Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continues to circulate, with corresponding increases in the number of individuals living with long COVID – a general term for post-acute sequelae of SARS CoV-2 infection (PASC) or post-COVID-19 conditions (PCC) at least three months after SARS-CoV-2 infection onset, lasting at least two months (Soriano, Murthy, Marshall, Relan, & Diaz, Reference Soriano, Murthy, Marshall, Relan and Diaz2022). Prevalence estimates of long COVID vary (2–43%) (Bygdell et al., Reference Bygdell, Leach, Lundberg, Gyll, Martikainen, Santosa and Nyberg2023; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Haupert, Zimmermann, Shi, Fritsche and Mukherjee2022), with some studies estimating that at least 69 million people have had long COVID (Ballering, van Zon, olde Hartman, & Rosmalen, Reference Ballering, van Zon, olde Hartman and Rosmalen2022; Davis, McCorkell, Vogel, & Topol, Reference Davis, McCorkell, Vogel and Topol2023). Nonetheless, we have poor understanding of risk factors for and underlying mechanisms of long COVID, symptoms are often non-specific, and we lack objective diagnostic tests (Choutka, Jansari, Hornig, & Iwasaki, Reference Choutka, Jansari, Hornig and Iwasaki2022). Varied clinical manifestations include prolonged fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction (Soriano et al., Reference Soriano, Murthy, Marshall, Relan and Diaz2022), and new onset pulmonary, cardiovascular, muscle, or neurological conditions (Bull-Otterson, Reference Bull-Otterson2022; Thaweethai et al., Reference Thaweethai, Jolley, Karlson, Levitan, Levy and McComsey2023). To enable better documentation of this broad and heterogeneous condition, an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code U09.9 was released October 2021 (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Mehta, Sharma, Mane, Singh and Xie2023). Long COVID poses a significant threat to population health (Ballouz et al., Reference Ballouz, Menges, Anagnostopoulos, Domenghino, Aschmann, Frei and Puhan2023; O'Mahoney et al., Reference O'Mahoney, Routen, Gillies, Ekezie, Welford, Zhang and Khunti2023), and it is necessary to identify risk factors to inform targeted screening, early detection, and disease management.

Several long COVID risk factors have been identified, including female sex, older age, pre-existing asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), high body mass index (BMI), and higher acute disease severity (Vincent, Ofovwe, Gschwandtner, Shergill, & Faruqui, Reference Vincent, Ofovwe, Gschwandtner, Shergill and Faruqui2022; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Zhao, Yan, Li, Lu, Liu and Lu2022). However, few studies have examined if pre-existing psychiatric conditions increase long COVID risk. Although the pathophysiology of long COVID is not known (Castanares-Zapatero et al., Reference Castanares-Zapatero, Chalon, Kohn, Dauvrin, Detollenaere, Maertens de Noordhout and Van den Heede2022), psychiatric disorders are associated with physiological, behavioral, and psychosocial factors (Bradford et al., Reference Bradford, Kim, Braxton, Marx, Butterfield and Elbogen2008; Sally Rogers, Anthony, & Lyass, Reference Sally Rogers, Anthony and Lyass2004; Vancampfort et al., Reference Vancampfort, Stubbs, Mitchell, De Hert, Wampers, Ward and Correll2015; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wang, Ye, Zou, Chen, Wang and Zou2023b) that could increase risk for persistent adverse outcomes of infectious diseases like COVID-19. Moreover, studies have linked psychiatric diagnoses with increased risk for COVID-19 infection (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ni, Yan, Lu, Zhao, Xu and Lu2021; Nishimi, Neylan, Bertenthal, Seal, & O'Donovan, Reference Nishimi, Neylan, Bertenthal, Seal and O'Donovan2022b), and more severe sequelae once infected (Nishimi et al., Reference Nishimi, Neylan, Bertenthal, Dolsen, Seal and O'Donovan2022a; Vai et al., Reference Vai, Mazza, Colli, Foiselle, Allen, Benedetti and Picker2021), compared to those without such conditions. Diagnosing long COVID in patients with psychiatric disorders may be challenging in some cases due to overlapping symptoms such as fatigue, neurocognitive impairment, and sleep disturbance, and due to comorbidities with overlapping symptoms such as autoimmune and cardiovascular disorders (Krantz, Shank, & Goodie, Reference Krantz, Shank and Goodie2022; Momen et al., Reference Momen, Plana-Ripoll, Agerbo, Benros, Børglum, Christensen and McGrath2020; O'Donovan et al., Reference O'Donovan, Cohen, Seal, Bertenthal, Margaretten, Nishimi and Neylan2015).

