Gwatkin, Rutstein and Johnson 12 ). In industrialized countries, the opposite is usually observed( Reference Ryan, Rush and Krieger 13 ). One reason for this demographic pattern of breast-feeding in industrialized settings, according to Smith( Reference Hall Smith 14 ), is that ‘women who are able to function effectively within the existing structures do better, and women who have more control over their body, time, and space are able to breast-feed longer with better quality than women who have less control’.

Some of the problems to establish breast-feeding are related to our modern world, such as more people living in urban areas, inequalities in access to public services, health-care services that separate the infant–mother dyad at birth, the dual role of mothers as domestic/caregivers at home and workers, the lack of mother-friendly work environments and a marketing climate that demands the consumption of products to achieve social status( Reference Hausman, Hall Smith and Labbok 15 ).

The purpose of the present study was to identify the main societal obstacles to breast-feeding in the low-income population in Tijuana in order to develop specific, culturally appropriate educational material for breast-feeding promotion. We selected the socio-ecological framework adapted for breast-feeding by Hector et al.( Reference Hector, King and Webb 16 ) and Tiedje et al.( Reference Tiedje, Schiffman and Omar 17 ). This model shows an integrated view of breast-feeding practices and identifies factors that may be modifiable for intervention planning. These actions target modification of both individual behaviours and environments in which individuals live and breast-feed.

Methods

Study site

The border region of Tijuana/San Diego has been described as one of the busiest worldwide. The estimated total population of the region was just over 5 million in 2010, making it the largest bi-national conurbation shared between the USA and Mexico( Reference Rangel and Hernández 18 , Reference Anderson 19 ). Tijuana is well known in the rest of the country as a place where you can always find a job and have better living conditions. The target communities in the present study were located at the outskirts of the city (East Tijuana). They were selected based on the following conditions: being low-income with low accessibility to health-care centres and no existing breast-feeding promotion programmes. The marginalization of these disadvantaged communities creates frustration and discontent due to inability to access basic services and benefits that the city has to offer.

In Tijuana, there are numerous maquiladoras (assembly factories) that employ primarily female, semi-skilled, low-wage workers, to manufacture goods for the US market. Population growth on the border has led to quality-of-life improvements such as paved streets and access to education. However, this population growth is also a burden on the health-care system, which has resulted in limited health-care access. Additionally, the population of this region is characterized by high rates of migration from low-income areas from the south with a history of undernutrition which now encounter more availability of energy-dense food, creating a population at high risk to develop obesity( Reference Rangel and Hernández 18 – Reference Perez-Escamilla, Obbagy and Altman 21 ).

Design

In designing and implementing formative research, it is useful to apply a conceptual framework to help describe contextual influences on behaviour and assess optimal intervention entry points( Reference Clark and McLeroy 22 ). Based on the work of Bronfenbrenner( Reference Bronfenbrenner 23 ) and other system models, social ecology places the behaviour of individuals within a broad social context. Behaviour is viewed not just as the result of knowledge, values and attitudes of individuals but as the result of a host of social influences, including the people with whom we associate, the organizations to which we belong and the communities in which we live( Reference McLeroy, Norton and Kegler 24 ).

For the present study we used a socio-ecological framework adapted for breast-feeding( Reference Hector, King and Webb 16 , Reference Tiedje, Schiffman and Omar 17 ) that includes three levels: (i) individual-level factors are those associated directly with the mother, infant and the mother–infant dyad; (ii) group-level factors are the attributes of the environments that enable or disable mothers to breast-feed, such as the hospital and health facilities and the home and work environments; and (iii) societal-level factors influence the acceptability and expectations about breast-feeding and provide the context in which mothers’ feeding practices occur.

