Mothers’ key influence on children’s diet

In Canada, adherence to national healthy eating recommendations, including the consumption of sufficient amounts of vegetables and fruits and milk and alternatives to achieve a healthy and balanced diet and reduce the risks of obesity and chronic diseases, is poor in both adults and children(1,Reference Garriguet2) . Mothers play a primary role in promoting healthy eating to their children, especially in preschool and school-age children for whom the family home food environment is an important determinant of eating behaviours, food intake(Reference Mazarello Paes, Ong and Lakshman3), food preferences and acceptance patterns(Reference Birch4). Therefore, targeting mothers of young children in healthy eating promotion interventions has the potential to generate additional benefits for their children’s diet and health outcomes. Mothers generally undertake primary responsibilities for purchasing food and planning and preparing meals for their family(Reference Hartmann, Dohle and Siegrist5–Reference Fielding-Singh7). Mothers are also the person from whom children most often learn to cook(Reference Lavelle, Spence and Hollywood8). There has been a growing interest from the scientific community in understanding how mothers can promote healthier lifestyles in their children. For instance, international studies have identified time constraints (e.g. lack of time to prepare home-cooked meals and difficult timing of family meals when working full time)(Reference Mazarello Paes, Ong and Lakshman3,Reference Hayter, Draper and Ohly9–Reference Spence, Hesketh and Crawford11) and children’s taste preference (most particularly disliking the taste of vegetables)(Reference Nepper and Chai12) as barriers to providing healthy foods to young children. In Canada, little is known on the food-related practices used by mothers and their associations with young children’s dietary intake(Reference Watterworth, Hutchinson and Buchholz13). Furthermore, no study has yet investigated the perceptions of Canadian mothers on the reasons why they adopt a healthy diet, such as one rich in vegetables and fruits and milk and alternatives, and why they provide healthy foods to their children.

eHealth/mHealth and maternal and child nutrition

Innovative interventions conducted over the Web (eHealth) and mobile technologies (mHealth) targeting mothers have demonstrated success in promoting healthier child feeding practices and children’s higher exposure to fruits and vegetables(Reference Russell, Denney-Wilson and Laws14–Reference Gruver, Bishop-Gilyard and Lieberman17). Although they could be promising tools to improve health behaviours and health-related outcomes, eHealth and mHealth interventions are associated with specific challenges. For instance, the evaluation of the impact, reach and implementation of those interventions is complexified by high attrition(Reference Eysenbach18), low engagement of users with behaviour change tools(Reference Olson, Groth and Graham19) and, in some cases, technical issues(Reference Litterbach, Russell and Taki20). For all health promotion interventions, including complex eHealth and mHealth interventions, process evaluations are essential to understand the fidelity and quality of implementation, explain the mechanisms of impact and identify contextual factors associated with variations in outcomes(Reference Moore, Audrey and Barker21,Reference Bartholomew Eldredge, Markham and Ruiter22) . Process evaluation studies using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods have been conducted to understand factors influencing engagement and behavioural determinants in eHealth and mHealth programs, to understand programme effects (Reference Litterbach, Russell and Taki20,Reference Partridge, Allman-Farinelli and McGeechan23) , passive use (i.e. lurking, an online behaviour characterised by reading other users’ postings and messages on an online community without actively participating in that community by posting or writing content) of programme components(Reference Merchant, Weibel and Patrick24), overall participants’ satisfaction,(Reference Laska, Sevcik and Moe25) and acceptability(Reference Hutchesson, Callister and Morgan26) of programmes. Such evaluations provide guidance for the design and conduct of future interventions to maximise behaviour change and effectiveness.

The healthy eating blog trial

A prospective randomised controlled trial investigated the efficacy of a healthy eating blog to improve dietary habits and food-related behaviours of mothers and their children. This trial was conducted with adult mothers of 2–12-year-old children living in the Quebec City metropolitan area, Canada, from 21 January 2016 to 13 September 2017. The full trial protocol (Clinical Trial Protocol NCT03156803) and details about the development of the blog have been published elsewhere(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe27). Briefly, mothers were randomised to an intervention delivered exclusively through a private healthy eating blog at a dose of one new entry (post) published each week on the blog by a registered dietitian (RD) during a 6-month period (n 42), or to a control group (n 42) with no exposure to the study blog. The control group was not offered specific dietary advice or counselling during the intervention period, but met with the research coordinator to complete outcome assessment. The primary objective of the blog was to increase the daily consumption of vegetables and fruit and milk and alternatives of mothers and their children. No evidence of differences was found in mean dietary intake in mothers exposed to the blog and their children as well as other food-related outcomes (eating behaviours, meal planning and cooking skills and attitudes and food parenting practises) and body weight compared with the control condition at the end of the intervention(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe28) and at a 12-month follow-up(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe29). On average, mothers visited the blog once a week, but the posting of comments on the blog was modest throughout the intervention (mean of 0·2 comment/participant/week)(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe28). Weekly logins to the blog decreased during the first half of the intervention to finally plateau - except for a few random peaks of logins - during the second half of the intervention(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe28).

Study aims

The main objective of the current study was to conduct a process evaluation of the healthy eating blog trial in order to gain a deeper understanding as to why the blog had a null impact on food-related outcomes and how mothers perceived the intervention. Using a mixed-method methodology, the current study specifically sought to explore mothers’ perceptions underlying (1) the blog’s usefulness to improve their dietary habits - most especially to increase their consumption of vegetables and fruit and milk and alternatives and the promotion of those foods to their 2–12-year-old children -, and (2) barriers and facilitators that influenced their dietary behaviours and engagement with the blog, including their most and least appreciated blog characteristics.

Methods

Study participants

The healthy eating blog trial was conducted with adult mothers of 2–12-year-old children and living in the Quebec City metropolitan area. Mothers had to be primarily responsible for food purchase and preparation in the household and consume fewer than the recommended daily servings of vegetables and fruit and/or of milk and alternatives food groups in the Canadian dietary guidelines in force when the study was initiated(30) on a recalled day (i.e. fewer than 7 servings per day of vegetables and fruit and/or fewer than 2 servings per day of milk and alternatives). As described in detail elsewhere(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe31), women who were pregnant or breast-feeding, those who suffered from an eating disorder and those taking medication that could influence their body weight or food intake were excluded. Recruitment was conducted between October 2015 and February 2017 using institutional (e.g. affiliated university and research centre) email lists, flyers, newspapers, advertisements on blogs, Twitter and Facebook and word of mouth. Mothers were not blinded and knew the purpose of the research. Among the 196 interested mothers who responded to our recruitment call, forty three declined to participate in the study after they received full information about the nature of their participation and sixty six did not meet the eligibility criteria. Among the eighty-seven eligible mothers, three mothers did not attend their first in-person outcome assessment appointment resulting in a final sample of eighty-four mothers randomised to the study.