Emerging evidence has indicated increased risk for long COVID in individuals with psychiatric disorders. A meta-analysis of 634 734 patients examining various risk factors indicated that pre-existing depression and/or anxiety increased long COVID risk by 19% (Tsampasian et al., Reference Tsampasian, Elghazaly, Chattopadhyay, Debski, Naing, Garg and Vassiliou2023). However, in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health records study through December 2021, pre-existing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia were not associated with ‘long COVID care’ (Ioannou et al., Reference Ioannou, Baraff, Fox, Shahoumian, Hickok, O'Hare and Hynes2022). In contrast, a case–control study of VA patients in May 2021 identified that anxiety, depression, and substance abuse were significant risk factors for long COVID (defined as health sequelae in excess of non-infected controls) (Xie, Bowe, & Al-Aly, Reference Xie, Bowe and Al-Aly2021). Importantly, no prior large-scale studies was designed to focus specifically on psychiatric disorders, which may have led to poor consideration of potential confounders and divergence in results across studies. Moreover, no prior studies have included a broad range of common psychiatric disorders or compared results across disorders, or examined if results differed by age groups.

In the current study, we focused specifically on psychiatric disorders, examining associations between pre-existing psychiatric disorders and long COVID diagnosis among 660 217 VA patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. We hypothesized that individuals with psychiatric disorders would have increased risk of long COVID diagnoses, considering any and specific psychiatric disorders. As long COVID risk may be patterned by age, with mixed evidence of older or middle age increasing risk (Subramanian et al., Reference Subramanian, Nirantharakumar, Hughes, Myles, Williams, Gokhale and Haroon2022; Vincent et al., Reference Vincent, Ofovwe, Gschwandtner, Shergill and Faruqui2022; Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Zhao, Yan, Li, Lu, Liu and Lu2022), and psychiatric disorder diagnoses tend to be more prevalent among younger v. older veterans (Frueh et al., Reference Frueh, Grubaugh, Acierno, Elhai, Cain and Magruder2007; Seal, Bertenthal, Miner, Sen, & Marmar, Reference Seal, Bertenthal, Miner, Sen and Marmar2007), we performed secondary analyses stratified by age.

Methods

Study participants

This retrospective cohort study included 660 217 individuals who accessed VA healthcare nationwide between 20 February 2020, and 6 February 2023. We restricted to individuals with at least one positive SARS-CoV-2 test recorded in VA clinical notes to assess long COVID in an at-risk population. From 2 288 650 patients who accessed VA healthcare during the study period, 733 455 had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, 710 860 had at least one VA encounter in the 12 months prior to infection (indicating active healthcare use), 666 449 had a COVID-19 index infection date with at least 90 days of follow-up post-infection (i.e. infected at least 90 days before the end of follow-up; ensuring adequate time to develop long COVID), and 660 217 had complete covariate data. Individuals could have multiple positive SARS-CoV-2 infections; one's first infection reported in VA records was defined as their index infection date. All data came from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, a database of VA patient administrative and electronic health records (EHR) from inpatient and outpatient facilities, and the VA COVID-19 Shared Data Resource (VA HSR RES 13-457), a database of VA patients with SARS-CoV-2 tests recorded in VA clinical notes. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Research, University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco VA Health Care System Human Research Protection Program, and waiver of informed consent was approved for EHR analyses. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Measures

Outcome

Long COVID diagnosis was defined as at least two encounters with ICD-10-CM diagnostic code U09.9, ‘Post COVID-19 condition, unspecified’ at any inpatient or outpatient clinical encounter. This operationalization conservatively created a more specific (i.e. fewer false positives) long COVID case measure, and potentially indicated more severe or persistent long COVID sequelae v. a single encounter code.

Primary predictors

Psychiatric disorders included diagnoses of depressive, posttraumatic stress, anxiety, adjustment, alcohol use, substance use, bipolar, psychotic, attention-deficit/hyperactivity (ADHD), dissociative, and eating disorders, identified with ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM codes from inpatient or outpatient clinical data in five years preceding the index infection date (Nishimi et al., Reference Nishimi, Neylan, Bertenthal, Seal and O'Donovan2022b). For each individual disorder type, diagnosis was defined as disorder codes from at least two separate encounters (e.g. code F43 for PTSD at two separate encounters), to improve precision and limit misclassification from provisional diagnostic codes (Seal et al., Reference Seal, Bertenthal, Miner, Sen and Marmar2007). We also considered diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder, defined as codes of any psychiatric disorders included from at least two separate encounters (e.g. code F43.1 for PTSD at one encounter and code F33.1 for major depressive disorder (MDD) at another encounter).

Covariates

Socio-demographic covariates included age, sex, and an indicator of combined race and ethnicity. As COVID-19 vaccination may reduce long COVID risk (Al-Aly, Bowe, & Xie, Reference Al-Aly, Bowe and Xie2022), we adjusted for vaccination status as of one's index infection date: unvaccinated (no vaccine shots or less than fully vaccinated), fully vaccinated (completed the full original primary series of two mRNA or one viral vector vaccine), or fully vaccinated and boosted (at least one additional vaccine shot at least 60 days after the primary series). Models also included a random effect of calendar time (quarter of the year starting in Spring 2020 through Spring 2023) at index diagnosis to account for temporal changes in both risk for long COVID across COVID-19 variants (Davis et al., Reference Davis, McCorkell, Vogel and Topol2023) and diagnosis with U09.9 codes over time (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Scott, Surinach, Chambers, Benigno and Malhotra2022). Medical comorbidities included obesity (BMI ⩾ 35 closest in time to index infection date) and medical diagnoses in the two years prior to the index infection (see Table 1). Smoking status (current or former smoker, never smoker) was included as behavioral risk factor. All covariates were derived from administrative data or ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM codes in EHRs.