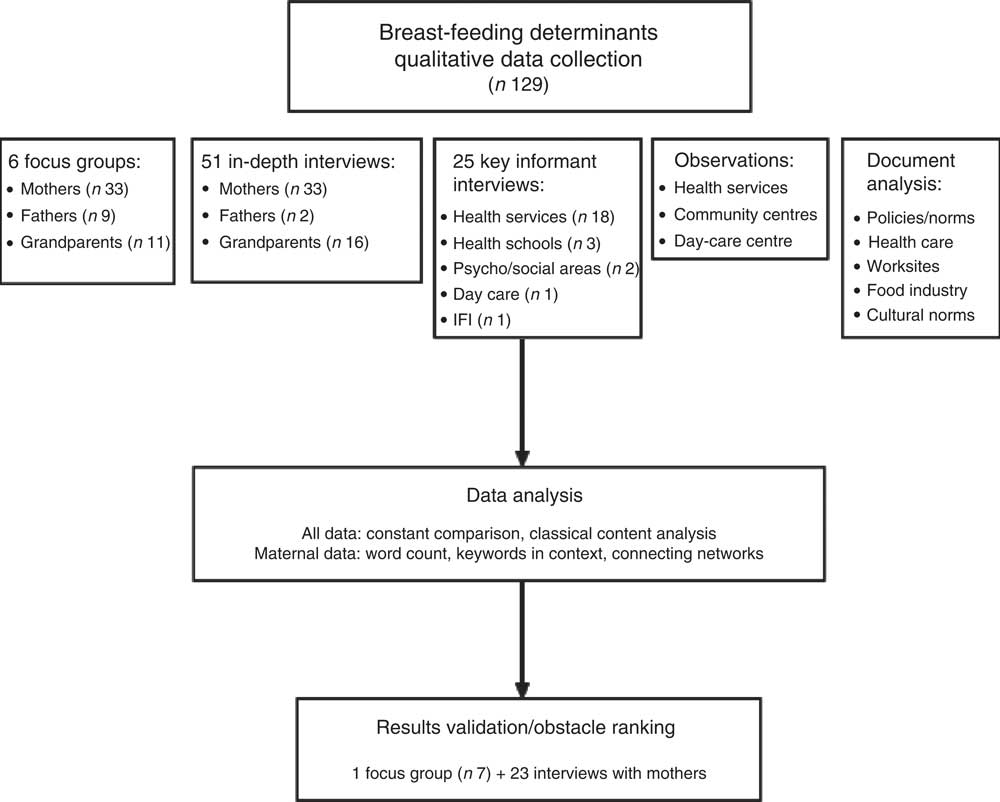

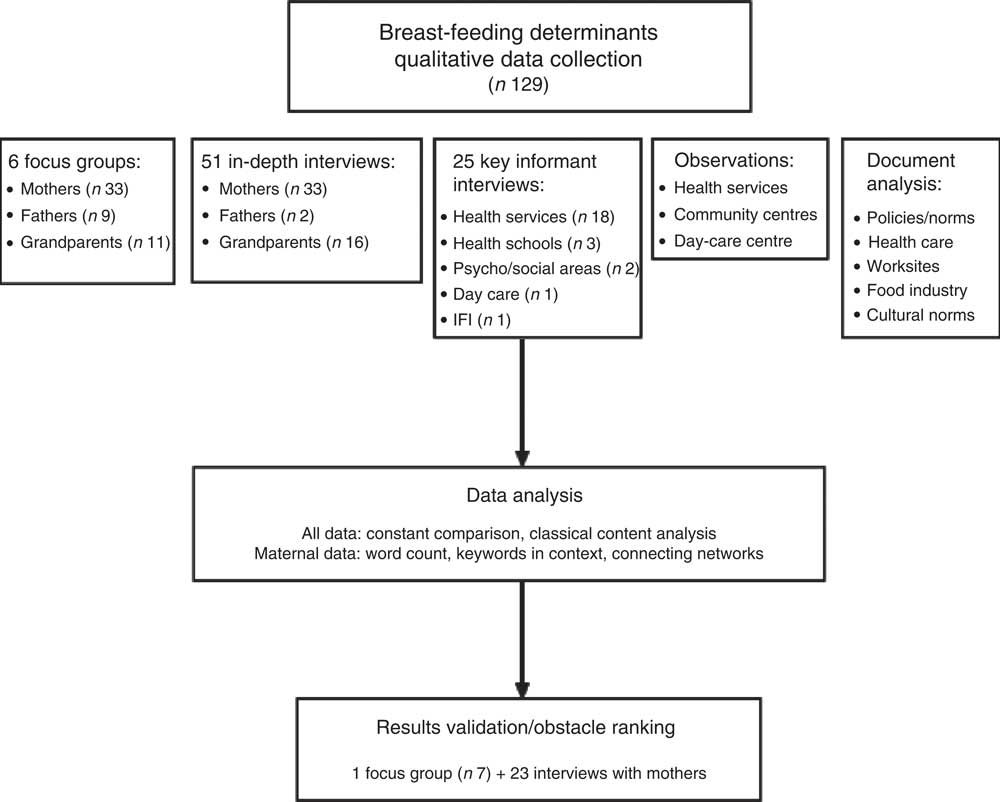

We used a variety of qualitative methods to assess individual, group and societal determinants of breast-feeding (Table 2). All methods were conducted concurrently (Fig. 1), except focus groups which started 2 months later because we needed more time for recruitment. We were interested in focusing on the meaning women give to the breast-feeding experience as well as the social contexts that inform and structure personal experience. We took elements from phenomenology and feminism theory to collect and analyse data; for example, the focus group script for mothers was designed to investigate different aspects of the subjective breast-feeding experience such as motivations, expectations v. realities, obstacles and practices. We used open-ended questions to incentivize women to speak freely about their experience. The focus group script for fathers asked about: (i) their expectations and those of other people for them when having babies; (ii) changes in the relationship with the mother; (iii) breast-feeding in public; and (iv) ideas of machismo and gender roles. The theme of gender roles was also explored in the interview script with key informants such as health-care personnel and psycho-social professionals.

Fig. 1 Flowchart showing the dynamics of study data collection, analysis and validation (IFI, infant feeding industry)

Table 2 Qualitative methods used to assess breast-feeding determinants according to socio-ecological framework

Promotora, community health worker; FG, focus groups; IKI, interviews with key informants.

