Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is a genetic disorder characterized by high LDL-cholesterol level and a higher risk of premature atherosclerotic CVD( Reference Goldstein, Hobbs and Brown 1 ). FH is caused by mutations in the LDL receptor gene (LDLR) and, less frequently, in the apolipoprotein B gene (APOB). Although FH highly increases cardiovascular risk, atherosclerotic CVD prevalence varies substantially by cohort and country, even across cases with the same genetic mutation( Reference Alonso, Mata and Castillo 2 – Reference Slimane, Lestavel and Sun 4 ). These findings suggest that environmental, metabolic and genetic factors could explain the differences in the CVD burden of these patients( Reference Jansen, van Wissen and Defesche 5 ). In fact, a recent study of the SAFEHEART study (Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolemia Cohort Study) identified BMI increase, tobacco consumption and hypertension as predictive risk factors for the development of CVD in FH patients( Reference Pérez de Isla, Alonso and Mata 6 ).

At the population level, diet is one of the most important environmental factors affecting LDL-cholesterol level as well as other CVD risk factors( Reference Estruch, Ros and Salas-Salvadó 7 – Reference Dehghan, Mente and Zhang 9 ). Nevertheless, dietary studies on FH-affected populations are scarce. Studies in children with FH in Norway showed that a dietary protocol focused on reducing saturated fat consumption did impact patients’ lipid profiles favourably( Reference Tonstad, Leren and Sivertsen 10 , Reference Torvik, Narverud and Ottestad 11 ). Although most patients with FH will require lipid-lowering therapy for life( Reference Mata, Alonso and Ruiz 12 – Reference Saltijeral, Pérez de Isla and Alonso 14 ), main clinical guidelines also include a series of dietary and nutritional recommendations as part of treatment( Reference Mata, Alonso and Ruiz 12 , Reference Watts, Gidding and Wierzbicki 15 , Reference Nordestgaard, Chapman and Humphries 16 ).

The main objective of the present study was to describe the lifestyle habits, especially diet-related, the degree of adherence to a Mediterranean-type diet and the relationship with CVD among individuals aged ≥18 years with FH and their relatives registered at the SAFEHEART cohort( Reference Mata, Alonso and Badimón 17 ).

Methods

Study design and participants

Data came from the SAFEHEART study, the design and methodology of which have been previously described( Reference Mata, Alonso and Badimón 17 ). Briefly, SAFEHEART is a prospective, multicentre, nationwide study of a cohort of individuals in Spain with molecular diagnosis of FH and their non-FH affected family members. From January 2004 to January 2016, the study enrolled 4217 participants from 829 families. The local ethics committee of the University Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz (Madrid) approved the study and all participants signed informed consents.

Exclusion criteria included: individuals under 18 years of age (n 269); failure to complete a semi-quantitative validated FFQ at inclusion (n 230); and reporting either an excessively high (>14 644 kJ/d (>3500 kcal/d) for women and >17 573 kJ/d (>4200 kcal/d) for men) or an excessively low energy intake (<2092 kJ/d (<500 kcal/d) for women and <3347 kJ/d (<800 kcal/d) for men) to eliminate outliers( Reference Willett 18 ) (n 4). Thus, herein we analysed the data from the remaining 3714 individuals.

Upon entering the study, participants completed a 113-item FFQ, previously validated for this population( Reference Vázquez, Alonso and Garriga 19 ). The FFQ included questions about the consumption of each food during the previous year, specifying the size of the typical portion and consumption frequency (never before or number of times per year, per month, per week or per day). Based on the FFQ data, adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MD) was evaluated with the MEDAS( Reference Schröder, Fitó and Estruch 20 ) questionnaire, an instrument validated and developed to assess the degree of adherence to a traditional MD pattern in the general population( Reference Estruch, Martínez-González and Corella 21 ).

Study variables

A clinical history and ad hoc questionnaires collected participant demographic and clinical characteristics including age, history of CVD, common CVD risk factors (type 2 diabetes, hypertension, smoking) and level of physical activity. A physical examination included standardized measurement of weight (kg) and height (cm), BMI (kg/m2) and waist circumference (cm). Blood pressure was measured twice in the supine position using an Omron MX3 sphygmomanometer.

