Patients are becoming increasingly well informed about depression and its treatment, and often seek alternatives to traditional medical approaches. The herbal medicines industry has in recent years fallen under increasing scrutiny with regard to the safety of the many preparations on offer. Self-administration of St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) for mild-to-moderate depression is a pertinent example. Studies have shown that a significant number of people with a psychiatric disorder turn to complementary and alternative medicine (Reference Knaudt, Connor and WeislerKnaudt et al, 1999; Reference Unutzer, Klap and SturmUnutzer et al, 2000). In 2000 the Chief Medical Officer released an urgent communication to doctors about interactions between St John's wort and certain prescribed medications (Reference BreckenridgeBreckenridge, 2000) and in 2004 the European Community issued a directive on the use of traditional herbal medicinal products (European Community, 2004). In view of this we wanted to assess the appropriateness of treatments recommended by health shop staff for symptoms of mild-to-moderate depression.

Method

Members of staff from each of ten health shops offering herbal remedies within a 3-mile radius of Leeds city centre were included in the study. ‘ Health shop’ is defined as a shop dedicated to selling complementary and alternative medicines and not a shop offering holistic therapies such as massage, acupuncture, etc.

Information was gathered using participant observation (by J.E.R.; Reference SpradleySpradley, 1980). This ethnographic technique involves direct participation of the researcher (who may or may not reveal their reason for involvement) in the events being studied (Reference JonesJones, 1995; Reference SavageSavage, 2000). Members of staff were not aware that they were taking part. Health shop employees were presented with a customer (the researcher J.E.R.) complaining of a standard set of symptoms which commonly occur in mild-to-moderate depressive disorder (Box 1). Five of the shops (in the city centre) were visited by the researcher and the remaining five (within a 3-mile radius of the city centre) were telephoned by the researcher. In all ten interviews the same transcript was used (Box 1).

Health shop employees were then given an opportunity to ask questions to elicit further information about the condition presented. Additional symptoms described included: initial insomnia; weight loss; early morning wakening; not enjoying anything; weepiness; and sadness. The ‘customer’ had experienced symptoms for 2 months, had no recent life events, had not visited their general practitioner (GP) and was currently taking no over-the-counter preparations. Information given by health shop staff was recorded immediately after leaving the shop; only the names of the preparations suggested were recorded during the interview.

Box 1. Transcript of information given to health shop staff

-

• ‘I was wondering if you could give me some advice. I’ve not used herbal remedies before and was wondering if you could give me some information about things which may help me?’

-

• ‘I’ve not really been feeling myself lately. I’ve been a bit run down. I’m not sleeping as well as I used to and I’m just tired all the time. I can't be bothered doing anything, and I’m not concentrating very well. I’ve not really had much of an appetite either. Is there anything you could suggest?’

Results

Questions asked by shop staff

A range of questions were asked by health shop staff, varying from none (n=3) to questions concerning recent stress and life events (n=3) and currently prescribed medication (n=4). Only two employees asked if a GP had been consulted about the symptoms and three specifically asked if there was depression of mood. Additional questions were asked about recent illness, presence of anaemia, duration of the symptoms, age, worsening symptoms in winter and current appetite. One employee explained that she was not medically trained and that it would be wise to see the GP first in order to rule out common causes of fatigue and lack of concentration, such as anaemia. Another employee also mentioned the possibility of anaemia but did not suggest consulting a GP. Staff made no response when the ‘ customer’ explained that she was currently prescribed the oral contraceptive pill, despite evidence that St John's wort can decrease the efficacy of oral contraceptives (Reference Barnes, Anderson and PhillipsonBarnes et al, 2001).

Preparations suggested

A list of the preparations recommended and the information given about each is shown in Table 1. Information varied from none to advice about administration and beneficial effects.

Table 1. Preparations suggested by health shop staff and reference to the evidence base for their use in the treatment of depression

| Preparations | Information given about preparation by health shop staff | Evidence base summary |

|---|---|---|

| B-complex | No reason given for use | Evidence exists for its use in the treatment of depression |

| Slow-release capsules are better as they release the vitamins throughout the day as you need them | ||

| Bio-Strath liquid tonic | Liquid tonic | No evidence to support its use in depression |

| Take each day before meals for 2 weeks | ||

| Stimulates the appetite as well as helping with fatigue and convalescence | ||

| One bottle lasts for 1 month and you should feel the effects within 2 weeks | ||

| Research has been carried out in Sweden with women and children which was very successful | ||

| Builds up the immune system and aids recovery from illness | ||

| Bu Zhong Yi Qi Wan | Action similar to ginseng | No evidence to support its use in depression |

| Cats claw | Used for many things, general pick-up | No evidence to support its use in depression |

