Spain has the highest percentage of healthcare workers (HCW) infected with SARS-CoV-2 (WHO, 2019). This has led to significant concern among HCW precipitating emotional responses of anxiety, depression, and acute stress. We aimed to (1) explore differential presence of these symptoms among HCW compared with non-HCW; (2) compare their presence in the different health system roles; and (3) study the relationship between the emotional state of HCW and environmental variables.

Participants conducted a national self-reported online questionnaire starting on 29 March to 5 April 2020, which covers the peak of the infection (WHO, 2019), the questionnaire was distributed by social networks, applying an exponential non-discriminative snowball sampling (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Luo, Haase, Guo, Wang, Liu and Yang2020; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Tripathy, Kar, Sharma, Verma and Kaushal2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, Ho and Ho2020).

HCW were eligible if: (a) they worked in a hospital or outpatient clinic, (b) had been occupationally active since the debut of the first case in Spain and (c) were aged between 18 and 65. We categorized the final 781 participants into: 385 physicians (169 trainees and 215 seniors), 233 nurses, and 164 other professionals. Participants (1006) were allocated in the non-HCW if: (a) had been occupationally active since the debut of the first case in Spain and (b) were between 18 and 65 years old. The presence of a current or past mental disorder reported was considered exclusion criteria in both samples. Informed consent was provided. The study was approved by the ethics committee.

Sociodemographic information, as well as whether responders presented symptoms compatible with COVID-19 (suspected cases) or had undergone PCR with a positive result (confirmed cases) was required. Moreover, perception of the quality of the information received (insufficient/adequate/excessive) as well as effectiveness of the protection measures provided (insufficient/adequate/excessive) were included. The questionnaire included three scales to assess anxiety, depression, and acute stress: Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HARS) (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1959), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Bech, Reference Bech1988), and the Acute Stress Disorder Inventory (ASDI): consisting of a list of symptoms based on the clinical criteria of Acute Stress Disorder in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013).

Anxiety, depression, and acute stress in the study groups

Regarding anxiety symptoms (F(1, 1783) = 0.93, p = 0.34), the HCW group (M 18.2, s.d. 10.4) did not show significant higher symptoms of anxiety than non-HCW (M 16.9, s.d. 10.3). In depression, results showed no differences in BDI scores (F(1, 1780) = 0.16, p = 0.68) in HCW (M 4.0, s.d. 3.8) compared to non-HCW (M 3.6, s.d. 3.9). However, when clinical cut-off score of 4 (absent or minimal depression v. mild/moderate/severe depression) are applied to BDI responses, a trend toward greater depressive symptoms in HCW is observed (χ2 = 2.9, p = 0.09).

Finally, HCW showed higher symptoms of acute stress (F(1, 1745) = 8.1, p = 0.004) with higher ASDI scores (M 4.9, s.d. 3.1) than non-HCW (M 4.3, s.d. 3.1).

Comparisons according to the role within the healthcare system

Nurses scored higher in all emotional assessments [anxiety: 21.3 (10.9) v. 16.6 (9.6) v. 17.3 (10.4), p < 0.001; depression 4.5 (4.2) v. 3.2 (3.1) v. 3.4 (3.4), p < 0.03; acute stress 5.5(3.2) v. 4.8 (3.0) v. 4.4 (3.3), p < 0.009] than physicians and other professionals, respectively. No significant differences were found between physicians and other health professionals in all three clinical symptoms.

According to the degree of expertise within physicians, when clinical cut-offs score of 4 are applied to BDI, significant differences were found with up to 40.8% of trainees fulfilling scores for depression compared to 30.7% of specialists (p = 0.04). No differences in acute stress symptoms or anxiety were found between levels of expertise.