Energy and nutrient intakes were estimated using the Spanish official food composition tables( Reference Moreiras, Carbajal and Cabrera 22 ). Two indices were used to assess fat quality: (i) the energy contribution of the different types of fatty acids according to their degree of saturation, i.e. SFA, MUFA and PUFA; and (ii) the relationship among them, i.e. PUFA:SFA and (PUFA+MUFA):SFA.

Adherence to the MD was evaluated with the fourteen-item MEDAS( Reference Schröder, Fitó and Estruch 20 ), comprising two items on eating habits, eight items on the consumption frequency of traditional MD foods and four items to assess low consumption levels of non-recommended foods. Each item is scored 0 or 1 for a total score ranging from 0 to 14. A higher score indicates greater adherence to a MD. We defined( Reference Martínez-González, Fernández-Jarne and Serrano-Martínez 23 ) high adherence as a score ≥9 and moderate adherence as a score ≥7. The MEDAS score was calculated from the FFQ data. However, since the FFQ does not specify the amount of olive oil used just for sofrito (a sauce consisting of tomato, onion and garlic, slow-cooked with olive oil), we cannot know whether participants met or did not meet the fourteenth MEDAS objective of sofrito consumption ≥2/week. Therefore this item was excluded, and the total score was based on a maximum of 13 points. Physical activity was measured with the reduced version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)( Reference Rütten, Ziemainz and Schena 24 ).

Statistical analysis

We performed descriptive analyses with the objective of describing the dietary habits of the SAFEHEART cohort and comparing the regular diet of participants with and without FH. Variables were analysed separately by sex. Qualitative variables are described by number of cases and corresponding percentages; normally distributed quantitative variables are described by their means and sd; and non-normally distributed quantitative variables are described with the median and interquartile range. The χ 2 test, Student’s t test for independent data and the Mann–Whitney U test for independent data were used to compare differences across qualitative, normally distributed quantitative and non-normally distributed quantitative data, respectively. Statistical significance was set at two-sided P<0·05.

Results

Description of the sample

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the 3714 individuals, 2736 (73·6 %) had molecular confirmation of FH and 978 were non-affected family members (negative genetic study; control group). Over half (54 %) were women and the mean age was 45·1 (sd 15·6) years. The majority of patients were on lipid-lowering treatment at study entry. Mean BMI was 26·9 (sd 4·1) kg/m2 in men and 25·8 (sd 5·3) kg/m2 in women (P<0·005). Over one-third of the entire sample (36·7 %) was overweight and 20·2 % were obese. We did not find differences in BMI and prevalence of overweight or obesity between participants with and without FH. Prevalence of hypertension and type 2 diabetes was 14·7 and 4·0 %, respectively, without differences by FH status. More men than women were current smokers (32·1 and 24·8 %, respectively; P<0·005) and more controls than FH patients smoked (33·8 and 26·3 %, respectively; P<0·005). Patients with FH and a history of CVD reported the lowest rate of tobacco consumption (12·9 %).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of adults in the SAFEHEART study (Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolemia Cohort Study) by sex and diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH)

Values are mean and sd, median and interquartile range (IQR), or n and %.

Significant difference by diagnosis of FH: *P<0·05, **P<0·005.

† Statistical significance set at P<0·05.

‡ Defined as BMI=25·0–29·9 kg/m2.

§ Defined BMI≥30·0 kg/m2.

║ Family history of atherosclerotic CVD before age 60 years.

¶ Measured with the reduced version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)( Reference Rütten, Ziemainz and Schena 24 ).

A history of CVD was reported by 19·4 % of men with FH and 7·9 % without FH (P<0·005). Similarly, 8·1 and 2·1 % of women with and without FH had a history of CVD, respectively (P<0·005).

Physical activity

More women (62·3 %) reported moderate physical activity compared with men (51·6 %; P<0·005); further, women with FH were more likely to report moderate physical activity than those in the control group (P<0·005). Within the FH group, a higher proportion of patients who had already suffered CVD reported performing moderate physical activity than those with no CVD history (64·4 v. 58·4 %, respectively; P<0·05; data not shown).

Consumption of energy and nutrients

Table 2 shows the average consumption of macro- and micronutrients by sex and FH diagnosis. The mean daily energy intake was 8401 (sd 1966) kJ (2008 (sd 470) kcal), being higher in men and in non-FH individuals (P<0·005). Carbohydrates accounted for 43·0 % of energy, fats for 37·0 % and proteins for 18·1 %.