A total of 129 individuals took part in the study: 104 were mothers (n 66), fathers (n 11) and grandparents (n 27) and twenty-five were key informants in health services, day care, the food industry and psycho-social areas. There were six focus groups (three with mothers, one with fathers, one with grandparents, one with mothers and fathers) that varied in size from five to twelve participants. Most of the focus groups (n 5) were conducted in community centres and one was conducted in a day-care centre.

Focus groups and interviews

We recruited low-income mothers, fathers and grandparents for a series of focus groups and interviews at four communities in East Tijuana (Florido, Mariano Matamoros, Terrazas del Valle, El Niño). Community health workers (promotoras) recruited participants for focus groups complying with the inclusion criteria: mothers, fathers and grandparents of children <5 years of age living in one of the four selected areas. Infant feeding history was not specified in the inclusion criteria as the objective was to gather information from the general population. As compensation for participation each promotora was given a $US 15 store gift card at the end of the focus group discussions. Neither focus group nor interview participants received compensation to minimize bias, per the recommendation of local social researchers. To encourage free expression by participants, the focus group facilitator was a non-governmental health-care provider (lead author). Focus groups lasted between 50 and 120 min.

For interviews, potential participants were approached at waiting areas of health-care clinics belonging to the Minister of Health. Interviews were conducted by the lead author (female) and a male research assistant. The lead author was trained in qualitative methods and trained the male research assistant who interviewed the fathers and grandfathers. Bias was minimized by having a semi-structured script guide and by respondent validation. The interviews were conducted whenever study participants meeting study criteria indicated the willingness to do so. Interviews lasted between 20 and 40 min.

At the start of each focus group or interview, we obtained verbal consent from all participants and they were asked to complete a short, demographic questionnaire. Focus groups and interviews continued to be conducted until no new information was obtained from mothers at focus groups and interviews. The point of saturation was determined based on results obtained from mothers as they were our primary focus of interest. The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California Davis (Project # 272118-1) and the Department of Health of the State of Baja California. Only the principal investigator and two research assistants had access to the full tapes. The names of the participants were separated from the transcriptions and field notes, and kept in a locked drawer to which only the leading author had access.

Script guide

Based on the socio-ecological framework, we created a script guide for focus groups and interviews. Questions were reviewed by three members of the University of California Davis research staff and three promotoras working in these communities. The following areas were explored in the script for mothers:

-

1. knowledge about infant feeding recommendations;

-

2. reasons mothers generally choose to breast-feed or formula-feed their infants;

-

3. their own infant feeding intentions before the birth of their babies and their actual practices after their babies were born;

-

4. factors that influenced their actual infant feeding practices after their infants were born, including influential beliefs, persons and events; and

-

5. suggested strategies/interventions to promote breast-feeding at the community level.

Most of these questions were used for the other participants and we added more questions tailored to specific populations (e.g. for physicians we asked what breast-feeding training they received at school/work). We made some modifications to the script based on responses received during previous interviews and focus groups.

We only asked about breast-feeding in general, with no categorization of different types of breast-feeding outcomes, e.g. breast-feeding initiation, duration and exclusivity. Prompts were used, such as in the following example: ‘What are the most important reasons for women to decide to use formula? Or for not breast-feeding?’ The prompts used were: ‘because of work’, ‘hospital practices’, ‘health-care professionals’, ‘family/community support’, ‘individual health issues’.

Interviews with key informants

Twenty-five key informants, among health-care providers, members of non-governmental organizations, nutrition/health educators, psychologists, sociologists, day-care-centre staff and infant food industry representatives, were approached by the leading author to take part in the study. We included at least one health-care professional with experience working in breast-feeding support and programmes from each of the five health-care services in Tijuana (IMSS, ISSSTE, ISSSTECALI,Footnote * Minister of Health and private institutions). Some key informants were health-care professionals with more than 10 years of experience with breast-feeding support at the prenatal and postnatal level, others were health-care professionals coordinating the breast-feeding centre at their hospital/clinic and some were community workers with breast-feeding promotion experience (promotoras). Key informants were interviewed in a private room at their offices, with only the researcher present. Interviews lasted between 30 and 90 min. Notes were taken during the course of the interview.

Observations

The leading author was actively present at health-care centres. For one year, observations in the maternal–infant services at general hospital and local health clinics were carried out to allow immersion in the field and culture and to understand the usual practice and processes linked to infant feeding practices. The observations were recorded as field notes and were transcribed and coded, along with the other qualitative data.

Document analysis

This consisted of a review of health-care policies, influence of the food industry, abiding by the international code of marketing of breast-milk substitutes, breast-feeding policies at work and maternity laws.