Relation between emotional state and COVID-19, level of information, and level of protection

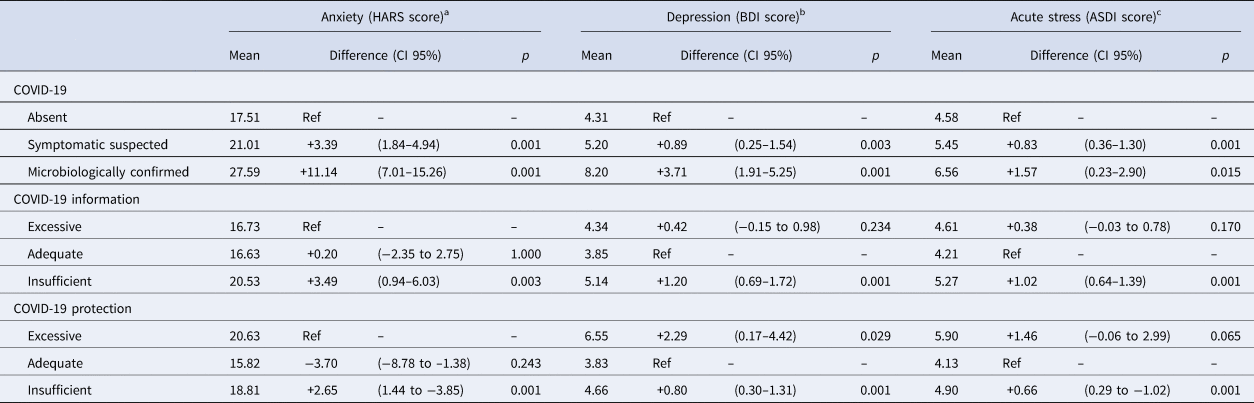

Mean and CI 95% are presented in Table 1. A confirmatory diagnosis of the disease increased the average HARS score (p < 0.001), BDI score (p = 0.001), and ASDI score (p = 0.015), compared with the presence of suspected disease. This latter increased the HARS (p = 0.001), BDI (p = 0.003), and ASDI (p = 0.001) means compared to healthy HCW. Regarding the information received, those participants considering they were provided insufficient information showed higher HARS (p = 0.003), BDI (p = 0.001), and ASDI (p = 0.001) scores than those respondents who consider it adequate. No differences were found between adequate and excessive information in any of the measures. According to the protection measures, participants who considered the protection insufficient showed an increased average of HARS (p = 0.001), BDI (p = 0.001), and ASDI (p = 0.001) scores than those who consider it adequate. Finally, the excesses of protection perceived increased BDI scores (p = 0.029) than those who considered it adequate. No differences on HARS or ASDI scores between adequate and excessive protection were found.

Table 1. Relation between anxiety, depression, and acute stress symptoms and COVID-19, level of information and level of protection

a Ref, Reference category for comparison within variable. General linear model R 2 (p value) for COVID-19, COVID-19 information, and COVID-19 protection were 0.063 (<0.001), 0.077 (<0.001), and 0.050 (<0.001), respectively, adjusted by age and gender.

b Ref, Reference category for comparison within variable. General linear model R 2 (p value) for COVID-19, COVID-19 protection, and COVID-19 information were 0.046 (<0.001), 0.042 (<0.001), and 0.036 (<0.001), respectively, adjusted by age and gender.

c Ref, Reference category for comparison within variable. General linear model R 2 (p value) for COVID-19, COVID-19 protection, and COVID-19 information were 0.044 (<0.001), 0.040 (<0.001), and 0.048 (<0.001), respectively, adjusted by age and gender.

Subsequent analyses of variance are corrected for age and gender.

Findings suggest that COVID-19 has greater impact on the mental health of HCW than in non-HCW. Nurses and physician trainees are the most vulnerable groups. Adequate information and availability of protective measures are associated with emotional wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants, especially frontline clinicians who have kindly responded to the survey.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

Dr R. Rodriguez-Jimenez has been a consultant for, spoken in activities of, or received grants from: Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Madrid Regional Government (S2010/ BMD-2422 AGES; S2017/BMD-3740), JanssenCilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Ferrer, Juste, Takeda, Exeltis, Angelini, and Casen-Recordati. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.