Intervention components

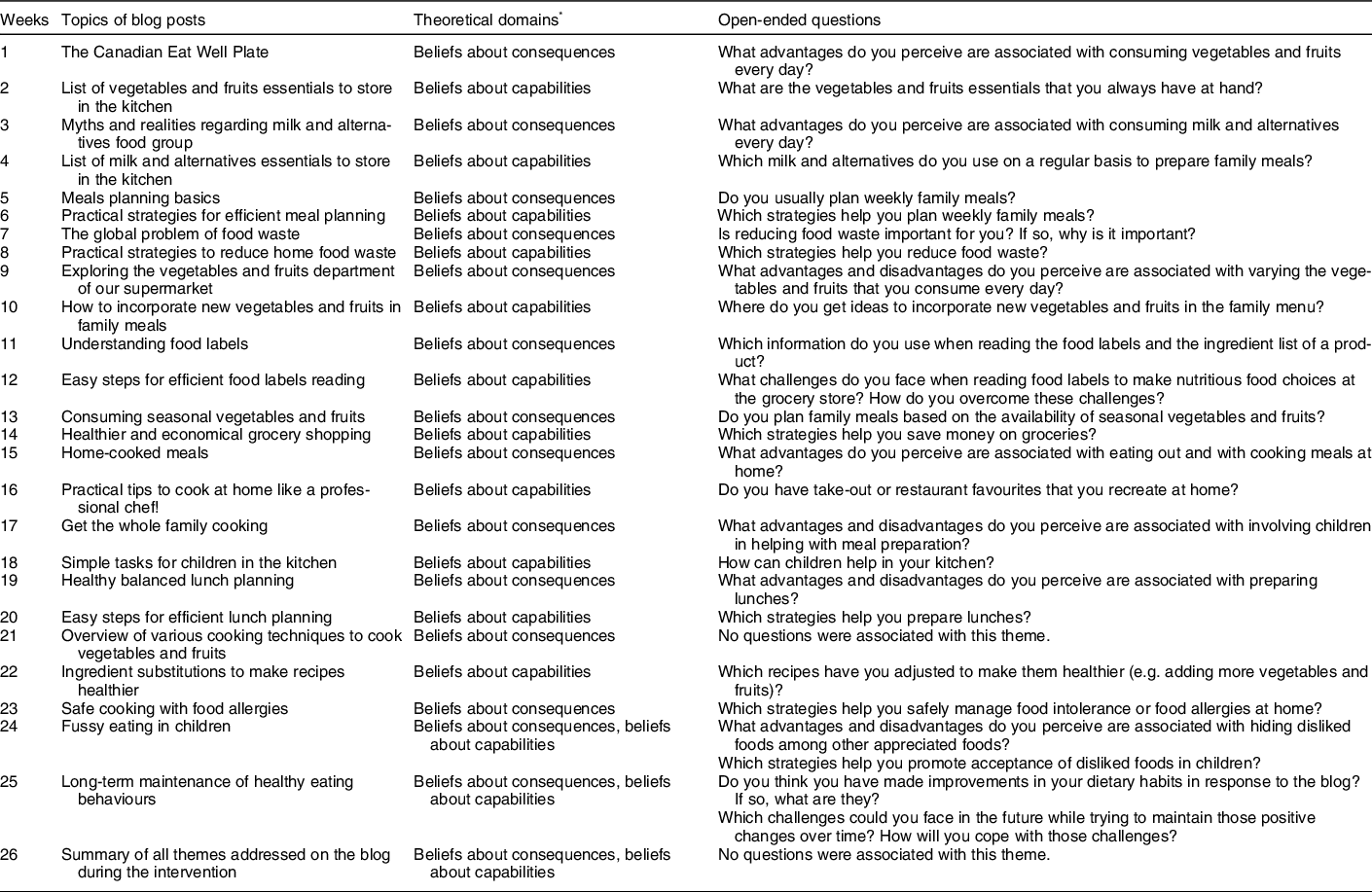

The intervention was conducted over a 6-month period at a dose of one weekly blog post written by an RD published on the blog for a total of twenty-six blog posts. As described elsewhere(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe27), the blog was hosted on the WordPress™ blogging platform. The RD-blogger (first author) was a female PhD student in nutrition with a 5-year experience as a healthy eating blogger. She was not known to study participants prior to trial onset and she had perused training in theories and techniques of health behaviour change. Blog posts were designed to integrate theory-based intervention methods (e.g. modelling, goal setting and provision of feedback on performance) selected from the Intervention Mapping protocol(Reference Kok, Gottlieb and Peters32) and the Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy v1(Reference Michie, Richardson and Johnston33). The intervention methods were selected based on their effectiveness to influence theoretical domains predicting the consumption of vegetables and fruits and milk and alternatives in adults (i.e. knowledge, beliefs about consequences (e.g. perceptions of advantages/disadvantages), beliefs about capabilities (e.g. perceptions of barriers/facilitators), intention and goals)(Reference Guillaumie, Godin and Vezina-Im34–Reference Wheeler and Chapman-Novakofski38). The intervention logic model of change was published elsewhere(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe27). In brief, it was hypothesised that the mechanism through which the blog would produce change was through changes in the selected theoretical domains, which would influence the achievement of performance objectives (e.g. plan adequately vegetables and fruits and milk and alternatives purchase and meal preparation) to help mothers and their children increase their consumption of vegetables and fruit and milk and alternatives. Each week, mothers were alerted of a new blog posting by email. Each blog post included a step-by-step recipe with pictures featuring vegetables and fruits and/or milk and alternatives. Additionally, each post ended with an open-ended question submitted by the RD-blogger (Table 1) to initiate discussions with mothers about their perceptions of the factors underlying the adoption of a healthier diet. Mothers were encouraged to engage in online discussions with the RD-blogger and fellow mothers using the comment function on the blog (mothers who posted comments on the blog are characterised as ‘posters’ in the present manuscript). Mother-initiated comments were posted anonymously on the blog (mothers were named xblog-X) to encourage participation without apprehensions regarding privacy.

Table 1 Topics addressed in the intervention blog, classified by targeted theoretical domains and open-ended questions of the registered dietitian blogger submitted each week to the healthy eating blog during the 6-month (26 weeks) dietary intervention

* As presented in the Theoretical Domains Framework(Reference Cane, O’Connor and Michie69,Reference Michie, Johnston and Abraham70) the domain Beliefs about consequences is defined as ‘[the] acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about outcomes of a behavior in a given situation’, and includes psychological constructs such as beliefs, outcomes expectancies, and anticipated regret; the domain Beliefs about capabilities is defined as ‘[the] acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about an ability, talent, or facility that a person can put to constructive use’ and includes psychological constructs such as self-confidence, perceived competence and self-efficacy.

Data collection of process measures

Mother-initiated comments on the blog

Comments posted by mothers on the blog were collected continuously throughout the 6-month intervention using the Web analytics plug-in Slimstat Analytics(39) and then grouped into Microsoft Word documents (Microsoft Corporation).