Data analysis

Focus groups were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interview and observation notes, document analysis and focus group transcripts were then studied in depth as a whole, independently by three researchers. Thematic analysis followed the approach specified by Pollio et al.( Reference Pollio, Henley and Thompson 25 ). Each of the three researchers extracted the main themes, phrases and meanings of the participants’ words as they related to mothers and breast-feeding within the socio-cultural context of the mothers’ lives. The primary analytical technique was constant comparison( Reference Krueger 26 , Reference Leech and Onwuegbuzle 27 ). Maternal focus group data were the first analysed. We selected the main themes and sub-themes and labelled them with a code. Then we analysed data from fathers, grandparents and other key informants. Most of the meaningful comments could be categorized within the previous themes and sub-themes; if they could not, we added additional themes/sub-themes. We also used classical content analysis in which the researcher counts the number of times each code was utilized. The factors taken into account to classify themes were the frequency, extensiveness (how many different people say something as opposed to how many times by the same person) and emotion. Other analytical techniques used only with mothers were word count, keywords in context and connecting networks.

We used the following strategies to increase validity( Reference Maxwell 28 , Reference Maxwell 29 ).

-

1. Intensive, long-term involvement: we attended over the course of a year to the general hospital and the four community settings at clinics and community centres.

-

2. Rich data: we had verbatim transcripts from focus groups and detailed, descriptive note-taking from interviews and observations.

-

3. Triangulation: we collected information from a diverse range of individuals and settings, using a variety of methods to reduce the risk of chance associations and systematic biases.

-

4. Respondent validation: we returned to the communities to conduct one focus group and twenty-three interviews to communicate our findings and ask for feedback. After initial data analysis, we presented the results of the main obstacles to breast-feeding to a group of mothers and asked them if they represented what they encounter in the community. We also requested they rank the ten main breast-feeding obstacles.

Results

A summary of the parents’ and grandparents’ sociodemographic characteristics obtained using the pre-interview questionnaire may be found in Table 3. We did not ask about health insurance status but some mothers offered information during focus groups or interviews. Based on information many mothers provided, approximately half of them attended IMSS (formal employment) and half of them attended at the Minister of Health (general public), with some of them receiving services in both institutions.

Table 3 Sociodemographic characteristics of participants from low-income communities, Tijuana, Mexico

Maquiladora, assembly factory.

* Percentage is for individuals with known information.

Themes

A total of twenty-two major themes/obstacles were identified among comments of all participants (Table 4). Major themes were further classified as individual, group, societal or intervention factors. In the current paper we discuss societal themes. The seven societal factors were: (i) migrant experience; (ii) breast-feeding in public; (iii) status/cost; (iv) gender roles; (v) the infant food industry; (vi) social programmes; and (vii) food culture in Mexico. In a continuing phase of the study (D Bueno-Gutierrez and C Chantry, unpublished results) we returned to the communities to validate findings and asked mothers to rank the ten main obstacles to breast-feeding. Social factors were ranked as tied for number 3/4 (breast-feeding in public) and 9 (formula culture; Table 5).

Table 4 Major themes from thematic analysis

Table 5 Breast-feeding obstacles ranking

Themes and representative quotes/words supporting each theme are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6 Themes, quotes and words related to social determinants of breast-feeding in the study population from low-income communities, Tijuana, Mexico

FG, focus group; LC, lactation consultant; IKI, interview with key informant; I, interview; Doula, a person offering non-medical support and information to parents in pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal period; IMSS, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (Mexican Social Security Institute).

* To achieve semantic equivalence, quotes were translated to English by a professional translator and back-translated to Spanish by another professional translator.

Migrant experience: traditional and/or modern ideas

The majority of the migrant mothers who participated in the study placed a positive value on breast-feeding: they knew about its benefits and at least initiated breast-feeding. However, they commented on the struggle to continue breast-feeding in a culture that is not breast-feeding-friendly, as one participant said: ‘Life doesn’t make it easy to breast-feed’. Some participants used the term morbo, morboso or morbosidad to refer to how breast-feeding is seen in Tijuana. This term means an unhealthy interest or interest for something morally wrong or for disturbing acts (e.g. related to sex, disease or death).

Over 50 % of this population is migrant and therefore many women commented about the change of life from their places of origin, which generally were smaller, semi-rural, where life is quieter and breast-feeding is looked upon as more ‘normal’ and is more appreciated as ‘natural’. The moment they arrive in Tijuana they notice that life is faster and people eat more processed foods. Comfort is sought out. Some describe Tijuana as more modern compared with southern Mexico and feel the need to adapt to the new ideas. Some see breast-feeding as old fashioned or ‘something their grandmothers did’. Some commented that in their hometowns people are deeply rooted, secluded and closed-minded. Some expressed nostalgia to return to their traditional ideas.

Breast-feeding in public

Breast-feeding is seen as a behaviour that can be done in private but not in public spaces. Most of the women interviewed reported feeling uncomfortable and embarrassed/ashamed while breast-feeding in public. They feel observed, especially by men. On the other hand, they criticized women who do not cover well (‘modesty is being lost’) and mentioned that in Tijuana there is more morbosidad than in other places.