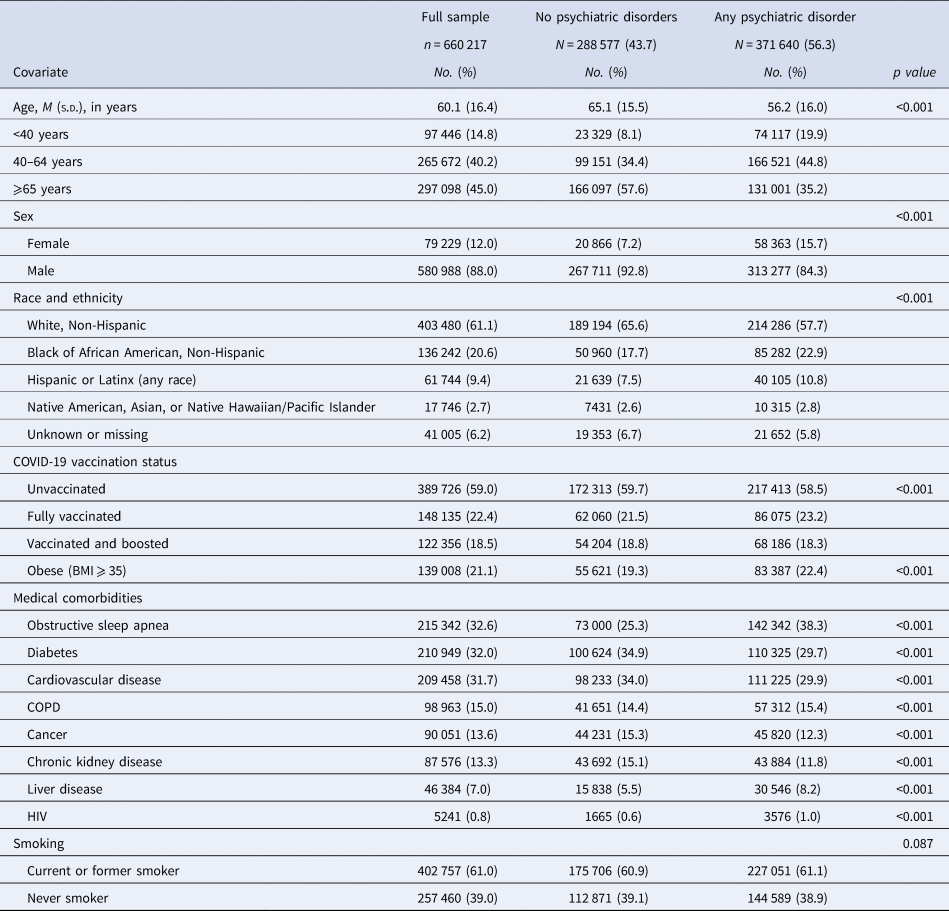

Table 1. Distribution of covariates among 660 217 VA patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 tests

COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; VA, U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs.

Analyses

We first examined the distribution of covariates in the sample and by psychiatric disorder. Primary analyses were generalized linear models with Poisson distribution and log link for relative risks (RR) with robust error variance (Zou, Reference Zou2004) for associations between psychiatric diagnoses and long COVID diagnosis. Model 1 adjusted for potential confounders including socio-demographic factors (age [both age and age squared, which best fit the data], sex, race and ethnicity) and time (random effect of calendar quarter). Model 2 additionally adjusted for vaccination status, medical comorbidities, and smoking, which may be confounders or mediators. We examined models for any psychiatric disorder v. none and for each specific individual disorder v. none. To limit imprecise estimates, specific disorder models were only conducted when sample prevalence was ⩾3% (excluding ADHD 2.6%, dissociative disorder 0.4%, and eating disorders 0.4%). To identify whether associations differed by age (Ioannou et al., Reference Ioannou, Baraff, Fox, Shahoumian, Hickok, O'Hare and Hynes2022), secondary analyses included age-stratified models (18-39, 40–64, ⩾65). In sensitivity analyses, we reran models using a more lenient outcome definition, requiring one or more codes of U09.9 at any patient encounter. Lastly, increased healthcare interaction may be associated with higher likelihood of long COVID diagnoses. In additional sensitivity analyses, models adjusted for level of primary care interaction in the year before index infection (0–1, 2–3, 4–6, 7 + primary care visits). Data were prepared with SAS 9.4, analyzed with Stata 17.0, and statistical significance was set a priori at p < 0.05 using two-sided hypothesis tests.