Participants experiences with blog components and perceptions of the blog’s usefulness to improve dietary habits

At the end of the 6-month dietary intervention, mothers randomised to the intervention group completed a self-administered Web-based satisfaction questionnaire. Mothers who completed this questionnaire are characterised as ‘completers’ in the present manuscript. They were asked ten quantitative and two open-ended qualitative questions about their perceptions of the blog’s usefulness to improve their dietary habits, which blog components they found most useful in helping them improve their dietary habits as well as which blog components were the most and least appreciated.

Socio-demographic variables and blog use habits

At baseline, mothers completed a self-administered Web-based questionnaire consisting of thirty-three questions documenting the following socio-demographic characteristics: age, ethnicity, highest education level completed, employment and civil status, annual family income, number and age of children, as well as their blog use habits. The questionnaire was developed and used in a preliminary focus group study (Reference Bissonnette-Maheux, Provencher and Lapointe40,Reference Bissonnette-Maheux, Dumas and Provencher41) .

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and means ± SD or percentages were used to report baseline socio-demographic characteristics of mothers, blog use habits as well as quantitative data from the blog satisfaction questionnaire using SAS University Edition software (SAS Institute Inc.). Participants’ brief responses to the two open-ended qualitative questions on the blog satisfaction questionnaire were coded by one researcher (first author) using a qualitative deductive content analysis approach(Reference Elo and Kyngäs42) (Excel software, Office 365, version 15.40, Microsoft Corporation), into categories that best reflected their perception of the blog’s usefulness to improve their dietary habits, as well as their most and least appreciated blog characteristics. Data coding and analysis of mother-initiated comments posted on the blog were also performed by one researcher (first author) with consultation with a second researcher (principal investigator) underpinning by a content analysis approach(Reference Elo and Kyngäs42) using the NVivo 10 software (NVivo qualitative data analysis Software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2012). The researcher first became immersed with the data by reading the transcripts of mothers’ comments several times to gain an overall understanding of mothers’ narratives. At this stage, it was found that mothers commented on the blog in a manner that did not correspond to the sequence of questions that the RD-blogger asked at the end of every post (Table 1). Meetings with a second researcher (principal investigator) were held to discuss the data and it was deemed appropriate to use a mixed inductive (i.e. allowing the categories and names of categories to flow from the data) and directed (i.e. beginning coding with predetermined initial coding categories) content analysis approach(Reference Hsieh and Shannon43) to discover patterns, categories and themes in the data while concurrently being sensitive to the study context. Lists of categories that were grouped under higher order headings were created by collapsing categories that are similar or dissimilar into broader ones. Finally, each category was revised to identify overarching themes (i.e. reoccurring topics or meanings that represent the mothers’ comments) to inform the creation of a comprehensive interpretation of findings. A second researcher (principal investigator) reviewed the list of themes and the final categories were generated by consensus. In general, mothers wrote clear and brief comments, making the data easy to interpret. Furthermore, since critical discussions took place between researchers at all stages of the analytic process without major disagreements on coding arising, it was judged that inter-rater reliability testing was not necessary. The outcomes of the analytic process presented in the present study are themes salient to the process evaluation research questions regarding the factors involved during the intervention that affected dietary behaviours and engagement with the blog. Comments posted by mothers on the blog that were not included as salient themes are briefly presented in the result section below. Themes are not mutually exclusive. Mothers’ comments may be included in multiple subthemes.

Results

Study sample description

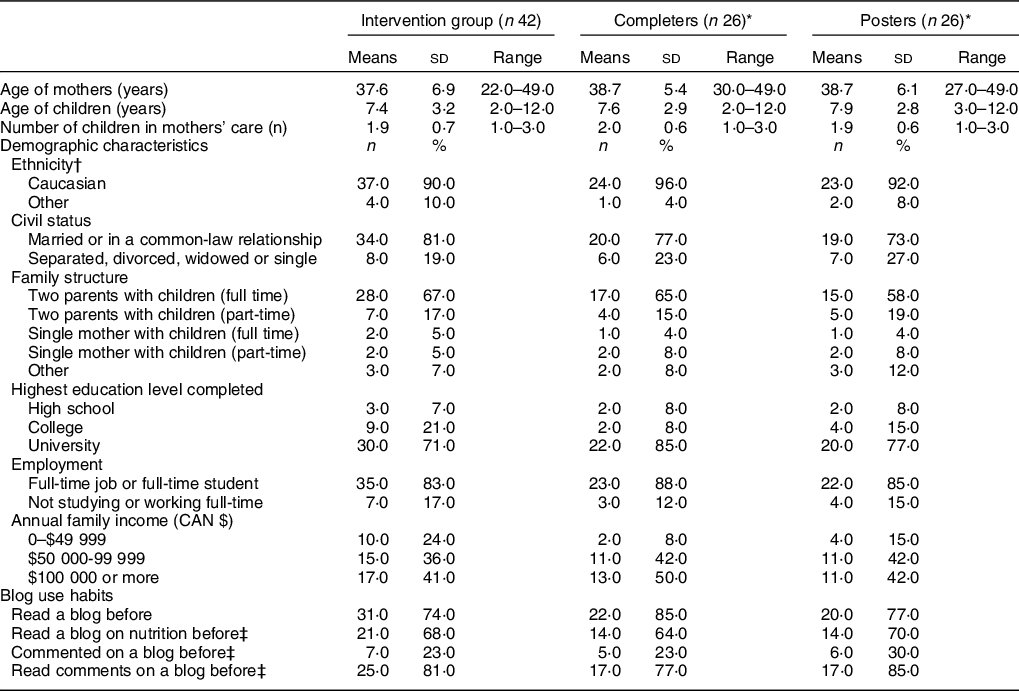

Table 2 presents the characteristics at baseline of mothers randomised to the intervention group, including the mothers who completed the post-intervention blog satisfaction questionnaire (completers), as well as the mothers who wrote at least one comment (posters) on the blog. Mothers were mostly Caucasian, lived with a partner and their children, had completed university studies, worked full-time and had an annual family income of 50 000 CAN$ or above. Prior to trial onset, most mothers were blog users, but few had the habit of commenting on blogs. Characteristics at baseline were equivalent between posters and non-posters (data not shown). Among completers, a greater proportion earned a family income of 50 000 CAN$ and above (P = 0·01) and had completed university studies (P = 0·02) compared with those who did not complete the post-intervention blog satisfaction questionnaire (non-completers). Completers were also more engaged with the blog as shown by a greater number of logins to the blog throughout the 6-month intervention (completers: mean ± sd, 34·5 ± 32·9 logins; non-completers: mean ± sd, 18·2 ± 8·2 logins; 95 % CI for mean difference (1·5, 31·2); P = 0·03)

Table 2 Characteristics at baseline of the intervention group (n 42), among which mothers completed the post-intervention blog satisfaction questionnaire (completers; n 26), and mothers posted comments on the blog during the 6-month intervention period (posters; n 26)

* Among the posters, four mothers withdrew from the study prior to the end of the 6-month intervention and, thus, did not complete the post-intervention blog satisfaction questionnaire, and one mother completed the intervention but had missing values for the satisfaction questionnaire. Among completers, five mothers did not post any comment on the blog during the intervention period.