Fathers also mentioned feeling uncomfortable when their partner or any woman breast-feeds in public because of the ‘morbidity of people’ or due to jealousy. There were other ideas of ‘machismo’ (concept associated with traditional ideas about a masculine sense of pride and male domination over women) influencing breast-feeding in public, such as men thinking women’s bodies belong to them and no one else is entitled to see their breasts.

Status/cost

Most families are aware of the high cost of formula and some, especially men, take it into consideration when decisions about infant feeding are made. However, social pressure for both men and women, to be seen in a higher status by using formula, seems to weigh more. Additionally, breast-feeding is perceived as an activity of the indigenous groups and since they are discriminated against, it is perceived as having higher ethnic status if a mother does not breast-feed.

Gender roles

In Mexico the notion is present that child care, and therefore the decisions on how to feed children, is the obligation of the mother. This can be an obstacle to breast-feeding when it is assumed that mothers naturally can and must solve any problem and do not need support from fathers or other members of the family and social system. Another obstacle to breast-feeding relates to the sexualization of women that can be focused on the breasts or in the fact of treating the woman’s whole body as an object. These ideas were seen in comments made by mothers, fathers and grandparents and are extended to the health staff when it is assumed that nurses or female doctors will fulfil the role of explaining to mothers how to breast-feed, just because they are women. A major influence in perpetuating these ideas is through television and soap operas.

It is interesting to note that when mothers were asked about their occupation they responded homemakers when they were not employed, unlike men who responded unemployed (Table 2). Machismo is very present especially in individuals of low socio-economic and educational level as they have less information and the environment does not facilitate change because of pressure from others. If he tries to get more involved with child care, the father can be labelled as mandilón (mama’s boy) or ‘getting into women’s things’. Individuals with a higher educational level have more information, so they know more about the benefits of breast-feeding with respect to health as well as economic advantages; there is also a ‘macho’ environment, but they have more resources to stand their ground.

Gender roles and migration factors interact to influence infant feeding practices in these communities. Parents mentioned having perceived less machismo in Tijuana than in their hometowns, located usually in the south of the country. However, mothers talked about new forms of machismo in this new environment adapted to modern times. Currently, men understand more the fact of women working outside the home but only in certain justifiable cases, for example when money is needed at home. Also some men support women more in the private sphere but not in public. All these issues create the particular mix of social obstacles to breast-feeding in this population, e.g. some fathers (especially those who are younger) try to share more parenting care responsibilities with their partners, but are still constrained by social expectations of not being seen by others as helping women with domestic matters or allowing them to breast-feed in public.

Fathers also reflected on the changes that occur in couples when children enter the family and how this may also influence gender roles. They considered that even though the priority must be the child, there are some men who do not understand this and complain about not being attended to by his wife anymore.

Men expressed their desire to participate more in decisions and care for their children, but there are obstacles for this to occur, such as women or health programmes do not include them in decisions and promotional activities. The economic aspect of breast-feeding seems to be the way fathers are starting to get more involved in supporting mothers to breast-feed.

Infant food industry

This topic was mentioned predominantly by key informants. The subject of the influence of the infant food industry (IFI) on health-care services is discussed elsewhere( Reference Bueno-Gutierrez and Chantry 30 ). Here we elaborate on other social aspects.

The beginning of the IFI in Latin America was discussed in one key informant interview. The participant commented that IFI found a fertile environment to promote their products in a generation that said ‘no’ to breast-feeding and a culture with beliefs about emotional distress transmitting to their children by breast milk.

IFI representatives know that paediatricians have the power to persuade mothers; thus their target populations are paediatricians and general practitioners. They receive periodic training and know the recommendations of international paediatric associations. IFI staff members organize seminars and continuing education for physicians, bringing specialists to discuss the nutrition issues that most frequently require specialized formulas. The promotion is aimed at new ingredients, mainly in the area of PUFA and probiotics and how these help infants’ neurological development. The IFI leverages feedback from doctors about what formulas are currently needed. The main requests of paediatricians are modifications to formulas routinely for children with lactose intolerance, reflux and colic.

One of the suggested ways to persuade parents to purchase these products is to promote a sense of guilt to make them see that they do not spend enough on the health of their children by feeding them ‘properly’ while on the other hand they do spend more on clothing, shoes and diapers, which ‘they never see again’. In addition, they exploit the ideas of status granted by the purchase of formula. Infant food companies also sell the idea that breast-feeding is more time consuming than formula feeding, thus targeting modern women, those working outside the home and those lacking family and social support.

Another way to promote their products is through written educational material left in the waiting rooms of doctors’ offices. Sometimes they develop informative material about some health problems such as allergies to milk proteins and how to solve the problem with the right formula. That way they know that worried mothers may ask the paediatrician about these products.

Social programmes

There is no programme or policy that promotes breast-feeding at the national or local level. Usually the subject is treated as a woman’s responsibility and therefore if a woman does not breast-feed it is because she does not want to, without taking into consideration the various different factors influencing such decisions. Additionally, there is a double standard where breast-feeding is encouraged but not supported and conflicting messages that promote infant formula are expressed.