| Chinese herbal tea mix | Blend of 12 different herbs specially made to serve your needs | Ingredients were not divulged therefore reference to evidence base not possible |

| Coenzyme Q10 | Like a pint of lager, it goes to all the places in the body where it is needed | No evidence to support its use in depression |

| Floradix liquid tonic | Herbal tonic which is good for general energy boost and convalescence | No evidence to support its use in depression |

| Herbal tonic with natural iron supplement | No studies investigating effect | |

| Natural tonic with B-vitamin and iron content, good for stress and digestion | ||

| Gingko biloba | Good for increasing energy levels | No evidence to support its use in depression |

| Enhances the circulation and therefore increases energy levels | ||

| Ginseng | Boosts the circulation and therefore helps with low energy levels and poor concentration | Mixed evidence exists for its use in the treatment of depression |

| Liquid preparation is best | ||

| Siberian ginseng is the best formulation, especially for women | ||

| Guarana | Natural ‘caffeine’ boost | No evidence to support its use in depression |

| Multivitamins | Give a general boost to energy and vitality | No evidence to support its use in depression |

| Help you to absorb nutrients from food more effectively | No studies investigating effect | |

| Royal jelly | None | No evidence to support its use in depression |

| St John's wort | Very useful for depression | Evidence exists for its use in the treatment of depression |

| Must be careful to look for amount of active ingredient Hypericum perforatum as some preparations have more than others | ||

| Takes 7-10 days to take effect |

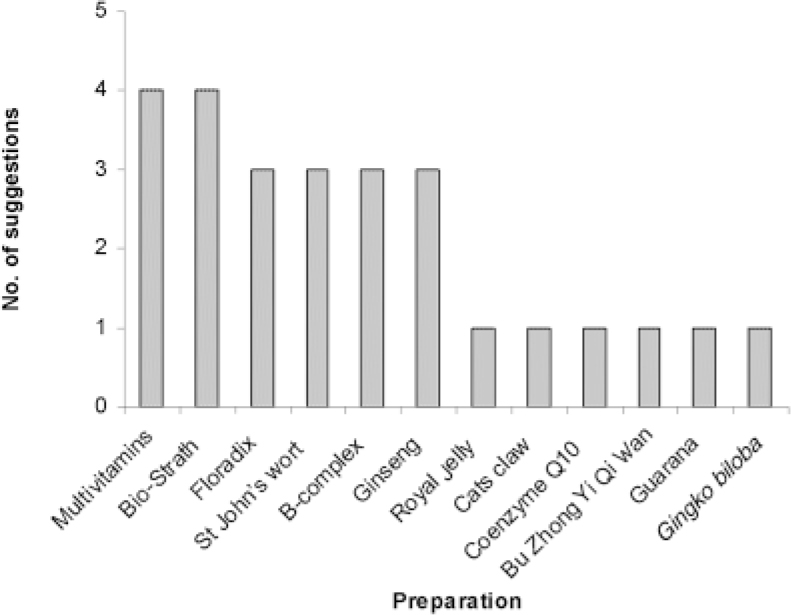

Twelve different preparations (not including Chinese tea) were suggested; the most popular were multi-vitamins (n=4) and Bio-Strath tonic (n=4) (Fig. 1). These were recommended for symptoms of tiredness and lack of concentration (Table 1). The employees who directly asked about depression of mood were also those who recommended St John's wort (n=3). The other seven recommended treatments for specific symptoms, for example, low energy, feeling run down, reduced appetite, and poor concentration. In conjunction with this, St John's wort was recommended purely for low mood rather than the biological symptoms of depression described in the interview.

Fig. 1 Preparations recommended by health shop staff

Two out of ten employees stated that the following remedies had no side-effects: ginseng; Gingko biloba; guarana; and B-complex. It was also suggested that these could be taken together with no harmful effects. Importantly, one employee also added that Chinese medicines, for example ginseng, have no interactions with other medications.