† n 41 in the total intervention sample and n 25 in the completer and poster groups, respectively, due to one missing value for ethnicity.

‡ Only among those who have read a blog before (n 22 in the completer group and n 20 in the poster group).

Overview of mother-initiated comments on the blog

A total of 213 comments written by twenty-six mothers (of the forty-two mothers randomised to the intervention group) on the blog during the intervention (mean of eight mother-initiated comments/post; range = 1·0–16·0). As previously mentioned, mothers commented on the blog in a manner that did not correspond to the sequence of questions that the RD-blogger asked at the end of every post (Table 1). Specifically, mothers’ comments were directed to the RD-blogger as a response to the topics of blog posts (e.g. mothers shared their inspiration sources for recipes (n 38)) and the recipes that the RD-blogger featured each week on the blog (n 48 comments thanked the RD-blogger for the recipes, n 14 comments included a suggestion of ingredient modifications to a recipe and n 9 comments included technical questions regarding a recipe). The blog was also used by mothers to ask various questions to the RD-blogger regarding milk and alternatives (n 11), vegetables and fruits (n 5), dietary fats (n 2), weight management (n 2) and resources for healthy recipes (n 1). Few comments were posted by mothers in reaction to a comment posted by one of their peers. Those ‘mother–mother discussions’ aimed to thank mothers who had shared a personal recipe (n 27 comments included a personal recipe) or strategies to adopt a healthier diet (n 12), to ask for help or seek advice (n 2) and to share a personal strategy in response to a difficulty expressed by a fellow mother to preserve the freshness of pre-washed vegetables (n 1).

Participants’ perceptions of the blog’s usefulness to improve dietary habits

Twenty of the 26 (76·9 %) mothers who completed the post-intervention blog satisfaction questionnaire (among which five mothers did not post any comment on the blog) reported that the blog had been helpful to improve their dietary habits. Sixteen mothers (61·5 %) agreed or strongly agreed that the blog helped them improve their food skills such as planning family meals and buying fresh vegetables and fruits. Others were neutral (n 8, 30·8 %) or in disagreement (n 2, 7·7 %) with this affirmation. Similarly, qualitative findings from the content analysis of mother-initiated comments on the blog revealed that five mothers reported that the intervention had promoted positive changes in some aspects of their eating habits. Those positive changes were better reliance on internal hunger and satiety cues, increased knowledge to ways to include more milk and alternatives in recipes, willingness to ask more frequently for their children’s help for preparing meals and new habits of planning family meals.

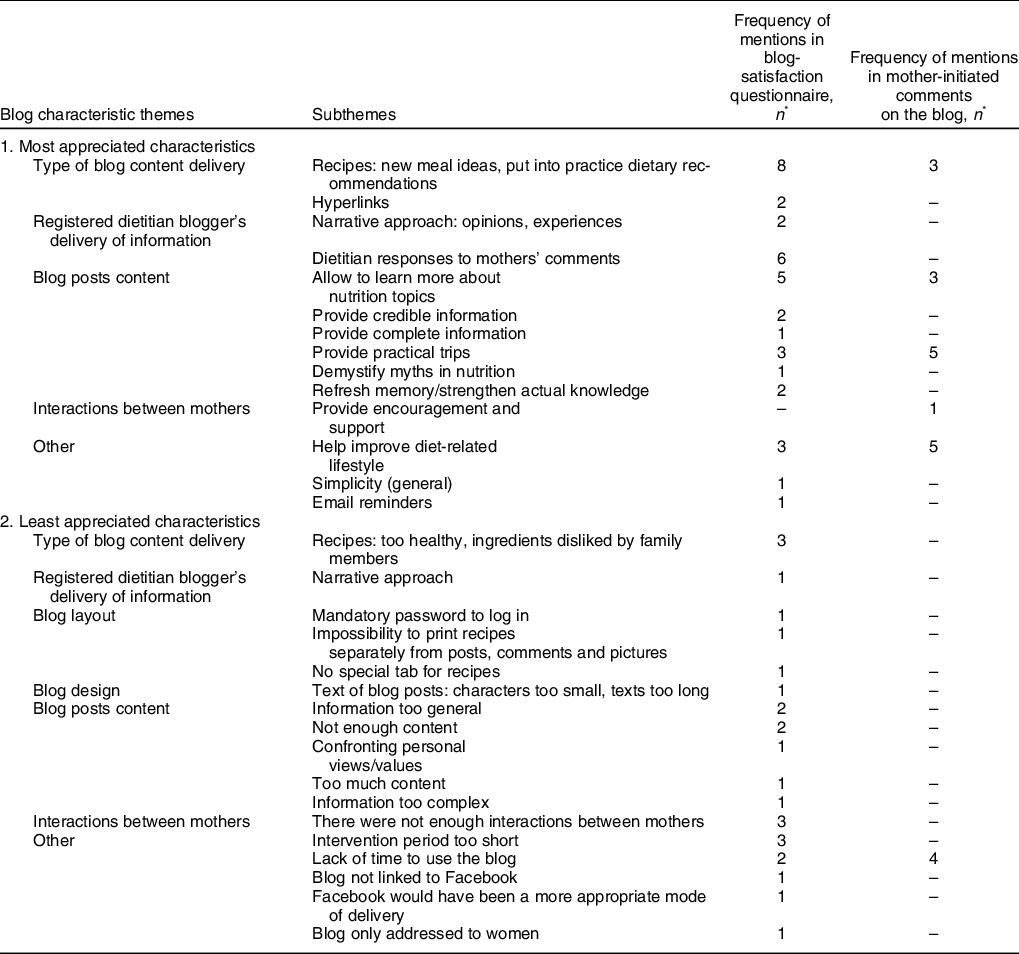

Participants most and least appreciated blog characteristics

Table 3 presents the themes associated with the most and least appreciated blog characteristics as reported by mothers in the blog satisfaction questionnaire and in their comments posted on the blog. Themes are further described in the subsequent sections with supporting quotations.

Table 3 Themes and subthemes associated with mothers’ most and least appreciated blog characteristics identified in open-ended questions from the blog satisfaction questionnaire and in mother-initiated comments on the blog

* Total number of times that a theme was identified in mothers’ responses to the open-ended questions from the blog satisfaction questionnaire and in mother-initiated comments on the blog.

The most useful blog characteristics were the nutritional information shared by the RD-blogger (n 15/26 mothers; 57·7 %) and the recipes published on the blog (n 7/26 mothers; 26·9 %). The recipes inspired new meal ideas. Recipes were also considered useful to put into practice the dietary recommendations of the RD-blogger. The possibility to ask questions to the RD-blogger and her prompt reply to mothers’ comments were also frequently praised. In particular, mothers mentioned that the interaction with the RD-blogger was easy. Mothers also appreciated her summary of the interactions in the comment section of the blog in the subsequent postings. Mothers generally liked the content of blog posts, which provided ‘complete and up-to-date evidence-based nutrition knowledge’ (Participant #56) and practical tips to improve diet-related lifestyles such as the planning and preparation of family meals. The content of blog posts was also perceived as a resourceful source of information on healthy eating and a useful tool to strengthen current nutrition knowledge. Email reminders when new posts were published were also appreciated.