Results

The sample of 660 217 VA patients was 60.1 (s.d. = 16.4) years old on average and 88.0% male (Table 1). Over half (56.3%) the sample had at least one psychiatric disorder diagnosis, which was associated with younger age, female sex, Black or African American race, Hispanic or Latinx ethnicity, vaccination status, and medical comorbidities. The raw prevalence of some medical comorbidities by psychiatric diagnosis was likely confounded by age and therefore departs from prior findings in some cases (e.g. older patients were less likely to have psychiatric diagnoses, but more likely to have cardiovascular disease) (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Mikkelsen, Luitva, Song, Kasela, Aspelund and Valdimarsdóttir2023). By February 2023, 9405 (1.4%) individuals received at least two U09.9 diagnostic codes. As in prior studies (Ioannou et al., Reference Ioannou, Baraff, Fox, Shahoumian, Hickok, O'Hare and Hynes2022), the prevalence of long COVID diagnosis was higher among women (1.8%) v. men (1.4%), and Hispanic or Latinx (3.7%) individuals v. all other racial/ethnic groups (1.0–1.6%). In addition, the prevalence of long COVID diagnosis was higher among middle-aged (40–64 years, 1.8%) and lower among older (older than 65 years, 1.1%) individuals compared to younger adults (18–39 years, 1.5%; RRs = 1.20, 95% CI 1.13–1.27, and 0.73, 95% CI 0.69–0.78, respectively).

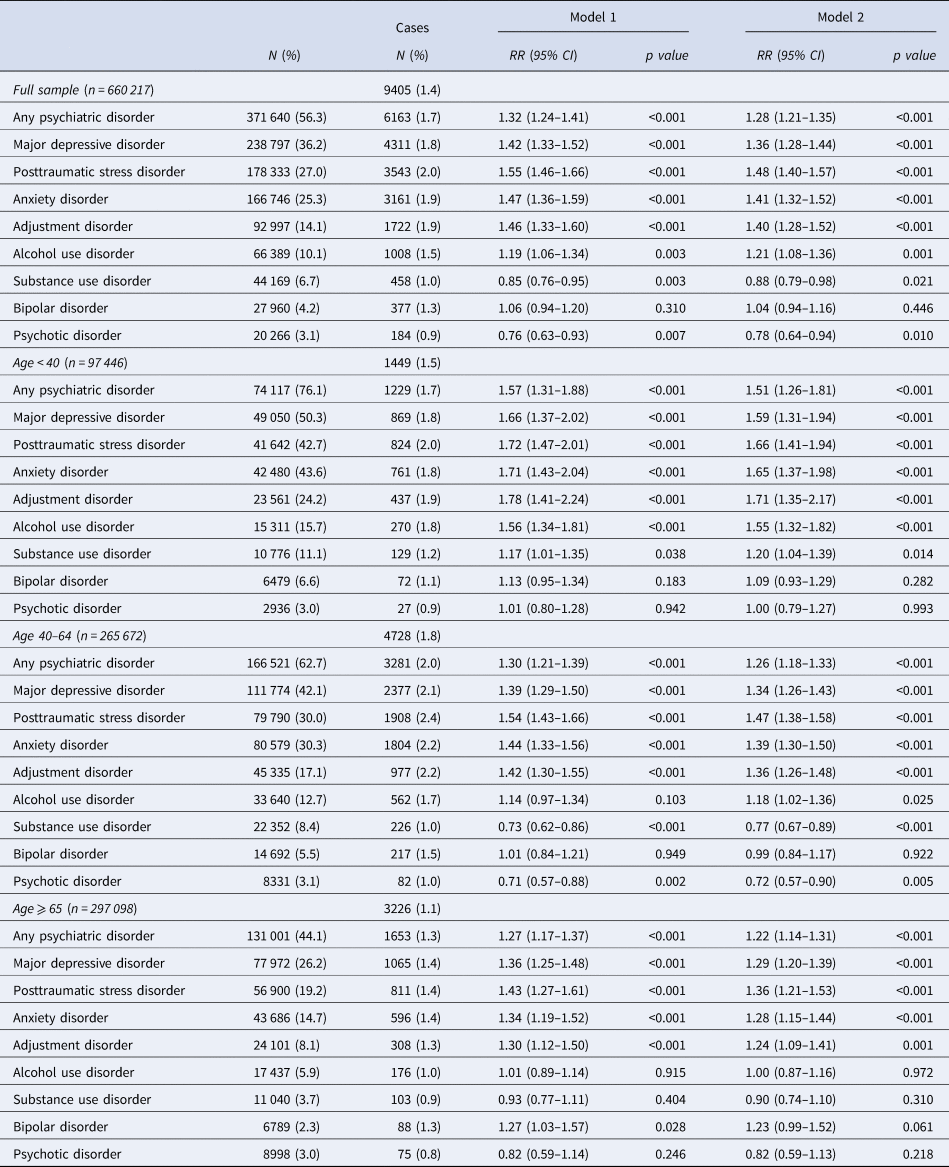

Relative to patients with no psychiatric disorders, those with any psychiatric disorder diagnosis had 32% higher risk for a long COVID diagnosis (RR = 1.32, 95% CI 1.24–1.41), adjusting for confounders (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Adjusting for vaccination status, obesity, medical comorbidities, and smoking only slightly attenuated the association (RR = 1.28, 95% CI 1.21–1.35). Most individual psychiatric disorders were associated with elevated risk for long COVID diagnosis, including MDD, PTSD, anxiety, adjustment, and alcohol use disorders. However, bipolar disorder was unassociated with long COVID diagnosis, while substance use and psychotic disorders were associated with lower risk for receiving long COVID diagnoses.