There are two practices that are carried out as part of social programmes that were mentioned in the interviews as particularly hindering breast-feeding:

-

1. Providing formula at IMSS. The IMSS is a social security institution for formal workers; thus participants (mothers, family members, key informants) mentioned that there is a perception about the right or benefit for mothers to receive formula. In addition, some mothers were offered formula before talking about breast-feeding benefits. Even if the mother said that she did not want formula, some health-care professionals insisted about her rights and/or that maybe with only breast-feeding the baby would not be satisfied.

-

2. The Liconsa milk. This is a fortified milk that is given free of charge to pregnant women and mothers of children under 5 years as part of a federal government programme. The guidelines of the programme state that it is milk suitable for children over 1 year old (whole milk). But families think that since it is fortified milk, it also can be given to babies under 1 year.

Food culture in Mexico

Participants from the present study expressed living in a formula culture. Breast-feeding as a culture is perceived as getting lost in Mexico and fewer and fewer women have seen other women breast-feeding. There is the idea that there is a formula culture that is associated with modern life, where one cannot keep up with all the activities to be performed throughout the day. The formula is the kind of artificial food that can provide comfort. As the baby grows the formula is replaced or supplemented with other artificial foods. By accustoming the child to eat these foods, later it is very difficult to change these habits and Mexicans continue to consume cheap, processed foods with high energy density and little nutritional value.

There are also other cultural beliefs about breast-feeding in modern life. Some participants reported that many people see breast-feeding as a behaviour performed by women who are at home and do nothing. There are some social practices such as giving bottles at baby showers and even in everyday lexicon it is common to use the phrase when you know someone is pregnant: ‘You will have to change diapers and give them the bottle’.

Mothers reported early introduction of complementary feeding. This can be fostered by beliefs that babies should be fat in order to be healthy and that love enters through the mouth, so they may think that breast-feeding is not enough and it is necessary to add other foods.

Opportunities/interventions at the societal level to improve breast-feeding rates

The most common recommendations for social interventions to promote breast-feeding from participants of the present study were as follows.

-

1. School activities: use junior and high schools so that students start being aware of breast-feeding. In addition, use schools for other activities and classes for the general public.

-

2. Home visits: for the people who did not attend the community activities who may be the ones at higher risk for not breast-feeding.

-

3. Cultural breast-feeding support: need to see more people breast-feeding in public; mothers should look more for information about breast-feeding; mothers should receive more social support to breast-feed; breast-feeding should be promoted on television and in other media.

-

4. Integrate with existing programmes, such the ones they are already familiar with. For example, mothers with children less than 5 years of age from one focus group were part of a community programme to increase academic performance of children and they could take advantage of learning about infant feeding.

-

5. Getting young people involved in breast-feeding promotion and support.

-

6. Getting fathers involved: taking into account community programme times according to their work schedule.

-

7. Having a toll-free telephone number for individualized breast-feeding information and support.

-

8. Community activities supported by someone with medical authority, e.g. an intermediate-level provider such as nurses or health promoters or educators.

-

9. Have an educational campaign about the different ways to extract milk and the different devices.

Discussion

We found various social factors affecting breast-feeding in this population. Some of these factors, such as breast-feeding in public and the influence of the IFI, are common to other cultures( Reference Scott and Mostyn 31 – Reference Raisler 38 ). However, infant feeding practices in this migrant population are particularly influenced by the cultural clash of confronting traditional ideas acquired in small, rural towns with the modern ideas of the big city bordering the USA. Other Mexican beliefs and practices such as early complementary feeding, the predilection for a chubby baby and gender roles that determine that infant feeding is the mother’s responsibility can also have detrimental effects on breast-feeding.

The cultural clash observed in these communities is representative of the nutritional and epidemiological transition underway in Mexico( Reference Rivera, Barquera and Campirano 39 ). In southern and rural areas, where traditional practices are the norm, there are higher breast-feeding rates than in the northern, more urban, modern environments. There are other studies indicating that breast-feeding rates are decreasing in women migrating from traditional, rural areas to modern, urban societies with higher income( Reference Schmied, Olley and Burns 40 – Reference Pérez-Escamilla 42 ).

Modernization implies acculturation or adoption of the values, beliefs and behaviours of the mainstream society( Reference Sam and Berry 43 ). Acculturation studies show that individuals vary in the levels to which they maintain their original culture and adopt the practices of their new environment( Reference Veile, Martin and McAllister 41 – Reference Harley, Stamm and Eskenazi 46 ). In a study conducted among low-income Latinas in the USA( Reference Chapman and Pérez-Escamilla 44 ), a multidimensional assessment of acculturation showed that the best breast-feeding outcomes were observed in a low-integrated group, which scored low on both the Hispanic and the American scales, followed by the group of traditional Hispanics. The groups that were most likely to discontinue breast-feeding were those that scored higher on the American subscale (the highly integrated and assimilated groups).