Table 2 Baseline nutrient intake of adults in the SAFEHEART study (Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolemia Cohort Study) by sex and diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH)

E%, percentage of energy.

Values are mean and sd, or median and interquartile range (IQR).

Energy intakes exceeding Willett’s limits have been excluded( Reference Willett 18 ).

Significant difference by diagnosis of FH: *P<0·05, **P<0·005.

† The dietary evaluation was carried out using a validated FFQ (113-item).

‡ Statistical significance set at P<0·05.

§ Na from food excluding salt.

In both sexes, the percentage of energy derived from complex carbohydrates and proteins was higher in patients with FH than the control group (P<0·005), whereas the percentage of energy derived from fats was higher in the control group (P<0·005). Table 3 shows the average consumption of macronutrients and fatty acids by CVD history and FH diagnosis. In both the FH group and the non-FH affected group, the percentage of energy from fats was higher in individuals without a history of CVD (P<0·005); the consumption of SFA followed a similar pattern (P<0·005).

Table 3 Baseline nutrient intake of adults in the SAFEHEART study (Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolemia Cohort Study) by previous atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) and diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH)

Values are mean and sd.

Energy intakes exceeding Willett’s limits have been excluded( Reference Willett 18 ).

† The dietary evaluation was carried out using a validated FFQ (113-item).

‡ Statistical significance set at P<0·05.

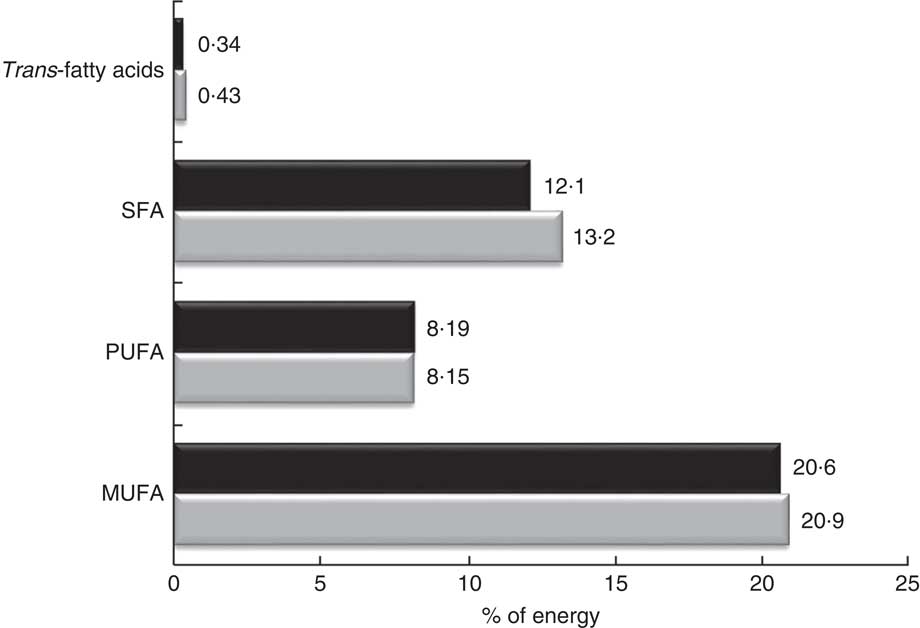

Regarding the quality of the fat consumed (Fig. 1), MUFA represented 20·7 %, SFA 12·4 % and PUFA 8·2 % of energy from fats. The intake of SFA was higher in the control group for both sexes (P<0·005), but no significant differences were detected in the energy derived from MUFA and PUFA between FH patients and controls. The percentage of energy from trans-fatty acids was low (0·3–0·4 %). The relationship between unsaturated and saturated fatty acids (PUFA:SFA and (PUFA+MUFA):SFA) was significantly higher in women (P<0·005) as well as in FH patients (P<0·005). The consumption of cholesterol was higher in non-FH affected participants (P<0·005). None of the groups reported a mean cholesterol intake exceeding 300 mg/d (nutritional objectives for the Spanish population( Reference Serra-Majem and Aranceta 25 )). The cohort’s overall consumption of n-3 fatty acids was 1·62 g/d with no substantial differences across groups.