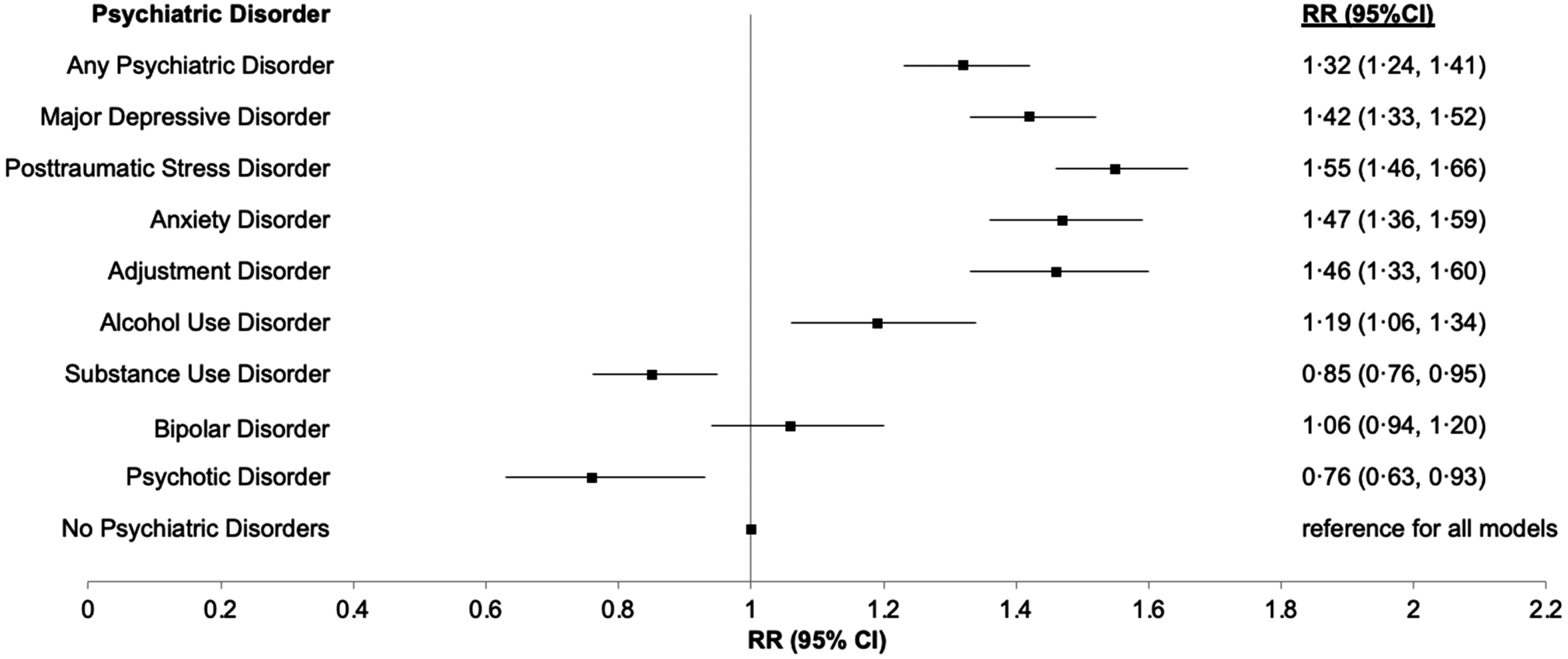

Table 2. Associations between psychiatric disorders and long COVID diagnosis among VA patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 tests, in the full sample and age-stratified

CI, confidence intervals; RR, relative risk; VA, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference group for each model is No Psychiatric Disorders. Outcomes are long COVID diagnosis (U09.9 clinical code at 2 or more encounters).

Model 1: age, age squared, sex, race/ethnicity, and time.

Model 2: Model 1 plus vaccination status, medical comorbidities, and smoking.

Figure 1. Relative risks of long COVID for individual psychiatric disorders among the full sample, confounder adjusted.

Note. RR, relative risk; CI, confidence intervals; reference group for each model is No psychiatric disorders; each individual psychiatric disorder was estimated in a separate model as the primary predictor and adjusted for age, age squared, sex, race/ethnicity, and calendar time of index infection.