A similar behaviour can be happening in Tijuana where acculturation is taking place for many women arriving to this urban, border area with more US influence. Women who have just arrived and preserve their traditions are more likely to breast-feed than women who have more years living in Tijuana and want to embrace the practices of the new environment. This is in line with other behaviours in a region experiencing a nutritional transition, such as more access to inexpensive but highly energy-dense foods and decreased physical activity in urban, more developed industrial states (North Mexico)( Reference Rivera, Barquera and Campirano 39 , Reference Harley, Stamm and Eskenazi 46 , Reference Frenk, Frejka and Bobadilla 47 ).

Breast-feeding in public

Breast-feeding in public is one of the obstacles noted in the present and other studies conducted in Mexico( Reference Olaiz-Fernández, Rivera-Dommarco and Shamah-Levy 9 , Reference Guerrero, Morrow and Calva 48 , Reference Gulino and Sweeney 49 ), in the Hispanic population in the USA( Reference Babington 50 ), in migrant populations( Reference Schmied, Olley and Burns 40 ) and in other populations( Reference Burns, Schmied and Sheehan 51 ). In the present study it was ranked as the third main obstacle to breast-feed (D Bueno-Gutierrez and C Chantry, unpublished results). Mothers talked about feeling uncomfortable, embarrassed or ashamed to breast-feed in public.

Social embarrassment has been cited as a relevant obstacle to breast-feeding in other low-income populations( Reference Scott and Mostyn 31 , Reference McIntosh 32 ). When we asked about their place of origin in our study, it was noted that women in rural environments breast-fed in public and people see it as something natural. However, in Tijuana people are more ‘morbid’. Feeling embarrassed by breast-feeding when others are present has been reported by migrant women as a reason to formula feed or to use mixed feeding( Reference Choudhry and Wallace 52 ). Latino mothers in the USA emphasized that breast-feeding in public made them feel uncomfortable( Reference Babington 50 ).

Some women expressed their spouse’s discomfort with the possible exposure of their body in public. Fathers also mentioned feeling uncomfortable when their wives would breast-feed in public as well as when other women breast-feed in public. They said that many men take this opportunity to see the woman’s breasts. This has been referred as the ‘male gaze’( Reference Stearns 33 ) and women feel objectified and positioned as engaging in inappropriate sexual display( Reference Zeitlyn and Rowshan 34 , Reference Schmied and Lupton 35 ). In a study conducted among low-income British men( Reference Henderson, McMillan and Green 36 ), several fathers expressed ‘embarrassment’ when they were asked about what they think when they hear the word ‘breast-feeding’.

Some participants from the present study associated breast-feeding with an intimate activity that is done in private and thus it is hard to do it in public. This also has been mentioned in other studies( Reference Dowling, Naidoo and Pontin 37 , Reference Raisler 38 ). Public space reflects a moral order and according to Goffman (as cited in Brouwer et al.( Reference Brouwer, Drummond and Willis 53 )), ‘rebelling against the social mores that disapprove breastfeeding in public would stigmatize mothers and construct them as social deviants’.

Status/cost

Mexico is a class-conscious society. In our study we observed that even when participants knew about formula costs, the idea that giving formula gives you a higher social status persists, resulting in people thinking that you are wealthy if you will try to use formula. In other studies( Reference Sobel, Lellamo and Raya 54 , Reference Guttman and Zimmerman 55 ) it has also been noted that even when women are low-income, the ones who provide formula do not think that the monetary cost is important.

Gender roles

In Mexico’s patriarchal culture, breast-feeding is considered as something that is ‘natural’ and ‘given’ for mothers and as a result, something pleasant and unquestionable( Reference Cardaci 56 ). Many women in the present study expressed that men do not participate in infant feeding decisions and other aspects of infant care. Pederson (as cited in Gamble and Morse( Reference Gamble and Morse 57 )) suggests that ‘the lack of emotional support of fathers may be due to sex role stereotypes that define the father as strong and the mother as weak’. Furthermore, fathers said that the couple relationship changes after childbirth. They may feel excluded from the mother–baby relationship and can experience feelings such as jealousy( Reference Bartlett 58 , Reference Pisacane, Continisio and Aldinucci 59 ). These conflicts may disrupt breast-feeding. Mothers with an unsupportive partner may experience a lack of self-confidence and feel pressured to stop breast-feeding( Reference Waletsky 60 , Reference Kearney 61 ).

There are more fathers who want to be involved in their children’s care in this population. Sometimes fathers feel that women themselves hold them back and make them feel as they don’t know what they’re doing. Another problem is fathers not being included at health services’ programmes. Additionally, they feel awkward going to group sessions where there may be only women. This could be addressed by using male educators such as in the community-based educational intervention in a Turkish group of fathers that proved to be effective to attract more men( Reference Turan, Nalbant and Bulut 62 ).

Infant food industry

The IFI knows that doctors are influential figures for mothers. Participants in the present study reported that doctors are continuously influenced by IFI representatives.

Additionally, formula feeding is sold as the best option for modern women, providing mothers more ‘comfort’ and ‘freedom’ with a more ‘scientific’ alternative that allows them to quantify the milk consumed and to have more ‘control’( Reference Guttman and Zimmerman 55 ).