Fig. 1 Percentage of energy from fatty acids in the SAFEHEART study (Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolemia Cohort Study) by diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH): ![]() , patients aged ≥18 years with a genetic diagnosis of FH (n 2736);

, patients aged ≥18 years with a genetic diagnosis of FH (n 2736);

![]() , non-affected relatives (n 978)

, non-affected relatives (n 978)

The mean consumption of total fibre was 31·1 (sd 8·3) g/d. When expressing this as an intake per 4184 kJ (1000 kcal), we detected a higher consumption in FH patients across sexes (P<0·005). The consumption of sugars was lower in FH patients compared with their non-affected relatives (P<0·05).

Food consumption

Table 4 shows the average food consumption by sex and FH diagnosis. Cereal consumption was significantly higher in men than women. However, there were no differences between FH patients and controls. Regarding the total consumption of milk products, there were no differences between participants with and without FH. However, more FH patients reported consuming skimmed milk products than non-FH participants (P<0·005).

Table 4 Baseline food and food group intakes of adults in the SAFEHEART study (Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolemia Cohort Study) by sex and diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH)

Values are median and interquartile range (IQR), or mean and sd.

Energy intakes exceeding Willett’s limits have been excluded( Reference Willett 18 ).

Significant difference by diagnosis of FH: *P<0·05, **P<0·005.

† The dietary evaluation was carried out using a validated FFQ (113-item).

‡ Statistical significance set at P<0·05.

Regarding the sources of animal protein, a higher consumption of red meats, sausages and processed meats was observed in the controls of both sexes than their FH-affected counterparts (P<0·005). The average total fish consumption was high (57 g/d) including that of blue fish; patients with FH reported a higher total fish intake than controls (67·1 and 60·4 g/d, respectively; P<0·005).

Regarding vegetables, participants reported an average consumption of 250 g/d, with patients’ intake being higher. In terms of fruit intake, the average amount reported was 272 g/d which is equivalent to about two medium pieces of fruit.

In terms of beverages, we detected a significantly higher consumption of sugary soft drinks in non-FH affected individuals regardless of sex than among FH patients (117·1 and 91·9 g/d, respectively; P<0·005). In the case of alcoholic beverages, both fermented and distilled, consumption was higher in men than in women (P<0·005).

Adherence to the Mediterranean diet

Based on the MEDAS( Reference Schröder, Fitó and Estruch 20 ) questionnaire, we observed that over 90 % of the individuals met the MD recommendation regarding the use of olive oil as the main culinary fat, as well as for a low consumption of animal fat. In addition, over half of the sample consumed more than 3 servings fish/week and consumed sugary soft drinks <1 time/d. However, fewer than 30 % of the participants reported the minimum daily recommended intake of vegetables and fruits.

The mean MEDAS score (out of 13 points) of the entire cohort was 6·14 points (95 % CI 6·1, 6·2), with higher means achieved by FH patients regardless of sex than controls (P<0·005). However, only 10·1 % of the total sample reported a high adherence to the MD pattern (score ≥9 points) and 31·8 % reported a moderate adherence (score ≥7 points), with women and FH patients scoring higher than their counterparts (Table 5).

Table 5 Score of Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS)( Reference Martínez-González, Fernández-Jarne and Serrano-Martínez 23 ) and degree of adherence to the Mediterranean diet of adults in the SAFEHEART study (Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolemia Cohort Study) by sex and diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH)

Values are mean and sd, or n and %.

Significant difference by diagnosis of FH: **P<0·005.

† Score range: 0–13. MEDAS 14th objective was excluded (sofrito consumption ≥2/week)

‡ Statistical significance set at P<0·05.

Given the lack of consensus regarding alcoholic beverages being recommended for cardiovascular prevention, the total score was recalculated after eliminating item 8 (wine consumption of ≥7 glasses/week). The new average score (now out of 12 points) was still significantly higher for FH patients than controls for both sexes.

Discussion

The present study shows that adults with FH have healthier dietary habits and a greater adherence to the MD compared with their non-FH relatives. They also smoke less, especially those individuals with history of CVD, and are more likely to be physically active. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first that analyses the nutritional characteristics, MD adherence and other lifestyles in a large population of adults with FH.

The relationships between diet, CVD and death are topics of major public health importance, and subjects of great controversy. In European and North American countries, the most enduring and consistent dietary advice is to restrict SFA, by replacing animal fats with vegetable oils( Reference Sacks, Lichtenstein and Wu 26 ). It has been shown in the PREDIMED study that a MD supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts is associated with a reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events and death in a high-risk primary prevention population in Spain, explained in part by the intake of MUFA and PUFA( Reference Estruch, Ros and Salas-Salvadó 7 ). One of the inclusion criteria in the PREDIMED study was an LDL-cholesterol level >160 mg/dl and therefore it is possible that some few cases of FH were included in the study; however, there are no specific results available regarding this population.