Among the least appreciated blog characteristics, one mother mentioned that an average of one recipe published on the blog every week was insufficient. Two mothers disliked the selection of recipes, declaring that they were ‘too healthy’ (Participant #76) or that ‘several [recipes] seemed complex to prepare and less accessible, and, unfortunately, featured ingredients that I disliked or that were disliked by members of my family’ (Participant #35). There were mixed reactions to the narrative tone used by the RD-blogger (i.e. she wrote her posts in the first person and related personal experiences involving food): it was appreciated by some mothers – described as ‘dynamic, sympathetic as well as professional’ (Participant #46) – whereas it was disliked by one mother. Some mothers were disappointed that there were limited interactions between the participants in the comments section of the blog during the intervention. For example, one mother said, ‘I think the more interaction there is [in the comments section of the blog], the more interesting and insightful the blog would become’ (Participant #47). Similarly, qualitative findings from the content analysis of mother-initiated comments on the blog revealed that some mothers were grateful for the encouragement and support from fellow mothers during their process of adopting a healthier diet. Blog post content was perceived by some mothers as too complex. On the other hand, others mentioned that blog posts did not provide enough new nutrition information. One mother mentioned she would have preferred that blog posts be linked to Facebook. Similarly, another participant mentioned that she would have preferred a private Facebook group to deliver the intervention. One mother did not appreciate the mandatory identification code and password to log on to the intervention blog. She explained that this step prevented her from using the blog. Four mothers believed that a 6-month dietary intervention was too short. They explained that they lacked time to read the blog content or that they perceived that 6 months was too short a period to integrate the recently acquired dietary habits. Similarly, qualitative findings from the content analysis of mother-initiated comments on the blog revealed that lack of time was a barrier to engaging with the blog for four mothers. Among them, one mother regretted not being able to engage more with the blog:

‘At the beginning [of the intervention], I followed the blog religiously, but these past two weeks have been crazy… I was eager to come back!’ (Participant #26).

Finally, one mother commented that because the blog was addressed to mothers,

‘it contributed to the belief that women are responsible to household food-related tasks’ (Participant #46).

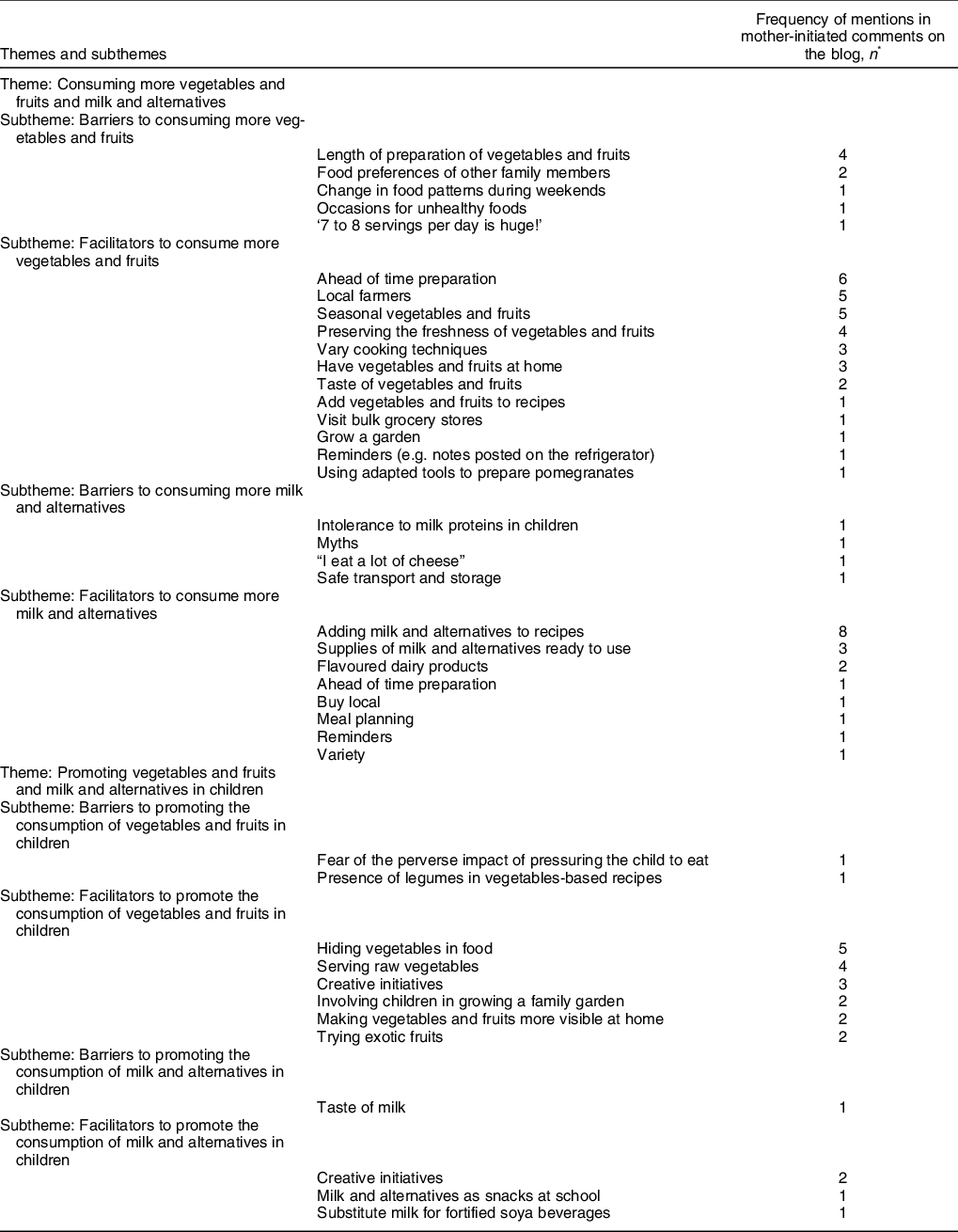

Barriers and facilitators affecting dietary behaviour change

Qualitative findings from the content analysis of mother-initiated comments on the blog allowed a deeper understanding of mothers’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to their adoption of a healthier diet that included more vegetables and fruits and milk and alternatives and to the promotion of those foods to their children. Key themes and subthemes are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4 Barriers and facilitators mentioned by mothers with regard to the adoption of a healthy diet including vegetables and fruits and milk and alternatives and the promotion of those foods to their preschool- and school-age children identified in mother-initiated comments on the blog

* Total number of times that a subtheme was identified in mothers’ comments on the blog.