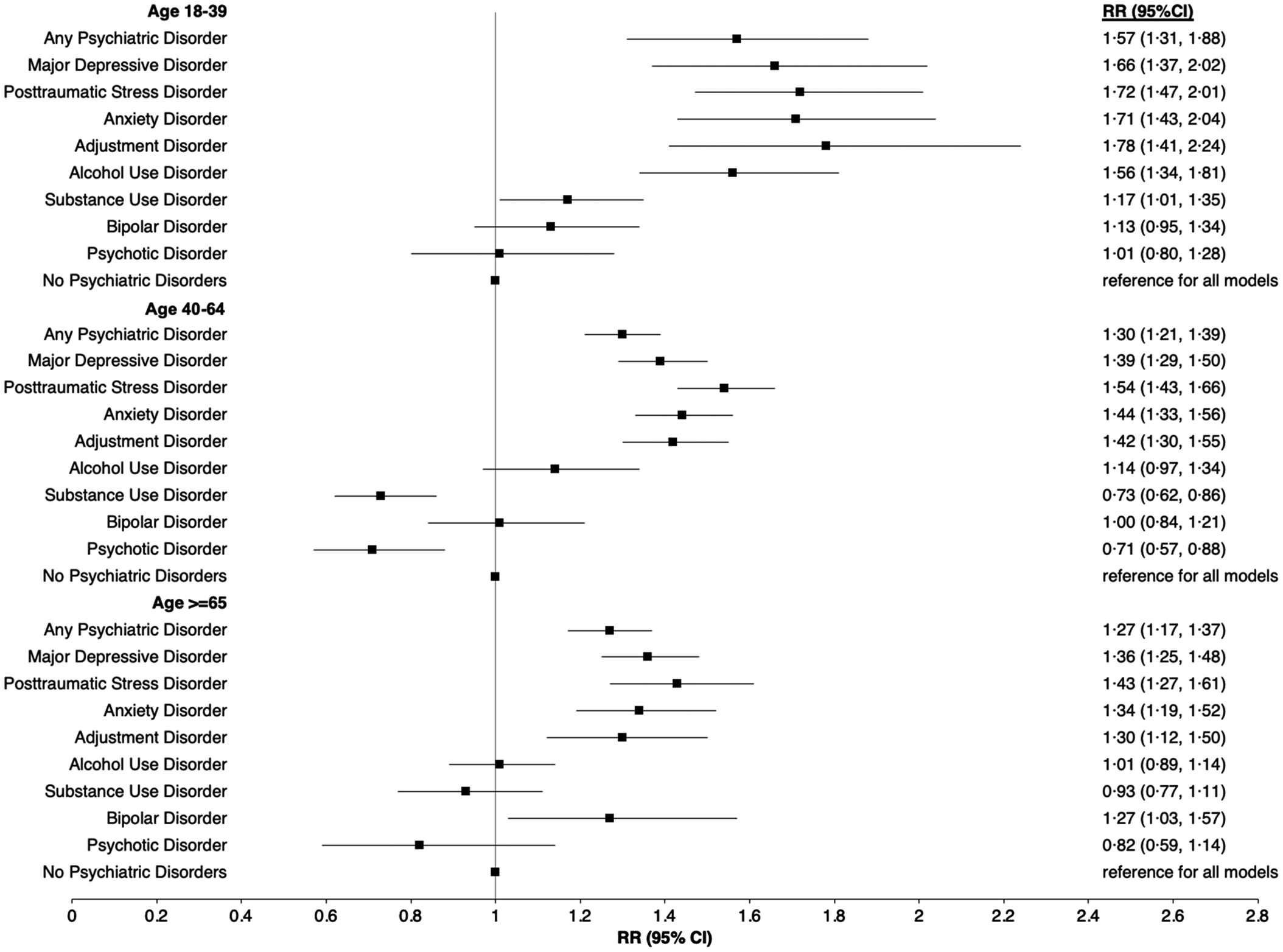

In age-stratified models, associations between any psychiatric disorder and several individual disorders (MDD, PTSD, anxiety, adjustment, and alcohol use disorder) with long COVID diagnosis were strongest among younger (age 18–39) patients (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Association for substance use and psychotic disorders varied by age, with both disorders associated with decreased risk of long COVID diagnosis among patients aged 40–64, but unassociated or associated with increased risk in both younger (age 18–39) and older (age ⩾ 65) patients. Associations with bipolar disorder were also patterned by age; bipolar disorder was unassociated with long COVID diagnosis in younger (age < 65) patients, but associated with increased risk in older (age ⩾ 65) patients.

Figure 2. Relative risks of long COVID for individual psychiatric disorders stratified by age, confounder adjusted.

Note. RR = relative risk; CI = confidence intervals; reference group for each model is No psychiatric disorders; each individual psychiatric disorder was estimated in a separate model as the primary predictor and adjusted for age, age squared, sex, race/ethnicity, and calendar time of index infection.

In sensitivity analyses using one or more U09.9 codes, a larger proportion of individuals were classified as having long COVID diagnosis (n = 22 250, 3.4%). Associations were in similar directions but smaller in magnitude compared to primary models (online Supplemental Table S1). When adjusting for level of primary care interaction prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection, estimates were attenuated slightly but most primary findings remained the same (online Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

Among 660 217 VA patients in this retrospective cohort study, diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder was associated with 32% increased risk for long COVID diagnosis. This association was robust to adjustment for socio-demographics, vaccination, medical conditions, and behavioral factors, and was strongest among younger adults (age 18–39). While individuals with psychiatric disorders appeared to be at increased risk for long COVID diagnoses overall, associations were strongest among younger adults and those with depressive, anxiety, and stress-related conditions. In contrast, individuals with substance use, bipolar, and psychotic disorders had similar or lower risk for long COVID diagnoses than those with no pre-existing psychiatric disorders.