A key index of diet quality is the energy profile that was more balanced in patients with FH than in their non-FH relatives. Energy intake and BMI were significantly lower in FH patients. In addition, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in this population was slightly lower than in the Spanish general population (39·3 % of overweight and 21·6 % of obesity)( Reference Aranceta-Bartrina, Pérez-Rodrigo and Alberdi-Aresti 27 ).

Patients reported a lower energy intake from total and saturated fat due to a lower intake of whole milk, red meat, sausages and precooked foods. In the current study, fats accounted for 37 % of energy. The PURE study reported that total fat intake in quintile 5 (33·3–38·3 % of energy) was associated with a lower risk of total mortality and there was no association with CVD( Reference Dehghan, Mente and Zhang 9 ). Initial PURE study findings challenge conventional diet–disease tenets that are largely based on observational associations in European and North American populations, adding to the uncertainty about what constitutes a healthy diet( Reference Dehghan, Mente and Zhang 9 ).

It is well known that the quality of fat consumed affects the plasma lipid profile( Reference Mata, Ordovas and Lopez-Miranda 28 ) and other cardiovascular risk factors; thus, it is important to know the fatty acid distribution in this specific population with high cardiovascular risk. In the SAFEHEART cohort, the quality of fat reported reaches the recommended MUFA intake (≥20 % of energy) and in parameters like (PUFA+MUFA):SFA≥2 and PUFA:SFA≥0·5( Reference Serra-Majem and Aranceta 25 ). This is in part due to the high intake of olive oil, the main source of fat in the Mediterranean diet, and of n-3 fatty acids. The n-3 intake in this population was 1·62 g/d, explained by a higher consumption of fish compared with the Spanish general population( Reference Ruiz, Ávila and Valero 29 ).

Unfortunately, SFA intake was over 10 % of energy in patients with FH and in their relatives, even in those cases with CVD. This excess consumption of SFA is similar to that observed in the Spanish general population( Reference Ruiz, Ávila and Valero 29 , Reference Banegas, Graciani and Guallar-Castillón 30 ). On the other hand, cholesterol consumption in both FH and controls was below 300 mg/d, meeting the dietary recommendations( Reference Serra-Majem and Aranceta 25 ), in contrast to findings from the general population( Reference Banegas, Graciani and Guallar-Castillón 30 ).

Regarding carbohydrate intake, the PURE study showed that an intake over 60 % of energy was associated with an adverse impact on total and non-CVD mortality. In the SAFEHEART cohort, carbohydrates represented 43 % of total energy, a lower consumption compared with the 52·4 % reported in the PURE study for Europe and North America( Reference Dehghan, Mente and Zhang 9 ). Patients with FH reported a lower consumption of carbohydrates than non-FH relatives and similar to that found in the Spanish general population( Reference Ruiz, Ávila and Valero 29 ). This is mainly explained by fewer consumption of pastries and sugary soft drinks while eating vegetables, fruits and legumes in amounts close to dietary guidelines.

Overall, FH patients had a healthier dietary pattern than their non-FH relatives in terms of consumption of vegetables, fish, skimmed milk products, red meats, sausages and/or processed meats, butter and margarine. Patients with FH are more aware of cardiovascular risk and, therefore, more receptive to dietary and lifestyle advice. This is likely to be especially true regarding fat and cholesterol intake, lower energy consumption and greater energy expenditure. Further, based on our data, women seemed more likely to heed recommendations regarding physical activity.

A great advantage of using a validated adherence index to a dietary pattern is that it allows to evaluate the quality of the overall diet more than does each individual nutrient and/or food item. Among the many MD adherence indices, MEDAS is the only one validated in a high cardiovascular risk population( Reference Schröder, Fitó and Estruch 20 ). In our cohort, we found a greater adherence to the MD pattern in patients with FH compared with their non-FH relatives. The level of adherence was moderate (6·14 points) and similar to that described for the general population( Reference León-Muñoz, Guallar-Castillón and Graciani 31 ), with the difference that the score used in the current analysis was based in thirteen items v. the usual fourteen items used in other studies, making our score slightly better.