Mothers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to consuming more vegetables and fruits

Mothers reported few barriers to consuming more vegetables and fruits every day. The length of preparation of vegetables and fruits was the barrier most frequently discussed. Four mothers invoked a lack of motivation to include more vegetables and fruits in their diet because it took too long to prepare.

‘I must admit that beets throw me off because of the necessity to peel off their skin. Do you think I could use a pressure cooker to shorten the process? […]’ (Participant #79).

Other referred to the food preferences of other members in the household – most importantly of their children – and having more difficulties including vegetables and fruits in the family diet when vegetables and fruits on sale are not favourites at home or on weekends. One mother mentioned that the number of servings per day of vegetables and fruits recommended for adult women in the Canadian dietary guidelines in force when the study was initiated (i.e. seven to eight servings/day) was a goal difficult to reach. This mother also specified that including vegetables and fruits in recipes such as smoothies, snacks and soups helped make this goal achievable. During the intervention, thirteen mention of adjustments made to recipes to make them healthier by adding vegetables and fruits were shared by mothers on the blog.

Overall, mothers mentioned a greater variety of facilitators than barriers to increase their consumption of vegetables and fruits. Ahead of time preparation of vegetables and fruits – such as washing, cutting and portioning vegetables after purchasing them – was a strategy mentioned by five mothers to save time during meal preparation on weekdays. Among those, three mothers also stated that having vegetables and fruits available at hand was a key strategy to eat more vegetables and fruits.

‘[…] when I buy green beans for example, I buy a lot, I cook them and then freeze them. It is very convenient to always have a handful of vegetables available, that are already cooked and ready to be used in recipes.’ (Participant #85).

The short shelf life of vegetables and fruits was a challenge discussed by four mothers. To cope with this barrier, mothers stored vegetables and fruits in containers specifically designed to keep them fresh or purchased only the amount of vegetables and fruits that would be consumed by their family during the week. The availability of vegetables and fruits rhymed for some mothers with seasonal products. Four mothers reported buying vegetables and fruits from local farmers and one mother mentioning growing a garden in the summer helped her eat more vegetables than usual.

‘This year, I grew a vegetable garden. It was a quite a time-consuming project, since I started from seeds. However, I undeniably ate more vegetables than usual […].’ (Participant #34).

Mothers also mentioned using reminders (e.g. notes posted on the refrigerator) to help them include vegetables and fruits in lunch boxes and family meals, visiting bulk grocery stores where they could discover new vegetables and fruits (e.g. exotic fruits and uncommon dried fruits), varying cooking techniques and using adapted tools to make preparation of pomegranates easier and fun. Two mothers reported adding vegetables to the recipes to change the taste of a dish. This strategy was particularly convenient with children considered fussy eaters.

‘[…] I used vegetables to change the taste of meals: I chopped them finely in a food processor before adding them to recipes, such as ham pot pies; I could then use all the vegetables that I wanted without having the kids noticing that they were eating them. A great trick for fussy eaters!’ (Participant #81).

Mothers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to consuming more milk and alternatives

Four mothers shared comments on the blog regarding barriers to increase their consumption of milk and alternatives. Dairy products need to be refrigerated for safe transportation and storage. This was perceived by one mother as a challenge to include more milk, cheese and yogurt in her lunches for work. Beliefs of negative impacts of soya-based products on puberty in young girls prevented one mother from buying fortified soya beverages. Intolerance to milk proteins and soya in her child prompted one mother to use caution with milk and alternatives at home. With time, this participant had stopped buying and consuming those foods herself. Last, one mother commented that: ‘Personally, my challenge would rather be to eat smaller portion sizes of dairy products, because I eat a lot of cheese.’ (Participant #26). This statement reflects difficulties to include a greater variety of dairy products and non-dairy substitutes in her diet.

Facilitators to consuming more milk and alternatives every day reported by mothers included reminders, ahead of time preparation (e.g. portioning cheese and yogurt when returning from the grocery store), buying local dairy products, keeping supplies of milk and alternatives ready to include in recipes or in lunch boxes and adding dairy products to recipes. Meal planning and varying the snacks served to their family (e.g. yogurt and cheese) were also perceived as useful by one mother. One mother mentioned in two of her comments liking the flavours of aromatised commercial dairy products (e.g. yogurt and kefir) which were convenient to increase the number of dairy products that she consumed.

‘[…] I have tried kefir in the past and did not like it then. However, strawberry, vanilla, or other fruit-flavoured kefir products are delicious to drink, to add to smoothies, or to substitute cow milk with cereals.’ (Participant #74)

Mothers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to promoting the consumption of vegetables and fruits in their children

Two mothers discussed barriers to promoting a higher consumption of vegetables and fruits in their children. The first referred to the presence of legumes – a food disliked by their child – in vegetable-based recipes such as chili or soup that resulted in children’s refusal to eat the meal. The second mentioned she did not encourage her child to eat more vegetables and fruits by fear of creating an unhealthy relationship with food.

Several facilitators were discussed by mothers to help increase their children’s consumption of vegetables and fruits. Mentioned by four mothers, the most common strategy was to hide vegetables among other appreciated foods such as meat and cheese-based recipes and spaghetti sauce. Three mothers mentioned that their children liked vegetables better when they were served raw instead of cooked. Three mothers used creative activities to promote the consumption of vegetables in their children, such as cooking soups of different colours and giving them fun names (e.g. Shrek’s soup made of broccoli or asparagus), decorating home-made pizza with vegetables to create shapes and figures and serving vegetables and fruits to children in containers decorated with stickers. Two mothers mentioned that accessibility and visibility of vegetables and fruits at home were important.

‘Regarding fruits, we have adopted a beautiful serving dish display on the kitchen counter. I never saw apples vanish this fast! What if I use the same strategy with vegetables?’ (Participant #6)

Two mothers commented that including their child in the process of growing and cultivating a family garden had increased their child’s acceptance to try new vegetables. The last discussed facilitators related to exotic fruits and how engaging children in the choice of buying fruits they have never tried (e.g. carambola, papaya and mango) had increased their openness to discovery and the variety of fruits that they consumed.

Mothers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to promoting the consumption of milk and alternatives in their children

The only barrier to promoting the consumption of milk and alternatives in children, mentioned by one mother, was related to the taste of milk: ‘In light of your [RD-blogger] answer regarding fortified soy beverages, I think this could be a great option for lunch boxes, especially when cow milk is refused by the child (when it is not extremely cold, it is not as good, apparently) […].’ (Participant #47). Eating dairy products as snacks at school (e.g. in the form of dip for vegetables) was discussed by one mother as a strategy to promote milk and alternatives in her children. Two other mothers shared creative initiatives as facilitators such as serving milk in a bottle with a straw and cheese in containers decorated with stickers.