Food culture in Mexico

In Western countries it is possible that a new mother has never seen a woman breast-feed in public. Some participants from the present study expressed living in a formula culture. A study conducted in the more deprived areas of Glasgow, Scotland( Reference Scott and Mostyn 31 ) also found that formula feeding was the prevailing social norm. Women wanting to breast-feed in these areas had little or no prior exposure to breast-feeding and often received little support from family and friends.

The exposure to breast-feeding is critical to return to a breast-feeding culture. Hoddinott and Pill found that this ‘embodied knowledge’ can be more influential for women from lower socio-economic groups than theoretical knowledge to produce confidence in the ability to breast-feed( Reference Hoddinott and Pill 63 ).

Mothers also noted the formula culture derives from the sense of a need for convenience in a fast-paced society and use of this artificial food in infancy is followed by subsequent use of pre-packaged ‘artificial’ convenience foods. It is interesting to note that an association between formula feeding and lower acceptability of fruits and vegetables since infancy has been previously reported( Reference Menella 64 ) and may also be shaping the subsequent family food choices.

Study limitations

The findings from the present study do not necessarily apply to a larger population of mothers, even those meeting the eligibility criteria for our study. Mothers from this convenience sample were recruited by promotoras, they were mostly migrant, multiparous and low-income homemakers. Our findings were based on self-reported behaviour. They are dependent upon the participant’s recollections of breast-feeding events, associated feelings and socially acceptable behaviours. We only asked about breast-feeding obstacles in general, thus there is a lack of ability to discriminate for different types of breast-feeding outcomes.

The findings on morbosidad were encountered in data analysis and there was inadequate time to further explore the concept. We believe this is an important finding that merits further exploration.

Study strengths

One strength of the current work is the border context where traditional and modern ideas that affect breast-feeding practices clash. We collected information from a diverse range of individuals (mothers, fathers, grandparents, health-care providers, day-care personnel, experts on sociology and psychology, food industry personnel) and settings (community centres, clinics, hospitals, academic institutions) using a variety of methods (focus groups, interviews, observations) and data analysis (organizational and theoretic categories) by different people (three researchers) to reduce the risk of chance associations and systematic biases due to a specific method. This is also known as triangulation and it is applied as a strategy for validity in qualitative research. If you only use one qualitative method, you may only have one view about breast-feeding, which could be influenced by socially accepted responses in the case of just using focus groups or by other sources of bias, e.g. recall bias, respondents who have changed their mind or a misinterpretation in the transcription. But if you also use other methods such as interviews, observations and document analysis, you will have a more reliable way to discern multiple dimensions in a reality where people may be inconsistent.

We also returned to the communities to conduct one focus group and twenty-three interviews to communicate our findings and ask them for feedback. They validated our findings and help us ranked the ten main obstacles to breast-feeding to be used for educational message design (D Bueno-Gutierrez and C Chantry, unpublished results).

Conclusions

Socio-structural factors influence infant feeding practices in low-income communities in Tijuana. These factors must be considered when planning integral interventions to promote, support and protect breast-feeding in this population. Promotion of breast-feeding must be comprehensive, combining education by medical practitioners sensitive to women’s cultural and social background, and support by the family, peers and the community( Reference Perez-Escamilla, Curry and Minhas 65 ).

Breast-feeding in public makes people uncomfortable. Nursing mothers are stressed by the numerous social norms with which they must comply. Promotion of breast-feeding in public must take into account the power of social judgement due to the sexualization of breasts in Western societies, the ‘male gaze’ and the moral order of public space.

Re-establishment of a breast-feeding culture must occur to optimize the health of the population. Messages emphasizing traditional Mexican along with modern healthy practices may allow normalizing breast-feeding in this population. Choudhry and Wallace (as cited in Schmied et al.( Reference Schmied, Olley and Burns 40 )) ‘suggest that if migrant women had the opportunity to observe peers from the dominant culture engaging in breast-feeding, it may help redress the misconceptions that modern women do not breast-feed’.

Awareness of the cultural and social breast-feeding determinants in the population served provides a basis for the most appropriate advice and support to promote breast-feeding, based on the barriers faced. ‘The practice of breast-feeding must be seen as a right and a true choice for all women, not a privilege( Reference McMcCarter-Spaulding 66 )’.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge Lucia Kaiser and Yvette Flores for helpful suggestions after manuscript review; Teresa Ewell for translation support; Iliana Castañeda from the Minister of Health in Tijuana, Fronteras Unidas Pro-Salud and Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (UABC) for logistical and data collection support. Financial support: This work was supported by Centro Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT), Mexico and the Inter-American Fellowship (IAF) Grassroots Development, USA. Both organizations had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: D.B.-G. is the lead author and had main responsibility in formulating the research questions, designing the study, carrying it out, analysing the data and writing the article. C.C. made a substantial contribution to conception and design of the study, analysis of the data, critical revision of the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. Ethics of human subject participation: The study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California Davis (Project # 272118-1) and the Department of Health of the State of Baja California.