There are no other studies like the present one in other FH populations; therefore, we are very limited in terms of placing our work in the context of the existing literature. However, our results confirm previous data observed in a small group of children with FH reporting a healthier diet compared with non-FH children( Reference Molven, Retterstøl and Andersen 32 ). Regarding our control group (non-FH relatives), our results show that they also follow a healthier diet than the Spanish general population( Reference Ruiz, Ávila and Valero 29 , Reference Banegas, Graciani and Guallar-Castillón 30 ). One may speculate that having a relative with a genetic disorder that severely increases cardiovascular risk has a positive impact on one’s own dietary choices. Additionally, having a family history of CVD may increase awareness of cardiovascular risk in the family and diet-related risk factors for CVD. Although our population has a higher cardiovascular risk and most of them are under lipid-lowering therapy, the addition of a MD may improve or attenuate other classical CVD risk factors and biomarkers that increase cardiovascular risk( Reference Estruch, Ros and Salas-Salvadó 7 – Reference Dehghan, Mente and Zhang 9 , Reference Mata, Ordovas and Lopez-Miranda 28 , Reference Foscolou, Georgousopoulou and Magriplis 33 ).

Our results should be interpreted within the context of the study’s limitations. First, based on the cross-sectional nature of the study, we are unable to draw any conclusions regarding whether following a better diet would have a positive impact on the CVD burden of FH patients. Second, even validated questionnaires rely on self-reported data, which may be subject to recall error and social desirability bias. The present study also has several strengths. First, it is the largest population-based study of individuals with a molecular diagnosis of FH assessing nutritional intake with a comprehensive and validated dietary questionnaire. Second, individuals included in the SAFEHEART study are representative of FH patients residing in a Southern European Mediterranean country, a population that is severely understudied. Since the sample comes from the entire Spanish territory, the sample design reduces the selection bias. Third, individuals of the control group were part of the same families of patients with FH, so it can be argued that detecting significant differences would be harder given the proximity and raised awareness of CVD risk factors among these relatives. Thus, our comparison results could be considered conservative and we would expect larger differences if our FH population were to be compared with the general Spanish population.

Conclusions

Adult patients with FH report better lifestyles, mainly a healthier diet in general and a greater adherence to the MD in particular, than their non-FH relatives. As one would hope, patients with FH and a history of CVD report a lower consumption of total fat and SFA, follow dietary recommendations best, and are the least likely to smoke.

Specifically, FH patients stand out for their high consumption of vegetables, olive oil, fish and skimmed milk products, and their low consumption of pastries, sugary sodas and red meats. This dietary pattern translates into a lower consumption of saturated fats and cholesterol. Yet, this patient group’s consumption of saturated fats and sugars still exceeds general recommendations, which shows room for improvement and an opportunity for targeted intervention in future longitudinal studies in our cohort. Despite the high cardiovascular risk associated with FH and the availability of lipid-lowering therapy, a healthy diet and a better distribution of fat intake could be important allies in controlling CVD-related risk factors.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Teresa Pariente for her hard work in managing the familial cascade screening from the beginning of the SAFEHEART study; all the Spanish Familial Hypercholesterolemia Foundation team for assistance in the recruitment and follow-up of participants; and the FH families for their valuable contribution and willingness to participate. Financial support: This work was supported by Fundación Hipercolesterolemia Familiar; the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII; grant numbers G03/181 and FIS PI12/01289); and Centro Nacional de Investigación Cardiovascular (CNIC; grant number 08-2008). None of the funding sources played any role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: R.A.-O. and P.M. designed and conducted the research. R.A.-O., P.M., R.A. and N.M. participated in database design and data input. R.A.-O., P.M. and G.Q.-N. analysed the data. R.A.-O., P.M., R.A., N.M., F.F.-J., O.M.-G., J.L.D.-D., D.Z., F.A. and J.A.G.-S. participated in recruitment of patients. R.A.-O., P.M. and J.R.B. wrote the paper. R.A.-O. and P.M. had primary responsibility for final content. P.M. conceived, design and supervised the SAFEHEART study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki on ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects and was approved by the local ethic committee (number 01/09) of the University Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz (Madrid), acting as the sole committee for the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study. All data and blood samples were obtained prior to informed consent. Samples were anonymized for further analysis. If the patient was not willing to take part in the study, this did not cause any prejudice as to future treatment or care.