Discussion

Principal findings

Findings from this mixed-methods process evaluation study provided insights into the acceptability of a healthy eating blog, used as a stand-alone knowledge translation strategy, to promote healthy eating in French-speaking mothers living in Quebec City, Canada, and their 2–12-year-old children. Findings from this process evaluation also revealed engagement challenges and barriers that could have affected intervention mechanisms. These are important findings to better understand the short-term (Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe28) and long-term(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe29) quantitative impact of the blog. First, both quantitative findings from the post-intervention blog satisfaction questionnaire and findings from the qualitative content analysis of mothers’ comments on the blog suggest that the blog was perceived as an acceptable and useful tool to deliver a dietary intervention. However, findings also highlighted the complexity for intervention developers and behavioural researchers to design a blog that will respond to the needs of all users. Indeed, although several characteristics of the blog were highly appreciated by the participants (e.g. the nutritional information and the recipes shared by the RD-blogger), there were mixed reactions for other aspects of the blog (e.g. the content of blog posts and the duration of the intervention). Those aspects of the blog that were least appreciated by mothers are areas of possible improvements for the development of future similar studies. Second, meal planning and preparation skills were identified as important assets to improve the consumption of vegetables and fruit and milk and alternatives in mothers and their children. Findings also showed that time constraints strongly influenced mothers’ perceived abilities and motivation to adopt a healthier diet. Time constraints also negatively impacted mothers’ engagement with the blog. The following paragraphs provide an in-depth discussion of the main findings and recommendations for dietetic practice and future research.

Despite the absence of evidence of differences in dietary outcomes between mothers exposed to the blog and those randomised to the controlled group (Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe28,Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe29) , most mothers who completed the study (posters of comments and well as completers of the satisfaction questionnaire) perceived the blog useful to improve their dietary habits. Among the most appreciated blog characteristics, mothers mentioned the credible and practical nutrition information and tips shared by the RD-blogger. Although mothers globally found the RD-blogger helpful, it is possible that the strategy-oriented environment created by the RD-blogger (e.g. numerous solutions and strategies were suggested by the RD-blogger in the blog posts to overcome barriers to healthy eating) has influenced mothers to view healthy eating behaviour change in a positive way. This, in turn, may have promoted mothers to share more strategies and facilitating factors than barriers to improve their eating habits in the comments they posted on the blog. Moreover, it is not clear how much trial results depended on the RD-blogger delivery of information and facilitating style, or whether other components of the blog provided greater influence for mothers. For instance, the weekly healthy recipes featured in the blog, as well as healthy recipes in general, were themes discussed at length by mothers in their comments posted on the blog. It is possible that mothers’ high interest in the healthy recipe suggestions prevailed on their willingness to respond to the specific questions that the RD-blogger asked at the end of every post. Additionally, the recipes appeared to have satisfied mothers’ needs for practical ways to put healthy eating recommendations into practice. Some mothers mentioned feeling more empowered and more knowledgeable about ways to make positive changes in their dietary habits. Mothers reported better recognition of satiety cues (which could, however, rather be attributed to the question-behaviour effect(Reference Sprott, Spangenberg and Block44)), increased knowledge on ways to adopt a healthier diet and more frequent involvement of children in meal preparation. In concordance with previous qualitative studies conducted among mothers (Reference Peters, Parletta and Lynch10,Reference Sonneville, La Pelle and Taveras45) , mothers in the present study believed that involving children in household food activities (i.e. growing and shopping for food, planning and cooking meals) facilitated the consumption of healthy foods in their children. Evidence from experimental studies has shown that children (5–7 years old) eat more foods that they prepared themselves compared with the food being served to them, including vegetables(Reference DeJesus, Gelman and Herold46), and that involvement in cooking increased spontaneous choices of children (7–11 years old) towards unfamiliar foods containing vegetables(Reference Allirot, da Quinta and Chokupermal47).

Overall, facilitating factors for mothers to increase their consumption of vegetables and fruit and milk and alternatives related mainly to the knowledge and skills required for planning and preparing healthy meals. These findings complement cross-sectional evidence showing positive associations between cooking skills and dietary outcomes in adult populations, such as increased vegetable liking and home availability of vegetables(Reference Overcash, Ritter and Mann48), greater vegetables and fruit intakes (Reference Hartmann, Dohle and Siegrist5,Reference McLaughlin, Tarasuk and Kreiger49) and lower convenience food or ready-meal consumption frequency (Reference Hartmann, Dohle and Siegrist5,Reference van der Horst, Brunner and Siegrist50) . These findings also relate to those of an randomised controlled trial which has recently shown that a questionnaire-based implementation intention intervention presenting a list of similar solutions to overcome barriers to vegetables and fruit intake was effective in promoting an increase consumption of one serving per day of vegetables and fruits in childbearing age women at risk for gestational diabetes mellitus at 6 months post-intervention compared with baseline(Reference Vezina-Im, Perron and Lemieux51). In the healthy eating blog study, mothers exposed to the blog increased their consumption of vegetables and fruits by 1·2 serving per day, but differences in dietary intake between groups over time did not reach statistical significance(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe28). These null findings may be attributed to insufficient statistical power consequent to recruitment difficulties or a ceiling effect as described elsewhere (Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe28,Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe31) . Although a great variety of facilitators (e.g. meal planning, making vegetables available in the home and integrating dairy products into recipes) were identified in mothers-initiated comments to increase their consumption of vegetables and fruit and milk and alternatives, it remains unclear if those strategies were adopted by mothers in response to the intervention or if they were already used prior to trial onset. It is also possible that the few barriers that were identified in the content analysis of mothers-initiated comments on the blog that could have hindered mothers’ abilities and motivation to adopt positive dietary behaviour change (e.g. lack of time, children’s food preferences and food allergies) may have weighted particularly heavily in mothers’ decisional balance or capability to behaviour change. Recent studies have demonstrated how making decisions for children affects the food choices of adults(Reference Akkoc and Fisher52) and how more convenience food solutions – at the expense of nutritional quality – are used by parents at dinnertime when confronted with time pressure and stress coming from work and/or family commitments(Reference Alm and Olsen53).

Time constraints were a barrier to engaging with the blog more often. Evidence has shown that Web-based health interventions were perceived by women as easier to integrate into their everyday lives than face-to-face interventions due to the flexibility and 24-h availability of online content(Reference Verhoeks, Teunissen and van der Stelt-Steenbergen54). However, it is possible that this flexibility, potentially enhanced by the absence of face-to-face contact with the RD, led to reduced perceived obligation and lower motivation to engage with the blog when confronted with demanding life responsibilities. Lack of personal relevance was another potential barrier to engagement. For example, some mothers mentioned that the content of the blog was either too simple or too complex for their level of nutrition knowledge. This highlights the complexity of designing a ‘one-size fits all’ blog to deliver a dietary intervention. Regarding the acceptability of the intervention dose of exposure, a period of 6 months with weekly blog postings was considered too short by some mothers to integrate newly acquired dietary habits. Thus, it could be hypothesised that the intervention period was also too short to produce dietary behaviour changes. Again, this finding relates to the time constraints experienced by some mothers who would have appreciated a longer intervention period to read the blog and interact with its components later on, at their own pace. Some mothers suggested the use of the social media platform Facebook would have been more convenient. Using Facebook as a mode of delivery may help overcome time constraints expressed by mothers to engage with the blog more often, because it is already part of the daily social media routines of most participants in the present study(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe28) and of mothers in general(Reference Duggan, Lenhart and Lampe55). The acceptability of Facebook-delivered peer-group health promotion interventions has been demonstrated in mothers of infants (Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard16,Reference Gruver, Bishop-Gilyard and Lieberman17,Reference Waring, Moore Simas and Oleski56) , but has yet to be evaluated among mothers of preschool and school-age children.