Consistent with our hypotheses, having any pre-existing psychiatric disorder was associated with elevated risk for long COVID diagnosis. Our findings align with a recent meta-analysis that linked depression and/or anxiety with higher risk for long COVID (Tsampasian et al., Reference Tsampasian, Elghazaly, Chattopadhyay, Debski, Naing, Garg and Vassiliou2023), and with other studies associating any psychiatric disorder with increases in U09.9 codes (Hedberg et al., Reference Hedberg, Granath, Bruchfeld, Askling, Sjöholm, Fored and Naucler2023; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Williams, Walker, Mitchell, Niedzwiedz, Yang and Steves2022). No prior studies examined whether associations of psychiatric disorders with risk for long COVID differed by age. We found differences in age-stratified analyses, with associations between psychiatric disorders and long COVID diagnosis tending to be strongest among younger (age 18–39) relative to older individuals. Pre-existing psychiatric conditions may be more robustly associated with risk for diagnoses of long COVID among younger adults who are at generally lower risk for physical health problems and comorbid conditions that could mask long COVID. Our current analyses extend the evidence base by focusing on psychiatric disorders explicitly (e.g. including multiple different diagnoses and examining individual disorder effects), including a sample with high psychiatric burden, and focusing on a population at high risk for long COVID by nature of age and comorbidity.

Several individual psychiatric disorders were associated with long COVID diagnosis risk in our study, including MDD, PTSD, anxiety, adjustment, and alcohol use disorder. These disorders share several symptoms related to somatization (sleep disturbance or fatigue) and cognitive impairment, which are also common long COVID symptoms. Among individuals with pre-existing psychiatric disorders, these symptoms could have developed or worsened following COVID-19 illness. Therefore, individuals with psychiatric conditions may have been misdiagnosed as having long COVID based on psychiatric symptoms alone. However, it is also possible that individuals with pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses are less likely to receive long COVID diagnoses because symptoms are attributed to their pre-existing disorders and not to long COVID. Our findings are generally consistent with prior studies assessing ‘any psychiatric disorder’ and some specific disorders, and including a study of PTSD and adjustment disorders with risk for long COVID (Kostev, Smith, Koyanagi, & Jacob, Reference Kostev, Smith, Koyanagi and Jacob2022), but are inconsistent with another VA study (Ioannou et al., Reference Ioannou, Baraff, Fox, Shahoumian, Hickok, O'Hare and Hynes2022). Contradicting findings may be due to different ‘long COVID’ definitions (our definition of multiple U09.9 encounters v. any of four codes related to COVID-19 three months after infection) or study time period (our study included follow-up through February 2023 v. December 2021).

Notably, diagnoses of substance use or psychotic disorders were associated with lower risk for receiving a long COVID diagnosis in our study, consistent with one other case–control study (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Mehta, Sharma, Mane, Singh and Xie2023), and bipolar disorder was unassociated with long COVID risk. These findings are surprising, given prior work indicating that substance use, bipolar, and psychotic disorders are linked with more severe COVID-19 outcomes (Nishimi et al., Reference Nishimi, Neylan, Bertenthal, Dolsen, Seal and O'Donovan2022a; Vai et al., Reference Vai, Mazza, Colli, Foiselle, Allen, Benedetti and Picker2021). One possibility is that some drugs prescribed for psychotic disorders (e.g. second-generation antipsychotics) could be protective against severe COVID-19 outcomes (Poletti et al., Reference Poletti, Vai, Mazza, Zanardi, Lorenzi, Calesella and Benedetti2021). Another possibility is that individuals with substance use, bipolar, or psychotic disorders are less engaged in primary care relative to other disorders, thus fail to have long COVID diagnosed. However, when adjusting for primary care utilization, our associations for these conditions were largely unaffected. Clinicians may also exhibit biases in diagnostic practices, such that they are less likely to attribute non-specific symptoms to long COVID among individuals with substance use, bipolar, or psychotic disorders. Additionally, individuals with these disorders may be unable to self-report long COVID symptoms (e.g. due to masking by complications of the disorder or drug use) or clinicians may mistake symptoms for side effects of medications or non-prescription drugs. Overall, accumulating data indicates that long COVID could be underdiagnosed among individuals with substance use, bipolar, and psychotic disorders. More research should examine potential risk for long COVID manifestations among individuals with these disorders, applying alterative study designs and measures beyond naturalistic clinical diagnoses in EHRs.