Other suggestions

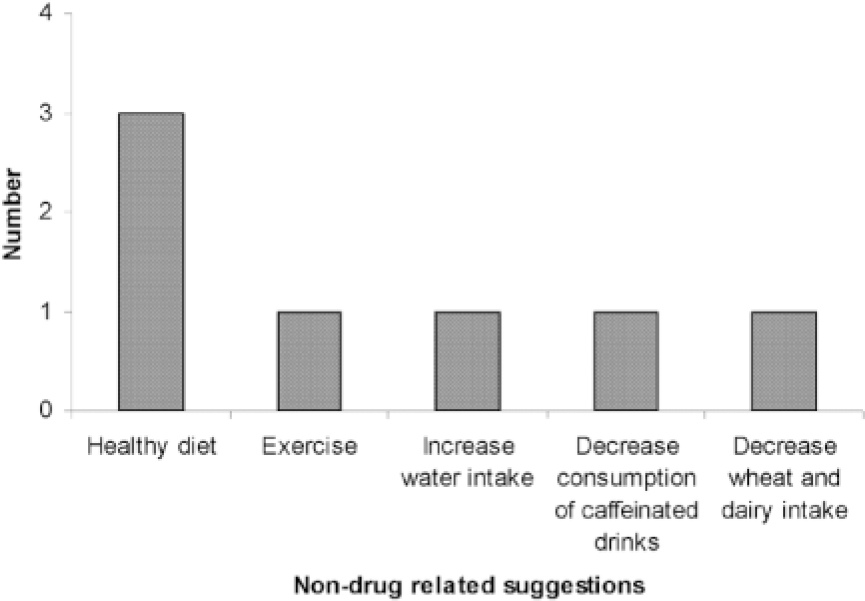

A number of suggestions for changes in diet and lifestyle were made (Fig. 2). Three employees stated that a healthy, balanced diet would be beneficial. It was suggested that increased exercise and fluid intake would increase energy and vitality, as would decreased consumption of caffeinated drinks, wheat and dairy produce. Two employees disclosed beneficial personal experience in the discussions.

Discussion

This study has shown that on approaching health shop staff with symptoms of mild-to-moderate depression, the general public are presented with a number of complementary and alternative medicines. Only 1 of the 13 preparations suggested, St John's wort, is supported by an evidence base (Linde et al, Reference Linde, Ramirez and Mulrow1996, Reference Linde, Mulrow and Berner2006). There is evidence for a putative role in the treatment of depression for a further two: ginseng (Panax ginseng) (Reference Wiklund, Mattsson and LindgrenWiklund et al, 1999) and B-complex vitamins (Reference Bell, Edman and MorrowBell et al, 1991). Furthermore, staff are unlikely to warn customers about potential interactions and adverse side-effects.

This study raises concerns about the virtually complete separation and independence of complementary and alternative medicine services from the National Health Service and pharmaceutical agencies. Many herbal remedies may have beneficial properties which could be used to great advantage if an adequate evidence base was developed. However, owing to the lack of overlap between the two sectors little is understood about each in either area. A more integrated approach would allow patients to benefit from herbal preparations, such as St John's wort, with optimum safety.

The majority of staff did ask additional questions prior to giving recommendations. This appeared to be in order to rule out a medically treatable physical condition (e.g. anaemia) or to decide upon appropriate preparations. Although the elements of a holistic and safe approach seem to be present, they were not consistently employed throughout all shops.

The choice of preparations offered appeared to be influenced by the amount of additional information elicited by staff. Results suggested that treatments were recommended according to individual symptoms rather than on the basis of a syndromal approach. The specific mood-lifting treatment, St John's wort, was only recommended when depression of mood was suspected. It appeared that the biological symptoms were not considered to be part of the same condition. However, patients rarely present with their own diagnosis; they more often complain of a collection of typical physical symptoms. It is also worrying that patients who have already been prescribed an antidepressant may seek additional help from herbal remedies (Reference Knaudt, Connor and WeislerKnaudt et al, 1999; Reference Unutzer, Klap and SturmUnutzer et al, 2000) when evidence suggests the possibility of interactions and increased side-effects (Reference Mills, Montori and WuMills et al, 2004), including serotonin syndrome (Reference Johne, Brockmoller and BauerJohne et al, 1999). It is important that both health shops and medical practitioners are aware of this and make this clear to patients.

Fig. 2 Diet and lifestyle modifications recommended by health shop staff

Potential influencing factors

The public nature of shops may lead employees to avoid asking personal questions, resulting in the suggestion of less-appropriate remedies for the treatment of depression. Many of the remedies were offered for a general ‘ boost’ or ‘pick-me-up’ (e.g. multivitamins), but with little evidence base. It is also worth noting that a large proportion of people may purchase the medicine without consulting shop staff.

More information specific to the interactions and side-effects of particular preparations may have been obtained from the product packaging if purchases had been made.

Although our research method precluded the collection of more detailed background information about the participants, participant observation enabled us to experience what members of the public are likely to encounter when searching for treatments for mild-to-moderate depression in health shops.

Conclusions

This study has identified a wide range of treatment options which are suggested by health shop staff when presented with common symptoms of depression. The majority of these, with the exception of St John's wort, have no firm evidence base, and have potentially serious drug interactions. There is a clear need for better communication between patient, medical practitioner and herbal agencies to ensure optimal patient choice, safety and therapeutic benefit in the treatment of depression. It may be possible to address some of these concerns during the training of doctors, allied health professionals and health shop staff.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.