A considerable proportion (40 %) of mothers were passive observers (i.e. they logged on to the blog but did not write comments themselves). Similar findings have been observed in other social media-based peer-support interventions in mothers of young children (Reference Waring, Moore Simas and Oleski56,Reference Niela-Vilen, Axelin and Melender57) . Although the setting of the research was designed to replicate naturalistic interactions found in healthy eating blogs, it may have influenced mothers’ willingness to openly convey their viewpoints in the comments section of the blog. Although few peer-to-peer active discussions took place on the blog, the peer support received during the intervention was valued. Commenting was possible at any time of the day regardless of mothers’ geographical distances during the intervention period. This suggests that the blog-delivered intervention was successful in meeting some mothers’ desire to make contact with fellow mothers with whom they could share common experiences (Reference McDaniel, Coyne and Holmes58,Reference Pettigrew, Archer and Harrigan59) such as discussing challenges associated with healthy behaviour changes and child feeding difficulties(Reference Mitchell, Farrow and Haycraft60). Moreover, since parents’ use of social media and perceived levels of support are highly related(Reference Haslam, Tee and Baker61), mothers who believed that the online support they received from fellow mothers was helpful, may have been more motivated to maintain an active engagement with the blog throughout the intervention to seek and receive online support.

Implications for future research and for the dietetic practice

Findings from the present process evaluation study can help inform dietetic practice and the development of future studies using social media, like blogs, to deliver a healthy eating intervention. First, research on the effects of social media in dietetic practice has mostly evaluated multi-component interventions (i.e. including various modes of delivery such as social media, emails, websites and text messaging, in various combinations)(Reference Dumas, Lapointe and Desroches62). Some mothers suggested the use of Facebook as a preferred strategy to deliver the intervention content. Thus, future studies should conduct preliminary qualitative needs assessment (e.g. using interviews or focus groups) with mothers of preschool and school-age children to adequately integrate other social media platforms to be used in complementarity with the blog. For instance, a private Facebook group could be used as a tool to facilitate social interactions and discussion with the RD-blogger and fellow mothers (Reference Hammersley, Okely and Batterham15,Reference Fiks, Gruver and Bishop-Gilyard63) . Facebook could also be used to notify study participants for new blog postings. Second, future social media-delivered healthy eating dietary interventions should emphasise on the acquisition of food literacy competences. Meal planning and preparation skills were facilitating factors for mothers to consume more vegetables and fruits and milk and alternatives. Findings from the impact evaluation of the healthy eating blog trial showed that mothers who reported feeling competent and enjoying planning family meals had higher odds of consuming at least five servings per day of vegetables and fruit and at least two servings per day of milk and alternatives 6 months after the end of the intervention(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe29). Suggestions of healthy recipes should be part of the content of healthy eating blogs (or other social media platforms) written by RD. Recipes represent tangible means for the public to implement healthy eating recommendations. Third, more research (e.g. mediation analysis) is needed to better understand the relationships between engagement and digital behaviour change intervention effectiveness. We have previously demonstrated that each login on the blog predicted small increases in vegetables and fruit intakes of mothers 3 months after the start of the intervention, but this association was not observed in the long term(Reference Dumas, Lemieux and Lapointe28). Future qualitative research would help increase our understanding of the impact of various types of online behaviours (e.g. lurking v. posting comments on the blog) and how to promote effective engagement in social media-delivered interventions conducted with mothers of young children. Last, future similar studies could include both parents as agents of change to promote healthy eating in children. Evidence is growing on the influence of fathers on their children’s eating habits and behaviours(Reference Rahill, Kennedy and Kearney64). The inclusion of fathers could help reduce the burden of time for mothers facing high work and family responsibilities. The content of the intervention, the social media platform(s) to use and how responsibilities between partners for their implication in the study should be shared are examples of elements that should be planned in partnership with both fathers and mothers in future family-based social media-delivered interventions.

Strengths and limitations

Some limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. First, as the current study focused on a process evaluation in the context of an randomised controlled trial, the findings are only generalisable to the specific group of mothers randomised to the intervention. The sample of the current study was composed of a small group of highly educated, mostly Caucasian mothers with a high socio-economic status and with an overall interest in healthy eating. Those mothers may have exhibited more ‘desirable’ eating behaviours and practises. A socio-economic gradient has been identified for vegetables and fruit consumption, where individuals with higher socio-economic status and with higher education levels purchase and consume more vegetables and fruit than those with lower income and lower education levels (Reference Azagba and Sharaf65–Reference Ricciuto, Tarasuk and Yatchew68). Another limitation of the current study is that the qualitative findings mostly capture the perspectives of mothers who completed the 6-month intervention. Qualitative individual interviews or focus groups with a purposeful sample of high and low engaged study participants would have provided a more comprehensive picture of the acceptability, perceived usefulness of the intervention blog to help them improve their dietary habits and how the intervention design could be improved to better respond to mothers’ needs and realities (e.g. work-family balance). Those mothers logged on to the blog more often and posted more comments on the blog and, thus, the perspectives of the mothers who stopped using the blog and who were lost to follow-up over time with respect to the identified themes may differ. Last, mothers of preschool-age children (2–5 years old) and those of school-age children (6–12 years old) may have different perceptions regarding healthy eating, including the promotion of vegetables and fruits intake among children(Reference Nepper and Chai12), but this comparison was beyond the scope of our study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings from the current study complemented the quantitative findings of the randomised controlled trial by suggesting that healthy eating blogs written by an RD may be an acceptable format of intervention delivery among mothers, with the most appreciated blog characteristics being the nutritional information provided by the RD-blogger, healthy recipes and interactions with fellow participants and the RD. However, many barriers to healthy eating remain, such as the extent to which participants engage in the dietary intervention, and time constraints inherent to their busy work and family schedules.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express their gratitude to all mothers who dedicated time to participate in the study. Financial support: This work was supported by the Danone Institute (grant number 107 217) which had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of this article and in the decision to submit the article for publication. A-A.D. is supported by a fellowship award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MFE-164705). Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: A-A.D. contributed to the acquisition of data and was in charge of the analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript; A.L. coordinated the acquisition of data; J.R., S.L. and V.P. contributed to the conception and design of the study as well as to the interpretation of data and S.D. was in charge of the conception and design of the study and had primary responsibility for the final content. All the authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Université Laval Ethics Committee (project no 2014-257 A-5 / 12-07-2016). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.