Several potential mechanisms may underly associations between psychiatric disorders and long COVID. Most psychiatric conditions are characterized by physiological dysregulations in stress-response systems, chronic low-grade inflammation, and alterations in immune markers (Gibney & Drexhage, Reference Gibney and Drexhage2013; Yuan, Chen, Xia, Dai, & Liu, Reference Yuan, Chen, Xia, Dai and Liu2019). While precise pathogenic mechanisms of long COVID are unclear, hypothesized processes include organ damage, persistent viral reservoirs, reactivation of latent virus, immune dysfunction or autoimmunity, clotting and endothelial abnormality, or microbiota dysbiosis (Altmann, Whettlock, Liu, Arachchillage, & Boyton, Reference Altmann, Whettlock, Liu, Arachchillage and Boyton2023; Davis et al., Reference Davis, McCorkell, Vogel and Topol2023). Several of these systems are altered in individuals with psychiatric conditions, which could predispose them to developing long COVID (Davis et al., Reference Davis, McCorkell, Vogel and Topol2023). Individuals with psychiatric disorders may also exhibit behavioral patterns that increase risk for poor COVID-19 sequelae and long COVID, including smoking, less healthy diet, and poor sleep quality, or have related risk factors such as obesity (Allison et al., Reference Allison, Newcomer, Dunn, Blumenthal, Fabricatore, Daumit and Alpert2009; Chwastiak, Rosenheck, & Kazis, Reference Chwastiak, Rosenheck and Kazis2011). While individuals with and without psychiatric conditions appear to accept vaccination at similar rates (Haderlein, Steers, & Dobalian, Reference Haderlein, Steers and Dobalian2022), and individuals with any psychiatric disorder diagnosis were slightly more likely to be vaccinated in the current study, psychiatric diagnoses may be associated with less robust immune response to vaccination (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Gillissie, Lui, Ceban, Teopiz, Gill and McIntyre2022), which could influence vaccination effectiveness and long COVID risk (Byambasuren, Stehlik, Clark, Alcorn, & Glasziou, Reference Byambasuren, Stehlik, Clark, Alcorn and Glasziou2023). Psychosocial factors, spanning healthcare access, social support, and living conditions, may also influence long COVID sequalae in individuals with psychiatric conditions (Bradford et al., Reference Bradford, Kim, Braxton, Marx, Butterfield and Elbogen2008; Sally Rogers et al., Reference Sally Rogers, Anthony and Lyass2004). Psychosocial factors may have complex impacts; for example, individuals with psychiatric disorders may interact more with the healthcare system and thus be more likely to have long COVID detected. In contrast, psychiatric symptoms and comorbidities overlap with long COVID symptoms, which may mask long COVID or make physicians less likely to attribute new onset symptoms to long COVID. Future work should examine biological mechanisms, and explore varied biological, behavioral, and psychosocial influences of long COVID risk.

There are several important limitations to the current study. First, there are inherent challenges in using EHRs for studying long COVID (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Honerlaw, Maripuri, Samayamuthu, Beaulieu-Jones, Baig and Brat2023a). There is ambiguity and heterogeneity in diagnostic codes, and we are likely underestimating long COVID cases by relying on U09.9 codes. However, adjustment for calendar time was used to account for differences in both prevalence and change in diagnostic code use over time. Moreover, patterns of long COVID diagnoses are important to consider even independent from the true occurrence of the disorder in the population. Second, diagnostic codes do not capture severity or constellation of long COVID symptoms. We defined the primary outcome as U09.9 codes at two or more encounters, to limit misclassification and potentially indicate more severe or chronic cases. Sensitivity analyses with one or more U09.9 codes indicated similar but weaker associations with psychiatric disorders. Third, the analytic sample included only VA patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 tests in VA clinical records, therefore we are likely excluding other at-risk patients who had COVID-19 that was not recorded at the VA. However, our inclusion restrictions helped to ensure our sample was at risk for long COVID and active in VA care, thus could feasibly have presented with long COVID in VA facilities. Fourth, all data was derived from VA health records, which are limited in terms of detailed demographic, socio-economic, or other confounder information, and includes diagnostic codes that may be imprecise or result in misclassification. Finally, generalizability beyond the sample may be limited, given the majority male sample of only VA patients.

We found that a diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder was associated with increased risk for long COVID diagnosis. Depressive, anxiety, and stress-related disorders were particularly robust risk factors for long COVID diagnosis, and associations were strongest among younger adults. In contrast, substance use and psychotic disorders were associated with lower risk for long COVID diagnoses and bipolar disorder was unassociated with risk, which could indicate missed long COVID diagnoses in individuals with some psychiatric disorders. In sum, understanding risk for long COVID among patients with psychiatric disorders requires consideration of age and specific psychiatric disorder type. Guidelines for diagnosing long COVID may need to be tailored for patients with psychiatric disorders.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724000114

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the efforts of all the contributors to the Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse and COVID-19 Shared Data Resource (HSR RES 13-457), enabling critical research on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in a timely and comprehensive manner. We are grateful to the Veterans for their service.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, the Medical Research Service of the SFVAHCS, and the Department of Veterans Affairs Sierra-Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC), the VA Office of Research and Development (KN; IK2CX 002627); the VA Sierra-Pacific MIRECC (DB); UCSF Department of Psychiatry Rapid Award, and UCSF Faculty Resource Fund Award (AOD). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors declare no competing interests.